Abstract

Background

Many studies on COVID-19 have reported diabetes to be associated with severe disease and mortality, however, the data is conflicting. The objectives of this meta-analysis were to explore the relationship between diabetes and COVID-19 mortality and severity, and to determine the prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

We searched the PubMed for case-control studies in English, published between Jan 1 and Apr 22, 2020, that had data on diabetes in patients with COVID-19. The frequency of diabetes was compared between patients with and without the composite endpoint of mortality or severity. Random effects model was used with odds ratio as the effect size. We also determined the pooled prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Heterogeneity and publication bias were taken care by meta-regression, sub-group analyses, and trim and fill methods.

Results

We included 33 studies (16,003 patients) and found diabetes to be significantly associated with mortality of COVID-19 with a pooled odds ratio of 1.90 (95% CI: 1.37–2.64; p < 0.01). Diabetes was also associated with severe COVID-19 with a pooled odds ratio of 2.75 (95% CI: 2.09–3.62; p < 0.01). The combined corrected pooled odds ratio of mortality or severity was 2.16 (95% CI: 1.74–2.68; p < 0.01). The pooled prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19 was 9.8% (95% CI: 8.7%–10.9%) (after adjusting for heterogeneity).

Conclusions

Diabetes in patients with COVID-19 is associated with a two-fold increase in mortality as well as severity of COVID-19, as compared to non-diabetics. Further studies on the pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic implications need to be done.

Keywords: Coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, nCoV-2019, Novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Diabetes mellitus

1. Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a new disease, which within four months of its origin in Wuhan, China, has now spread to more than two hundred countries around the world, affecting more than 2,818,000 people and has caused more than 196,000 deaths, as of April 25, 2020 [1]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared COVID-19 a pandemic because of alarming levels of its spread, severity and inaction [2]. COVID-19 is caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is sufficiently genetically divergent from the closely related Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV), to be considered a new human-infecting betacoronavirus [3]. It mainly affects the respiratory tract and the illness ranges in severity from asymptomatic or mild to severe or critical disease. Although the current estimate of the case fatality rate of COVID-19 is < 5%, up to 15–18% of patients may become severe or critically ill, some of them requiring ICU care and mechanical ventilation [4].

Since COVID-19 is a new disease, knowledge about this disease is still incomplete and evolving. Many case-control studies have shown that patients of COVID-19, who have underlying diabetes mellitus, develop a severe clinical course, and also have increased mortality. However, most of these studies have small sample size, and the data in them are heterogenous and conflicting. In addition, the data on prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19 is also not clear.

Hence, this meta-analysis was conducted with the primary objective of exploring the relationship between underlying diabetes and severity and mortality of COVID-19 disease; and with the secondary objective of determining the prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19.

2. Materials and methods

Since, this is a meta-analysis, therefore an institutional board or an ethics committee approval was not required. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were consulted during the stages of design, analysis, and reporting of this meta-analysis [[5], [6], [7]]. The protocol of this meta-analysis is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) vide registration number CRD42020181756 and is available in full on the NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) website (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=181756).

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

Three authors (AK, SAA and SK) independently searched, screened and selected the studies according to the search, inclusion and exclusion criteria. PubMed database was searched for papers in English language using the following keywords: “2019-nCoV”, “nCoV-2019”, “novel Coronavirus 2019″, “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “coronavirus”, “coronavirus covid-19”, and “corona virus”. Since the first report of COVID-19 disease was published on December 31, 2019 [8], we limited our search to articles published since January 01, 2020, and the last search was performed on April 22, 2020. Since there is a high likelihood of duplicate publications on COVID-19 [9], especially, same set of patients being reported in English as well as Chinese or other languages, hence we restricted our search to papers published in English language only. For the same reason we restricted our search to PubMed database only and did not search other databases. In addition, each included study was carefully evaluated for study setting and author list to exclude any duplicate publication.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies were as follows:

-

(1)

The studies should be in English language in the PubMed database.

-

(2)

The study design should be case-control and should have categorized the patients into two or more groups depending on the severity, clinical course, or mortality of the patients with COVID-19 (i.e. composite endpoint). Studies without this categorization were not included. The study should have data of diabetes mellitus in each group.

-

(3)

The study should be observational (retrospective or prospective). Interventional studies such as controlled or uncontrolled drug trials were excluded.

-

(4)

The study should have included at least 100 patients of COVID-19.

-

(5)

The participants should be adult patients with COVID-19. Studies describing exclusively pediatric population were excluded, however, studies which had both adult and pediatric patients were included. Studies describing exclusively pregnant women were also excluded.

2.2. Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each study: date of online publication, PMID number, study setting, total number of patients, their demographic data, number of patients with composite endpoint, and number of patients with diabetes mellitus among patients with or without the composite endpoint. For studies with missing data, the corresponding authors of those studies were contacted with a request to provide the missing data.

2.3. Study outcome

The primary outcome of interest was the occurrence of composite endpoint which for the purpose of our study was labelled as ‘severe clinical course’ and defined as occurrence of one of the two endpoints depending on each study’s individual endpoint:

-

1.

For studies comparing survival and mortality – mortality of COVID-19 patients was taken as the composite endpoint;

-

2.For studies not having mortality as the endpoint, one of the following were chosen as the composite endpoint of ‘severe disease’, depending on study’s individual endpoint:

-

a.Patients requiring invasive ventilation; or

-

b.Patients requiring ICU care; or

-

c.Patients having progressive disease; or

-

d.Patients having refractory disease; or

- e.

-

a.

Patients not having any of the above features of ‘severe clinical course’ were categorized into ‘good clinical course’.

The secondary outcome of interest was to study the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with COVID-19.

2.4. Assessment of quality of studies

For the assessment of quality of studies, including the risk of bias, the National Institute of Health (NIH) tool for case-control studies was used. This tool has been developed jointly by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Research Triangle Institute International [14]. It uses a composite score of twelve domains, with each domain scored as ‘1’ or ‘0’ depending on the response ‘yes’ or ‘no’, respectively. The studies were categorized as good quality if they scored ≥8 points, fair quality if they scored 6–7 points, and poor quality if they scored <6 points.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The categorical data was displayed as n and % and continuous data as mean and SD. If the study had reported the data as median with IQR or range, the method described by Wan et al. was used to calculate the mean and SD [15].

