Abstract

Craniopharyngioma is an uncommon intracranial tumor that primarily occurs in the sella turcica. Giant cystic craniopharyngioma is rare in general and extremely rare in adults. We report a rare case of giant cystic craniopharyngioma in the anterior pontine cisterna and suprasellar cisterna. A 27-year-old man presented with double vision, and craniocerebral MRI revealed cystic masses in the anterior pontine cisterna and suprasellar cisterna. The masses were removed surgically and diagnosed as large cystic craniopharyngiomas by pathology and MRI. Giant cystic craniopharyngioma is rare in adults. Through this case report, we hope to increase awareness of this disease among various clinicians, including radiologists.

Keywords: Craniopharyngioma, Giant cells, Giant cystic craniopharyngioma

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; WHO, World Health Organization; CNS, central nervous system; GPFCCPs, giant posterior fossa cystic craniopharyngiomas; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ACP, adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma; PCP, papillary craniopharyngioma

Introduction

Craniopharyngioma is a rare intracranial tumor that mainly originates from residual epithelial cells in Roethke's pouch and is mostly found in the sella turcica [1]. Giant posterior fossa cystic craniopharyngiomas (GPFCCPs) are rare and more common in children than adults [2], [3], [4]. Clinical symptoms of GPFCCPs mainly include increased intracranial pressure, headache, vomiting, and visual impairment [5]. Here, we report the case of a 27-year-old man with a brain tumor and visual impairment.

Case report

A 27-year-old male came to the hospital complaining of “double vision for 1 month with aggravated symptoms for half a month.” Craniocerebral MRI at our hospital showed cystic masses in the anterior pontine and superior sella turcica cisterns; these masses were approximately 52 mm × 26 mm × 61 mm, with an irregular shape and a clear edge (Fig. 1). The T1-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging signals were low, and the T2-weighted imaging signal was high; no significant enhancement was observed in the enhanced scan, and the vertebra basilar artery and branch arterioles were visible in the interior.

Fig. 1.

(a) Low sagittal T1WI signal (white arrow); (b) High coronal plane T2 flair signal (thick white arrow); (c) No enhancement in the cross-section T1 enhancement (black arrow); (d) Low DWI signal (thick black arrow). DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; T1WI, T1-weighted imaging.

Intraoperatively, the tumor was localized to the slope of the anterior pontine cistern, with the top of the mass at the bottom of the third ventricle, the bottom at the anterior margin of the foramen magnus, and the sides at the level of the inner auditory canal. After the tumor capsule was cut, yellow fluid containing cholesterol crystals flowed out.

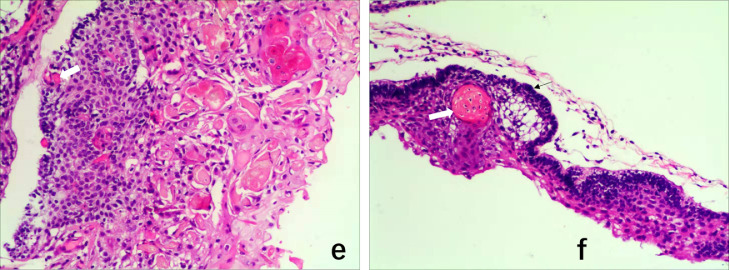

Postoperative pathology was performed (Fig. 2). The tumor was cystic, covering a thin layer of epithelium. Some sections were solid and lobulated, with palisade, polyhedral epithelial basal cells in the middle; some of these cells were arranged in a circular fashion. “Wet” keratin nodules, focal calcification, hyperemia, and edema mesenchyme were also observed, along with considerable lymphocyte infiltration. The initial diagnosis based on occupation of the right brainstem was adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP), and the addition of right brainstem imaging data led to a diagnosis of giant cystic ACP.

Fig. 2.

Tumor pseudopodia extend deep into the surrounding brain tissue and show wet keratin nodules (white arrows in panels e and f). The basal cells of the tumor epithelium are palisaded (f).

