Abstract

Large dense-core vesicles (LDCVs) contain a variety of neurotransmitters, proteins, and hormones such as biogenic amines and peptides, together with microRNAs (miRNAs). Isolation of LDCVs is essential for functional studies including vesicle fusion, vesicle acidification, monoamine transport, and the miRNAs stored in LDCVs. Although several methods were reported for purifying LDCVs, the final fractions are significantly contaminated by other organelles, compromising biochemical characterization. Here we isolated LDCVs (chromaffin granules) with high yield and purity from bovine adrenal medulla. The fractionation protocol combines differential and continuous sucrose gradient centrifugation, allowing for reducing major contaminants such as mitochondria. Purified LDCVs show robust acidification by the endogenous V-ATPase and undergo SNARE-mediated fusion with artificial membranes. Interestingly, LDCVs contain specific miRNAs such as miR-375 and miR-375 is stabilized by protein complex against RNase A. This protocol can be useful in research on the biological functions of LDCVs.

Subject terms: Synaptic vesicle exocytosis, Molecular neuroscience, Neurotransmitters

Introduction

Neurons communicate by neurotransmission, which involves vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release1,2. Synaptic vesicles and large dense-core vesicles (LDCVs) participate in different functions in the nervous system3,4. Synaptic vesicles in the presynapse store classical neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, acetylcholine, GABA, and glycine), and mainly activate ion channels in the postsynaptic terminals, thereby transmitting electrical signals to the postsynapse. In contrast, LDCVs contain amines, neuropeptides, and other hormones that mainly stimulate G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate synaptic responses3–5. LDCVs are minor components, amounting to only 1~2% when compared to synaptic vesicles in the central nervous system6–8, but they are highly abundant in specialized brain regions (such as the hypothalamus), in dopaminergic neurons and in sympathetic neurons of the peripheral nervous system6.

Chromaffin cells are modified sympathetic ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system7,8. Chromaffin cells are enriched with LDCVs, also called chromaffin granules, and therefore constitute a widely-used model system for in-depth study of LDCVs9. LDCVs of chromaffin cells contain catecholamines (i.e., adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine), peptides (e.g., encephalin and neuropeptide Y), and proteins (chromogranins, secretogranins)10. Recently, we reported that LDCVs store microRNAs (miRNAs), which are released by vesicle fusion in response to stimulation, and miR-375 is the most abundant miRNA in LDCVs11,12.

A protocol to isolate LDCV from bovine adrenal medulla was reported in the 1950s13, then modified14 to include step density gradient centrifugation in the late 1960s. This protocol was widely used in many studies and formed the basis for establishing the proteomics of LDCVs15, and for identifying their content including amines, peptides, and proteins released by LDCV exocytosis10. However, the purity of LDCVs isolated by this protocol is limited, compromising biochemical and biophysical studies of isolated LDCV.

Here, we present a modified protocol for obtaining LDCVs with high yield and high purity from bovine adrenal medulla. The conventional methods for LDCV isolation use a sucrose step gradient of high density16,17. Upon centrifugation LDCVs migrate through these high density sucrose solutions (e.g., 1.6 M) whereas other organelles exhibiting lower buoyant density largely remain on top of the sucrose layer. However, the buoyant density of mitochondria overlaps slightly with that of LDCVs, so contamination with mitochondria is a serious problem. The protocol for LDCV isolation described here improves the purity by i) increasing the maximal sucrose concentration to 2.0 M and ii) applying a continuous sucrose density gradient.

The protocol outlined and illustrated (Figs. 1 and 2) for LDCV isolation yields highly pure LDCVs, mostly excluding mitochondria (Fig. 3). Purified LDCVs retain activity in V-ATPase-dependent acidification as well as in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion (Fig. 4). miR-375, the most abundant miRNA stored in LDCVs, remains stable even in the presence of RNase A. We provide evidence showing that miR-375 can be stabilized by protein complex against the degradation by RNase A (Fig. 5). This protocol will be useful in research on the biological functions of LDCVs, including vesicle fusion, vesicle acidification, monoamine transport, and the functions of miRNAs stored in LDCVs.

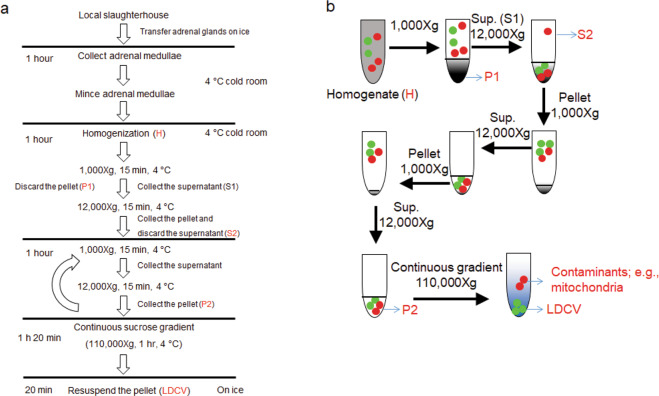

Figure 1.

