Abstract

Background:

There is increasing evidence that depressive symptoms are associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. In current study, we aimed to investigate the effect of depressive symptoms on incident Alzheimer disease and all-cause dementia in a community sample of older adults.

Methods:

Participants were 1219 older adults from the Einstein Aging Study, a longitudinal cohort study of community-dwelling older adults in Bronx County, New York. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, 15-item) was used as a measure of depressive symptoms. The primary outcome was incident dementia diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, criteria. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the risk of incident dementia as a function of GDS score for the whole population and also for 2 different time intervals, <3 years and ≥3 years after baseline assessment.

Results:

Among participants, 132 individuals developed dementia over an average 4.5 years (standard deviation [SD] = 3.5) of follow-up. Participants had an average age of 78.3 (SD = 5.4) at baseline, and 62% were women. Among all participants, after controlling for demographic variables and medical comorbidities, a 1-point increase in GDS was associated with higher incidence of dementia (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.11, P = .007). After up to 3 years of follow-up, depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with dementia incidence (HR = 1.09; P = .070). However, after more than 3 years, GDS score was a significant predictor of incident dementia (HR = 1.13, P = .028).

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that depressive symptoms are associated with an increased risk of incident dementia in older adults.

Keywords: depression, incident dementia, Alzheimer disease, older adults, remediable risk factor

Introduction

The prevalence of Alzheimer disease (AD) and dementia is increasing as the population ages,1 imposing significant burden on patients, caregivers, and society.2 Identifying risk factors and protective factors for dementia is an essential first step toward the development of effective preventive interventions.3 Risk factors are either immutable (eg, age, gender, and ethnicity) or potentially modifiable. Many studies have suggested mood disorders and specially depression as potential remediable risk factors for dementia.4

Both clinical diagnoses of depression and subclinical depressive symptoms are very common in older adults5 and are associated with reduced health-related quality of life, increased medical costs,6 and cognitive decline.7 In addition to high rate of co-occurrence of depression with dementia,8 they share similar risk factors (stress, chronic pain, vascular disease, and so on)9 and similar regional changes in brain structure such as hippocampal atrophy10 and volume loss in inferior parietal and medial temporal lobes.11 Over the past 2 decades, several studies have linked late-life depression to the development of cognitive impairment and dementia.12–17 Some studies have failed to replicate these findings, potentially due to differences in the population of study, lack of power, or using different methods for measuring depressive symptoms.18,19 Many of these studies used clinical diagnosis of depression or a cutoff for depression scales, a valid approach for assessing major depression as a risk factor.18,19 However, only a few studies have examined the wider spectrum of depressive symptoms that including subclinical depression might also be of significance for the development of dementia.20,21

Studies of depression in elderly patients and dementia risk have been conflicting; most support an association, yet the nature of this association remains unclear22; depression could be a risk factor for dementia or a manifestation of subclinical dementia. Previously, our group has investigated the effect of severity of baseline depressive symptoms on risk of incident amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), showing that mild depressive symptoms in men and moderate/severe symptoms in women might be predictive of future aMCI in older adults.23 Most studies suggest an association between depression and cognitive decline,17 but the directionality of this association remains uncertain. Considering the long preclinical phase of dementia, it is conceivable that subclinical dementia causes depressive symptoms (ie, the reverse causality hypothesis). Although determining causality (or reverse causality) using data from cohorts is difficult, different approaches and statistical methods have been suggested to investigate causality using longitudinal data.24 One way to address this issue is to study the association of depression and dementia over a long follow-up time and then explore the association over short-term versus long-term follow-up period. Under the hypothesis that depression is a risk factor for dementia, we would expect to see an association between depression and incident dementia both in short-term and long-term follow-up periods, with a stronger association in long-term follow-up (ie, higher hazard ratio [HR]). Conversely, under the reverse causality hypothesis, one would expect to see a stronger association between depression and incident dementia in short-term follow-up.

