Channelrhodopsin-2 is the key ion channel in optogenetics. Walther et al. demonstrate that coupling channelrhodopsin-2 to the β1 subunit of voltage-gated sodium channels allows action potentials to be triggered by blue-light illumination of Xenopus laevis oocytes coexpressing different types of sodium channel α subunits.

Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium (Na+) channels are responsible for the fast upstroke of the action potential of excitable cells. The different α subunits of Na+ channels respond to brief membrane depolarizations above a threshold level by undergoing conformational changes that result in the opening of the pore and a subsequent inward flux of Na+. Physiologically, these initial membrane depolarizations are caused by other ion channels that are activated by a variety of stimuli such as mechanical stretch, temperature changes, and various ligands. In the present study, we developed an optogenetic approach to activate Na+ channels and elicit action potentials in Xenopus laevis oocytes. All recordings were performed by the two-microelectrode technique. We first coupled channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), a light-sensitive ion channel of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, to the auxiliary β1 subunit of voltage-gated Na+ channels. The resulting fusion construct, β1-ChR2, retained the ability to modulate Na+ channel kinetics and generate photosensitive inward currents. Stimulation of Xenopus oocytes coexpressing the skeletal muscle Na+ channel Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 with 25-ms lasting blue-light pulses resulted in rapid alterations of the membrane potential strongly resembling typical action potentials of excitable cells. Blocking Nav1.4 with tetrodotoxin prevented the fast upstroke and the reversal of the membrane potential. Coexpression of the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv2.1 facilitated action potential repolarization considerably. Light-induced action potentials were also obtained by coexpressing β1-ChR2 with either the neuronal Na+ channel Nav1.2 or the cardiac-specific isoform Nav1.5. Potential applications of this novel optogenetic tool are discussed.

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium (Na+) channels initiate the rapid upstroke of action potentials (APs) in excitable cells. These channels are heteromultimeric proteins consisting of a large pore-forming α subunit (∼260 kD) and smaller accessory β subunits (Goldin et al., 2000; Goldin, 2001; Brackenbury and Isom, 2011; Catterall, 2017). The α subunit determines the main electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of a given Na+ channel complex, while β subunits modulate the function of α subunits.

The α subunit is composed of four homologous domains (DI–DIV) that are connected by intracellular linkers. Each domain contains six transmembrane segments. The fourth segment (S4) of each domain is an essential element of the voltage sensor. A depolarizing voltage pulse leads to a transient outward movement of the S4s, thereby initiating the opening of the pore. The large Na+ conductance of 10–30 pS (Sigworth and Neher, 1980; Bezanilla, 1987) finally allows for the fast AP upstroke. The ensuing transition from the open to the inactivated state occurs within a few milliseconds after opening. This so-called open-state inactivation is mediated by an intracellularly located inactivation gate, formed by the DIII–DIV linker. The termination of the Na+ influx and the activation of voltage-gated K+ channels limit the AP amplitude and allow for fast repolarization. Nine different functional Na+ channel α subunits have been identified by electrophysiological recordings, biochemical purification, and cloning studies (Goldin et al., 2000; Goldin, 2001). The α subunits Nav1.1, Nav1.2, and Nav1.3 are the major isoforms of the central nervous system, Nav1.4 is mainly expressed in skeletal muscle, Nav1.5 is the cardiac isoform, Nav1.6 is widely expressed in various neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system, and Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 are expressed primarily in the peripheral nervous system. According to their binding affinity for the puffer fish poison tetrodotoxin (TTX), voltage-gated Na+ channels have been classified into two pharmacologically different groups: cardiac Nav1.5 as well as neuronal Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 channels are resistant to nanomolar TTX concentrations (half-maximal inhibitory concentration [IC50], ∼1–6 µM; Gellens et al., 1992; Goldin, 2001). The other neuronal Na+ channels as well as the skeletal muscle channel Nav1.4 are highly sensitive toward TTX (IC50 ∼10 nM; Goldin, 2001).

Four distinct β subunits have been found in various excitable tissues. They are glycosylated membrane proteins composed of a larger N-terminal extracellular region that is connected via a single transmembrane segment to a smaller C-terminal intracellular domain. The β1 subunit is expressed in all excitable tissues including brain, dorsal root ganglia, sciatic nerve, spinal cord, skeletal muscle, and throughout the heart (Sutkowski and Catterall, 1990; Isom et al., 1992; Brackenbury and Isom, 2011). It functionally interacts with multiple Na+ channel α subunits (Patton et al., 1994) shifts steady-state gating, accelerates Na+ current decay kinetics, and facilitates recovery from inactivation of Na+ channel α subunits (Isom et al., 1992; Nuss et al., 1995; Zimmer and Benndorf, 2002).

Channelrhodopsins represent the only directly light-gated ion channels in nature (Nagel et al., 2002, 2003; Schneider et al., 2015). The cDNAs for channelrhodopsin-1 and channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) were discovered in a data bank of expressed sequence tags from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and identified as partially homologous to the light-driven H+-pump bacteriorhodopsin. Both proteins were characterized in detail after heterologous expression in oocytes of Xenopus laevis (Nagel et al., 2002, 2003). ChR2 was also successfully expressed in mammalian cells and shown to confer light-induced depolarization via light-activatable cation permeability in these cells (Nagel et al., 2003). This seven-transmembrane helix protein is mainly permeable for protons, less for sodium and potassium, and also for calcium (Nagel et al., 2003). It consists of an opsin as the apoprotein and the chromophore retinal, which is connected via protonated Schiff-base linkage to lysine 257. Naturally, ChR2 occurs in dimers; the respective interaction is mediated by helices 3 and 4 and a disulfide bond of cysteines on the extracellular N-termini (Volkov et al., 2017). The pore is formed by helices 1, 2, 3, and 7. Blue-light illumination causes retinal isomerization leading to conformational changes that open the pore for cation influx (Berndt et al., 2011). The photocycle for ChR2 can be explained by a four-state model considering two conducting and two dark nonconducting states (Schneider et al., 2015; Deisseroth and Hegemann, 2017).

Since five groups independently expressed ChR2 in neurons and showed strong light-effects, the new field of optogenetics rapidly evolved, because of the opportunity to control specific cells noninvasively by blue light (Boyden et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Nagel et al., 2005; Bi et al., 2006; Ishizuka et al., 2006). In this novel research field, endogenous voltage-gated ion channels of excitable cells are activated by ChR2-mediated membrane depolarization, resulting in blue light–triggered APs. Driven by the potential of this method, scientists mutated ChR2 to obtain variants with increased potency and light sensitivity (Berndt et al., 2011; Ullrich et al., 2013; Schneider et al., 2015). One of the mutants, T159C, produces large photocurrents by stabilizing the Schiff-base linkage of retinal to lysine 257 (Ullrich et al., 2013). Despite all the important progress in recent years, ChR2 and all its variants are still characterized by an extremely small conductance that is too small to be determined experimentally. Estimates assume a single-channel conductance of 40–60 fS (Nagel et al., 2003; Feldbauer et al., 2009), which is almost three orders of magnitude smaller than the conductance of a voltage-gated Na+ channel. Additionally, ChR2 does not have any localization preference in the plasma membrane of target cells, i.e., it does not specifically localize at regions with a high density of voltage-gated Na+ channels, like the axon hillock of neurons or the intercalated disc region of cardiac myocytes.

