This cohort study assesses the association between use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with the likelihood of testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Key Points

Question

What is the association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)?

Findings

In this cohort study of 18 472 patients, 1322 (7.2%) were taking ACEIs and 982 (5.3%) were taking ARBs. A positive COVID-19 test result was observed in 1735 (9.4%) tested patients, and among all patients with positive test results, 116 (6.7%) were taking ACEIs, and 98 (5.6%) were taking ARBs; there was no association between ACEI/ARB use and testing positive for COVID-19 (overlap propensity score–weighted odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.81-1.15).

Meaning

These data support various society guidelines to continue current treatment of chronic disease conditions with either ACEI or ARB during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abstract

Importance

The role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) in the setting of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is hotly debated. There have been recommendations to discontinue these medications, which are essential in the treatment of several chronic disease conditions, while, in the absence of clinical evidence, professional societies have advocated their continued use.

Objective

To study the association between use of ACEIs/ARBs with the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19 and to study outcome data in subsets of patients taking ACEIs/ARBs who tested positive with severity of clinical outcomes of COVID-19 (eg, hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and requirement for mechanical ventilation).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study with overlap propensity score weighting was conducted at the Cleveland Clinic Health System in Ohio and Florida. All patients tested for COVID-19 between March 8 and April 12, 2020, were included.

Exposures

History of taking ACEIs or ARBs at the time of COVID-19 testing.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Results of COVID-19 testing in the entire cohort, number of patients requiring hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and mechanical ventilation among those who tested positive.

Results

A total of 18 472 patients tested for COVID-19. The mean (SD) age was 49 (21) years, 7384 (40%) were male, and 12 725 (69%) were white. Of 18 472 patients who underwent COVID-19 testing, 2285 (12.4%) were taking either ACEIs or ARBs. A positive COVID-19 test result was observed in 1735 of 18 472 patients (9.4%). Among patients who tested positive, 421 (24.3%) were admitted to the hospital, 161 (9.3%) were admitted to an intensive care unit, and 111 (6.4%) required mechanical ventilation. Overlap propensity score weighting showed no significant association of ACEI and/or ARB use with COVID-19 test positivity (overlap propensity score–weighted odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.81-1.15).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found no association between ACEI or ARB use and COVID-19 test positivity. These clinical data support current professional society guidelines to not discontinue ACEIs or ARBs in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, further study in larger numbers of hospitalized patients receiving ACEI and ARB therapy is needed to determine the association with clinical measures of COVID-19 severity.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has developed into a pandemic since it was first identified in Wuhan, China. At the time of this writing, there have been approximately 2 million cases reported and more than 120 000 deaths (6%) due to COVID-19 across 211 countries worldwide. SARS-CoV-2 binds to the extracellular domain of the transmembrane angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to gain entry into host cells. While angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) have been shown to upregulate ACE2 expression in some animal models, there are a limited number of human studies showing mixed results on plasma ACE2 levels, and there are none on their effect on lung-specific expression of ACE2, to our knowledge. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (among other underlying disease conditions that are often treated with these agents) have been reported to have the highest case fatality rates. These observations have led to concerns that patients who are taking these medications are at an increased risk for becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 and may have worse outcomes. However, it has also been postulated that upregulation of ACE2 may improve outcomes in infection-induced acute lung injury in patients with SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-2 infections. Moreover, in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection, in certain high-risk patients, the withdrawal of ACEIs or ARBs may be harmful. Several professional societies, in the absence of sufficient clinical evidence, have recommended continued use of these medications.

