Abstract

Background:

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is a hereditary heart disease characterized by fatty infiltration, life-threatening arrhythmias and increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). The guideline for management of ARVC patients is to improve quality of life by reducing arrhythmic symptoms and to prevent SCD. However, the mechanism underlying ARVC-associated cardiac arrhythmias remains poorly understood.

Methods:

Using protein mass spectrometry analyses, we identified integrin β1 is down-regulated in ARVC hearts without changes to Ca2+-handling proteins. As adult cardiomyocytes express only the β1D isoform, we generated a cardiac specific β1D knockout (β1D−/−) mouse model, and performed functional imaging and biochemical analyses to determine the consequences from integrin β1D loss of function in the heart in vivo and in vitro.

Results:

Integrin β1D deficiency and RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation were detected by western blotting in left ventricular tissues from patients with ARVC but not in patients with ischemic or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Using lipid bilayer patch clamp single channel recordings, we found purified integrin β1D protein could stabilize RyR2 function by decreasing RyR2 open probability (Po), mean open time (To), and increasing mean close time (Tc). β1D−/− mice exhibited normal cardiac function and morphology, but presented with catecholamine-sensitive polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, consistent with increased RyR2 Ser-2030 phosphorylation and aberrant Ca2+ handling in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes. Mechanistically, we revealed that loss of desmoplakin induces integrin β1D deficiency in ARVC mediated through an ERK1/2 – fibronectin – ubiquitin/lysosome pathway.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that integrin β1D deficiency represents a novel mechanism underlying the increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ARVC.

Keywords: ARVC, catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia, mechanism, integrin β1D, RyR2 phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is a rare hereditary progressive heart disease characterized by fibrous or fatty infiltration of the heart muscle with predominantly right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD).1 As left ventricular (LV) involvement is found more commonly than previously appreciated in patients with ARVC, ARVC is increasingly recognized as a biventricular entity.2, 3 A recent study indicates that LV involvement in ARVC may even precede the onset of significant RV dysfunction and is associated with a higher prevalence of ventricular arrhythmia.3 In adolescents and young adults with ARVC, especially in athletic individuals in the absence of previous reported cardiac symptoms, exercise or competitive sports is a critical factor that may trigger fatal ventricular arrhythmias and increase the risk of SCD.3, 4 Exercise-induced catecholamine release is a major trigger linking the onset of ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in athletes with ARVC.5, 6

ARVC is associated with mutations in the genes encoding desmosomal proteins including desmoplakin (DSP), plakophilin 2 (PKP2), desmoglein 2 (DSG2), and desmocollin 2 (DSC2).7–9 Mutation-associated electrical uncoupling between cardiomyocytes from fibrofatty tissue replacement of the myocardium in ARVC is thought to be the main mechanism underlying ventricular arrhythmias. The fibro-fatty tissues in affected ventricles may provide a substrate for ventricular tachycardia through a re-entry mechanism.9–11

ARVC is distinct from catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (or CPVT), another type of familial hereditary arrhythmogenic disease. Although both are life threatening, CPVT occurs in individuals with structurally normal hearts, characterized by exercise induced bidirectional/polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.12 CPVT originates from dysregulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis. The pathogenic mediators of CPVT include mutations in genes associated with intracellular calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) such as the ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2), calsequestrin-2 (CASQ2), triadin (TRDN) and calmodulin (CALM1).13–18 Mutations in these genes cause defects in RyR2 activities, abnormal Ca2+ handling and triggered activities, which are exacerbated under sympathetic stress or exercise.13, 17, 19 It is generally agreed that ARVC and CPVT are caused by mutations of different sets of genes involved in distinct molecular and cellular functions within cardiomyocytes.

Interestingly, new lines of evidence from both clinical and animal experimental data indicate there is some degree of convergence (overlap) between ARVC and CPVT. First, mutations in the RyR2 gene were found in a well clinically characterized cohort of ARVC patients without mutations in desmosomal genes with a frequency of 9%.20 Second, PKP2 mutations were identified in a significant percentage (5 out of 18, 27.7%) of a clinically diagnosed CPVT patient cohort whose genetic testing panels reported negative on mutations of conventional CPVT genes.4 In these patients, cardiac imaging or autopsy demonstrated structurally normal hearts at the time of diagnosis or death. Third, in a case report of a young patient with a clinical diagnosis of typical ARVC but negative for mutations of known genes associated with both CPVT and ARVC, showed classic bi-directional and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during exercise stress testing.21 Fourth, like CPVT, exercise or exertion is a risk factor of ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in ARVC patients with more clinical studies supporting the diagnostic value of isoproterenol testing in ARVC.22, 23 Fifth, in an animal model, Cerrone et al. reported that cardiac-specific deletion of Pkp2 in mice leads to reduced expression of genes related to intracellular Ca2+ handling, i.e., Ryr2 and Trdn, and higher vulnerability to isoproterenol-triggered polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias that mimics CPVT.24 These findings collectively suggest that CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias are often present in ARVC. However, the molecular mechanism by which ARVC-associated mutations give rise to CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias (i.e., catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia), in the absence of canonical CPVT gene mutations, has been a longstanding mystery.

In the present study, using protein mass spectrometry analyses, we identified integrin β1, but not other Ca2+-handling proteins, is significantly down-regulated in left ventricles of ARVC patients. Integrin β1 is composed of 4 isoforms, including β1A, B, C & D. Integrin β1D is mainly expressed in striated muscles, including heart muscle, and is the only isoform expressed in adult cardiomyocytes.25, 26 Using a cardiac specific β1D knockout (β1D−/−) mouse model, we further show that integrin β1D deficiency represents an important mechanism underlying Ca2+ disorders and fatal catecholaminergic-sensitive Ca2+-dependent ventricular arrhythmias in ARVC.

METHODS

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be/have been made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. Requests for reagents and materials may be sent to the corresponding authors.

All studies involving human tissues strictly abided by the principles outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.27 All procedures involving human tissues were approved by Fuwai Hospital (Beijing, China). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85 – 23, revised 1985) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fuwai Hospital.

Human heart samples

Human LV samples from patients with ARVC, ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) were obtained from explanted hearts through the Fuwai Hospital Heart Failure Transplant Program. A total of 4 non-failing healthy donor (HD) hearts without evidence of cardiac dysfunction were obtained through organ procurement agencies. Patient demographics, and corresponding clinic information of ARVC, ICM and HCM are detailed in Supplemental Table 1,2,3.

Generation of integrin β1D knockout mouse model

Itgb1 flox/flox (Itgb1f/f) mice with LoxP sites inserted between canonical exon 15 and exon 16 flanking the alternatively spliced and cardiomyocyte specific “D” exon26 were generated by the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. Tamoxifen‐inducible Cre‐Lox mice (αMHC‐MerCreMer, or αMHC-MCM) were obtained from the same center. Itgb1f/f mice were bred with αMHC-MCM mice to generate experimental cohorts including cardiac-specific Itgb1 homozygous knockout mice (β1D−/−, Cre+/Itgb1f/f) and wildtype (WT, Cre−/Itgb1f/f) littermates. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with tamoxifen (40 mg/kg body weight, Sigma Aldrich, USA, dissolved in corn oil) or with corn oil only (control group) for 10 days. Expression levels of integrin β1D were assessed by western blotting with heart tissues collected at 1 week and 2 weeks after the last dose of tamoxifen injection. All experiments were performed in mice two weeks after the last dose of tamoxifen injection (~9–11 weeks old). The numbers of mice or myocytes for each experimental group are provided in the Figures and/or Figure Legends.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics Version 22. Differences between groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test or χ2 test. The data represent the means ± SEM. *P <0.05, **P <0.01 and ***P <0.001 were considered statistically significant.

All detailed experimental methods can be found in the online-only Supplemental Materials.

RESULTS

Integrin β1D expression is decreased together with RyR2 hyper-phosphorylation in left ventricle tissues from patients with ARVC, but not in patients with ICM and HCM.

