Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this paper was to examine the context of injection drug use in Kabul, Afghanistan among injection drug users (IDUs) utilising and not utilising needle and syringe programmes (NSPs).

Methods:

Following identification of themes from eight focus group discussions, free-lists were used for further exploration with both NSP using (n=30) and non-NSP using (n=31) IDUs.

Results:

All participants were male, had been injecting for 5 years (mean), and most (95%) had been refugees in the past decade. Main reasons for sharing syringes were convenience and lack of availability and did not vary based on NSP use. Drug users perceived alienation from the community, evidenced by names used for drug users by the community which convey social stigma and moral judgment. Health risks were the principal stated risk associated with drug use, which was mentioned more frequently by NSP users. Harm reduction services available in Kabul are perceived to be insufficient for those in need of services, resulting in underutilisation. The limited scope and distribution of services was frequently cited both as an area for improvement among NSP using IDU or as a reason not to use existing programmes.

Conclusions:

While some positive differences emerged among NSP-using IDU, the current context indicates that both rapid scale-up and increased variety of services, particularly in the realm of addiction treatment, are urgently needed in this setting.

Keywords: Afghanistan, injection drug user, needle sharing, needle and syringe programme, freelist, rapid assessment

Introduction:

Injection drug use is likely relatively new to Afghanistan. However, the number of injection drug users (IDUs) is estimated to be growing, believed due in part to return of refugees from neighbouring countries where injecting practices may have been acquired and greater local availability of heroin (UNODC 2005, UNODC 2003, MacDonald & Mansfield 2001). In 2003, a UNODC report estimated that 470 IDU resided in Kabul and heroin injection was described as an emerging problem (UNODC 2003). In this report, key informants noted transition from heroin smoking to injection to avoid police detection. Though fear of police and other authorities predated the Taliban regime, these fears were heightened during Taliban rule, where corporal and potentially capital punishments were meted out to those violating the Muslim proscription against intoxicant use or an action, including cultivation, fostering use (UNODC 2003, Farrell & Thorne 2005). This UNODC report was among the first to mention sharing injecting equipment among IDUs in Kabul (UNODC 2003).

With many internally-displaced people, newly returned refugees, and political unrest in many areas of the country, Kabul’s population is constantly in flux, with possible resultant changes in local drug use context. In a 2005 Afghan national survey, Kabul had the greatest per capita density of problem drug users, including the greatest number of drug injectors (UNODC 2005). In 2005-2006, a seroprevalence study in Kabul reported measurable prevalence of HIV (3%), hepatitis C antibody (36.6%), and hepatitis B surface antigen (6.5%) among 464 IDU, which, with reports of increasing drug use, have stimulated interest and investment in harm reduction programming (UNODC 2005, Todd 2007). However, because this study was quantitative, no crucial details were provided on context of the risk environment, which are needed to inform culturally appropriate programmes.

In Kabul, there are currently four no-cost drug rehabilitation programmes; however, there are only 50 total beds available at any time with several month long waiting lists. At the time of writing, there were no opioid substitution therapy programmes and methadone and buprenorphine were not legal for importation. There are three needle and syringe programmes (NSPs), with all performing either primary or secondary exchange in the field. However, little information exists on perceived programme quality or suggested means of improvement from intended clientele.

Describing drug use can be challenging as detailed descriptive methods, such as in-depth interviews, may not be acceptable to populations fearful of authorities and unwilling to participate in time-consuming research activities, as has been reported among Afghan drug users (UNODC, 2003). Further, sizeable population shifts in Kabul and changes in the number of drug users in Afghanistan in the last four years have likely changed drug use context in Kabul (UNODC, 2005). However, accessing drug users for research activities continues to be challenging, particularly because drug use is extremely culturally unacceptable. Rapid assessment and response (RAR) studies employ multiple techniques for assimilating large amounts of information from diverse sources, with resultant recommendations for interventions for drug users (Stimson 2006). RAR activities may benefit from additional modalities for rapidly obtaining contextual information from IDUs, often the target audience of interventions informed by RAR.

Freelist methodology, an alternative approach to obtaining qualitative data, was developed to sample terms contained within a given category (e.g., cultural domain), without imposing investigator assumptions on respondents (Borgatti 1998, Borgatti 1999, Quinlan 2005). Participants create a list of items contained within a category with the interviewer repeating the list prompts until the respondent can think of no additional items. In general, 30 participants will fully elucidate a cultural domain (Weller 1988). This methodology allows for qualitative data collection while providing a means to rapidly analyse data and provide timely information. The accuracy and ease of collection of free-lists are ideal when the study population may be unable or unwilling to undergo an in-depth interview. Free-lists have been used in a variety of settings but to our knowledge have not been previously used to describe the context of injecting drug use. The purpose of this study was to describe the current context of injection drug use and available harm reduction programmes in Kabul and to compare the perceptions between those utilizing and not utilizing NSPs, using free-list methodology.

Methods:

Study activities were conducted in two phases, comprising focus group discussions and individual free-list interviews. All interviews, document translation, and data entry occurred in Kabul; approval from domestic and international institutional review boards was obtained prior to study initiation. Study personnel trained in human subjects research and interview techniques performed all activities.