Schematic overview over the procedure for isolating LDCVs from bovine adrenal medulla. (a) Overview of timing and purification protocol to isolate LDCVs. (b) Schematic of LDCV isolation. Green: LDCVs; Red: contaminant organelles (e.g., mitochondria). Black, gray: cell debris.

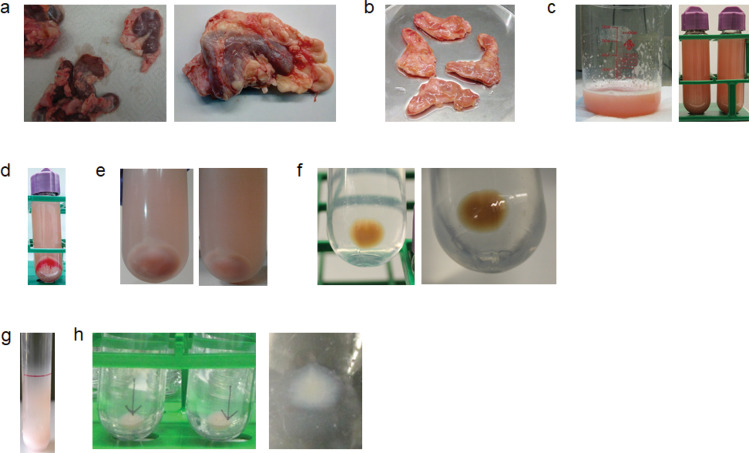

Figure 2.

Photos of individual steps during the purification of LDCVs. (a) Adrenal glands transported on ice from local slaughterhouse. Note that adrenal glands are surrounded by fat. (b) Adrenal medullae after removal of adrenal cortex. (c) Homogenate (H) of adrenal medullae after homogenization. (d) Supernatant (S1) and pellet (P1) after centrifugation. (e) P2 fraction before and, (f) after washing. (g) LDCV distribution after continuous sucrose gradient. LDCVs are pink, which results from the presence of cytochrome b561 in the LDCV membrane27, whereas mitochondria are brown. Note that the pellet is pink and the supernatant is brown. (h) After removing the supernatant, pellet are LDCVs.

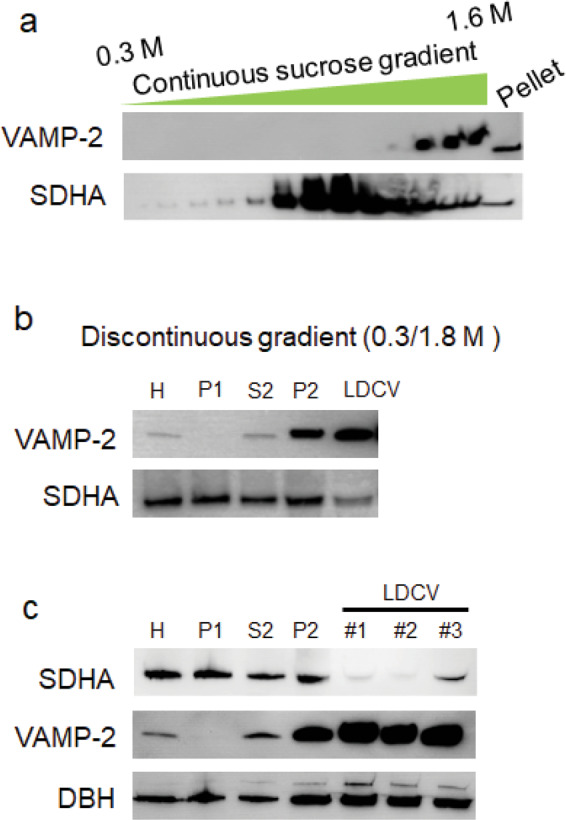

Figure 3.

