Abstract

Objective:

Most studies linking physical victimization and substance use have focused on concurrent or temporally proximal associations, making it unclear whether physical victimization has a sustained impact on substance use problems. We examined the long-term associations between adolescent physical victimization and symptoms of substance use disorders in adulthood, controlling for intermediating victimization during young adulthood and several control variables.

Method:

Data were obtained from the Monitoring the Future Study (N = 5,291). Women and men were recruited around age 18 and surveyed biennially through age 30, and again at 35. Past-year physical victimization (threatened physical assaults, injurious assaults) was measured regularly from age 18 to 30. Alcohol and cannabis use symptoms (e.g., withdrawal, tolerance) were assessed at age 35. Controls were measured in adolescence (e.g., prior substance use) and young adulthood (e.g., marriage). Interactions examined whether associations varied by sex.

Results:

When we controlled for adolescent substance use, adolescents who were threatened with injury or who sustained physical injuries as a result of violence had more alcohol use symptoms at age 35 than nonvictims. However, when victimization during young adulthood was statistically accounted for, only victimization during young adulthood was associated with age-35 alcohol use symptoms. The effects of young adult victimization, but not adolescent victimization, were stronger for women. Victimization was mostly unrelated to age-35 cannabis use symptoms.

Conclusions:

Adolescents who are threatened with physical assaults or injured by physical assaults have significantly more alcohol use symptoms in their mid-30s than nonvictimized adolescents, but these associations are completely explained by subsequent victimization during young adulthood.

More than a million adolescents and young adults (18–34 years old) are victims of violent crimes in the United States every year (Truman & Langton, 2015). Victims of violence are at heightened risk for a variety of psychological and psychosocial problems, and one consistently studied correlate of victimization is substance use (Fagan et al., 2015; Hedtke et al., 2008; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2011; Madruga et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2004; Taylor & Kliewer, 2006; Vermeiren et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2013; Zinzow et al., 2009). Although many studies have examined the concurrent or short-term associations between victimization during adolescence and substance use, very few studies have examined the long-term impact of victimization during adolescence. Furthermore, many existing longitudinal studies have been unable to control for all potential explanatory factors, such as participants’ pre-victimization substance use and subsequent victimization during early young adulthood.Using a U.S. national sample of more than 5,000 men and women who were followed for almost 20 years, the present study builds on prior work by examining the extent to which personally experienced physical victimization during adolescence was associated with symptoms of substance use disorder during the mid-30s, net of several potential confounding variables and victimization during early young adulthood.

Extracting broadly from the basic tenets of general strain theory (Agnew, 1992, 2001; Agnew & White, 1992) and the self-medication hypothesis, victimization may lead to substance use problems because victims of violence may experience psychological (e.g., anger, anxiety) and physical pain in response to victimization, and victims may self-medicate their pain with drugs and alcohol (Lin et al., 2011; Taylor & Kliewer, 2006; Windle & Windle, 1996). Furthermore, because of the unique developmental features of adolescence, teens who experience victimization may be especially vulnerable to future substance use problems. Adolescence is a period of pervasive neurological, cognitive, and socioemotional changes (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009; Steinberg, 2005). As a result of these changes, adolescents are more responsive to stress and rewards (particularly social stressors and rewards) than both children and adults (Steinberg, 2005). This heightened sensitivity suggests that victimization may be particularly stressful and isolating for adolescents. Victimization may cause adolescents to withdraw from or fear others, which, in turn, may cause them to develop a coping style that includes self-medication with drugs and/or alcohol instead of a more adaptive coping (e.g., seeking support from others). Furthermore, given that brain regions responsible for self-regulation and reward processing—systems that have been implicated in addiction and substance dependence (Goldstein & Volkow, 2011; Koob & Le Moal, 2008)—undergo significant restructuring during adolescence (Blakemore, 2012; Steinberg, 2005), there may be unique biological vulnerabilities during adolescence.

Support for the link between adolescent victimization and substance use has been found in both cross-sectional (Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2011; Madruga et al., 2011; Vermeiren et al., 2003; Zinzow et al., 2009) and short-term (1–3 year) longitudinal studies (Fagan et al., 2015; Hedtke et al., 2008; Pinchevsky et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2004; Taylor & Kliewer, 2006; Wright et al., 2013). Although most studies suggest that the path of influence is from victimization to substance use, some studies have reported evidence of the reverse pathway and/or bidirectional associations (Mrug & Windle, 2009; Thompson et al., 2008). Thus, it is crucial to control for initial levels of substance use and to examine the impact of victimization with prospective, longitudinal data. Unfortunately, only a couple of studies have examined the long-term associations between adolescent victimization and adult substance use problems (e.g., Menard et al., 2015; Thompson et al., 2008), and these studies have produced somewhat conflicting findings.

For example, Menard et al. (2015) found that a general measure of victimization during adolescence was associated with higher odds of cannabis use in adulthood. However, that study did not examine alcohol use, and the cannabis outcome included any use, which is a relatively low threshold and might include use that is more casual and infrequent. In addition, that study did not examine the extent to which repeat victimization, or subsequent victimization, during young adulthood accounted for a potential link between adolescent victimization and adult cannabis use. In contrast to other prior work on the topic, Thompson et al. (2008) found that violent victimization during adolescence was generally not associated with alcohol use problems 7 years later, although they found concurrent and short-term associations between victimization and alcohol use. Unfortunately, the Thompson et al. (2008) study did not examine the association between victimization and cannabis use. The study also was limited because it had only three assessments: an initial interview, a 1-year follow up, and a 7-year follow up. In addition, neither of these studies included crucial confounding variables, such as assessments of participants’ own interpersonal aggression and other antisocial and illegal behavior. It is important to include measures of participants’ own externalizing and aggressive behaviors to control for the participants’ propensity to self-select risky settings that may facilitate both substance use and victimization.

