Abstract

Background

The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is a marker of insulin resistance (IR) and has been associated with various metabolic syndromes, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases. However, limited information is available regarding its association with subclinical cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD). In this study, we evaluated the relationship between the TyG index and cSVD, including silent brain infarcts (SBIs) and white matter hyperintensity (WMH).

Methods

We assessed health check-up participants aged 40–79 years from 2006 to 2013. The TyG index was calculated using the log scale of fasting triglyceride (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2. The Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was also calculated. This was compared with two insulin surrogates and cSVD as another IR indicator and compared the association between two insulin surrogates and cSVD. SBI was measured for both prevalence and burden. The WMH volume was quantitatively rated using a computer-assisted semi-automated technique.

Results

A total of 2615 participants were evaluated (median age: 56 years, male sex: 53%). In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the TyG index was seen to be associated with SBI prevalence (adjusted odds ratio: 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06–1.81). Further quantitative analyses showed a positive dose–response relationship between the TyG index and SBI burden (P for trend = 0.006). In multivariable linear regression analysis, the TyG index was also found to be related to the volume of WMH (β = 0.084; 95% CI = 0.013 to 0.154). Additionally, the TyG index showed a similar or slightly stronger association with the prevalence of SBI and the volume of WMH than did HOMA-IR.

Conclusions

A high TyG index was associated with a higher prevalence and burden of cSVD in a neurologically healthy population. This marker of IR could be a convenient and useful predictor of cSVD.

Keywords: Triglyceride, Glucose, Insulin resistance, Leukoaraiosis, Lacunes

Background

Insulin resistance (IR) is a pathological condition that results from poor insulin sensitivity in the peripheral tissues [1]. IR increases the risk of metabolic syndromes, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately measure IR in clinical practice [1–5]. Although hyperinsulinemia-euglycemic clamps are considered to be the gold standard in quantifying insulin sensitivity, they are expensive, time-consuming, and labor intensive [6, 7]. As an alternative, the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) has been proposed. However, the HOMA-IR requires insulin levels that are not usually measured in clinical practice [8].

Patients with IR often show lipid metabolism disorders as well as glucose metabolism disorders. Excessive lipolysis causes circulating free fatty acids to increase, along with increase in the synthesis of hepatic triglyceride (TG) and very low-density lipoprotein [4, 9, 10]. Therefore, the following dyslipidemia pattern is typically seen in IR: high TG, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and high small-sized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles [1, 4, 11]. Based on this theoretical background, the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index using fasting TG and fasting glucose was suggested as a convenient IR marker, which showed a good correlation with hyperinsulinemia-euglycemic clamps and the HOMA-IR [12]. Like other IR markers, the TyG index was also found to be associated with metabolic syndromes, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, arterial stiffness, and carotid atherosclerosis [13–21]. Besides, some studies have also shown a stronger association with these conditions and the TyG index than with HOMA-IR [11, 19]. However, the relationship with subclinical cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD) is still unknown.

cSVD is a subclinical pathology that includes various pathological subtypes such as white matter hyperintensity (WMH) and silent brain infarcts (SBIs) [22]. Since cSVD increases the risk of ischemic stroke or vascular dementia [23, 24], early identification of the high-risk group is necessary. As a risk factor, many studies that have focused on the relationship between IR and cSVD have used the HOMA-IR [25, 26]. However, if a relationship can be found between the TyG index which can be obtained with a simple test and cSVD, the high-risk group will be able to be identified more easily. In this study, we examined the association between the TyG index and cSVD in a neurologically healthy population. Additionally, the association between the different subtypes of cSVD and the TyG index were examined to investigate whether IR acts as a common pathological mechanism of cSVD development or has different impacts depending on the cSVD subtypes.