Focus Groups

Eight focus group discussions were conducted in December 2006 to define main themes to be explored in the free-list statements. Two focus groups each of harm reduction workers (n=10 and 8), community and religious leaders (n=8 and 7), NSP-using IDU (n=7 and 3), and non-NSP using IDU (n=4 and 6) were conducted. Potential participants for harm reduction worker focus groups were recruited from programme staff, with one focus group containing managers and medical providers and the second containing outreach workers representing all Kabul programmes. In-depth interviews, which are excellent sources of contextual information, were not performed due to time and resource constraints.

Potential participants for IDU focus groups were recruited by outreach workers known to the IDU community. For non-NSP using IDU, one IDU member was recruited from known social networks at sites of group congregation. NSP-using IDU were recruited by outreach workers affiliated with the respective NSP programmes, with at least one IDU from each programme present for each of the focus groups.

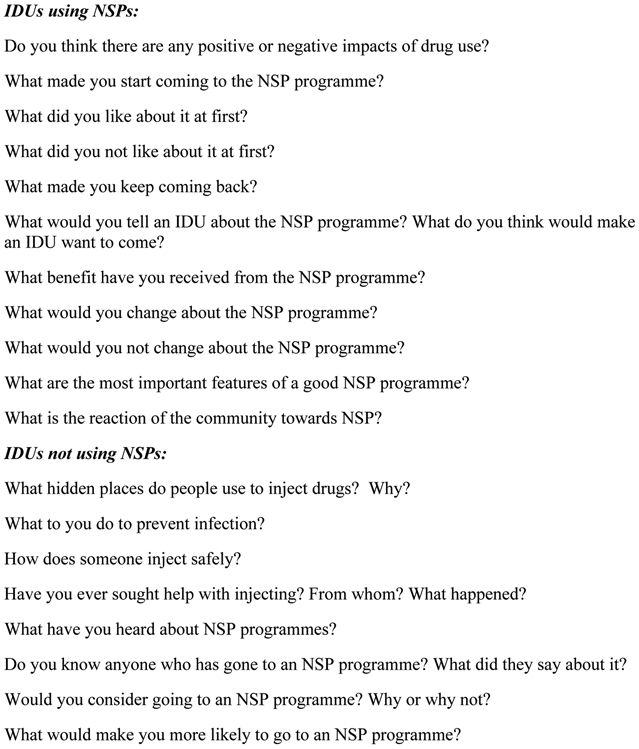

For all focus groups, consented participants were invited into a private room containing only the moderator (MRS) and a male session recorder. No female IDUs were recruited and there were no female representatives from harm reduction programmes. Topics discussed during the focus groups are listed in Figure 1. Written session transcripts were translated and reviewed by the moderator for accuracy. Focus groups discussions were coded by hand using a framework analysis approach and emergent themes were used to inform the free-list statements (Malterud 2001). No compensation was provided to focus group participants.

Figure 1.

Questions asked during the focus group discussions for harm reduction workers and community leaders, for injection drug users (IDUs) utilizing needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) and for IDUs not utilizing NSPs.

Individual Free-List Interviews

Free-list topics were developed based on focus group results, with the list statements translated and piloted for accuracy and assurance of listing of responses among 7 IDUs. Interview packets were then assembled with list generating statements arranged in variable order. Free-list interviews were conducted from February through April 2007. The intended sample size for each group was 30 participants, based on the number required to elucidate a cultural domain (Weller 1988). Four lists were asked of all participants and three non-NSP dependant lists were asked of a mixture of 30 to 31 NSP and non-NSP using IDU; lists not asked of all participants were those with greater similarity in pilot assessments and therefore less likely to generate new information.

Participants were recruited by outreach workers and introduced to the accompanying study representative; NSP-using participants were invited to either the harm reduction centre from which they obtained services or to the International Rescue Committee (IRC) office, based on participant preference. Non-NSP IDUs were invited to the IRC office. Potential participants were taken to a private room and informed consent obtained.

Following informed consent, participants were assigned a unique non-identifying code number and provided a hypothetical list statement on an unrelated topic (breakfast foods) with a sample list read as an example. Following this example, the list statement containing elements from Figure 1 was read and the participant created the list. The statement was repeated at the end of that list and, following completion of all statements, each statement was reviewed to determine if any additional items were to be added. For some lists, follow-up questions were asked after list completion for frequent mentions, such as specific values (e.g. money earned daily by begging) or unusual mentions (e.g. getting someone addicted as a means of revenge). At the end of the interview, a brief demographic and drug use behaviour screener (including questions about new needle usage and refugee history) was completed. Participants were provided with a meal and transportation.

Primary freelist analysis was conducted using the principles described by Borgatti (Borgatti 1998). The first part of analysis was the standardisation of language across lists. Freelists were initially analyzed using ANTHROPAC version 3.2 (Borgatti) to examine the frequencies of each item. Saliency was not examined due to bias introduced by randomising the order of the freelist questions. To accomplish this, each list item was coded in ATLAS-ti, version 5.2 (ATLAS-ti Center, Berlin, Germany) using a coding scheme that emerged from the list itself. Because each participant was asked exactly the same questions, these codes could then be aggregated and statistics produced on the frequency of each item. If an item was repeated in a list, it was removed from analysis. After all the items in a list were coded, these codes were grouped into themes and a theme name was assigned to capture the overall sense of the codes.