Separation of LDCVs from mitochondria by increasing the maximal density. (a) Continuous sucrose gradient from 0.3 M to 1.6 M was used, which resembles conventional protocols. Profile of VAMP-2 (a marker for LDCV membranes) and succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (SDHA, a marker for mitochondria) across gradient fractions. Aliquots of equal volume from each fraction were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, as described elsewhere18. Mitochondria (SDHA) contaminants were present throughout the gradient and are still significant in the pellet fraction containing the LDCVs. (b) The LDCV fraction was recovered from the pellet after a discontinuous sucrose gradient in which a 1.8 M sucrose cushion was overlaid with 0.3 M sucrose. 20 μg of proteins from each fraction were subjected to immunoblotting. Homogenate (H), the pellet containing nuclei and cell debris (P1), second supernatant (S2), crude LDCV (P2), large dense-core vesicle (LDCV). (c) Mitochondrial contamination of LDCV pellets varies with the type of sucrose gradient: #1: continuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/1.9 M), #2: continuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M), #3: discontinuous gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M). SDHA (marker for mitochondria). VAMP-2 and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (DBH) are markers for LDCVs. Full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Information.

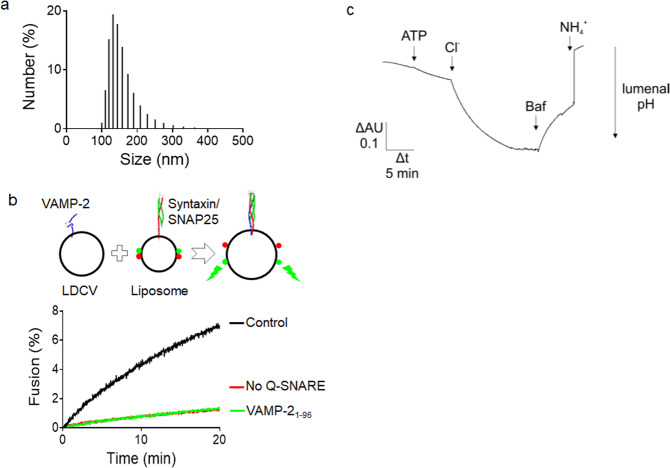

Figure 4.

Biophysical and biochemical properties of purified LDCVs. (a) Size distribution of purified LDCVs analyzed using dynamic light scattering. The histogram shows the numbers as percentage of total. Average diameter of LDCVs is 153.7 nm, with a standard deviation (SD) of 42.2 nm. (b) Fusion of LDCVs with liposomes containing SNARE acceptor complexes. Fusion was measured by dequenching of labeled membrane lipids (lipid mixing)18,22,28 (top). Plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes contain phospholipids labelled with NBD (green fluorescence) and rhodamine (red fluorescence). The stabilized Q-SNARE complex (syntaxin-1A and SNAP-25A) called the deltaN complex23 is reconstituted in liposomes that mimic the plasma membrane. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two fluorophore-labeled lipids is reduced after LDCV fusion due to lipid dilution by unlabeled lipids of LDCVs, thus de-quenching the donor fluorescence. Soluble synaptobrevin-2 (VAMP-21-96) and omission of SNAREs in liposomes prevented lipid mixing (bottom). Fluorescence values are normalized as a percentage value of the maximum donor fluorescence induced by 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (TX-100) detergent treatment at the end of experiments. (c) ATP and Cl- dependent acidification in LDCVs. LDCV acidification was monitored using 1 mM acridine orange as a reporter dye. The reaction was started by the addition of 1.2 mM MgATP followed by 50 mM KCl. Addition of 0.2 µM of the V-ATPase inhibitor Bafilomycin results in luminal re-alkalinization, indicating V-ATPase-specific proton pumping. The reaction was stopped by adding 15 mM (NH4)2SO4 which equilibrates the luminal pH with that of the medium.

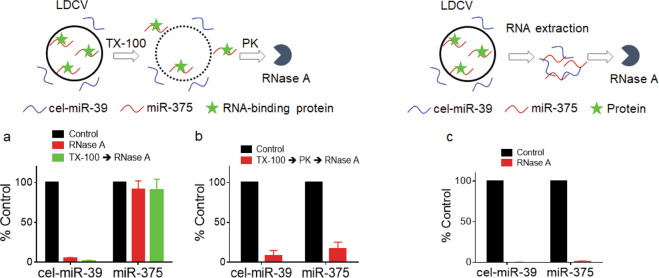

Figure 5.

Detection of miR-375 stored in LDCVs. (a) Schematic of test for miR-375 stored in LDCVs (top); 1% (vol/vol) TX-100 was incubated with LDCVs to disrupt the vesicle membrane. RNase A was then applied to degrade miR-375. Relative levels of miR-375 with or without 1% (vol/vol) TX-100 were determined by qRT-PCR (bottom). (b) LDCVs were treated with Proteinase K in the presence of TX-100, followed by RNase A treatment. (c) RNase A was applied after RNA extraction using the miRNeasy Mini Kit. Proteins are removed from RNA samples. Values represent a percentage of control and data are mean ± SD from three to four independent replicates.