To study the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with COVID-19, pooled proportion and 95% confidence interval (CI) was taken as the effect size. First the raw proportion from each study was extracted and transformed with the Freeman-Tukey double arcine method to stabilize the variance [16], then the pooled proportion was obtained using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects model [17].

To study the association of diabetes mellitus with the composite endpoint (severe clinical course), pooled odds ratio (with 95% CI) was taken as the effect size. We performed the meta-analysis using the generic inverse variance approach and DerSimonian-Laird random effects model [17]. A p value of <0.05 was used to show statistically significant association. The meta-analysis was sub-grouped according to the composite endpoint of severe disease and mortality.

To assess the heterogeneity among studies I2 statistic was calculated. An I2 value > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. To take care of heterogeneity among the studies, and to calculate a more conservative result, the odds ratios were pooled using only the random effects model. To explore the source of heterogeneity meta-regression analysis was done using age, type of composite endpoint (severity versus mortality), country of study (China versus others), number of patients, quality score, and quality type (good versus fair) as co-variates. In addition, if the heterogeneity among the studies was ≥50%, a sensitivity analysis was also performed after identifying and removing the outlier studies.

We evaluated the publication bias through visual inspection of funnel plot and Begg [18] and Egger [19] tests. When the funnel plot was symmetrical and the p value of Begg and Egger tests were >0.05, no significant publication bias was considered to exist in the meta-analysis. However, if publication bias was found, a trim and fill analysis of Duval and Tweedie [20] was used to evaluate the number of missing studies, and recalculation of the pooled odds ratio was done after addition of those missing hypothetical studies.

Review Manager software (version 5.3.5, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark), OpenMetaAnalyst software (version 10.12) [21], JASP software (version 0.12.1, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and Microsoft Excel (version 16.35) were employed for the meta-analysis and statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and data collection

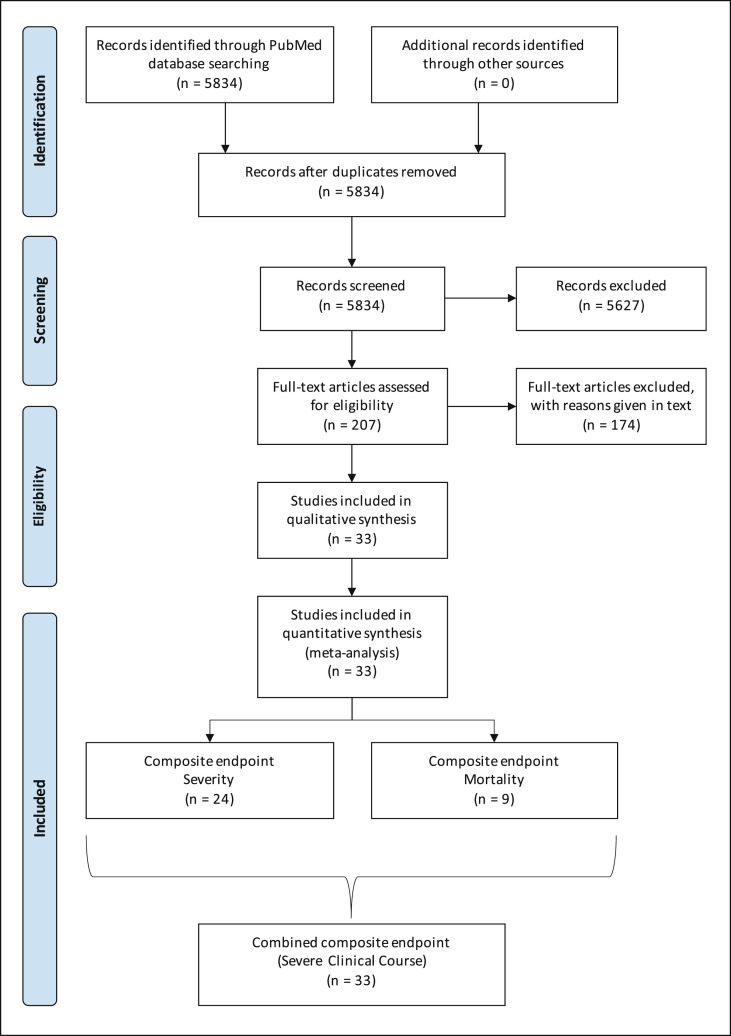

Using the keywords “2019-nCoV”, “nCoV-2019”, “novel Coronavirus 2019″, “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “coronavirus”, “coronavirus covid-19”, and “corona virus” and limiting the Entrez date from 01-Jan-2020 through 22-Apr-2020, initially 5834 publications in English language were retrieved from the PubMed database, which were screened for relevance (Fig. 1 ). After carefully going through the abstracts and full texts (if needed) of these publications, only 207 potentially relevant studies were selected and evaluated in detail for potential inclusion. Of these 174 studies were excluded because of the following reasons: (1) 144 studies did not have comparative data on COVID-19 patients with and without composite endpoint; (2) 22 studies were small with less than 100 participants; (3) 7 studies did not have diabetes as one of the comparative factors; and (4) 1 study was a duplicate publication. Hence, remaining 33 studies were included in the qualitative as well as quantitative synthesis meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing the flow of study selection.

3.2. Characteristics and quality of the included studies

The study characteristics of the 33 included studies are given in Table 1 . The online publication date of the studies in the PubMed database was from February 7, 2020 through April 17, 2020. Twenty out of 33 (61%) studies were from single centres, while remaining 13 (39%) were multi-centre studies. Most studies (30/33, 91%) were from mainland China, and of the remaining 3 studies, two (6%) were from USA, and one (3%) from France. The total included patients were 16,003, and of them 8849 (55%) were reported from Mainland China, 7030 (44%) from USA, and 124 (1%) from France. The median number of patients included in the studies was 214 (IQR: 139–368).

Table 1.

