Abstract

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) is experiencing a period of intense progress due to the consolidation of several key technological enablers. AI is already deployed widely and has a high impact on work and daily life activities. The continuation of this process will likely contribute to deep economic and social changes. To realise the tremendous benefits of AI while mitigating undesirable effects will require enlightened responses by many stakeholders. Varying national institutional, economic, political, and cultural conditions will influence how AI will affect convenience, efficiency, personalisation, privacy protection, and surveillance of citizens. Many expect that the winners of the AI development race will dominate the coming decades economically and geopolitically, potentially exacerbating tensions between countries. Moreover, nations are under pressure to protect their citizens and their interests—and even their own political stability—in the face of possible malicious or biased uses of AI. On the one hand, these different stressors and emphases in AI development and deployment among nations risk a fragmentation between world regions that threatens technology evolution and collaboration. On the other hand, some level of differentiation will likely enrich the global AI ecosystem in ways that stimulate innovation and introduce competitive checks and balances through the decentralisation of AI development. International cooperation, typically orchestrated by intergovernmental and non-governmental organisations, private sector initiatives, and by academic researchers, has improved common welfare and avoided undesirable outcomes in other technology areas. Because AI will most likely have more fundamental effects on our lives than other recent technologies, stronger forms of cooperation that address broader policy and governance challenges in addition to regulatory and technological issues may be needed. At a time of great challenges among nations, international policy coordination remains a necessary instrument to tackle the ethical, cultural, economic, and political repercussions of AI. We propose to advance the emerging concept of technology diplomacy to facilitate the global alignment of AI policy and governance and create a vibrant AI innovation system. We argue that the prevention of malicious uses of AI and the enhancement of human welfare create strong common interests across jurisdictions that require sustained efforts to develop better, mutually beneficial approaches. We hope that new technology diplomacy will facilitate the dialogues necessary to help all interested parties develop a shared understanding and coordinate efforts to utilise AI for the benefit of humanity, a task whose difficulty should not be underestimated.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Human well-being, Decentralisation, Protectionism, Techno-nationalism, Fragmentation, Technology diplomacy, International collaborative governance

Highlights

-

•

AI requires enlightened responses by stakeholders to realise its tremendous benefits while reducing undesirable effects.

-

•

AI deployment among nations risk a fragmentation between world regions that threatens technology evolution and collaboration.

-

•

AI needs international cooperation to address policy and governance in addition to regulatory and technological challenges.

-

•

The emerging concept of technology diplomacy will ease global alignment of AI governance and a vibrant innovation system.

1. A new, international game changer

The confluence of several enablers is greatly advancing artificial intelligence (AI). They include: (i) the exponential growth of available data to train learning machines; (ii) more powerful computer-processing capabilities, which can be used in deep neural networks and other learning techniques; (iii) advances in algorithms that greatly increase the effectiveness of machines to solve a variety of problems across industries; (iv) the decades-long accumulation of software in general as a cultural-technological heritage; and (v) the rapid cost decreases and hence widespread availability of complementary technologies, such as ubiquitous connectivity, ubiquitous computing, and the internet of things (IoT).

Although technology has not yet succeeded in creating “strong” AI that is functionally equivalent to a human's intellectual capabilities, increasingly capable versions of “weak” AI that are focused on narrow tasks have become very powerful. Consequently, AI is increasingly embedded in business and daily life processes, and AI-driven tasks are reshaping businesses, markets, and industries. Experts and analysts compare this process to a new industrial revolution in terms of its capacity to change economy and society. AI is poised to transform not only how we think about productivity or our relationship with our environment, but also elements of national power. Just as past industrial revolutions have increased the power and influence of nations that used technology more widely, AI has the potential to become a similar game changer at the international level.

In fact, international competition has already begun. A full-fledged race for AI breakthrough technology is underway among the United States, China, and more recently, the European Union (EU) and other countries, such as Korea, Japan, Russia, and India (see the papers in this special issue). It is widely expected that the winners will dominate the coming decades economically and geopolitically (Bremmer & Kupchan, 2018). A high-level assessment shows that the United States and, to a lesser extent, the EU have advantageous positions in research and innovation capacity, but that China is benefitting from its head start in applications and business-to-consumer use cases (Craglia et al., 2018).

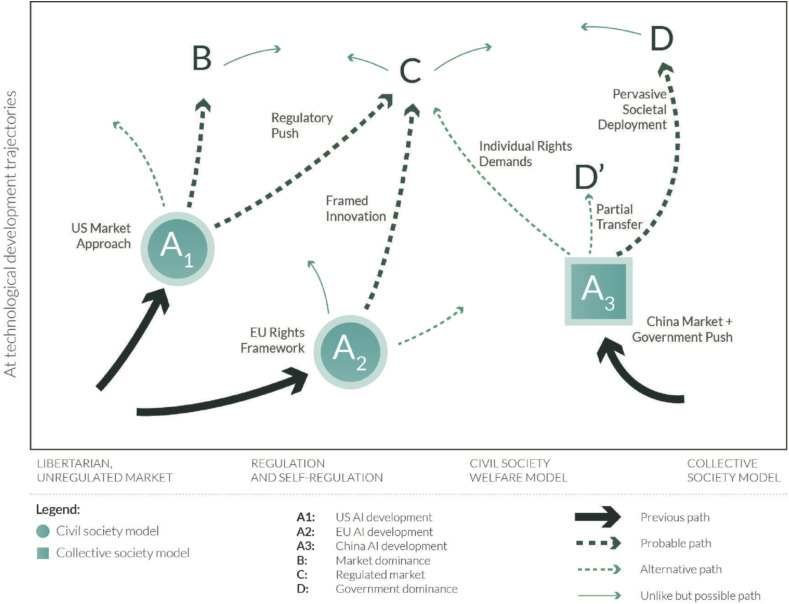

In a highly stylised fashion, Fig. 1 below illustrates different policy paths for China, the EU, and the United States in the competition to lead AI developments. The solid arrows symbolise each region's historical path towards its present combination of market and regulatory actions: A1 gives pre-eminence to technology development via market forces, whereas regulation is the predominant driver along the path leading to A2. Both the market-driven and regulation-driven paths allow multiple continuing trajectories. They lead to several possible combinations of technology development and society welfare. Two likely more steady states are represented by areas B and C. State B encompasses technical and institutional arrangements in which free markets solutions prevail. State C includes approaches that embrace strong regulation of AI with the goal to strengthen welfare in a civil society framework. From the present status quo of A1 and A2, not all developments are equally likely (represented by different line thickness). For example, the market-based model of A1 could evolve toward less regulation, even though this is unlikely. Alternatively, A1 could continue to exist as a market-based option (state B in Fig. 1) or it might develop into a more strongly regulated model (state C). A2 will most likely evolve toward C, even though there is a slim chance that it might migrate toward B or D (see below).

Fig. 1.

AI policy paths in the EU, United States, and China (as of 2020). Source: Own elaboration.

A key distinction from previous, technological developments is China's new role. Its AI plan leverages the momentum provided by the government and private companies to move beyond the outcome that the market alone could provide (with or without regulation). This is represented by A3, which differs from the combinations of market forces and regulation that lead AI development in the EU and the United States. China has been able to mobilise resources for AI that combine a long-term vision of technological development that is independent of the policy cycle and builds on a different set of societal values (represented in the figure by a square). Similar approaches are not available in democracies because of limits on government power and popular mandates from the electorate that do not allow comparable discretionary state action, but rather build on a civil society set of values (represented in the figure by circles).