In the present study, we introduce an optogenetic tool by combining ChR2-mediated membrane depolarization with the vast conductance of a voltage-gated Na+ channel. By direct coupling of ChR2 to one of the Na+ channel β subunits, we were able to evoke artificial APs in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing brain-, muscle-, or heart-type Na+ channel α subunits. This enables us to shape APs in naturally unexcitable cells, as similarly shown recently by a current injection method (Corbin-Leftwich et al., 2016, 2018). Our novel optogenetic approach with β1-ChR2 provides the potential for noninvasive excitation.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and recombinant DNA procedures

For the expression of Nav1.2 (brain IIA; GenBank accession nos. X03639 and X61149), Nav1.4 (GenBank accession no. AJ278787), Nav1.5 (GenBank accession no. M77235), β1 (GenBank accession no. M91808), Kv2.1 (GenBank accession no. X68302), and ChR2 (GenBank accession no. AF461397), the following plasmids were used: pNa200 (Auld et al., 1988; kindly provided by Dr. A.L. Goldin, University of California, Irvine, CA), pSP64T-mNav1.4 (Zimmer and Benndorf, 2007), pTSV40G-hNav1.5 (Walzik et al., 2011), pGEM-β1 (Zimmer and Benndorf, 2002), pGEMHE-hKv2.1 (h-DRK1; Koopmann et al., 2001), and pGEMHE-ChR2-T159C::YFP (Berndt et al., 2011; Ullrich et al., 2013). The ChR2-T159C mutant showing an enhanced binding affinity to the endogenous retinal of oocytes was used throughout the study.

The ChR2-Nav1.5 fusion was constructed by overlapping PCR. First, we amplified the ChR2-T159C cDNA, encoding M1 to V309, and a short N-terminal hNav1.5 fragment, encoding M1 to K98, in separate reactions. The second recombinant PCR step resulted in a 1.3-kb fragment that was digested by HindIII (incorporated into the ChR2 forward primer) and SdaI (present in the hNav1.5 cDNA). Both sites were used to insert the chimeric fragment into pTSV40G-hNav1.5. The resulting plasmid, pTSV40G-ChR-hNav1.5, was expected to encode the following channel protein: ChR2/T159CM1-V309-hNav1.5M1-V2016 (ChR-Nav1.5 in Fig. 1).

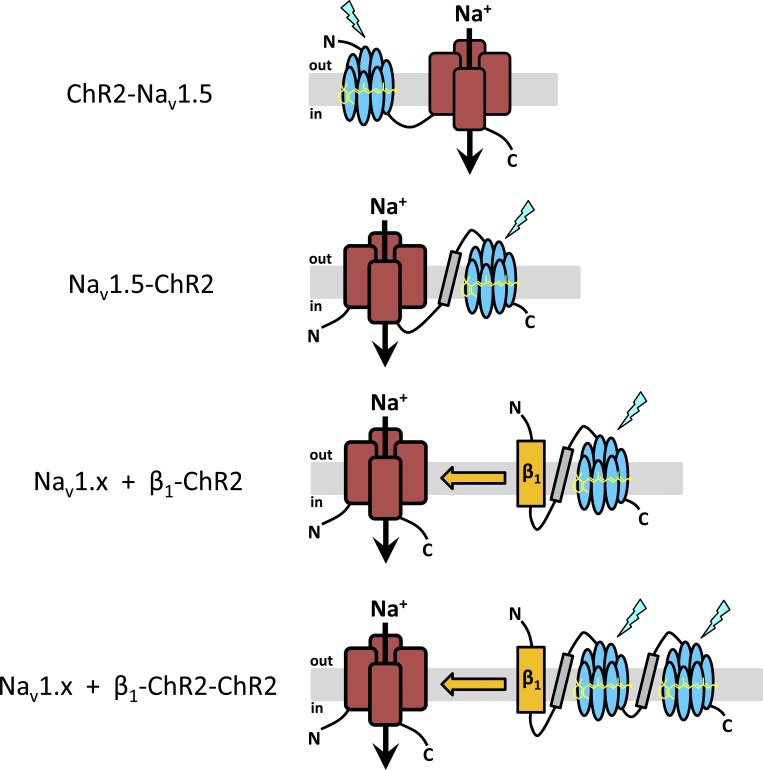

Figure 1.

Experimental strategy. The purpose of our study was to elicit light-induced APs not by coexpression of wild type ChR2 with voltage-gated Na+ channels, but by coupling ChR2 either directly to Nav1.5 (ChR2-Nav1.5, Nav1.5-ChR2) or to the accessory β1 subunit (β1-ChR2, β1-ChR2-ChR2). The seven transmembrane regions of ChR2 (blue), the four large domains of voltage-gated Na+ channels (red), the β1 subunit (orange), and the membrane-spanning region of the human H+/K+ATPase (gray) are illustrated. In Nav1.5-ChR2, β1-ChR2, and β1-ChR2-ChR2, peptide [GGGS]3 was incorporated into all linker regions (symbolized by a black line). For detailed amino acid composition of the constructs, see Materials and methods.

For the construction of β1-ChR2, first we purchased a synthetic DNA fragment (Invitrogen) coding for the following chimeric protein: full-length human Na+ channel β1 subunit (hβ1; GenBank accession no. L16242), linker GGGS-GGGS-GGGS ([GGGS]3), transmembrane region A2 to N103 of the β subunit of the human H+/K+-ATPase (hβHKA2-N103; GenBank accession no. NM_000705), and linker region [GGGS]3. The coding region of ChR2 mutant T159C (ChR2/T159C), lacking the putative signal sequence M1 to V23 and the C-terminal region N310 to E737, was finally coupled in-frame by a recombinant PCR approach. The resulting construct was subcloned into the BamHI/XbaI sites of oocyte expression vector pGEMHEnew, resulting in pGEM-β1-ChR2. The expected amino acid sequence of β1-ChR2 is as follows: hβ1M1-E218-[GGGS]3-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309 (β1-ChR2 in Fig. 1). The sequence of the YFP was coupled in-frame to the C-terminus of β1-ChR2 by recombinant PCR, thereby incorporating also a Golgi-to-plasma membrane trafficking signal (Hofherr et al., 2005) and an ER export motif (Stockklausner et al., 2001). The resulting plasmid pGem-β1-ChR2-YFP was analyzed by suitable restriction enzymes and DNA sequencing. The expected amino acid sequence of the coding region is as follows: hβ1M1-E218-[GGGS]3-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309-[KSRITSEGEYIPLDQIDINVVDTSSR]-YFPM1-K239-[SRFCYENEV].