Methods

Patients and population

This retrospective cross-sectional study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB number: H-1502-026-647) of Seoul National University Hospital. The requirement of written informed consent from participants was waived by the IRB for this study due to the retrospective design and because only de-identified and anonymized participant information was used. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all relevant guidelines and regulations. Any data not published within the article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Previously, we constructed a registry of consecutive health check-ups that were conducted at the Seoul National University Hospital Health Promotion Center between 2006 and December 2013 [25, 27, 28]. The health check-up registry includes medical history information that was self-reported by the participants. Additionally, laboratory results and radiological examination findings, which were conducted according to our center’s protocol were included in the final registry. As a part of this registry, participants aged 40–79 years were included (n = 3132). Among them, 64 participants with a history of stroke or a severe neurological deficit were excluded. Furthermore, we excluded participants using (1) lipid-lowering agents (n = 258), (2) glucose-lowering agents (n = 154), and those (3) missing data needed to calculate TyG index (n = 41). Finally, a total of 2615 neurologically healthy participants were included in the final cross-sectional analyses.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory assessment

We evaluated the demographic factors, clinical factors, and vascular risk factors that were measured in the routine health check-ups. Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), and use of medications (i.e., antihypertensives, antiplatelet agents) were assessed [27, 29]. Laboratory examinations were carried out after 12 h of overnight fasting, and included glucose profiles, insulin levels, lipid profiles, white blood cell (WBC) counts, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels [27, 29].

The TyG index was calculated using the log scale of [fasting TG (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2], used in previous studies [8, 19]. To compare the association between the peripheral IR (TyG index) and traditional hepatic IR (HOMA-IR) methods with cSVD, we also calculated the HOMA-IR using the following equation: glucose (mg/dL) × insulin (µU/mL)/405 [25].

Radiological assessment

All participants underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using 1.5-T MR scanners (Signa [GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA] or Magnetom SONATA [Seimens, Munich, Germany]). The detailed acquisitions of MRI were as follows: T1-weighted images, repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 500/11 ms; T2-weighted images, TR/TE = 5000/127 ms; T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, TR/TE = 8800/127 ms; and T2-gradient echo images, TR/TE = 57/20 ms. The basic slice thickness of the brain was 5 mm. SBI was defined as an asymptomatic, well-defined lesion, more than 3 mm in size with the same signal characteristics as cerebrospinal fluid on T1 and T2 images [22, 29]. We rated the burden of SBI as absent, single, or multiple, based on the number of SBI lesions present [29]. WMH volume was quantitatively rated using a computer-assisted semi-automated technique (MIPAV, version 7.3.0., National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) [27]. All radiological measurements were rated by two experienced neurologists (K.W.-N. and H.-Y.J.), who were blinded to the other clinical data. Any disagreements were resolved through a discussion with a third rater (H.-M.K.).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as a mean ± standard deviation, and those with non-normal distribution as a median [interquartile range]. Continuous variables with skewed data were transformed into a log scale, except for WMH volume, which was transformed into a square root scale due to the existence of many zero values. Since the prevalence of SBI is a binary event outcome, we conducted univariate analyses using either the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and the Chi squared or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. In the case of WMH volume, because the outcome itself is a continuous variable, we performed the univariate analysis using a simple linear regression analysis. Then, statistically significant (P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis) and clinically important (sex and BMI) variables were introduced in the multivariable analyses. Since the TyG index is itself composed of glucose and TG values, the glucose and lipid profiles were not simultaneously included in the multivariable analysis as confounders.

To assess the dose–response relationship between insulin sensitivity surrogates and SBI burden, we compared the median TyG index and HOMA-IR among participants with different burdens of SBI. In this analysis, we used the Jonckheere–Terpstra test to obtain tendencies (P for trend). The relationship between the TyG index and vascular risk factors were also examined using simple linear regression analyses. This was done to gain insights into mechanisms that show an association between the TyG index and cSVD. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Our study included a total of 2615 neurologically healthy participants (mean age: 57 years, male sex: 53%). The mean volume of WMH was 2.53 ± 5.78 mL, and SBIs were found in 209 (8%) participants. The mean value of the TyG index was 8.47 ± 0.57. Other detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1.