From A3 in Fig. 1, there are three alternative continuing paths. The first track leads back to C, possibly because of strong demand for individual rights by the public. This would eventually constrain China's technologically driven AI ambitions. The second track is an intermediate and probably unstable situation depicted in D′, where there are more advanced technological deployments, but they are not fully translated into societal advantages. The third track - advanced technology – is probably most aligned with China's present vision for AI. It opens the door to a new type of society, in which AI is used to advance collective societal goals, even if those come at the expense of individual rights, a “brave new world” (state D). It is important to stress that B, C and D are not definite scenarios. Rather, they represent a continuum of options for the countries and regions depicted in Fig. 1 and for other countries looking to chart their own AI development path. In fact, it is too early to tell which of these steady states will be pursued, whether multiple models will coexist, or whether convergence to one or two models might occur. Moreover, it is too early to evaluate fully the strengths and weaknesses of the alternative models and their repercussions for wellbeing.

Chinese policy making gives high priority to both (national) social and economic development. The overall ambition is to achieve the goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is for China to catch up and eventually surpass Western industrialised countries. The approach to policy making is radically practical; several different strategies are tested in pilot projects. Depending on the outcomes of these pilot tests, policies are either abandoned, refined, or rolled out across the country (Stepan & Duckett, 2018). Experts and political scientists have coined terms, such as “techno-socialism,” to describe the Chinese government's strategy to exploit technologies, including AI and big data, to boost development in a framework of social control (Fischer, 2018). Of course, an interesting question is whether this new model will stay confined to China or will migrate to other geographies, possibly inducing market economies to lean toward more authoritarian approaches.

Summarizing this international competitive dynamic, some experts note that “… AI-induced disruptions to the political and economic order will lead to a major shift in how all countries experience the phenomenon of digital globalisation” (Lee, 2018). Moreover, it is no longer possible to assume that technology automatically results in social progress. For example, data from the United States and EU countries suggest that, in general, material conditions have improved much more than the quality of life perceived by citizens or society at large (OECD, 2017). This is akin to a “saturation effect” in which increased income does not contribute to a proportional increase in happiness. Thus, AI has the potential both to increase wellbeing and to undermine it.

This article examines the rationales for the increasing competition in AI between countries and jurisdictions. It investigates potential measures to relieve the tensions associated with growing competition in AI development and to enhance the diversity and complementarity of the global AI innovation ecology. To attain these goals, the next section discusses the differences in the development of AI across jurisdictions. The following section three offers a brief sketch of the emerging international struggles between the major players in AI development. Section four further describes three stages of the ongoing process of international competition: (i) techno-nationalism, (ii) protectionism, and (iii) fragmentation. We argue that important global players have already moved into the second of these stages in 2020 and are approaching the third stage. Possible social and economic disruptions are presented briefly in section five. The final two sections discuss the status of cooperation in AI and outline the main contours of a new technology diplomacy designed to complement and integrate the numerous other efforts intended to develop AI that serves the common good.

2. Compartmented innovation ecosystems

A first observation is that AI innovation ecosystems are developing relatively independently of each other in different countries and regions. Some connections exist between researchers at universities and research centres in different countries. Major technology companies also have set up basic research centres and funding in other locations, often with the goal to tap local talent and benefit from local developments (see the paper by Righi, Samoili, López et al., in this issue). Presently, there are no AI standardisation initiatives comparable to other domains, such as mobile communications. This is possibly because the two technological and economic hegemonic powers are far ahead of other countries and feel no need to form alliances. For instance, the foreign presence in the AI ecosystem in China is low, although there are some minor exceptions through above-mentioned company research centres, university collaboration, and individuals working in start-ups and venture capital (Feijóo et al., 2019).

The hardware and software that is driving most AI developments is dominated by US companies, such as Qualcomm and Nvidia in chips and Google's TensorFlow software. To reduce this dependence and especially since the US ban on certain high-tech exports (whether it is upheld or not), the main Chinese tech companies (Baidu, Huawei, Alibaba) have accelerated plans within the Made in China 2025 policy to build their own AI chipsets. Much of the software, including TensorFlow, is open source and therefore fully available to anyone who wishes to use it. Nevertheless, considerable influence remains with organisations that fund software development and the community that coordinates projects that make use of any given open-source, software version.

It is generally acknowledged that the EU leads in terms of the number of experts in AI, followed closely by the United States and, at some distance, China (Ng, 2018). The EU and United States lead not only in terms of the absolute number of experts but also in their level of expertise. Here, universities are supposed to be the engines to produce human capital, not only by training new scientific and technological talent, but also by conducting basic research. However, it is less clear that this lead extends to university rankings where China is closing the gap. Nor is it clear that it extends to the cultivation of relevant business and managerial expertise, where China may have an advantage by dint of its greater deployment rate. As countries move beyond a focus on growing the number of individuals with post-graduate education, improving the quality of student education and training are emerging as arenas for AI competition (Zhang, 2018).

Differences across jurisdictions also reflect user behaviour and culture, government policies and supports, and the level of private-public partnerships. There are three reasons for China's success in business-to-consumer AI implementations. They are the swift adoption of applications by users who generally embrace technological novelties; that the government favours national security, stability, a positive impact on social welfare, and a strict control of cyberspace (Puig, Dai, & Melo, 2014) over privacy and individual rights; and that China's large companies are particularly supportive of this collaboration with the government (Zhong, 2018). A combination of large state subsidies, government research and development (R&D) funding, tailored regulations, market entry barriers, lax protection of individual rights (e.g., in the area of privacy), localisation, and rapid technology adoption by consumers provide the Chinese AI market and domestic companies an edge over foreign competitors (see the paper by Arenal et al. in this issue).

An additional key difference is related to responses to the large-scale implementation of AI solutions. Outside China, this has triggered an intense debate about privacy and abuses arising from algorithmic decisions. Critical views in the EU and the United States are on the rise. The European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is one main, practical outcome of these concerns (European Commision, 2016; World Economic Forum, 2018a). Generally, the United States is more favourable to self-regulation by companies and voluntary codes of conduct. In the wake of increasing concerns about their power, leading tech companies have indicated a willingness to accept external, if only partial, regulation. These proposals are arguably motivated by endeavors to protect existing market positions from both local and (especially) international competition. In China, public criticism of the privacy risks of AI refers only to the usage of companies and never of governmental bodies, because the latter could be interpreted as lack of loyalty to a policy highly supportive of AI developments. AI experts based in China claim that the country is catching up and is paying increasing attention to ethics, at least in specific domains, as evidenced by a recent draft proposal for AI ethics guidelines. The most prominent examples cited are AI ethics regarding driverless cars and robots, although there is also some concern about AI in general or data ownership liability. It is worth noting that presently the practice of ethical review for research programs—government-sponsored or privately-funded—remains elusive in China. This can sometimes be disturbing when it comes to potentially negative consequences of the deployment of some high-tech developments or innovations. In effect, China's scientific, industrial, and political institutions have yet to meaningfully embrace the notion of technology ethics. Another major argument discussed in China is the strong focus on solving specialised problems at the expense of concerns about the societal implications of AI. In the long run, this could lead to considerable contradictions between the benefits for specific application areas and the overall effects of AI on society.

