Introduction

Lichen planus pemphigoides is an uncommon autoimmune blistering disease characterized by clinical and microscopic findings of lichen planus, and a subepidermal blistering disease with antibodies to the basement membrane, similar to bullous pemphigoid. The disease is rare in adults and rarer in pediatric patients, with only 17 cases described so far.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 It is usually idiopathic, although it has been related to some drugs in adults. As for children, lichen planus pemphigoides has been related to varicella infections2,3 and has been triggered by henna tattoos5 and the excessive application of an aromatic retinoid.7 To our knowledge, this is the first case of pediatric erythrodermic lichen planus pemphigoides described after nonavalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Case report

An 11-year-old boy presented with an extremely pruritic, diffuse rash for 7 weeks. The eruption started 2 weeks after he received the first dose of HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9), with isolated papules that coalesced into a widespread dermatitis. He had a history of atopic dermatitis, was up to date on all vaccines, and was receiving no medication. Physical examination found dry erythroderma involving more than 90% of his body surface according to the Wallace rule of 9, with the presence of purplish papules on the face, neck, trunk, and upper and lower extremities, including palms and soles, as well as tense hemorrhagic blisters on his legs and feet. Vesiculobullous lesions were present both on the papules and on normal skin, appearing 5 weeks after the development of papules (Figs 1 and 2). Mucous membranes and nails were spared. Nikolsky sign was negative. Histologic examination of a lichenoid lesion from the thigh showed hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis, focal hypergranulosis, and acanthosis with some apoptotic keratinocytes, interface dermatitis with a dense lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes, and rare eosinophils (Fig 3), whereas histopathology of a bullous lesion on the leg revealed a subepidermal blister containing eosinophils and neutrophils in the blister fluid and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis (Fig 4). Direct immunofluorescence showed linear C3 deposits along the basement membrane. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from serum was positive for PB180 antibody (120 U/mL; normal <9 U/mL) and slightly positive for PB230 antibody (10.50 U/mL; normal <9 U/mL). A diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides was made. The patient was treated with oral deflazacort 1.5 mg/kg/day, antihistamines, and topical steroids, with rapid improvement and clearing of the pruritic eruption. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient's parents were advised to avoid further HPV vaccine injections to their son.

Fig 1.

Dry erythroderma with the presence of purplish isolate confluent buttocks and papules on the trunk and upper and lower extremities, including palms and soles.

Fig 2.

Dry erythematous patches with vesiculobullous elements.

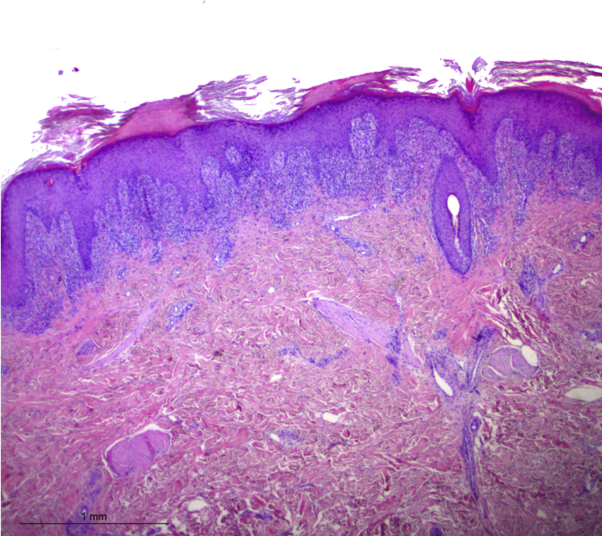

Fig 3.

Histopathology of a papule showing hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis, focal hypergranulosis, acanthosis with some apoptotic keratinocytes, interface dermatitis with a dense lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes, and rare eosinophils. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×25.)

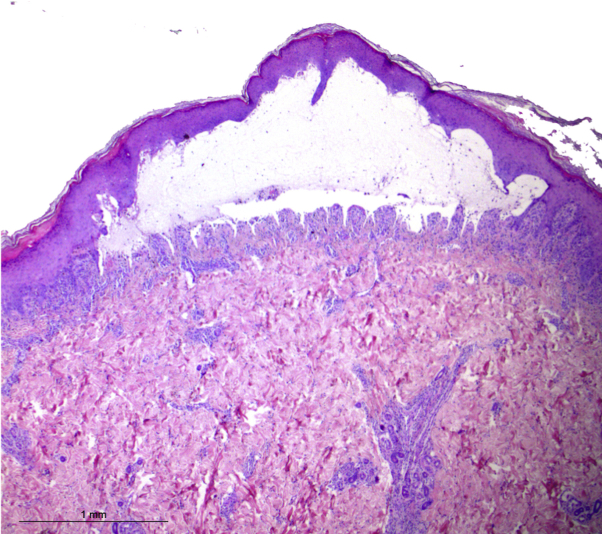

Fig 4.

Histopathology of a bullous lesion from the leg, revealing a subepidermal blister containing eosinophils, neutrophils, and a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×25.)

