A wrench in the works of COVID-19

Understanding the inner workings of the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may help us to disrupt it. Yin et al. focused on the viral polymerase essential for replicating viral RNA. They determined a structure of the polymerase bound to RNA and to the drug remdesivir. Remdesivir mimics an RNA nucleotide building block and is covalently linked to the replicating RNA, which blocks further synthesis of RNA. The structure provides a template for designing improved therapeutics against the viral polymerase.

Science, this issue p. 1499

Cryo-EM structures show how the drug remdesivir binds to the RNA polymerase to block RNA elongation.

Abstract

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has become a global crisis. Replication of SARS-CoV-2 requires the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) enzyme, a target of the antiviral drug remdesivir. Here we report the cryo–electron microscopy structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, both in the apo form at 2.8-angstrom resolution and in complex with a 50-base template-primer RNA and remdesivir at 2.5-angstrom resolution. The complex structure reveals that the partial double-stranded RNA template is inserted into the central channel of the RdRp, where remdesivir is covalently incorporated into the primer strand at the first replicated base pair, and terminates chain elongation. Our structures provide insights into the mechanism of viral RNA replication and a rational template for drug design to combat the viral infection.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that has arisen from widespread severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has become a humanitarian crisis, with more than 1.5 million infections and 87,000 deaths reported on 8 April 2020 (1, 2). These numbers have increased rapidly to more than 2.99 million infections and 207,000 deaths as of 27 April of 2020 (2). SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and several members of the betacoronavirus family, including bat and pangolin coronaviruses (3–5). Compared with the binding behavior of other coronaviruses, however, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a stronger binding affinity for the host receptor (6–10), which may explain why SARS-CoV-2 has a much higher incidence of human-to-human transmission, resulting in infections throughout the world.

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-strand RNA virus. Its replication is mediated by a multisubunit replication-and-transcription complex of viral nonstructural proteins (nsps) (11). The core component of this complex is the catalytic subunit (nsp12) of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (12, 13). By itself, nsp12 has little activity and its functions require accessory factors, including nsp7 and nsp8 (14, 15), that increase RdRp template binding and processivity. RdRp is also proposed to be the target of a class of antiviral drugs that are nucleotide analogs; this category includes remdesivir (16–18), which is a prodrug that is converted to the active drug in the triphosphate form [remdesivir triphosphate (RTP)] within cells (19). As such, RdRp has been the subject of intensive structural biology efforts. The structures of nsp7, nsp8, and the complex of nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 have been determined (15, 20–23), providing the overall architecture of the RdRp complex. However, the drug discovery effort is hampered because the structures of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp in complex with an RNA template and with nucleotide inhibitors are not known. In this study, we determined two cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex: one in the apo form and the other in a complex with a template-primer RNA and the antiviral drug remdesivir.

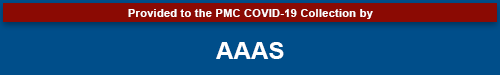

For cryo-EM studies, we coexpressed nsp12 with nsp7 and nsp8 to form the core RdRp complex in insect cells (Fig. 1A and fig. S1, A to D). The stoichiometric amount of nsp7 and nsp8 appeared to be less than that of nsp12, and thus additional bacterially expressed nsp7 and nsp8 were supplemented before the final purification step to improve the yield of heterotrimeric complex. The purified nsp12 alone showed little activity in binding to a 50-base partial double-stranded template-primer RNA (Fig. 1B and fig. S1E), which is similar to the SARS-CoV nsp12 (14). The presence of nsp7 and nsp8 markedly increased nsp12 binding to the template-primer RNA (fig. S1E). The nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex also showed RNA polymerization activity on a poly-U template upon addition of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Fig. 1, B and C). This RNA polymerization activity was effectively inhibited by the addition of RTP (Fig. 1D). Even in the presence of 10 mM ATP, which is within the range of physiological concentrations of ATP, 1 mM RTP completely inhibited RdRp polymerization activity. In addition, 100 µM RTP completely blocked the full extension but allowed partial extension of the primer RNA (Fig. 1D), consistent with a delayed chain termination mechanism (24). However, this mechanism is dependent on low RTP concentrations and low RTP/ATP ratios. By contrast, 5 mM remdesivir (as a prodrug) had no inhibitory effect on the polymerization activity of the purified enzyme (fig. S1F), nor did remdesivir in its monophosphate form (RMP) (fig. S1G).

Fig. 1. Assembly of an active nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 RdRp complex and its inhibition by remdesivir.