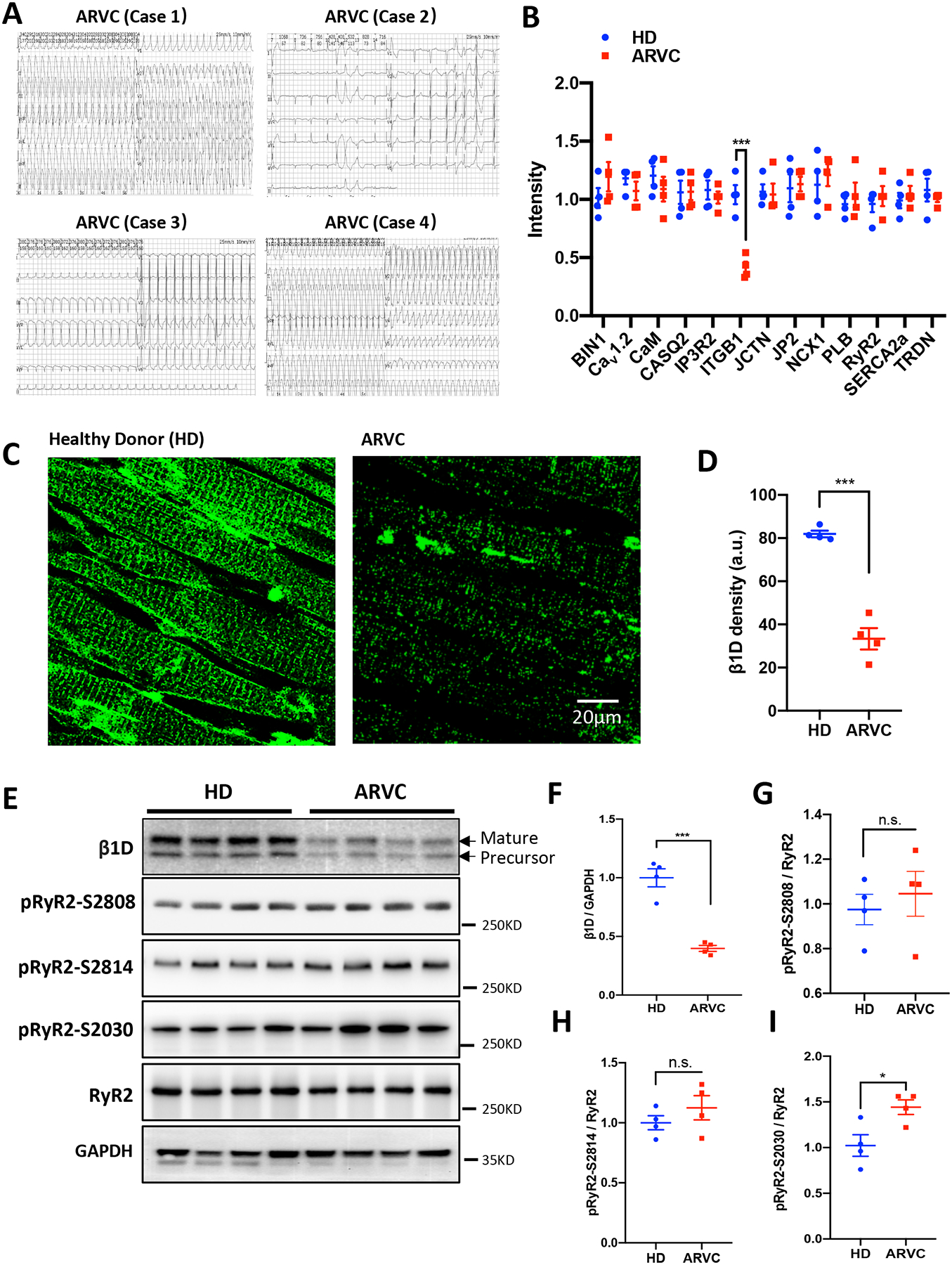

We followed 39 patients who were diagnosed with ARVC according to the 2010 Task Force Criteria (TFC).28 For the studies presented here, LV tissue samples were processed from the four patients who had successfully undergone cardiac transplantation (Supplemental Figure 1). All patients had severe, emotional excitement- or exercise-induced ventricular tachycardias that were not present at rest. (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 2). MRI reported fibrofatty infiltration of RV predominance with LV involvement in all four patients (Supplemental Figure 3). Whole exon sequencing found three patients had mutations in desmosomal genes including desmoglein-2 (DSG2 F531C; Case 1), plakophilin-2 (PKP2 C796R; Case 2) and desmoplakin (DSP S299R; Case 4) genes (Figure S3). Using protein mass spectrometry analyses, we found that integrin β1 is significantly down-regulated in LV hearts from patients with ARVC, but no change in other Ca2+-handling proteins including Amphyphisin-2 (Bin1), L-type Ca2+ channel (CaV1.2), calmodulin (CaM), IP3R, junctin (JCTN), junctophilin-2 (JP2), sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX1), phospholamban (PLB), RyR2, SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) and triadin (TRDN), as compared to these of healthy donor hearts (HD) (Figure 1B). The expression levels of membrane ion channels such as sodium and potassium channels remained unaltered in LV hearts of ARVC, as compared to HDs (Supplemental Figure 4). Immunofluorescent confocal images of LV heart cryosections from healthy donors and ARVC patients demonstrate that integrin β1D is regularly distributed in a striated pattern, like T-tubules, in control myocardium but markedly reduced in intensity in ARVC (Figures 1C–D). Previous work has suggested that integrin β1D is present at intercalated discs and T-tubules in mouse and rat hearts,25, 26 and co-localizes with and regulates RyR2 phosphorylation levels at its Serine 2808 (Ser-2808) site in cardiomyocytes.29 These led us to hypothesize that integrin β1D downregulation may contribute to RyR2 dysfunction and Ca2+-dependent arrhythmogenesis in ARVC.

Figure 1. Left ventricular tissue from ARVC patients is characterized by integrin β1D down-regulation and RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation.

(A) Representative ECG recordings from four patients with ARVC obtained during hospitalization but before cardiac transplantation. (B) Quantification of proteins associated with intracellular calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum from protein mass spectrometry analyses. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images obtained using antiserum against integrin β1D in fixed left ventricle tissue sections from healthy donor (HD, left) or ARVC patients (right). (D) Quantification of integrin β1D Immunofluorescence intensity (n=4 per group; Each group includes 5 slides). (E) Representative immunoblots for integrin β1D, total RyR2, pRyR2 Ser-2808, pRyR2 Ser-2814, pRyR2 Ser-2030 and GAPDH protein expression in left ventricular tissue homogenates from HDs or patients with ARVC. (F) Quantification of integrin β1D immunoblots shown in (E) relative to GAPDH expression (n=4 per group). Note that both mature and precursor forms of β1D integrin subunit were reduced. (G-I) Quantification of immunoblots showing increased phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser-2030 in left ventricle tissue from patients with ARVC compared to HD tissue HD. There were no significant differences between the groups in RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2808 or Ser-2814. (n=4 per group). The data represent the means ± SEM; *P<0.05; ***P<0.001; n.s., not significant; Student’s t test. Abbreviations: ARVC, Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; HD, Healthy Donors; β1D, integrin β1D; RyR2, Ryanodine Receptor 2; BIN1, Bridging integrator 1; Cav1.2, L-type Cav1.2 calcium channel; CaM, Calmodulin; CASQ2, Calsequestrin 2; IP3R2; Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, type 2; ITGB1, Integrin beta-1; JCTN, Junctin; JP2, Junctophilin-2; NCX1, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, isoform 1; PLB, phospholamban; SERCA2a; Sarcoplasmic / endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2a; TRDN, Triadin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To investigate the function of integrin β1D and its potential interaction with RyR2 in cardiomyocytes, we first examined integrin β1D protein expression levels and the relative phosphorylation status of RyR2 in LV heart tissues from the four ARVC patients and HDs. Consistent with protein mass spectrometry data, western blot analyses further confirmed that integrin β1D expression was markedly decreased in patients with ARVC, as compared to HDs (Figures 1E–F). While the phosphorylation levels of RyR2 at S2814 and S2808 sites did not differ between patients and HDs, we did observe a hyper-phosphorylation state of RyR2 at S2030 site (Figures 1E–I). On the contrary, integrin β1D is significantly upregulated in LV hearts of ICM and HCM, as compared to HDs, respectively (Supplemental Figure 5). Interestingly, ICM and HCM hearts showed increased phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser-2808 and Ser-2814, but not at Ser-2030 site (Supplemental Figure 5). These results suggest integrin β1D downregulation is a unique phenomenon of ARVC.

Integrin β1D stabilizes RyR2 by suppressing RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030.

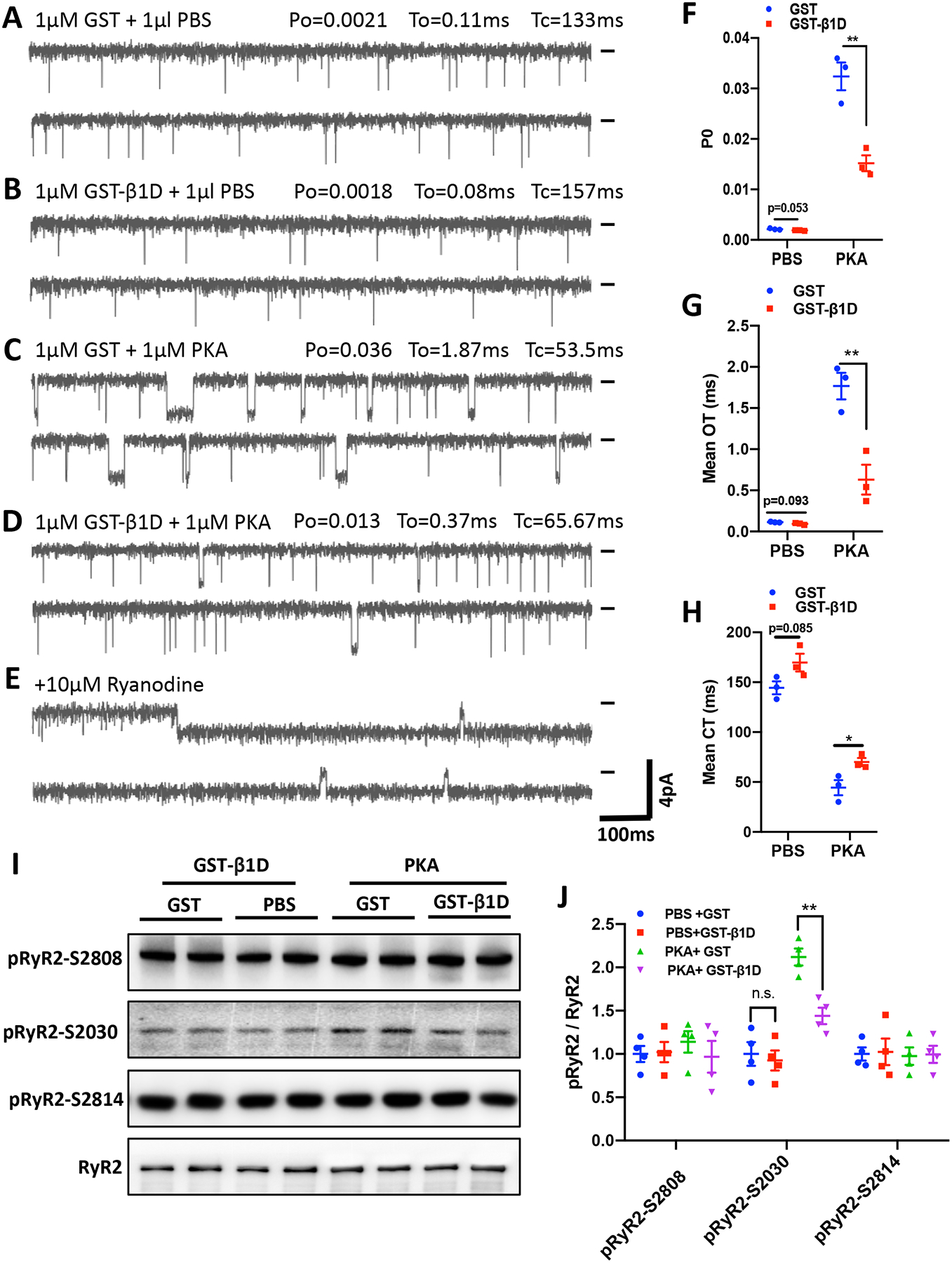

Previous studies suggest that integrin β1D stabilizes RyR2 by binding to the interdomain of RyR2, but lack of evidence for the functional implications of this interaction.29 As we found that integrin β1D protein expression is markedly and specifically down-regulated in ARVC hearts, we investigated the effect of exogenous integrin β1D on RyR2 activity by fusing SR vesicles into planar lipid bilayers. We isolated single RyR2 channels from a freshly explanted ARVC heart (Case 1) and then performed single-channel recordings before and after the addition of GST-β1D (1 μM) to the cytosolic side of the channel (Figures 2A and B). After a 30 min incubation, GST-β1D reduced RyR2 activity, which is reflected by a reduction in RyR2 open probability (Po) (0.002133±0.000096 vs. 0.001873±0.000033, P=0.053, n=3) and mean open time (To) (0.114043±0.002483 ms vs. 0.093333±0.005624 ms, P=0.093), and an increase in mean closed time (Tc) (144.467±5.284 ms vs. 169.667±7.323 ms, P=0.085) (Figures 2F–H). PKA treatment substantially increased RyR2 activity, an effect that was suppressed by GST-β1D (Po: 0.032401±0.002245 vs. 0.015177±0.001277, P<0.01; To: 1.766667±0.131852 ms vs. 0.630132 ±0.148399 ms, P<0.01; Tc: 44.376±6.244 ms vs. 70.014±3.300 ms, P<0.05, n=3) (Figures 2C–H). These findings suggest that integrin β1D directly modulates RyR2 channel activity by suppressing channel open probability and time.

Figure 2. Integrin β1D attenuates PKA-mediated RyR2 activation.