Discussion

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare, autoimmune, subepidermal bullous disease characterized by the coexistence of both lichen planus and bullous pemphigoid, although the relationship between these 2 disorders is more complex. Clinical findings include 2 primary skin lesions (ie, lichenoid papules and plaques and tense subepidermal blisters located both on the lichenoid plaques and on the uninvolved skin),8, 9, 10 different from bullous lichen planus, in which bullae are limited to long-standing lichen planus lesions. The onset of lichenoid lesions usually precedes the onset of bullae. Mucosal and nail involvement may occur but is uncommon. Palmoplantar involvement is observed more often in children. The erythrodermic form is rare, being reported in just 11 cases in adults but in only 1 case in pediatric patients. The pathogenesis of lichen planus pemphigoides can be explained by the phenomenon of “epitope spreading.” It has been hypothesized that a lichenoid inflammatory attack to the basal cell layers and basal membrane can expose antigens and promote the development of an autoimmune response, targeting proteins of the epidermal basement membrane, including type XVII collagen, also known as PB180 antigen.11,12

Although usually idiopathic, lichen planus pemphigoides has been related to drugs such as cinnarizine, captopril, ramipril, simvastatin, antituberculous medications, gliptins, nivolumab, and enalapril; to phototherapy; and rarely to malignancies. Lichen planus pemphigoides has also been reported to be triggered by viral infections such as varicella,2,3 hepatitis B virus,13,14 and pharyngitis in the only pediatric case of erythrodermic lichen planus pemphigoides.6 Gardasil 9 is the nonavalent HPV vaccine licensed in 2014 that contains an additional 5 cancer-causing HPV types (HPV31, -33, -45, -52, and -58) in addition to the 4 more common HPV types (HPV16, -18, -6, and -11).15 It has twice the concentration (500 mg) of aluminum hydroxyphosphate as an adjuvant16 compared with 4-valent HPV vaccine.

Adverse events to HPV vaccination have been previously reported, including local reactions at the injection site such as granulomas, lipoatrophy, cellulitis, subcutaneous emphysema mainly related to the aluminum vaccine content, erythema multiforme, dermographism, urticaria, erythema nodosum, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis.17, 18, 19 A lichenoid eruption after HPV vaccine has also been described.20 To our knowledge, this is the first case of lichen planus pemphigoides in its erythrodermic variant after nonavalent HPV vaccination (Gardasil 9). In our patient, for ethical reasons, we could not perform a rechallenge, but the pattern of lichenoid reaction followed by the appearance of the bullae, the temporal relationship between the development of lichen planus pemphigoides and the vaccination, and the complete healing of the eruption suggest that the HPV vaccine was the probable triggering event.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Cohen D.M., Ben-Amitai D., Feinmesser M. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohanarao T.S., Kumar G.A., Chennamsetty K. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S98–S100. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.146169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilknur T., Akarsu S., Uzun S. Heterogeneous disease: a child case of lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by varicella. J Dermatol. 2011;38:707–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duong B., Marks S., Sami N. Lichen planus pemphigoides in a 2-year-old girl: response to treatment with methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:e154–e156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldscheider I., Herzinger T., Varga R. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides: report of two cases treated successfully with systemic glucocorticoids and dapsone. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:751–753. doi: 10.1111/pde.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maouni S., Ouiam E.A., Asmae S. A pediatric case of erythrodermic lichen planus pemphigoides. J Clin Trials. 2019;8:359. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierini A.M., Bussy R.F., Souteryand P. Liquen plano ampollar: estudio de dos casos infantiles y revision de la inmunopatologia. Bullous lichen planus. Study of two cases in children and review of immunopathologyArch Argent Dermatol. 1981;31:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubner F., Langan E.A., Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archer C.B., Cronin E., Smith N.P. Diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides in the absence of bullae on normal-appearing skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:433–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaraa I., Mahfoudh A., Sellami M.K. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matos-Pires E., Campos S., Lencastre A. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335–337. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13434_g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan L.S., Vanderlugt C.J., Hashimoto T. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;8:331–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang S.H., Yun S.J., Lee S.C. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:868–871. doi: 10.1111/ced.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flageul B., Hassan F., Pinquier L. Lichen pemphigoid associated with developing hepatitis B in a child. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126(8-9):604–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toh Z.Q., Kosasih J., Russell F.M. Recombinant human papillomavirus nonavalent vaccine in the prevention of cancers caused by human papillomavirus. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1951–1967. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S178381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cervantes J.L., Doan A.H. Discrepancies in the evaluation of the safety of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2018;113:e180063. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760180063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longueville C., Doffoel-Hantz V., Hantz S. Gardasil®-induced erythema nodosum. Rev Med Interne. 2012;33:17–18. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeya S., Uirano S., Tokura Y. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis following human papillomavirus vaccination. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:787–788. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoulis A.C., Liakou A., Bozi E. Erythema multiforme following vaccination for human papillomavirus. Dermatology. 2010;220:60–62. doi: 10.1159/000254898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laschinger M.E., Schleichert R.A., Green B. Lichenoid drug eruption after human papillomavirus vaccination. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e48. doi: 10.1111/pde.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]