To obtain β1-ChR2-ChR2, we first exchanged the stop codon in pGEM-β1-ChR2 by a short sequence coding for linker region GGGSR using a respectively designed PCR primer. The resulting vector, pGEM-β1-ChR2*, still contained the XbaI and HindIII sites to allow for downstream coupling of the second ChR2 cDNA. The respective 1.3-kb fragment, separately amplified by PCR from pGEM-β1-ChR2, was expected to encode for the following amino acid sequence: [GGGS]2-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309. An XbaI site was incorporated in the forward and a HindIII site in the reverse primer so that the PCR fragment obtained could be finally subcloned into pGEM-β1-ChR2*. The resulting plasmid, pGEM-β1-ChR2-ChR2, was used to produce the β1-ChR2-ChR2 cRNA and finally the following channel protein: hβ1M1-E218-[GGGS]3-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309-GGGSR-[GGGS]2-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309 (β1-ChR2-ChR2 in Fig. 1).

The Nav1.5-ChR2 fusion was also constructed by overlapping PCR. First, we amplified in separate reactions a 0.4-kb fragment (expected to encode hNav1.5R2012-V2016-[GGGS]3-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-E31) using pGEM-β1-ChR2, a 0.9-kb fragment (expected to encode ChR2/T159CN24-V309) using pGEM-β1-ChR2, and a short C-terminal hNav1.5 fragment (expected to encode hNav1.5R1897-V2016-GGGSG) using expression plasmid pTSV40G-hNav1.5. The recombinant PCR step resulted in a 1.6-kb fragment that was digested by Tth111I (present in the hNav1.5 cDNA) and NotI (incorporated into the ChR2 reverse primer downstream to the stop codon). Both restriction sites were used to insert the chimeric fragment into pTSV40G-hNav1.5. The resulting plasmid, pTSV40G-hNav1.5-ChR2, was used to produce the Nav1.5-ChR2 cRNA and finally the following channel protein: hNav1.5M1-V2016-[GGGS]3-hβHKA2-N103-[GGGS]3-ChR2/T159CN24-V309 (Nav1.5-ChR2 in Fig. 1).

A thermostable DNA polymerase with proofreading activity was used for all PCR reactions (Pfu DNA polymerase, Promega). The correctness of PCR-derived sequences was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Seqlab Microsynth).

Heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes

In vitro transcription was done using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Transcription Kit (Life Technologies) after linearization with NotI, XbaI, or NheI (pGEM-derived plasmids, pNa200, and pTSV40G-hNav1.5), and the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 Transcription Kit (Life Technologies) after linearization with NotI (pSP64T-mNav1.4). We used pGEMHE-ChR2-T159C::YFP as the ChR2 control plasmid (NheI digestion and T7 promoter for in vitro transcription). The quality of the cRNA was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis; the concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Xenopus oocytes obtained from EcoCyte Bioscience were injected with 50–70 nl of cRNA and incubated at 18°C for 48–72 h in Barth medium (in mM: 84 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 0.82 MgSO4, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, and 7.5 Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) containing 1 µM all-trans Retinal (Sigma). At least four different batches of oocytes were tested for each construct and construct combination.

Electrophysiological recordings and fluorescence imaging

All recordings were performed at room temperature with the two-microelectrode technique using the TEC-05-S amplifier from npi Electronic Instruments, as previously described (Gütter et al., 2013). The following bath solution was used (in mM): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES/KOH, pH 7.4 (Gütter et al., 2013). Glass microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl. Microelectrode resistance was between 0.1 and 0.6 MΩ. Membrane resistance of injected oocytes was calculated from the leak current difference at −120 and −80 mV in the voltage-clamp mode. Oocytes with a resistance <100 kΩ were excluded (for mean values and oocyte variability, see Table S1 and Table S2). Recording and analysis of the data were performed on a personal computer with ISO3 software (MFK). The sampling rate was 5 kHz, except for the whole-cell Na+ channel measurements (20–50 kHz). Student’s t test was used to test for statistical significance. Statistical significance was assumed for P < 0.05.

Currents through Na+ channels were elicited by test potentials from −80 to 50 mV in 5- or 10-mV increments at a pulsing frequency of 1.0 Hz (holding potential −120 mV). Steady-state activation (m∞) was evaluated by fitting the Boltzmann equation m∞ = {1 + exp[−(V − Vm)/s]}−1 to the normalized conductance as function of voltage. Steady-state inactivation (h∞) was determined with a double-pulse protocol consisting of 500-ms prepulses to voltages between −140 and −30 mV followed by a constant test pulse of 10-ms duration to −20 mV at a pulsing frequency of 0.5 Hz. The amplitude of peak INa during the test pulse was normalized to the maximum peak current and plotted as function of the prepulse potential. Data were fitted to the Boltzmann equation h∞ = {1 + exp[(V − Vh)/s]}−1, where V is the test potential, Vm and Vh are the midactivation and midinactivation potentials, respectively, and s is the slope factor in mV. Recovery from inactivation was determined with a double-pulse protocol consisting of a 500-ms prepulse to −10 mV, a variable recovery interval at −120 mV, and a second test pulse of 20 ms duration to −20 mV at a pulsing frequency of 0.2 Hz. Recovery of Nav1.4 channels was analyzed by fitting data using the two-exponential equation I = 1 − [A1 × exp(−t/τ1) + A2 × exp(−t/τ2)], where I is the normalized current, t is the recovery time, and τ1 and τ2 are time constants of fast- and slow-recovering components, respectively. Currents through K+ channels were elicited by test potentials from −70 to 50 mV in 10-mV increments at a pulsing frequency of 1.0 Hz (holding potential −80 mV).

Blue-light pulses for the activation of ChR2 (maximum at 472 nm) were delivered to the oocytes via a light guide mounted to a self-made LED device (internal workshop). In voltage-clamp experiments, the holding potential was set to −80 mV. APs were recorded in the current-clamp mode after setting the resting membrane potential from approximately −30 to −80 mV by an appropriate current injection. Light intensity was measured by the LaserCheck power meter from Coherent. Measurements resulted in 7.1 mW/mm2. Light pulses were elicited by the respective trigger function implemented in ISO3.

