Abstract

Purpose

To describe the multiplicity of ocular manifestations of COVID-19 patients, we report a case of pseudomembranous and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis related with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in a patient of intensive care unit (ICU).

Observations

A 63-year-old male was admitted in intensive care unit (ICU), seven days after the beginning of an influenza-like symptoms, to manage an acute respiratory syndrome related with SARS-CoV-2. Chest scan showed interstitial pneumonia with “crazy paving” patterns. At day 19, ocular examination at the patient's bed described petechias and tarsal hemorrhages, mucous filaments and tarsal pseudomembranous. Conjunctival scrapings and swabs did not identify any bacteria or virus. To our knowledge, we described the first case of pseudomembranous conjunctivitis in a COVID-19 patient.

Conclusion and importance

Considering that SARS-CoV-2 is present in tears and conjunctival secretions, external ocular infections could be factors of infectious spreading. Physicians should be aware of late (>2 weeks) ocular complications in COVID-19 patients to prevent sequelae.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Pandemic, Conjunctivitis, Intensive care unit, External ocular infections

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a viral pneumonia epidemic named coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was initially described in Wuhan, China and rapidly spread around the world to become the most severe pandemic since Spanish Influenza.1 Because of phylogenetic analyses, the virus was later named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Despite unprecedented containment (more than half of world population), hundreds of thousands patients were infected among whom some developed severe respiratory symptoms requiring assisted ventilation and intensive care unit resources. The primary mode of transmission seem to be direct or indirect contact of mucous membrane with Pflügge droplets.2 Considering that the virus is present in tears and conjunctival secretions, external ocular infections could be factors of infectious spreading.3 There are few reports on the association of SARS-CoV-2 with ocular manifestations. In a Chinese case series, Wu et al. described nearly 30% of ocular symptoms in COVID-19 patients, including conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, or secretions.4 To describe the multiplicity of ocular manifestations of COVID-19, we report a case of pseudomembranous and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis related with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in a patient of intensive care unit (ICU).