One additional limitation in prior work is that victimization has been defined broadly and the definition tends to vary greatly from study to study. For example, some studies combine experienced and witnessed violence, whereas others combine violent and nonviolent (e.g., property) victimization, and/or injurious and noninjurious violence. This is a significant limitation given that different types of victimization during adolescence are likely to have unique effects on substance use (Pinchevsky et al., 2014; Tharp-Taylor et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2013). Given that physical assaults are the most common victimization experience among adolescents (Finkelhor et al., 2005, 2009a), it is important to understand the unique impact of physical victimization. In addition, because some physical assault victims may incur injuries whereas others may just be threatened with injuries, it is important to separate injurious and threatened assaults. Indeed, the nature of the impact of being a physical assault victim likely depends on whether the victim actually sustains physical injuries, or whether he or she is led to believe that he or she might—at some unknown time in the future—be injured. Injurious assaults may cause both physical and psychological pain, whereas threatened assaults may cause excessive worry and rumination and lead to sustained periods of psychological distress. Importantly, no prior study has made this distinction; thus, the unique impacts of threatened and injurious physical violence are essentially unknown. Identifying these effects is important for both theoretical and practical (e.g., screening instruments, interventions/treatment) reasons.

Present study

The present study was designed to overcome the limitations in prior work. We examined whether personally experienced threatened and injurious physical assaults during adolescence were associated with age-35 alcohol use symptoms and age-35 cannabis use symptoms using a sample of more than 5,000 men and women who were followed from age 18 to 35. We separated adolescent physical victimization into threatened physical assaults and injurious physical assaults to examine the unique impact of each type of victimization. Given that prior studies have found that the impact of victimization might vary for men and women (Begle et al., 2011; Gewirtz & Edleson, 2007; Menard et al., 2015; Simpson & Miller, 2002; Thompson et al., 2008), we examined sex interactions in the final step. Because alcohol and cannabis problems might have unique etiologies (Kendler et al., 2003; Schulenberg et al., 2016), we examined these substances separately.

We controlled for several potentially confounding variables measured during adolescence and young adulthood. First, we controlled for adolescent substance use to control for the possibility that substance use problems may precede victimization. In addition, we controlled for sex, given that males are more likely to be physically assaulted and experience violent victimization (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2008) and have higher rates of substance use problems (Schulenberg et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2008) than females. We also controlled for other demographic factors that have been consistently correlated with victimization and/or substance use, such as race, socioeconomic background, and urbanicity (Atav & Spencer, 2002; Donnermeyer & Scheer, 2001; Falck et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2008; Martino et al., 2008; Murphy, 2018; Mykota & Laye, 2015; Schulenberg et al., 2016). In addition, we controlled for adolescents’ externalizing behavior, because youths’ own antisocial and aggressive behavior may provoke, precede, or co-occur with victimization (Begle et al., 2011; Jennings et al., 2012; Kingery et al., 1992; Nansel et al., 2003) and externalizing behaviors tend to covary with substance use (Elliott et al., 2012; Kodjo et al., 2004; Mulvey et al., 2010; Schubert et al., 2011). Last, we controlled for crucial milestones during young adulthood, which consisted of measures of education, marriage, and parenthood, because these factors tend to be associated with increased responsibilities, which may limit opportunities for victimization or substance use, reduce unstructured time with potential antisocial influences, or increase the significance, personal costs, and risks associated with these behaviors (Sampson & Laub, 1993; Siennick et al., 2014; Staff et al., 2010).

We hypothesized that adolescent victimization would be associated with age-35 substance use symptoms but that the effects would be reduced when controlling for young adult victimization and confounding variables.

Method

U.S. national panel data were drawn from Monitoring the Future (MTF), an ongoing study of substance use among adolescents and adults (Miech et al., 2019; Schulenberg et al., 2019). Project staff members have administered surveys in classrooms to approximately 16,000 American high school seniors (modal age = 18 years) each year since 1975. The average student response rate is 82.5% (range: 77%–86%), with nearly all nonresponse due to school absence. Approximately 2,450 individuals are randomly selected from each senior-year cohort for biennial follow-ups via mailed questionnaires. Drug users are oversampled for follow-up, and the data are weighted to adjust for the differential probability of selection (and for attrition, discussed later). Detailed information on MTF study procedures can be found elsewhere (Bachman et al., 2015; Miech et al., 2019; Schulenberg et al., 2019).

Participants and procedures

The analytic sample contained cohorts of seniors who graduated in 1976–1998 and participated in the age-35 follow up survey in 1993–2015, resulting in 5,291 unweighted cases (2,296 men and 2,995 women) for analysis. Each senior year cohort is randomly divided with half surveyed 1 year and half surveyed 2 years after graduation (at modal ages 19 and 20) and then every 2 years thereafter to ages 29 or 30 (six biennial surveys). Analyses combine the halves into six measurement waves at modal ages 19/20, 21/22, 23/24, 25/26, 27/28, and 29/30. All participants were additionally surveyed around age 35. Thus, the data in the present study included a total of eight measurement occasions spanning the period from age 18 to age 35. The victimization items were included on one (of six) survey forms. The six surveys were distributed randomly at age 18 and maintained longitudinally. The age-35 retention rate was 51.4%, comparable with other large-scale epidemiological studies (Galea & Tracy, 2007), and likely a reflection of the difficulties associated with long-term studies of drug use (McCabe & West, 2016). Those who did and did not complete the age-35 follow up did not differ in terms of adolescent cannabis use, alcohol use, threatened physical assaults, or injurious physical assaults (Supplemental Table 1). To account for the possibility of differential attrition, age-35 attrition weights were calculated for the present study and used in all analyses (Supplemental Table 1). (Supplemental material appears as an online-only addendum to the article on the journal’s website.)