Results

LDCV isolation

LDCVs were isolated from bovine adrenal medulla by combining differential and continuous sucrose gradient centrifugation; schematic overview and photos of individual steps during the purification are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2. The quality of purified LDCVs can be checked using immunoblotting18 (Fig. 3). We first tested the purity of LDCVs isolated using the conventional protocols. The conventional methods applied a sucrose step gradient of high density, which exploits the fact that LDCVs have the highest known buoyant density of all organelles16,17. Smith and Winkler used 0.3 M/1.6 M sucrose gradient to purify LDCVs14 and we observed that the continuous sucrose gradient from 0.3 M to 1.6 M gives rise to the serious contamination of mitochondria (Fig. 3a). VAMP-2 and succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (SDHA) as protein markers represent the presence of LDCV and mitochondria, respectively. LDCVs migrate into the pellet fraction due to their high buoyant density, whereas other organelles largely remain on top of the sucrose layer. We only collected the pellet fraction for LDCVs after continuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. However, the buoyant density of mitochondria overlaps slightly with that of LDCVs. Mitochondria contaminants (SDHA) are present throughout the gradient and are still significant in the pellet fraction containing LDCVs in the conventional method that use 0.3 M/1.6 M sucrose gradient (Fig. 3a).

We next tried discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation with 0.3 M/1.8 M sucrose to isolate LDCVs (Fig. 3b). Mitochondria (SDHA) is still present in the pellet together with LDCVs; LDCVs are from the pellet fraction, proposing that 0.3 M/1.8 M sucrose gradient method is limited for isolating LDCVs with high purity. Then we examined mitochondrial contamination from LDCV pellets using the different sucrose gradient (Fig. 3c): i.e., #1: continuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/1.9 M), #2: continuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M), #3: discontinuous gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M). SDHA is mostly removed, whereas VAMP-2 and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (DBH), markers for LDCVs, are highly enriched in the continuous sucrose gradient with 0.3 M/2.0 M compared to the discontinuous sucrose gradient (Fig. 3c), suggesting that continuous sucrose gradient is much better for the high purity than discontinuous sucrose gradient. Taken together, we improved the purity of LDCV by i) increasing the maximal sucrose concentration to 2.0 M and ii) applying a continuous sucrose density gradient. This protocol is optimized to improve the purity of LDCVs by removing mitochondrial contamination.

Dynamic light scattering analysis

Dynamic light scattering analysis was carried out to determine the size distribution of isolated LDCVs from bovine adrenal medulla, which give rise to 153.7 ± 42.2 nm (Fig. 4a). The diameter of purified LDCVs can also be measured using electron microscopy that showed a heterogeneous size distribution with an average diameter of 167.7 nm18, correlating with dynamic light scattering analysis (Fig. 4a). The average diameter of purified LDCVs with ~153 nm is smaller than that of total LDCVs in chromaffin cell; the average diameter is 356 nm19. It is because this method with 0.3 M/2.0 M continuous sucrose gradient purifies mainly mature LDCVs (smaller in size) whereas immature LDCVs are separated away18. Mature LDCVs become smaller and condensed through removal of water during the maturation process20,21, proposing that isolated LDCVs have high purity and mature LDCVs are mainly purified18.

Vesicle fusion assay using purified LDCVs

LDCVs frozen for several months are structurally and functionally intact as judged by functional assay. We measured the activity with respect to SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. The reconstitution of LDCV fusion was previously established using purified LDCVs18,22. Purified LDCVs fused with plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes that contain the stabilized soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (Q-SNARE) complex with high efficiency (Fig. 4b). Plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes containing NBD- and rhodamine-labeled phospholipids were reconstituted with the stabilized acceptor complex known as the ΔN complex: a preformed complex of syntaxin-1A (lacking the N-terminal Habc domain) and SNAP-25A containing the C-terminal fragment of VAMP-2 (residues 49–96)23. Liposomes contained 45% phosphatidylcholine, PC; 15% phosphatidylethanolamine, PE; 10% phosphatidylserine, PS; 25% cholesterol; 4% phosphatidylinositol, PI and 1% phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PI(4,5)P2. Fusion was monitored by a lipid-mixing assay in which fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two fluorophore-labeled lipids become reduced due to lipid dilution after vesicle fusion, thus causing de-quenching of the donor fluorophore24. LDCV fusion is SNARE-dependent18,22, because soluble VAMP-2 or lack of SNARE proteins in plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes completely block LDCV fusion (Fig. 4b).