The Einstein Aging Study (EAS), with more than 17 years of prospective data on depressive symptoms and cognitive function in a community-based sample of older adults, provides an opportunity to examine the role of depressive symptoms as risk factor for development of dementia. Although many studies have suggested depression is a risk factor for AD and dementia, it is not clear weather depressive symptoms (or subclinical depression) should be considered as risk factor for AD or dementia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to primarily explore the effect of depressive symptoms on the risk of incident all-cause dementia and AD and also to assess the different effects of short-term and long-term follow-up periods.

Methods

Study Population

The EAS is a community-based longitudinal study of cognitive aging and dementia located in Bronx, New York. The EAS is a longitudinal study of community-dwelling individuals aged 70 years and older residing in the Bronx, New York, initiated in 1993. Einstein Aging Study is a racially and ethnically diverse urban county. Participants were recruited initially using Health Care Financing Administration/Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (HCFA/CMS) rosters of Medicare-eligible persons aged 70 years and older. Medicaid/Medicare lists provide an extremely useful sampling frame for the target population. According to the CMS in the United States, these lists include 97% of community-residing individuals older than 65 years. Since 2004, New York City Board of Elections registered voter lists for the Bronx were used due to changes in policies for release of HCFA/CMS rosters.25 We estimate that the voter lists provide a sampling frame that includes over 90% of community-residing individuals older than 65 years using US Census data as a reference. The samples recruited using either strategy were similar with respect to age at baseline, sex, and education. Eligibility criteria for being enrolled in EAS study are age of 70 years or older, English speaking, and being nondemented at initial study visit. Comparison with US Census data indicates that the cohort is representative of the Bronx County community with respect to sex and educational level. Participants undergo annual assessments including clinical evaluations, a neuropsychological battery, psychosocial measures, medical histories, demographics, standardized assessments of activities of daily living, and self- and informant reports of memory and cognitive complaints. Study details are described elsewhere.25

This analysis includes data from participants enrolled between August 1994 and May 2016 with additional inclusion criteria including completion the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and having at least 1 subsequent annual follow-up.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at study entry. Study protocols were approved by the Einstein institutional review board.

Clinical Information and Measurement of Risk Factors

Trained research assistants used structured questionnaires to obtain demographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and years of education) as well as medical history at each annual visit. Using baseline medical history, we calculated a medical comorbidity index score26 (ranging from 0 to 9) from dichotomous self-report (present vs absent) of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, Parkinson disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as previously described.26 All participants also completed a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment that included the Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration (BIMC) test (a test of global cognitive function).27

The 15-item GDS was used to evaluate the presence of depressive symptoms.28 The GDS scores range from 0 to 15, and a cutoff of 6 or greater is used in many studies to determine clinically significant depression.29 Validity and reliability of GDS in cognitively normal and MCI groups has been established in prior studies.30,31

Dementia Diagnosis

Dementia was diagnosed according to standardized criteria at the time of study from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, and required impairment in memory plus at least 1 additional cognitive domain, accompanied by evidence of decline from a previous level of functioning.31 A licensed neuropsychologist used normative data to determine whether impairment existed in any of the 5 cognitive domains.32 A physician independently interviewed and examined each participant, completed a Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and documented a clinical impression of whether dementia was present.33–35 Final diagnostic determination was made at consensus case conferences attended by the neuropsychologist and a board-certified neurologist. Diagnosis of AD was made in individuals with dementia who met clinical criteria for probable or possible disease established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association.32

Statistical Methods

We assessed GDS as a continuous variable. The effect of baseline GDS on the risk of dementia incidence was evaluated using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, and estimated HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. The time to event was defined as the time from the baseline visit to the visit at which dementia was first diagnosed or to the date of last follow-up. We ran 2 different sets of models: (1) basic model, which included age at enrollment, sex, race, educational level, and chronic medical comorbidity as covariates and (2) advanced models, which included all covariates from basic model plus BIMC. The BIMC was added as a covariate to models to account for possible effect of baseline cognitive function on the report of depressive symptoms.