Characteristics and quality of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Date of publication | PMID | Setting | Remarks | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang D [55] | 07-Feb-20 | 32031570 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Zhang JJ [56] | 19-Feb-20 | 32077115 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Guan WJ [57] | 28-Feb-20 | 32109013 | 552 hospitals in 30 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in mainland China | 9 | |

| Ruan Q [58] | 03-Mar-20 | 32125452 | Two centres in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Zhou F [59] | 11-Mar-20 | 32171076 | Two hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Wu C [60] | 13-Mar-20 | 32167524 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Mo P [61] | 16-Mar-20 | 32173725 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Shi Y [62] | 18-Mar-20 | 32188484 | Multi-centre in Zhejiang Province, China | 8 | |

| Zhang X [63] | 20-Mar-20 | 32205284 | Multi-centre in Zhejiang Province, China | 9 | |

| Deng Y [64] | 20-Mar-20 | 32209890 | Two tertiary hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 8 | |

| Wan S [65] | 21-Mar-20 | 32198776 | Multi-centre in Chongqing, China | 9 | |

| Chen T [66] | 26-Mar-20 | 32217556 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Wang L [67] | 30-Mar-20 | 32240670 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | Only elderly >60 years patients | 9 |

| Wang L [68] | 31-Mar-20 | 32229732 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Cai Q [69] | 02-Apr-20 | 32239761 | Single centre in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China | 9 | |

| Cao J [70] | 02-Apr-20 | 32239127 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| CDC COVID-19 [22] | 03-Apr-20 | 32240123 | Cases reported from all over US to CDC, USA | Registry data | 7 |

| Wang X [71] | 03-Apr-20 | 32251842 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | Only non-critical patients | 9 |

| Wang Y [72] | 08-Apr-20 | 32267160 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | Only ICU patients | 9 |

| Du RH [73] | 08-Apr-20 | 32269088 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Zhang G [74] | 09-Apr-20 | 32311650 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Zheng F [75] | 09-Apr-20 | 32271459 | Single centre in Changsha, Hunan Province, China | 8 | |

| Simonnet A [76] | 09-Apr-20 | 32271993 | Single centre in Lille, France | Only ICU patients | 9 |

| Feng Y [77] | 10-Apr-20 | 32275452 | Three hospitals in China | 9 | |

| Yang Z [78] | 10-Apr-20 | 32275643 | Single centre in Shanghai, China | 9 | |

| Liu Y [79] | 10-Apr-20 | 32283162 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Mao L [80] | 10-Apr-20 | 32275288 | Multi-centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Shen L [81] | 10-Apr-20 | 32283164 | Multi-centre in Xiangyang, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Zhang R [82] | 11-Apr-20 | 32279115 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Li X [83] | 12-Apr-20 | 32294485 | Single centre in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China | 9 | |

| Wei YY [84] | 16-Apr-20 | 32305487 | Multi-centre in Anhui Province, China | 8 | |

| Wan S [85] | 16-Apr-20 | 32297671 | Single centre in Chongqing, China | 9 | |

| Goyal P [86] | 17-Apr-20 | 32302078 | Two hospitals in New York City, USA | 8 |

The quality of study was assessed using the NIH tool for case-control studies [14] and the results are shown in Table 1. The scores were as follows: 9/12 score (27 studies [82%]); 8/12 score (5 studies [15%]); and 7/12 score (1 study [3%]). Out of the twelve domains assessed by this tool, the three domains in which all the studies were given ‘0’ score were: sample size justification, blinding of assessors, and adjusting for confounding variables. Thus 32 studies (97%) were judged as good quality (scores of ≥8) and remaining 1 study (3%) was judged as fair quality (scores 6–7). None of the included study was judged poor. The single study with fair quality was the paper published by the CDC, USA on the COVID-19 cases reported to it from all over the US [22]. Thus, it was a registry data, rather than a hospital-based study.

3.3. Characteristics of the included patients

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the included patients. The total number of patients was 16,003, with proportion of males being 54% (5068/9366). Thus the male: female ratio was approximately 1.2 : 1. The pooled mean age was 52.6 ± 17.4 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included patients.

| Author | Number of patients | Age (years) |

Males |

Patients with composite endpoint |

Patients with diabetes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | % | n | % | Reason | n | % | ||

| Wang D [55] | 138 | 55.3 | 19.50 | 75 | 54% | 36 | 26% | ICU | 14 | 10% |

| Zhang JJ [56] | 140 | 56.5 | 11.80 | 71 | 51% | 58 | 41% | Criteria | 17 | 12% |

| Guan WJ [57] | 1099 | 46.7 | 17.10 | 640 | 58% | 173 | 16% | Criteria | 81 | 7% |

| Ruan Q [58] | 150 | 57.7 | 12.50 | 102 | 68% | 68 | 45% | Died | 25 | 17% |

| Zhou F [59] | 191 | 56.3 | 15.70 | 119 | 62% | 54 | 28% | Died | 36 | 19% |

| Wu C [60] | 201 | 51.3 | 12.70 | 128 | 64% | 84 | 42% | ARDS | 22 | 11% |

| Mo P [61] | 155 | 54.0 | 18.00 | 86 | 55% | 85 | 55% | Refractory | 15 | 10% |

| Shi Y [62] | 487 | 46.0 | 19.00 | 259 | 53% | 49 | 10% | Criteria | 29 | 6% |

| Zhang X [63] | 597 | 45.3 | 14.34 | 328 | 55% | 64 | 11% | Criteria | 48 | 8% |

| Deng Y [64] | 225 | 55.4 | 19.04 | 124 | 55% | 109 | 48% | Died | 26 | 12% |

| Wan S [65] | 135 | 46.0 | 14.24 | 72 | 53% | 40 | 30% | Criteria | 12 | 9% |

| Chen T [66] | 274 | 58.7 | 19.38 | 171 | 62% | 113 | 41% | Died | 47 | 17% |

| Wang L [67] | 339 | 70.0 | 8.19 | 166 | 49% | 65 | 19% | Died | 54 | 16% |

| Wang L [68] | 116 | 53.7 | 23.27 | 67 | 58% | 57 | 49% | Criteria | 18 | 16% |

| Cai Q [69] | 298 | 47.2 | 20.86 | 145 | 49% | 58 | 19% | Criteria | 18 | 6% |

| Cao J [70] | 102 | 52.7 | 22.56 | 53 | 52% | 17 | 17% | Died | 11 | 11% |

| CDC COVID-19 [22] | 6637 | No data | No data | No data | No data | 457 | 7% | ICU | 730 | 11% |