Measures

Adolescent threatened physical assaults (age 18).

Pastyear threats of physical assaults were measured at age 18 with two items (i.e., has someone threatened you with injury without/with a weapon, but not actually injured you). Participants reported the frequency with which each item occurred over the previous 12-month period using a 5-point response scale (0 = not at all; 1 = once; 2 = twice; 3 = three or four times; 4 = five or more times). The final threatened physical assault variable was the number of times that the respondent was threatened with or without a weapon (whichever was highest) and truncated at two because very few adolescents were threatened three or more times in the past year at age 18.

Adolescent injurious physical assaults (age 18).

Like threats, injurious physical assaults during the previous 12 months were measured at age 18 with two items (i.e., has someone injured you on purpose without/with a weapon). Participants reported the frequency with which each item occurred with the same 5-point response scale described previously (ranged from 0 = not at all to 4 = five or more times). Injurious physical assaults in adolescence was the number of times that the respondent was injured with/without a weapon (whichever was highest) in the past year and was truncated at two because very few participants were injured three or more times in the past year.

Early young adult victimization (age 19–24).

The four previously described victimization items were included on the three surveys at ages 19/20, 21/22, and 23/24 and used to measure early young adult victimization. Participants were asked how many times they were threatened with/without a weapon or injured with/without a weapon in the past year using the previously described 5-point response scale. A mean of all items from the three surveys was used to represent early young adult victimization.

Later young adult victimization (age 25–30).

The previously described four victimization items were also measured at the three surveys from age 25/26 to 29/30. A mean of all items was calculated to represent victimization during later young adulthood.

Alcohol and cannabis use symptoms (age 35).

Alcohol and cannabis symptoms over the past 5 years were assessed at age 35. Fifteen items were used to measure 8 of 11 symptoms of criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013; e.g., social problems, withdrawal) for alcohol use disorder and 8 of 11 symptoms of DSM-5 criteria for cannabis use disorder (Supplemental Table 2). Each item assessed the frequency with which alcohol or cannabis caused problems in certain domains over the past 5 years. Respondents rated each item using a scale that ranged from “none” to “a lot.” Symptoms that were experienced “a little” or more often were considered present (1 = a little/some/a lot; 0 = not present). For symptoms with more than one item, the symptom was considered present if any items were experienced “a little” or more often. The eight binary symptom scores were summed to obtain overall symptom counts for alcohol symptoms and cannabis symptoms. More details regarding the substance use symptoms scales are available elsewhere (McCabe et al., 2016, 2017; Merline et al., 2008; Patrick et al., 2011; Schulenberg et al., 2016) and in Supplemental Table 2.

Covariates.

Control variables were measured during adolescence and young adulthood. Adolescent (age 18) covariates included past-month alcohol use (0 = none; 1 = any use); past-year cannabis use (0 = none; 1 = any use); past-month cigarette use (0 = none; 1 = one or more); and past-year other (noncannabis) drug use (0 = none; 1 = one or more). We also included measures of participant externalizing behavior, including interpersonal aggression, theft, and property destruction/trespassing. Interpersonal aggression was a binary indicator (0 = none; 1 = one or more) of whether participant engaged in any of five aggressive items in the past 12 months (e.g., hurt someone badly enough to need a doctor; threatened someone with a weapon). Theft was a binary indicator (0 = none; 1 = one or more) of whether participant engaged in any of five theft-related items in the past 12 months (e.g., stole something worth more than $50; shoplifted). Property destruction/trespassing was a binary indicator (0 = none; 1= one or more) of whether participant engaged in any of five items in the past 12 months (e.g., unauthorized entry into house/building; arson).

Young adult (ages 19–30) covariates were education (0 = lower than associate’s degree; 1 = associate’s or higher), marital status (0 = never married; 1 = married between ages 19 and 30 and not divorced, married at some point between ages 19 and 30 but divorced), and whether participant had any children (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Sociodemographic controls were sex (male vs. female); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White; Black; Hispanic; other); whether the participant lived in a two-parent home at the age 18 survey (0 = two-parent home; 1 = single or no parent in household); highest education level of parents (college degree or higher; some college, but no degree; high school diploma or less); urbanicity of primary residence during adolescence (suburban, rural, urban); and historical trends (i.e., cohort year) in alcohol and cannabis use based on a prior analysis with these data (Jager et al., 2013). All covariates were centered on the grand mean.

Data analysis plan

Research aims were addressed with negative binomial regressions. For both substances, Model 1 examined the associations between adolescent victimization and age-35 substance use symptoms, controlling for adolescent substance use and sex only. Next, we added young adult victimization (Model 2), and then the remaining covariates (Model 3). In the fully adjusted models (Model 3), we also examined models wherein we regressed the two young adult victimization measures on the two adolescent victimization measures and used indirect effects analysis to look at the effect of adolescent victimization on age-35 substance use symptoms through young adult victimization (e.g., adolescent threats → early young adulthood victimization → age-35 alcohol use symptoms). Last, we examined whether any of the associations varied by sex by including product terms between victimization and sex in the fully adjusted models. In addition, we examined supplemental models that explored the potential temporal ordering of substance use and victimization. In these models, we examined whether adolescent substance use was predictive of any of the victimization measures.

To minimize the potential impact of the sampling design and/or missing data, all models included sampling weights that adjusted for the oversampling of drug users and differential attrition (Supplemental Table 1). To further reduce the impact of missing data, all models were estimated with full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (Arbuckle, 1996) and conducted in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012).