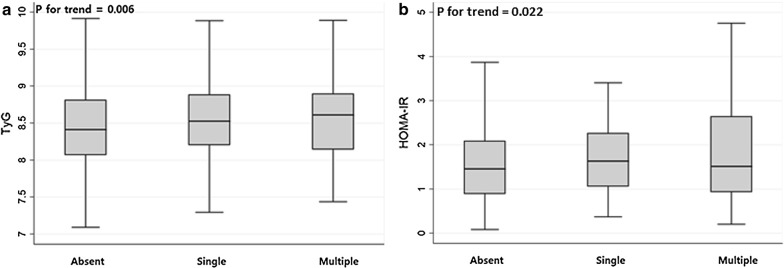

In the univariate analysis, it was found that the presence of SBIs was related to age, use of antihypertensives and antiplatelet agents, systolic and diastolic BP, level of HbA1c, fasting glucose, HOMA-IR, total/LDL/HDL cholesterol, TG, hs-CRP, and the TyG index (Table 1). In the multivariable logistic regression analyses, the TyG index was found to be significantly associated with SBI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06–1.81) after adjusting for confounders. Age (aOR = 1.09; 95% CI = 1.07–1.11) and use of antihypertensives (aOR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.00–1.97) were also related to SBI (Table 2). Compared to HOMA-IR, the TyG index had a larger aOR value and a smaller P-value, indicating a stronger association with the prevalence of SBI (Table 3). In the evaluation of the relationship between IR surrogates and the burden of SBI, patients with multiple SBI lesions had a higher TyG index (P for trend = 0.006) and HOMA-IR (P for trend = 0.022) as compared to the others, showing a dose–response manner (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of SBI (+) and SBI (−) groups

| No SBI (n = 2406) | SBI (n = 209) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [IQR] | 56 [50–62] | 63 [57–68] | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 1273 (53) | 113 (54) | 0.748 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 [IQR] | 23.89 [22.09–25.77] | 23.97 [21.99–26.09] | 0.504 |

| Use of antihypertensives, n (%) | 415 (17) | 59 (28) | < 0.001 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents, n (%) | 185 (8) | 25 (12) | 0.029 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg [IQR] | 125 [115–135] | 131 [120–142] | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg [IQR] | 75 [69–83] | 78 [70–87] | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % [IQR] | 5.7 [5.5–5.9] | 5.8 [5.5–6.2] | < 0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL [IQR] | 91 [84–99] | 92 [85–105] | 0.015 |

| Insulin, µU/mL [IQR]* | 6.5 [4.1–8.9] | 6.9 [4.6–9.7] | 0.057 |

| HOMA-IR [IQR]* | 1.46 [0.89–2.09] | 1.58 [1.01–2.34] | 0.022 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL [SD] | 203 ± 36 | 197 ± 35 | 0.030 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL [IQR] | 129 [107–151] | 121 [97–150] | 0.041 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL [IQR] | 54 [45–64] | 51 [44–61] | 0.043 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL [IQR] | 98 [72–140] | 104 [77–145] | 0.041 |

| WBC counts, × 103/μL [IQR] | 5.25 [4.34–6.30] | 5.47 [4.51–6.55] | 0.051 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dL [IQR] | 0.04 [0.01–0.14] | 0.08 [0.01–0.18] | 0.024 |

| TyG index [IQR] | 0.007 |

SBI: silent brain infarct; BP: blood pressure; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; WBC: white blood cell; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; TyG index: triglyceride-glucose index

*These variables were measured in 2051 participants

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses between possible predictors and silent brain infarct

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.09 [1.07–1.11] | < 0.001 | 1.09 [1.07–1.11] | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.05 [0.79–1.39] | 0.748 | 0.98 [0.73–1.31] | 0.872 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.02 [0.98–1.07] | 0.305 | 1.01 [0.96–1.06] | 0.835 |

| Use of antihypertensives | 1.89 [1.37–2.60] | < 0.001 | 1.41 [1.00–1.97] | 0.048 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents | 1.63 [1.05–2.54] | 0.031 | 1.01 [0.63–1.62] | 0.959 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dL* | 1.13 [1.03–1.24] | 0.008 | 1.07 [0.97–1.18] | 0.170 |

| TyG index | 1.44 [1.13–1.82] | 0.003 | 1.39 [1.06–1.81] | 0.017 |

hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; TyG index: triglyceride-glucose index

*These variables were transformed into a log scale

†Adjusted with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis (age, use of antihypertensives, use of antiplatelet agents, hs-CRP, and TyG index) and sex and BMI