Vesicle acidification by V-ATPase

Another functional assay for intact LDCVs is to test the activity with respect to luminal acidification. A key role of LDCVs is the accumulation of monoamines such as adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin prior to their release through SNARE dependent exocytosis. Monoamine loading into LDCVs relies on a proton electrochemical gradient (ΔμH+) generated by the V-ATPase in the LDCV membrane. In presence of ATP the V-ATPase pumps protons into the vesicle lumen which results in the formation of a proton gradient (ΔpH) and an inside positive membrane potential (ΔΨ). In absence of negative counter ions ΔpH is comparably small, as the V-ATPase is slowed down by the accumulation of positive charges in the vesicle lumen. However, in presence of membrane permeable anions such as Cl−, anion co-influx neutralizes the positive charges, which stimulates proton pumping and thus facilitates lumenal acidification. Indeed, we observed an initial ATP dependent acidification that was strongly enhanced upon addition of Cl− (Fig. 4c), demonstrating that the purified LDCVs exhibit a pronounced proton pumping activity. Furthermore, blocking of the V-ATPase with the inhibitor Bafilomycin reversed acidification, suggesting V-ATPase-specific acidification.

Stability of miR-375 stored in LDCVs

We have previously reported that LDCVs contain a variety of non-coding RNAs including miR-375, which is a dominant miRNA in LDCVs11. miR-375 is protected in the presence of RNase A as reported previously11. Here we tested how miR-375 can be stabilized after exocytosis. The presence of miRNAs in LDCVs are shown using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5) and the details of experiment set-up is described in Table 1. A synthesized Caenorhabditis elegans miRNA (cel-miR-39) as the spike-in control was added to normalize the RNA extraction efficiency. RNase A is not able to pass across the membranes so that it selectively degrades vesicle-free miRNA, but not vesicle-incorporated miRNA. RNase A degraded cel-miR-39, the spike-in control, but miR-375 remained intact, suggesting that miR-375 is incorporated in LDCVs11.

Table 1.

Tests for the stability of miR-375 stored in LDCVs.

| Treatment Reactions | Control | +RNase A | +TX-100 + RNase A | +TX-100 + Proteinase K + RNase A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vol. | Final Conc. | Vol. | Final Conc. | Vol. | Final Conc. | Vol. | Final Conc. | |

| LDCVs | 5 µl | 50 µg | 5 µl | 50 µg | 5 µl | 50 µg | 5 µl | 50 µg |

| Syn-cel-miR-39 | 5 µl | 0.5 pmol | 5 µl | 0.5 pmol | 5 µl | 0.5 pmol | 5 µl | 0.5 pmol |

| RNase-DNase Free PBS | 10 µl | 7.5 µl | 5.5 µl | 6 µl | ||||

| 10% TX-100 (vol/vol) | 2 µl | 1% | 2 µl | 1% | ||||

| Proteinase K(1 mg/ml) | 2 µl | 100 µg/ml | ||||||

| Protease inhibitor (2×) | 10 µl | |||||||

| RNase-DNase Free PBS | 5 µl | |||||||

| RNase A (100 µg/ml) | 2 µl | 10 µg/ml | 2 µl | 10 µg/ml | 4 µl | 10 µg/ml | ||

| RNase inhibitor (40 U/µl) | 0.5 µl | 1 U/µl | 0.5 µl | 1 U/µl | 1 µl | 1 U/µl | ||

| Final Volume | 20 µl | 20 µl | 20 µl | 40 µl | ||||

Next, we tested if miR-375 can be degraded by RNase A after Triton X-100 (TX-100) detergent treatment. TX-100 is a non-ionic detergent and completely disrupts the vesicle membrane. cel-miR-39 was mixed with LDCVs prior to TX-100 and then RNase A was applied after TX-100 treatment (Fig. 5a). We observed that miR-375 remains resistant to RNase A even in the presence of TX-100, whereas cel-miR-39 becomes degraded by RNase A (Fig. 5a). Then, we hypothesized that proteins might stabilize miR-375 and miR-375 was degraded by RNase A when proteinase K (PK) was included in TX-100-treated LDCVs (Fig. 5b). To confirm that proteins can protect miR-375, RNase A is applied after RNA extraction from protein complex using miRNeasy Mini Kit. Indeed, miR-375 is completely degraded by RNase A after proteins are removed; this result suggests that miR-375 is stabilized by proteins (Fig. 5c). Altogether, this protocol provides methods to test the presence of miRNAs in LDCVs and the stability of miR-375.

Discussion

This protocol obtains intact LDCVs from bovine adrenal medulla. These purified LDCVs can then be used to study their composition and content and to investigate their biochemical features such as proton pumping and SNARE-mediated membrane fusion as described in Fig. 4. More interestingly, purified LDCVs may be carriers in neurons and neuroendocrine cells that deliver miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs to extracellular fluid. miR-375 is stored in LDCVs and stabilized by protein complex (Fig. 5).