In summary, the calls for policy support voiced in the EU and the United States focus on algorithmic transparency and accountability (Garfinkel, Matthews, Shapiro, & Smith, 2017) and warn about the outsourcing of moral responsibilities to algorithms. In contrast, the focus in China is more on placing AI within the scope of the rule of law (People’s Daily, 2018; Tan, 2018), even if the pervasive usage of AI in China has highlighted that the absence of a more forward-looking perspective could lead to a lack of verifiable algorithms or trustworthy devices and systems. Across all jurisdictions, research into AI engineering and technology perspectives continues to dominate. Social scientists, primarily in business, economics, and the humanities contribute a comparatively low number of papers (Shoham et al., 2018).

Military and defence involvement are another salient feature of the AI innovation ecosystem in many countries. Many AI breakthroughs have dual use and can be put to civilian and military uses. China's People's Liberation Army considers modern warfare as “systems confrontation … waged not only in the traditional physical domains of land, sea, and air, but also in outer space, nonphysical cyberspace, electromagnetic, and even psychological domains” (Engstrom, 2018). To this end, AI could speed up military transformation by means of intelligent and autonomous unmanned systems. It could provide AI-enabled intelligence analysis, war-gaming, simulation, and training; defence, offence, and command in information warfare; and intelligent support for command decision-making (Kania, 2017). Of course, the different strategies enacted by countries reflect their capacity to shape the international governance of cyberspace according to their own interests (Godement et al., 2018).

3. International spillovers: Heading for data and service colonialism?

The logic of internationalisation, which has been evident over many years in the global expansion of physical infrastructures, markets, cultures, and ideologies, is also visible in information and communication technologies (ICTs). Major providers of AI solutions are extending their international reach mostly through cloud computing solutions. Resources to process data for AI services are available in this cloud, also referred to as AI-as-a-service (AIaaS). Emerging 5G wireless communications are also considered to be a technology that supports these deployments. The “cloud strategy” for AI provision is a favoured business model. High, upfront, fixed costs of AI in combination with economies of scale and scope in development and operation make AIaaS more economically attractive than proprietary AI (see the paper by Wagner in this issue).

By generalizing Simón and Speck’s (2017) ideas to any geography, a scenario could unfold in which small countries are using existing foreign investments in infrastructures, transport, telecommunications, and utilities and exchanging data for services or ICT infrastructures. This could eventually create a new form of dependence between countries with leading AI companies and those without such capacity, in a process combining aspects of digital imperialism and digital colonialism (Couldry & Mejias, 2019; Jin, 2015). Furthermore, any governments especially worried about potential social unrest within their borders may find ways to use technology and particularly AI for control and surveillance to achieve enforced social harmony and stability (Griffiths, 2018).

Following the logic of this scenario, in mid-2018, China started to promote a so-called digital Silk Road, an extension of the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). This included 5G, quantum computing, nanotechnology, AI, big data, and cloud computing and was helping other countries to build digital infrastructures and develop Internet security. According to the Chinese government, it will help to build “a community of common destiny in cyberspace” (“A web of silk,” 2018). The goals of such an initiative would be to “create export markets for Chinese technology; establish a bigger base for Chinese technological development through access to data; provide physical infrastructure for the BRI; and boost goodwill towards China in beneficiary markets” (Gold, 2018). In addition, the BRI has tended to be interpreted more from economic and trade perspectives than through a political, if not ideological, lens, which can hinder the full grasp of the actual scenarios. The extent to which markets have been opened for Chinese technology can be gauged by the extent to which technologies, such as facial recognition, are being sold to relatively impoverished African nations, such as Zambia and Uganda.1

The United States and the EU have no defined initiative comparable to the BRI to extend their technological influence globally. The creation of international spillovers were left to private companies with some support from public, foreign affairs, and international trade policies. This approach has further fragmented the policies of nations that have historically been close allies so that their focus is on companies and not countries. For example, Australia, a long-time trade and military ally of the United States and the EU, is moving to implement discretionary taxes on companies, such as Google and Facebook, at the same time that it has banned the deployment of Huawei equipment in its 5G infrastructure. Given the fragmented response to the BRI, the EU has started to compensate for and/or collaborate in these developments with the launch of the first EU-China investment fund in July 2018. The fund is backed by the European Investment Fund as well as other Chinese and European institutional and private investors. However, the fund targets only those mid-cap companies with high growth potential in Europe and China, in areas such as healthcare, high-end industries, consumer goods and business services. In fact, experts agree that more public investment in AI and robotics is needed to maintain EU competitiveness. The EU need is likely to be compounded by challenges to cooperation with its traditional partner, the United States (Marcus, Petropoulos, & Yeung, 2019).

4. The risk of inefficient fragmentation

The pursuit of diverse approaches to exploit AI can increase the number of experiments and hence accelerate the process of trial and error that drives innovation (McAfee & Brynjolfsson, 2017). However, because many AI applications also need coordination to realise their full potential, there is likely a non-linear relationship between diversity and innovation. To some extent, diversity and innovation complement each other, but if the ability to learn from diversity is reduced, innovation may suffer. Techno-nationalism, protectionism, and dysfunctional fragmentation are all scenarios that potentially undermine this innovation dynamic and threaten the realisation of the full benefits of AI. Thus, it will be important to prevent the sector from fragmenting to an extent at which complementary innovation slows. However, some level of diversity and fragmentation are acceptable if they support innovation.

4.1. Techno-nationalism

China is leading the investment in markets based on new technologies, particularly AI. In 2017, it was responsible for 48% of all investments going to AI start-ups globally, surpassing the United States for the first time (CBInsights, 2018). In Western countries, these markets are typically led by the private sector with some support from public bodies. However, as explained above and stated by Bremmer and Kupchan (2018), in the case of AI, “in China the leadership comes from the state, which aligns with the country's most powerful companies and institutions, and works to ensure the population is more in tune with what the state wants.” This policy makes it difficult for foreign companies to participate in the markets of most of China's high-tech sectors. The general opinion held by experts at foreign companies is that innovation-related markets in China are still closed. Therefore, there is still a major clash between the objectives of opening the market and collaboration on the one hand, and China becoming technology independent on the other hand (Fabre, 2018). Over the past decade, China has been engaging in so-called “market for technology” swaps when dealing with foreign direct investment, a practice now officially termed by the United States as “forced technology transfer.” Again, experts disagree on future developments, and opinions range from further opening through enhanced IP framework protection and the promotion of collaboration, to more barriers.2 These barriers might be lower in service sectors, such as healthcare or mature manufacturing industries. However, so far, no foreign companies have made any major inroads in the case of AI. These include domains where there are not cutting-edge Chinese companies, such as enterprise AI, or recruitment.3 At the same time, historical issues, such as IP protection, appear not to be a relevant concern with respect to the development of the AI industry in several subdomains, in which China is a leading force, and foreign companies have set up research centres in China to tap into local talent.

This perception that there is no friction-free, international collaboration in AI has two main effects. First, solutions are developed independently and may only be valid inside a country because they do not meet or conform to international/other jurisdiction standards. Second, there is a permanent temptation in other jurisdictions to retaliate with protectionism to compensate for the lack of opportunities in the closed market. Retaliation is also likely where foreign-controlled AI applications result in apparent extraction of wealth from other jurisdictions, e.g., Australia's intended tax on online platform firms discussed above. In other words, as barriers are erected, the incentives for openness and collaboration are eroded, resulting in ever more fragmentation.