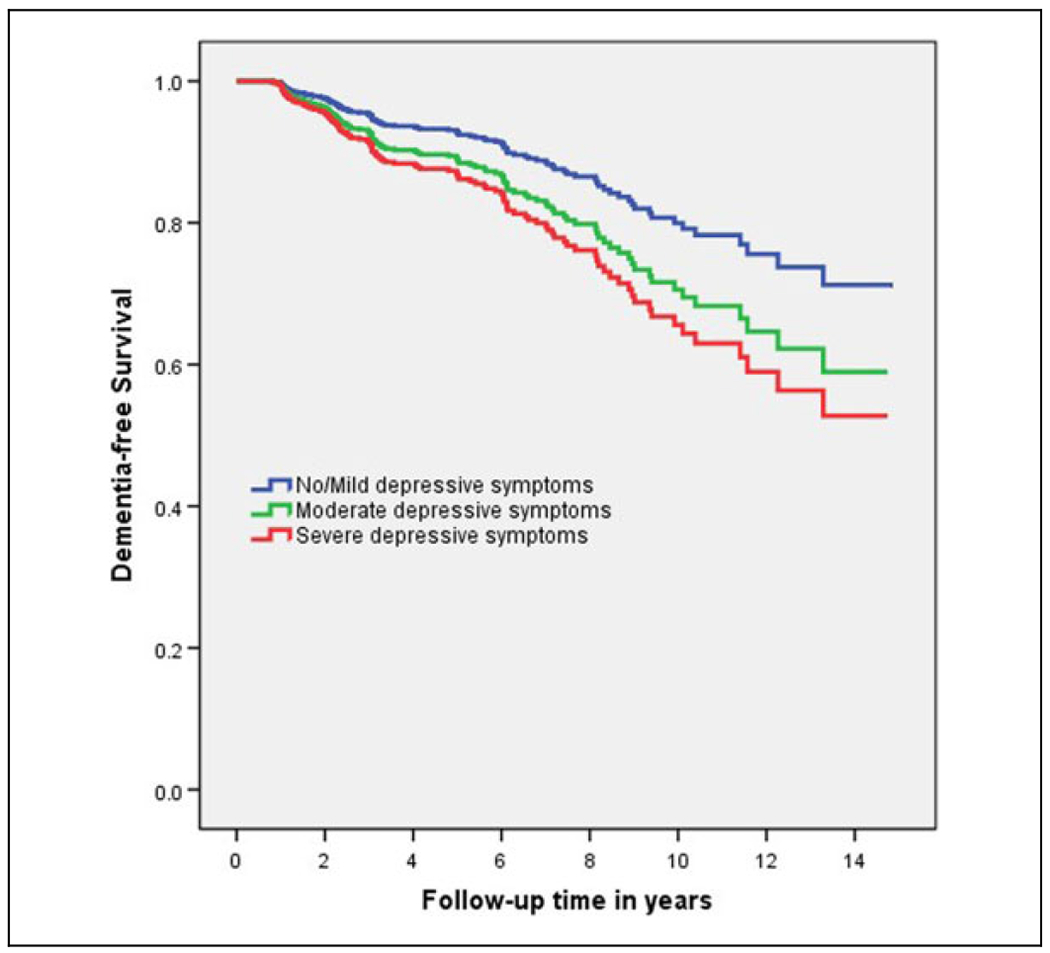

Initially, we examined the effect of baseline GDS on incident dementia. An analogous model was used to examine the effect of GDS on incident AD. Additionally, in a sensitivity analysis, participants were divided into 2 groups based on length of follow-up (<3 years vs ≥3 years), and Cox proportional hazard models were repeated for each group. Finally, in another sensitivity analysis, models were repeated while excluding participants who had clinical diagnosis of depression at baseline (based on self-reports). The proportional hazard assumptions for all models were adequately met according to methods based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals.33 For illustrative purposes, participants were categorized into 3 groups with no/mild (GDS = 0, 1, or 2), moderate (GDS = 3, 4, or 5), and severe (GDS ≥6) depressive symptoms, and Kaplan-Meier survival curve for dementia is presented based on this categorization.23 All other statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Demographics and Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics stratified by individuals who at final assessment developed dementia or remained dementia free. The study included 1219 individuals, 62% of which were females. Mean age at baseline was 78.3 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.3). Participants were followed for a maximum of 17.2 years (mean 4.4, SD = 3.1), during which 132 individuals developed the new onset of dementia (for more information about incidence rate of dementia in EAS population, please see Derby et al34). Applying the accepted cutoff of 6 or greater for GDS, 9.6% (N = 118) of the study population had clinically relevant depressive symptoms at baseline. Our statistic models assessed GDS as a continuous variable with values ranging from 0 to 15, although we present results graphically trichotomizing GDS as noted below. The group that developed dementia were on average older (t = 5.4, P < .001) but did not differ in sex, race, and education.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Variables in the Entire Sample and by Dementia Status at Follow-Up.

| Total Sample, N = 1219 | Remained Free of Dementia, n = 1087 | Developed Dementia, n = 132 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 756 (62) | 670 (61.6) | 86 (65.2) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 801 (65.7) | 715 (65.8) | 86 (65.2) |