To analyze cell surface expression of YFP-labeled ChR2 and β1-ChR2, oocyte images were recorded under identical settings by a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM710; Carl Zeiss) using an EC Plan-Neofluar 10×/0.3 M27 objective. YFP in both fusion proteins was excited by the 514-nm line of the argon laser and detected in the 517–581-nm range. Received 12-bit images show a confocal slice of an oocyte. The mean intensity of the whole images was analyzed by the implemented tool in the ZEN 2010 software. Mean intensity of noninjected cells was subtracted.

Online supplemental material

Figs. S1 and S2 show superimposed current-clamp recordings for Nav1.4- and Nav1.5-mediated APs in Xenopus oocytes, respectively. Both figures illustrate the variability of the light-induced APs. Table S1 and Table S2 show the corresponding values for the oocyte membrane resistance, the size of the photocurrent, the peak Na+ current, the K+ current, and several AP parameters (threshold, overshoot, 10–90% rise time, and AP duration for two above-threshold voltages).

Results

Direct coupling of ChR2 to Nav1.5

To place ChR2 next to a sodium channel, we coupled ChR2 first to the N- or C-terminus of the human cardiac voltage-gated Na+ channel Nav1.5, resulting in ChR2-Nav1.5 and Nav1.5-ChR2, respectively (Fig. 1). In ChR2-Nav1.5, the C-terminus of ChR2 was directly linked to the N-terminus of Nav1.5. In Nav1.5-ChR2, we incorporated the transmembrane N-terminal helix of the β subunit of the human H+/K+-ATPase as a membrane-spanning region between the intracellularly exposed C-terminus of Nav1.5 and the extracellular N-terminus of ChR2, as successfully demonstrated in an earlier study (Kleinlogel et al., 2011).

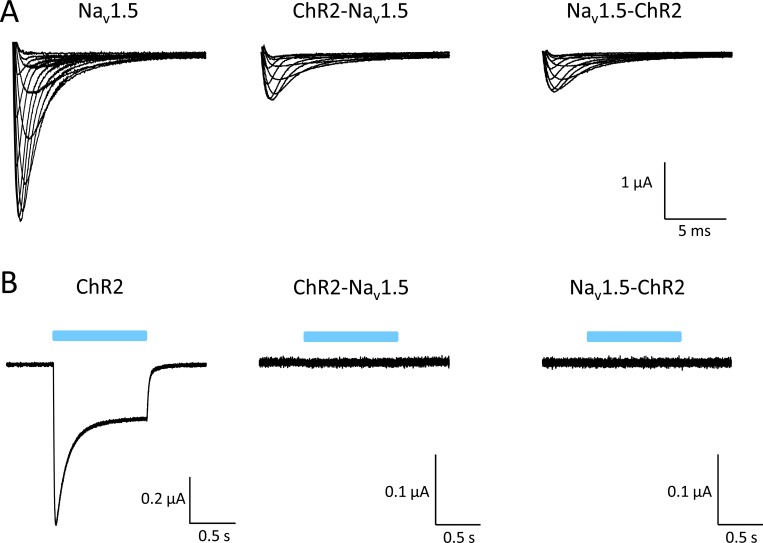

Expression in Xenopus oocytes of both ChR2-Nav1.5 and Nav1.5-ChR2 resulted in voltage-activated Na+ currents (Fig. 2 A). However, peak Na+ current amplitudes were significantly reduced, even when injecting a much higher cRNA amount per oocyte. Subsequent blue-light exposure of the oocytes failed to trigger typical ChR2 currents, suggesting that the ChR2 domain was not functional in both fusion proteins (Fig. 2 B). Because similar data were obtained in HEK293 cells (not depicted), we concluded that both fusion constructs cannot be functionally expressed in a heterologous host.

Figure 2.

Electrophysiological test for functional expression of ChR-Nav1.5 and Nav1.5-ChR2 in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Representative whole-cell currents generated by wild type Nav1.5, ChR2-Nav1.5, and Nav1.5-ChR2 at test potentials between −45 and +20 mV. Injected amount of cRNA per oocyte: 0.1 ng Nav1.5, 10 ng ChR2-Nav1.5, and 10 ng Nav1.5-ChR2. Peak current density for Nav1.5 was 1.56 ± 0.1 µA (n = 10). Current reduction was similar in ChR2-Nav1.5 and Nav1.5-ChR2 (0.59 ± 0.08 µA with n = 21 versus 0.71 ± 0.07 µA with n = 27, respectively; P < 0.05 versus Nav1.5). (B) None of the ChR2 fusions responded to a 1-s blue-light pulse. Injected amount of cRNA per oocyte: 0.2 ng ChR2, 10 ng ChR2-Nav1.5, and 10 ng Nav1.5-ChR2.

Coupling of ChR2 to the Na+ channel β1 subunit

Next, we linked ChR2 to the C-terminus of the β1 subunit of voltage-gated Na+ channels (Fig. 1). The specific interaction of this accessory subunit with its α subunit should direct the ChR2 moiety in close proximity to the Na+ channel, thereby forming a light-sensitive channel complex: blue light–pulses should first activate ChR2, resulting in a small inward flux of positive ions. We hypothesized that the resulting slight membrane depolarization could be sufficient to exceed the threshold potential for voltage-gated Na+ channels and thus to elicit an AP upstroke.

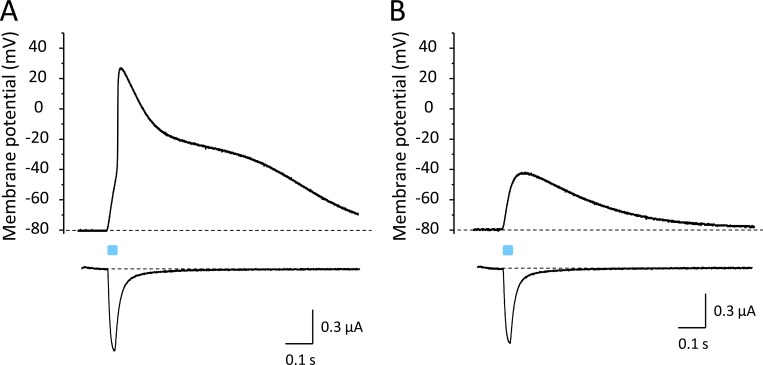

As a first step, we tested whether both β1 and ChR2 are functional in the fusion β1-ChR2. As shown in Fig. 3 A, blue light delivered to β1-ChR2–injected oocytes induced typical ChR2 inward currents. However, peak currents were significantly reduced from 6.09 ± 0.51 µA in ChR2 to 0.65 ± 0.07 µA in β1-ChR2 when injecting oocytes with 10 ng cRNA (Fig. 3 B). The ratio between peak and plateau current remained unchanged (see legend to Fig. 3). Similar data were obtained when coupling a second ChR2 to β1-ChR2. Using β1-ChR2-ChR2, we found peak current amplitudes of 0.65 ± 0.10 µA (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Whole-cell currents through ChR2, β1-ChR2, and β1-ChR2-ChR2 channels. (A) Linkage of the C-terminus of the β1 subunit to the N-terminus of ChR2 resulted in typical light-induced inward currents in the voltage-clamp mode. The plateau current relative to the transient current was similar for all three channels (52.9 ± 7.6% in ChR2, 42.8 ± 8.2% in β1-ChR2, and 42.0 ± 10.8% in β1-ChR2-ChR2). (B) Currents were significantly reduced when injecting 10 ng cRNA per oocyte. Notably, coupling of a second ChR2 did not alter expression (possible reasons are discussed in the text). Number of measurements were n = 27 (ChR2), n = 20 (β1-ChR2), and n = 21 (β1-ChR2-ChR2; *, P < 0.05 versus ChR2). Error bars represent SEM.