We sought to clarify the potential association of ACEI and/or ARB use with the likelihood of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 test to help assess whether use of these drugs is associated with an increase in likelihood of viral infectivity, an effect that might occur with upregulation of ACE2. As the downstream pathways of ACE2 are cell protective and viral binding to ACE2 may downregulate ACE2 expression, we also aimed to determine whether ACEI or ARB use was associated with differences in clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

A retrospective cohort analysis of a prospective, observational, institutional review board–approved registry of all patients tested for COVID-19 within the Cleveland Clinic Health System in Ohio and Florida was performed. Data were extracted via previously validated automated feeds from electronic health records (EPIC; EPIC Systems Corporation) and manually by a study team trained on uniform sources for the study variables. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Cleveland Clinic. Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, medications, test results, and clinical outcomes of all patients were extracted from the registry. The exposures of interest were ACEI or ARB use as recorded in the medication list in the electronic medical records at the time of testing for SARS-CoV-2. Owing to the potentially differential effects of the 2 medication classes on ACE2 expression, exposures to ACEIs and ARBs were evaluated in separate and pooled analyses.

A waiver of informed consent (oral or written) from study participants in the COVID-19 registry was granted by the Cleveland Clinic Health System institutional review board. This cohort study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

The cohort included all patients tested for COVID-19 from March 8, 2020, to April 12, 2020. The testing protocol was modified during the course of the study owing to increasing demand and limitations of testing capabilities. Prior to March 18, the criteria for testing were less stringent (recent travel to a high-risk area, symptoms of respiratory illness, physician discretion, or a history of contact with a patient with COVID-19). Starting March 18, owing to a high demand for tests, a decision was made to prioritize testing for patients who had 2 of 3 qualifying symptoms: cough, difficulty breathing, fever (temperature >38 °C), and at least 1 of the following criteria: older than 60 years or younger than 36 months, receiving immunosuppressive therapy, cancer, end-stage kidney disease and receiving dialysis, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, lung disease, contact with an individual with COVID-19, HIV/AIDS, or solid organ transplants. After March 21, diarrhea was added to the 3 qualifying symptoms.

Testing was also available during the entire time to health care workers with temperature of more than 38 °C and/or acute respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath), and/or diarrhea and those admitted to the emergency department or the hospital.

Given previous beliefs that coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 with other respiratory viruses is rare, a reflex-testing algorithm was implemented to conserve resources. All patient specimens were first tested for the presence of influenza A/B and respiratory syncytial virus, and only those negative for influenza and respiratory syncytial virus were subsequently tested for SARS-CoV-2. Forty patients were admitted to the hospital more than once, and this analysis only includes their most severe hospital admission according to intensive care unit (ICU) status and need for mechanical ventilation.

Laboratory Confirmation

Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab specimens were collected and pooled for testing by trained medical personnel. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed by laboratory testing using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction SARS-CoV-2 assay that was validated in the Cleveland Clinic Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute. This assay used an extraction kit (MagNA Pure; Roche) and 7500 Dx Real-Time PCR System instruments (Applied Biosystems). Between March 8 and 13, 2020, the tests were sent out to LabCorp in Burlington, North Carolina. All testing was authorized by the Food and Drug Administration under an Emergency Use Authorization and in accordance with the guidelines established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19. We also performed a secondary analysis of the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 among patients with positive test results and included hospital admission, admission to the ICU, and mechanical ventilation during index hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

All descriptive statistics were reported as counts (percentages) or means (SDs). For comparison of demographic variables and comorbidities among cohorts, independent-sample t tests were used for numeric variables, while χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables.

Given that patients prescribed ACEIs or ARBs are more likely to have underlying comorbidities, overlap propensity score weighting was performed to address potential confounding. A propensity score for taking ACEIs (ARBs) was estimated from a multivariable logistic regression model containing patient age, sex, and presence of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Propensity score distributions according to ACEI and ARB usage are shown in the eFigure in the Supplement. The overlap propensity score weighting method was then applied, in which each patient’s weight is the probability of that patient being assigned to the opposite medication group. Overlap propensity score–weighted logistic regression models investigated associations between medication status and the probability of testing positive for COVID-19, as well as other clinical outcomes. As a separate analysis, patients taking either ACEIs or ARBs were combined into 1 group and compared with patients not taking either of the 2 medications. Body mass index values were missing for approximately one-third of the patients; these data are only reported descriptively in Table 1 but were not included in overlap propensity score weighting.