The protocol of LDCV isolation begins with mild homogenization of bovine adrenal medulla to disrupt the plasma membrane and release free LDCVs into the supernatant. These extracts are then loaded on a continuous sucrose density gradient ranging from 0.3 M to 2.0 M and centrifuged, resulting in the separation from other organelles. Mitochondria (marker, SDHA), late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (LEs/MVBs) and lysosomes (marker, LAMP-1), early endosomes (marker, EEA-1), endoplasmic reticulum (marker, calnexin), proteasomes (marker, Rpt-4), and peroxisomes (marker, catalase) are mostly removed, whereas LDCVs are highly enriched18. This fractionation method yields primarily mature LDCVs with 100~200 nm in diameter18 whereas immature LDCVs (identified here by the presence of VAMP-4) are also removed. Due to the vesicle maturation and condensation, mature LDCVs exhibit much higher buoyant density than immature LDCVs, and thus mature LDCVs are mainly enriched in the pellet18, which is used for functional studies. Mitochondria contaminations in different conditions of sucrose density gradient are presented in Fig. 3c; e.g., continuous sucrose gradient ranging from 0.3 M/1.8 M to 0.3 M/2.0 M and discontinuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M). Continuous sucrose gradient with 0.3 M/2.1 M was also tried to isolate LDCVs, but LDCVs were barely isolated with very little pellet (data not shown); LDCVs are not able to migrate through high density sucrose solutions into the pellet due to high sucrose concentration in case of 0.3 M/2.1 M sucrose gradient, thereby leading to extremely low yield of LDCVs. We tested different sucrose gradient ranging from 0.3 M/1.6 M to 0.3 M/2.1 M and mitochondria are mostly removed in our protocol, when we use continuous sucrose gradient (0.3 M/2.0 M) (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, our previous overlay assay shows ~95% purity of isolated LDCVs11, supporting that most mitochondria are removed and isolated LDCVs are highly pure.

LDCVs contain a variety of miRNAs, which are released by LDCV exocytosis11. A new paradigm suggests that secreted miRNAs constitute novel neuromodulators by regulating cell−to−cell communication that include gene silencing and cellular signaling. We propose ‘ribomone (ribonucleotide + hormone)’, because miRNAs are stored inside the vesicles and released by active vesicle fusion in response to stimulation so that secreted miRNAs might regulate cell−to−cell communication including gene silencing and cellular signaling. Our data provide evidence that secreted miR-375 can be stabilized by protein complex against RNase A, implying that secreted miRNAs might function a physiological role for long-term with high stability.

In conclusion, this protocol improves the purity of LDCVs by combining differential and continuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. This technique can be useful in research on the biological functions of LDCVs, including vesicle fusion, vesicle acidification, monoamine transport, and the functions of miRNAs stored in LDCVs. The purification of LDCVs also contributes to study psychiatric and mental disorders, which might be caused by imbalance of serotonin, adrenaline, and dopamine, because LDCVs store most of monoamine transmitters such as serotonin, adrenaline, and dopamine, which are directly linked to psychiatric and mental disorders.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All reagents are available from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated and should be of analytical grade or higher. RNase A and RNase inhibitor, RiboLock were from Thermo Scientific. Protease inhibitor, cOmplete ULTRA Tablets, Mini, EDTA-free EASYpack was from Roche. Antibodies against VAMP-2 and DBH were from Synaptic Systems (Göttingen, Germany). Antibodies against SDHA was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Lipids were from Avanti (Alabaster, AL). RNA isolation kit, miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 217004). cDNA synthesis kit, miScript RT II kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 218161). Synthetic Caenorhabditis elegans miR-39 (syn-cel-miR-39), spike-in control (Qiagen, cat. no. 219610). Synthetic miR-375 (Syn-bta-miR-375), miScript miRNA Mimic (Qiagen, cat. no. 219600). Primer for cel-miR-39, UCACCGGGUGUAAAUCAGCUUG (Qiagen cat. no. MS00019789). Primer for bta-miR-375; UUUUGUUCGUUCGGCUCGCGUGA (Qiagen cat. no. MS00053865). miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 218073).