(A) Schematic diagram for the components of the RdRp complex, containing nsp12, nsp7, and nsp8. The polymerase motif (A to G) and the β hairpin specific to SARS-CoV-2 are highlighted. (B) Sequence of the RNA duplex with a 5′ U10 overhang as a template for primer extension and RdRp-RNA complex assembly. (C) The recombinant RdRp complex shows polymerase activity in vitro. The primer strand is labeled with fluorescence at the 5′ end. (D) Elongation of the partial RNA duplex by the purified RdRp complex and its inhibition by RTP.

The purified RdRp complex is relatively thermostable, with a melting temperature of 53°C (fig. S1H). Negative-stain EM visualization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex displayed monodispersed particles with excellent homogeneity (fig. S1I). For the apo nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex, we vitrified the sample in the presence of the detergent DDM. The initial attempt at image processing revealed that the particles are preferentially oriented (fig. S2A). Therefore, we collected >7400 micrograph movies of more than 5.7 million particle projections to increase the number of projections from the nonpreferential orientation. Of these, 81,494 particles were used to yield a density map of 2.8-Å resolution (fig. S2, B and E). Cryo-EM studies of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex bound with the template-primer RNA and RTP (termed the template-RTP RdRp complex) faced two challenges (fig. S3). First, most particles were adsorbed to cryo-EM grid bars rather than staying in the vitreous ice. Second, the RNA duplex was dissociated from the template-RTP RdRp complex, likely owing to conditions of cryo-EM specimen preparation. Eventually, we prepared the cryo-EM specimen of the template-RTP RdRp complex at 15 mg/ml, which is much higher than the normal concentrations used for EM studies of soluble protein complexes. The high concentration of the complex has a mass action effect to stabilize the RNA-protein complex and has an excess amount of the complex to escape the absorption of cryo-EM grid bars to enter the vitreous ice (fig. S3). We collected 2886 micrograph movies, which yielded a 2.5-Å resolution structure using 130,386 particle projections. Because of the relatively high resolution of our structure, the EM map is clear for key structural features across the complex (fig. S4, A to F).

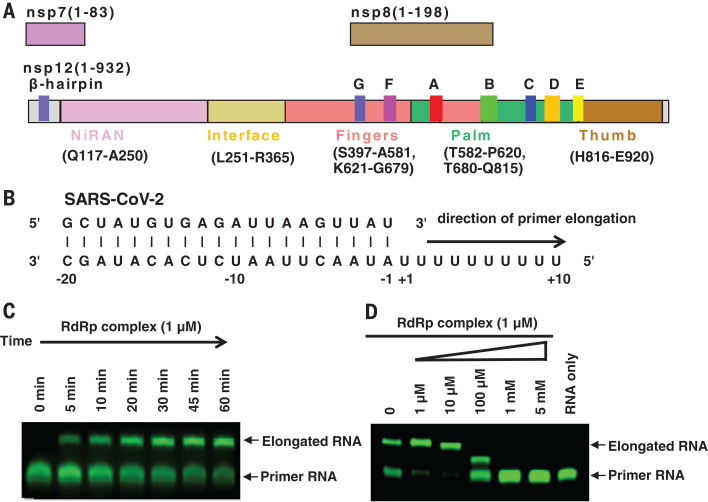

The structure of the apo RdRp complex contains one nsp12, one nsp7, and two nsp8 proteins, with an overall arrangement resembling those seen in SARS-CoV and the recently solved structure of SARS-CoV-2 (15, 23) (Fig. 2, A and B). Our structure, which differs from the SARS-CoV RdRp structure but is similar to the recent SARS-CoV-2 RdRp structure, reveals that nsp12 also contains an N-terminal β hairpin (residues 31 to 50) and an extended nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyl-transferase domain (NiRAN; residues 115 to 250) (24) with seven helices and three β strands (15, 23). After the NiRAN domain is an interface domain (residues 251 to 365), composed of three helices and five β strands, that is connected to the RdRp domain (residues 366 to 920) (Figs. 1A and 2B). The nsp12 RdRp domain displays the canonical cupped right-handed configuration (25), with the finger subdomain (residues 397 to 581 and 621 to 679) forming a closed circle with the thumb subdomain (residues 819 to 920) (Fig. 2, A and B). The closed conformation is stabilized by the binding of nsp7 and nsp8, with one nsp8 molecule sitting atop the finger subdomain and interacting with the interface domain. The closed conformation of nsp12 is further stabilized by the nsp7-nsp8 heterodimer, which is packed against the thumb-finger interface (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, we were able to assign two zinc ions in the conserved metal binding motifs composed of H295-C301-C306-C310 and C487-H642-C645-C646 (Fig. 2C), which are also observed in the SARS-CoV RdRp structure (15). These zinc ions likely function as conserved structural components in maintaining the integrity of the RdRp architecture.