| Age, years (SD) | 78.3 (5.3) | 78.1 (5.3) | 80.7 (5.4) |

| Education, years, mean (SD) | 13.8 (3.5) | 13.9 (3.5) | 13.5 (3.7) |

| GDS, mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.30 (2.3) | 2.5 (2.3) |

| BIMC, mean (SD) | 2.38 (2.3) | 2.14 (2.1) | 4.27 (2.9) |

| Follow-up time, years, mean (SD) | 4.5 (3.5) | 4.6 (3.5) | 4.2 (3.2) |

Abbreviations: BIMC, blessed information-memory-concentration; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

Depressive Symptoms and Incidence of All-Cause Dementia and AD

In basic models, Cox proportional hazard models showed that for each point of increase in depressive symptoms scale, the risk of all-cause dementia increased (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03-1.19; P = .007) after adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and medical comorbidity (Table 2). In advanced models, while accounting for the effect of baseline cognitive function (BIMC score added to the model as covariate), the effect of baseline depressive symptoms on incident dementia remained significant (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; P = .041). Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the risk of dementia for those with no/mild depressive symptoms (GDS = 0, 1, or 2), moderate depressive symptoms (GDS = 3, 4, or 5), or severe depressive symptoms (GDS ≥6) is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Hazard Ra2tios for Incident All-Cause Dementia and Incident Alzheimer Dementia Using Baseline Level of GDS as Predictor.

| Models for All-Cause Dementia |

Models for AD |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age at baseline | 1.13 | 1.10-1.17 | <.001 | 1.12 | 1.08-1.15 | <.001 | 1.15 | 1.11-1.19 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.09-1.17 | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 0.99 | 0.68-1.44 | .988 | 1.04 | 0.71-1.52 | .829 | 0.91 | 0.60-1.37 | .655 | 0.97 | 0.64-1.47 | .875 |

| Race, white | 0.80 | 0.55-1.17 | .257 | 1.30 | 0.87-1.93 | .190 | 0.87 | 0.57-1.33 | .527 | 1.37 | 0.88-2.11 | .162 |

| Education | 0.98 | 0.93-1.03 | .433 | 1.05 | 1.01-1.11 | .027 | 0.97 | 0.92-1.03 | .358 | 1.05 | 0.99-1.10 | .074 |

