Abstract

Background

Many of the drugs being used in the treatment of the ongoing pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are associated with QT prolongation. Expert guidance supports electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring to optimize patient safety.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to establish an enhanced process for ECG monitoring of patients being treated for COVID-19.

Methods

We created a Situation Background Assessment Recommendation tool identifying the indication for ECGs in patients with COVID-19 and tagged these ECGs to ensure prompt over reading and identification of those with QT prolongation (corrected QT interval > 470 ms for QRS duration ≤ 120 ms; corrected QT interval > 500 ms for QRS duration > 120 ms). This triggered a phone call from the electrophysiology service to the primary team to provide management guidance and a formal consultation if requested.

Results

During a 2-week period, we reviewed 2006 ECGs, corresponding to 524 unique patients, of whom 103 (19.7%) met the Situation Background Assessment Recommendation tool–defined criteria for QT prolongation. Compared with those without QT prolongation, these patients were more often in the intensive care unit (60 [58.3%] vs 149 [35.4%]) and more likely to be intubated (32 [31.1%] vs 76 [18.1%]). Fifty patients with QT prolongation (48.5%) had electrolyte abnormalities, 98 (95.1%) were on COVID-19–related QT-prolonging medications, and 62 (60.2%) were on 1–4 additional non-COVID-19–related QT-prolonging drugs. Electrophysiology recommendations were given to limit modifiable risk factors. No patient developed torsades de pointes.

Conclusion

This process functioned efficiently, identified a high percentage of patients with QT prolongation, and led to relevant interventions. Arrhythmias were rare. No patient developed torsades de pointes.

Keywords: COVID-19, QT prolongation, ECG, Hydroxychloroquine, Torsades de pointes

Introduction

The ongoing pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to a number of changes in clinical processes in an effort to provide large numbers of patients with optimal care. Several existing medications are being repurposed for potential prophylaxis or treatment of COVID-19, including chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine1 , 2 often in combination with azithromycin3 and antivirals.4, 5, 6 The use of these medications has been associated with QT prolongation and occasional reports of torsades de pointes when used for their original indications.7 , 8 Their combined use, in the setting of systemic inflammation9 and potential metabolic abnormalities, most specifically hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia,10 seen in the context of this severe systemic illness likely magnifies this risk via multiplicative effects on the rapid delayed rectifier current potassium channel (IKr) as well as other less well-defined mechanisms.12 , 13 Guidance from an American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) position statement14 has supported the use of electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring to identify QT prolongation in patients with COVID-19 being treated with these drugs. We describe the process we instituted to facilitate such monitoring and the outcome of our screening.

Methods

Recognizing the importance of the timely identification of ECG abnormalities, most specifically QT prolongation, in patients being treated for COVID-19, we initiated a hospital-wide protocol designed to optimize ECG monitoring of these patients. This quality improvement initiative was granted an exemption by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. Because patients with COVID-19 are treated by physicians less familiar with the implications of QT prolongation and exacerbating factors such as other QT-prolonging medications and electrolyte abnormalities, our protocol included active involvement of the ECG readers and the electrophysiology team.