Fig. 2. Cryo-EM structure of the apo nsp12-nsp-7-nsp8 RdRp complex.

(A and B) Two views of the cryo-EM map (A) and structure (B) of the apo nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex. The color scheme is according to Fig. 1A and is used throughout the figures. (C) The conserved zinc binding motifs are highlighted in the apo structure rendered in ribbon. The coordinate details of the zinc-binding residues are shown in stick representation, with the EM map in gray surface representation.

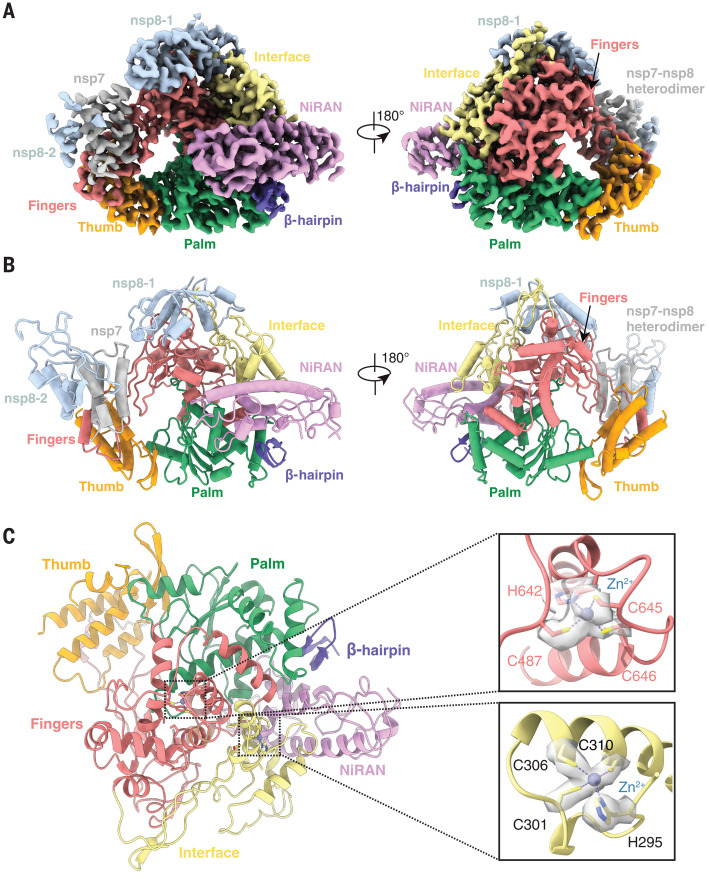

The structure of the template-RTP RdRp complex contains one nsp12, one nsp7, and one nsp8 (Fig. 3, A and B). The second nsp8 was largely invisible in the EM map of the template-RTP complex (fig. S4C); therefore, it was not included in the final model. In addition, the template-RTP RdRp structure contains 14-base RNA in the template strand, 11-base RNA in the primer strand, and the inhibitor RMP (Fig. 3, C and D), which is covalently linked to the primer strand, as well as a pyrophosphate and two magnesium ions that may serve as catalytic ions near the active site (Fig. 3D and fig. S4, D to F) (26).

Fig. 3. Cryo-EM structure of the remdesivir- and RNA-bound RdRp complex.

(A and B) Two views of the cryo-EM map (A) and structure (B) of nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 in complex with template-primer RNA and remdesivir. (C) Surface view of the RdRp active site with the electrostatic potential from red (negative) to blue (positive). For clarity, residues 410 to 442 and 834 to 919 of nsp12 and nsp8 are excluded from the figure. The covalently bound remdesivir in the monophosphate form and the product, pyrophosphate, are shown. The active site is emphasized with a yellow dashed circle. The template groove, the entrance for nucleotide triphosphate (NTP), and the elongation direction are annotated with different-colored arrows. (D) Close-up view of the RdRp active site, showing the covalently bound RMP, pyrophosphate, and magnesium ions. Key residues and bases that interact with remdesivir are shown. (E and F) Superposition of the conserved RdRp motifs (A to G) of the RNA-bound complex with the apo structure (colored in gray), with a close-up view at the active site (E) and at the exit of the template and primer strand (F).