| Medical comorbidity | 0.92 | 0.78-1.08 | .317 | 0.97 | 0.82-1.14 | .699 | 0.84 | 0.70-1.01 | .059 | 0.90 | 0.75-1.08 | .258 |

| GDS | 1.11 | 1.03-1.19 | .007 | 1.08 | 1.01-1.16 | .041 | 1.13 | 1.05-1.22 | .001 | 1.11 | 1.03-1.20 | .009 |

| BIMC | 1.46 | 1.37-1.56 | <.001 | 1.46 | 1.36-1.57 | <.001 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BIMC, blessed information memory concentration; CI, confidence interval; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for 3 levels of depressive symptoms (blue line: no/mild depressive symptoms, red line: moderate depressive symptoms, green line: severe depressive symptoms).

Of the 132 individuals with incident dementia, 111 met criteria for probable or possible AD. Repeating Cox proportional hazard models for prediction of AD as the outcome yielded similar results (Table 2). In both basic and advanced models, depressive symptoms were a significant predictor of dementia due to AD (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.20; P = .001, and HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05-1.22; P = .009, respectively).

Subsequently, in order to further evaluate the possibility of reverse causality, that is, persons with preclinical cognitive impairment may be more vulnerable to depression, we conducted sensitivity analyses by stratifying outcomes based on time to dementia diagnosis (“short-term” or <3 years vs “long-term” or ≥3 years). The results indicated that the effect of baseline depressive symptoms on incident dementia remained significant only in the group with incidence more than 3 years after enrollment (Table 3). Although results for dementia onset over <3 years was not statistically significance.

Table 3.

Risk of Development Incident All-Cause Dementia Based on Level of Depressive Symptoms at Baseline.

| Short-Term Follow-Upa |

Model 2: Long-Term Follow-Upb |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia cases/total, N |

66/1219 |

66/696 |

||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age at baseline | 1.13 | 1.08-1.18 | <.001 | 1.09 | 1.05-1.13 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.08-1.20 | <.001 | 1.14 | 1.08-1.20 | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 1.06 | 0.63-1.78 | .816 | 1.14 | 0.68-1.9 | .619 | 0.96 | 0.56-1.65 | .897 | 0.97 | 0.56-1.70 | .928 |

| Race, white | 1.01 | 0.58-1.75 | .966 | 1.74 | 0.97-3.01 | .061 | 0.63 | 0.37-1.07 | .092 | 0.88 | 0.50-1.55 | .669 |

| Education | 0.96 | 0.90-1.03 | .336 | 1.08 | 1.01-1.15 | .025 | 0.99 | 0.92-1.07 | .839 | 1.04 | 0.96-1.11 | .240 |

| Medical comorbidity | 0.92 | 0.73-1.15 | .464 | 0.98 | 0.78-1.22 | .874 | 0.89 | 0.71-1.13 | .369 | 0.90 | 0.716-1.15 | .422 |

| GDS | 1.09 | 0.99-1.20 | .070 | 1.06 | 0.961-1.17 | .234 | 1.13 | 1.01-1.26 | .028 | 1.11 | 1.01-1.22 | .043 |

| BIMC | 1.60 | 1.47-1.75 | <.001 | 1.30 | 1.15-1.46 | <.001 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BIMC, blessed information memory concentration; CI, confidence interval; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HR, hazard ratio.

Model 1: Including patients with a diagnosis of dementia before 3 years of follow-up.

Model 2: Including patients with a diagnosis of dementia after 3 years of follow-up.

Finally, to evaluate whether active treatment for a diagnosis of clinical depression and use of medications for treatment (based on self-reports) had any effect on the outcomes, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding participants who had a clinical diagnosis of depression at baseline visit (N = 125). In these models, depressive symptoms remained a significant predictor of incident dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22; P = .003).