However, there is another and potentially even more important factor. As discussed, AI is a technology with outstanding security and defence applications. Nations are under pressure to protect their citizens, their interests at home and abroad, and their own political stability in the face of possible malicious or fraudulent uses of AI. Thus, the grounds for an argument in favour of techno-nationalism are already present and rapidly gaining more support. It could take the shape of explicit and strict conditions on the participation in market development, such as server location, involvement of local companies and access to users’ data, or implicit policies and behaviours that ultimately lead to a closed market, or a combination of both. In any case, China already has a clear head start in the establishment of control mechanisms for policy-based market configuration. We also conjecture that the countries with the capacity to build AI systems by themselves are also behaving similarly in the policy domain, although all of them deny that this is the case.

4.2. Protectionism

Apart from techno-nationalism, protectionism is an additional factor that increases the chances of a general outcome in favour of undesirable fragmentation. On one side, there is a growing reluctance among foreign companies to use Chinese technology due to the above-mentioned asymmetries in the regulatory treatment of firms across jurisdictions and the difficulties in getting access to the Chinese market. On the other side, the increasing amount of Chinese investment abroad4 in both infrastructures and cutting-edge technology companies, which have captured some key intellectual property, has led EU and US institutions to rethink existing mechanisms for the supervision of foreign investment in key sectors and the consideration of safeguards for technologies regarded as crucial for national competitiveness. Using a range of economic and national security arguments, some governments have vetoed the participation of foreign companies in activities that they consider critical.

A central source of these concerns is the direct or indirect involvement of China's government in investments and the implications of this involvement for access to dual-usage (civil and military) technology and the resulting political and economic influence that may arise. Although it is tempting to focus on specific cases and technologies, the broader picture may be overshadowed. The tensions between China and other countries in this area are as much about China's emerging role at the centre of the world economy and the struggle for hegemony between the United States and China as it is about the specific technology in question.

A major example of this growing wave of protectionism is the increasingly touchy relationships between governments and vendors of telecommunications equipment, including hardware and software, cloud provision and cybersecurity,5 as well as the launch of, or threat to launch, new taxes on imports6 from both the United States7 and China. Recently, this tendency is aptly illustrated by the banning or attempts to ban the use of Zoom, a synchronous meeting or teaching, web-based software and whose popularity dramatically increased due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Some commentators argued that the software possessed security flaws, was developed in China, and that one of its data centres is in China. Despite the security patches and the changes in the flows of information of this software for non-China users, the debates illustrated how arguments for protectionism are already well-entrenched in many societies.

According to Bremmer and Kupchan (2018), this new protectionism may take the form of bailouts, subsidies, and “buy local” requirements designed to bolster domestic companies and industries. They do not necessarily circumvent World Trade Organisation (WTO) commitments that have already been weakened by actions taken by the current US administration, but rather exploit the current inability to update and strengthen existing global trade rules. In fact, according to the European Commission, China already has the second highest number of active trade barriers, including both behind the border and at the border measures (European Commission, 2017). Other countries may soon enact their own barriers, further restricting the flow of goods and services globally.

4.3. Fragmentation

Excessive fragmentation of the tech commons8 is potentially the major, ultimate effect of techno-nationalism, protectionism, and the global tech competition. In fact, China's internet users already see a different applications-and-services picture than those in the EU and United States.9 This differentiation started as a result of the Great Firewall. Now, however, Chinese providers have grown large and innovative enough to inhabit most of the available market space. Little if any room would be left for foreign products and services, even if the restrictions were to be lifted.10

5G networks are becoming or might become an example of this possible fragmentation of technology with “politically divided and potentially noninteroperable technology spheres of influence” (Triolo, Allison, & Brown, 2018). One sphere would be led by the United States and supported by technology developed in Silicon Valley, and another led by China and supported by its cadre of highly capable, digital platform companies. Outside of these two camps and arguably caught between them would be several other spheres - the EU, Korea, Japan - that possess some form of 5G industry and 5G-related innovation capabilities. The paper by Taylor on quantum computing in this issue revolves around the competition between the United States and China.

Fragmentation will create a much messier technology evolution (Bremmer & Kupchan, 2018) with less competition, oligopolistic market structures in different territories, and the solidification of the influence of state decisions. Perhaps the best example of the consequences of fragmentation is global cybersecurity, where the incentives for aligned and cooperative research and protection across different geographies could well disappear. In addition, access for companies and users to supply chains would be more complicated, and they would face more restrictions to data flows and other barely discernible or invisible barriers. Generally, the opportunities for doing business would decrease, and collaboration across jurisdictions would be less reliable and fraught with challenges and obstacles. Countries would face the difficult choice between using technology from foreign (potentially hostile) owners and risking a go-it-alone strategy under which they might fail to develop technologies themselves that were adequate for use by the business sector or in defence. This is discussed in more detail in the following section.

Not all technological or economic fragmentation is inefficient or undesirable. Diversity in AI technology development inevitably entails some level of fragmentation and might not be necessarily and always be associated with reduced welfare. Fully integrated and globally interdependent systems are often highly vulnerable, as we can see in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Some degree of fragmentation, in the sense of diversity, can increase the overall performance and resilience of global innovation systems and business and social communities. Appropriate interoperability provisions can mitigate concerns about fragmentation. They are further eased if efficient converter technology is available (e.g., Gottinger, 2003). Thus, a key to national and international AI policy must be to keep the system within the boundaries of a functional level of diversity.

5. International social and economic disruptions

The main effects of infrastructural technologies, such as AI, materialise at the sectoral and macroeconomic levels rather than at the level of individual companies. In the future, if a country lags in its deployment of AI technology, its industry as a whole will face difficulties, potentially compromising the country's overall competitive position.11 Echoing this concern, Kai-Fu Lee, a leading expert on AI, argues that AI will create a divide between countries.12 Those countries that have AI technology will be much better off and will be able to create new value if AI is used as a means to improve rather than undermine the wellbeing of citizens. Also, countries that have large populations that allow the gathering and iteration of large volumes of data through the AI algorithm will enjoy a competitive advantage.13 In contrast, countries with a large population but without technology run the danger of becoming data points in the algorithms of other country's companies. This has been termed “data colonialism” (Harari, 2019). Moreover, the competitive advantage of low-cost labour that propelled countries such as China to increase their income levels will no longer be an option for others because AI and robots will eventually do most of the routine work (Frey, 2019). Worse still, the AI-induced transformation is expected to happen at a much faster pace than any previous industrial revolution.

The combination of AI and demographics and its potential consequences of unequal job distribution and economic disruption could reshape the relationships between citizens, governments, and markets and have far-reaching implications for countries. A study by Bain on the impact of AI on jobs estimates that AI and robots may eliminate 20%–25% of current jobs in the United States by the end of the 2020s, hitting middle-to low-income workers the hardest (Harris, Kimson, & Schwedel, 2018). A study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) states that the share of jobs at potential risk of automation by 2020 is only 1% across twenty-nine analysed countries (Baccala et al., 2018, p. 2018). The World Economic Forum (2018b) examined the division of labour between humans and machines in large companies in twelve industries. The study concluded that the share in total task hours performed by machines would increase from 29% in 2018 to 52% in 2025. The same report argues that if the workers at risk of losing their jobs to automation are “given significant reskilling, and a pipeline of new workers is created in schools and colleges,” companies could create more new jobs than will vanish. According to McKinsey's estimates, in the case of China, 100 million workers would need to switch occupations if automation is rapidly adopted. This would be equivalent to 12% of the 2030 workforce. In any case, a significant part of the jobs at risk are in conventional industries, which still rely on public subsidies, adding pressure to and complicating the transformation. One can therefore easily imagine that political pressures might incentivise further fragmentation as an expedient tool for medium-term protection of employment. Economies that control the technologies and are skilled users will, however, be in a better position to steer the process, if required. They might delay the introduction of certain technologies through regulation while retaining the advantage of being an exporter and in control of the technological know-how.