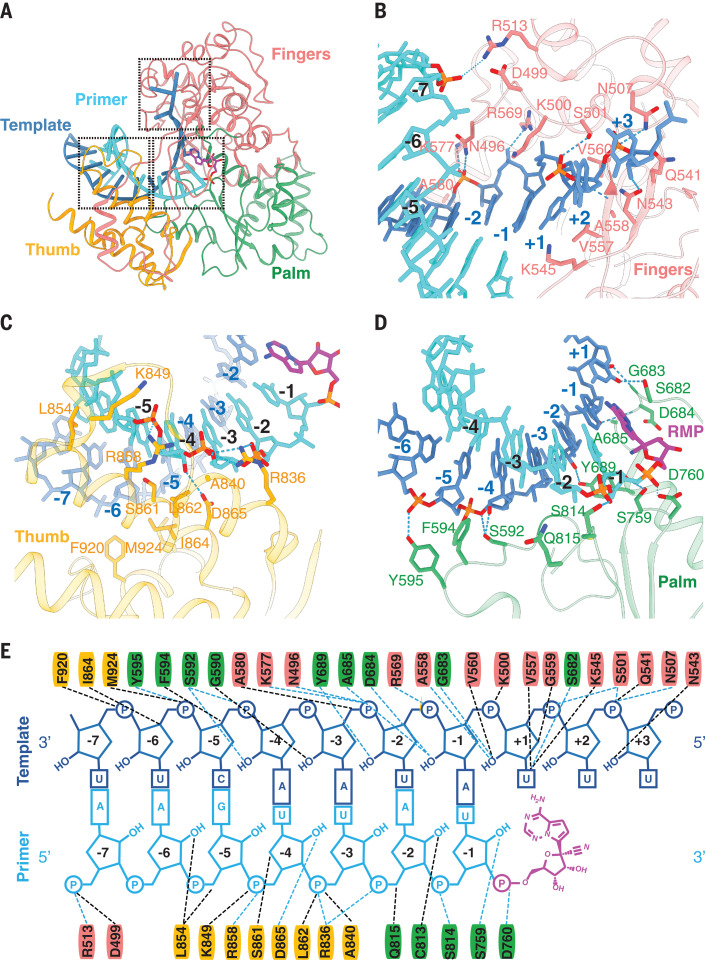

The overall structure of the template-RTP RdRp complex is similar to the apo RdRp structure, with nsp12 in a closed conformation (Figs. 2A and 3A). The double-stranded RNA helix, formed by 11 base pairs from the template-primer RNA (Figs. 3C and 4, A to E), is held by the finger-palm-thumb subdomains. Extensive protein-RNA interactions are observed between the template-primer RNA and nsp12, with a total of 41 residues from nsp12 directly participating in RNA binding (within 4.0 Å of RNA, 26 residues to the template strand and 15 residues to the primer strand; Fig. 4E). Surprisingly, no RNA interactions are mediated by nsp7 or nsp8, although these two proteins are required for RNA binding by RdRp. Most protein-RNA interactions involve the RNA phosphate-ribose backbones, with many interactions directly to 2′-OH groups (Fig. 4E), thus providing a basis to distinguish RNA from DNA. There are no contacts from nsp12 to any base pairs of the template-primer RNA, suggesting a sequence-independent binding of RNA by RdRp. This is consistent with the fact that no specific sequence is required for the enzymatic activity of RdRp at the elongation step.

Fig. 4. RNA recognition by the RdRp complex.

(A to D) Protein-RNA interactions in the RNA- and remdesivir-bound RdRp complex. (E) Diagram of detailed RNA interactions with RdRp. Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

At the 3′ end of the primer strand is RMP (Figs. 3D and 4, D and E, and fig. S4, E and F), which is covalently incorporated into the primer strand at the +1 position (Fig. 4E). Additional nucleotides at the +2 and +3 positions of the template strand interact with residues from the back of finger subdomain (Fig. 4, A and B). Despite the presence of excess RTP in complex assembly, only a single RMP is assembled into the primer strand, as observed in the structure. Consistent with the data from Fig. 1D, the primer extension is immediately terminated when RTP concentration is high and ATP/RTP ratio is low. Thus, remdesivir, like many nucleotide analog prodrugs, inhibits viral RdRp activity through nonobligate RNA chain termination, a mechanism that requires conversion of the parent drug to the active triphosphate form (27, 28).