(A-E) Single channel activity of RyR2 from SR vesicles isolated from an ARVC heart (case 1). RyR2 channels were recorded in a solution containing 250 mM KCl and 25 mM Hepes (pH 7. 4) 1 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 260 nM Ca2+ (cytosolic) and 2.5 mM Ca2+ (luminal). Single RyR2-channel activity after pre-incubation with: 1 μM GST for 30 min followed by 15 min treatment with 1 μl of PBS (A), 1μM GST-β1D for 30 min followed by 15 min treatment with 1 μl of PBS (B), 1μM GST for 30 min followed by 15 min treatment with 1μM PKA (C), or 1μM GST-β1D for 30 min followed by 15 min treatment with 1μM PKA (D); or 10μM ryanodine to confirm RyR2 channel identity (E). Recording potentials, −20 mV. Zero-current baselines are indicated (short bar). (F-H) Summary data from RyR2 single channel recordings determining mean open time (To, F), open probability (Po, G) and mean closed time (CT, H). (A-H), n=3 independent experiments for each group. (I) Representative immunoblots for total RyR2, pRyR2 Ser-2808, pRyR2 Ser-2814, and pRyR2 Ser-2030 protein levels in samples with the treatments described in (A-D). (J), Quantification of pRyR2 Ser-2808, pRyR2 Ser-2814 and pRyR2 Ser-2030 phosphorylation levels normalized to total RyR2 protein expression. n = 4 independent experiments for each group. The data represent the means ± SEM; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; n. s., not significant; Student’s t test. Abbreviations: PKA, Protein kinase A; PBS, Phosphate-buffered saline; GST, glutathione S-transferase; GST-β1D, GST-tagged integrin β1D fusion protein; β1D, integrin β1D; RyR2, Ryanodine Receptor 2.

To investigate how integrin β1D stabilizes RyR2 function, we analyzed RyR2 phosphorylation levels following the same treatments described above (Figures 2A–D) by western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies. PKA treatment increased the phosphorylation level of RyR2 at Ser-2030, but not Ser-2808 or Ser-2814 (Figures 2I–J). GST-fused Integrin β1D markedly repressed PKA-induced RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030. These results suggest that integrin β1D can stabilize RyR2 function by suppressing PKA-dependent RyR2 Ser-2030 phosphorylation levels.

CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias in integrin β1D−/− mice

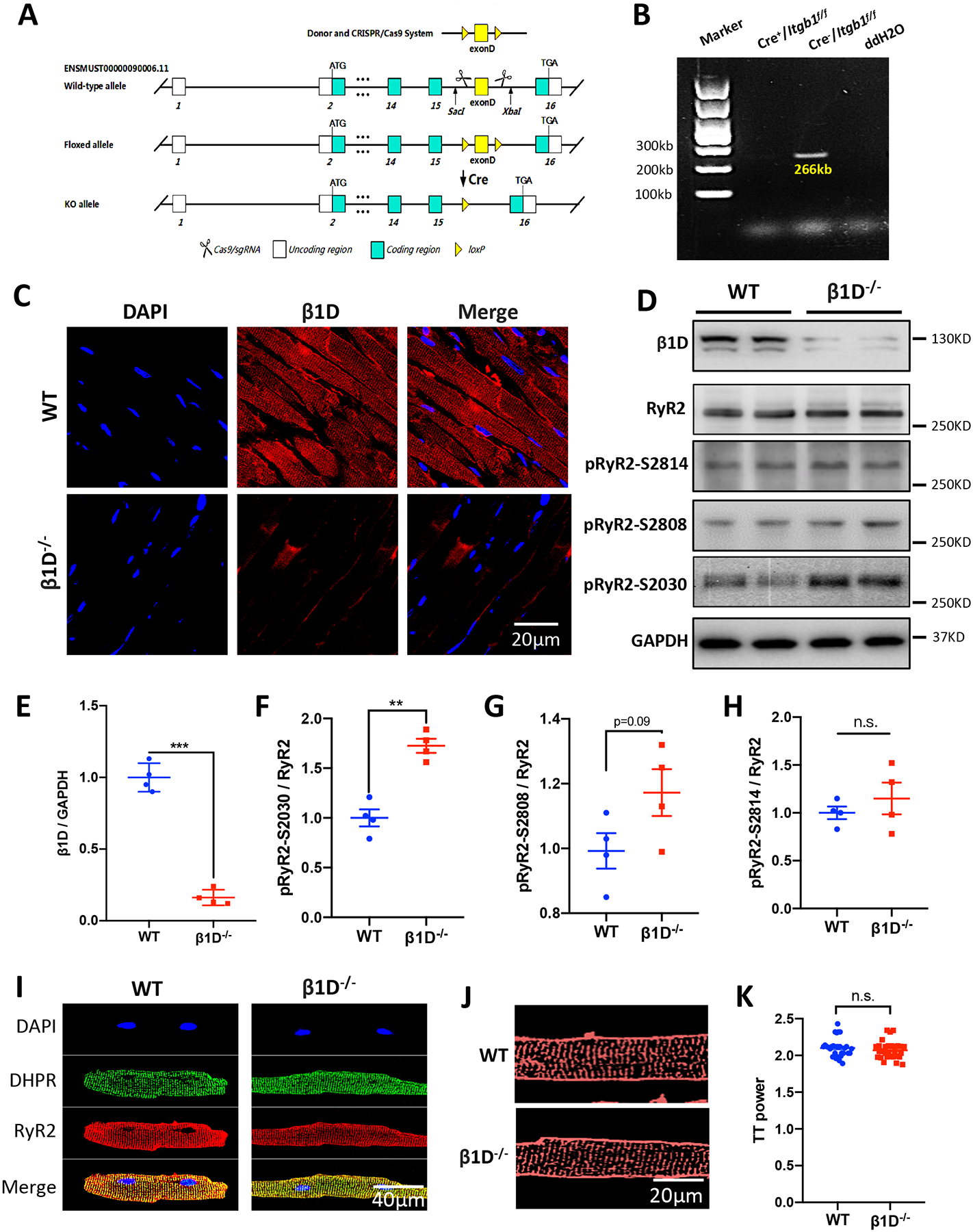

To reveal the in vivo effects of integrin β1D deficiency on cardiac function and to validate our findings from human patients, we engineered a cardiac-specific β1D−/− mouse model using the tamoxifen-inducible Cre-LoxP system (Figures 3A–B). We first confirmed the loss of integrin β1D expression in left ventricle of β1D−/− mice by immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoblotting. Integrin β1D fluorescence was significantly diminished in β1D−/− myocardium, as compared to WT control hearts (0.23±0.089 vs. 1.00 ±0.153, p<0.001, n=4) (Figure 3C). Western blotting data confirmed a 77% reduction in integrin β1D in β1D−/− hearts (Figures 3D–E and Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 3. Generation and evaluation of the β1D−/− mouse model under basal conditions.

(A) Schematic of the targeting vector and generation of β1D−/− mice. (B) RT-PCR analysis of integrin β1D mRNA in ventricle samples from WT (Cre−/Itgb1f/f) and β1D−/− (Cre+/Itgb1f/f) mice. (C) Representative immunostaining for integrin β1D and nuclei in left ventricular tissue sections from β1D−/− and WT mice (Blue, DAPI stained nuclei; Red, β1D). Heart tissues were collected from mice two weeks after the last dose of tamoxifen injection. (D) Representative immunoblots for integrin β1D, total RyR2, pRyR2 Ser-2030, pRyR2 Ser-2808, pRyR2 Ser-2814 and GAPDH protein levels in left ventricular tissue homogenates from WT and β1D−/− mice. (E-H) Quantitative assessment of the protein levels represented in (D). n=4 hearts/genotype. (I) Representative DHPR and RyR2 immunostaining of WT and β1D−/− isolated cardiomyocytes. (J) Representative Di-8-ANEPPS immunostaining of WT and β1D−/− isolated cardiomyocytes. (K) Mean TT power values, where TT power indicates the strength of the regularity of the T-tubule network. n=25–30 cells from 3 hearts/genotype. The data represent the means ± SEM; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; n. s., not significant; Student’s t test. Abbreviations: β1D, integrin β1D; β1D−/−, integrin β1D knockout; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase coupled polymerase chain reaction; DHPR, Dihydropyridine (L-type Ca2+ channel); RyR2, Ryanodine Receptor 2.

Next, we examined total and phosphorylated RyR2 levels in the left ventricle of β1D−/− mice two weeks after the last dose of tamoxifen injection. The phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser-2030 was increased by 72.5% in β1D−/− mice as compared to WT littermate controls. However, the phosphorylation levels of RyR2 at Ser-2808 and Ser-2814 did not differ between β1D−/− and WT mice (Figures 3D and 3F–H). These data are consistent with the studies performed using human ARVC samples.

Having shown that the β1D−/− mouse model replicates the molecular findings in human ARVC patient hearts, we next characterized the in vivo effects of cardiac-specific integrin β1D knockout on cardiac function two weeks after the last dose of tamoxifen injection. Compared with WT littermates, β1D−/− mice displayed no overt alterations in cardiac function in terms of echocardiographic parameters Supplemental Figure 7), histology or cardiomyocyte size (Masson and WGA staining, respectively) (Supplemental Figure 8). We also observed no differences in the distribution and expression levels of key excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling proteins or the organization of T-tubules in cardiomyocytes (Figure 3I–K, Supplemental Figure 9). Cardiac fibrosis was dramatically increased 3 months later in β1D−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 10). These data indicate that chronic integrin β1D deficiency may contribute to cardiac fibrosis in ARVC.