Thus, there is fierce competition for talent14 and a race to attract and locate major AI companies and start-ups to compensate for the job losses and establish the conditions for renewed economic growth. Only countries in which a large enough percentage of the population can create value will be able to escape having to depend on today's leading countries. As a consequence, an argument has emerged that this competition may lead to increased conflict, possibly to some sort of economic or other war.15 This can be tentatively observed in the discussion about whether limits should be placed on where foreign, highly-skilled labour can work within a country's AI ecosystem.16 Recent limitations on the physical movement of people across national boundaries invoked by Covid-19 illustrate how fragmented, protectionist policies will exacerbate the effects of displacement by preventing the free movement of skills and labour.

No review of the developments of AI and its economic effects would be complete without mentioning the growing alarm surrounding the potential future, but also present, dangers of AI for society (Parnas, 2017). In fact, there is a real danger that a new arms race in the field of AI technologies could develop (Karelov, Karliuk, Kolonin, Markotkin, & Scheftelowitsch, 2018). It is notable that the regulation of the development of AI technologies, which can have wide repercussions for society and can potentially be weaponised, is not contemplated in international law although other technologies with far-reaching impact are regulated by international agreements and conventions. At the same time, the model of international treaties or laws might not be useful to govern malicious AI, which is much easier to develop and can be used by almost anyone or any organisation.

There are multiple concerns about the potential harmful uses of AI. There is a concern that AI could eventually make people superfluous,17 or that AI could be used by regimes to target certain parts of their population. There is a concern that AI will be employed to expand cyberattacks and augment the threat of physical attacks, that AI will be applied to increasingly invade an individual's privacy, and that social manipulation through surveillance, persuasion, and deception will occur. And there are concerns regarding the application of AI methods to develop devices and systems that are untrustworthy and dangerous. Finally, the combining of AI with other technologies, such as robotics, to create lethal automatic weapons (LAWS) is alarming (see the paper by Gómez-de-Ágreda in this issue).

In any case, AI, digital, physical, and political security are deeply connected and are likely to become even more so. Even at its current capability levels, AI can be used in the cyber domain to augment attacks on and in the defence of cyberinfrastructure. Its introduction into society changes the scope and scale of the attack that hackers can mount. All of these concerns are most significant in the context of authoritarian states, but may also undermine the ability of democracies to sustain truthful, public debates (Brundage et al., 2018).

6. International perspectives on the regulation of AI

A direct consequence of the potentially malicious usages of AI is the discussion of whether AI should be regulated now or in the near future, and, if so, whether effective regulation is even possible (see the paper by Robles in this issue). Given the pervasive implications, the principles of when it might be reasonable to regulate AI and which instruments to use are in flux. In a provocative note, Harari (2019) suggested that countries that have fallen behind in AI have only two options: to join the race and possibly develop niche AI or to regulate the uses of AI to mitigate potentially undesirable uses. In the United States, China and the EU, initiatives exist to regulate AI, but each country takes a different path.

In 2017, the US Congress proposed the FUTURE of Artificial Intelligence Act, which made provisions for an advisory committee to examine the impacts of emerging AI technologies on many aspects of life and develop proposals to address emerging concerns.18 This could include policies related to the workforce, privacy, innovation, and “the development and application of unbiased AI” (Beishon, 2018). Although not strictly a regulatory body, such a committee would likely have significant oversight powers. In addition, there are moves by market players towards some type of self-regulation.19 This was recently reshaped in calls for external, partial regulation and calls in the United Kingdom for the industry to establish a voluntary mechanism to inform consumers when AI is being used to make significant or sensitive decisions (House of Lords - Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence, 2018). To date, however, these have yielded little more than codes of conduct overseen by third parties, which may be government bodies. A different approach would be to have an AI ethical commitment similar to the Hippocratic Oath sworn by doctors.20 However, such oaths are not binding and, unless enforced by way of regulatory or membership bodies, are likely to be prone to free-riding or non-compliance.

China has also launched several initiatives that focus on ethics-related standardisation primarily with involving driverless cars and robotics. Industries with support from government bodies typically lead these initiatives. In cities such as Shanghai and Beijing, there are even some steps to allow people to dispute incorrect information to compile social-credit records while, for instance, using the metro or crossing streets. In June 2019, China issued its first AI ethics code, the so-called Beijing AI principles (Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence, 2019), which are similar to others except for the preference given to society vis-à-vis individuals. Although the possible impact of the principles in areas such as privacy or individual freedoms is still unclear (concepts are usually interpreted differently in China than in Western countries), they are a first signal of some willingness within the country to discuss the ethics of AI. All in all, the general status of the rule of law remains an undergirding consideration.

In December 2017, the EU declared the need for a high level of data protection, digital rights, and ethical standards in AI and robotics (European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies, 2018). The European Commission Communication on AI insists on ethical standards as well as preparedness for the social changes caused by AI (European Commission, 2018). There are also calls to implement key ethical principles in AI, such as beneficence, non-maleficence, the power to decide, justice and explicability (Floridi et al., 2018). The EU's high-level, expert group on AI also reached the same conclusions about trustworthy AI and recommended human oversight, a fall-back plan, privacy, traceability, non-discrimination, and accountability (High-level Expert Group on AI, 2019). For additional details on Europe, see the paper by Vesnic-Alujevic, Nascimento, and Pólvora in this issue.

France's President Emmanuel Macron has launched the idea of three main, regulatory challenges for AI: analysis and control of significant market power; compensation for negative externalities resulting from industries that are digital rather than territorially based; and a re-examination of privacy in the context of democracy, accountability, and sovereignty.21 President Macron has also proposed that the algorithms used by the French State be made public (Ma, 2018).

The House of Lords in the United Kingdom has also called for safeguards against the monopolisation of data by large companies (House of Lords - Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence, 2018). In fact, whereas the government and companies in China take a united approach towards sovereignty, large companies in the EU and the United States challenge the provision of safety that lies in the very fabric of the social contract between citizens and states. This is particularly difficult, given that virtually all AI models necessarily include a “black box” aspect to the software that even the creators do not fully understand. However, it could be very helpful if authorities could specify a clear set of safety tests for AI applications in specific areas, not only to protect the public but also to help companies by certifying these products. Alternatively, regulators could require AI deployments in certain areas to specify clearly which safety tests have been conducted. This could be similar to the process for drug certification, which is an analogy that cautions against the possible imposition of unreasonable or inefficient costs on the industry.

Another major regulatory challenge in the realm of AI is preserving algorithm openness so that they can be checked for transparency and potential bias.22 This imperative is possibly in conflict with intellectual property arrangements, in which firms might prefer to keep methods confidential, e.g., for image or voice recognition, and where these methods give them a clear competitive advantage. Openness can be guaranteed for patented inventions. However, this approach presents many problems of its own because the use of software methods is difficult to patrol, and jurisdictions vary widely regarding the extent to which software methods can be patented. In addition, the EU has argued for free and fair international trade (European Commission, 2017).23

7. The need for a new technology diplomacy and collaborative governance

The large variations in political, strategic, and ethical perspectives and policies on the envisioned lawful and unlawful usage of AI among China, the United States, the EU, and other main countries, such as India, Japan, Korea or Russia, risk undermining the potential of AI to advance the common good. Many discussions among a wide variety of stakeholders are already under way on how to harness the power of AI while addressing potentially negative effects on global wellbeing. Many initiatives have emerged driven by the civic, non-profit, for-profit, and government players involved in internet governance, computing, technology policy, and multilateral organisations. These include several United Nations organisations, the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Open AI, Data Pop Alliance, and AI Now Institute, to name some of the more salient initiatives (Butcher & Beridze, 2019). In addition, countless conferences and workshops by academic and professional organisations, intergovernmental organisations, non-governmental governance organisations, civil society groups, as well as industry and consulting events now regularly address artificial intelligence issues.