The RMP position is at the center of the catalytic active site (Fig. 3D). As an adenosine monophosphate analog, RMP forms base-stacking interactions with an upstream base from the primer strand and two hydrogen bonds with the uridine base from the template strand (Fig. 3D and fig. S5). In addition, RMP forms interactions with side chains from K545 and R555. Near the bound RMP are two magnesium ions and a pyrophosphate. Both magnesium ions interact with the phosphate diester backbone and are part of the catalytic active site. The pyrophosphate is at the gate of the nucleotide entry channel to the active site and may block the entry of nucleotide triphosphate to the active side (Fig. 3, C and D).

The catalytic active site of the nsp12 RdRp consists of seven conserved motifs (A to G; Figs. 1A and 3E and fig. S6). Motifs A, B, C, and D are from the palm subdomain, with an SDD sequence (residues 759 to 761) in motif C forming the catalytic active center (Fig. 3D). Both D760 and D761 are involved in coordination of the two magnesium ions at the catalytic center. Motifs F and G are located within the finger subdomain; they interact with the template strand RNA and direct this strand into the active site (Fig. 3E). Motif F also interacts with the primer strand RNA, with the side chains of K545 and R555 contacting the +1 base (Fig. 3D) and thus stabilizing the incoming nucleotide in the correct position for catalysis. The orientation of template-primer RNA in the active site is similar to the orientation of template-primer RNA in the poliovirus RdRp elongation complex (29) and the hepatitis C virus NS5B RdRp inhibitor complex (30) (fig. S7). The residues involved in RNA binding and those that constitute the catalytic active site are highly conserved (31, 32), highlighting the conserved mechanism of genome replication by RdRp in these diverse RNA viruses and suggesting that it may be possible to develop broad-spectrum antiviral inhibitors such as remdesivir (18) and galidesivir (BCX4430) (33).

Structural comparison reveals several notable differences between the apo and complex structures (Fig. 3, E and F, and fig. S8, A and B). First, nsp7 moves toward the RdRp core by 1.5 Å (as measured by nsp7 residue F49; fig. S8, A and B), leading to a rearrangement of the interface, which results in weaker association of the second nsp8 in the complex. Second, the loop that connects the first and second helices of the thumb subdomain moves outward by 2.8 Å (as measured by nsp12 residue I847) to accommodate the binding of the double-stranded RNA helix (Fig. 3F). Third, motif G residues K500 and S501 also move outward by 2.0 Å to accommodate the binding of the template-strand RNA. Outside of these changes, the apo nsp12 and the RNA complex nsp12 are very similar, with a root mean square deviation of 0.52 Å for all Cα atoms across the whole protein. In particular, the structural elements that make up the catalytic active site can be precisely superimposed (Fig. 3E), which suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp is a relatively stable enzyme that is ready to function as a replicase upon RNA template binding. Viral RdRp is a highly processive enzyme with a replication rate of up to 100 nucleotides per second (34). No substantial conformational changes between the apo and active enzyme structures are consistent with the high processivity of the viral RNA polymerase, which does not need to consume additional energy for conformational changes in the active site during the replication cycle.

Besides remdesivir, several nucleotide analog drugs—including favipiravir, ribavirin, galidesivir, and EIDD-2801—efficiently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in cell-based assays (35, 36). Like remdesivir, these nucleotide analogs are proposed to inhibit the viral RdRp through nonobligate RNA chain termination, a mechanism that requires conversion of the parent compound to the triphosphate active form (33). The structure of the template-RTP RdRp complex provides a useful model to rationalize how these drugs inhibit the activity of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (fig. S8C). In particular, EIDD-2801 has been shown to be 3 to 10 times as potent as remdesivir in blocking SARS-CoV-2 replication (36). The N4 hydroxyl group off the cytidine ring forms an extra hydrogen bond with the side chain of K545, and the cytidine base also forms an extra hydrogen bond with the guanine base from the template strand. These two extra hydrogen bonds may explain the apparent higher potency of EIDD-2801 in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication.

The COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted emotional pain and economic burden across the globe. Enzymes that are vital for the viral life cycle are suitable antiviral drug targets because they differ from host proteins. Among viral enzymes, RdRp is the primary target of many existing nucleotide drugs. In this paper, we report the structures of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex in the apo form as well as in complex with a template-primer RNA and the active form of remdesivir. The structures reveal how the template-primer RNA is recognized by the enzyme and how chain elongation is inhibited by remdesivir. Structure comparison and sequence alignment suggest that the mode of substrate RNA recognition and remdesivir inhibition of RdRp is highly conserved in diverse RNA viruses, providing a foundation for designing broad-spectrum antiviral drugs based on nucleotide analogs. Moreover, our structures provide a solid template for modeling and modifying the existing nucleotide drugs, including the highly potent EIDD-2801. Together, these observations provide a rational basis to design even more potent inhibitors to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Acknowledgments