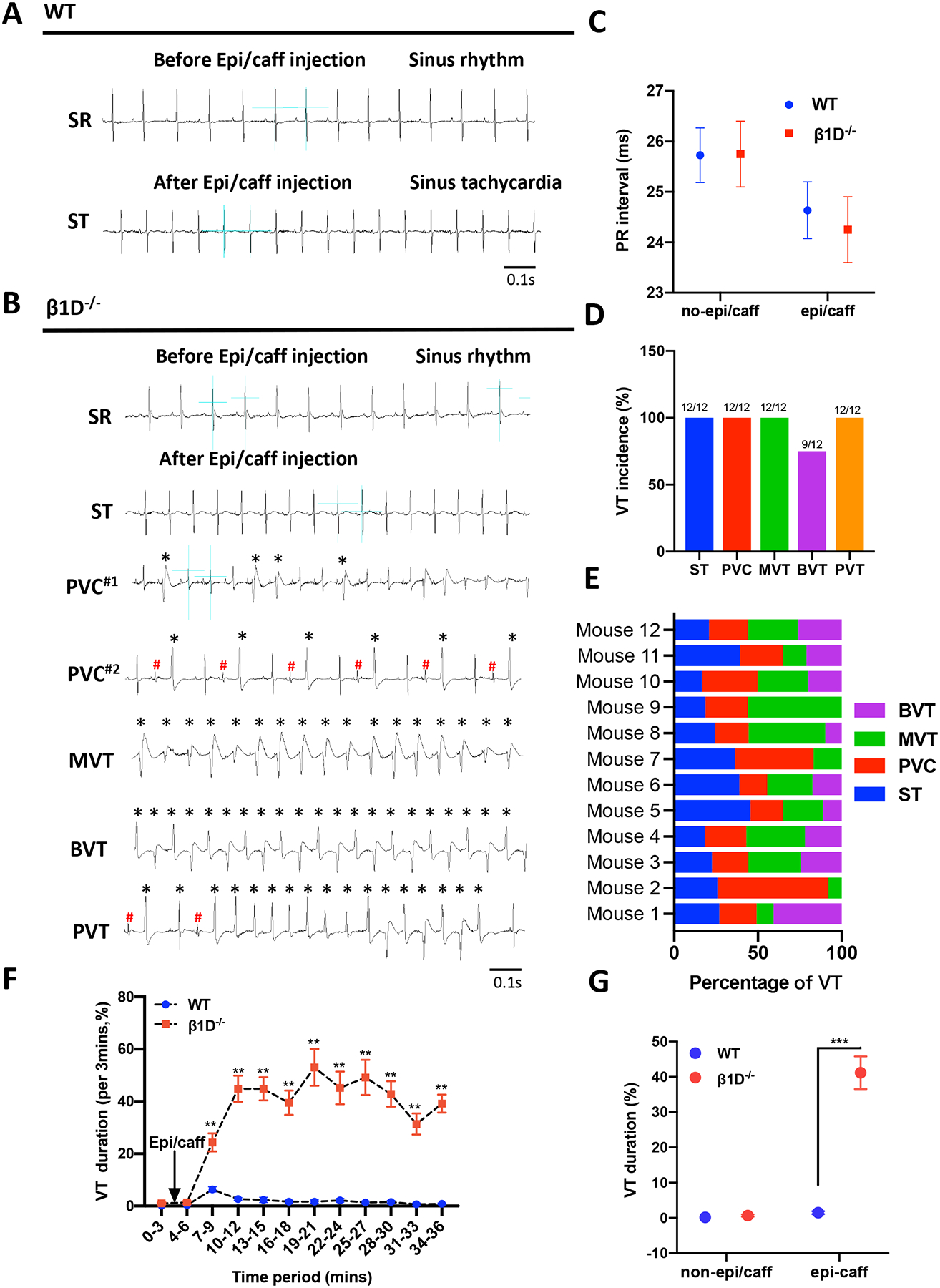

Hyperactivation of RyR2 is linked to the increased propensity for stress-induced cardiac arrhythmias such as CPVT and atrial fibrillation.13–15, 30–33 We then analyzed the electrophysiological properties of β1D−/− and WT mice under baseline conditions and cardiac stress. We found that β1D−/− mice have normal ECG recordings and regular heart rhythm at rest (Figures 4A–D, Supplemental Figure 11). However, upon sympathetic stress through administration of epinephrine (1.6 mg/kg) and caffeine (120 mg/kg), β1D−/− mice more readily developed ventricular arrhythmias than WT mice, characterized by irregular heart rates, sustained VT episodes, typical bidirectional ventricular arrhythmias and prolonged tachycardias (Figures 4B–H). These data clearly demonstrate that integrin β1D deficiency predisposes the heart to stress-induced, CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 4. β1D−/− mice develop cardiac arrhythmias in response to sympathetic stress.

(A-B) Representative ECG recordings from WT and β1D−/− mice before (A) and 3–6 min after (B) intraperitoneal injection of epi/caff. (C) PR interval from WT and β1D−/− mice before and after intraperitoneal injection of epi/caff. (D) Incidence of different types of VT (ST, PVC, MVT and BVT) calculated from β1D−/− mice in response to epi/caff. (E) Percentage of VT type occurring in individual β1D−/− mice. (F) VT occurred intermittently and the percentage (%) time in VT (VT duration) was measured within each of 10 consecutive 3-min periods immediately after epi/caff injection. (G) VT duration over the entire 30-min recording period. The data represent the means ± SEM for WT (n=11) and β1D−/− (n=12) mice; Student t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. WT. Abbreviations: ECG=electrocardiogram; WT, Cre−/Itgb1f/f mice; β1D−/−, integrin β1D knockout; epi/caff= epinephrine (1.6mg/kg) and caffeine (120mg/kg). VT= Ventricular tachycardia; ST= Sinus tachycardia; PVC= Premature ventricular contraction; MVT= Monomorphic broad complex VT; BVT= Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia; PVT= Polymorphic VT. * / # = Different morphology of PVCs.

β1D−/− cardiomyocytes exhibit RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation, delayed afterdepolarizations and spontaneous Ca2+ release under β-adrenergic stimulation.

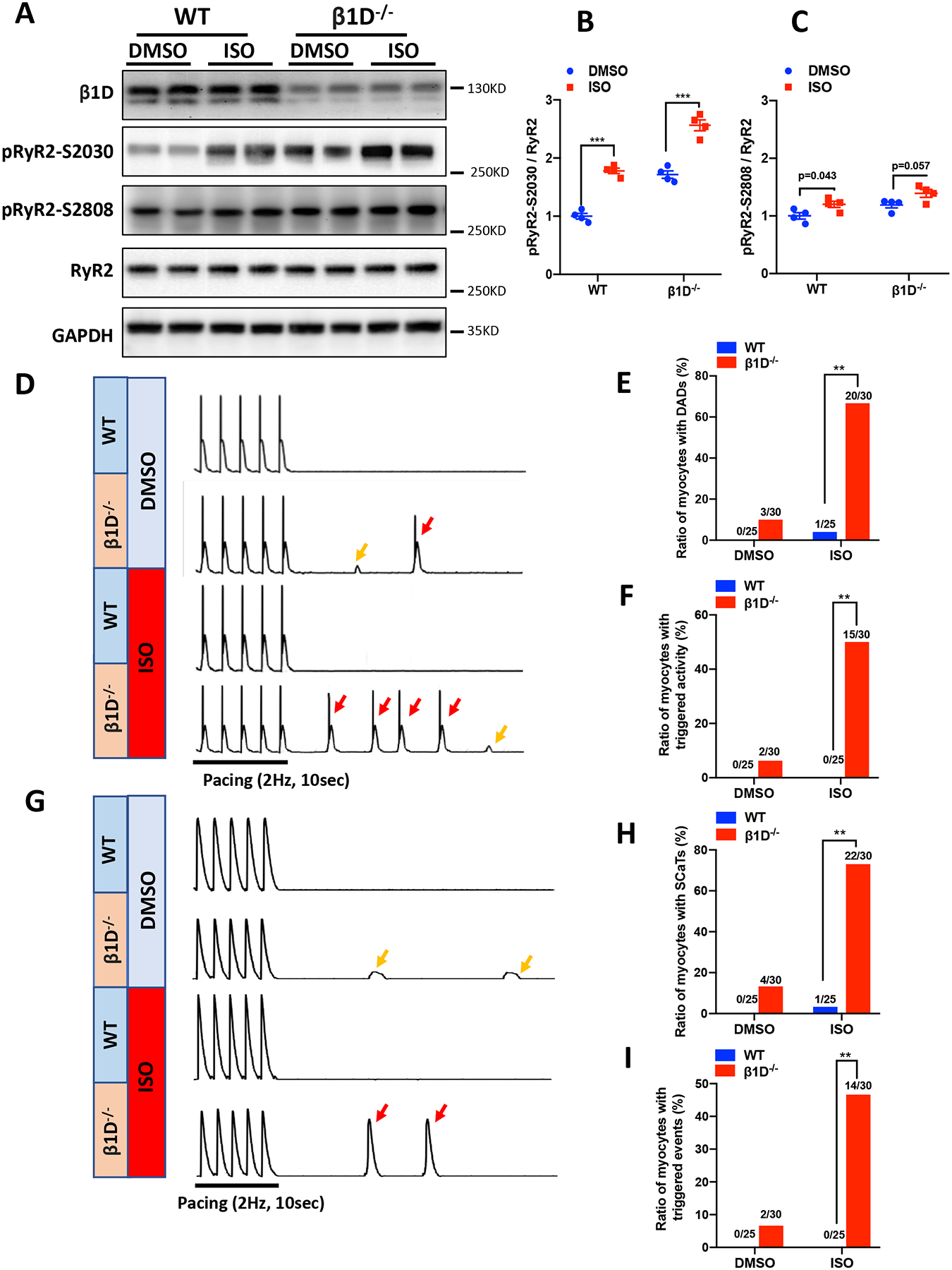

Given that the β1D−/− mice exhibited CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias under stress, we next tested if there is any change in RyR2 Ser-2030 and Ser-2808 phosphorylation levels in hearts from WT and β1D−/− mice under β-adrenergic stimulation. In addition to an increase in basal Ser-2030 phosphorylation (by 72%, Figure 5A–B), we found that ISO markedly increased RyR2 phosphorylation levels at Ser-2030 in both strains (by 78±7%, WT vs. by 49±11%, β1D−/−, p<0.001). In contrast, β1D deficiency only results into a small trend toward an increase in Ser-2808 phosphorylation level at baseline (by 19% compared to WT). ISO stimulation also induced no more than a 20% increase in Ser-2808 phosphorylation (20±8%, WT, p=0.043 vs. 16±9%, β1D−/−, p=0.057) (Figures 5A–C). In addition, using anti-phospho antibodies against Ser-2808 from different sources, we found similar moderate increases in RyR2 phosphorylation levels in WT hearts in response to ISO (Supplemental Figure 12). These results indicate that integrin β1D regulates RyR2 phosphorylation primarily on Ser-2030, and RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation may be responsible for adrenergic stimulation-induced VT.

Figure 5. Integrin β1D deficiency induces RyR2 Ser-2030, but not Ser-2808 hyper-phosphorylation and promotes stress-induced DAD and spontaneous Ca2+ release.

(A-C) RyR2 Ser-2030 and Ser-2808 phosphorylation levels at baseline or in response to ISO stimulation (100nM perfusion for 30 min) in WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative immunoblots of RyR2 Ser-2030 and Ser-2808 phosphorylation levels. (A-B) The mean ratios of RyR2 phosphorylated at Ser-2030 (B) and Ser-2808 (C) to total RyR2 protein levels at baseline or under ISO treatment. n=4 hearts for each group. Data represent means ± SEM; ***P<0.001; Student’s t test. (D) Representative traces of action potentials in WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes ±100nM ISO. Small DADs (yellows arrows) and triggered activities (red arrows) were recorded after a pause following 2-Hz field stimulation. (E-F) Cumulative incidence of DADs (E) and triggered activities (F) in WT and β1D−/− mice (n=25–30 cells per group from four hearts/genotype). (G) Representative traces showing SCaTs (yellow arrows) and triggered beats (red arrows) after a pause following 2-Hz field stimulation in WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes ±100nM ISO. (H-I) Cumulative incidence of SCaTs (H) and triggered beats (I) in WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes (n=25–30 cells per group from 4 hearts/genotype). **P<0.01; χ2 test. Abbreviations: DADs, delayed afterdepolarizations; SCaTs, spontaneous Ca2+ transients.

To investigate the role of integrin β1D on myocyte electrophysiological properties, we recorded action potentials (APs) from WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes in the absence or presence of 100 nM ISO during and after pacing stimulation. In the absence of ISO, spontaneous DADs were not found in WT but were present in 10% (3/30) of β1D−/− cells. In the presence of ISO, 4% (1/25) WT cardiomyocytes showed spontaneous DADs which increased to 66.67% (20/30) in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes (P<0.01) (Figures 5D–E). Moreover, triggered activities were not observed in WT cardiomyocytes but occurred in 50% (15/30) of β1D−/− cardiomyocytes (p<0.01) in the presence of ISO (Figure 5F).

It is well accepted that diastolic spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR underlies DAD and triggered activity.34 To determine the contribution of RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ release in the increased arrhythmogenesis we saw in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes, we measured the occurrence of spontaneous Ca2+ transients (SCaTs) after halting regular pacing (2 Hz) in Fluo-4AM–loaded cardiomyocytes. In the absence of ISO stimulation, 13% (4/30) of β1D−/− cells exhibited SCaTs, while all WT cells remained quiescent after suspension of pacing. In the presence of ISO, however, 73% (22/30) of the β1D−/− cardiomyocytes developed SCaTs compared with only 4% (1/25) of the WT cardiomyocytes (P<0.05) (Figures 5G–H). Moreover, 47% (14/30) of the β1D−/− cells but no WT cells developed triggered events (P<0.01) (Figures 5G and I). To test whether spontaneous SR Ca2+ release underlies the abnormal electric activities, we pretreated β1D−/− cardiomyocytes with ryanodine (1 μM). Here, ryanodine significantly inhibited spontaneous Ca2+ waves and, subsequently, DADs and triggered activities in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes under ISO stimulation (Supplemental Figure 13). Taken together, these data suggest that β1D−/− cardiomyocytes are more susceptible to Ca2+-dependent arrhythmogenesis due most likely to abnormal Ca2+ handing caused by RyR2 hyperphosphorylation.