However, many of these important initiatives and conversations are confined to single countries, sectors, or issues. For instance, the EU has launched a set of initiatives on the ethical aspects of AI to maintain a balance between data-informed surveillance and democracy. This is viewed in the EU as part of a process towards a common, internationally recognised, ethical, and legal framework for the design, production, use, and governance of AI, robotics, and “autonomous” systems (Philbeck, Davis, & Larsen, 2018). An additional position in the EU aims to avoid the full transfer of power from individuals to either governments or private companies. 24

These initiatives are important and welcome as initial steps in a broader process to discuss and shape AI for human benefits. Like other information technologies, AI can be envisioned as a multi-layer system with technological, organisational, and societal layers that interact in bottom-up and top-down processes (e.g., Gasser & Almeida, 2017). The diversity and vibrancy of these initiatives stimulate a process of mutual inspiration and learning. At the same time, these discussions suffer from the absence of a sustained, integrative layer of engagement. What is missing is a sustained international dialogue that weaves threads of discussions in these many groups into a meta-narrative that addresses the broader human rights, ethical, legal, economic, and social aspects of AI, which will be clarified if AI is truly to serve the human good. We believe that this is a new role for a process that we call “new technology diplomacy.”

Unlike in other emerging technological fields, such as 5G, there is currently little exploration of the possible modes for AI international collaboration. This is an unfortunate deficit at this critical juncture when there are no industry-backed, global, standardisation bodies; when the existing, conventional ICT governance methods are too slow to adapt dynamically to the ever changing technical developments; and when most of the impact of AI will be universal. In view of the increasingly confrontational situation described in previous sections., it is possible to conduct a scoping exercise to signal a realistic orientation of such a system and some of its main constituents, even though it is too early to propose an exhaustive collaboration mechanism.

The contributors to this article note the principal advantages and flexibility of polycentric models of international, collaborative governance. In a multi-stakeholder, multi-layer model, such a mechanism would be able to accommodate inter-governmental discussions and other existing or new initiatives from industry fora to existing, international institutions and civil society. The internet has been governed using a variant of collaborative, multi-stakeholder governance and overall, this model has worked well, even though it has also revealed many challenges that would have to be overcome in AI (e.g., Mueller, 2010; DeNardis, 2014, 2020). In principle, international collaborative governance offers several benefits (Ansell & Gash, 2007). First, it helps avoid the high costs of adversarial policy making and promotes the development of more productive relationships among stakeholders. Specifically, it offers geopolitical adversaries a legitimate platform to engage in productive discussions. Second, it fosters synergy among nations and firms in the development of AI, especially in standards setting, knowledge diffusion, and applications. Third, international collaborative governance can monitor and address the risks of harmful, AI-based applications. This allows the global society to benefit from AI while minimizing its potential threats, including the risk of a cataclysmic event which, according to a warning by Stephen Hawking, can only avoided if AI is “strictly and ethically controlled.“25

We term this overarching approach “new technology diplomacy,” - a renewed kind of international engagement aimed at transcending narrow national interests and seeks to shape a global set of principles. This process would complement existing decentralised discussions and would ideally serve as an integrating fabric. It would be sufficiently flexible to allow for competition between differentiated policy approaches while also offering opportunities for mutual inspiration, comparative learning, and harmonisation. Ideally, such a larger vision beyond that of conventional diplomacy would allow the provision of guidance, reconcile bottom-up and top-down initiatives from interested parties, and, eventually, lead to an international constitutional charter for AI.

New technology diplomacy would allow addressing both the generic aspects of AI and the sector-specific applications. Because much of AI and IT are dual and multi-use technologies, it would also allow engaging in civil and security concerns. In the joint efforts to build international, collaborative governance, pioneering stakeholders may start with informal and humble initiatives to build momentum. These diplomacy efforts, however, should place a special focus on strengthening the determinants of effectiveness, including the willingness to collaborate with a shared understanding of what collective efforts can achieve: trust, communication, mutual respect, and leadership (Scott & Thomas, 2017).

Many experts agree that cooperation between countries is the most powerful means to avoid the negative repercussions of techno-nationalism, protectionism, and fragmentation (Lee, 2019). Technology and innovation have already become key topics in international relationships, particularly in relation to AI. Policy and regulation26 are the key constituents of future decisions about AI. 27 In the following, a brief discussion of some of the existing and/or more immediate forms of cooperation are presented. The objective is to illustrate the feasibility of an international, collaborative governance and the potential for a new technology diplomacy.

Within this new framework for technology diplomacy, there are basically two generic modes of direct cooperation through technology: one from research and the other from institutions with global interests. Research today is already global. Yet, there are still a number of fundamental challenges28 in AI where collaboration would allow for strengthened results that would bring global benefits (Leijten, 2019). But large firms in AI are also international and aim to grow to become truly global in their geographical reach. They could become dominant in the markets supported by the countries and regions to which they belong 29 in a privatised and competitive model of global innovation. In both cases, the prevention of malicious usages of AI is part of the cooperation. There are important commonalities across jurisdictions in this domain where joint prevention and mitigation strategies can be found. In fact, several practical, related avenues for cooperation already exist and could be adapted to AI. They include participation with and learning from the cybersecurity community, standardisation of best practices, red teaming, formal verification, and the responsible disclosure of vulnerabilities. Also included are the development of security tools and secure hardware, the pre-publication of risk assessment in technical areas of special concern, sharing regimes that favour safety and security, and the promotion of a culture of responsibility through education, ethical statements, standards, framings, norms, and expectations (Brundage et al., 2018). Collective understanding and dialogue will benefit all interested parties, but coordination is the most difficult challenge.30

One high-level question is whether existing institutions can be modified to address AI global challenges with a local/regional impact. It seems relevant here to strengthen domestic R&D in collaboration with academic and R&D institutions from across the world. But diplomatic processes that strengthen such exchanges of knowledge would need to evolve. Several countries have such existing mechanisms for emerging technologies. Would AI be just another stream? Because AI algorithms typically deal with large amounts of data, how should such collaborations be crafted when taking into consideration national sensitivities and regulation around data privacy and localisation? For the latter, national foreign policy and a collective approach across diplomatic regimes should address whether new mechanisms are required. Would existing multi-lateral mechanisms, such as the Budapest Convention, be sufficient? If yes, would the scope and charter need to be modified in the context of AI?

Essential elements in such a new technology diplomacy initiative would include having a sufficient number of countries on board to achieve a critical mass. We envision that this process could evolve organically and parallel more decentralised initiatives. In many jurisdictions, this would require reshaping domestic foreign policy-related institutions and strengthening human resource capabilities and processes so that these are in coherence with emerging implications of AI for national sovereignty. AI's implications for foreign policy require a comprehensive approach that links national and international institutions; it cannot be addressed adequately merely by having an AI expert in the foreign policy process. Thus, as mentioned, an effective approach should include not only foreign policy civil servants but multiple stakeholders from the private sector, academia, and various relevant branches of the government. In many instances, the adoption of such an approach would require significant reform at the national level, because most foreign-related ministries, especially in developing countries, work in a siloed manner.