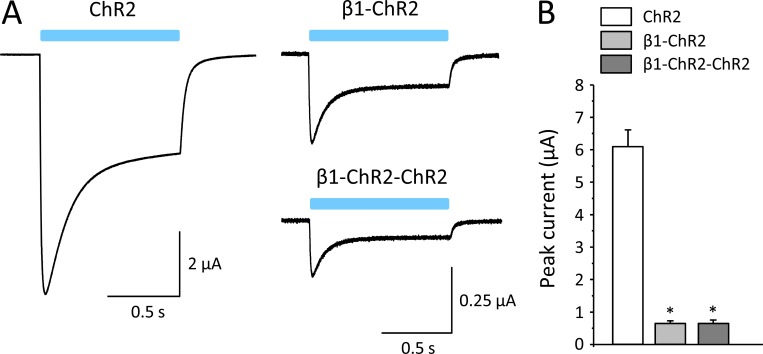

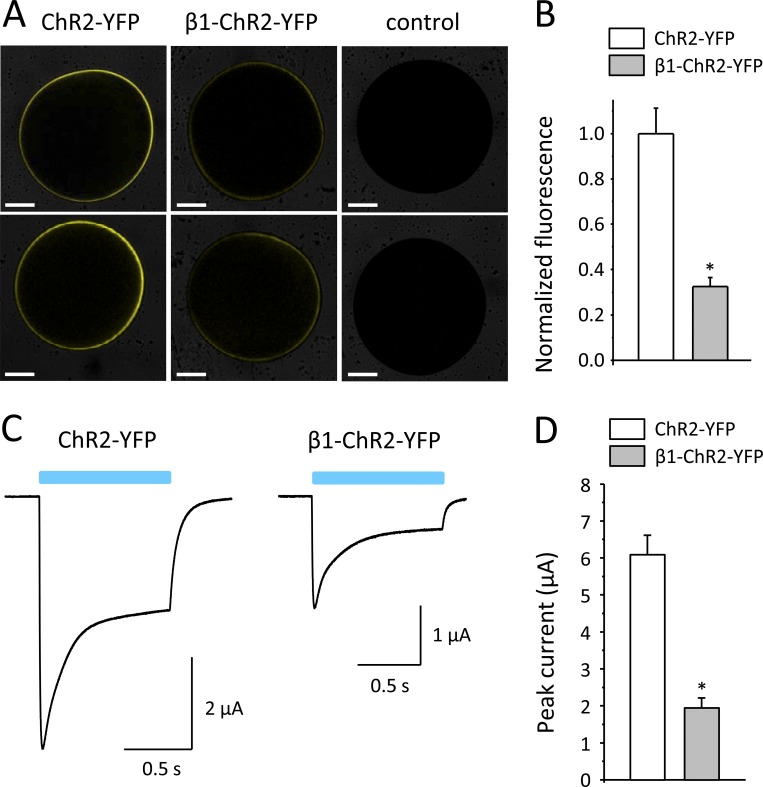

To address the question of whether the observed current reduction was due to a reduced number of β1-ChR2 channels in the plasma membrane, we fused YFP to the C-terminus of β1-ChR2 and measured whole-cell fluorescence intensities using a laser scanning microscope (LSM710). The resulting β1-ChR2-YFP construct also contained a Golgi-to-plasma membrane trafficking signal (Hofherr et al., 2005) and the ER export motif FCYENEV (Stockklausner et al., 2001). Compared with oocytes injected with ChR2-YFP cRNA, fluorescence signals were markedly reduced in oocytes expressing β1-ChR2-YFP (see representative oocytes in Fig. 4 A). Surface fluorescence intensities determined by the implemented ZEN 2010 software were significantly decreased to 32.5% in β1-ChR2-YFP compared with ChR2-YFP (Fig. 4 B). Whole-cell photocurrents recorded in parallel experiments were similarly reduced in β1-ChR2-YFP (31.9% versus ChR2-YFP; see Fig. 4, C and D). Taken together, these data suggest that the number of β1-ChR2 channels was reduced in the plasma membrane and that subcellular processing and trafficking of ChR2 was affected by coupling the Na+ channel β1 subunit. Photocurrents through β1-ChR2-YFP were larger compared with β1-ChR2 (1.94 ± 0.26 µA and 0.65 ± 0.07 µA, respectively; P < 0.05), suggesting that the trafficking and ER export signals in β1-ChR2-YFP enhanced cell surface expression.

Figure 4.

Comparison of membrane fluorescence and photocurrents in Xenopus oocytes expressing ChR2-YFP and β1-ChR2-YFP. (A) Representative fluorescence images of Xenopus oocytes. Noninjected control oocytes showed only faint background fluorescence. Scale bars: 0.25 mm. (B) Normalized fluorescence intensities. Data points are from three different oocyte batches with n = 22 for ChR2-YFP and n = 19 for β1-ChR2-YFP (*, P < 0.05 versus ChR2-YFP). (C) Representative whole-cell currents through ChR2-YFP and β1-ChR2-YFP. (D) Peak current amplitudes. Number of measurements were n = 27 for ChR2-YFP and n = 26 for β1-ChR2-YFP (*, P < 0.05 versus ChR2-YFP). Four different oocyte batches were used. Error bars represent SEM.

