Abstract

BACKGROUND

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are widely used for treatment of many advanced malignancies. Lower gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, such as diarrhea and colitis, are common, but upper GI side effects are rarely reported. Consequently, the correct treatment of upper GI adverse events has been less frequently described.

CASE SUMMARY

We describe a case of a 16-year-old woman with stage IIIb malignant melanoma treated with adjuvant monotherapy using Nivolumab. The patient developed severe gastritis after six series of Nivolumab with weight loss, nausea, and vomiting. There was no effect of intravenous steroids, but the patient´s condition resolved after administration of Infliximab.

CONCLUSION

This case report supports the same treatment for gastritis as for colitis, which is in line with current guidelines.

Keywords: Gastritis, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Nivolumab, Case report, Immune-related adverse events, Infliximab

Core tip: Lower gastrointestinal side effects, such as diarrhea and colitis, caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors are well described, but upper gastrointestinal side effects are less frequently reported. Here, we present a case of severe corticosteroid refractory gastritis induced by Nivolumab. The patient’s symptoms resolved after administration of Infliximab. The treatment was in line with current guidelines for treatment of gastritis.

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have shown to be effective drugs against various malignancies and are now standard of care for several types of advanced tumors. Current ICIs release some of the brakes in the immune system and thereby reinforce T-cell destruction of tumor cells by blocking regulatory cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4, programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1), or the PD-1 ligand[1]. This may also lead to several immune-related adverse events (irAE), especially during Ipilimumab/Nivolumab double therapy[2].

As the use of ICIs becomes more widespread, the knowledge of the irAEs of these drugs is increasingly important. The most common side effects are skin reactions and lower gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, and treatment of these reactions have been thoroughly described[3,4]. However, only very few cases of patients with upper GI-tract immune mediated reactions have been reported in the literature and these have mainly been managed with prednisone monotherapy[5-7].

Here we present a patient who developed a severe steroid refractory gastritis after Nivolumab monotherapy that required biological treatment with Infliximab.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 16-year-old woman treated with adjuvant Nivolumab presented with vomiting, nausea, and weight loss.

History of present illness

The patient was diagnosed with stage IIIb malignant melanoma (T3bN1aM0). Both the primary melanoma and sentinel lymph node were radically removed. The patient was offered adjuvant treatment with Nivolumab (anti-PD-1), with 6 mg/kg administered every 4 wk[8]. Initially, the patient tolerated the treatment well with only a small rise in plasma alanine transaminase compatible with a grade 1 hepatitis[9]. An ultrasound examination of the liver was performed without any abnormalities observed.

After the sixth series of Nivolumab, the patient presented with anorexia, vomiting, nausea, upper abdominal pain, and a weight loss of approximately 3 kg (Table 1). The patient was admitted and received a short low-dose prednisone treatment for 4 d (40 mg methylprednisolone on the first day followed by 25 mg prednisone for 3 d) with a little initial symptomatic effect. The patient was discharged after 3 d, but readmitted 10 d later because of worsening of her symptoms with dehydration, vomiting, and stomach pain.

Table 1.

Timeline

| Time | Event | Findings |

| June 2018 | Removal of mole on the right thigh at the general practitioner | Pathology showed malignant melanoma, 2.1 mm. Level IV |

| August | Re-excision of malignant melanoma and sentinel node biopsy | Stage IIIb malignant melanoma. (No open protocol for adjuvant treatment) |

| September | PET-CT | No metastases |

| December | Multidisciplinary team-conference | Referred to the oncology department |

| January 2019 | Started adjuvant Nivolumab treatment | |

| March | Nausea and stomach pain | Grade 1 hepatitis (ALT 129 U/L) |

| April | Ultrasound of liver because of elevated ALT | Normal |

| May | Decline in ALT (ALT 47 U/L), 6th dose of Nivolumab | |

| June 21-24 | First admission for 3 d with nausea, stomach pain, and vomiting; Cerebral MRI | Short prednisone treatment with initial effect. No brain metastasis |

