Dear Editor,

Since the appearance of human pathogenic members of the Coronaviridae family, which have not only mild, but also severe and fatal infection courses, these coronaviruses have become the focus of public interest. SARS-CoV-1 was identified as the pathogen during the SARS pandemic 2002–03 originated in China (Cherry and Krogstad, 2004). MERS-CoV persists in the Middle East region since 2012 (Corman et al., 2019) and SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Possible animal reservoirs have been discussed since the first appearance of SARS. These include various candidates such as horseshoe bat species (Rhinolophus spec.), raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), masked palm civets (Paguma larvata) or livestock (Luk et al., 2019, Gong and Bao, 2018). However, since more than 10,000 masked palm civets have been culled based on preliminary research (Cook and Karesh, 2012), care must be taken in the future, especially for species that are more vulnerable than palm civets like critical endangered Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) (Han, 2020).

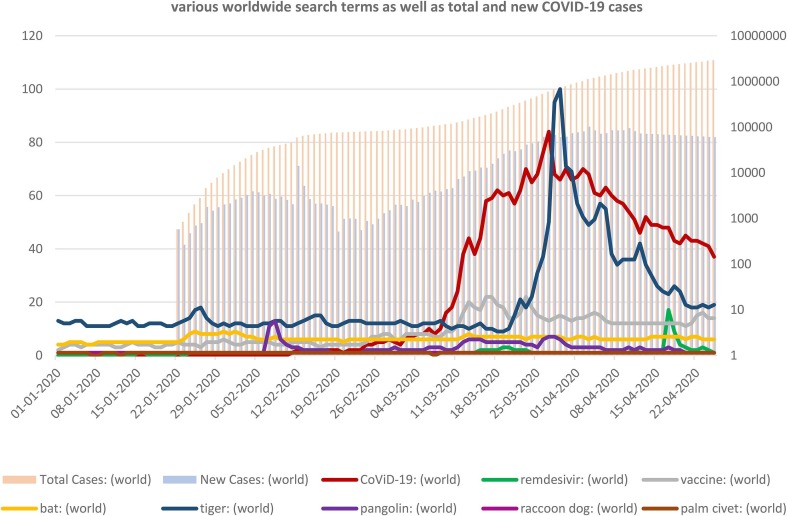

Since individual reports of a transmission of the new SARS-CoV-2 to pets and even zoo lions (Panthera leo) and tigers (P. tigris) in the Bronx Zoo were reported (Gollakner and Capua, 2020), corresponding peaks were revealed in search queries by Google Trends, in particular for the unusual transmission to lions and tigers (Fig. 1 ). For the Pearson correlation coefficient, a high correlation between the search terms “CoViD-19” and “tiger” (r = 0.669, p < 0.05) was found for the period from 1st January 2020 to 24th April 2020. In the same setting, the search terms for animal reservoirs that are being discussed (e.g. “bat”, “palm civet”, “racoon dog”, “pangolin”) have shown different results. Interest in bats remained relatively high and rose slightly at the end of January. However, the search queries for “pangolin” peaked in early February and also between mid and late March 2020. The search terms “palm civet” and “raccoon dog” returned only minor values in the selected setting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Display of Google Trends data for various worldwide search terms including total and new COVID-19 cases. Normalized search data were obtained from Google Trends according to Springer et al., 2020 (100 – high interest; 0 – no or insufficient interest data) for the period from 1st January to 24th April 2020. COVID-19 case data were obtained from Worldometers (worldometers, 2020) (accessed: 28th April 2020).

For the search term “palm civet” a low Pearson correlation coefficient was found (r = 0.148; p < 0.05). The search term “pangolin” revealed a medium correlation (r = 0.431, p < 0.05) also the search term “bat” (r = 0.300; p < 0.05). Furthermore, the search term “raccoon dog” revealed no correlation according to the search term “CoViD-19”.

In a recently published paper, Parry looks at the animal welfare and possible panic fear of being infected by pets (Parry, 2020). However, this potential fear is not reflected in Google searches for domestic cats or dogs. No significant data were found for search terms “domestic cat” and “domestic dog” (data not shown).

In contrast, there is clearly a need for information among the population regarding possible COVID-19 therapy options and medication. This can be clearly demonstrated for the publicly discussed drug remdesivir as well as the possibilities of vaccination (Li and De Clercq, 2020) by using Google Trends (Fig. 1). For the Pearson correlation coefficient a high correlation between the search term “CoViD-19” and the search term “vaccine” (r = 0.903, p < 0.05) was found. For “remdesivir” a medium Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.300, p < 0.05) was found.

As suggested elsewhere (Springer et al., 2020), Google Trends can only represent the interests of the population, but cannot clearly distinguish between fear or concern and pure interest. Likewise, certain terms that are widely used in the mass media seem to generate interest peaks.

Our data support that the main interest of the population is currently rather in the medical therapeutic direction and, apart from anecdotal individual reports (e.g. Bronx Zoo cats), there is less interest in possible virus carriers or the animal origin and reservoir.

References

- Cherry J.D., Krogstad P. SARS: the first pandemic of the 21st century. Pediatr. Res. 2004;56(1):1–5. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000129184.87042.FC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R.A., Karesh W.B. Emerging diseases at the interface of people, domestic animals, and wildlife. Fowler's Zoo Wild Animal Med. 2012;136 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Lienau J., Witzenrath M. Coronaviren als Ursache respiratorischer Infektionen [Coronaviruses as the cause of respiratory infections] Internist. 2019;60:1136–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00108-019-00671-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollakner R., Capua I. Is COVID-19 the first pandemic that evolves into a panzootic? Veterinaria Italiana. 2020 doi: 10.12834/VetIt.2246.12523.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S.R., Bao L.L. The battle against SARS and MERS coronaviruses: reservoirs and animal models. Animal Models Experimental Med. 2018;1(2):125–133. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.Z., 2020. Pangolins Harbor SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li Guangdi, De Clercq Erik. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2020;19(3):149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk, H.K., Li, X., Fung, J., Lau, S.K., Woo, P.C., 2019. Molecular epidemiology, evolution and phylogeny of SARS coronavirus. In: Infection, Genetics and Evolution. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parry N.M. COVID-19 and pets: when pandemic meets panic. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S., Menzel L.M., Zieger M. Google Trends provides a tool to monitor population concerns and information needs during COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.073. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [accessed: 28th April, 2020].