Table 1. Characteristics of All Patients Tested for SARS-CoV-2 and Patients Who Tested Positive by ACEI and ARB Use.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 18 472) | Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 1735) | |||||||||||

| ACEI | P value | ARB | P value | ACEI | P value | ARB | P value | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Total | 1322 (7) | 17 150 (93) | NA | 982 (5) | 17 490 (95) | NA | 116 (7) | 1619 (93) | NA | 98 (6) | 1637 (94) | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62 (16) | 48 (21) | <.001 | 65 (14) | 48 (21) | <.001 | 63 (15) | 53 (19) | <.001 | 65 (13) | 53 (19) | <.001 |

| Male | 699 (53) | 6685 (39) | <.001 | 437 (45) | 6947 (40) | .003 | 67 (58) | 792 (49) | .08 | 58 (59) | 801 (49) | .06 |

| White | 955 (72) | 11 770 (69) | <.001 | 665 (68) | 12 060 (69) | <.001 | 57 (49) | 1038 (65) | <.001 | 59 (60) | 1036 (64) | .15 |

| Black | 284 (22) | 3342 (20) | 255 (26) | 3371 (19) | 50 (43) | 369 (23) | 31 (32) | 388 (24) | ||||

| Othera | 81 (6) | 1952 (11) | 61 (6) | 1972 (11) | 9 (8) | 201 (13) | 8 (8) | 202 (12) | ||||

| BMI, >30b | 613 (54) | 4306 (41) | <.001 | 480 (55) | 4439 (41) | <.001 | 60 (59) | 399 (45) | .01 | 48 (60) | 411 (46) | .02 |

| Diabetes | 626 (48) | 2852 (17) | <.001 | 484 (50) | 2994 (17) | <.001 | 63 (54) | 269 (17) | <.001 | 48 (50) | 284 (18) | <.001 |

| CAD | 380 (29) | 1799 (11) | <.001 | 331 (34) | 1848 (11) | <.001 | 24 (21) | 137 (9) | <.001 | 23 (24) | 138 (9) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 1235 (94) | 6077 (36) | <.001 | 939 (96) | 6373 (37) | <.001 | 112 (97) | 570 (37) | <.001 | 90 (93) | 592 (38) | <.001 |

| COPD | 301 (23) | 1885 (11) | <.001 | 244 (25) | 1942 (11) | <.001 | 13 (11) | 101 (6) | .06 | 16 (16) | 98 (6) | <.001 |

| HF | 329 (25) | 1550 (9) | <.001 | 305 (32) | 1574 (9) | <.001 | 16 (14) | 130 (8) | .07 | 19 (20) | 127 (8) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; NA, not applicable; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The other category included Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic American, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, multiracial, other, or prefer not to answer

BMI data were available for 11 780 patients.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). P values were 2-sided, with a significance threshold of .05. Data analysis began April 2020.

Results

The data set consisted of 18 472 patients tested for SARS-CoV-2. The mean (SD) age was 49 (21) years, 7384 (40%) were male, and 12 725 (69%) were white. A positive COVID-19 result was observed in 1735 tested patients (9.4%). Among patients with positive test results, 421 (24.3%) were admitted to the hospital, 161 (9.3%) were admitted to an ICU, and 111 (6.4%) required mechanical ventilation. The cohort had a substantial prevalence of comorbidities: hypertension (7312 [40%]), diabetes (3478 [19%]), coronary artery disease (2179 [12%]), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2186 [12%]), and heart failure (1879 [10%]).

SARS-CoV-2 Test Positivity and ACEI and/or ARB Use

Among all tested patients, 1322 (7.2%) were taking ACEIs and 982 (5.3%) were taking ARBs. Among all patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, 116 (6.7%) were taking ACEIs and 98 (5.6%) were taking ARBs. Patients taking either ACEIs or ARBs had more comorbidities than those not taking these medications (Table 1).