| July 1 | PET-CT (Figure 1) | FDG-uptake in the gastric wall |

| July 3 | Second admission with vomiting, stomach pain, and nausea | ALT 85 U/L, albumin 23 g/L |

| July 4 | EGD and EUS (Figure 2); Initiated methylprednisolone 80 mg iv. | Gastritis. Erythematous mucosa with severe, fibrinous erosions. Acute and chronic inflammation |

| July 10 | First dose Infliximab | |

| July 11 | Discharged; continued prednisone | |

| July 18 | Initiated tapering of prednisone | |

| July 24 | Second dose Infliximab | |

| August 8 | EGD | Slight to moderate gastritis without ulcerations and fibrinous membranes. Improvement compared to the first EGD |

| September 17 | PET-CT (Figure 4) | No FDG uptake in the gastric wall |

| September 26 | Discontinued prednisone |

ALT: Alanine transaminase; PET-CT: Positron emission tomography with computed tomography; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; FDG: Fluorodeoxyglucose.

History of past illness

The patient had no comorbidities. There was no history of prior gastroenterological symptoms.

Personal and family history

The patient did not smoke or consume alcohol. There was no noteworthy family medical history.

Physical examination

Physical examination showed a pale and dehydrated patient with a weight loss of 3 kg. The abdomen was soft but revealed tenderness in the epigastrium.

Laboratory examination

Blood tests showed a slight elevation in alanine transaminase (91 U/L; reference range 10-45 U/L) compatible with grade 1 hepatitis. Additional blood tests, including thyrotropin and cortisol, were in normal range.

Imaging examination

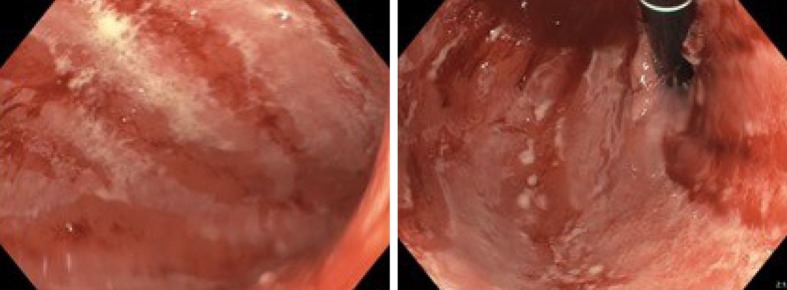

At first admission after the sixth Nivolumab dose, a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging was performed to rule out metastases to the brain. In the following week a positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed. Abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was demonstrated in the gastric wall, especially around the corpus antrum (Figure 1). Linitis plastica was suspected and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with supplementary endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed. The EGD showed a vulnerable mucosa with a white fibrine-like membrane in the antrum, corpus, and fundus. EUS demonstrated increased thickening of the gastric wall to 13 mm. No focal malignant lesions were suspected, and the finding was interpreted as inflammation. Macroscopically, the mucosa was erythematous with severe fibrinous erosions (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The first positron emission tomography with computed tomography after the patient presented with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. The scan showed abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the gastric wall, especially around the corpus antrum.

Figure 2.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy before treatment. The gastric wall was erythematous with severe fibrinous erosions of the mucosa.

Pathological findings

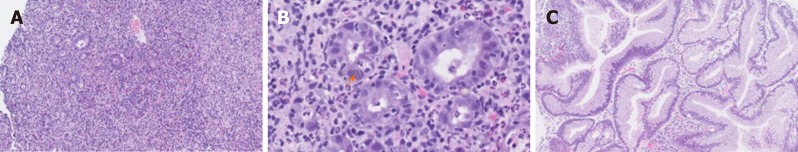

The initial endoscopical examination was compatible with chronic active pangastritis (Figure 3A and B). Biopsies from fundus, corpus, and antrum ventriculi showed severe changes with ulceration, crustation, and only scattered glands. The glandular epithelium showed very reactive changes, apoptosis, neutrophilic inflammation, and crypt abscesses, as well as intraepithelial lymphocytosis (45 per 100 epithelial cells). The lamina propria showed a diffuse, full thickness lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Epithelial granulomas, thickened subepithelial collagen layer, or prominent eosinophils, were not observed. There were no signs of malignancy, CMV infection, or Helicobacter pylori. Epstein Barr virus serology showed positive Epstein Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG corresponding with a previous infection.