New technology diplomacy in AI will require going beyond formal, multi-lateral institutions and instruments such as treaties. There are several sectoral organisations outside the UN system that work effectively with member countries to achieve their objectives. An example is the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), 31 an intergovernmental policy-making body that has levels of membership for countries based on their acceptance of processes mandated by it to achieve its objectives of “preventing illegal financial activities and the harm they cause to society.” It does so by generating the necessary political will to bring about national legislative and regulatory reforms in these areas. Similar structures and institutions may need to be designed to advance the tasks and objectives of technology diplomacy. Because the scope of AI cuts across various domains, the proposed design of intergovernmental policy-making bodies should include at least technology experts and private sector and human rights organisations.

New technology diplomacy could unfold initially as a series of meetings, possibly even a global conference on AI. Lessons could be drawn from previous experiences, such as the two World Summits on the Information Society (WSIS) convened under United Nations auspices; the establishment of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) or the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The latter was convened during a time of great international tension and conflict. However, the traditional inter-governmental model falls short of the envisioned open process that involves multiple stakeholders and hence needs to be augmented with complementary modes. It would be possible to establish “corporate diplomats” (recognizing the de facto influence of large technology corporations) and “citizen diplomats” in addition to known government diplomats. Although existing organisations, such as the G20, the OECD, or UN organisations could take on some of the tasks, we believe that a dedicated organisation would better be able to address the challenges.

An additional interesting component of such cooperation would be its openness. Openness would help, for instance, to achieve accountability and transparency in the algorithms within AI and would avoid the full privatisation of research outcomes. Complementary data ethics32 and governance schemes would need to be developed, especially if data needed to be shared across participants located in different jurisdictions. Ethical challenges for data governance include consent, ownership, privacy, delegation, and responsibility (Taddeo & Floridi, 2018). More precisely, data exchanges would be needed to tackle global challenges more effectively in areas where AI can play a key role, for example, in healthcare,33 quality of life, or sustainability and climate change.

The task of AI-based technology diplomacy would need experts that are not only well versed in the conventional, foreign policy domain but also in the technology domain and its implications for business, society, and nations. Such personnel may not be readily available through a traditional process of civil servant selection. Their tasks would include, among others: (i) formulating relevant national policies and the position of the government in areas where AI intersects with international relations within the domestic security and ethical framework; (ii) creating the environment for such AI-contextualised policies to be accepted through appropriate communication and discussions at various levels with the involvement of a variety of actors, such as civil society, academia, and media; (iii) working with bilateral and multilateral agencies, reviewing different agendas, and coming up with acceptable norms for behaviour and review processes for AI-based transnational systems; and (iv) coordinating the implementation of such norms through formal mechanisms such as agreements, treaties, and informal mechanisms, such as confidence-building measures,34 research studies, grants, etc.

8. Conclusion

AI promises tremendous benefits for humanity that will affect nearly all areas of work and daily life. AI is being widely diffused, and its power is rapidly increasing and being supported by enabling technological and social conditions. Many promising applications are emerging across many industries. At the same time, AI also offers many opportunities for abuse. Recognizing this hybrid nature, many initiatives among civil sector organisations, non-profits, businesses, non-government and government organisations are under way to address the pressing technical, economic, ethical, and societal issues. These discussions unfold currently in an environment of decreased trust in global collaboration. Tech-nationalism, protectionism, and dysfunctional fragmentation might undermine the benefits AI can bring while increasing the risk of abuse by state and non-state players. We believe that a new technology diplomacy, envisioned as a multi-stakeholder, multi-layer, bottom-up and top-down process is needed to weave the many existing initiatives into a broader narrative. A critical mass of visionary leaders in government, corporations, non-profit organisations, research institutions, and initiatives on the ground can make a difference. This will not be an easy nor a straightforward process, but it is necessary to realise the full benefits of AI for the largest number possible.

Footnotes

The case of car manufacturing is relevant. As of Ma, 2018, with a view to stimulating the development of electric cars, China has lifted the limitations on foreign participation in this industry.

Some partial exceptions are perhaps the area of smart cities, where companies such as Cisco or Siemens have participated in developments, and the area of cloud computing, where Amazon, Microsoft, and IBM are present in alliances with Chinese companies whose market shares are small and future prospects weak.

Chinese investments in Europe have grown from €16 billion in 2010 to €35 billion in 2016. In a historic shift, the flow of Chinese direct investment into Europe has surpassed the declining flows of annual European direct investments into China (Seaman, Huotari, & Otero-Iglesias, 2017).

Chinese vendors have traditionally benefitted from cheaper equipment and services prices and lately from Snowden's revelations about the US interference with communications. However, there is still distrust of Chinese providers in the EU with respect to national security. Equipment manufactured by ZTE Corporation can not to be used in the United Kingdom, for instance, whereas that of Huawei can be subject to certain limitations. In contrast, both of these companies have been practically vetoed in the United States. On the other side, US providers are also subject to restrictions in China, because of similar cybersecurity concerns and the Chinese leader's vindictive streak.

Taxes on equipment are a separate issue from taxes on the revenue from application platforms. The latter relate to matters of physical security, whereas the former relate to economic security and/or viability. However, both lead to the same end: an increase in protectionism and policy fragmentation.

The proposed list of products subject to added import tariffs from China to the United States is more or less the same as the industries listed within the Made in China 2025 plan.

The title of this section and some of its key ideas are taken from Bremmer and Kupchan (2018).

Social networks and search engines are the paramount example. There is no Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or WhatsApp in China; instead they have Baidu, Weibo, and WeChat, to name just the most well-known. This is also happening in other countries with increasing restrictions, such as in Russia, Vietnam, and others.

It is not only China and Russia that are contemplating separate Internet spheres. As already mentioned, the United States is placing increasing limitations on hardware and software coming from China. Looking from the outside, the EU is perceived as a data-privacy-obsessed bloc of countries. There are also interesting precedents of the Chinese market being opened up to foreign providers when most of it has already been captured by domestic companies or the appeal of the solutions has passed. See, for instance, the case of Sony's PlayStation.

On the other hand, the potential for technology to differentiate one company from the others —its strategic potential— inexorably declines as the technology becomes accessible and affordable to all, although innovators and early adopters have notable advantages.

https://www.edge.org/conversation/kai_fu_lee-we-are-here-to-create (Accessed 3 May 2020).

However, the massive implementation of technologies such as IoT could multiply data in any country.

A major concern in the EU, for instance (Stix, 2018).

Elon Musk famously tweeted, “Competition for AI superiority at national level most likely cause of World War 3 in my opinion.” See https://www.wired.com/story/emmanuel-macron-talks-to-wired-about-frances-ai-strategy/(Accessed 3 May 2020).

https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/futuro-del-trabajo/(Accessed 3 May 2020). The United States has already announced that it will start considering placing limitations on Chinese scientists working on key projects at companies and universities in the United States.

Most, but not all, experts deemed this possibility too futuristic.

H.R.4625 - Fundamentally Understanding The Usability and Realistic Evolution of Artificial Intelligence Act of 2017 or FUTURE of Artificial Intelligence Act of 2017. Because it was not passed during that Congress, it is unlikely that it will move forward.