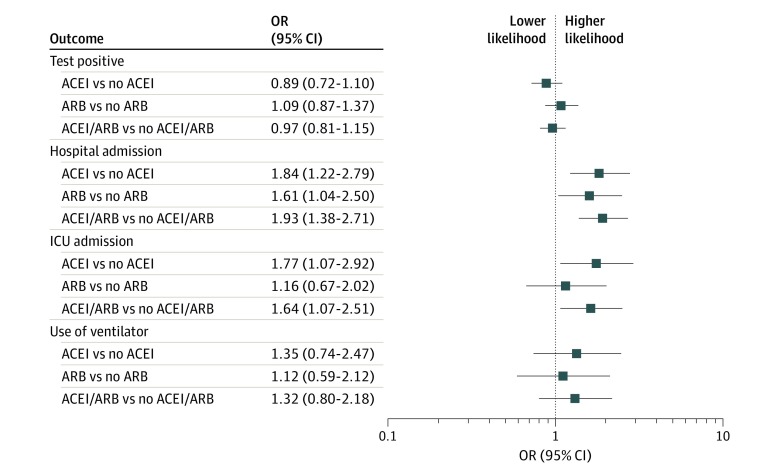

After overlap propensity score weighting for both ACEIs and ARBs, the test positivity rate was 8.6% in patients taking ACEIs compared with 9.5% in patients not taking ACEIs (overlap propensity score–weighted odds ratio [OR], 0.89; 95% CI, 0.72-1.10). Test positivity rate was 10.0% in patients taking ARBs compared with 9.3% in patients not taking ARBs (overlap propensity score–weighted OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.87-1.37) (Figure and Table 2).

Figure. Association of ACEI and ARB With Results of SARS-CoV-2 Testing (Primary Outcome) and Secondary Clinical Outcomes: Overlap Propensity Score Weighted–Analysis ORs With 95% CIs.

ACEI indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Table 2. Overlap Propensity Score–Weighted Characteristics and SARS-CoV-2 Test Positivity Among ACEI and ARB Usage Groups in All SARS-CoV-2 Tested Patients.

| Characteristic | All tested patients, %a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI | ARB | ACEI/ARB | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Count, No. | 1322 | 17 150 | 982 | 17 490 | 2285 | 16 187 |

| Age, y | 62 | 62 | 65 | 65 | 62 | 62 |

| Male | 51 | 51 | 44 | 44 | 47 | 47 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 43 | 43 |

| CAD | 28 | 28 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 29 |

| Hypertension | 93 | 93 | 95 | 95 | 93 | 93 |

| COPD | 22 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 23 |

| HF | 25 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 26 | 26 |

| Tested positive | 8.6 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 9.4 |

| OR (95% CI) | 0.89 (0.72-1.10) | 1.09 (0.87-1.37) | 0.97 (0.81-1.15) | |||

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Reported is either the overlap propensity score–weighted mean or proportion for each group.

Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Positive SARS-CoV-2 Results

Among patients with positive test results and overlap propensity score weighing, 54% taking ACEIs (vs 39% not taking ACEIs) were admitted to the hospital (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.22-2.79); 24% taking ACEIs (vs 15% not taking ACEIs) were admitted to an ICU (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.07-2.92); and 14% taking ACEIs (vs 11% not taking ACEIs) required mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.74-2.47). Similarly, among patients with positive test results and overlap propensity score weighting, 53% taking ARBs (vs 41% not taking ARBs) were admitted to the hospital (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.04-2.50); 20% taking ARBs (vs 18% not taking ARBs) were admitted to an ICU (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.67-2.02); and 14% taking ARBs (vs 12% not taking ARBs) required mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.59-2.12) (Table 3). When patients taking either ACEI or ARBs were combined into 1 group and overlap propensity score–weighted to patients not taking either of the 2 medications, the results were similar (Figure, Table 2, and Table 3).