Figure 3.

Imaging of histopathology. A, B: Diffuse chronic active pangastritis with ulceration and only scattered glands. Neutrophilic inflammation and crypt abscesses increased intraepithelial lymphocytes and apoptosis (arrow) (A: 100 ×; B: 400 ×); C: Regenerated epithelium with focal acute inflammation (100 ×).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The inflammation was interpreted as a severe immune related side effect to the Nivolumab treatment.

TREATMENT

Upon the second admission, the patient was treated daily with high-dose steroid (80 mg methylprednisolone) intravenously along with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI; 40 mg) with only minor relief of her symptoms. She still presented with vomiting and nausea, and had trouble eating and drinking sufficiently. Albumin levels deteriorated to 23 g/L (reference range 37-48 g/L). Because of insufficient improvement on the intravenous methylprednisolone, the patient received Infliximab (5 mg/kg) 6 d after the initial steroid dose. She continued oral high dose steroid (100 mg prednisone) and PPI, which was briefly increased to 40 mg twice daily. Her symptoms improved temporarily for a week after receiving Infliximab, but because of continued nausea and light vomiting, she received a second dose of Infliximab 2 wk after receiving the first dose. Both PPI and prednisone were tapered during follow up.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

A new EGD was performed 4 wk after the patient received the first dose of Infliximab. This showed improvement with slight to moderate gastritis, but without ulcerations and fibrinous membranes. In the antrum area, vulnerable mucosa was observed when touching with the endoscope. The EUS showed a stomach wall measuring 5-8 mm, but still 13 mm in the fundus. The findings were interpreted as improvement compared to the first EGD but still with some inflammatory changes remaining after the two Infliximab doses. Accordingly, the histology was without ulceration and regenerated mucosa (Figure 3C). The glandular epithelium showed mild to moderate chronic active activity. Acute inflammation with neutrophilic inflammation was seen in areas. There was still intraepithelial lymphocytosis (20 lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells), but only few apoptotic cells were found. The lamina propria still showed increased lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, although less pronounced full thickness. There was no evidence of epithelial granulomas, thickened subepithelial collagen layer or prominent eosinophils. Likewise, there were no signs of malignancy or Helicobacter pylori.

The symptoms of the patient gradually improved under continuous tapering of steroids, which was discontinued after approximately 3 mo. There has been no need for a third dose of Infliximab to this point. The first status PET was performed 10 wk after the first Infliximab treatment and 3.5 mo after receiving the last Nivolumab dose and showed normalization with no fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the gastric wall (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The second positron emission tomography with computed tomography performed 10 wk after the first Infliximab administration. This showed a normal gastric wall with no fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of severe corticosteroid refractory pangastritis, without Crohn-like pattern, in a young woman after receiving adjuvant Nivolumab for high-risk melanoma.

GI irAEs, such as colitis with diarrhea, are well known irAEs for all ICIs. Nivolumab monotherapy is less toxic than Ipilimumab alone or when used in combination therapy[2,10]. The rate of grade 3/4 GI tract side effects caused by Nivolumab treatment alone is around 1%-2%[2,3]. The incidence of diarrhea is reported to be 19%[9]. Upper GI-tract toxicity such as nausea and vomiting, as presented in this case, are much less common[10].