The cryo-EM data were collected at the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy, Zhejiang University. We thank MedChemExpress for making remdesivir. We also thank J. Richardson, D. Richardson, and T. Croll for help with validating the structures. Funding: This work was partially supported by the National Key R&D Programs of China 2018YFA0507002; Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project 2019SHZDZX02 and XDB08020303 to H.E.X.; Zhejiang University special scientific research fund for COVID-19 prevention and control E33 and the National Science Foundation of China 81922071 to Y.Z.; Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipal 20431900100 and Jack Ma Foundation 2020-CMKYGG-05 to H.J. and J.S.; CAMS Innovation Fund for “13th Five-Year” National Science and Technology Major Project for New Drugs 2019ZX09734001-002, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences no. 2020-I2M-CoV19-001, and Tsinghua University–Peking University Center for Life Sciences 045-160321001 to S.Z.; National Key Research and Development Program of China grant 2016YFA0500600 and National Natural Science Foundation of China 31970130 and 3167083 to S.-C.T.; National Key R&D Program of China 2016YFA0502301 to Y.X.; and National Natural Science Foundation 31770796 and National Science and Technology Major Project 2018ZX09711002 to Y.J. Author contributions: W.Y. designed the expression constructs, purified the RdRp complex, prepared samples for negative-stain EM and data collection toward the structures, and participated in figure and manuscript preparation. X.L. designed RdRp activity assays and remdesivir inhibition experiments as well as expression constructs of the RdRp complex. C.M. and D.-D.S. evaluated the specimen by negative-stain EM, screened the cryo-EM conditions, prepared the cryo-EM grids, and collected cryo-EM images with the help of S.C.; D.-D.S. and C.M. also performed density map calculations. Q.S., H.S., and W.Z. participated in model building and refined the final models. H.-W.J. and S.-C.T. provided nsp7 and nsp8 genes. X.W., F.Z., and M.G. participated in expression, purification, and functional assays of the RdRp. Y.-C.X., G.T., and J.S. made the remdesivir triphosphate form. Y.J. participated in experimental design and manuscript editing. H.J. conceived and coordinated the project. S.Z. conceived the project, initiated collaboration with H.E.X., and supervised X.L. Y.X. analyzed the structure and modeling and participated in figure preparation. Y.Z. supervised Q.S., C.M., and D.-D.S; analyzed the structures; and participated in manuscript writing. H.E.X. conceived and supervised the project, analyzed the structures, and wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Density maps and structure coordinates have been deposited for immediate release. The Electron Microscopy Data Bank accession numbers and Protein Data Bank identifiers are EMD-30209 and PDB ID 7BV1 for the apo RdRp complex and EMD-30210 and PDB ID 7BV2 for the template RNA and remdesivir–bound RdRp complex. Materials are available upon request. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This license does not apply to figures/photos/artwork or other content included in the article that is credited to a third party; obtain authorization from the rights holder before using such material.

Supplementary Materials

Correction (25 June 2020): After the initial online publication of the paper, the structures for Protein Data Bank (PDB) IDs 7BV1 and 7BV2 were updated, with corrections in the C-terminal fragment of nsp12 (residues 911 to 929) and removal of the third magnesium ion. As such, Figs. 3E and 4 have also been updated, along with the corresponding text.