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses between possible predictors and silent brain infarct/white matter hyperintensity volume using HOMA-IR instead of TyG index

| Silent brain infarct† | White matter hyperintensity‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.09 [1.07–1.11] | < 0.001 | 0.054 (0.049 to 0.059) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male | 0.87 [0.63–1.22] | 0.426 | 0.023 (− 0.063 to 0.109) | 0.601 |

| Body mass index | 0.99 [0.94–1.05] | 0.816 | − 0.012 (− 0.027 to 0.003) | 0.124 |

| Use of antihypertensives | 1.55 [1.07–2.25] | 0.021 | 0.275 (0.165 to 0.384) | < 0.001 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents | 0.93 [0.51–1.68] | 0.801 | − 0.060 (− 0.227 to 0.108) | 0.484 |

| hs-CRP* | 1.03 [0.93–1.15] | 0.553 | – | – |

| WBC counts | – | – | 0.029 (0.003 to 0.055) | 0.031 |

| HOMA-IR* | 1.32 [1.02–1.71] | 0.036 | 0.075 (0.013 to 0.137) | 0.018 |

HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC: white blood cell

*These variables were transformed into a log scale

†This analysis used a multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis (age, use of antihypertensives, use of antiplatelet agents, hs-CRP, and HOMA-IR) and sex and BMI

‡This analysis used a multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis (age, use of antihypertensives, use of antiplatelet agents, White blood cell counts, and HOMA-IR) and sex and BMI

Fig. 1.

Distributions of the insulin sensitivity surrogates according to the burden of silent brain infarcts (SBIs). Patients with multiple SBI lesions had a higher TyG index (P for trend = 0.006) and HOMA-IR (P for trend = 0.022) than those with no SBI lesions or a single lesion in a dose–response manner

The TyG index was also seen to have a close relationship with WMH volume (β = 0.084; 95% CI = 0.013 to 0.154) in the multivariable linear regression analysis. Additionally, age, use of antihypertensives, and WBC counts were positively associated with the WMH volume (Table 4). The TyG index showed similar β and P-values as that of HOMA-IR in relation to WMH volume (Table 3).

Table 4.

Simple and multiple linear regression analyses between possible predictors and white matter hyperintensity volume†

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age, years | 0.056 (0.051 to 0.060) | < 0.001 | 0.054 (0.050 to 0.059) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male | 0.025 (− 0.057 to 0.107) | 0.555 | − 0.012 (− 0.089 to 0.065) | 0.756 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | − 0.001 (− 0.014 to 0.013) | 0.935 | − 0.008 (− 0.021 to 0.005) | 0.217 |

| Use of antihypertensives | 0.384 (0.278 to 0.489) | < 0.001 | 0.168 (0.069 to 0.267) | 0.001 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents | 0.305 (0.155 to 0.455) | < 0.001 | − 0.019 (− 0.158 to 0.120) | 0.785 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.010 (0.008 to 0.013) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.008 (0.005 to 0.012) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %* | 1.022 (0.614 to 1.431) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL* | 0.648 (0.409 to 0.886) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| Insulin, µU/mL* | 0.086 (0.017 to 0.154) | 0.014 | – | – |

| HOMA-IR* | 0.104 (0.041 to 0.166) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | − 0.001 (− 0.002 to 0.000) | 0.206 | – | – |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | − 0.002 (− 0.003 to 0.000) | 0.026 | – | – |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.000 (− 0.003 to 0.003) | 0.980 | – | – |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL* | 0.088 (0.005 to 0.171) | 0.037 | – | – |

| White blood cell counts, × 103/μL | 0.051 (0.026 to 0.075) | < 0.001 | 0.040 (0.017 to 0.064) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dL* | 0.012 (− 0.015 to 0.040) | 0.378 | – | – |

| TyG index | 0.126 (0.054 to 0.198) | 0.001 | 0.084 (0.013 to 0.154) | 0.020 |

HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; TyG index: triglyceride-glucose index

*These variables were transformed into a log scale

†This variable was transformed into a square root scale

‡Adjusted with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis (age, use of antihypertensives, use of antiplatelet agents, White blood cell counts, and TyG index) and sex and BMI

The TyG index showed an association with male sex, BMI, use of antihypertensives, systolic/diastolic BP, levels of HbA1c, fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, total/LDL/HDL cholesterol, TG, hs-CRP, and WBC count (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate linear regression analysis between triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) index and risk factors

| β (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.001 (− 0.001 to 0.004) | 0.333 |

| Sex, male | 0.224 (0.181 to 0.266) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.058 (0.051 to 0.064) | < 0.001 |

| Use of antihypertensives | 0.134 (0.077 to 0.190) | < 0.001 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents | 0.064 (− 0.016 to 0.143) | 0.119 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.009 (0.007 to 0.010) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.012 (0.010 to 0.014) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %* | 2.004 (1.799 to 2.208) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL* | 1.833 (1.727 to 1.939) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin, µU/mL* | 0.358 (0.324 to 0.391) | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR* | 0.396 (0.367 to 0.426) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.003 (0.002 to 0.003) | < 0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.001 (0.000 to 0.002) | 0.020 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | − 0.017 (− 0.019 to − 0.016) | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL* | 1.100 (1.087 to 1.112) | < 0.001 |

| White blood cell counts, × 103/μL | 0.095 (0.083 to 0.108) | < 0.001 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dL* | 0.047 (0.032 to 0.061) | < 0.001 |

HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

*These variables were transformed into a log scale

Discussion

In this study, we found that a high TyG index value was associated with cSVD in a neurologically healthy population. This positive association was consistent in the analyses of both WMH volume and SBI, and even showed dose–response relationships. Thus, our findings may indicate that IR could be involved in a common mechanism of two different pathologies.

It is challenging to explain the exact mechanism behind the close association between the TyG index and cSVD. However, we can suggest several possible explanations. First, hyperplasia and hypertrophy of smooth muscle cells in the arterial walls could play a role. Insulin can cause lipohyalinosis by enhancing sympathetic activity or as a growth factor [9, 11, 16, 18]. Lipohyalinosis causes diffuse cerebral hypoperfusion or blocks small perforating arterioles causing cSVD to develop [30]. Second, endothelial dysfunction should be considered. In patients with IR, subclinical inflammation and increased oxidative stress are often observed [9, 16–18, 20, 21, 31]. A strong association between the TyG index and the WBC count/hs-CRP level was also observed in the current study (Table 5). Once the vascular endothelium is impaired by inflammation, blood contents leak into the perivascular spaces, and the solutes cannot be cleared through the blood vessel wall, resulting in cSVD [30, 32]. Third, atherosclerosis could be the link between the TyG index and cSVD. In previous studies, IR was associated with the development of atherosclerosis (i.e., atherogenesis), plaque progression, and rupture [10, 16, 18, 21, 33]. Although the relationship between the TyG index and atherosclerosis was not confirmed in this study, cSVD may develop with diffuse hypoperfusion and microembolism caused by atherosclerotic lesions [30]. Last, the close association between the TyG index and cSVD could result from other concomitant metabolic syndromes. Patients with IR often have other comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and low HDL cholesterol levels, as shown in Table 5 [1, 18, 19, 34]. Since these accompanying conditions are all risk factors for cSVD, the TyG index may reflect a combination of their effects.

Interestingly, in this study, the TyG index showed a similar or slightly stronger association with the prevalence of SBI and the volume of WMH than HOMA-IR. This finding was also observed in previous studies on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [11, 19], and might be because the TyG index and HOMA-IR reflect different aspects of IR [17, 33–35]. HOMA-IR represents hepatic IR, reflecting the ability of basal insulin to suppress hepatic glucose production [34, 35]. On the other hand, increased circulating TG interferes with normal glucose metabolism in muscles, so the TyG index mainly reflects to insulin sensitivity in the peripheral tissues (i.e., peripheral IR) [34, 35]. It is not clear how these differences lead to differences in the intensity of the association with cSVD. Previous studies have purported that this is because the TyG index has a stronger association with various bad metabolic status than HOMA-IR [34]. However, such differences do not appear to be large enough to account for the differences observed in either the current or previous studies. Further studies are needed to clarify this mechanism.

In previous studies, researchers have claimed that lowering IR could reduce the risk of subsequent strokes [1]. Researchers have also found that hepatic IR has bidirectional characteristics in its development. Contrastingly, peripheral IR progresses in a single direction from the abnormal TG/free fatty acid to reduce insulin sensitivity [35]. These findings indicate the possibility of reducing peripheral IR by treating preceded dyslipidemia [36]. Although our study has limitations as a cross-sectional study, it showed a clear relationship between the TyG index, a marker of peripheral IR, and cSVD. In the future, a study should be conducted that uses the TyG index as a therapeutic target and sees the effect on the development and progression of cSVD. Such a study may be able to provide insights that can help in the primary prevention of cerebrovascular diseases at subclinical levels.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, this study is a retrospective observational study that includes a large number of healthy participants. In selecting the study participants, we excluded people taking glucose- and lipid-lowering agents, which may cause selection bias. However, these medications can directly affect the TyG index value, which is the primary variable of this study, and these people account for only about 13% of the total health check-up registry. Thus, we think this is acceptable in interpreting our main results. Second, due to the limitations of cross-sectional analyses, causality could not be established. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings. Third, since we included a neurologically healthy population, the prevalence of SBI and the volume of WMH were relatively low. However, despite the small burdens, the association between the TyG index and cSVD was still prominent. This shows that there is a definite pathophysiological association between IR and cSVD. Last, since this study included participants that were visited over an eight-year periods from 2006 to 2013, changes in the diagnostic or experimental measurement methods may have occurred.