In guidelines, the recommended treatment for gastritis grade 2 or higher is similar to the management of colitis[9,11] with corticosteroids at 1-2 mg/kg bodyweight. If there has been no sufficient effect within 3-5 d, biological treatments like Infliximab or Vedolizumab are recommended[4,9].

Only a few case reports in the literature showed gastritis as a side effect to ICIs. Two of the reported cases had been treated with Nivolumab[5,12], in one of the cases symptoms first presented 6 mo after the treatment[5]. Another was treated with Ipilimumab, but had previously been treated with Nivolumab[6]. Others were treated with Pembrolizumab[13], Ipilimumab monotherapy, or Ipilimumab and Nivolumab combination therapy[7]. One case in Johncilla et al[7] received Nivolumab monotherapy but developed only a discrete gastritis together with colitis. In one case, coexistence of Helicobacter pylori was observed[6].

In Johncilla et al[7], 8 of the 12 patients were treated with steroid monotherapy, 2 patients received Infliximab treatment and 2 patients were not in need of any treatment. Both the patients in need of Infliximab also had concurrent colitis. The paper did not highlight whether it was colitis or gastritis, which necessitated Infliximab therapy. In Boike et al[5], Nishimura et al[6] and Calugareanu et al[12], the patients were treated with intravenous corticosteroids and PPI alone. In another study, no information was given as to whether corticosteroid was needed[13].

Johncilla et al[7], describes the histologic pattern of gastric irAEs and possible differential diagnosis. The most common pattern seen in the untreated form was a diffuse chronic active gastritis. Remaining patients showed a focal enhancing gastritis pattern similar to the changes seen in Crohn’s disease. The two patients that received Infliximab therapy for resolution of their symptoms had both developed a Crohn’s-like pattern. In our patient, we found ulceration and a severe diffuse chronic active pangastritis without evidence of granulomatous inflammation or focal enhancing gastritis, reminiscent of the histopathology seen in Crohn’s disease. However, with such pronounced changes it may be difficult to distinguish between the two.

Even though upper GI tract symptoms are rarely reported during ICI treatment, signs of inflammation in the upper GI-tract might be present. A study on enterocolitis in 39 patients treated with anti-T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4 antibodies showed that 9 of the 22 patients, in which an EGD was performed, had coexistent gastritis. However, it was not reported if these patients showed any symptoms of gastritis[11]. Similar results were found in another study on GI irAEs in 20 patients treated with an anti-PD-1 antibody[14]. In this study 13 of the patients had an abnormal EGD. The main findings were mucosal erythema, but in two of the cases, the EGD showed necrotizing gastritis.

A recent retrospective single-center study[15] investigated patients who developed upper GI symptoms in need for EGD within 6 mo after having received ICIs. This was only present in 60 out of 4716 cases, 23 of which required hospitalization. Fourteen patients were treated with Infliximab or Vedulizumab, but only one of these patients had isolated upper GI tract involvement. The remainder had concurrent lower GI tract involvement.

In this present case report the patient was treated for severe gastritis according to the guidelines for colitis with initially corticosteroids intravenously and afterwards Infliximab because of insufficient effect of the corticosteroids alone. On this treatment, the patient’s clinical symptoms resolved completely and on PET-CT within three and a half months after the last Nivolumab dose.

CONCLUSION

Severe gastritis, as presented in this case, is a much rarer adverse event for ICIs, especially Nivolumab monotherapy, than lower GI symptoms like colitis. However, the knowledge and awareness of this complication is important in all combinations of ICIs. Patients with severe ICI induced gastritis deteriorates very fast due to insufficient nutrition. The usage of ICIs expands and in order to give proper treatment for immune mediated gastritis in time, further studies of the histopathology and response to treatment are required. No controlled clinical studies have been published on the management of upper GI tract symptoms. However, current guidelines recommend timely biological treatment as for ICI induced colitis. The case report supports this recommendation.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Peer-review started: February 7, 2020

First decision: February 27, 2020

Article in press: April 18, 2020

P-Reviewer: Jia J, Moustaki M, Vieth M S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Helene Hjorth Vindum, Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus 8200, Denmark. helra9@rm.dk.