| Wang X [71] | 1012 | 51.3 | 11.30 | 524 | 52% | 100 | 10% | Progression | 27 | 3% |

| Wang Y [72] | 344 | 62.7 | 14.89 | 179 | 52% | 133 | 39% | Died | 64 | 19% |

| Du RH [73] | 179 | 57.6 | 13.70 | 97 | 54% | 21 | 12% | Died | 33 | 18% |

| Zhang G [74] | 221 | 53.5 | 20.52 | 108 | 49% | 55 | 25% | Criteria | 22 | 10% |

| Zheng F [75] | 161 | 45.2 | 17.58 | 80 | 50% | 30 | 19% | Criteria | 7 | 4% |

| Simonnet A [76] | 124 | 60.3 | 14.25 | 91 | 73% | 85 | 69% | Ventilation | 28 | 23% |

| Feng Y [77] | 476 | 52.3 | 17.85 | 271 | 57% | 124 | 26% | Criteria | 49 | 10% |

| Yang Z [78] | 273 | 49.1 | 13.75 | 134 | 49% | 71 | 26% | Progression | 18 | 7% |

| Liu Y [79] | 245 | 54.0 | 16.90 | 114 | 47% | 33 | 13% | Died | 23 | 9% |

| Mao L [80] | 214 | 52.7 | 15.50 | 87 | 41% | 88 | 41% | Criteria | 30 | 14% |

| Shen L [81] | 119 | 49.3 | 17.26 | 56 | 47% | 20 | 17% | Criteria | 12 | 10% |

| Zhang R [82] | 120 | 45.4 | 15.60 | 43 | 36% | 30 | 25% | Criteria | 7 | 6% |

| Li X [83] | 548 | 59.0 | 15.61 | 279 | 51% | 269 | 49% | Criteria | 83 | 15% |

| Wei YY [84] | 167 | 42.3 | 15.29 | 95 | 57% | 30 | 18% | Criteria | 11 | 7% |

| Wan S [85] | 123 | 46.2 | 15.15 | 66 | 54% | 21 | 17% | Criteria | 8 | 7% |

| Goyal P [86] |

393 |

61.5 |

18.68 |

238 |

61% |

130 |

33% |

Ventilation |

99 |

25% |

| Total | 16003 | 52.6 | 17.37 | 5068 | 54% | 2827 | 18% | 1724 | 11% | |

Of the 16,003 patients, 2827 (18%) patients had the composite endpoint (labelled ‘severe clinical course’). The reasons for composite endpoint were mortality in 9 studies (613/2827 [22%] patients) and severity in 24 studies (2214/2827 [78%] patients). Of the 24 studies having severity as the composite endpoint, the reasons were as follows: Pre-defined criteria (16 studies); ICU requirement versus no requirement (2 studies); invasive ventilation requirement versus no requirement (2 studies); progressive disease versus stable disease (2 studies); refractory disease versus responsive disease (1 study); and ARDS versus no ARDS (1 study).

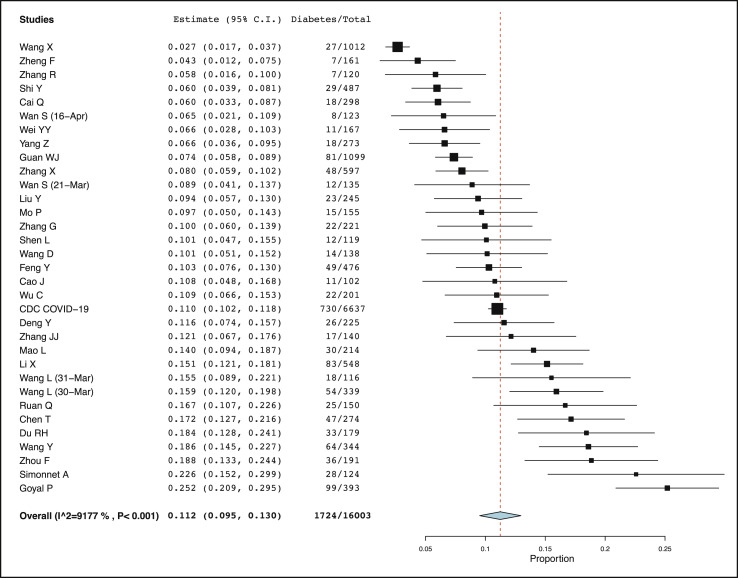

3.4. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with COVID-19 (secondary outcome)

Diabetes was present in 1724 patients out of total 16,003 patients of COVID-19. The pooled prevalence of diabetes was calculated to be 11.2% (95% CI: 9.5%–13.0%) by using the Freeman-Tukey double arcine transformation and DerSimonian-Laird random effects model (Fig. 2 ). However, the heterogeneity among the studies was substantial with an I2 value of 92%. To explore the source of heterogeneity meta-regression analyses were done using age, type of composite endpoint (severity versus mortality), country of study (China versus others), number of patients, quality score, and quality type (good versus fair) as co-variates (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The results of meta-regression showed that proportion of diabetes in patients with COVID-19 was influenced by age (with studies with higher patient age having higher proportion of diabetes, p < 0.001), type of composite endpoint (with studies reporting mortality endpoint having higher proportion of diabetes, p = 0.004), and country of study (with studies outside of China having higher proportion of diabetes, p = 0.006). There was no influence of number of patients in studies or quality score of studies. A sub-group analysis revealed that proportion of diabetes mellitus in China was 10.5% (95% CI: 8.7%–12.3%) while in countries other than China (mainly USA) it was 19.3% (95% CI: 8.4%–30.3%), but with high heterogeneity (data not shown). A sensitivity analysis was also done by excluding 13 outlier studies, which revealed a pooled prevalence of diabetes to be 9.8% (95% CI: 8.7%–10.9%) in patients with COVID-19 with an acceptable I2 value of 46% (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled proportion of diabetes mellitus in COVID-19 patients.