This is the case of companies such as Microsoft and Alphabet (Google), that also argue for the clash between transparency and accountability and their IP rights, trade secrets, and security (World Economic Forum, 2018a).

https://techcrunch.com/2018/03/14/a-hippocratic-oath-for-artificial-intelligence-practitioners/(Accessed 3 May 2020).

https://www.wired.com/story/emmanuel-macron-talks-to-wired-about-frances-ai-strategy/(Accessed 3 May 2020).

Deep learning can be problematic in terms of transparency. According to Pedro Domingos, “The best learning algorithms are these neural network-based ones inspired by what we find in humans and animals. These algorithms are very accurate as they can understand the world based on a lot of data at a much more complex level than we can. But they are completely opaque. Even we, the experts, don't understand exactly how they work. We only know that they do. So, we should not allow only algorithms which are fully explainable. It is hard to capture the whole complexity of reality and keep things at the same time accurate and simple.” See http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/pedro-domingos-on-the-arms-race-in-artificial-intelligence-a-1203132.html (Accessed 3 May 2020). For this reason, some experts argue for more fundamental research into how deep learning works.

There are also some other EU-specific difficulties because, in essence, the digital, single market is not in place. Referring to cybersecurity, they can be summarised as: (1) lack of funding for companies to scale up, (2) fragmentation of European industry, (3) strong dependence on non-EU providers, (4) misalignment between public R&D programs and market needs, (5) regulatory fragmentation, and (6) lack of common standardisation and procurement requirements across member states (Rivera et al., 2017).

In the words of French President Macron, “avoiding the opaque privatisation of AI or its potentially despotic usage.” See http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/03/emmanuel-macron-wants-france-become-leader-ai-and-avoid-dystopia (Accessed 3 May 2020).

“Six Dangerous Risks of Artificial Intelligence”, by Mike Thom, April 7, 2020, Built In, available at https://builtin.com/artificial-intelligence/risks-of-artificial-intelligence. This article also quotes Elon Mask as saying that “AI is far more dangerous than nukes.”

Regulation has, strictly speaking, failed to tackle the subset of issues related to privacy within new technologies such as AI or big data (Gómez-Barroso, Feijóo, & Martínez, 2017). The EU is also perceived abroad as leaning on privacy and antitrust regulation just because of its industry shortcomings. See https://www.edge.org/conversation/kai_fu_lee-we-are-here-to-create (Accessed 3 May 2020).

According to Bruce Schneier, legislation itself will not be enough, because, as the Snowden case has proved, although technology can subvert law, law can also subvert technology. See http://nymag.com/selectall/2017/01/the-internet-of-things-dangerous-future-bruce-schneier.html (Accessed 3 May 2020).

Experts highlight that the current developments in AI are based on relatively old algorithms. Advances in AI need breakthroughs in areas such as human, common-sense knowledge, extraction of semantics, use of small data to solve problems, knowledge graphs, machine learning for both knowledge and behaviour, machine teaching, and algorithm explainability.

In the words of France's President Macron, “When you look at artificial intelligence today, the two leaders are the US and China. In the US, it is entirely driven by the private sector, large corporations, and some startups dealing with them. All the choices they will make are private choices that deal with collective values […] On the other side, Chinese players collect a lot of data driven by a government whose principles and values are not ours. And Europe has not exactly the same collective preferences as US or China. If we want to defend our way to deal with privacy, our collective preference for individual freedom versus technological progress, integrity of human beings and human DNA, if you want to manage your own choice of society, your choice of civilisation, you have to be able to be an acting part of this AI revolution”. See https://www.wired.com/story/emmanuel-macron-talks-to-wired-about-frances-ai-strategy/(Accessed 3 May 2020).

It has been claimed that this is not the first time humanity has risen to meet such a challenge: “The NATO conference at Garmisch in 1968 created consensus around the growing risks from software systems, and sketched out technical and procedural solutions to address over-run, over-budget, hard-to-maintain and bug-ridden critical infrastructure software, resulting in many practices which are now mainstream in software engineering; the NIH conference at Asilomar in 1975 highlighted the emerging risks from recombinant DNA research, promoted a moratorium on certain types of experiments, and initiated research into novel streams of biological containment, alongside a regulatory framework such research could feed into” (Brundage et al., 2018).

See an interesting proposal at Loukides, Mason, and Patil (2018).

The case of the developments around the control of the 2019 coronavirus epidemy is paradigmatic.

New mechanisms for trust and confidence-building measures might be needed not only between China and the United States—the top competitors in comprehensive national strength today—but also among a larger group of AI players, including Canada, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Russia, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

Contributor Information

Claudio Feijóo, Email: claudio.feijoo@upm.es.

Youngsun Kwon, Email: yokwon@kaist.ac.kr.

Johannes M. Bauer, Email: bauerj@msu.edu.

Erik Bohlin, Email: erik.bohlin@chalmers.se.

Bronwyn Howell, Email: bronwyn.howell@vuw.ac.nz.

Rekha Jain, Email: rekha@iima.ac.in.

Petrus Potgieter, Email: php@grensnut.com.

Khuong Vu, Email: vuminhkhuong@nus.edu.sg.

Jason Whalley, Email: jason.whalley@northumbria.ac.uk.

Jun Xia, Email: xiajun@bupt.edu.cn.

References

- A web of silk . 2018. The economist.https://www.economist.com/china/2018/05/31/china-talks-of-building-a-digital-silk-road Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell C., Gash A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2007;18(4):543–571. [Google Scholar]

- Baccala M., Curran C., Garett D., Likens S., Rao A., Ruggles A. 2018. AI predictions: 8 insights to shape business strategy.https://www.pwc.com/us/en/advisory-services/assets/ai-predictions-2018-report.pdf PwC. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BeijingAcademy of Artificial Intelligence . 2019. Beijing AI principles. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Beishon M. Is it time to regulate artificial intelligence? InterMedia. 2018;45(4):20–24. http://www.iicom.org/images/iic/intermedia/Jan-2018/im-jan018-artificial-intelligence.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer I.A.N., Kupchan C. 2018. Top risks 2018.https://www.eurasiagroup.net/files/upload/Top_Risks_2018_Report.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Brundage M., Avin S., Clark J., Toner H., Eckersley P., Garfinkel B. Future of Humanity Institute; 2018. The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation authors are listed in order of contribution design direction.https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/3d82daa4-97fe-4096-9c6b-376b92c619de/downloads/1c6q2kc4v_50335.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher J., Beridze I. What is the state of artificial intelligence governance globally? The RUSI Journal. 2019;164(5–6):88–96. [Google Scholar]

- CBInsights . CBInsights; 2018. Top AI trends to watch in 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry N., Mejias U.A. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2019. The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. [Google Scholar]

- Craglia M., Annoni A., Benczur P., Bertoldi P., Delipetrev P., De Prato G.…Tuomi I. Publications Office; Luxembourg: 2018. Artificial intelligence - a European perspective. EUR 29425 EN. doi:10.2760/11251, JRC113826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardis L. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2014. The global war for internet governance. [Google Scholar]

- DeNardis L. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2020. The internet in everything: Freedom and security in a world with no off switch. [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom J. Rand Corporation; 2018. Systems confrontation and system destruction warfare. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision . 2016. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj Available at: [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2017. Report from the commission to the European parliament and the council on trade and investment barriers. Brussels. [DOI] [Google Scholar]