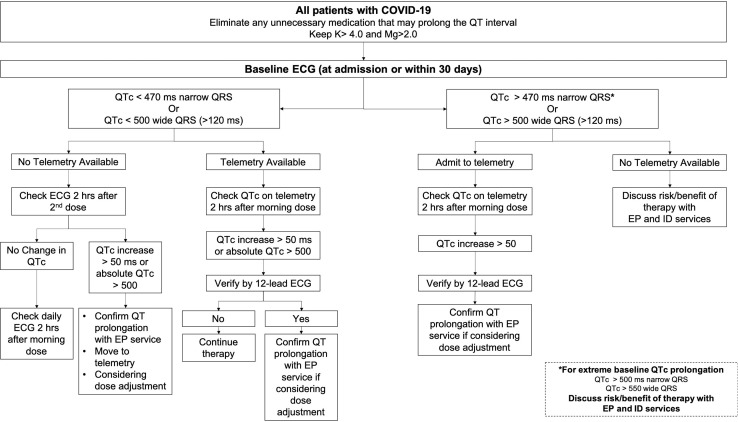

Local hospital stakeholders created an SBAR (Situation Background Assessment Recommendation) tool (Figure 1 ) with guidelines for QT monitoring, which was disseminated to the teams caring for these patients. This SBAR tool tried to balance risk and the desire to limit frequent ECGs in patients with COVID-19 and was largely based on experience with QT-prolonging antiarrhythmic drugs. It did use QT measurements from telemetry when possible, but 12-lead ECGs were used for those not in units with telemetry, a large proportion of patients with COVID-19 at our hospital. We then identified all ECGs from patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 or originating from floors designated as COVID-19 units. Our screening was designed to capture as many COVID-19 patients as possible, and thus a small percentage (65 [15.4%]) of screened patients, often in intensive care units (ICUs) with other medical emergencies, did not have COVID-19. These ECGs were placed at the beginning of the reading queue for the electrophysiologist or cardiologist over reading the ECGs on that day. The daily reader identified all ECGs with significant QT prolongation as outlined in the SBAR tool (corrected QT [QTc] interval > 470 ms for QRS duration ≤ 120 ms or QTc interval > 500 ms for QRS duration > 120 ms) (Figure 1) and notified the electrophysiology consult service, which then reviewed the charts of these patients and provided telephone and, if necessary, formal inpatient support to the primary team caring for patients. This support consisted most often of recommendations to replete electrolytes to more stringent levels (potassium level >4 mmol/L; magnesium level >2 mg/dL) (standard laboratory normals: potassium level 3.3–5.1 mmol/L; magnesium level 1.7–2.4 mg/dL), to discontinue potentially nonessential QT-prolonging drugs as identified by the electrophysiology team, and to consider the risks and benefits of continuing COVID-19 targeted therapy, most commonly with hydroxychloroquine.

Figure 1.

Situation Background Assessment Recommendation tool for the management of QT prolongation in COVID-19 patients. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ECG = electrocardiogram; EP = electrophysiology; ID = infectious disease; QTc = corrected QT.

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical data as number (percentage). P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