Conclusion

In the current study, a high TyG index was associated with a higher prevalence and burden of cSVD in a neurologically healthy population. Most participants had so-called “normal ranges” of TG and glucose levels. Nevertheless, the TyG index showed a significant association with cSVD at this subclinical level. Thus, our findings indicate that the TyG index, a useful and straightforward indicator of one’s IR state, could be a marker for the prevalence and burden of cSVD encompassing SBI and WMH of different pathologies.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Baseline characteristics of the cohort (n = 2615).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- IR

Insulin resistance

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance

- TG

Triglyceride

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- TyG index

Triglyceride-glucose index

- cSVD

Cerebral small vessel disease

- WMH

White matter hyperintensity

- SBI

Silent brain infarct

- BMI

Body mass index

- WBC

White blood cell

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Authors’ contributions

KWN and JHP designed the study. KWN, HYJ, HTK, and SMJ contributed to data acquisition. KWN performed the statistical analysis. KWN, HMK, JHP, HTK, and SMJ contributed to the discussion. KWN drafted the manuscript. HMK and JHP edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no grant support for the present study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Hospital and was carried out according to the guideline set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hyung-Min Kwon, Email: hmkwon@snu.ac.kr.

Jin-Ho Park, Email: pjhn@snu.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12933-020-01031-6.