3.5. Association of diabetes mellitus with mortality or severity of COVID-19 (primary outcome)

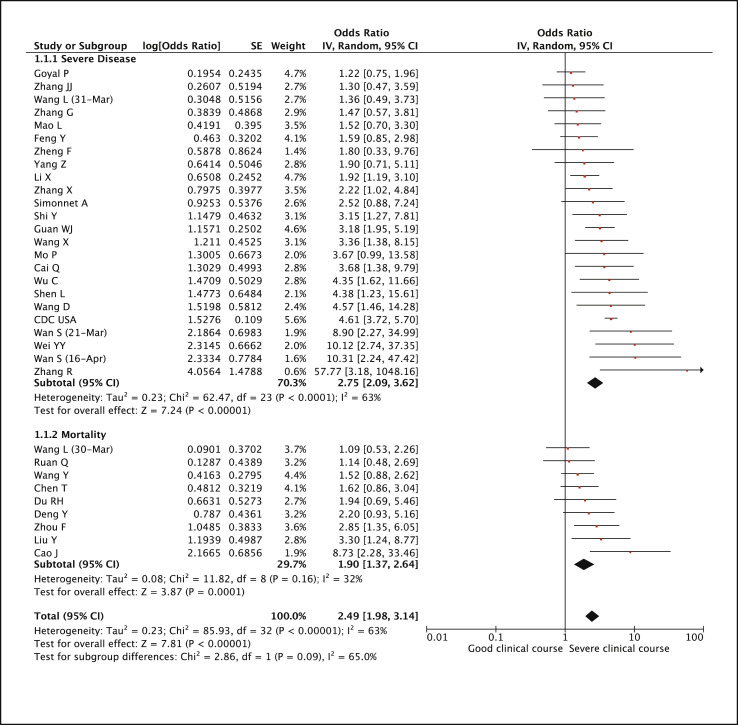

Of the 33 included studies in this meta-analysis, 24 had used severity as the composite endpoint and 9 had used mortality as the composite endpoint. Presence of diabetes was found to be significantly associated with severe COVID-19 (pooled odds ratio 2.75 [95% CI: 2.09–3.62; p < 0.01]) as well as mortality due to COVID-19 (pooled odds ratio 1.90 [95% CI: 1.37–2.64; p < 0.01]). The combine pooled odds ratio for both the composite endpoints (labelled as severe clinical course) was 2.49 (95% CI: 1.98–3.14; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing pooled odds ratio of diabetes mellitus associated with severe clinical course including mortality.

For the mortality endpoint, the heterogeneity among the studies was low (I2 = 32%), while for the severity endpoint the heterogeneity among the studies was substantial (I2 = 63%). Thus the combined heterogeneity was also substantial (I2 = 63%). To explore the source of heterogeneity meta-regression analyses were done using age, type of composite endpoint (severity versus mortality), country of study (China versus others), number of patients, quality score, and quality type (good versus fair) as co-variates (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). The results of meta-regression showed that odds ratio was influenced by age (with studies with higher patients’ age having lower odds ratio, p < 0.001). In addition it was found that the CDC study from USA [22], which was of not good quality (being a registry data), significantly influenced the outcome of this meta-analysis and was mainly responsible for the significant heterogeneity. Hence, a sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding this study, which again revealed a significant combined pooled odds ratio of 2.33 (95% CI: 1.90–2.85; p < 0.01) and an I2 value of 41% (acceptable heterogeneity) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

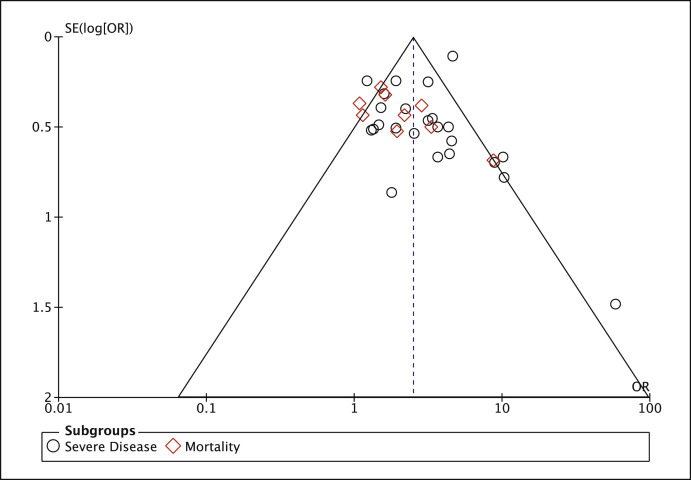

3.6. Influence of publication bias

For the main outcome of this meta-analysis, i.e. association of diabetes mellitus with severe clinical course of COVID-19, publication bias was evaluated through the visual inspection of funnel plot and Begg and Egger tests [18,19]. The funnel plot (Fig. 4 ) was found to be mildly asymmetric and the Begg’s rank correlation test for funnel plot asymmetry (Kendall’s τ = 0.439) as well as Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry (z = 2.561) were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Hence, a trim and fill analysis of Duval and Tweedie [20] was used to evaluate the number of missing studies and we recalculated the pooled odds ratio with the addition of those missing hypothetical studies. The recalculated pooled odds ratio of association of diabetes mellitus with severe clinical course of COVID-19 was 2.26 (95% CI: 1.78–2.87; p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The redrawn funnel plot after addition of four missing hypothetical studies was now symmetrical (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot for evaluation of publication bias.

After adjusting for both, heterogeneity as well as publication bias, the corrected pooled odds ratio for diabetes mellitus being associated with severe clinical course of COVID-19 (i.e.both mortality and severity) was still significant (2.16 [95% CI: 1.74–2.68]; p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

4. Discussion

To summarise the results of this meta-analysis of 33 studies (16,003 patients), we found diabetes mellitus to be significantly associated with mortality risk of COVID-19 with a pooled odds ratio of 1.90 (95% CI: 1.37–2.64; p < 0.01) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 32%). In addition, diabetes mellitus was associated with severe COVID-19, including risk of ARDS, ICU requirement, and invasive ventilatory requirement, with a pooled odds ratio of 2.75 (95% CI: 2.09–3.62; p < 0.01). The combined pooled odds ratio of diabetics developing severe COVID-19 or dying due to it (i.e. composite endpoint) was 2.49 (95% CI: 1.98–3.14; p < 0.01). After adjusting for both, heterogeneity among the studies as well as publication bias, the corrected pooled odds ratio for diabetes being associated with severe clinical course of COVID-19 was still significantly high (2.16 [95% CI: 1.74–2.68]; p < 0.01). As a secondary outcome, we also calculated the pooled prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with COVID-19, which was 11.2% (95% CI: 9.5%–13.0%) (uncorrected) and 9.8% (95% CI: 8.7%–10.9%) (after adjusting for heterogeneity).