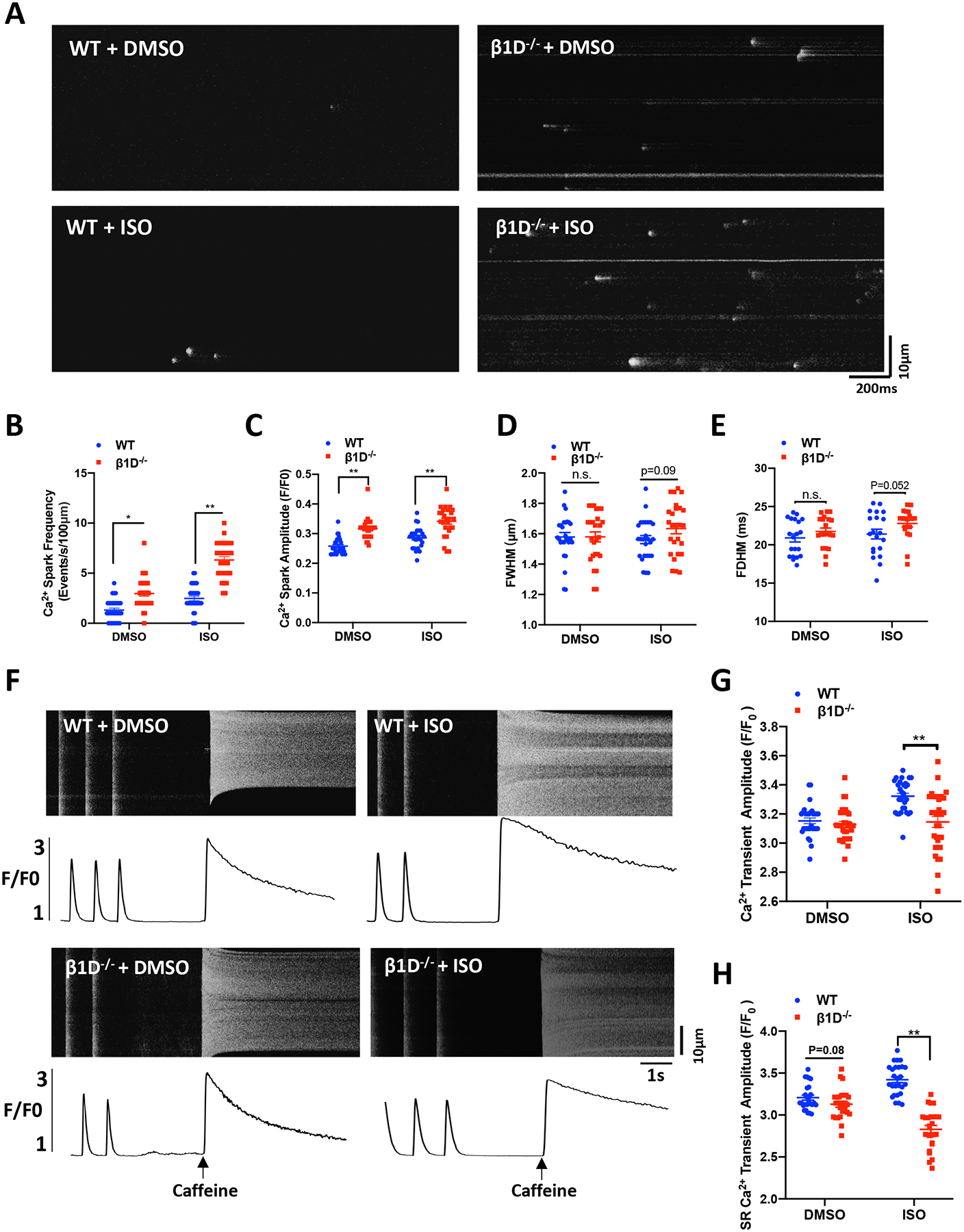

Enhanced Ca2+ spark activities and reduced SR Ca2+ levels in β1D deficient cardiomyocytes

Ca2+ sparks are elementary Ca2+ release events mediated by Ca2+ efflux through RyR2s, in cardiomyocytes, representing the gating properties of RyR2s.35 We measured Ca2+ sparks in quiescent Fluo-4–loaded cardiomyocytes. We found that the frequency of Ca2+ sparks was significantly increased in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes compared to WT cardiomyocytes at baseline (0.98±0.064 vs. 2.45±0.472, P<0.05). In the presence of ISO, Ca2+ spark frequency was further increased (2.23±0.054 vs. 5.96±0.39, P<0.01) (Figures 6A–B). Ca2+ spark amplitude showed the same trend as the Ca2+ spark frequency (Figure 6C). The full width or full duration at half-maximum (FWHM or FDHM) and was unchanged in β1D−/− cardiomyocytes (Figure 6D). In addition, we assessed SR Ca2+ content by measuring caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients after cessation of pacing followed by rapid application of caffeine (10 mM, Figures 6F–H). We found that β1D−/− cardiomyocytes showed significantly lower SR Ca2+ levels than WT cardiomyocytes (3.43 ±0.013 vs. 2.78±0.025, P<0.01) in the presence of ISO. Collectively, these data implicate that β1D deficiency leads to altered RyR2 function consistent with the biochemical evidence aforementioned, i.e., hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser-2030.

Figure 6. β1D−/− cardiomyocytes display increased Ca2+ spark frequency and reduced SR Ca2+ content.

(A) Representative Ca2+ spark images in myocytes from WT and β1D−/− mice at baseline or under 100nM ISO treatment. (B) Mean frequency of Ca2+ sparks. (C) Mean amplitude of Ca2+ sparks. (D) Mean full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the Ca2+ sparks. (E) Mean duration at half-peak amplitude (FDHM) of Ca2+ sparks. n=20–30 cells from 4 hearts/genotype per group. (F-H) SR content was measured by measuring caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. (F) Representative traces of 1-Hz field stimulation-triggered Ca2+ transients and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (SR content) from WT and β1D−/− cardiomyocytes with or without 100nM ISO treatment. (G) Average data of the amplitude of Ca2+ transients. (H) Cumulative data on the amplitudes of caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ release (i.e., SR Ca2+ content). n= 20–30 cells from 4 hearts/genotype for each group; The data represent the means ± SEM; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; n.s., not significant; Student’s t test.

DSP deficiency leads to elevated ubiquitination and degradation of integrin β1D through an ERK1/2 – Fibronectin pathway

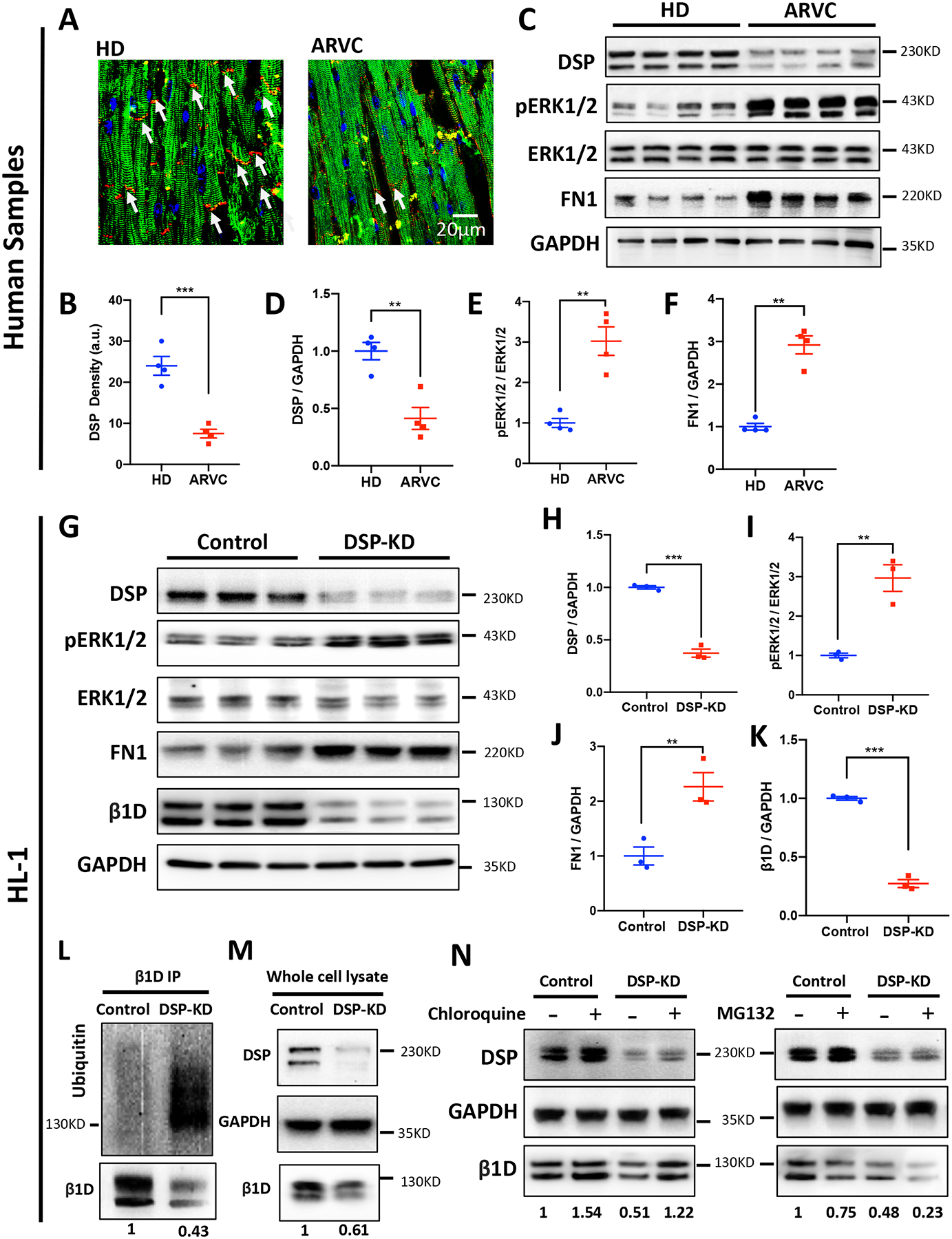

Loss of desmosomal proteins is considered a molecular hallmark of ARVC.9 We identified severe downregulation of desmoplakin (DSP) in human ARVC tissues by immunostaining (Figure 7A & B), western blots (Figures 7C & D, 1.00 ±0.09 vs. 0.41±0.11, P<0.01) and protein mass spectrometry analyses (Supplemental Table 4). It has been suggested that DSP loss triggers robust activation of ERK1/2 in cardiomyocytes.36 Hyperactivation of ERK1/2 may boost the expression of fibronectin 1 (FN1),37 an extracellular matrix ligand of integrin β1, which promotes integrin β1 ubiquitination and degradation.38 Indeed, our protein mass spectrometry analyses also showed FN1 is significantly upregulated in ARVC patient hearts (Supplemental Table 4). Our western blotting analyses demonstrate 3-fold higher levels in FN1 and active phospho/total ERK1/2 ratios in ARVC heart samples, compared to those of healthy donors (Figures 7C, E–F & Supplemental Figure 14). We postulated that down-regulation of integrin β1D may result from a pathological ERK1/2-dependent fibronectin induction pathway in ARVC cardiomyocytes. To investigate whether DSP loss is responsible for ERK1/2 activation and fibronectin elevation, we used DSP siRNA to specifically knock down DSP in HL-1 cells and then quantified the expression levels of candidate downstream proteins. Consistent with our hypothesis, DSP knockdown (KD, by ~70%) resulted into a marked increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, FN1 protein expression and degradation of integrin β1D protein (Figures 7G–K) comparable to that in ARVC hearts. Furthermore, treatment with an ERK specific inhibitor (FR180204) or knockdown of FN1 prevented β1D degradation in DSP-KD HL-1 cells (Supplemental Figure 15 & 16). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed that integrin β1D transcript levels are similar between ARVC and HD hearts and between control and DSP-KD HL-1 cells, suggesting that DSP-dependent regulation of integrin β1D expression is not related to changes at the transcript level Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 7. Downregulation of DSP promotes ubiquitination and degradation of integrin β1D.