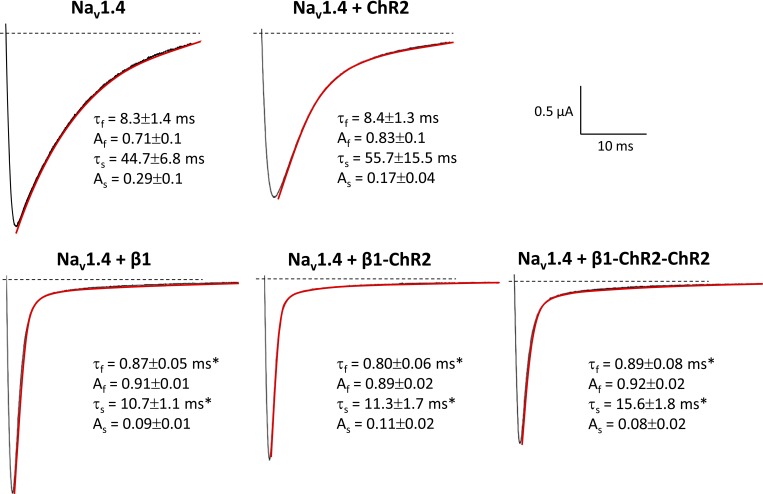

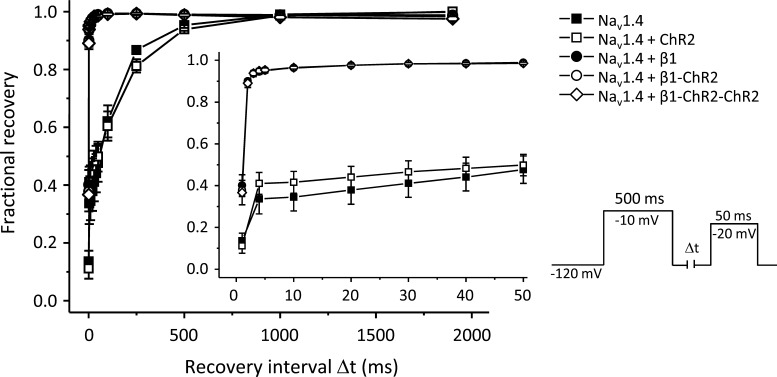

Next, we coexpressed β1-ChR2 with the skeletal muscle isoform Nav1.4 to test for functional interaction with a Na+ channel α subunit. Modulatory effects of β1 can be easily followed by its ability to accelerate inactivation of brain-type and skeletal muscle Na+ channels in Xenopus oocytes (Isom et al., 1992; Wallner et al., 1993; Patton et al., 1994; Chen and Cannon, 1995). In mammalian cell systems, this β1 effect cannot be observed, i.e., expression of α subunits alone is sufficient to record fast-inactivating Na+ currents (Ukomadu et al., 1992; West et al., 1992). As shown in Fig. 5 (red lines), expression of Nav1.4 resulted in the typical slow decay of macroscopic whole-cell currents. When coexpressing β1, inactivation of Nav1.4 was significantly accelerated. Both the fast and slow time constants of inactivation, τf and τs, were significantly shortened (see values in Fig. 5). This specific β1 property was also intrinsic to both β1-ChR2 and β1-ChR2-ChR2, suggesting that ChR2 linkage did not alter important structural and functional β1 features. Moreover, we determined a variety of kinetic parameters of Nav1.4 channels in the absence and presence of one of the three β1 constructs. We found (1) that steady-state activation and inactivation were shifted toward hyperpolarized potentials (Table 1), and (2) that recovery from inactivation was faster when coexpressing either wild type β1 or one of the β1-linked ChR2 variants (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Coexpression of ChR2 alone had no effect on Na+ channel properties (Figs. 5 and 6 and Table 1).

Figure 5.

Representative Nav1.4 current traces at a test potential of −10 mV in Xenopus oocytes. Coexpression of β1 resulted in a faster decay of macroscopic Na+ currents through Nav1.4 channels. To better illustrate the effect on inactivation, we selected whole-cell currents with similar amplitude. Current traces were fitted (red) using a biexponential function: I = Af × exp(−t/τf) + As × exp(−t/τs), where τf and τs are the fast and slow time constants, and Af and As are the corresponding amplitudes. Both fast and slow time constants, τf and τs, were significantly shorter. This well-known β1 property remained preserved in β1-ChR2 and β1-ChR2-ChR2 and was not obtained when coexpressing ChR2 (top). Values for τf, Af, τs, and As are from at least six different measurements (*, significantly different versus Nav1.4, P < 0.05). This typical acceleration of inactivation was also obtained at all other test pulses.

Table 1. Modulation of Nav1.4 channels in Xenopus oocytes by β1, β1-ChR2, and β1-ChR2-ChR2.

| Channel | Steady-state activation | Steady-state inactivation | Recovery from inactivation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vm (mV) | s (mV) | Vh (mV) | s (mV) | τf (ms) | Af | τs (ms) | As | |

| Nav1.4 | −19.8 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | −36.3 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.57 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 153 ± 10.3 | 0.54 ± 0.10 |

| Nav1.4 + ChR2 | −19.7 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | −40.0 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 1.19 ± 0.65 | 0.63 ± 0.10 | 218 ± 3.51 | 0.37 ± 0.10 |

| Nav1.4 + β1 | −24.1 ± 0.8a | 2.9 ± 0.3 | −48.4 ± 4.0a | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.003a | 17.6 ± 4.27a | 0.01 ± 0.003a |

| Nav1.4 + β1-ChR2 | −24.2 ± 1.7a | 2.3 ± 0.4 | −46.0 ± 1.7a | 3.8 ± 0.1a | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.002a | 21.8 ± 2.36a | 0.01 ± 0.002a |

| Nav1.4 + β1-ChR2-ChR2 | −22.8 ± 0.7a | 2.6 ± 0.3 | −46.1 ± 1.0a | 3.8 ± 0.1a | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.99 ± 0.002a | 19.7 ± 5.96a | 0.01 ± 0.002a |

Coexpression of β1 as well as both ChR2-coupled β1 subunits significantly shifted the steady-state activation and inactivation curves toward hyperpolarized potentials. Moreover, the amplitudes of the fast recovery time constant (Af) were increased, and the shorter time constants (τs) as well as the respective amplitudes (As) were clearly reduced, further indicating that coupling of ChR2 did not alter typical features of the β1 subunit. For equations and abbreviations, see Materials and methods.

P < 0.05 versus Nav1.4 (with n = 4–8).

Figure 6.

Acceleration of recovery from inactivation of Nav1.4 by β1, β1-ChR2, and β1-ChR2-ChR2. The respective voltage protocol is shown on the right. During the first pulse (500 ms at −10 mV), Nav1.4 channels were activated; subsequently they accumulated in the inactivated state. During the time interval Δt, channels were allowed to recover at −120 mV. The second test pulse to −20 mV was used to determine the respective fraction of non-inactivated channels. Coexpression of β1 as well as both ChR2-coupled β1 subunits accelerated this recovery process. Data points are from two oocyte batches and four to eight different recordings. For statistics, see Table 1. Error bars represent SEM.

In conclusion, expression of β1-ChR2 and β1-ChR2-ChR2 resulted in both typical ChR2 currents and β1-modulatory effects on Nav1.4. Because we could not observe a difference between the two fusions, we continued with β1-ChR2.