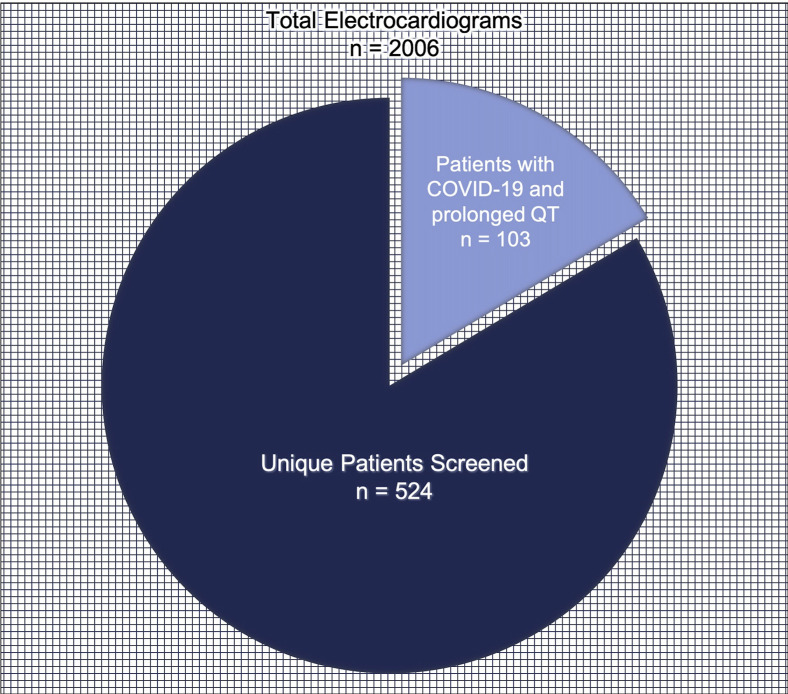

During the 2-week period from March 28, 2020, to April 10, 2020, we identified 2006 ECGs that came from patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 or from a nursing unit designated to care for patients with COVID-19, representing 524 unique patients. Overall, 459 patients (84.6%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of COVID-19. Individual patients had 1–14 ECGs, often over several days. Of these 524 patients, 103 (19.7%), all with a diagnosis of COVID-19, had ECGs with QT prolongation as defined by the SBAR tool (Figure 2 ) and were referred for electrophysiology review and recommendations. Patient sociodemographic and medical characteristics are outlined in Table 1 . Among patients with COVID-19, those with QT prolongation were more likely to spend time in the ICU (60 [58.3%] vs 130 [36.5%]; P < .001) and were more likely to be intubated (32 [31.1%] vs 70 [19.7%]; P = .014) than those without this finding (Table 2 ). Univariate analysis showed that ICU stay and intubation were both associated with QT prolongation (odds ratio [OR] 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–3.8; P < .001 and OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0; P = .015). After controlling for ICU stay, intubation, and tocilizumab and hydroxychloroquine use, multivariate analysis showed that ICU stay was still strongly associated with QT prolongation (OR. 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.7; P = .012) (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Electrocardiograms screened throughout the study period. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of patients with COVID-19 with QT prolongation

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 68.2 ± 15.2 |

| QT interval (ms) | 448.0 ± 44.7 |

| QTc interval (ms) | 507.5 ± 28.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 7.1 |

| Male sex | 64 (62.1) |

| Severity of disease | |

| ICU during hospitalization | 60 (58.3) |

| Intubation during hospitalization | 32 (31.1) |

| Medical comorbidities | |

| HTN | 61 (59.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 50 (48.5) |

| HLD | 33 (32.0) |

| CKD/ESRD | 32 (31.1) |

| AF/AFL | 20 (19.4) |

| CAD | 19 (18.4) |

| Lung disease | 18 (17.5) |

| Morbid obesity | 17 (16.5) |

| Heart failure | 16 (15.5) |

| CVA/TIA | 14 (13.6) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 14 (13.6) |

| Malignancy | 14 (13.6) |

| Cognitive impairment/dementia | 12 (11.7) |

| Cardiovascular implantable electrical devices | 11 (10.7) |

| Liver disease | 9 (8.7) |

| Alcohol abuse/substance abuse | 4 (3.9) |

| HIV/AIDS | 3 (2.9) |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or as n (%).

Malignancy was defined as active cancer or a history of cancer that was treated with chemotherapy.

AF = atrial fibrillation; AFL = atrial flutter; BMI = body mass index; CAD = coronary artery disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; HLD = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; ICU = intensive care unit; QTc = corrected QT; TIA = transient ischemic accident.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of all patients with COVID-19

| QT prolongation |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Present (n = 103) | Not present (n = 356) | |

| Age (y) | 68.2 ± 15.2 | 64.8 ± 17.5 | .137 |

| Male sex | 64 (62.1) | 197 (55.3) | .220 |

| Severity of disease | |||

| ICU during hospitalization | 60 (58.3) | 130 (36.5) | .000 |

| Intubation required during hospitalization | 32 (31.1) | 70 (19.7) | .014 |

| COVID-19–related medications | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 98 (95.1) | 317 (89.0) | .064 |

| Tocilizumab | 83 (80.6) | 223 (62.6) | .001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine + atazanavir | 21 (20.4) | 47 (13.2) | .071 |

| Other COVID-19–related medications | 7 (6.8) | 19 (5.3) | .573 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or as n (%).

Other COVID-19–related medications include remdesivir, nivolumab, ritonavir/lopinavir, ruxolitinib, sarilumab, and plasma.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = intensive care unit.