There are many strengths of this meta-analysis. First, to the best of our knowledge this is the first large meta-analysis on specific influence of diabetes on severity of COVID-19, as well as on its mortality. In addition, we also studied the prevalence of diabetes among COVID-19 patients. Second, we have included a large number of studies, with patient population above sixteen thousand, spanning three continents. Third, we have included only large studies, with more that 100 patients, thus each study contributed a robust data on diabetes–COVID19 association without increasing heterogeneity. Fourth, we have avoided including any duplicate studies by limiting our search to single database, limiting search to English articles only, and carefully going through each included article’s study setting and author list. Fifth, while synthesizing results we have taken care of both heterogeneity as well as publication bias by appropriate statistical tools.

First discussing about the secondary outcome of our meta-analysis, we determined the corrected pooled prevalence of diabetes mellitus in COVID-19 patients to be close to 10%, with a higher prevalence in USA than China. Our results on prevalence are similar to a large Chinese nationwide study of 1590 patients which had shown the prevalence of diabetes in COVID-19 patients to be 8.2% [23]. Another small meta-analysis of 12 Chinese studies (2108 patients) by Fadini et al. [24] also reported the prevalence of diabetes in COVID-19 patients as 10.3%. Our study as well as these other previous studies indicate that the prevalence of diabetes in patients with COVID-19 is in the range of 10%, which is similar to the population prevalence of diabetes in the general population of China and the USA (10.9% and 11.1%, respectively) [25,26]. Thus our meta-analysis supports the previously held notion that the susceptibility of diabetic population to COVID-19 infection might not be increased but be similar to the non-diabetic population [27].

The primary and the more important outcome of our meta-analysis was to study the association of diabetes with mortality and severity of COVID-19 disease. We found that diabetic patients with COVID-19 are twice more likely to develop severe COVID-19 disease and twice more likely to die due to it (odds ratio close to 2 for severity as well as mortality). Thus patients with COVID-19 and diabetes are more likely to develop ARDS, need ICU care, need invasive ventilation, and are more vulnerable to succumb to it. Our results are similar to two small meta-analyses, by Fadini et al. (6 studies, 1687 patients) and Wang et al. (6 studies, 1558 patients), which gave odds ratio of 2.26 and 2.47, respectively, for diabetic patients developing more adverse disease due to SARS-CoV-2 infection [24,28]. Another systematic review of 7 studies by Singh et al. also suggested that diabetes is a determinant of severity and mortality of COVID-19 patients [29]. However, our meta-analysis is the largest with 33 studies, and we have now conclusively shown the association of diabetes with COVID-19 mortality as well as severity.

Whether diabetes is an independent determinant of severity was studied by Guo et al. in their case-control study from China [30], in which they compared diabetic and non-diabetic COVID-19 patients, and found that even in absence of other comorbidities, diabetics were at higher risk of severe pneumonia, uncontrolled inflammatory response, higher levels of tissue injury-related enzymes, and higher hypercoagulable state. Further they found, serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, D-dimer, IL-6, serum ferritin and coagulation index, were significantly higher in diabetic patients compared to those without, suggesting that patients with diabetes are more susceptible to an inflammatory storm that leads to worsening of COVID-19 [30].

The pathogenesis of increased mortality and severity of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes is still unclear. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 202–2004 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreaks in 2012 and 2015, had also resulted in increased severity and fatality in patients with diabetes mellitus [[31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. All these previous outbreaks were also caused by other coronaviruses, namely SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. To elucidate the mechanism of enhanced disease severity in diabetics following MERS-CoV infection, Kulcsar et al. [36] used an animal model in which mice were made susceptible to MERS-CoV infection by expressing human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), and type 2 diabetes was induced by administering a high-fat diet. Upon infection with MERS-CoV, diabetic mice had a prolonged phase of severe disease and delayed recovery that was independent of viral titres. Histological examination revealed that diabetic mice had delayed but prolonged systemic inflammation, fewer inflammatory monocyte/macrophages and CD4+ T cells, lower levels of chemokine ligand 2 and C-X-C motif chemokine 10 expression, lower levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin (IL) 6, IL 12b, and arginase 1 expression and higher levels of IL 17a expression. The data suggested that the increased disease severity observed in diabetes was likely due to a dysregulated immune response, which resulted in more severe and prolonged lung pathology [36]. Since patients with diabetes have multiple immune dysregulations such as phagocytic cell dysfunction, inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis, impaired T-cell mediated immune response, altered cytokine production, and ineffective microbial clearance [37], these dysregulated immune responses may result into a cytokine profile resembling secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, characterised by increased IL 2, IL 7, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, interferon-γ inducible protein 10, monocyte chemo-attractant protein 1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α, and TNFα [38,39].

In addition, type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronavirus infection also have shared pathogenic pathways, which has therapeutic implications [40]. Two of the coronavirus receptors, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and DPP4 are also transducers of metabolic pathways regulating glucose homeostasis, renal and cardiovascular physiology, and inflammation. DPP4 inhibitors are widely used in subjects with type 2 diabetes because of their effect of lowering blood glucose levels. However, the effects of DPP4 inhibition on the immune response in patients with diabetes is still controversial and not completely understood [41]. Two recent meta-analyses had shown that DPP4 inhibitors increased the risk of various infections [42,43] while a third meta-analysis showed that there is no increased risk of infections with DPP4 inhibitors [44]. Whether DPP4 inhibitors increase the susceptibility or severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection needs to be studied in future trials.