Table 3. Overlap Propensity Score–Weighted Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes Among ACEI and ARB Usage Groups in Patients Who Tested Positive for SARS-CoV-2.

| Characteristic | All patients who tested positive, %a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI | ARB | ACEI/ARB | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Count, No. | 116 | 1619 | 98 | 1637 | 212 | 1523 |

| Age, y | 63 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 63 | 63 |

| Male | 57 | 57 | 58 | 58 | 55 | 55 |

| Diabetes | 51 | 51 | 48 | 48 | 46 | 46 |

| CAD | 21 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 |

| Hypertension | 97 | 97 | 92 | 92 | 93 | 93 |

| COPD | 12 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 |

| HF | 15 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 17 |

| Admitted to hospital | 54 | 39 | 53 | 41 | 53 | 36 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.84 (1.22-2.79) | 1.61 (1.04-2.50) | 1.93 (1.38-2.71) | |||

| Admitted to ICU | 24 | 15 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 15 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.77 (1.07-2.92) | 1.16 (0.67-2.02) | 1.64 (1.07-2.51) | |||

| Use of ventilator | 14 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 11 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.35 (0.74-2.47) | 1.12 (0.59-2.12) | 1.32 (0.80-2.18) | |||

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Reported is either the overlap propensity score–weighted mean or proportion for each group.

Deaths

Among 1705 patients with SARS-CoV-2 with death status available, 42 deaths (2.5%) occurred. Eight of 211 patients (3.8%) were in the ACEI or ARB cohort and 34 of 1494 (2.1%) were in the no-ACEI or no-ARB cohort.

Discussion

In this cohort of 18 472 patients who underwent COVID-19 testing, 2285 (12.4%) were taking ACEIs or ARBs. Taking either an ACEI or ARB was not associated with an increase in the likelihood of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure). Although unadjusted analyses suggested that taking either ACEIs or ARBs was associated with worse clinical outcomes as defined by requiring hospital admission, admission to the ICU, or requiring mechanical ventilation, it should be noted that these medications are often used in the treatment of patients with underlying chronic disease conditions. Thus, we used overlap propensity score weighting to adjust for underlying confounding factors. Overlap propensity score–weighted analysis showed a higher likelihood of hospital admission among patients with positive test results who were taking either ACEIs or ARBs. There was a higher likelihood of ICU admission among patients with positive test results who were taking ACEIs, but no such difference was observed among those taking ARBs. There was no difference in either groups with regard to requirement of mechanical ventilation during index hospitalization (Table 3). However, data with regard to clinical outcomes and measures of COVID-19 severity taking ACEIs and ARBs must be interpreted with caution and be considered only hypothesis generating, owing in part to the small sample size and the wide width of the confidence intervals in addition to the limitations of the study discussed below.

The current debate about ACEIs/ARBs and SARS-CoV-2 is based on the concern that these agents may upregulate ACE2 expression. Because SARS-CoV-2 enters into the respiratory epithelial cell by binding its viral spike protein to the extracellular domain of the structural transmembrane ACE2 receptor, these agents could potentially increase the risk of infection and worse outcomes. However, ACE2 converts angiotensin II, which promotes vasoconstriction, inflammation, and fibrosis, into angiotensin-(1-7), which may potentially protect the lung from acute injury. At present, there is no convincing evidence that ACEIs/ARBs have effects on the transmembrane ACE2 receptor in humans that would predispose to COVID-19 infection.

While the effect of ACEI/ARBs on SARS-CoV-2 infection at the molecular level is being debated, the limited amount of clinical evidence available has added to the controversy. In a retrospective study of 187 patients with COVID-19, prior use of ACEIs or ARBs (in 19 patients) was associated with elevated troponin levels, which was indirectly associated with worse clinical outcomes. However, in a study of elderly patients with hypertension with COVID-19, those taking ARBs (10 patients) had better outcomes compared with those who were taking other antihypertensive agents.