Because multiple lists were used in random order, overall list length was compared to the order in which the free-list question was asked to determine if the order in which the list question was asked impacted the number of items given.

Results:

Focus Groups

The focus group transcripts were used to generate freelist statements. These statements were tested in the target population, with 10 freelist questions selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for Each Freelist: Mean, Min-Max and Standard Deviation

| Question | N | Mean | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: List the reasons that people start injecting drugs. | 31 | 4.6 | 3 | 9 | 1.63 |

| B: List the main problems for drug users. | 60 | 6.2 | 3 | 11 | 1.90 |

| C: List all the risks of drug use. | 61 | 6.9 | 3 | 11 | 1.71 |

| E: List all the ways drug users get money. | 31 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 1.15 |

| F: List all of the reasons people change from smoking to injecting. | 30 | 4.6 | 2 | 8 | 1.52 |

| G: List all of the reasons people share needles. | 61 | 3.9 | 1 | 8 | 1.43 |

| I: List all the names people use when talking about drug users. | 61 | 5.1 | 3 | 9 | 1.48 |

| AA: List all the benefits of the needle exchange programme. | 31 | 3.3 | 1 | 7 | 1.60 |

| BB: List all the problems with the needle exchange programme. | 31 | 4.2 | 2 | 10 | 1.76 |

| CC: List all the ways you would improve the needle exchange programme. | 31 | 4.6 | 1 | 10 | 2.23 |

Free-list interviews

A total of 61 IDUs participated in the freelist phase. The non-NSP group comprised 30 IDUs and the NSP group comprised 31 IDUs currently using NSP services in Kabul.

Demographic and Drug Use Behaviour Questions

Study participants in these two groups did not differ significantly by demographic variables. The mean age was 31.7 years (IQR: 24-38). Participants reported injecting an average of 2.89 times per day (range: 0.5-7) with a mean of 4.98 years of injecting (IQR: 2-6) and 50.8% reporting using a new needle 50% of the time or more. Overall, 41% of participants were married and 8.2% reported being employed. Most participants reported having been a refugee in Iran (95%, n=53/58) or Pakistan (22%, n=13/58); 14 reported being refugees in multiple countries including Turkey (n=6), Iraq (n=1) and Dubai (n=1). The participants did significantly differ by reported daily use of new needles. Non NSP-users reported using a new needle 1.39 times of 2.86 mean daily injections while NSP-users reported daily new needle usage at 2.13 times of 2.93 mean daily injections (p = 0.004; OR 5.0 (CI: 1.67 – 14.93). When new needle usage was analysed by NSP utilisation status, more NSP users reported new needle use at least 50 % of the time as compared to NSP non-users (65% vs. 36%; OR=5.00, 95% CI: 1.67-14.93).

Content of Free-lists

Each free-list is presented with summary statistics and emergent themes. Items in parentheses indicate total number of responses. Numbers relating to each theme may not equal the total mentions as items only listed by a few respondents were omitted. Lists did not differ significantly between the NSP users and the NSP non-users except where indicated.

List all the names people use when talking about drug users (free-list I)

309 mentions were generated, of which 280 (90.6%) were elements of three themes that emerged: drug use, behaviour/appearance and moral judgment. Names in italics are the Dari words preceded by the accompanying English translation.

Drug Use (129 mentions; 41.7%):

The most common names used were related to drug use. Items included: heroin user (poderi) (85; 65.9%), addict (neshiee) (35; 27.1%), smoker (mohatad zawarakee dudi) (7; 5.4%), and alcoholic (2; 1.6%).

Behaviour/appearance (98 mentions; 31.7%):

Participants reported being called names in relation to behaviour or appearance of drug users. Items included: ‘crazy’ because “we use drugs and cannot control ourselves,” “because we have convulsions when using drugs” and “because we go place to place like a dog” (49; 50.0%), dirty (25; 25.5%) and beggar (malang) (24; 24.5%).

Moral Judgment (53 mentions; 54.1%):

Names reflecting moral condemnation or judgment include: thief (27; 50.9%), lazy and immoral person (loafar) (7; 13.2%), being isolated from society (qalandry) because “we are separated from our families and cannot go back” and “we do not think about the world” (6; 11.3%) and careless (charsi) (3; 5.7%). Other terms included “germs of society” (mikrobajamiaá) and “useless.”

List the reasons that people start injecting drugs (Free-list A)

142 mentions were generated, of which 127 (89.4%) were elements of four themes: physical effects, convenience/cost, mental/psychological problems and social pressures.

Physical Effects (64 mentions; 45.1% of total):

The main reason reported for initiation of injecting drugs is the physical effects of the drug. Items included opinions that injecting generated a stronger effect than other routes of administration (18; 28.1%), effects from injecting are felt faster (18; 28.1%), they “enjoy it” (10; 15.6%), injecting relieves pain (8; 12.5%), injecting increases sexual desire (5: 7.8%) and the effects of injecting last longer – up to 24 hours (4; 6.3%).