The results our meta-analysis has three major implications during the current COVID-19 pandemic. First, since diabetes can lead to severe COVID-19, its prevention in diabetics is imperative. It should be the responsibility of the treating physicians to advice their diabetic patients to take extra-precautions of social distancing and hand hygiene to protect themselves from coronavirus infection [45]. Second, there should be an increased vigilance in the out-patient clinics of diabetes for COVID-19, and the threshold for testing for this infection in diabetic patients should be lowered [46]. Third, any patient with COVID-19, who has co-morbid diabetes, should be taken as potentially serious, even though he or she may show only mild or no symptoms at presentation. These patients will need extra monitoring, and their threshold for hospital and ICU admission also needs to be lowered.

The results of our meta-analysis has also implications for India, which is often called the ‘Diabetes Capital’ of the world. According to the 2019 estimate, the age standardised diabetes prevalence in South-East Asia, including India, among ages 20–79 years, was estimated to be 11.3% (95% CI: 8.0%–15.9%), with the actual number of people with diabetes in India being more than 77 million [25,47]. Drivers of type 2 diabetes in south Asia include genetic and epigenetic factors, intrauterine and early life factors, high carbohydrate dietary patterns, and increase in physical inactivity [48]. All these factors, not only increase the prevalence of diabetes, but are also major factors in the causation of obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, with a resultant increase in morbidity and mortality. In fact, diabetes, along with cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease accounted for 4%, 27%, and 3% of deaths, respectively, in South Asia [49]. During the current COVID-19 pandemic, our meta-analysis, as well as multiple other studies have shown that COVID-19 is particularly more severe in patients with these comorbidities with increased hospitalization, ICU and ventilatory requirements [50,51]. With the huge population burden of diabetes in India, if urgent and strong measures are not taken to flatten the curve of COVID-19 pandemic in India, it will lead to disastrous consequences with overburdening of already stretched healthcare system of India. Especially, elderly population of India with comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac diseases will need special protection as enumerated in the preceding paragraph. Their blood sugars need to be better controlled and their health condition need to be better monitored, even in the face of lockdown, through measures such as tele-consultation and tele-medicine [52].

4.1. Limitations

Our meta-analysis has two limitations. We have shown that diabetes is associated with COVID-19 severity and mortality; however, it cannot be said whether diabetes is acting as an independent factor responsible for this severity and mortality, or it is just a confounding factor. Many conditions such as elderly age, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, often co-exist with diabetes, and each of these comorbidities have been shown to be associated with severe COVID-19 and its mortality. In spite of this limitation, the implication our meta-analysis will remain unchanged that diabetic need to be protected from COVID-19, and they will need extra care if infected. The second limitation of this meta-analysis is that we have not been able to document the role of glycemic control on the severity or mortality of COVID-19. It has been shown previously that poor glycemic control, in terms of high HbA1c, was significantly associated with increased risk of various infections [53,54]. However, none of the included studies on COVID-19 in our meta-analysis had evaluated glycemic control as one of the factors associated with severity and/or mortality; and this needs to be explored in further trials.

In conclusion, we have shown in this meta-analysis that presence of underlying diabetes in patients with COVID-19 is associated with two-fold increased risk of mortality, as well as two-fold increased risk of severity of COVID-19. This necessitates enhanced prevention of COVID-19 in diabetics, increased vigilance in patients of diabetes for COVID-19, and a lower threshold for monitoring, hospitalization, and ICU care if diabetics develop this infection. Results of our meta-analysis emphasizes the need for further investigation on the pathogenic mechanism of relationship between diabetes and COVID-19, and to explore its therapeutic implications.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Author contributions

AK designed the study. AK, SAA and SK searched, screened and selected the articles. AK, PS, NB and AS extracted the data from the articles. AK and PS performed data analysis and interpretation. AK drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed in writing and editing of the manuscript. AA supervised the study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Coronavirus update (live): 2,818,181 cases and 196,576 deaths from COVID-19 virus pandemic - worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ n.d. (accessed April 25, 2020)

- 2.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ. 2020;368:m1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun P., Qie S., Liu Z., Ren J., Li K., Xi J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Prisma Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., Olkin I., Williamson G.D., Rennie D. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283 doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. 2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wuhan Municipal Health Commission [Wuhan Municipal Health Commission on the current situation of pneumonia in our city] http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989 n.d. (accessed April 27, 2020)

- 9.Bauchner H., Golub R.M., Zylke J. Editorial concern-possible reporting of the same patients with COVID-19 in different reports. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected n.d. (accessed March 28, 2020)

- 11.State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine [Notice on the issuance of a new coronavirus infection pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (trial fifth version)] http://bgs.satcm.gov.cn/zhengcewenjian/2020-02-06/12847.html n.d. (accessed April 27, 2020)

- 12.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China Diagnosis and treatment protocol for COVID-19 (trial version 7) http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-03/29/c_78469.htm n.d. (accessed April 27, 2020)

- 13.Metlay J.P., Waterer G.W., Long A.C., Anzueto A., Brozek J., Crothers K. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American thoracic society and infectious diseases society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Study Quality Assessment Tools National Heart, lung, and blood Institute (NHLBI) https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools n.d. (accessed March 28, 2020)