Results

Descriptive statistics

At age 18, about 33% of youth reported that they were threatened with physical violence at least once and about 17% were threatened two or more times in the past year. In addition, about 18% were physically injured and about 7% were physically injured two or more times in the past year. On average, participants had about 1.13 alcohol use symptoms (SD = 1.70, range: 0–8) and about 0.32 cannabis use symptoms (SD = 1.05, range: 0–8) at age 35. About 55% reported no age-35 alcohol use symptoms and about 87% reported no age-35 cannabis symptoms. See Supplemental Tables 3 and 4 for correlations among study variables.

Alcohol use symptoms

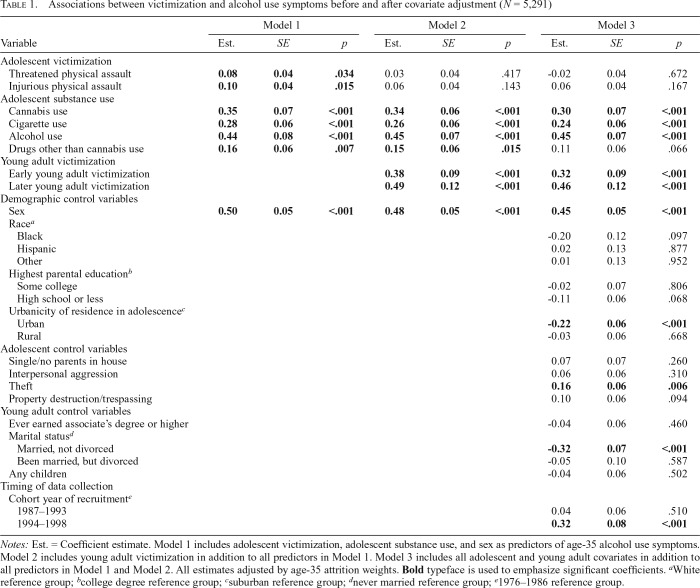

Threatened physical assaults and injurious physical assaults during adolescence were both associated with higher age-35 alcohol use symptoms, even after controlling for adolescent substance use (Table 1, Model 1). However, when young adult victimization was included, the effect of adolescent victimization became nonsignificant (Table 1, Model 2 and Model 3). Victimization during early young adulthood and during later young adulthood were both associated with higher age-35 alcohol use symptoms, before and after covariates were controlled for.

Table 1.

Associations between victimization and alcohol use symptoms before and after covariate adjustment (N = 5,291)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||

| Variable | Est. | SE | p | Est. | SE | p | Est. | SE | p |

| Adolescent victimization | |||||||||

| Threatened physical assault | 0.08 | 0.04 | .034 | 0.03 | 0.04 | .417 | -0.02 | 0.04 | .672 |

| Injurious physical assault | 0.10 | 0.04 | .015 | 0.06 | 0.04 | .143 | 0.06 | 0.04 | .167 |

| Adolescent substance use | |||||||||

| Cannabis use | 0.35 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.34 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.30 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Cigarette use | 0.28 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.24 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use | 0.44 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.45 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.45 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Drugs other than cannabis use | 0.16 | 0.06 | .007 | 0.15 | 0.06 | .015 | 0.11 | 0.06 | .066 |

| Young adult victimization | |||||||||

| Early young adult victimization | 0.38 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.32 | 0.09 | <.001 | |||

| Later young adult victimization | 0.49 | 0.12 | <.001 | 0.46 | 0.12 | <.001 | |||

| Demographic control variables | |||||||||

| Sex | 0.50 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.48 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.45 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| Racea | |||||||||

| Black | -0.20 | 0.12 | .097 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0.02 | 0.13 | .877 | ||||||

| Other | 0.01 | 0.13 | .952 | ||||||

| Highest parental educationb | |||||||||

| Some college | -0.02 | 0.07 | .806 | ||||||

| High school or less | -0.11 | 0.06 | .068 | ||||||

| Urbanicity of residence in adolescencec | |||||||||

| Urban | -0.22 | 0.06 | <.001 | ||||||

| Rural | -0.03 | 0.06 | .668 | ||||||

| Adolescent control variables | |||||||||

| Single/no parents in house | 0.07 | 0.07 | .260 | ||||||

| Interpersonal aggression | 0.06 | 0.06 | .310 | ||||||

| Theft | 0.16 | 0.06 | .006 | ||||||

| Property destruction/trespassing | 0.10 | 0.06 | .094 | ||||||

| Young adult control variables | |||||||||

| Ever earned associate’s degree or higher | -0.04 | 0.06 | .460 | ||||||

| Marital statusd | |||||||||

| Married, not divorced | -0.32 | 0.07 | <.001 | ||||||

| Been married, but divorced | -0.05 | 0.10 | .587 | ||||||

| Any children | -0.04 | 0.06 | .502 | ||||||

| Timing of data collection | |||||||||

| Cohort year of recruitmente | |||||||||

| 1987–1993 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .510 | ||||||

| 1994–1998 | 0.32 | 0.08 | <.001 | ||||||

Notes: Est. = Coefficient estimate. Model 1 includes adolescent victimization, adolescent substance use, and sex as predictors of age-35 alcohol use symptoms. Model 2 includes young adult victimization in addition to all predictors in Model 1. Model 3 includes all adolescent and young adult covariates in addition to all predictors in Model 1 and Model 2. All estimates adjusted by age-35 attrition weights. Bold typeface is used to emphasize significant coefficients.

White reference group;

college degree reference group;

suburban reference group;

never married reference group;

1976–1986 reference group.

Indirect effects.