Convenience/Cost (38 mentions; 26.7%):

Items included opinions that injecting is convenient and can be done anywhere, even a bathroom (18; 47.4%) and the daily cost of injecting drugs was cheaper compared to smoking heroin which started at 100 Afghanis (U.S. $1=49 Afghanis (Afs)) and could be as high as 500 Afs as one develops tolerance, whereas injecting costs as little as 50 Afs per dose (18; 47.4%). The freedom and speed with which injection could be conducted was seen as a benefit to avoid police harassment.

Mental/psychological Problems (14 mentions; 9.9%):

These problems included depression (7; 50%) and a need to ‘ease the mind’ (5; 35.7%). One participant noted that “people inject drugs when experiencing severe anxiety and worry”.

Social Pressures (11 mentions; 7.7%):

These pressures include: peer pressure (9; 81.8%) or being ‘hooked’ by someone who was paid by an enemy (1; 9.1%).

List the main problems for drug users (free-list B).

378 mentions were generated, of which 366 (96.8%) were elements of three themes: problems of survival, problems with organisations and problems with family and community.

Problems of survival (204 mentions; 54.0%):

This theme covered the top four items: lack of shelter, especially at night (56; 26.0%), lack of clothing (47; 21.9%), lack of money (34; 15.8%) and lack of food (33; 15.3%). Also included were concerns about lack of shoes (20; 9.3%), and fear of death from exposure (4; 1.9%)

Problems with organisations (115 mentions; 30.4%):

The police were identified as the entity most likely to cause problems by the greatest number of participants. Reported troubles with police included taking money, needles, and syringes; giving beatings; and forcing them to clean the police station (32; 39.5%). Harm reduction programmes were criticised for lack of treatment including perceptions that large bribes and strong connections were necessary to enter drug treatment (30; 37.0%). Additionally, participants remarked on lack of employment (23; 27.2%), inability to wash because IDUs are not permitted in public bath houses (15; 18.5%), lack of available medical care including no services for overdose (5; 6.2%), and inability to access public transportation as drivers refuse IDUs on the grounds that IDUs are ‘dirty’ (5; 6.2%).

Problems with family and community (47 mentions; 12.4%):

Participants reported stigma from various sources, ranging from insults, body searches by community leaders who confiscated their drugs (26; 55.3%), and isolation from families, including banishment until the IDU is no longer using drugs (18; 38.3%).

List all the risks of drug use (free-list C)

418 mentions were generated, of which 411 (98.3%) were elements of two themes: health related risks and depression. NSP users were somewhat more likely to mention health-related risks of drug use (130 mentions; mean 4.2), compared to non-NSP users (105 mentions; mean: 3.5).

Health Related Risks (352 mentions; 84.2%):

Stated health related risks included: death (41; 11.6%), shortness of breath (31; 8.8%), heart problems (27; 7.7%), HIV/AIDS (23; 6.5%), liver problems (23; 6.5%), brain problems (21; 6.0%), infection (19; 5.4%), that drug use ‘dries the blood’ [a common phrase used to refer to anaemia] (18; 5.1%), skin damage caused by the needle (15; 4.3%), sexual problems (14; 4.0%), stomach problems (14; 4.0%), hepatitis (12; 3.4%), paralysis from needle damage (7; 2.0%), “dry bones” (7; 2.0%), “both black and white jaundice” (6; 1.7%), overdose (6; 1.7%), abscesses (5; 1.4%) and that IDUs have “a worm in the brain” (3; 0.9%).

Isolation and Depression (59 mentions; 14.1%):

Participants mentioned risks involving isolation from family (37; 62.7%), mental problems (16; 27.1%), stigma (4; 6.8%) and depression (3; 5.1%).

Notable single responses:

One participant stated he learned about HIV risk from needle sharing from a harm reduction centre in Iran and another participant mentioned learning this in Pakistan. One participant explained that “there is a danger of death when a needle hits a nerve” and another believed “there is a danger of overdose if the needle hits a blood vessel”.

List all the ways drug users get money (free-list E)

123 mentions were generated, of which 122 (99.2%) were elements of five themes: begging, stealing, working, selling items and sex work. One of the follow-up questions asked for an estimated amount earned from each method (though a conclusion cannot be made about which method is most common or most profitable).

Begging (37 mentions; 30.1%):

Participants reported obtaining between 30 and 200 Afs daily through begging. Items in this category included begging (31; 83.8%), borrowing from family members (4; 10.8%) and receiving charity (kharat and zakat) (1; 2.7%).

Stealing (31 mentions; 25.2%):

Participants reported obtaining 100 to 500 Afs daily through stealing. Items mentioned included stealing (27; 87.1%), pick-pocketing (2; 6.5%), mugging other IDUs (1; 3.2%) and stealing shoes outside a mosque (1; 3.2%).