Among patients with QT prolongation, virtually all 98 (95.1%) were on QT-prolonging drugs related to the treatment of their COVID-19 infection, most commonly hydroxychloroquine (Table 3 ). Of those without QT prolongation, 356 (84.6%) were COVID-19 positive, and of those, 317 (89.0%) received hydroxychloroquine (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Medications and electrolyte abnormalities in patients with COVID-19 and QT prolongation

| Factor | Value |

|---|---|

| Patients with QT-prolonging medications | 103 (100) |

| COVID-19–related medications | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 98 (95.1) |

| Hydroxychloroquine + atazanavir | 21 (20.4) |

| Tocilizumab | 83 (80.6) |

| Methylprednisolone | 28 (27.2) |

| Other COVID-19–related medications | 7 (6.8) |

| Remdesivir | 5 (4.9) |

| Azithromycin | 3 (2.9) |

| Nivolumab | 2 (1.9) |

| Ritonavir/lopinavir | 2 (1.9) |

| Non-COVID-19–related medications | 62 (60.2) |

| Amiodarone | 7 (6.8) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 18 (17.5) |

| Propofol | 16 (15.5) |

| Sedative | 14 (13.6) |

| SSRI | 11 (10.7) |

| Antipsychotic | 9 (8.7) |

| Antidepressant | 7 (6.8) |

| Tacrolimus | 7 (6.8) |

| Antibiotic | 7 (6.8) |

| Antiemetic | 6 (5.8) |

| Other QT-prolonging medications | 10 (9.7) |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | 50 (48.5) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 31 (30.1) |

| Hypokalemia | 27 (26.2) |

| Hypomagnesemia + hypokalemia | 9 (8.7) |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or as n (%).

Hypomagnesemia was defined as a value less than 2.0 mEq/L, and hypokalemia was defined as a value less than 4.0 mEq/L.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

In the group with QT prolongation, the mean QTc interval on the initial ECG was 470.6 ± 35.9 ms, with the peak QTc interval increasing to 520.6 ± 36.7 ms. The QTc interval at the final ECG (which was often the ECG recorded before discharge) showed a mean QTc interval of 478.9 ± 31.1 ms. As shown in Figure 3 , the QTc interval increased significantly and then declined before discharge.

Figure 3.

Box plot of QTc intervals for the initial ECG, peak value, and final ECG. Compared with the initial QTc interval, the QTc interval was significantly longer at peak (470.6 ± 35.9 ms vs 520.6 ± 36.7 ms; P < .001). Compared with the peak QTc interval, there was a significant decrease in QTc interval by the final ECG (520.6 ± 36.7 ms vs 478.9 ± 31.0 ms; P < .001). There was also a difference noted between the initial QTc interval and the final QTc interval (470.6 ± 35.9 ms vs 478.9 ± 31.1 ms; P = .026). ECG = electrocardiogram; QTc = corrected QT.

The electrophysiology consultations identified a number of potentially remediable factors that could also contribute to QT prolongation in patients with this finding, most commonly electrolyte abnormalities in 50 patients (48.5%) and QT-prolonging medications not related to the direct treatment of COVID-19 in 62 patients (60.2%). These patients were found to be receiving up to 4 non-COVID-19–related QT-prolonging drugs, with 38 (36.9%) receiving ≥2 of such drugs, most commonly psychiatric medications, anesthetics, or proton pump inhibitors (Tables 3 and 4 ). While there was a general awareness of the risk of QT prolongation among the treating teams, the consultations frequently identified additional interventions (Table 5 ) and were welcomed by the teams. Specific COVID-19 treatments, most commonly hydroxychloroquine rarely in association with atazanavir or azithromycin, were discontinued in approximately one-third (31 [30.1%]) of patients as a result of QT prolongation at the discretion of the primary and/or infectious disease teams. Despite the relative frequency of significant QT prolongation, serious clinical arrhythmias were rare. No episodes of torsades de pointes were reported. One patient each had ventricular premature complexes and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. One patient had sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in the setting of an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and 3 patients died after being made “do not resuscitate” with comfort measures only. These patients were receiving palliative care and were not being monitored at the time of death.

Table 4.