Although the direct effects of adolescent victimization were not significant when controlling for young adult victimization, there were significant indirect effects from adolescent victimization to age-35 alcohol use symptoms via young adult victimization (e.g., adolescent injurious physical assaults → early young adult victimization → age-35 alcohol use symptoms; Supplemental Table 5). Specifically, adolescent victims of injurious assaults and adolescent victims of threatened physical assaults were more likely to be victimized during early and later young adulthood, and victimization during early and later young adulthood were both, in turn, associated with more alcohol use symptoms at age 35 (all p values for indirect effects < .05; Supplemental Table 5).

Sex interactions.

The interactions between the two young adult victimization variables and sex were significant (early young adult victimization interaction with sex: B = 0.43, p = .021; later young adult victimization interaction with sex: B = 0.56, p = .013), but the interactions with adolescent victimization were not significant. Probing of the significant interactions (i.e., rotating the sex reference group) suggested that the magnitudes of the associations between early young adulthood victimization and age-35 alcohol use symptoms and between later young adulthood victimization and age-35 alcohol use symptoms were larger for women than for men.

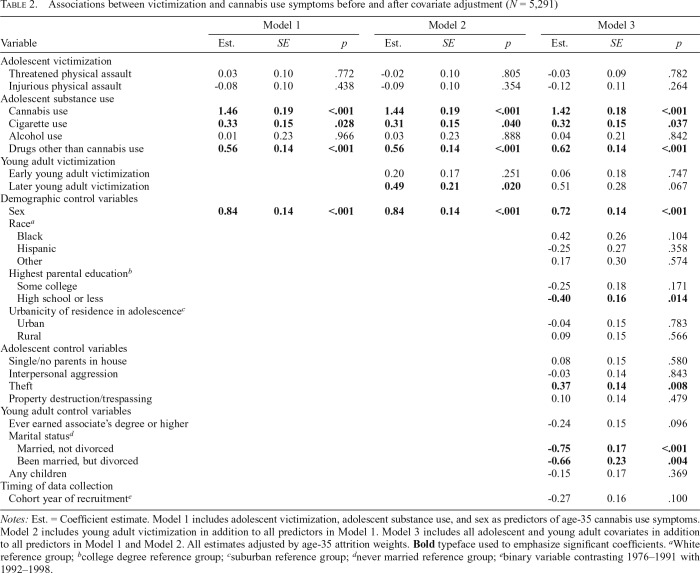

Cannabis use symptoms

None of the victimization items were significantly associated with age-35 cannabis use symptoms (Table 2) in the fully adjusted model. The only instance in which a victimization measure was significantly associated with cannabis symptoms was in Model 2 (i.e., later young adulthood; Table 2), but this effect became nonsignificant when the covariates were included. In addition, none of the interactions was significant.

Table 2.

Associations between victimization and cannabis use symptoms before and after covariate adjustment (N = 5,291)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||

| Variable | Est. | SE | p | Est. | SE | p | Est. | SE | p |

| Adolescent victimization | |||||||||

| Threatened physical assault | 0.03 | 0.10 | .772 | -0.02 | 0.10 | .805 | -0.03 | 0.09 | .782 |

| Injurious physical assault | -0.08 | 0.10 | .438 | -0.09 | 0.10 | .354 | -0.12 | 0.11 | .264 |

| Adolescent substance use | |||||||||

| Cannabis use | 1.46 | 0.19 | <.001 | 1.44 | 0.19 | <.001 | 1.42 | 0.18 | <.001 |

| Cigarette use | 0.33 | 0.15 | .028 | 0.31 | 0.15 | .040 | 0.32 | 0.15 | .037 |

| Alcohol use | 0.01 | 0.23 | .966 | 0.03 | 0.23 | .888 | 0.04 | 0.21 | .842 |

| Drugs other than cannabis use | 0.56 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.56 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.62 | 0.14 | <.001 |

| Young adult victimization | |||||||||

| Early young adult victimization | 0.20 | 0.17 | .251 | 0.06 | 0.18 | .747 | |||

| Later young adult victimization | 0.49 | 0.21 | .020 | 0.51 | 0.28 | .067 | |||

| Demographic control variables | |||||||||

| Sex | 0.84 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.84 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.72 | 0.14 | <.001 |

| Racea | |||||||||

| Black | 0.42 | 0.26 | .104 | ||||||

| Hispanic | -0.25 | 0.27 | .358 | ||||||

| Other | 0.17 | 0.30 | .574 | ||||||

| Highest parental educationb | |||||||||

| Some college | -0.25 | 0.18 | .171 | ||||||

| High school or less | -0.40 | 0.16 | .014 | ||||||

| Urbanicity of residence in adolescencec | |||||||||

| Urban | -0.04 | 0.15 | .783 | ||||||

| Rural | 0.09 | 0.15 | .566 | ||||||

| Adolescent control variables | |||||||||

| Single/no parents in house | 0.08 | 0.15 | .580 | ||||||

| Interpersonal aggression | -0.03 | 0.14 | .843 | ||||||

| Theft | 0.37 | 0.14 | .008 | ||||||

| Property destruction/trespassing | 0.10 | 0.14 | .479 | ||||||

| Young adult control variables | |||||||||

| Ever earned associate’s degree or higher | -0.24 | 0.15 | .096 | ||||||

| Marital statusd | |||||||||

| Married, not divorced | -0.75 | 0.17 | <.001 | ||||||

| Been married, but divorced | -0.66 | 0.23 | .004 | ||||||

| Any children | -0.15 | 0.17 | .369 | ||||||

| Timing of data collection | |||||||||

| Cohort year of recruitmente | -0.27 | 0.16 | .100 | ||||||

Notes: Est. = Coefficient estimate. Model 1 includes adolescent victimization, adolescent substance use, and sex as predictors of age-35 cannabis use symptoms. Model 2 includes young adult victimization in addition to all predictors in Model 1. Model 3 includes all adolescent and young adult covariates in addition to all predictors in Model 1 and Model 2. All estimates adjusted by age-35 attrition weights. Bold typeface used to emphasize significant coefficients.