Working (24; 19.5%):

Participants reported obtaining between 100 and 500 Afs daily through work. Items mentioned included daily labour (15; 62.5%), collecting garbage and steel for 100 Afs daily (5; 20.8%) and working for a drug dealer for 10% commission, usually on 1000 Afs of drugs sold (4; 16.7%).

Selling items (22 mentions; 17.9%):

Participants reported the selling of household items, including appliances, rugs, and food (15; 68.2%), and land (6; 27.3%). One participant reported selling a kidney in Iran and said “the money lasted only three months.”

Sex Work (8 mentions; 6.5%):

The male participants reported various forms of sex work to obtain money for drugs. Items mentioned included: homosexual activities, especially by “boys” who were reported to obtain 50-100 Afs per sex act (4; 50.0%), forcing their wives into sex work (2; 25.0%), female IDUs using sex work to obtain money (1; 12.5%) and the selling of a wife (1; 12.5%).

List all of the reasons people change from smoking to injecting (free-list F)

138 mentions were generated, of which 137 (99.3%) were elements of four themes: effect of injecting, convenience, social and mental.

Effect of Injecting (60 mentions; 43.5%):

Items include: injecting makes the drug take effect faster (18; 30.0%), tolerance to smoking develops over time (16; 26.7%), the effect of injecting is stronger (14; 23.3%), people enjoy injecting - “once someone enjoys the effects of injecting, he will never return to smoking” (6; 10.0%), and the effects of injecting last longer (3; 5.0%).

Convenience (45 mentions; 32.6%):

Convenience was another major reason given for why people switch from smoking to injecting (see the results for Free-list A for more detail). Items include: injecting is cheaper than smoking (21; 46.7%), injecting is more convenient (15; 33.3%) and a person can inject anywhere (9; 20.0%).

Social (21 mentions; 15.2%):

Items listed include: peer pressure, including how an IDU often asks a non-IDU friend for help injecting and eventually the friend just tries it (16; 76.2%), that IDUs get help from organisations (jackets, soap, shoes) and journalists pay for pictures of IDUs injecting where non-IDU do not receive these advantages (3; 14.3%), and injecting is a “good activity to do in a group”, described as ba hesabi para (literally sitting in a line, but in this context, injecting in a group)(1; 4.8%).

Mental (11 mentions; 8.0%):

Items listed include: depression (6; 54.5%), severe anxiety and worry (4; 36.4%), and the perception that “They (IDU) are unfortunate for a long time and the people say let’s leave them to die soon”(1; 9.0%).

List all of the reasons people share needles (free-list G)

239 mentions were generated, of which 229 (95.8%) were elements of five themes: convenience, availability, cost, awareness and social.

Convenience (80 mentions; 33.5%):

Items listed include: takes too long to find new needles because participants are “too busy finding drugs” (26; 32.5%), harm reduction services are not reliable “needles not supplied on time” (18; 22.5%), too busy looking for a safe place to inject (9; 11.3%), must travel too far to get new needles (8; 10.0%) and “too high” [intoxicated] to obtain new needles (8; 10.0%).

Lack of Availability (53 mentions; 22.2%):

Items include: pharmacies refuse to give and/or sell needles and syringes to IDUs (38; 71.7%) and that new needles are simply “not available” (15; 28.3%).

Cost (51 mentions; 21.3%):

Participants also reported that a lack of money and the high cost of needles were a reason that people shared (51; 100.0%). Reports of cost ranged from 10 to 40 Afs for a syringe (2 - 5 Afs) and one ampoule of Avil (pheniramine maleate; antihistamine used with for heroin to increase effect and act as diluent) (8 – 30 Afs).

Awareness (26 mentions; 10.9%):

Participants mentioned that a lack of awareness about the dangers of needle sharing as reasons for why people shared (26; 100.0%) Of these, 14 (45.1%) were NSP users and 8 (26.7%) were non-NSP users.

Social Pressures (19 mentions; 7.9%):

Items mentioned include: the practice of ba hesabi para (15; 78.9%) and that “sharing is normal” (3; 15.8%).

Only current NSP users (n=31) were read the following three statements. However, non-NSP users were asked why they do not utilize services.

List all the benefits of a needle exchange programme (free-list AA)

103 mentions were generated, of which 101 (98.1%) were elements of four themes: infection prevention, critique of service, counselling/information and injection supplies.

Only participants currently using an NSP were asked this question. The responses on the benefits of NSP produced four themes that accounted for 101 of 103 items (98.1%) emerged from this list.

Prevent Infection (62 mentions; 60.2%):

Responses included: prevent infection (16; 25.8%), prevent HIV/AIDS (13; 21.0%), treat/prevent abscesses (9; 14.5%) and prevent hepatitis (7; 11.3%).

Critique of Service (19 mentions; 18.4%):

Participants provided unsolicited critiques of the Kabul-based programmes, often informed by their first-hand experience with harm reduction programmes in Iran or Pakistan. Reponses included: services are not provided properly (12; 63.2%), and there is a need to provide shelter (2; 10.5%) and substitution therapy (2; 10.5%).

Counselling/Information (10 mentions; 9.7%):

Items listed include: counselling (6; 60.0%), information (2; 20.0%) and motivation to seek treatment (2; 20.0%).