Other (non-COVID-19–related) QT-prolonging medications in patients with COVID-19 and QT prolongation

| Patients with other QT-prolonging medications |

62 (60.2) |

|---|---|

| No. of medications | Value |

| 1 | 24 (23.3) |

| 2 | 27 (26.2) |

| 3 | 10 (9.7) |

| 4 | 1 (1) |

Values are presented as n (%).

Groups are based on the total number of medications present.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 5.

Electrophysiology service’s additional recommendations made after discussion with the primary team

| Additional recommendations made | Value |

|---|---|

| Magnesium repletion | 25 (24.3) |

| Discontinuing nonessential/use non–QT-prolonging alternative | 18 (17.5) |

| Potassium repletion | 4 (3.9) |

| Continue COVID-19 treatment | 8 (7.8) |

| Telemetry/ECG monitoring | 5 (4.9) |

| Discontinuing antiarrhythmics | 4 (3.9) |

| Continuing antiarrhythmics | 3 (2.9) |

| Dose adjustment | 2 (1.9) |

Values are presented as n (%).

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ECG = electrocardiographic.

Discussion

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused us to modify our usual care pathways to provide the best possible care to the patients, often with suboptimal resources. The medications being used clinically with hopes of improving outcomes in patients infected with COVID-19 carry their own risks. Most notably, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, when used in other situations, carry a risk of QT prolongation and rarely torsades de pointes.7 , 8 While this risk is real, the long history of hydroxychloroquine, and to a lesser extent of azithromycin, use suggests that it is not prohibitive. However, combining these medications in the setting of severe illness, a proinflammatory state, the administration of other QT-prolonging medications and metabolic derangements, most especially hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, has raised concerns about an increased risk of arrhythmia in these patients and have made efficient monitoring and therapeutic adjustments to minimize this risk very important.14 It is also possible that such stresses could unveil previously unidentified monogenetic or other inherited vulnerability to QT prolongation.15 We report here a modification of our usual treatment pathways that we believe has enhanced patient care and may have contributed to a reduced risk of clinically significant arrhythmia while preventing premature discontinuation of potentially effective therapy.

The SBAR tool we used for screening patients was developed at our institution early in our COVID-19 experience and was designed to find a compromise between safety and the need for frequent ECGs before we were routinely using validated telemetry or remote monitoring equipment for measuring the QT interval. It was based on our experience of monitoring patients during antiarrhythmic drug loading, and while it varies in detail from some other published algorithms,16 it shares many similarities. We did identify a high prevalence of QT prolongation 103/524 (19.7%) in our population of screened patients, but it is notable that the majority of patients (72 [69.9%]) were able to complete their therapy, and the only clinically significant arrhythmia seen was in the setting of myocardial infarction. Three patients who were made “do not resuscitate” or “comfort measures only” died in an unmonitored setting. Our patients with QT prolongation had many, often severe, comorbidities. Although we have somewhat less specific clinical data on patients not identified as having QT prolongation on screening, it does appear that those demonstrating this phenomenon were sicker on the basis of ICU admissions and the need for intubation. It would seem likely as well that these situations would increase the risk of polypharmacy and electrolyte abnormalities.

While we think it is likely that many factors contributed to the low incidence of clinical arrhythmias in our patients, we cannot rule out that our interventions, which improved electrolyte management and helped identify other QT-prolonging medications, many of which were then discontinued, played a role in the return of the QTc interval toward baseline values and the low incidence of torsades de pointes. We also hope that they gave support to the treating teams to continue therapy when this was felt to be indicated. We do know that mitigating multiple simultaneous insults to the ion channels involved in myocardial repolarization, most specifically IKr, may be protective.11 Other reasons for the low incidence of torsades de pointes may be the safeguarding effects of relative sinus tachycardia or other unidentified factors.