References and Notes

- 1.Gorbalenya A. E., Baker S. C., Baric R. S., de Groot R. J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A. A., Haagmans B. L., Lauber C., Leontovich A. M., Neuman B. W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L. L. M., Samborskiy D. V., Sidorov I. A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J.; Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses , The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 536–544 (2020). 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L., An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 533–534 (2020). 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.-J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L., A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam T. T.-Y., Shum M. H.-H., Zhu H.-C., Tong Y.-G., Ni X.-B., Liao Y.-S., Wei W., Cheung W. Y.-M., Li W.-J., Li L.-F., Leung G. M., Holmes E. C., Hu Y.-L., Guan Y., Identifying SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z., Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak. Curr. Biol. 30, 1346–1351.e2 (2020). 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q., Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367, 1444–1448 (2020). 10.1126/science.abb2762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Goldsmith J. A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020). 10.1126/science.abb2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X., Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215–220 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F., Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221–224 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walls A. C., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M. A., Wall A., McGuire A. T., Veesler D., Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292.e6 (2020). 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziebuhr J., The coronavirus replicase. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 287, 57–94 (2005). 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn D. G., Choi J. K., Taylor D. R., Oh J. W., Biochemical characterization of a recombinant SARS coronavirus nsp12 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase capable of copying viral RNA templates. Arch. Virol. 157, 2095–2104 (2012). 10.1007/s00705-012-1404-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.te Velthuis A. J., Arnold J. J., Cameron C. E., van den Worm S. H., Snijder E. J., The RNA polymerase activity of SARS-coronavirus nsp12 is primer dependent. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 203–214 (2010). 10.1093/nar/gkp904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subissi L., Posthuma C. C., Collet A., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J. C., Gorbalenya A. E., Decroly E., Snijder E. J., Canard B., Imbert I., One severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus protein complex integrates processive RNA polymerase and exonuclease activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E3900–E3909 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1323705111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchdoerfer R. N., Ward A. B., Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat. Commun. 10, 2342 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-10280-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G., Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 30, 269–271 (2020). 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holshue M. L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K. H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A., Diaz G., Cohn A., Fox L., Patel A., Gerber S. I., Kim L., Tong S., Lu X., Lindstrom S., Pallansch M. A., Weldon W. C., Biggs H. M., Uyeki T. M., Pillai S. K.; Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team , First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 929–936 (2020). 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren T. K., Jordan R., Lo M. K., Ray A. S., Mackman R. L., Soloveva V., Siegel D., Perron M., Bannister R., Hui H. C., Larson N., Strickley R., Wells J., Stuthman K. S., Van Tongeren S. A., Garza N. L., Donnelly G., Shurtleff A. C., Retterer C. J., Gharaibeh D., Zamani R., Kenny T., Eaton B. P., Grimes E., Welch L. S., Gomba L., Wilhelmsen C. L., Nichols D. K., Nuss J. E., Nagle E. R., Kugelman J. R., Palacios G., Doerffler E., Neville S., Carra E., Clarke M. O., Zhang L., Lew W., Ross B., Wang Q., Chun K., Wolfe L., Babusis D., Park Y., Stray K. M., Trancheva I., Feng J. Y., Barauskas O., Xu Y., Wong P., Braun M. R., Flint M., McMullan L. K., Chen S.-S., Fearns R., Swaminathan S., Mayers D. L., Spiropoulou C. F., Lee W. A., Nichol S. T., Cihlar T., Bavari S., Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature 531, 381–385 (2016). 10.1038/nature17180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel D., Hui H. C., Doerffler E., Clarke M. O., Chun K., Zhang L., Neville S., Carra E., Lew W., Ross B., Wang Q., Wolfe L., Jordan R., Soloveva V., Knox J., Perry J., Perron M., Stray K. M., Barauskas O., Feng J. Y., Xu Y., Lee G., Rheingold A. L., Ray A. S., Bannister R., Strickley R., Swaminathan S., Lee W. A., Bavari S., Cihlar T., Lo M. K., Warren T. K., Mackman R. L., Discovery and Synthesis of a Phosphoramidate Prodrug of a Pyrrolo[2,1-f][triazin-4-amino] Adenine C-Nucleoside (GS-5734) for the Treatment of Ebola and Emerging Viruses. J. Med. Chem. 60, 1648–1661 (2017). 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhai Y., Sun F., Li X., Pang H., Xu X., Bartlam M., Rao Z., Insights into SARS-CoV transcription and replication from the structure of the nsp7-nsp8 hexadecamer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 980–986 (2005). 10.1038/nsmb999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peti W., Johnson M. A., Herrmann T., Neuman B. W., Buchmeier M. J., Nelson M., Joseph J., Page R., Stevens R. C., Kuhn P., Wüthrich K., Structural genomics of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the protein nsP7. J. Virol. 79, 12905–12913 (2005). 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12905-12913.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M. A., Jaudzems K., Wüthrich K., NMR Structure of the SARS-CoV Nonstructural Protein 7 in Solution at pH 6.5. J. Mol. Biol. 402, 619–628 (2010). 