Injection Supplies (10 mentions; 9.7%):

Provision of injection supplies were mentioned as a benefit of the harm reduction programmes.

List all the problems with the needle exchange programme (free-list BB)

130 mentions were generated, of which 129 (99.2%) were elements of three themes: scope of services, logistics/service provision and organisational problems.

Scope of Services (61 mentions; 46.9%):

Participants reported that the scope of services provided is insufficient to meet their needs. Items listed include: need for drug treatment (11; 18.0%), need for money (10; 16.4%), need for shelter at night (8; 13.1%), needing treatment for abscesses (8; 13.1%), need for food (4; 6.6%), and needing information about risks/health maintenance (3; 4.9%).

Logistics/Service Provision (53 mentions; 40.8%):

Many of the participants compared the programmes in Kabul unfavourably to those they experienced or heard about in Iran and Pakistan. Items mentioned in the list include: supplies not delivered on time and only once weekly (23 mentions; 43.4%), problems with transportation (6 mentions; 11.3%), bad rapport with the harm reductions workers (4; 7.5%), that harm reduction services are closed on Fridays and holidays (4; 7.5%), and the need for more needles/syringes to be distributed each time (2; 3.8%).

Organisational Problems (15 mentions; 11.5%):

Items mentioned include: pharmacies refuse to distribute needles/syringes (9; 60.0%) and police harass drug users coming to the service for needles (6; 40.0%).

Notable single responses included, “Harm reduction workers give empty promises of treatment,” and “In Afghanistan they are not doing the work that is needed (unlike other countries) and they are very weak - we should be given methadone as it may save us from risks.”

List all the ways you would improve the NSP (free-list CC)

143 mentions were generated for list A, of which 133 (93.0%) were elements of three themes: scope of services, logistics and partnering.

Scope of Services (80 mentions; 55.9%):

Participants emphasized the need to increase the scope of services offered by NSPs in Kabul. Items mentioned include the need for: abscess treatment (10; 12.5%), night shelter (9; 11.3%), food (7; 8.8%), increased awareness about risks among IDUs (7; 8.8%), clothes (7; 8.8%), substitution therapy (6; 7.5%), counselling (5; 6.3%), a place to wash (4; 5.0%), giving out more needles (4; 5.0%) and providing a means of transportation, since “drivers do not allow us to ride and if we walk, the police will harass us” (3; 3.8%).

Logistics (35 mentions; 24.5%):

Items mentioned include: more frequent delivery of supplies including “asking how many syringes we need” (23; 65.7%) and providing better/more locations (12; 34.3%). Locations suggested specific neighbourhoods “where the drug users are:”

Partnering with Other Organisations (18 mentions; 12.6%):

Items mentioned include: involving pharmacies by advising them to give supplies to IDUs (12; 66.7%) and involving police to prevent harassment and allow travel (6; 33.3%).

Effect of Free-list Order

Ten freelist statements were asked. Mean items per respondent varied from 3.3 to 6.9 over all lists (range: 1-11) (Table 1). To examine whether respondent fatigue decreased list length of free-lists asked later in the interview, item number was examined by order in which the freelist was asked. Freelists asked first in the interview (n=61) averaged 4.98 items per respondent while freelists asked seventh (n=31) averaged 4.66 items per respondent. No difference in freelist length emerged based on the order in which the freelists were asked (p=0.81) (Table 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first survey exclusively examining the context of injection drug use in Kabul, Afghanistan. Several themes were consistent with those voiced in the 2003 UNODC survey, particularly the names drug users are called (UNODC 2003). Some important changes were also noted, possibly reflecting either change in context over time or factors unique to IDU in Kabul.

Reasons for changing from smoking to injecting and for initiating injection drug use were similar, with the most frequent being the more powerful effect of injected drugs and relative convenience of injecting. The potency of injecting relative to smoking and the decreased cost associated with this process may lead to increased adoption of injecting if these beliefs are widely communicated by IDU to acquaintances who currently smoke. The 2003 Kabul study indicated that advertisement of the pleasurable effects of heroin in Iran resulted in injection use among some Afghan refugees (UNODC 2003). Similar enticements or pressure from social contacts have lead to adoption of injecting in other settings (Swift 1999, Bravo 2003). The economic realities associated with less drug needed each day with injecting may compel current smokers to change in this impoverished environment. These factors should be considered when implementing policy as preventing initiation of injecting is one means of harm reduction; this concept has been outlined in the 2005 policy document for prevention of HIV/AIDS and injecting drug use and needs to be emphasized as the official policy to groups planning to implement harm reduction (MoCN/ MoPH, 2005). This is particularly important as harm reduction programmes are seen by some IDU to provide better or more services to injectors and may unwittingly encourage initiation of injecting. Though few IDU remarked on this bias as a reason to start injecting, harm reduction service providers and the government bodies providing oversight must ensure that there is no bias towards injectors in services received.