Although we believe that our process functioned well, we recognized early on that the multiple ECGs recorded in these patients increased both the exposure of caregivers and equipment to infected patients and the use of precious personal protective equipment. Given our finding of a low incidence of clinically significant arrhythmias, we have revised our SBAR tool to reduce the frequency of recommended ECGs and have worked to perform more serial QT measurements using either validated telemetry recordings or remote monitoring in patients in units without telemetry. As such, our report may represent a unique look at ECG-validated QT measurements during the treatment of COVID-19.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations, including those of a single-center retrospective study. During this period, treatment algorithms were evolving and not all patients were treated with a single protocol. Our results are based on ECG measurements of the QTc interval, which, given the desire to limit the use of personal protective equipment and caregiver and equipment exposure to patients with COVID-19 as well as greater comfort with remote monitoring for this complication,17 may be less widely used at this time. In addition, not all patients were continuously monitored and therefore some arrhythmias or transient QT prolongation may not have been identified. However, the lack of significant clinical arrhythmic events suggests that our monitoring protocol, as well as other possible interventions, was fairly effective.

Conclusion

In an effort to provide optimal care in the setting of the current COVID-19 pandemic, we developed a system to rapidly and efficiently review the ECGs of these patients, identify those with QT prolongation, and provide electrophysiological guidance to the treating teams. While we did identify a high prevalence of QT prolongation in this population, we also found a number of modifiable factors including other QT-prolonging drugs that could be eliminated and electrolyte abnormalities that could be corrected. The majority of patients completed COVID-19–specific therapy, and there were no associated episodes of torsades de pointes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristie Lavorgna, Wendy Bruni, BS, and the other staff performing electrocardiography whose hard work and commitment to patient care made this process possible.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.04.047.

Appendix. Supplementary data

2

References

- 1.Zhou D, Dai SM, Tong Q. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression [published online ahead of print March 20, 2020]. J Antimicrob Chemother. 10.1093/jac/dkaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print March 20, 2020]. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 4.Fintelman-Rodrigues N, Sacramento CQ, Lima CR, et al. Atazanavir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [published online ahead of print April 6, 2020]. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.04.020925. [DOI]

- 5.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck B.R., Shin B., Choi Y., Park S., Kang K. Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) through a drug-target interaction deep learning model. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C.Y., Wang F.L., Lin C.C. Chronic hydroxychloroquine use associated with QT prolongation and refractory ventricular arrhythmia. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:173–175. doi: 10.1080/15563650500514558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi Y., Lim H.S., Chung D., Choi J.G., Yoon D. Risk evaluation of azithromycin-induced QT prolongation in real-world practice. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1574806. doi: 10.1155/2018/1574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aromolaran A.S., Srivastava U., Ali A. Interleukin-6 inhibition of hERG underlies risk for acquired long QT in cardiac and systemic inflammation. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang T., Roden D.M. Extracellular potassium modulation of drug block of IKr: implications for torsade de pointes and reverse use-dependence. Circulation. 1996;93:407–411. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson TF, Kovacs RJ, Stecker EC. Ventricular arrhythmia risk due to hydroxychloroquine-azithromycin treatment for COVID-19. American College of Cardiology Web site. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/03/27/14/00/ventricular-arrhythmia-risk-due-to-hydroxychloroquine-azithromycin-treatment-for-covid-19. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 12.Capel R.A., Herring N., Kalla M. Hydroxychloroquine reduces heart rate by modulating the hyperpolarization-activated current If: novel electrophysiological insights and therapeutic potential. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2186–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M., Xie M., Li S. Electrophysiologic studies on the risks and potential mechanism underlying the proarrhythmic nature of azithromycin. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17:434–440. doi: 10.1007/s12012-017-9401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roden DM, Harrington RA, Poppas A, Russo AM. Considerations for drug interactions on QTc in exploratory COVID-19 treatment [published online ahead of print April 14, 2020]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wu C.I., Postema P.G., Arbelo E. SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giudicessi JR, Noseworthy PA, Friedman PA, Ackerman MJ. Urgent guidance for navigating and circumventing the QTc prolonging and torsadogenic potential of possible pharmacotherapies for COVID-19 [published online ahead of print April 7, 2020]. Mayo Clin Proc. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chang D, Saleh M, Gabriels J, et al. Inpatient use of ambulatory telemetry monitors for COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin [published online ahead of print April 18, 2020]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

2