White reference group;

college degree reference group;

suburban reference group;

never married reference group;

binary variable contrasting 1976–1991 with 1992–1998.

Supplemental analysis predicting victimization from adolescent substance use.

Adolescent cannabis use predicted threatened physical assaults in adolescence and early young adulthood victimization, but adolescent alcohol use was not predictive of any of the victimization outcomes (see Supplemental Table 6).

Discussion

This study examined the extent to which victimization during adolescence was associated with substance use symptoms in the mid-30s. Our results demonstrated that adolescent victims of injurious and threatened physical assaults were significantly more likely than nonvictimized peers to have alcohol use symptoms at age 35, almost 20 years later. Because the effects of adolescent victimization were significant even after controlling for adolescent substance use and alcohol use did not predict victimization in any of the supplemental analyses, our results support the hypothesis that victimization likely occurred before the alcohol use problems (and not vice versa).

However, the effects of adolescent victimization were completely accounted for by victimization during young adulthood. When victimization during young adulthood was included, the effects of adolescent victimization were reduced to nonsignificance, and victimization during the early and late 20s emerged as significant predictors of alcohol use symptoms in adulthood. Indeed, adolescent victimization was only indirectly related to age-35 alcohol use symptoms in the fully adjusted model (effects transmitted through young adulthood victimization). This suggests that any long-term association between adolescent victimization and later substance use problems is likely because victimization is a risk factor for future victimization. These findings are consistent with prior work that has shown that victimization at one time point tends to predict future victimization (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Fisher et al., 2015; Lauritsen & Quinet, 1995; Menard, 2000; Menard & Huizinga, 2001). These results could highlight the stability of an underlying proclivity or susceptibility for victimization (behavioral, circumstantial, lifestyle), or they could suggest that victims of violence begin selecting environments that eventually lead to more victimization, potentially motivated by a desire for retaliation (Lauritsen & Quinet, 1995; Menard, 2000; Menard & Huizinga, 2001). Future research should examine the mechanisms that underlie repeat victimization as this was outside the scope of the present study.

An important finding was that the effects of victimization during early and later young adulthood were significant predictors of later alcohol use symptoms, even after controlling for earlier alcohol use and several potential confounding variables. Because alcohol use peaks during the early 20s and is relatively more common in this age group (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002), alcohol may be an accessible and socially acceptable way to alleviate physical and emotional pain associated with physical victimization (Lin et al., 2011; Windle & Windle, 1996). In addition, some researchers have hypothesized that exposure to violence may lead to increased substance use because exposure to violence may lead to diminished growth or increasing deficits in self-regulation (e.g., impulse control) and other indices of psychosocial maturity (e.g., consideration of others, responsibility), which may increase substance use, but this hypothesis has not been supported empirically (Sullivan et al., 2007).

The pathways between victimization and later alcohol use symptoms were especially salient for women. One possible explanation is that women may be more likely than men to modulate negative affect with alcohol. In addition, given that women are more likely to be victims of domestic violence (Catalano, 2006), it is possible that women are more likely to be victimized by romantic partners whereas men may be more likely to be victimized by peers, community rivals, or strangers. In this case, it could be that violence perpetrated by a loved one has a particularly damaging effect on psychological functioning and behavior.

As shown in Table 2, the present study found that adolescent cannabis use was associated with greater cannabis symptoms in adulthood, but victimization was generally not associated with age-35 cannabis use symptoms. In addition, none of the sex interactions were significant, suggesting that the pattern of results was similar for women and men. As such, our results suggest that men and women both may be more likely to respond to negative life experiences, such as victimization, with alcohol than cannabis. The lack of significant effects of victimization on cannabis use symptoms is slightly inconsistent with a similar prior study (Menard et al., 2015). However, that study did not control for young adult victimization or several of the adolescent confounding variables that were included in the present study. The outcome variables were also measured differently in the two studies. We focused on symptoms of cannabis use disorder, whereas Menard et al. examined the prevalence of any cannabis use. Perhaps the risk factors for infrequent or casual cannabis use differ from the risk factors for symptoms of cannabis use disorder. Last, the base rate of age-35 cannabis use symptoms was low in the present study, which could have made it difficult to detect small effects.