Needle sharing, a commonly reported activity in prior Kabul assessments, is likely to persist based on the limited sources for obtaining free or low cost sterile needles (Todd 200, UNODC 2005). The reported limited availability of syringes and needles from pharmacies is particularly concerning, as pharmacies were reported main source for new syringes for more than 90% of IDU in 2005 to 2006 (Todd 2007). The reported increase in price of syringes (reported as 1 Afghani in 2005) and refusal of pharmacies to sell syringes to drug users due to concern for violation of Ministry of Public Health stipulations may drive an increase in syringe sharing. Additionally, current NSP programmes were criticized for not providing both a sufficient quantity of supplies or supplies in a timely fashion. The perceived urgent need most IDU have for injecting equipment may make it impossible to meet these expectations, with resultant continuation of sharing practices. However, these reports clearly indicate that primary or perhaps even secondary exchange in the field is likely to be more successful than relying on IDU to travel to a drop-in centre for supplies, as demonstrated in other settings (Irwin 2006, Burrows 2006a).

Currently available harm reduction services have had measurable benefits in Kabul, most notably in greater knowledge of injection-related health hazards among IDUs utilising NSP services. It is reassuring that NSPs were acknowledged for efforts to reduce infection risk, both through counselling and provision of new supplies. However, the inadequate geographic coverage and lack of programme resources to provide field-based outreach workers throughout the week indicate gaps that should be addressed quickly. Insufficient coverage of IDU populations by NSP programmes has been attributed to rapidly expanding concentrated HIV epidemics (Wood 2006, Bastos & Strathdee 2000, Burrows 2006b, Aceijas 2007, Wodak 2006). Similarly, NSPs are not the sole source of injecting equipment. Efforts are needed to expand availability of injection equipment at pharmacies and other sources, like mobile units, without legal reprisal (Burrows 2006b).

Aside from injecting supplies, there should be greater awareness of what potential NSP clientele perceive to be their greatest problems. The dominant theme was lack of basic survival necessities, such as food, shelter, and clothing. Based on our observations in an on-going prospective cohort assessment of NSP efficacy in Kabul, IDUs interviewed to date have consistently remarked that the best programs are those providing food, bathing and clothes washing facilities, and medical care on site. Further, there are few vocational training projects specifically for drug users and are largely geared to those who have completed treatment programs. Service uptake is strongly linked to these features, which should be included in the harm reduction package for all groups providing or planning to provide these services.

The perceived lack of addiction treatment should be addressed in scale-up of services, though quality of treatment services offered should be carefully scrutinized. We received reports in 2005 and in this study that many IDU had received treatment consisting of detoxification and motivational therapy, but that they were unable to continue attending the centre after the inpatient stay due to transportation barriers. Due to continued unemployment and lack of other improvements in their social status, many IDU quickly relapse.

The substantial influx of refugees from neighbouring countries in the last three years may have affected the local context by reducing the number of jobs available to IDU, potentially resulting in a shift to begging and stealing as the chief reported means of earning money, and the stated basic survival needs (UNHCR 2006). The more frequent mention of police harassment and fear of government entities may reflect changes in attitude towards drug users in general and IDU particularly as these government groups become more organized and more responsive to perceptions that IDU are likely to steal and conduct other illegal acts. It is concerning that a small but vocal number of those interviewed stated that police were precluding them from reaching harm reduction centres or accessing clean needles, as has been reported in Russia (Irwin 2006).

The freelist method used in this study was successful in obtaining information with minimum burden on the research subjects. Because only the freelist statement was predetermined, respondents were able to create a list using their own words and ideas, thus the data collected was open-ended and contextual in nature. Question order did not affect list length and the ability to ask consecutive freelists greatly strengthens the usefulness of this methodology, especially in hard-to-reach populations. However, the freelist method is limited by the depth of the information collected, and thus provides ‘breadth but not depth’. One example of the limitation of this information is short answers, like “convenience” mentioned as a reason to initiate injection. An additional methodologic limitation is that analysis cannot be grounded in an interpretive framework derived from the data itself due the brevity of the responses and the lack of extended probing. Only two participants elaborated about their concern for being detected by police. This concern about police detection may be more prevalent, as indicated in the 2003 survey, but may not be evoked without probing (UNODC 2003). However, this limitation is balanced by the efficiency of the freelist exercise in terms of respondent and analytic burden. Overall, based on our experience, consecutive free-list surveys appear to be an effective tool for collecting data in resource and time-limited settings, and may be considered as a modality for use in rapid assessments.

This study has other limitations that must be considered. First, results cannot be considered descriptive of all IDU in Kabul due to convenience sampling. There were no female IDU located by affiliated outreach workers, though we received reports of female IDU in Kabul. It is likely that women have different drug use practices and may not be able to access harm reduction programmes due to their extreme isolation. Future efforts should be made to safely access female IDUs to assess their needs for service provision. Also, comments made by male participants may reflect practices of female IDU that were observed in settings outside Afghanistan. Further, IDUs of higher socioeconomic status were likely not represented due to difficulties accessing this population, including the low likelihood of large social networks. Second, the relatively small sample size is sufficient for defining a cultural domain but, given the diverse experiences heightened by displacement of many IDU, some themes may have been under-represented. Sub-themes also may not be categorized in the appropriate priority order as categorization was done by the investigators based on list order, rather than pile sorting by the IDU themselves. Third, in order to obtain the greatest variety of responses, participants were asked about the experience of IDUs in general, not about their specific experiences; therefore data cannot be linked to specific respondent factors such as demographic variables. Last, the lists were administered by an interviewer, which may have resulted in socially-desirable responses. This was a necessity due to the low literacy rate and we made efforts to reduce this occurrence by hiring staff familiar with the drug using community in Kabul, phrasing list statements in the third person, and offering options for where the interview was conducted.