- 15.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman M.F., Tukey J.W. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Contr Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace B.C., Dahabreh I.J., Trikalinos T.A., Lau J., Trow P., Schmid C.H. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. J Stat Software. 2012;49:1–15. doi: 10.18637/jss.v049.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC Covid-19 Response Team Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, february 12-march 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:382–386. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan W.-J., Liang W.-H., Zhao Y., Liang H.-R., Chen Z.-S., Li Y.-M. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadini G.P., Morieri M.L., Longato E., Avogaro A. Prevalence and impact of diabetes among people infected with SARS-CoV-2. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saeedi P., Petersohn I., Salpea P., Malanda B., Karuranga S., Unwin N. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L., Gao P., Zhang M., Huang Z., Zhang D., Deng Q. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. J Am Med Assoc. 2017;317:2515–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceriello A., Stoian A.P., Rizzo M. COVID-19 and diabetes management: what should be considered? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020:108151. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B., Li R., Lu Z., Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging. 2020;12:6049–6057. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh A.K., Gupta R., Ghosh A., Misra A. Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo W., Li M., Dong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Tian C. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020:e3319. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J.K., Feng Y., Yuan M.Y., Yuan S.Y., Fu H.J., Wu B.Y. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med. 2006;23:623–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth C.M., Matukas L.M., Tomlinson G.A., Rachlis A.R., Rose D.B., Dwosh H.A. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:2801–2809. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodek P. Diabetes and other comorbidities were associated with a poor outcome in the severe acute respiratory syndrome. ACP J Club. 2004;140:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuyama R., Nishiura H., Kutsuna S., Hayakawa K., Ohmagari N. Clinical determinants of the severity of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Publ Health. 2016;16:1203. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y.-M., Hsu C.-Y., Lai C.-C., Yen M.-F., Wikramaratna P.S., Chen H.-H. Impact of comorbidity on fatality rate of patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11307. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10402-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulcsar K.A., Coleman C.M., Beck S.E., Frieman M.B. Comorbid diabetes results in immune dysregulation and enhanced disease severity following MERS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angelidi A.M., Belanger M.J., Mantzoros C.S. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: what we know, how our patients should be treated now, and what should happen next. Metab Clin Exp. 2020:154245. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drucker D.J. Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iacobellis G. COVID-19 and diabetes: can DPP4 inhibition play a role? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108125. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richter B., Bandeira-Echtler E., Bergerhoff K., Lerch C.L. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006739. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006739.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amori R.E., Lau J., Pittas A.G. Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:194–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang W., Cai X., Han X., Ji L. DPP-4 inhibitors and risk of infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:391–404. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta R., Ghosh A., Singh A.K., Misra A. Clinical considerations for patients with diabetes in times of COVID-19 epidemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:211–212. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill M.A., Mantzoros C., Sowers J.R. Commentary: COVID-19 in patients with diabetes. Metab Clin Exp. 2020;107:154217. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Misra A., Gopalan H., Jayawardena R., Hills A.P., Soares M., Reza-Albarrán A.A. Diabetes in developing countries. J Diabetes. 2019;11:522–539. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hills A.P., Arena R., Khunti K., Yajnik C.S., Jayawardena R., Henry C.J. Epidemiology and determinants of type 2 diabetes in south Asia. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:966–978. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Misra A., Tandon N., Ebrahim S., Sattar N., Alam D., Shrivastava U. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease in South Asia: current status and future directions. BMJ. 2017;357:j1420. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh A.K., Gupta R., Misra A. Comorbidities in COVID-19: outcomes in hypertensive cohort and controversies with renin angiotensin system blockers. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghosh A., Gupta R., Misra A. Telemedicine for diabetes care in India during COVID19 pandemic and national lockdown period: guidelines for physicians. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Critchley J.A., Carey I.M., Harris T., DeWilde S., Hosking F.J., Cook D.G. Glycemic control and risk of infections among people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in a large primary care cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2127–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mor A., Dekkers O.M., Nielsen J.S., Beck-Nielsen H., Sørensen H.T., Thomsen R.W. Impact of glycemic control on risk of infections in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:227–236. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J.-J., Dong X., Cao Y.-Y., Yuan Y.-D., Yang Y.-B., Yan Y.-Q. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruan Q., Yang K., Wang W., Jiang L., Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mo P., Xing Y., Xiao Y., Deng L., Zhao Q., Wang H. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi Y., Yu X., Zhao H., Wang H., Zhao R., Sheng J. Host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and establishment of a host risk score: findings of 487 cases outside Wuhan. Crit Care. 2020;24:108. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2833-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X., Cai H., Hu J., Lian J., Gu J., Zhang S. Epidemiological, clinical characteristics of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with abnormal imaging findings. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng Y., Liu W., Liu K., Fang Y.-Y., Shang J., Zhou L. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chin Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wan S., Xiang Y., Fang W., Zheng Y., Li B., Hu Y. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L., He W., Yu X., Hu D., Bao M., Liu H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang L., Li X., Chen H., Yan S., Li D., Li Y. Coronavirus disease 19 infection does not result in acute kidney injury: an analysis of 116 hospitalized patients from wuhan, China. Am J Nephrol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000507471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cai Q., Huang D., Ou P., Yu H., Zhu Z., Xia Z. COVID-19 in a designated infectious diseases hospital outside Hubei Province, China. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao J., Tu W.-J., Cheng W., Yu L., Liu Y.-K., Hu X. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X., Fang J., Zhu Y., Chen L., Ding F., Zhou R. Clinical characteristics of non-critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Y., Lu X., Chen H., Chen T., Su N., Huang F. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Du R.-H., Liang L.-R., Yang C.-Q., Wang W., Cao T.-Z., Li M. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang G., Hu C., Luo L., Fang F., Chen Y., Li J. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104364. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng F., Tang W., Li H., Huang Y.-X., Xie Y.-L., Zhou Z.-G. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Changsha. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:3404–3410. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., Raverdy V., Noulette J., Duhamel A. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feng Y., Ling Y., Bai T., Xie Y., Huang J., Li J. COVID-19 with different severity: a multi-center study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0445OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Z., Shi J., He Z., Lü Y., Xu Q., Ye C. Predictors for imaging progression on chest CT from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Aging. 2020;12:6037–6048. doi: 10.18632/aging.102999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu Y., Du X., Chen J., Jin Y., Peng L., Wang H.H.X. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen L., Li S., Zhu Y., Zhao J., Tang X., Li H. Clinical and laboratory-derived parameters of 119 hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Xiangyang, Hubei province, China. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang R., Ouyang H., Fu L., Wang S., Han J., Huang K. CT features of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia according to clinical presentation: a retrospective analysis of 120 consecutive patients from Wuhan city. Eur Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06854-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li X., Xu S., Yu M., Wang K., Tao Y., Zhou Y. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wei Y.-Y., Wang R.-R., Zhang D.-W., Tu Y.-H., Chen C.-S., Ji S. Risk factors for severe COVID-19: evidence from 167 hospitalized patients in Anhui, China. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wan S., Yi Q., Fan S., Lv J., Zhang X., Guo L. Relationships among lymphocyte subsets, cytokines, and the pulmonary inflammation index in coronavirus (COVID-19) infected patients. Br J Haematol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bjh.16659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., Schenck E.J., Chen R., Jabri A. Clinical characteristics of covid-19 in New York city. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.