Jørgen S Agnholt, Department of Gastroenterology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus 8200, Denmark.

Anders Winther Moelby Nielsen, Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus 8200, Denmark.

Mette Bak Nielsen, Department of Pathology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus 8200, Denmark.

Henrik Schmidt, Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus 8200, Denmark.

References

- 1.Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K, Bhise K, Kashaw SK, Iyer AK. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha M, Correia de Sousa J, Salgado M, Araújo A, Pedroto I. Management of Gastrointestinal Toxicity from Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2019;26:268–274. doi: 10.1159/000494569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, Aberle J, Bachmann O, Grünwald V, Kähler KC, Loquai C, Reinmuth N, Steins M, Zimmer L, Sendl A, Gutzmer R. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, Jordan K ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv264–iv266. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boike J, Dejulio T. Severe Esophagitis and Gastritis from Nivolumab Therapy. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e57. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura Y, Yasuda M, Ocho K, Iwamuro M, Yamasaki O, Tanaka T, Otsuka F. Severe Gastritis after Administration of Nivolumab and Ipilimumab. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11:549–556. doi: 10.1159/000491862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johncilla M, Grover S, Zhang X, Jain D, Srivastava A. Morphological spectrum of immune check-point inhibitor therapy-associated gastritis. Histopathology. 2020;76:531–539. doi: 10.1111/his.14029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL, Dalle S, Schenker M, Chiarion-Sileni V, Marquez-Rodas I, Grob JJ, Butler MO, Middleton MR, Maio M, Atkinson V, Queirolo P, Gonzalez R, Kudchadkar RR, Smylie M, Meyer N, Mortier L, Atkins MB, Long GV, Bhatia S, Lebbé C, Rutkowski P, Yokota K, Yamazaki N, Kim TM, de Pril V, Sabater J, Qureshi A, Larkin J, Ascierto PA CheckMate 238 Collaborators. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Ernstoff MS, Gardner JM, Ginex P, Hallmeyer S, Holter Chakrabarty J, Leighl NB, Mammen JS, McDermott DF, Naing A, Nastoupil LJ, Phillips T, Porter LD, Puzanov I, Reichner CA, Santomasso BD, Seigel C, Spira A, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wang Y, Weber JS, Wolchok JD, Thompson JA National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Rahman O, ElHalawani H, Fouad M. Risk of gastrointestinal complications in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:1213–1227. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marthey L, Mateus C, Mussini C, Nachury M, Nancey S, Grange F, Zallot C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Rahier JF, Bourdier de Beauregard M, Mortier L, Coutzac C, Soularue E, Lanoy E, Kapel N, Planchard D, Chaput N, Robert C, Carbonnel F. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:395–401. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cǎlugǎreanu A, Rompteaux P, Bohelay G, Goldfarb L, Barrau V, Cucherousset N, Heidelberger V, Nault JC, Ziol M, Caux F, Maubec E. Late onset of nivolumab-induced severe gastroduodenitis and cholangitis in a patient with stage IV melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:1005–1013. doi: 10.2217/imt-2019-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yip RHL, Lee LH, Schaeffer DF, Horst BA, Yang HM. Lymphocytic gastritis induced by pembrolizumab in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018;28:645–647. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins M, Michot JM, Danlos FX, Mussini C, Soularue E, Mateus C, Loirat D, Buisson A, Rosa I, Lambotte O, Laghouati S, Chaput N, Coutzac C, Voisin AL, Soria JC, Marabelle A, Champiat S, Robert C, Carbonnel F. Inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases associated with PD-1 blockade antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2860–2865. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang T, Abu-Sbeih H, Luo W, Lum P, Qiao W, Bresalier RS, Richards DM, Wang Y. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and associated endoscopic and histological features in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:538–545. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1594356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]