In conclusion, there may have been changes in the context of injection drug use in Kabul in the last four years, possibly accompanying large shifts in population composition and increasing injecting behaviour. Over this period, more harm reduction services have become available; however, demand continues to far outstrip supply and new barriers to effective implementation of these services have been identified. Our study identified reasons stated by current IDUs for engaging in high risk behaviours and perceptions of benefits and means of improvement for harm reduction programmes. Freelist methodology may be an effective way to assess context and should be considered for rapid interim assessments. Such assessments will be important as harm reduction programmes scale up in Kabul; the data presented here indicate the urgent need for improved coverage by NSP programmes and other sources of new syringes to reduce syringe sharing and continued spread of HIV and other blood borne infections.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Ministries of Counter Narcotics and Public Health, the Medicins du Monde, Nejat, and Zindagi Nawin harm reduction programmes, and the International Rescue Committee, Afghanistan, for their assistance with facilitation of this study, and our participants for their time and trust. This study was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Dr. Todd also appreciates support from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (K01TW007408).

References

- Aceijas C, Hickman M, Donoghoe MC, Burrows D, Stuikyte R. (2007) Access and coverage of needle and syringe programmes (NSP) in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Addiction, 102,1244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos FI & Strathdee SA (2000). Evaluating effectiveness of syringe exchange programmes: current issues and future prospects. Social Science and Medicine, 51,1771–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP 1999. Elicitation techniques for cultural domain analysis In Schensul J & LeCompte M (Eds.), The Ethnographer’s toolkit, vol. 3 p.115–151. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP (1999) Elicitation Techniques for Cultural Domain Analysis In: The ethnographer's toolkit, Vol. 3 Enhanced ethnographic methods audiovisual techniques, focused group interviews, and elicitation (edited by Schensul JJ). (pp.115–150), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; ). [Google Scholar]

- Bravo MJ, Barrio G, de la Fuente L, Royuela L, Domingo L, & Silva T (2003). Reasons for selecting an initial route of heroin administration and for subsequent transitions during a severe HIV epidemic. Addiction, 98, 749–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows D (2006b). Advocacy and coverage of needle exchange programmes: results of a comparative study of harm reduction programmes in Brazil, Bangladesh, Belarus, Ukraine, Russian Federation, and China. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 22, 871–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows D (2006a). Rethinking coverage of needle exchange programmes. Substance Use and Misuse, 41, 1045–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell G & Thorne J (2005). Where have all the flowers gone?: evaluation of the Taliban crackdown against opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Huo D, Bailey SL, Hershow RC, & Ouellet L (2005). Drug use and HIV risk practices of secondary and primary needle exchange users. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17, 170–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin K, Karchevsky E, Heimer R, & Badrieva L (2006). Secondary syringe exchange as a model for HIV prevention programs in the Russian Federation. Substance Use and Misuse, 41, 979–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald D & Mansfield D (2001). Afghanistan and drugs. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K (2001). Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet, 358, 483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Counter Narcotics (MoCN)/ Ministry of Public Health (MoPH). (2005) Harm Reduction Strategy for IDU (Injecting Drug Use) and HIV/AIDS Prevention in Afghanistan. Ministries of Counter-Narcotics and Public Health, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Kabul. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan M (2005). Considerations for Collecting Freelists in the Field: Examples from Ethobotany. Quinlan Field Methods, 17, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson GV, Fitch C, DesJarlais D, Poznyak V, Perlis T, Oppenheimer E, Rhodes T. (2006) Rapid assessment and response studies of injection drug use: knowledge gain, capacity building, and intervention development in a multisite study. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Maher L, & Sunjic S (1999). Transitions between routes of heroin administration: a study of Caucasian and Indochinese heroin users in south-western Sydney, Australia. Addiction, 94, 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd CS, Abed AMS, Strathdee SA, Scott PT, Botros BA, Safi N, & Earhart KC (2007). Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and associated risk behaviours among injection drug users in Kabul, Afghanistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases, In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR): UNHCR global refugee tally at 26-year low while internally displaced increase (June 9, 2006). Retrieved August 6, 2007 from: http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/4489294f4.html.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2003). Community Drug Profile #5: An assessment of problem drug use in Kabul city. Kabul, Afghanistan, UNODC. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2005). Afghanistan Drug Use Survey 2005. Kabul, Afghanistan, UNODC. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC & Romney AK (1988) Systematic Data Collection, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Chapter 2, pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak A, Cooney A. (2006) Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence. Substance Use and Misuse, 41, 777–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T. (2006) Needle exchange and the HIV outbreak among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada. Substance Use and Misuse, 41, 841–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]