References

- 1.Kernan W, Inzucchi S, Viscoli C, Brass L, Bravata D, Horwitz R. Insulin resistance and risk for stroke. Neurology. 2002;59(6):809–815. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick HE, Jones K, Ruotolo G, Jain AK, Henderson J, Lu W, Howard BV. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):861–867. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and incident cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2005;54(11):3252–3257. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C, Zuñiga FA. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Rutten-Jacobs L, Liu M, Markus HS, Traylor M. Causal impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on cerebral small vessel disease: a mendelian randomization analysis. Stroke. 2018;49(6):1325–1331. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo E, Wang D, Yan G, Qiao Y, Liu B, Hou J, Tang C. High triglyceride–glucose index is associated with poor prognosis in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Xu L, Liu X, Wang Y. Evaluation of insulin sensitivity by hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps using stable isotope-labeled glucose. Cell Discov. 2018;4(1):17. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao S, Yu S, Chi C, Fan X, Tang J, Ji H, Teliewubai J, Zhang Y, Xu Y. Association between macro-and microvascular damage and the triglyceride glucose index in community-dwelling elderly individuals: the Northern Shanghai Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0898-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez-Íñigo L, Navarro-González D, Pastrana-Delgado J, Fernández-Montero A, Martínez JA. Association of triglycerides and new lipid markers with the incidence of hypertension in a Spanish cohort. J Hypertens. 2016;34(7):1257–1265. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su W-Y, Chen S-C, Huang Y-T, Huang J-C, Wu P-Y, Hsu W-H, Lee M-Y. Comparison of the effects of fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and triglyceride-glucose index on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2838. doi: 10.3390/nu11112838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jian S, Su-Mei N, Xue C, Jie Z, Xue-sen W. Association and interaction between triglyceride–glucose index and obesity on risk of hypertension in middle-aged and elderly adults. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39(8):732–739. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2017.1324477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metabolic Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6(4):299–304. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Silva A, Caldas APS, Hermsdorff HHM, Bersch-Ferreira ÂC, Torreglosa CR, Weber B, Bressan J. Triglyceride-glucose index is associated with symptomatic coronary artery disease in patients in secondary care. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee EY, Yang HK, Lee J, Kang B, Yang Y, Lee S-H, Ko S-H, Ahn Y-B, Cha BY, Yoon K-H. Triglyceride glucose index, a marker of insulin resistance, is associated with coronary artery stenosis in asymptomatic subjects with type 2 diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0324-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Won K-B, Park G-M, Lee S-E, Cho I-J, Kim HC, Lee BK, Chang H-J. Relationship of insulin resistance estimated by triglyceride glucose index to arterial stiffness. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0914-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bornfeldt KE, Tabas I. Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MK, Ahn CW, Kang S, Nam JS, Kim KR, Park JS. Relationship between the triglyceride glucose index and coronary artery calcification in Korean adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0589-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi W, Xing L, Jing L, Tian Y, Yan H, Sun Q, Dai D, Shi L, Liu S. Value of triglyceride-glucose index for the estimation of ischemic stroke risk: insights from a general population. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(2):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SB, Ahn CW, Lee BK, Kang S, Nam JS, You JH, Kim MJ, Kim MK, Park JS. Association between triglyceride glucose index and arterial stiffness in Korean adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0692-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Won K-B, Kim YS, Lee BK, Heo R, Han D, Lee JH, Lee S-E, Sung JM, Cho I, Park H-B. The relationship of insulin resistance estimated by triglyceride glucose index and coronary plaque characteristics. Medicine. 2018;97(21):e10726. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao Q, Zhou D, Li Y, Wang Y, Xu S-C, Zhao X-H. The triglyceride-glucose index predicts coronary artery disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-st-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:6891537. doi: 10.1155/2019/6891537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, Lindley RI, T O’Brien J, Barkhof F, Benavente OR. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E-J, Kang D-W, Warach S. Silent new brain lesions: innocent bystander or guilty party? J Stroke. 2016;18(1):38. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.01410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Román GC, Erkinjuntti T, Wallin A, Pantoni L, Chui HC. Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(7):426–436. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JE, Shin DW, Yun JM, Kim SH, Nam Y-S, Cho B, Lim J-S, Jeong H-Y, Kwon H-M, Park J-H. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for silent lacunar infarction. Stroke. 2016;47(12):2938–2944. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Zhang S, Dong Z, Zi Y, Luo Y, Jin Z, Shi L, Li C, Ren C, Wu D. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for overall cerebral small vessel disease burden in old nondiabetic healthy adult population. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:127. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam K-W, Kwon H-M, Jeong H-Y, Park J-H, Kwon H, Jeong S-M. Serum homocysteine level is related to cerebral small vessel disease in a healthy population. Neurology. 2019;92(4):e317–e325. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam K-W, Kwon H-M, Jeong H-Y, Park J-H, Kwon H, Jeong S-M. Cerebral small vessel disease and stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1210–1216. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam K-W, Kwon H-M, Jeong H-Y, Park J-H, Kim SH, Jeong S-M. Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase is associated with silent brain infarcts in a healthy population. Atherosclerosis. 2019;280:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(7):689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan Z, Yu D, Cai Y, Shang J, Qin R, Xiao J, Zhao B, Zhao Z, Simmons D. Triglyceride glucose index predicting cardiovascular mortality in Chinese initiating peritoneal dialysis: a cohort study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2019;44(4):669–678. doi: 10.1159/000500979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y, Wardlaw JM. Update on cerebral small vessel disease: a dynamic whole-brain disease. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2016;1(3):83–92. doi: 10.1136/svn-2016-000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alizargar J, Bai C-H. Comparison of carotid ultrasound indices and the triglyceride glucose index in hypertensive and normotensive community-dwelling individuals: a case control study for evaluating atherosclerosis. Medicina. 2018;54(5):71. doi: 10.3390/medicina54050071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irace C, Carallo C, Scavelli F, De Franceschi M, Esposito T, Tripolino C, Gnasso A. Markers of insulin resistance and carotid atherosclerosis. A comparison of the homeostasis model assessment and triglyceride glucose index. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(7):665–672. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han T, Cheng Y, Tian S, Wang L, Liang X, Duan W, Na L, Sun C. Changes in triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol may precede peripheral insulin resistance, with 2-h insulin partially mediating this unidirectional relationship: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0469-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin J-L, Cao Y-X, Wu L-G, You X-D, Guo Y-L, Wu N-Q, Zhu C-G, Gao Y, Dong Q-T, Zhang H-W. Triglyceride glucose index for predicting cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(11):6137. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.10.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Baseline characteristics of the cohort (n = 2615).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.