Discussion

This cohort study demonstrates a significant association between higher depressive symptoms and increased incidence of both all-cause dementia and AD. Although the hazard ratio of 1.10 may seem modest, this reflects increased risk for every point on the GDS, a scale whose values range from 0 to 15. The risk of dementia associated with depressive symptoms was stronger after 3 years of follow-up, although there was a nonsignificant trend during the first 3 years of follow-up.

Many of the previous studies that have examined the association between depression and dementia in older adults indicated that depression at baseline predicts incident dementia,12–17 and some studies have not found these associations.18,19 Discrepancies among studies may be partially related to the methods that were used to diagnose clinical depression or the use of cutoff scores for diagnosis of depression. Such methods might underestimate the effect of mild or moderate depressive symptoms in patients who do not meet clinical criteria for depression. Overall, our results are in line with other studies that examine the wider spectrum of depressive symptoms.20,21

Different explanations for the observed association between depression and incident dementia have been suggested.9 One possible explanation could be the effect of confounding measures like treatment for clinical depression. In a sensitivity analysis, we found that excluding participants who had severe symptoms consistent with a clinical diagnosis of depression or were treated for it during the follow-up time, depressive symptoms remained a significant risk for incident dementia. In addition, risk factors common to depression and dementia, such as cerebrovascular disease, could explain this association.35 Finally, depression could be a manifestation of preclinical dementia in persons free of full-blown dementia. We investigated this hypothesis with 2 different methods. First, BIMC, a test of mental status known to be sensitive to cognitive performance prior to the diagnosis of dementia, was added to the models to account for baseline cognitive function.36 If depression is a manifestation of preclinical dementia, and BIMC is sensitive to subtle cognitive decline, adjustment for BIMC should attenuate the effect of depression on incident dementia. The effect of depressive symptoms on incident dementia remained significant in models accounting for the BIMC. Second, under the reverse causality hypothesis, we would expect to see a higher HR when baseline depressive symptoms were measured close to the time of dementia diagnosis. However, our results indicated that the association between depressive symptoms and incident dementia was slightly higher in the long-term follow-up group. These results support the hypothesis that depression is a risk factor for incident dementia and not a manifestation of preclinical dementia. Another plausible explanation based on our findings is that depressive symptoms may have a true causal effect on incident dementia through hippocampal damage mediated by the influence of depression on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.37,38 This finding is the opposite of the prediction, which would be made under the reverse causality hypothesis. It should be noted that the observed differences were minimal, and there was significant overlap between upper and lower limits of HR in the models, and therefore the results must be interpreted cautiously. Although our study could not directly address the exact mechanisms linking depression and dementia, the observation that depressive symptom is a significant predictor of incident dementia in the long-term follow-up group is in favor of this hypothesis.

Similar to other observational data, this study cannot directly address the crucial mechanistic question of whether depression is a symptom of cognitive impairment (ie, if depression and dementia are different symptoms of the same underlying process) or whether depression adds independently to the risk of incident cognitive impairment. One potential mechanism is the growing evidence that inflammatory mechanisms are important in the neurotoxicity of AD39and in mood disorders.40 Future studies may address these mechanistic pathways by examining the association of depressive symptoms and biomarkers in prodromal dementia states.

Strengths of this study include using a large community-based sample of older adults spanning over 17.2 years. However, there are also some limitations that warrant mention. The GDS elicits self-report retrospective reports of depressive symptoms over a 1-month period and might not be a true representation of depressive symptoms over a longer period of time. One solution to this issue in future studies is to prospectively collect information about daily depressive symptoms over the course of weeks or months. Furthermore, the residual confounding due to unknown or unmeasured confounders such as physical activity, diet, or genetic factors that could predispose to both depressive symptoms and cognitive decline and effect of medications that are not intended for treatment of depression but affect mood and depressive symptoms (eg, β-blockers) were not assessed in this study. It is also important to note that this study focuses on the presence and effect of depressive symptoms on incident dementia in adults aged older than 70 years; however, the presence of early-life and midlife depressive symptoms can also affect cognitive function in later life. Future research is needed to isolate the specific psychological and biological elements of depression that drive the relationship between depression and cognitive decline to better understand the underlying mechanistic pathways and identify intervention strategies.