Discussion

Craniopharyngioma is a rare intracranial epithelial tumor with an estimated incidence of 0.13 cases per 100,000 per year. The age distribution is bimodal, peaking in childhood (5-14 years) and late middle age (50-74 years) [5,6]. Craniopharyngioma grows along the midline, mainly in the sella turcica, with some involvement of the suprasellar region; it can also present simultaneously in both the sellar and suprasellar regions [7]. Occasional cases have been reported in the nasopharynx, third ventricle, and lateral ventricle [8,9]. In this case report, we describe a young male with a lesion in the anterior bridge pool. Both the age at diagnosis and the tumor location are rare.

Craniopharyngioma is divided into 2 types, ACP and papillary craniopharyngioma (PCP); ACP is more common in children, and PCP is exclusive to adults [10]. This case of ACP pathology in a young male is extremely rare.

MRI scans are complicated to perform, and the results are varied due to the heterogenous histopathological manifestations of ACP. The typical imaging features of ACP are a high T1 signal, while CT shows calcification. In adults, 70.6% of ACP cases show calcification, and 58.8% have a high T1 signal. Craniopharyngioma with high T1 signal intensity can be secondary to high protein or cholesterol levels, mild calcification or bleeding [11,12]. In this case, MRI revealed a low T1 signal and a high T2 signal. Combined with histopathology, the data indicated a small number of cystic lesions that did not have a high protein or cholesterol concentration; rather, there was only a small amount of protein, so the mass manifested as long T1 and T2 signals.

Craniopharyngiomas are histologically benign (WHO grade I) but considered clinically aggressive due to their tendency to recur [9]. Because most craniopharyngiomas exhibit benign biological behavior, surgery is preferred [13]. According to the location, tumor size, and tumor growth direction, the clinicians can select from several surgical options, including endoscopic transsphenoidal dilatation or endoscopic endonasal approach for pediatric patients or craniotomy [14].

For patients who are candidates for surgery, total resection or subtotal resection plus radiotherapy are usually performed [15]. For craniopharyngioma patients with challenging recurrence or resection, treatment with adjuvant therapy, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy; or palliative therapy, such as vesicular aspiration, is an option [16]. Radiotherapy includes external radiotherapy, such as highly focused methods of intensity-modulated photon and proton therapy, and internal radiotherapy (90Y and 32P) [17,18]. For recurrent cystic craniopharyngioma, chemicals can be injected into the lumen to reduce cystic fluid secretion and control tumor growth [19]; the commonly used drugs are bleomycin and interferon D. It has been reported that tumors with aggressive characteristics have a higher recurrence rate and increased morbidity and mortality. Metabolic syndrome and hypothalamic obesity are the leading causes of death among patients with cystic craniopharyngioma. Hormone replacement therapies, including amphetamine derivatives and oxytocin supplementation, are potential therapeutic options for these patients.

Recently, scholars have detected BRAF V600E mutations in 95% of PCP patients and CTNNB1 mutations in 75%-96% of ACP patients [20]. Treatment with inhibitors targeting BRAF V600E was recently reported to be associated with the shrinkage of recurrent craniopharyngioma. Preoperative treatment with mutant BRAF inhibitors can reduce tumor size and thus facilitate subsequent surgery or radiotherapy. The BRAF V600E mutation can be predicted by the characteristics of craniopharyngioma in MR images. The BRAF V600E mutation was not considered in this case due to the imagining features [21].

The average size of craniopharyngiomas in adults is 3 cm, and GPFCCPs >6 cm in diameter or >60 ml in volume are rare and mostly occur in children [17]. Large craniopharyngiomas have been reported to extend forward to the sphenoid sinus and nasopharynx, rarely along the slope and backward to the cerebellopontine angle. Giant craniopharyngioma in adults has been reported only a few times, but giant ACP in adults has not been reported previously. In this case, the lesion was approximately 52 × 26 × 61 mm, indicating an extremely rare adult giant ACP.

Conclusion

Giant cystic ACP is rare in adults. The age, imaging manifestations, lesion location, and lesion size in this patient were all rare. It is hoped that this case report will provide more knowledge to clinicians, including radiologists, to improve the accuracy of diagnosing this rare disease.

Contributor Information

Si-ping Luo, Email: 867418862@qq.com.