Study strengths and limitations

Major strengths of the present study include the national multicohort sample, multiwave surveying of men and women from age 18 to 35, and the inclusion of several crucial explanatory variables. The present study also had limitations, some of which are common to large-scale prospective secondary analysis studies. First, given the MTF design, our findings may not represent high school dropouts or non-U.S. populations. In addition, there was differential attrition; however, this was mitigated to some extent by the inclusion of attrition weights. Furthermore, we do not know whether the context (or perpetrator) of the victimization was similar for men and women, or during adolescence and young adulthood, which means comparative statements about these categories should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, adolescent victimization referred to past-year incidents, whereas young adult victimization represented the average victimization during specific developmental periods. We speculated that substance use might be used to cope with negative affect or physical pain resulting from victimization, but future research should examine the mechanisms linking victimization to later substance use problems (see Margolin & Gordis, 2000). In addition, our outcome variables assessed substance use symptoms and were not clinical diagnoses. MTF only measured 8 of the 11 potential symptoms of substance use disorders, which means that our analysis may have underestimated symptom counts. It is also important to emphasize that substance use symptoms were measured over a 5-year period and were not necessarily present in the same year. Furthermore, we examined sex as a potential moderator, but future research should examine other moderators that identify the individuals for whom the associations reported here might be magnified (e.g., early substance use problems, history of childhood victimization or abuse, internalizing/comorbid mental health problems, and genetic predisposition; Fagan et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2011). Moreover, future studies should control for early substance use problems as we were only able to include measures of adolescent substance use. Controlling for early substance use problems would allow a stronger test of the directionality of the association. In addition, we only examined injurious and threatened physical assaults because other types of victimization were not measured in MTF (e.g., sexual assault, emotional abuse, verbal aggression, physical assaults that may not have resulted in injuries). Future research should include additional categories of victimization, as victims of one type of victimization are often the victim of other types (Finkelhor et al., 2007, 2009b; Fisher et al., 2015), and polyvictimization during adolescence is a robust risk factor for mental health and other behavioral and adjustment problems (Finkelhor et al., 2007, 2009a; Turner et al., 2017). Indeed, it is possible that the victims of threatened and injurious physical assaults in the present study were victims of other types of (unmeasured) victimization, which makes it unclear whether observed associations were directly related to the specific types of victimization examined in the present study.

Conclusion

Adolescent victims of injurious or threatened physical assaults are significantly more likely to develop alcohol problems by their mid-30s than nonvictimized peers, but these associations are completely accounted for by victimization during young adulthood. Indeed, adolescent victimization is predictive of adult alcohol use symptoms because victims of violence in adolescence are at risk for subsequent victimization during young adulthood, and this, in turn, places individuals at risk for alcohol problems in adulthood. Interventions in young adulthood that address victimization may ultimately reduce symptoms of alcohol use disorder in adulthood. Nonetheless, threatened and injurious physical assaults in adolescence and young adulthood are predictive of future alcohol use symptoms and could be useful components of prognostic instruments.

Footnotes

John Schulenberg acknowledges that the development of this research was supported by Grants R01DA001411 (to Richard Miech) and R01DA016575 (to John Schulenberg) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse/National Institutes of Health.The National Institute on DrugAbuse/National Institutes of Health had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–88. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:319–361. doi:10.1177/0022427801038004001. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R., White H. R. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology. 1992;30:475–500. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01113.x. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. L. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides G. A., Schumacker R. E., editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Atav S., Spencer G. A. Health risk behaviors among adolescents attending rural, suburban, and urban schools: A comparative study. Family & Community Health. 2002;25:53–64. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200207000-00007. doi:10.1097/00003727-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman J. G., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Schulenberg J. E., Miech R. A. The Monitoring the Future project after four decades: Design and procedures (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 82) Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2015. Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Begle A. M., Hanson R. F., Danielson C. K., McCart M. R., Ruggiero K. J., Amstadter A. B. Kilpatrick D. G. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S. J. Imaging brain development: The adolescent brain. NeuroImage. 2012;61:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.080. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. M. Intimate partner violence in the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donnermeyer J. F., Scheer S. D. An analysis of substance use among adolescents from smaller places. Journal of Rural Health. 2001;17:105–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2001.tb00266.x. doi:j.1748-0361.2001.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. S., Huizinga D., Menard S. Multiple problem youth: Delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan A. A., Wright E. M., Pinchevsky G. M. Exposure to violence, substance use, and neighborhood context. Social Science Research. 2015;49:314–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.08.015. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck R. S., Siegal H. A., Wang J., Carlson R. G. Differences in drug use among rural and suburban high school students in Ohio. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:567–577. doi: 10.3109/10826089909037231. doi:10.3109/10826089909037231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R. K., Turner H. A. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R. K., Turner H. A. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009a;33:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R. K., Turner H. A., Hamby S. L. Measuring poly-victimization using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1297–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Turner H., Ormrod R., Hamby S. L. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009b;124:1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher H. L., Caspi A., Moffitt T. E., Wertz J., Gray R., Newbury J., Odgers C. L. Measuring adolescents’ exposure to victimization: The environmental risk (E-Risk) longitudinal twin study. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:1399–1416. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000838. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A. H., Edleson J. L. Young children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Towards a developmental risk and resilience framework for research and intervention. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:151–163. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9065-3. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R. Z., Volkow N. D. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: Neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12:652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. doi:10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke K. A., Ruggiero K. J., Fitzgerald M. M., Zinzow H. M., Saunders B. E., Resnick H. S., Kilpatrick D. G. A longitudinal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:633–647. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.633. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J., Schulenberg J. E., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G. Historical variation in drug use trajectories across the transition to adulthood: The trend toward lower intercepts and steeper, ascending slopes. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:527–543. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001228. doi:10.1017/S0954579412001228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings W. G., Piquero A. R., Reingle J. M. On the overlap between victimization and offending: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:16–26. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. O., Mink M. D., Harun N., Moore C. G., Martin A. B., Bennett K. J. Violence and drug use in rural teens: National prevalence estimates from the 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of School Health. 2008;78:554–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00343.x. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., Prescott C. A., Myers J., Neale M. C. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Acierno R., Saunders B., Resnick H. S., Best C. L., Schnurr P. P. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingery P. M., Pruitt B. E., Hurley R. S. Violence and illegal drug use among adolescents: Evidence from the U.S. National Adolescent Student Health Survey. International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27:1445–1464. doi: 10.3109/10826089209047362. doi:10.3109/10826089209047362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodjo C. M., Auinger P., Ryan S. A. Prevalence of, and factors associated with, adolescent physical fighting while under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:346.e11–346.e16. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G. F., Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen J. L., Quinet K. F. D. Repeat victimization among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1995;11:143–166. doi:10.1007/BF02221121. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner R. M., Steinberg L. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. H., Cochran J. K., Mieczkowski T. Direct and vicarious violent victimization and juvenile delinquency: An application of general strain theory. Sociological Inquiry. 2011;81:195–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682x.2011.00368.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2011.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madruga C. S., Laranjeira R., Caetano R., Ribeiro W., Zaleski M., Pinsky I., Ferri C. P. Early life exposure to violence and substance misuse in adulthood—The first Brazilian national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.011. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G., Gordis E. B. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S. C., Ellickson P. L., McCaffrey D. F. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early to late adolescence: A comparison of rural and urban youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:430–440. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., West B. T. Selective nonresponse bias in population-based survey estimates of drug use behaviors in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;51:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1122-2. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Veliz P., Boyd C. J., Schulenberg J. E. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription sedatives and anxiolytics: Adolescents’ use and substance use disorder symptoms in adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;65:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Veliz P., Schulenberg J. E. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder symptoms at age 35: A national longitudinal study. Pain. 2016;157:2173–2178. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000624. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S. The “normality” of repeat victimization from adolescence through early adulthood. Justice Quarterly. 2000;17:543–574. doi:10.1080/07418820000094661. [Google Scholar]