LDCV isolation

Fresh bovine adrenal glands were obtained from a local slaughterhouse. After trimming away the cortex and fat, the medullae were minced with a scissor in 300 mM sucrose buffer (300 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 adjusted with KOH) and then homogenized using a cooled a Glass-Teflon homogenizer at 1,000 rpm (H, homogenate). PMSF (200 μM) was added to prevent protein degradation. All subsequent steps were carried out at 0°–4 °C. After centrifugation at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, the pellet containing nuclei and cell debris (P1) was discarded. The supernatant (S1) was further centrifuged (12,000 g, 15 min, 4 °C), followed by the additional cycle of resuspension and centrifugation for washing step. The resulting pellet (P2, crude LDCV fraction) was resuspended in 300 mM sucrose buffer and loaded on top of a continuous sucrose gradient (from 300 mM to 2.0 M) to remove other contaminants including mitochondria. LDCVs were collected from the pellet after centrifugation at 110,000 g for 60 min in a Beckman SW 41 Ti rotor and resuspended with the buffer (120 mM K-glutamate, 20 mM K-acetate, 20 mM HEPES.KOH, pH 7.4). The fraction directly on top of the pellet was removed and the pellet was only resuspended in order to purify mature LDCVs. The purified LDCVs can be snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored for several months at −80 °C. Make small aliquots of LDCV samples to reduce damage by freeze-thaw cycles. Size distribution of purified LDCVs was determined using dynamic light scattering (NanoPlus DLS, Particulate Systems).

Vesicle fusion assay

Vesicle fusion reactions were performed at 37 °C. 50 μg of purified LDCVs and 10 μl of plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes were mixed in 1 ml of buffer containing 120 mM K-glutamate, 20 mM K-acetate, 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4). Plasma membrane-mimicking liposomes contained the stabilized Q-SNARE complex23. Fluorescence dequenching signal was measured with wavelengths of 460 nm for excitation and 538 nm for emission. Fluorescence values were normalized as the percentage value of the maximum donor fluorescence induced by 0.1% Triton X-100 detergent treatment at the end of experiments. Control represents basal fusion without any treatment.

Immunoblotting

Glycerol-containing gels with 0.1% SDS were used to separate low molecular weight proteins with high resolution. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and then blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% tween-20). Proteins as indicated in manuscripts were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Vesicle acidification assay

Acidification measurements were performed as described previously using acridine orange (AO, Molecular Probes) as a pH sensitive dye25. Changes in absorbance at 492 nm (ΔAU) were monitored in an Aminco dual-wavelength spectrophotometer using absorbance at 530 nm as reference, giving a read-out of lumenal pH changes26. Usually, 600–650 µl buffer (300 mM glycine, 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.3, and 2 mM MgSO4) were mixed in a 1 ml glass cuvette with purified LDCVs containing 10 µM AO and measured at 32 °C. The measurements were performed in 300 mM glycine, 10 mM MOPS, 2 mM MgSO4, pH 7.3 buffer.

Quantification of miR-375 using qRT-PCR

Several reactions to test the stability of miR-375 in the presence of RNase A, TX-100, and/or proteinase K was described in details in Table 1. 0.5 pmol of syn-cel-miR-39 was incubate with ~50 µg of LDCVs for 5 min at RT (~22 °C). 1% (vol/vol) TritonTm X-100 (TX-100) was treated with LDCVs for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 10 µg/ml (final concentration) of RNase A was applied for 15 min in the presence or absence of TX-100. If RNase A is used, then 1 U/µl RNase inhibitor was added for 5 min to stop the RNase activity. In cases of proteinase K treatment 2 µl of 100 µg/ml of proteinase K was applied for 30 min. A protease inhibitor cocktail was added for 5 min to stop proteinase activity. Then 10 µg/ml RNase A was applied to degrade RNA.

Total RNA from LDCV samples with different treatments (Table 1) was isolated using miRNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated RNAs were transferred into 0.2 ml PCR Strip tubes, then cDNA syntheses was performed using miScript RT II kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 5X miScript HiSpec buffer was used to prepare the reaction mix. miR-375 and cel-miR-39 were quantified using qRT-PCR according to miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit protocol. For miRNA quantification of miR-375 and cel-miR-39, a standard curve should be established using syn-bta-miR-375 and syn-cel-miR-39. For this task, serial dilutions (0.02 pM to 2 nM) of syn-bta-miR-375 and syn-cel-miR-39 were prepared. qRT-PCR analysis was performed using Bio-Rad, CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System. Crossing point-PCR-cycle (Cp) values were used to plot the standard curve and to analyze the concentraction of miR-375 stored in LDCVs and cel-miR-39, which is a spike-in control.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by EMBO Installation Grant (IG Project Number 3265 to Y.P.) and Qatar Biomedical Research Institute (Project Number SF 2019 004 to Y.P.).