1.1. Case report

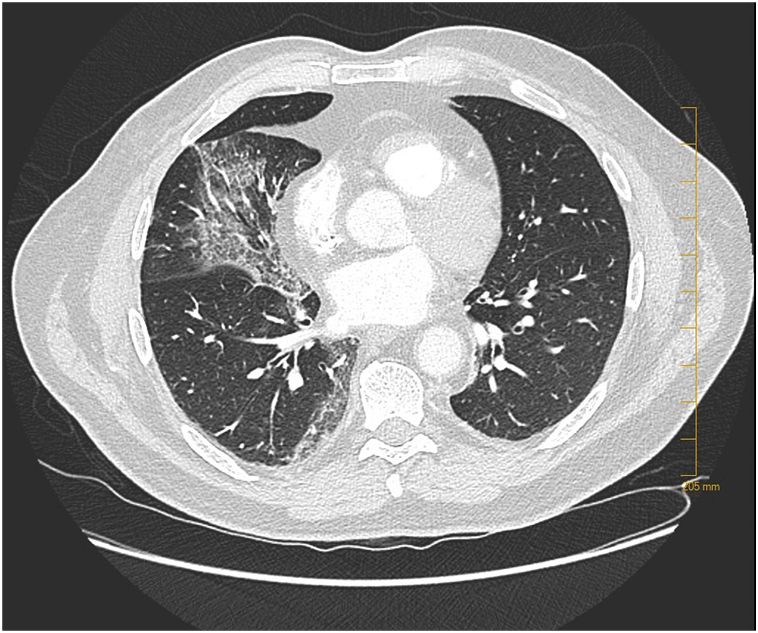

A 63-year-old male was hospitalized and diagnosed COVID-19 two days (day 2) after the beginning of an influenza-like symptoms including cough, myalgia, nausea and headache. His medical history was prostatic neoplasia treated by surgery, active smoking (half a pack of cigarettes a day), and obstructive sleep apnea. At day 4, he was transferred to the infectious disease department of the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand because of his dyspnea requiring 1 L/min of nasal oxygen. He received systemic Plaquenil and Azithromycin. At day 7, he was admitted in ICU to manage an acute respiratory syndrome, requiring an invasive ventilation (6 L/min). Chest scanner showed interstitial pneumonia with “crazy paving” patterns (Fig. 1). Daily, analyses of bronchial secretions identified SARS-CoV-2 by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). During the two first weeks of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there were no ocular complaints. At day 17, the first ocular manifestations occurred with conjunctival hyperemia and clear secretions, evoking a viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctival scrapings and swabs did not identify any bacterial (such as Chlamydia, Streptococcus or Staphylococcus) or viral etiology (such as Herpes virus or adenovirus) by direct microscopic examination and culture. The conjunctivitis was treated with eyelid hygiene, eyewash with physiologic serum and artificial tears. At day 19, the clinical signs were exacerbated with follicles, petechias, tarsal hemorrhages, and chemosis (Fig. 2). We identified thin yellowish-white translucid membranes on the tarsal conjunctiva of lower lids that could be easily peeled off without bleeding that we identified as pseudomembranous. The eyelids were irritated by numerous sticky secretions accumulating around the eyelashes. With a fluorescein eyedrop and blue light examination, we described mucous filaments, tarsal pseudomembranous and superficial punctuate keratitis. Because of its intubation, slit lamp and other evaluations of anterior segment complications (such as uveitis or intraocular hypertension) were not performed. The examination of the posterior segment (fundus examination) was completed at patient's bed with the Schepens ophthalmoscope, and did not identify any vitreous inflammation or retinal abnormalities. At day 20, repetition of conjunctival scrapings and swabs did not identify SARS-CoV-2 by PCR in conjunctival secretions and tears. Azithromycin eyedrop was introduced twice a day for 3 days, with low doses of dexamethasone and daily debridement of pseudomembranous to avoid conjunctival fibrosis and retraction. From day 21 to day 26, the ocular symptoms and conjunctivitis decreased, without corneal complications. At the time of writing, the patient is always in intensive care unit.

Fig. 1.

Chest scan of the COVID-19 patient hospitalized in intensive care unit, showing interstitial pneumonia with “crazy paving” patterns.

Fig. 2.

Hemorrhagic conjunctivitis with pseudomembranous related to SARS-Cov-2 (ocular examination at the patient's bed because of assisted ventilation). Right eye (A) and left eye (B).

2. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is well-known to cause life-threatening respiratory failure, but symptoms in other organs should not be ignored because representing alternative modes of transmission and putative others complications. Here, we describe the first published case of pseudomembranous conjunctivitis in a COVID-19 patient hospitalized in ICU. It seems to be salient to characterize the different ocular manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 to identify typical ocular disease due to coronavirus, and to prevent other source of contagion. In this case, the ocular examination had to be performed at patient's bed because of assisted ventilation and respiratory depression. The first ocular symptoms were developed two weeks after influenza-like symptoms. As recently published, most benign ocular complaints in COVID-19 patients occur around two weeks after the first symptoms, and involve conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, or secretions.4 Conjunctival swabs were negative in our case, which is consistent with literature reporting only 5% of patients with positive sampling.4 Others types of coronavirus are well-known to affect several species of animals with ocular manifestations as conjunctivitis, pyogranulomatous anterior uveitis, choroiditis with retinal detachment and retinal vasculitis.5 In 2004, SARS-CoV RNA was identified in tears of children with conjunctivitis symptoms.6 To explain the presence of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions, proposed theories include direct inoculation of SARS-CoV from infected droplets, the migration by the nasolacrimal duct or hematogenous infection of the lacrimal gland.7 Ocular symptoms can be the first complaints if the contamination takes place on eye mucous membranes.4 ICU physicians should be aware of ocular complications in severe COVID-19 patients to prevent sequelae.

3. Conclusion

We described the first case of pseudomembranous and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis related with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in a patient of intensive care unit (ICU). Ocular manifestations started lately in the natural evolution of COVID-19, with pseudomembranous appearing 19 days after the beginning of symptoms (an 11 days after admission into ICU). Considering that SARS-CoV-2 is present in tears and conjunctival secretions, external ocular infections could be factors of infectious spreading. However, conjunctival swabs seem to be often negative, complexifying the diagnosis. Physicians should be aware of late (>2 weeks) ocular complications in COVID-19 patients to prevent sequelae and to identify all clinical characteristics of SARS-CoV-2.

Patient consent

Consent to publish this case report was not obtained. The report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for Authorship.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this work declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Morens D.M., Daszak P., Taubenberger J.K. Escaping pandora's box — another novel coronavirus. N Engl J Med. February 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002106. NEJMp.2002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris J.S.M., Yuen K.Y., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Stöhr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(25):2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia J., Tong J., Liu M., Shen Y., Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. J Med Virol. March 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725. jmv.25725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu P., Duan F., Luo C. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in hubei province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. March 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty M.J. Ocular manifestations of feline infectious peritonitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971;159(4):417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Hoek L., Pyrc K., Jebbink M.F. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10(4):368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seah I., Agrawal R. Can the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affect the eyes? A review of coronaviruses and ocular implications in humans and animals. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(3):391–395. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1738501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]