- Menard S., Covey H. C., Franzese R. J. Adolescent exposure to violence and adult illicit drug use. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;42:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.006. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S., Huizinga D. Repeat victimization in a high-risk neighborhood sample of adolescents. Youth & Society. 2001;32:447–472. doi:10.1177/0044118X01032004003. [Google Scholar]

- Merline A., Jager J., Schulenberg J. E. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: Stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103(Supplement 1):84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R. A., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E., Patrick M. E. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S., Windle M. Initiation of alcohol use in early adolescence: Links with exposure to community violence across time. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:779–781. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey E. P., Schubert C. A., Chassin L. Substance use and delinquent behavior among serious adolescent offenders. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2010. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/59b3/415d6d081d90a8a9950af63cf41bd9a0cad9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Mplus user’s guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. Comparing rural and urban drug use and violence in the Pennsylvania Youth Study. Harrisburg, PA: Center for Rural Pennsylvania; 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.rural.palegislature.us. [Google Scholar]

- Mykota D. B., Laye A. Violence exposure and victimization among rural adolescents. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2015;30:136–154. doi:10.1177/0829573515576122. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel T. R., Overpeck M. D., Haynie D. L., Ruan W. J., Scheidt P. C. Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:348–353. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.348. doi:10.1001/archpedi.157.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Schulenberg J. E., O’Malley P. M., Johnston L. D., Bachman J. G. Adolescents’ reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinchevsky G. M., Fagan A. A., Wright E. M. Victimization experiences and adolescent substance use: Does the type and degree of victimization matter? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29:299–319. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505150. doi:10.1177/0886260513505150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R. J., Laub J. H. Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C. A., Mulvey E. P., Glasheen C. Influence of mental health and substance use problems and criminogenic risk on outcomes in serious juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.006. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Miech R. A., Patrick M. E. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-60. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Maggs J. L. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Patrick M. E., Kloska D. D., Maslowsky J., Maggs J. L., O’Malley P. M. Substance use disorder in early midlife: A national prospective study on health and well-being correlates and long-term predictors. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2016;9(Supplement 1):41–57. doi: 10.4137/SART.S31437. doi:10.4137/Sart.S31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siennick S. E., Staff J., Osgood D. W., Schulenberg J. E., Bachman J. G., VanEseltine M. Partnership transitions and antisocial behavior in young adulthood: A with-person, multi-cohort analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2014;51:735–758. doi: 10.1177/0022427814529977. doi:10.1177/0022427814529977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson T. L., Miller W. R. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems. A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:27–77. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00088-x. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J., Schulenberg J. E., Maslowsky J., Bachman J. G., O’Malley P. M., Maggs J. L., Johnston L. D. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:917–32. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. N., Farrell A. D., Kliewer W., Vulin-Reynolds M., Valois R. F. Exposure to violence in early adolescence: The impact of self-restraint, witnessing violence, and victimization on aggression and drug use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:296–323. doi:10.1177/0272431607302008. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. N., Kung E. M., Farrell A. D. Relation between witnessing violence and drug use initiation among rural adolescents: parental monitoring and family support as protective factors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:488–498. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_6. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. W., Kliewer W. Violence exposure and early adolescent alcohol use: An exploratory study of family risk and protective factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:201–215. doi:10.1007/s10826-005-9017-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp-Taylor S., Haviland A., D’Amico E. J. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M. P., Sims L., Kingree J. B., Windle M. Longitudinal associations between problem alcohol use and violent victimization in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman J. L., Langton L. Criminal victimization, 2014. 2015. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Turner H. A., Shattuck A., Finkelhor D., Hamby S. Effects of poly-victimization on adolescent social support, self-concept, and psychological distress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017;32:755–780. doi: 10.1177/0886260515586376. doi:10.1177/0886260515586376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeiren R., Schwab-Stone M., Deboutte D., Leckman P. E., Ruchkin V. Violence exposure and substance use in adolescents: Findings from three countries. Pediatrics. 2003;111:535–540. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.535. doi:10.1542/peds.111.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M., Windle R. C. Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: Associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:551–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.551. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E. M., Fagan A. A., Pinchevsky G. M. The effects of exposure to violence and victimization across life domains on adolescent substance use. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow H. M., Ruggiero K. J., Hanson R. F., Smith D. W., Saunders B. E., Kilpatrick D. G. Witnessed community and parental violence in relation to substance use and delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:525–533. doi: 10.1002/jts.20469. doi:10.1002/jts.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]