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y., Yan L., Huang Y., Liu F., Zhao Y., Cao L., Wang T., Sun Q., Ming Z., Zhang L., Ge J., Zheng L., Zhang Y., Wang H., Zhu Y., Zhu C., Hu T., Hua T., Zhang B., Yang X., Li J., Yang H., Liu Z., Xu W., Guddat L. W., Wang Q., Lou Z., Rao Z., Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science 368, 779–782 (2020). 10.1126/science.abb7498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehmann K. C., Gulyaeva A., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J. C., Janssen G. M. C., Ruben M., Overkleeft H. S., van Veelen P. A., Samborskiy D. V., Kravchenko A. A., Leontovich A. M., Sidorov I. A., Snijder E. J., Posthuma C. C., Gorbalenya A. E., Discovery of an essential nucleotidylating activity associated with a newly delineated conserved domain in the RNA polymerase-containing protein of all nidoviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 8416–8434 (2015). 10.1093/nar/gkv838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald S. M., RNA synthetic mechanisms employed by diverse families of RNA viruses. WIREs RNA 4, 351–367 (2013). 10.1002/wrna.1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hemert M. J., van den Worm S. H. E., Knoops K., Mommaas A. M., Gorbalenya A. E., Snijder E. J., SARS-coronavirus replication/transcription complexes are membrane-protected and need a host factor for activity in vitro. PLOS Pathog. 4, e1000054 (2008). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tchesnokov E. P., Feng J. Y., Porter D. P., Götte M., Mechanism of Inhibition of Ebola Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase by Remdesivir. Viruses 11, 326 (2019). 10.3390/v11040326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon C. J., Tchesnokov E. P., Woolner E., Perry J. K., Feng J. Y., Porter D. P., Götte M., Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 6785–6797 (2020). 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong P., Peersen O. B., Structural basis for active site closure by the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22505–22510 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1007626107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Appleby T. C., Perry J. K., Murakami E., Barauskas O., Feng J., Cho A., Fox D. 3rd, Wetmore D. R., McGrath M. E., Ray A. S., Sofia M. J., Swaminathan S., Edwards T. E., Structural basis for RNA replication by the hepatitis C virus polymerase. Science 347, 771–775 (2015). 10.1126/science.1259210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.te Velthuis A. J., Common and unique features of viral RNA-dependent polymerases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 4403–4420 (2014). 10.1007/s00018-014-1695-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkataraman S., Prasad B. V. L. S., Selvarajan R., RNA Dependent RNA Polymerases: Insights from Structure, Function and Evolution. Viruses 10, 76 (2018). 10.3390/v10020076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren T. K., Wells J., Panchal R. G., Stuthman K. S., Garza N. L., Van Tongeren S. A., Dong L., Retterer C. J., Eaton B. P., Pegoraro G., Honnold S., Bantia S., Kotian P., Chen X., Taubenheim B. R., Welch L. S., Minning D. M., Babu Y. S., Sheridan W. P., Bavari S., Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature 508, 402–405 (2014). 10.1038/nature13027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campagnola G., McDonald S., Beaucourt S., Vignuzzi M., Peersen O. B., Structure-function relationships underlying the replication fidelity of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. J. Virol. 89, 275–286 (2015). 10.1128/JVI.01574-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu C.-C., Chen M.-Y., Chang Y.-L., Potential therapeutic agents against COVID-19: What we know so far. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000318 (2020). 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheahan T. P., Sims A. C., Zhou S., Graham R. L., Pruijssers A. J., Agostini M. L., Leist S. R., Schäfer A., Dinnon K. H. 3rd, Stevens L. J., Chappell J. D., Lu X., Hughes T. M., George A. S., Hill C. S., Montgomery S. A., Brown A. J., Bluemling G. R., Natchus M. G., Saindane M., Kolykhalov A. A., Painter G., Harcourt J., Tamin A., Thornburg N. J., Swanstrom R., Denison M. R., Baric R. S., An orally bioavailable broad-spectrum antiviral inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cell cultures and multiple coronaviruses in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabb5883 (2020). 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb5883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng S. Q., Palovcak E., Armache J.-P., Verba K. A., Cheng Y., Agard D. A., MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K., Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016). 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheres S. H., RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012). 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heymann J. B., Guidelines for using Bsoft for high resolution reconstruction and validation of biomolecular structures from electron micrographs. Protein Sci. 27, 159–171 (2018). 10.1002/pro.3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E., UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004). 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L.-W., Jain S., Kapral G. J., Grosse Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R. D., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H., The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods 55, 94–106 (2011). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soon F. F., Suino-Powell K. M., Li J., Yong E.-L., Xu H. E., Melcher K., Abscisic acid signaling: Thermal stability shift assays as tool to analyze hormone perception and signal transduction. PLOS ONE 7, e47857 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0047857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harder E., Damm W., Maple J., Wu C., Reboul M., Xiang J. Y., Wang L., Lupyan D., Dahlgren M. K., Knight J. L., Kaus J. W., Cerutti D. S., Krilov G., Jorgensen W. L., Abel R., Friesner R. A., OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 281–296 (2016). 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.