(A) Representative immunofluorescent images of DSP in HD and ARVC heart sections (Blue, nucleus; Red, DSP; Green, actin). (B) Image quantification showing significantly lower DSP in patients with ARVC compared to HD (n=4 per group; 5 slides for each group; **p<0.05, Student’s t-test). (C) Representative immunoblots for DSP, ERK1/2, pERK1/2, FN1, integrin β1D and GAPDH protein expression in left ventricle tissue homogenates from HDs and patients with ARVC (n = 4 per group). (D-F) Quantification of immunoblots shown in (B) demonstrating reduced DSP protein, increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and FN1 in left ventricle tissues from patients with ARVC than in tissues from HD. (G) Representative immunoblots for DSP, ERK1/2, pERK1/2, FN1, integrin β1D and GAPDH protein expression in the control and DSP-knockdown (DSP-KD) HL-1 cells (n=3). (H-K) Quantification of immunoblots of DSP, pERK1/2 / ERK1/2, FN1, and integrin β1D protein expression in the control and DSP-KD HL-1 cells. (L) integrin β1D was immunoprecipitated from control and DSP-KD HL-1 cells. Samples were subsequently blotted for integrin β1D and ubiquitin. (M) Whole cell lysate immunoblots from samples used for immunoprecipitation in (L) (n=4). (N) The lysosomal inhibitor Chloroquine was able to restore β1D expression levels in response to DSP-KD in HL cells (left). MG132, a potent proteasome inhibitor, was used to assess role of proteasomal degradation of β1D caused by DSP loss in HL-1 cells (right) (n = 3 independent experiments, respectively). The data represent means ± SEM; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; n. s., not significant; Student’s t test. Abbreviations: DSP, Desmoplakin; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2; FN1, Fibronectin1; DSP-KD, Desmoplakin knockdown; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To determine whether integrin β1D is ubiquitinated in response to DSP loss, immunoprecipitates of endogenous integrin β1D from control and DSP-KD HL-1 cells were immunoblotted for endogenous ubiquitin. Using the mono/polyubiquitin antibody FK2, it was observed that integrin β1D was ubiquitinated at a much higher level in DSP-KD samples compared with control group (Figures 7L–M). Further experiments demonstrated that inhibition of lysosomal degradation (with chloroquine), but not inhibition of proteasome function (with MG132) protects against DSP-KD induced Integrin β1D downregulation (Figure 7N). These data suggest that integrin β1D is not directly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system but targeted by ubiquitin for degradation in the lysosome.

DISCUSSION

ARVC is an inherited desmosomal cardiomyopathy characterized by a high burden of ventricular arrhythmias and increased risk for SCD.8, 9 Ventricular arrhythmias in ARVC are often related to exercise or emotional excitement, suggesting that they are sensitive to catecholamines.22, 23, 39 Indeed, clinical studies have shown a high inducibility of polymorphic premature ventricular contractions or ventricular tachycardia during isoproterenol infusion testing in ARVC patients.22, 23 However, the arrhythmogenic mechanism of ARVC remains elusive. Here, in the present study, we reveal for the first time a critical role of integrin β1D-mediated Ca2+ signaling in the arrhythmogenesis of ARVC.

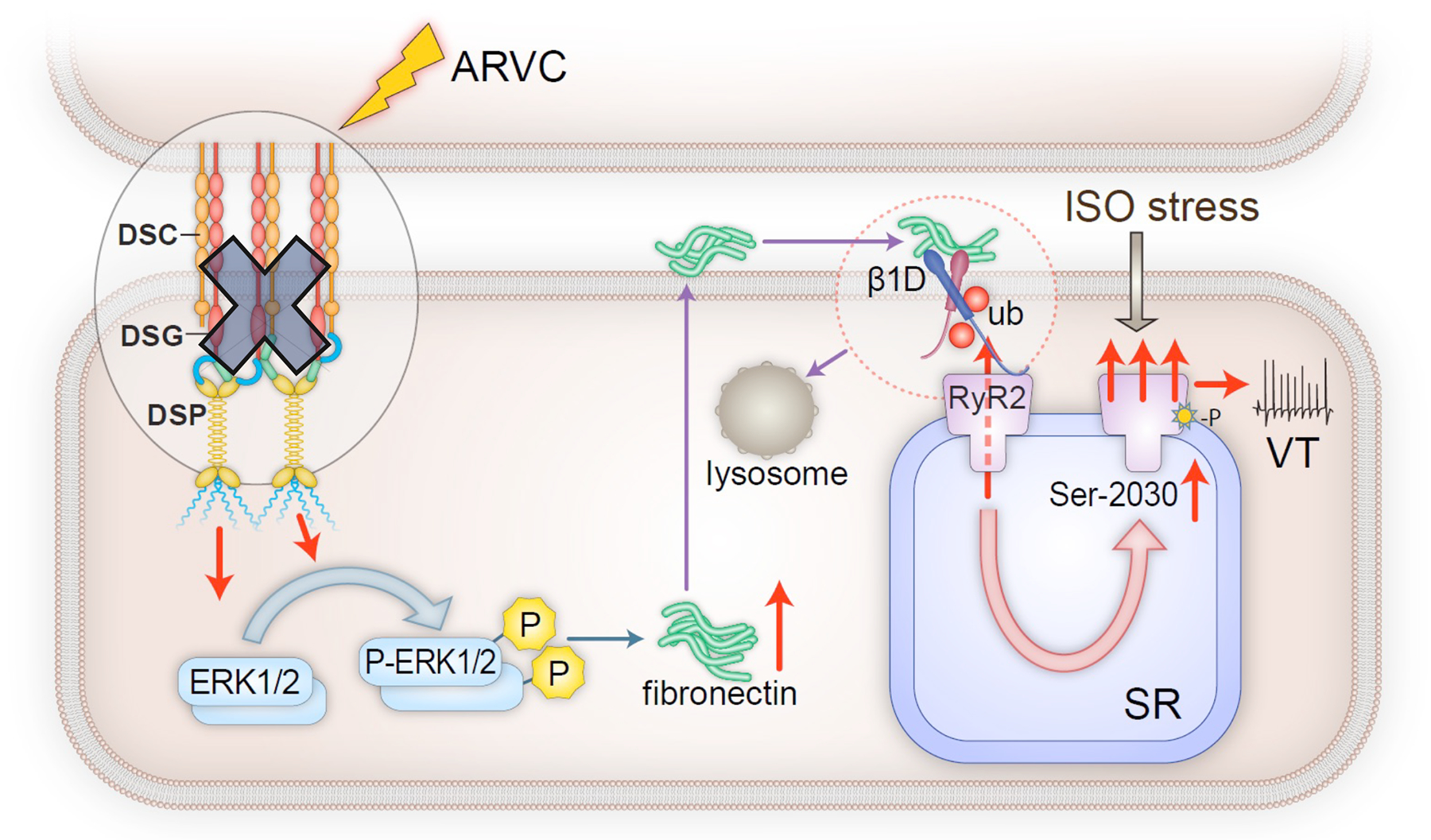

In this study, using non-biased protein mass spectrometry, we first identified that integrin β1D protein is significantly downregulated in ARVC patient heart tissue in parallel with reduction of desmosomal proteins such as DSP, DSC2 and DSG2. On the contrary, integrin β1D is upregulated in human ICM and HCM, suggesting that integrin β1D downregulation is a unique change in ARVC. Functionally, integrin β1D is linked to RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030. We observed RyR2 hyper-phosphorylation at Ser-2030 in ARVC, but not in ICM or HCM heart samples. Exogenous integrin β1D decreases PKA-induced RyR2 Ser-2030 phosphorylation and RyR2 channel open probability in samples isolated from hearts with ARVC. These results indicate that integrin β1D stabilizes RyR2 via its influence on Ser-2030 phosphorylation. Importantly, we validated the in vivo function of integrin β1D in cardiomyocytes using a cardiac inducible integrin β1D specific knockout mouse model. We demonstrated that integrin β1D deletion in mice for only two weeks, a time point preceding overt structural and functional phenotypes, results in CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias, RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation, SR Ca2+ leak, DADs and triggered activities under isoproterenol stress. Lastly, we revealed that loss of desmoplakin causes integrin β1D deficiency in ARVC, which is mediated through an ERK1/2 - fibronectin - ubiquitin/lysosome pathway. Taken together, our study supports an important role for integrin β1D deficiency and subsequent RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation on mediating catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia in patients with ARVC.

Integrin β1D deficiency is a unique molecular change observed in ARVC, which is not seen in other forms of human heart diseases including ischemic cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. More interestingly, integrin β1D is consistently downregulated among patients with distinct ARVC mutations, suggesting that integrin β1D deficiency is a common consequence of ARVC, independent of heritable causation. ARVC is characterized by intercalated disk remodeling and loss of desmosomes.40 Loss of desmosomal proteins is considered a molecular hallmark of ARVC. We did observe significant downregulation of multiple desmosomal proteins in human ARVC. This is confirmed by our data from protein mass spectrometry analyses. DSP knockdown in HL-1 cells triggered the robust activation of ERK1/2 and supports previous findings in neonatal rat ventricular myoyctes.36 Furthermore, we were surprised to find ERK1/2 activation in DSP deficient cells is required for the induction of fibronectin 1 and subsequent loss of integrin β1D through ubiquitination and lysosome-mediated degradation. These mechanistic studies are sufficient to explain how defects in desmosome function in ARVC patients produce similar reductions in integrin β1D levels (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Schematic to illustrate the proposed mechanism of catecholamine-sensitive VT in ARVC.

ARVC from loss of function mutations in desmosomal genes results in robust increase in pERK1/2 and the induction of fibronectin expression. Subsequent fibronectin secretion leads to the ubiquitination and degradation of integrin β1D. Decreased integrin β1D increases Ser-2030 phosphorylation on RyR2 and impairs RyR2 stability, thereby causing enhanced Ca2+ leak that promotes VT under ISO stress.