Han-wen Zhang, Email: zhwstarcraft@outlook.com.

Juan Yu, Email: yujuan0072@qq.com.

Juan Jiao, Email: jiaojuan1225@sina.cn.

Ji-hu Yang, Email: yangjh810@163.com.

Yi Lei, Email: 13602658583@163.com.

Fan Lin, Email: foxetfoxet@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Muller HL, Merchant TE, Warmuth-Metz M, Martinez-Barbera JP, Puget S. Craniopharyngioma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):75. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young S, Zimmerman R, Nowell M, Bilaniuk L, Hackney D, Grossman R, et al. Giant cystic craniopharyngiomas. 1987;29(5): 468–473. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Buhl R, Lang E, Barth H, Mehdorn HM. Giant cystic craniopharyngiomas with extension into the posterior fossa. Adult CNS Radiation Oncology. 2000;16(3):138–142. doi: 10.1007/s003810050480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sener R, Kismali E, Akyar S, Selcuki M, Yalman O. Large craniopharyngioma extending to the posterior cranial fossa. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1997;15(9):1111–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karavitaki N, Cudlip S, Adams CB, Wass JA, Craniopharyngiomas. Endocrine Reviews 2006;27(4): 371–397. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Diniz LV, Jorge Junior LA, Rodrigues LP, Vieira Veloso JdC, Yamashita S. Intraventricular craniopharyngioma: a case report. J Neurol Stroke. 2018;8(3) doi: 10.15406/jnsk.2018.08.00306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahdi MA, Krauss JK, Nakamura M, Brandis A, Hong B. Early ectopic recurrence of craniopharyngioma in the cerebellopontine angle. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28(2):313–316. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.17215-16.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwasaki K, Kondo A, Takahashi JB, Yamanobe K. Intraventricular craniopharyngioma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surgical Neurology 1992;38(4): 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Palmer JD, Song A, Shi W. Craniopharyngioma. Adult CNS Radiat Oncol. 2018;3:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee IH, Zan E, Bell WR, Burger PC, Sung H, Yousem DM. Craniopharyngiomas: radiological differentiation of two types. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59(5):55–65. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Anna G, Grimaldi M, Scotti G. Neuroradiological diagnosis of craniopharyngiomas. Diagn Manage Craniopharyng. 2016;3:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prieto R, Pascual JM, Barrios L. Topographic diagnosis of craniopharyngiomas: the accuracy of MRI findings observed on conventional T1 and T2 images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(11):2073–2080. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emanuelli E, Frasson G, Cazzador D, Borsetto D, Denaro L. Endoscopic transsphenoidal salvage surgery for symptomatic residual cystic craniopharyngioma after radiotherapy. J Neurol Surg Part B: Skull Base. 2018;79(S 03):S256–S258. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageji T, Miyamoto T, Kotani Y, Kaji T, Bando Y, Mizobuchi Y. Congenital craniopharyngioma treated by radical surgery: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33(2):357–362. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rock AK, Dincer A, Carr MT, Opalak CF, Workman KG, Broaddus WC. Outcomes after craniotomy for resection of craniopharyngiomas in adults: analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) J Neurooncol. 2019;144(1):117–125. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grob S, Mirsky DM, Donson AM. Targeting IL-6 is a potential treatment for primary cystic craniopharyngioma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:791. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graffeo CS, Perry A, Link MJ, Daniels DJ. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: a primer for the skull base surgeon. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018;79(1):65–80. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1621738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liubinas SV, Munshey AS, Kaye AH. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(4):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller HL, Merchant TE, Puget S, Martinez-Barbera J-P. New outlook on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(5):299–312. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Tong Y, Shi Z, Chen H, Yang Z, Wang Y. Noninvasive molecular diagnosis of craniopharyngioma with MRI-based radiomics approach. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12883-018-1216-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue Q, Yu Y, Shi Z, Wang Y, Zhu W, Du Z. Prediction of BRAF mutation status of craniopharyngioma using magnetic resonance imaging features. J Neurosurg. 2018;129(1):27–34. doi: 10.3171/2017.4.JNS163113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]