In animals, ACEIs and ARBs have different effects on cardiac membrane ACE2 activity. It would be of interest to analyze for differences in clinical outcomes among patients taking ACEIs and ARBs in future studies with larger data sets.

Limitations

With any observational study, there is a risk of confounding factors. To attempt to overcome this limitation, we performed an overlap propensity score–weighted analysis. Despite the robust initial sample size, there were few events in the ACEI or ARB users. As these data reflect test results early in the course of the pandemic, it will be of interest to repeat these analyses with larger data sets and later in the course of the pandemic. The data analyzed included information about patients receiving either ACEIs or ARBs at the time of testing but did not include information on duration of ACEI or ARB use before or after testing. Thus, we could not address the effect of duration of use of these agents or withdrawal effects after infection, eg, at the time of hospitalization. The data reflected the medication list in the electronic medical record, which may have inaccuracies owing to nonadherence to medications in the ACEI or ARB groups and nonascertainment bias from patients in the control group taking ACEIs or ARBs that was not recorded. In our secondary analyses, hospital admission was likely based on more subjective criteria than ICU admission or mechanical ventilation. There may have been a lower threshold to admit patients taking either ACEIs or ARBs or with the underlying disease conditions associated with these medications. The majority of the study population was white, which limits the generalizability of the results because there are reports of differences in expression of ACE2 among various races/ethnicities. This should be considered before extrapolating the results to other ethnic groups. It is possible that some patients who tested positive may have been subsequently admitted to a hospital outside our health care system and thus were lost to follow-up. One can reasonably expect that these patients would not introduce a bias in the study because taking ACEIs/ARBs would not influence where a person is admitted.

Conclusions

In this study of the associations of ACEI and ARB use with COVID-19 test positivity, the frequency of positive test results was not significantly different in patients taking either ACEIs or ARBs at the time of testing. ACEIs and ARBs are important medications in the management of coronary artery disease, heart failure, diabetes, and hypertension. As there may be a risk to withdrawing these agents, our study, showing no significant greater susceptibility with regard to test positivity, supports the recommendations of several professional societies that have recommended continuation of these medications. Results of the secondary analyses of association of ACEI or ARB use and markers of clinical disease severity, including hospital admission, ICU admission, or mechanical ventilation requirement, require replication and reanalysis in larger numbers of patients later in the course of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

eFigure. Propensity-score distributions according to ACEI and ARB usage status

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. ; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team . A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. Published online February 19, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450-454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishiyama Y, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Tallant EA, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. Upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 after myocardial infarction by blockade of angiotensin II receptors. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):970-976. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000124667.34652.1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2605-2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1653-1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. Published online February 24, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommerstein R. Re: Preventing a COVID-19 pandemic: ACE inhibitors as a potential risk factor for fatal COVID-19. BMJ. Published online February 28, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11(8):875-879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev Res. Published online March 4, 2020. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bavishi C, Maddox TM, Messerli FH. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and renin angiotensin system blockers. JAMA Cardiol. Published online April 3, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milinovich A, Kattan MW. Extracting and utilizing electronic health data from Epic for research. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(3):42-42. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.01.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. ; REDCap Consortium . The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F, Thomas LE, Li F. Addressing extreme propensity scores via the overlap weights. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(1):250-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. Published online March 27, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Huang F, Xu J, et al. Anti-hypertensive angiotensin II receptor blockers associated to mitigation of disease severity in elderly COVID-19 patients. Preprint. Posted online March 27, 2020. MedRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.20.20039586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Jiang Q, Xia X, et al. Individual variation of the SARS-CoV2 receptor ACE2 gene expression and regulation. Preprint. Posted online March 12, 2020. Preprints. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Propensity-score distributions according to ACEI and ARB usage status