Previous studies have shown that in addition to localizing to intercalated discs, integrin β1D also distributes to T-tubule regions of cardiomyocytes,25, 26 where it regulates RyR2 phosphorylation levels at Ser-2808.29 However, our combined results from ARVC heart tissue, isolated ARVC patient cardiomyocytes and our β1D knockout mouse model strongly suggests that the level of integrin β1D is linked to the status of RyR2 phosphorylation, particularly at Ser-2030, rather than at Ser-2808 or Ser-2814 sites (See Figures 1E–I, 2I–J, 3D–H, 5A–C). RyR2 phosphorylation is complex, and has been a controversial topic, especially regarding its role in mediating heart failure development.41–46 Our results showing integrin β1D antagonizes PKA-induced RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030 (Figures 2I & 5A) are consistent with previous observations from Wayne Chen’s group who reported that Ser-2030 is the major PKA site responding to β-adrenergic stimulation.47 Our data also demonstrate that when integrin β1D expression level is reduced, β-adrenergic stimulation induces stronger RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030 (Figure 5A–C), leading to aberrant SR Ca2+ activity and Ca2+-dependent arrhythmias. Taken together, we conclude that loss of integrin β1D results into exaggerated RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser-2030, thereby enhancing propensity to catecholamines-sensitive ventricular tachycardia in both mice and ARVC patients. On the other hand, we observed increased expression level of integrin β1D in ICM and HCM. We postulate that upregulation of integrin β1D may provide a protective mechanism prohibiting the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in these diseases.

The contribution of dysfunctional Ca2+ handling to the arrhythmogenic mechanism of ARVC has begun to be appreciated.24, 48 Recent studies in PKP2 knockout mice from the Delmar group reported that loss of PKP2 leads to reduced expression of a group of proteins related to Ca2+ handling, i.e., RyR2, Ankyrin-B, Cav1.2 Ca2+ channel, triadin and calsequestrin-2. These factors together contribute to intracellular Ca2+ dysregulation and therefore the Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia phenotype in this mouse model.24, 48 However, our protein mass spectrometry analyses failed to identify any significant changes in these Ca2+ handling proteins in human ARVC (Figure 1B). Thus, whether findings from this study can be translated to human ARVC remains for to be investigated.

Our study has significant implications for current clinical practice. Although it is generally agreed that ARVC and CPVT are caused by mutations of different sets of genes involved in different functions at molecular and cellular levels in cardiomyocytes, we now recognize that there is some degree of convergence between ARVC and CPVT. This indeed has raised the question how clinicians and invasive electrophysiologists are to be informed on differential diagnoses of the two diseases. This is particularly more critical and difficult at the early stage of the disease when no structural findings are present in patients. In addition to medical history, treadmill test, electrophysiological examination with isoproterenol infusion, genetic test, careful examinations of cardiac MRI may provide valuable information in detecting subtle early changes in cardiac structure. For patient management, a beta blocker is strongly recommended as long as patients have CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias. Our previous study has suggested that carvedilol is the only beta blocker with the additional benefit of suppressing RyR2 activities,49 which may provide better outcomes than other beta blockers in the treatment of ARVC.

At present, there is still no effective treatment for ARVC, except for cardiac transplantation, due to a lack of mechanistic understanding of the ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in ARVC.50 Here, we identify a novel pathway that integrin β1D deficiency mediates RyR2 dysfunction and contributes to catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia in ARVC. Interventions targeting the signaling pathway that leads to integrin β1D degradation or stabilizing RyR2 function could be promising approaches for preventing ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in ARVC patients.

In summary, we identified downregulation of integrin β1D is a novel cause of catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia in ARVC. Our data implicate integrin β1D deficiency as a mechanism leading to hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser-2030, aberrant Ca2+ handling, DAD and triggered ventricular arrhythmia in ARVC, particularly under sympathetic stress. Taken together, these findings provide novel insights into the role of integrin β1D deficiency in the pathogenesis of cardiac arrhythmias in ARVC, which may have important implications for future development of new therapeutic strategies to ameliorate this condition.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What Is New?

We identify that integrin β1D is uniquely downregulated in ARVC, but not in HCM or ICM.

Exogenous integrin β1D decreases PKA-induced RyR2 Ser-2030 phosphorylation and stabilizes RyR2 channels in samples isolated from hearts with ARVC.

Integrin β1D deletion in mice results in CPVT-like ventricular arrhythmias, RyR2 Ser-2030 hyper-phosphorylation, SR Ca2+ leak, DADs and triggered activities under isoproterenol stress.

We reveal that loss of desmoplakin mechanistically contributes to integrin β1D deficiency in ARVC, which is mediated through an ERK1/2 - fibronectin - ubiquitin/lysosome pathway.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our study indicates that loss of integrin β1D may be responsible for ventricular arrhythmias in ARVC disease.

Interventions that stabilize integrin β1D levels through inhibition of its signal-specific degradation or by integrin β1D overexpression could reduce ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in ARVC patients.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Denice Hodgson-Zingman for expert comments on mouse ECG data and thank Teresa Ruggle (University of Iowa) for help on artwork.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by China Key International Cooperation Projects of National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 81620108015 (S.H.Z.); Research on the Application of Clinical Characteristics in Capital Beijing Z61100000516110 (S.H.Z); China Key projects of National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 81930044 (S.H.Z); National Heart Lung Blood Institute HL090905, HL130346, Department of Veterans Affairs of the United States I01-BX002334 (L.S.S.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- ARVC

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- Bin1

Amphyphisin-2

- BVT

Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia

- CaM

Calmodulin

- CaV1.2

L-type Ca2+ channel

- CPVT

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- CSAQ2

Calsequestrin

- CX43

Connexin-43

- DADs

Delayed afterdepolarizations

- DHPR

Dihydropyridine

- DSC2

Desmocollin 2

- DSG2

Desmoglein 2

- DSP-KD

Desmoplakin knockdown

- DSP

Desmoplakin

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ERK1/2

Extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1 and 2

- FN1

Fibronectin1

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GST-β1D

GST-tagged integrin β1D fusion protein

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- HD

Healthy donor

- ICM

Ischemic cardiomyopathy

- IP3R

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- ISO

Isoproterenol

- JCTN

Junctin

- JP2

Junctophilin-2

- MVT

Monomorphic broad complex VT

- NCX

Sodium-calcium exchanger

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PKP2

Plakophilin 2

- PLB

Phospholamban

- PVC

Premature ventricular contraction

- PVT

Polymorphic VT

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase coupled polymerase chain reaction