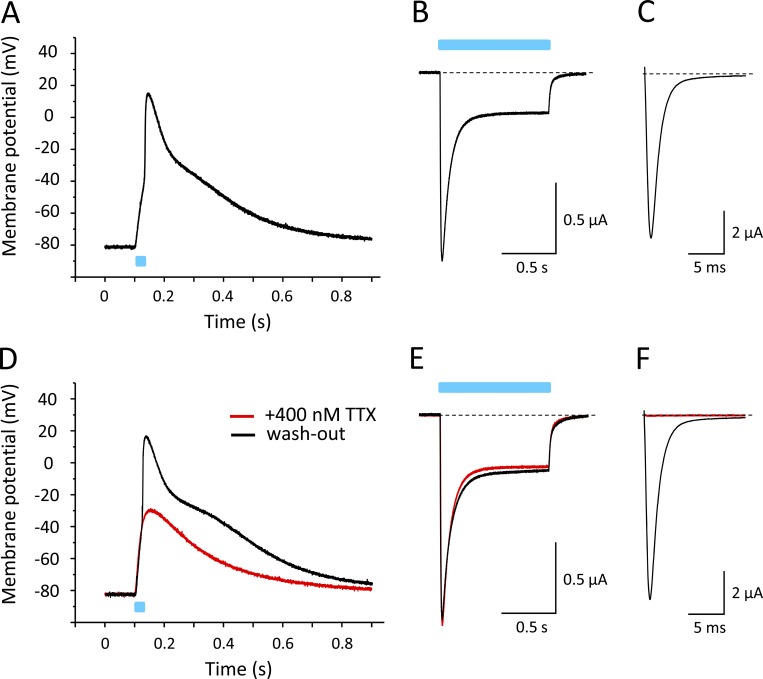

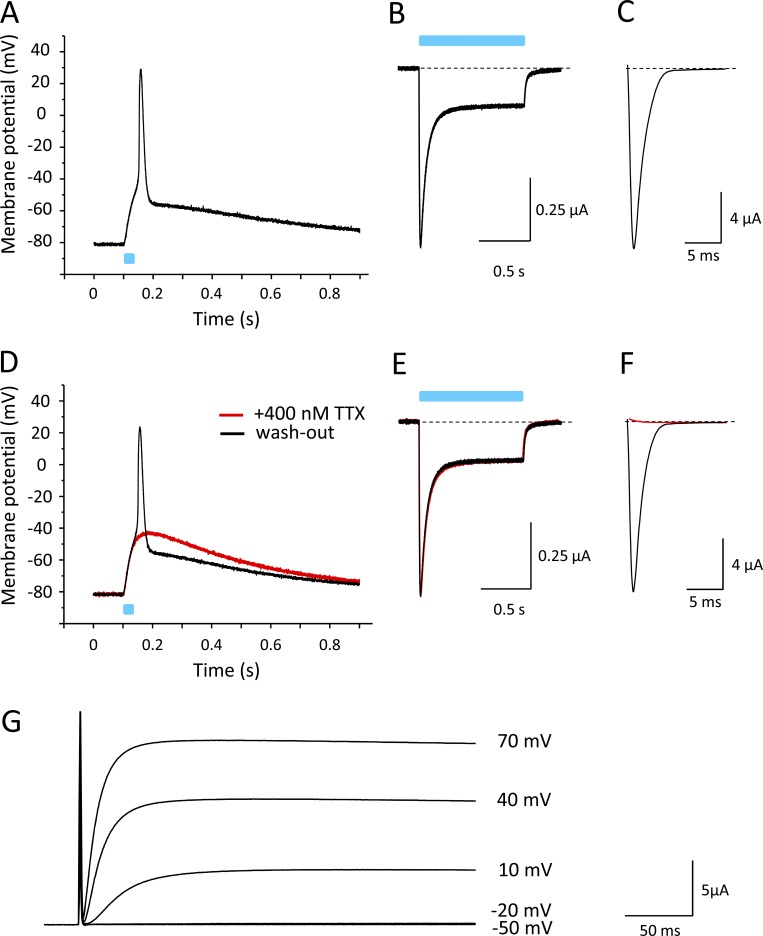

Light-induced APs using the ChR2-linked β1 subunit and Nav1.4

After confirming that ChR2 coupling did not affect modulatory functions of the β1 subunit, we injected oocytes with cRNA for Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 at an equimolar ratio (10 and 2.75 ng per oocyte, respectively). We recorded light-induced voltage changes in the current-clamp mode after an incubation time of 3 d (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7 A, a 25-ms blue-light pulse caused a rapid change of membrane voltage, resembling the steep upstroke of a typical AP of excitable cells. The fast upstroke from −80 mV to nearly +20 mV was followed by a long repolarization phase. Voltage-clamp recordings confirmed the expression of β1-ChR2 and Nav1.4 (Fig. 7, B and C, respectively). To confirm that the rapid depolarization phase was due to Na+ channel activity, we applied 400 nM of the highly specific Na+ channel blocker TTX. As shown in Fig. 7 D, the 25-ms light pulse did not result in an overshoot to positive membrane potentials (red line). Currents through β1-ChR2 were not affected (Fig. 7 E), indicating that the initial depolarization to approximately −35 mV in the presence of TTX was due to ChR2 activity. The following fast upstroke to positive potentials, illustrated in Fig. 7 A, can be clearly attributed to Nav1.4 activity, because the toxin completely blocked voltage-gated Na+ currents at 400 nM (red line in Fig. 7 F). Washout of TTX restored both the light-triggered AP and Nav1.4 currents (black lines in Fig. 7, D and F, respectively).

Figure 7.

Light-induced APs in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2. All recordings shown were performed on a single oocyte. Light pulses are illustrated as blue bars. (A) Current-clamp recording. The membrane potential was set to −80 mV, and the change of membrane voltage was followed on a 25-ms light pulse delivered to the whole oocyte. For AP variability and for detailed statistics, see Fig. S1 and Table S1. (B) Corresponding whole-cell current through β1-ChR2 channels recorded in the voltage-clamp mode. Pulse duration was 1 s. (C) Nav1.4 whole-cell current of the same oocyte recorded in the voltage-clamp mode (holding potential, −120 mV; test pulse, −25 mV). (D) Current-clamp recording in the presence of 400 nM TTX (red). The remaining depolarization was due to ChR2 activity. Washout restored the fast upstroke to nearly +20 mV (black). (E) TTX did not affect β1-ChR2 activity (voltage-clamp recording as in B). (F) Nav1.4 channels were completely blocked in the presence of 400 nM TTX (voltage-clamp mode as in C). Black line shows the Na+ current after washout of TTX.