Author contributions

Y.B., M.G., Y.P. purified LDCVs and performed experiments. Y.B. performed RNA isolation and qRT-PCR for miRNA quantification. J.P. carried out the acidification assay. R.J., Y.P. designed, collected, and analyzed data. Y.B., R.J., Y.P. wrote the manuscript and all authors read and provided their comments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 4, where the label of the X-axis ‘Size (nm)’ in panel (a) was incorrectly given as ‘Time (min)’.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/6/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-022-21361-7

Contributor Information

Reinhard Jahn, Email: rjahn@gwdg.de.

Yongsoo Park, Email: ypark@hbku.edu.qa.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-64486-3.

References

- 1.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudhof TC. Neurotransmitter release: the last millisecond in the life of a synaptic vesicle. Neuron. 2013;80:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Camilli P, Jahn R. Pathways to regulated exocytosis in neurons. Annual review of physiology. 1990;52:625–645. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park Y, Kim KT. Short-term plasticity of small synaptic vesicle (SSV) and large dense-core vesicle (LDCV) exocytosis. Cellular signalling. 2009;21:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin TF. The molecular machinery for fast and slow neurosecretion. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:626–632. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heuser, J. E. a. R.T. S. Structure of the Synapse. Comprehensive Physiology. 261 (Wiley, 2011).

- 7.Fung MM, Viveros OH, O’Connor DT. Diseases of the adrenal medulla. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008;192:325–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich ME, Evinger M, Regunathan S, Teitelman G. Mammalian adrenal chromaffin cells coexpress the epinephrine-synthesizing enzyme and neuronal properties in vivo and in vitro. Dev Biol. 1994;163:480–490. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkler H. The adrenal chromaffin granule: a model for large dense core vesicles of endocrine and nervous tissue. J Anat. 1993;183(Pt 2):237–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crivellato E, Nico B, Ribatti D. The chromaffin vesicle: advances in understanding the composition of a versatile, multifunctional secretory organelle. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:1587–1602. doi: 10.1002/ar.20763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gumurdu A, et al. MicroRNA exocytosis by large dense-core vesicle fusion. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45661. doi: 10.1038/srep45661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park Y. MicroRNA Exocytosis by Vesicle Fusion in Neuroendocrine Cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:355. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillarp NA, Lagerstedt S, Nilson B. The isolation of a granular fraction from the suprarenal medulla, containing the sympathomimetic catechol amines. Acta Physiol Scand. 1953;29:251–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1953.tb01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith AD, Winkler H. A simple method for the isolation of adrenal chromaffin granules on a large scale. Biochem J. 1967;103:480–482. doi: 10.1042/bj1030480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegrzyn JL, et al. Proteomics of dense core secretory vesicles reveal distinct protein categories for secretion of neuroeffectors for cell-cell communication. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5002–5024. doi: 10.1021/pr1003104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillarp NA. Catecholamines: mechanisms of storage and release. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh) 1960;Suppl 50:181–185. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.XXXIVS181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris SJ, Schultens HA, Schober R. An osmometer model for changes in the buoyant density of chromaffin granules. Biophys J. 1977;20:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85535-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park Y, et al. Controlling synaptotagmin activity by electrostatic screening. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:991–997. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plattner H, Artalejo AR, Neher E. Ultrastructural organization of bovine chromaffin cell cortex-analysis by cryofixation and morphometry of aspects pertinent to exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1709–1717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, T., Gondre-Lewis, M. C., Arnaoutova, I. & Loh, Y. P. Dense-core secretory granule biogenesis. Physiology (Bethesda)21, 124-133, doi:21/2/124[pii]10.1152/physiol.00043.2005 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Meldolesi J, Chieregatti E, Luisa Malosio M. Requirements for the identification of dense-core granules. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park Y, et al. Synaptotagmin-1 binds to PIP(2)-containing membrane but not to SNAREs at physiological ionic strength. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:815–823. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pobbati AV, Stein A. & Fasshauer, D. N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly promotes rapid membrane fusion. Science. 2006;313:673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struck DK, Hoekstra D, Pagano RE. Use of resonance energy transfer to monitor membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4093–4099. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preobraschenski J, Zander JF, Suzuki T, Ahnert-Hilger G, Jahn R. Vesicular glutamate transporters use flexible anion and cation binding sites for efficient accumulation of neurotransmitter. Neuron. 2014;84:1287–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hell JW, Maycox PR, Jahn R. Energy dependence and functional reconstitution of the gamma-aminobutyric acid carrier from synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2111–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39947-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming PJ, Kent UM. Cytochrome b561, ascorbic acid, and transmembrane electron transfer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1173S–1178S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1173s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park Y, et al. alpha-SNAP interferes with the zippering of the SNARE protein membrane fusion machinery. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:16326–16335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.556803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.