- RyR2

Ryanodine Receptor 2

- SCaTs

Spontaneous Ca2+ transients

- SCD

Sudden cardiac death

- SERCA2a

SR Ca2+-ATPase

- SR

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

- ST

Sinus tachycardia

- TRDN

Triadin

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

- β1D−/−

Cardiac specific β1D knockout

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Philips B and Cheng A. 2015 update on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabib A, Loire R, Chalabreysse L, Meyronnet D, Miras A, Malicier D, Thivolet F, Chevalier P and Bouvagnet P. Circumstances of death and gross and microscopic observations in a series of 200 cases of sudden death associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and/or dysplasia. Circulation. 2003;108:3000–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles C, Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Gray B, Westaby J, Ensam B, Basu J, Parry-Williams G, Papatheodorou E, Paterson C, Malhotra A, Robertus JL, Ware JS, Cook SA, Asimaki A, Witney A, Ster IC, Tome M, Sharma S, Behr ER and Sheppard MN. Sudden Death and Left Ventricular Involvement in Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2019;139:1786–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tester DJ, Ackerman JP, Giudicessi JR, Ackerman NC, Cerrone M, Delmar M and Ackerman MJ. Plakophilin-2 Truncation Variants in Patients Clinically Diagnosed With Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Decedents With Exercise-Associated Autopsy Negative Sudden Unexplained Death in the Young. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furlanello F, Bertoldi A, Dallago M, Furlanello C, Fernando F, Inama G, Pappone C and Chierchia S. Cardiac arrest and sudden death in competitive athletes with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidbuchel H, Hoogsteen J, Fagard R, Vanhees L, Ector H, Willems R and Van Lierde J. High prevalence of right ventricular involvement in endurance athletes with ventricular arrhythmias. Role of an electrophysiologic study in risk stratification. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1473–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groeneweg JA, Bhonsale A, James CA, te Riele AS, Dooijes D, Tichnell C, Murray B, Wiesfeld AC, Sawant AC, Kassamali B, Atsma DE, Volders PG, de Groot NM, de Boer K, Zimmerman SL, Kamel IR, van der Heijden JF, Russell SD, Jan Cramer M, Tedford RJ, Doevendans PA, van Veen TA, Tandri H, Wilde AA, Judge DP, van Tintelen JP, Hauer RN and Calkins H. Clinical Presentation, Long-Term Follow-Up, and Outcomes of 1001 Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Patients and Family Members. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delmar M and McKenna WJ. The cardiac desmosome and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies: from gene to disease. Circ Res. 2010;107:700–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrado D, Link MS and Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1489–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moncayo-Arlandi J and Brugada R. Unmasking the molecular link between arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy and Brugada syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:744–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrado D, Basso C and Judge DP. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2017;121:784–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I, Grau F, Ngoc DD and Coumel P. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation. 1995;91:1512–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priori SG and Chen SR. Inherited dysfunction of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis. Circ Res. 2011;108:871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song L, Alcalai R, Arad M, Wolf CM, Toka O, Conner DA, Berul CI, Eldar M, Seidman CE and Seidman JG. Calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) mutations increase expression of calreticulin and ryanodine receptors, causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizzi N, Liu N, Napolitano C, Nori A, Turcato F, Colombi B, Bicciato S, Arcelli D, Spedito A, Scelsi M, Villani L, Esposito G, Boncompagni S, Protasi F, Volpe P and Priori SG. Unexpected structural and functional consequences of the R33Q homozygous mutation in cardiac calsequestrin: a complex arrhythmogenic cascade in a knock in mouse model. Circ Res. 2008;103:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyegaard M, Overgaard MT, Sondergaard MT, Vranas M, Behr ER, Hildebrandt LL, Lund J, Hedley PL, Camm AJ, Wettrell G, Fosdal I, Christiansen M and Borglum AD. Mutations in calmodulin cause ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:703–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang HS, Nitu FR, Yang Y, Walweel K, Pereira L, Johnson CN, Faggioni M, Chazin WJ, Laver D, George AL Jr., Cornea RL, Bers DM and Knollmann BC. Divergent regulation of ryanodine receptor 2 calcium release channels by arrhythmogenic human calmodulin missense mutants. Circ Res. 2014;114:1114–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roux-Buisson N, Cacheux M, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Fauconnier J, Brocard J, Denjoy I, Durand P, Guicheney P, Kyndt F, Leenhardt A, Le Marec H, Lucet V, Mabo P, Probst V, Monnier N, Ray PF, Santoni E, Tremeaux P, Lacampagne A, Faure J, Lunardi J and Marty I. Absence of triadin, a protein of the calcium release complex, is responsible for cardiac arrhythmia with sudden death in human. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2759–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B, Guo A, Gao Z, Wei S, Xie YP, Chen SR, Anderson ME and Song LS. In situ confocal imaging in intact heart reveals stress-induced Ca(2+) release variability in a murine catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia model of type 2 ryanodine receptor(R4496C+/−) mutation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roux-Buisson N, Gandjbakhch E, Donal E, Probst V, Deharo JC, Chevalier P, Klug D, Mansencal N, Delacretaz E, Cosnay P, Scanu P, Extramiana F, Keller D, Hidden-Lucet F, Trapani J, Fouret P, Frank R, Fressart V, Faure J, Lunardi J and Charron P. Prevalence and significance of rare RYR2 variants in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: results of a systematic screening. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1999–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel H, Shah P, Rampal U, Shamoon F and Tiyyagura S. Arrythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) and cathecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT): A phenotypic spectrum seen in same patient. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48:874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denis A, Sacher F, Derval N, Lim HS, Cochet H, Shah AJ, Daly M, Pillois X, Ramoul K, Komatsu Y, Zemmoura A, Amraoui S, Ritter P, Ploux S, Bordachar P, Hocini M, Jais P and Haissaguerre M. Diagnostic value of isoproterenol testing in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philips B, Madhavan S, James C, Tichnell C, Murray B, Needleman M, Bhonsale A, Nazarian S, Laurita KR, Calkins H and Tandri H. High prevalence of catecholamine-facilitated focal ventricular tachycardia in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerrone M, Montnach J, Lin X, Zhao YT, Zhang M, Agullo-Pascual E, Leo-Macias A, Alvarado FJ, Dolgalev I, Karathanos TV, Malkani K, Van Opbergen CJM, van Bavel JJA, Yang HQ, Vasquez C, Tester D, Fowler S, Liang F, Rothenberg E, Heguy A, Morley GE, Coetzee WA, Trayanova NA, Ackerman MJ, van Veen TAB, Valdivia HH and Delmar M. Plakophilin-2 is required for transcription of genes that control calcium cycling and cardiac rhythm. Nat Commun. 2017;8:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Flier A, Gaspar AC, Thorsteinsdottir S, Baudoin C, Groeneveld E, Mummery CL and Sonnenberg A. Spatial and temporal expression of the beta1D integrin during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:472–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belkin AM, Zhidkova NI, Balzac F, Altruda F, Tomatis D, Maier A, Tarone G, Koteliansky VE and Burridge K. Beta 1D integrin displaces the beta 1A isoform in striated muscles: localization at junctional structures and signaling potential in nonmuscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:211–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akdis D, Brunckhorst C, Duru F and Saguner AM. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy: Electrical and Structural Phenotypes. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2016;5:90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada H, Lai NC, Kawaraguchi Y, Liao P, Copps J, Sugano Y, Okada-Maeda S, Banerjee I, Schilling JM, Gingras AR, Asfaw EK, Suarez J, Kang SM, Perkins GA, Au CG, Israeli-Rosenberg S, Manso AM, Liu Z, Milner DJ, Kaufman SJ, Patel HH, Roth DM, Hammond HK, Taylor SS, Dillmann WH, Goldhaber JI and Ross RS. Integrins protect cardiomyocytes from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4294–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan J, Xie W, Betzenhauser M, Reiken S, Chen BX, Wronska A and Marks AR. Calcium leak through ryanodine receptors leads to atrial fibrillation in 3 mouse models of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2012;111:708–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voigt N, Heijman J, Wang Q, Chiang DY, Li N, Karck M, Wehrens XHT, Nattel S and Dobrev D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of atrial arrhythmogenesis in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;129:145–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purohit A, Rokita AG, Guan X, Chen B, Koval OM, Voigt N, Neef S, Sowa T, Gao Z, Luczak ED, Stefansdottir H, Behunin AC, Li N, El-Accaoui RN, Yang B, Swaminathan PD, Weiss RM, Wehrens XH, Song LS, Dobrev D, Maier LS and Anderson ME. Oxidized Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II triggers atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2013;128:1748–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelu MG, Sarma S, Sood S, Wang S, van Oort RJ, Skapura DG, Li N, Santonastasi M, Muller FU, Schmitz W, Schotten U, Anderson ME, Valderrabano M, Dobrev D and Wehrens XH. Calmodulin kinase II-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak promotes atrial fibrillation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1940–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng H, Lederer MR, Lederer WJ and Cannell MB. Calcium sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C148–C159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng H, Lederer WJ and Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kam CY, Dubash AD, Magistrati E, Polo S, Satchell KJF, Sheikh F, Lampe PD and Green KJ. Desmoplakin maintains gap junctions by inhibiting Ras/MAPK and lysosomal degradation of connexin-43. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3219–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin S, Dimitri CA, Yoon SO, Dowdle W and Blenis J. ERK2 but not ERK1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation via DEF motif-dependent signaling events. Mol Cell. 2010;38:114–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lobert VH, Brech A, Pedersen NM, Wesche J, Oppelt A, Malerod L and Stenmark H. Ubiquitination of alpha 5 beta 1 integrin controls fibroblast migration through lysosomal degradation of fibronectin-integrin complexes. Dev Cell. 2010;19:148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyon RC, Mezzano V, Wright AT, Pfeiffer E, Chuang J, Banares K, Castaneda A, Ouyang K, Cui L, Contu R, Gu Y, Evans SM, Omens JH, Peterson KL, McCulloch AD and Sheikh F. Connexin defects underlie arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in a novel mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1134–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basso C, Czarnowska E, Della Barbera M, Bauce B, Beffagna G, Wlodarska EK, Pilichou K, Ramondo A, Lorenzon A, Wozniek O, Corrado D, Daliento L, Danieli GA, Valente M, Nava A, Thiene G and Rampazzo A. Ultrastructural evidence of intercalated disc remodelling in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: an electron microscopy investigation on endomyocardial biopsies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1847–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huke S and Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation at Serine 2030, 2808 and 2814 in rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Makarewich CA, Kubo H, Wang W, Duran JM, Li Y, Berretta RM, Koch WJ, Chen X, Gao E, Valdivia HH and Houser SR. Hyperphosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor at serine 2808 is not involved in cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;110:831–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Respress JL, van Oort RJ, Li N, Rolim N, Dixit SS, deAlmeida A, Voigt N, Lawrence WS, Skapura DG, Skardal K, Wisloff U, Wieland T, Ai X, Pogwizd SM, Dobrev D and Wehrens XH. Role of RyR2 phosphorylation at S2814 during heart failure progression. Circ Res. 2012;110:1474–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao B, Sutherland C, Walsh MP and Chen SR. Protein kinase A phosphorylation at serine-2808 of the cardiac Ca2+-release channel (ryanodine receptor) does not dissociate 12.6-kDa FK506-binding protein (FKBP12.6). Circ Res. 2004;94:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarado FJ, Chen X and Valdivia HH. Ablation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor phospho-site Ser2808 does not alter the adrenergic response or the progression to heart failure in mice. Elimination of the genetic background as critical variable. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;103:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benkusky NA, Weber CS, Scherman JA, Farrell EF, Hacker TA, John MC, Powers PA and Valdivia HH. Intact beta-adrenergic response and unmodified progression toward heart failure in mice with genetic ablation of a major protein kinase A phosphorylation site in the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res. 2007;101:819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao B, Zhong G, Obayashi M, Yang D, Chen K, Walsh MP, Shimoni Y, Cheng H, Ter Keurs H and Chen SR. Ser-2030, but not Ser-2808, is the major phosphorylation site in cardiac ryanodine receptors responding to protein kinase A activation upon beta-adrenergic stimulation in normal and failing hearts. Biochem J. 2006;396:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JC, Perez-Hernandez M, Alvarado FJ, Maurya SR, Montnach J, Yin Y, Zhang M, Lin X, Vasquez C, Heguy A, Liang FX, Woo SH, Morley GE, Rothenberg E, Lundby A, Valdivia HH, Cerrone M and Delmar M. Disruption of Ca(2+)i Homeostasis and Connexin 43 Hemichannel Function in the Right Ventricle Precedes Overt Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy in Plakophilin-2-Deficient Mice. Circulation. 2019;140:1015–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Q, Xiao J, Jiang D, Wang R, Vembaiyan K, Wang A, Smith CD, Xie C, Chen W, Zhang J, Tian X, Jones PP, Zhong X, Guo A, Chen H, Zhang L, Zhu W, Yang D, Li X, Chen J, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Cheng H, Feldman AM, Song LS, Fill M, Back TG and Chen SR. Carvedilol and its new analogs suppress arrhythmogenic store overload-induced Ca2+ release. Nat Med. 2011;17:1003–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corrado D, Wichter T, Link MS, Hauer R, Marchlinski F, Anastasakis A, Bauce B, Basso C, Brunckhorst C, Tsatsopoulou A, Tandri H, Paul M, Schmied C, Pelliccia A, Duru F, Protonotarios N, Estes NA 3rd, McKenna WJ, Thiene G, Marcus FI and Calkins H. Treatment of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: an international task force consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3227–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen H, Valle G, Furlan S, Nani A, Gyorke S, Fill M and Volpe P. Mechanism of calsequestrin regulation of single cardiac ryanodine receptor in normal and pathological conditions. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142:127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tu Q, Velez P, Brodwick M and Fill M. Streaming potentials reveal a short ryanodine-sensitive selectivity filter in cardiac Ca2+ release channel. Biophys J. 1994;67:2280–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou Q, Peng X, Liu X, Chen L, Xiong Q, Shen Y, Xie J, Xu Z, Huang L, Hu J, Wan R and Hong K. FAT10 attenuates hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by stabilizing caveolin-3. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;116:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang C, Chen B, Guo A, Zhu Y, Miller JD, Gao S, Yuan C, Kutschke W, Zimmerman K, Weiss RM, Wehrens XH, Hong J, Johnson FL, Santana LF, Anderson ME and Song LS. Microtubule-mediated defects in junctophilin-2 trafficking contribute to myocyte transverse-tubule remodeling and Ca2+ handling dysfunction in heart failure. Circulation. 2014;129:1742–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu W, Wang C, Hu J, Wan R, Yu J, Xie J, Ma J, Guo L, Ge J, Qiu Y, Chen L, Liu H, Yan X, Liu X, Ye J, He W, Shen Y, Wang C, Mohler PJ and Hong K. Ankyrin-B Q1283H Variant Linked to Arrhythmias Via Loss of Local Protein Phosphatase 2A Activity Causes Ryanodine Receptor Hyperphosphorylation. Circulation. 2018;138:2682–2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Chen B, Huang CK, Guo A, Wu J, Zhang X, Chen R, Chen C, Kutschke W, Weiss RM, Boudreau RL, Margulies KB, Hong J and Song LS. Targeting Calpain for Heart Failure Therapy: Implications From Multiple Murine Models. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3:503–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song LS, Sobie EA, McCulle S, Lederer WJ, Balke CW and Cheng H. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4305–4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu CY, Chen B, Jiang YP, Jia Z, Martin DW, Liu S, Entcheva E, Song LS and Lin RZ. Calpain-dependent cleavage of junctophilin-2 and T-tubule remodeling in a mouse model of reversible heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song LS, Guia A, Muth JN, Rubio M, Wang SQ, Xiao RP, Josephson IR, Lakatta EG, Schwartz A and Cheng H. Ca(2+) signaling in cardiac myocytes overexpressing the alpha(1) subunit of L-type Ca(2+) channel. Circ Res. 2002;90:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picht E, Zima AV, Blatter LA and Bers DM. SparkMaster: automated calcium spark analysis with ImageJ. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1073–C1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li B, Shen W, Peng H, Li Y, Chen F, Zheng L, Xu J and Jia L. Fibronectin 1 promotes melanoma proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting apoptosis and regulating EMT. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:3207–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Q, Deng C, Rao F, Modi RM, Zhu J, Liu X, Mai L, Tan H, Yu X, Lin Q, Xiao D, Kuang S and Wu S. Silencing of desmoplakin decreases connexin43/Nav1.5 expression and sodium current in HL1 cardiomyocytes. Molecular medicine reports. 2013;8:780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.