In conclusion, our study of community-based older adults demonstrates that depressive symptoms are an independent predictor of dementia. Since the presence of clinical depression or depressive symptoms are potentially remediable risk factors for dementia, the mechanisms that link depression to cognitive decline merit further exploration. Depression has huge potential for being targeted with a variety of interventions such as mindfulness, psychotherapy, and pharmacologic treatments, which could, in turn, decrease incident dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Einstein Aging Study staff for assistance with recruitment, and clinical and neuropsychological assessments. In addition, we appreciate all of the study participants who generously gave their time in support of this research.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NIA 2 P01 AG03949, NIA 1R01AG039409-01, NIA R03 AG045474; the Leonard and Sylvia Marx Foundation; and the Czap Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2015; 11(3):332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JH, Lin KP, Chen YC. Risk factors for dementia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(10):754–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9): 819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005; 365(9475):1961–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unützer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorm AF. Is depression a risk factor for dementia or cognitive decline? Gerontology. 2000;46(4):219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enache D, Winblad B, Aarsland D. Depression in dementia: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(6):461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, et al. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezzati A, Zimmerman ME, Katz MJ, Lipton RB. Hippocampal correlates of depression in healthy elderly adults. Hippocampus. 2013;23(12):1137–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreescu C, Butters MA, Begley A, et al. Gray matter changes in late life depression—a structural MRI analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(11):2566–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen K, Lolk A, Kragh-Sørensen P, Petersen NE, Green A. Depression and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen R, Hu Z, Wei L, Qin X, McCracken C, Copeland JR. Severity of depression and risk for subsequent dementia: cohort studies in China and the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(5):373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richard E, Reitz C, Honig LH, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(3): 383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saczynski JS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Auerbach S, Wolf P, Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2010;75(1):35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker JT, Chang Y-F, Lopez OL, et al. Depressed mood is not a risk factor for incident dementia in a community-based cohort. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(8):653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson A, Korten A, Jacomb P, et al. The course of depression in the elderly: a longitudinal community-based study in Australia. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirza SS, de Bruijn RF, Direk N, et al. Depressive symptoms predict incident dementia during short-but not long-term follow-up period. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(5):S323–S329.e321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Xue QL, Carlson MC. Depressive symptoms predict incident cognitive impairment in cognitive healthy older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(6):323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundermann EE, Katz MJ, Lipton RB. Sex differences in the relationship between depressive symptoms and risk of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1): 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Illari PM, Russo F, Williamson J. Causality in the Sciences. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Hall CB, et al. Age and sex specific prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia in blacks and whites: a report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(4): 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders AE, Wang C, Katz M, et al. Association of a functional polymorphism in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene with memory decline and incidence of dementia. Jama. 2010;303(2):150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968; 114(512):797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter violence. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marc LG, Raue PJ, Bruce ML. Screening performance of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale in a diverse elderly home care population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(11):914–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debruyne H, Van Buggenhout M, Le Bastard N, et al. Is the Geriatric Depression Scale a reliable screening tool for depressive symptoms in elderly patients with cognitive impairment? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24(6):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994; 81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derby CA, Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Hall CB. Trends in dementia incidence in a birth cohort analysis of the Einstein Aging Study. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(11):1345–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexopoulos GS. Vascular disease, depression, and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(8):1178–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katzman R, Brown T, Thal LJ, et al. Comparison of rate of annual change of mental status score in four independent studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1988;24(3): 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacQueen GM, Campbell S, McEwen BS, et al. Course of illness, hippocampal function, and hippocampal volume in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(3): 1387–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8): 1516–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg PB. Clinical aspects of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(6):503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines and psychopathology: lessons from interferon-a. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(11): 819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]