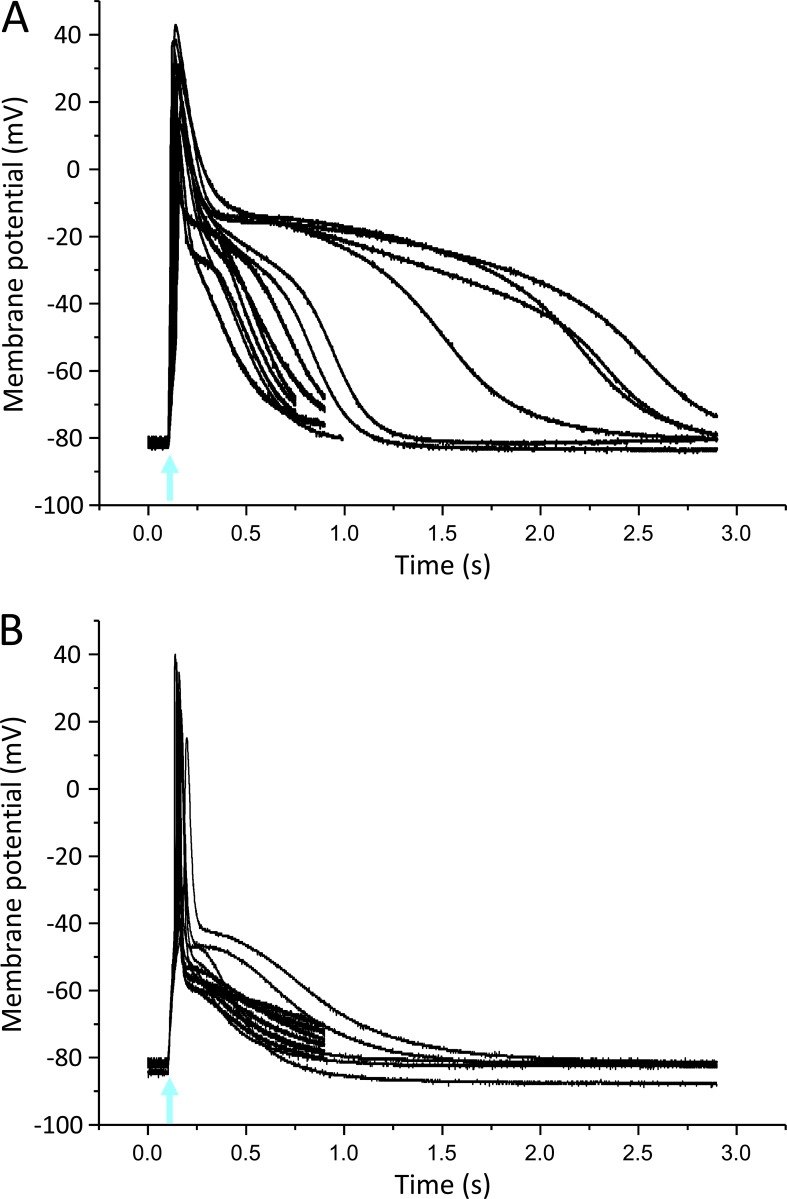

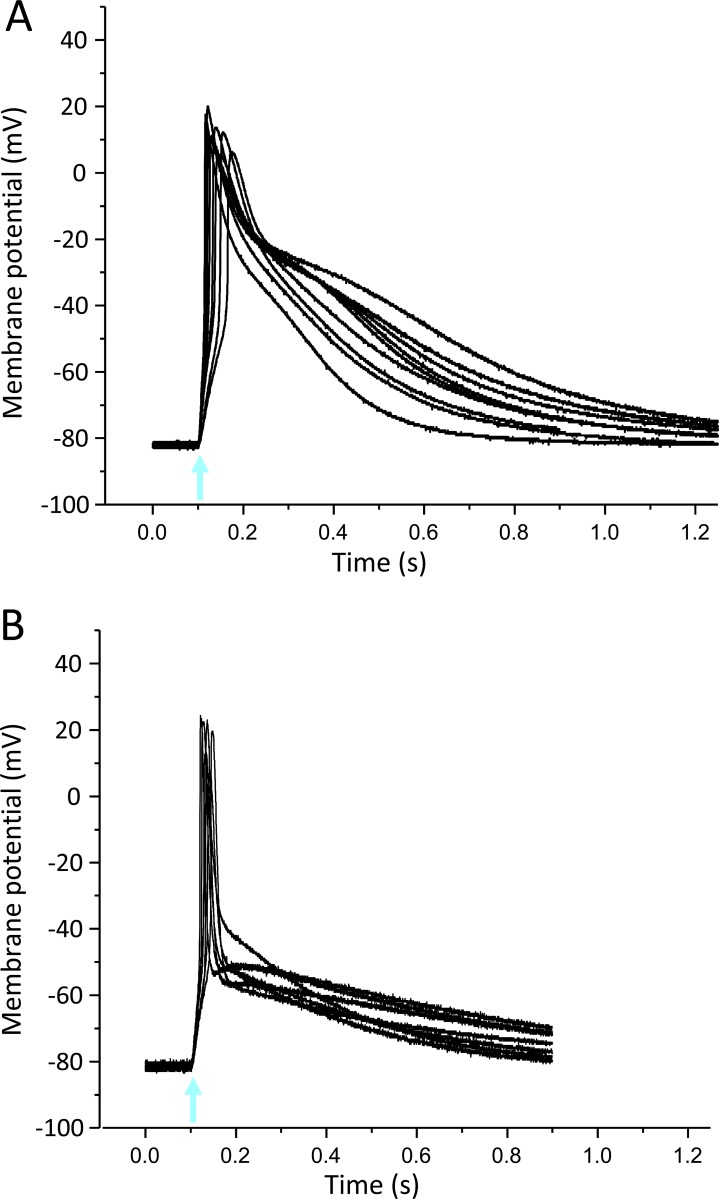

Figure S1.

Light-induced APs in Xenopus oocytes using the skeletal muscle Na+ channel subtype Nav1.4. (A) Thirteen superimposed current-clamp recordings in oocytes expressing Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2. (B) Eleven superimposed current-clamp recordings in oocytes expressing Nav1.4, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1. Coexpression of the voltage-gated K+ channel led to AP shortening and a less pronounced variability in AP duration and shape. For detailed statistics, see Table S1. The blue-light flash is indicated by an arrow.

In Fig. 8 A, the light-induced current was plotted under the AP of another oocyte coexpressing Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2. At a holding potential of −80 mV, the short light pulse caused an inward current through β1-ChR2. Corresponding changes of the membrane voltage toward depolarized potentials should be rapidly corrected by the amplifier, owing to its fast clamp properties. Consequently, Na+ currents through Nav1.4 are not possible when clamping the membrane voltage at −80 mV, and application of 400 nM TTX did not result in a current reduction (Fig. 8 B). At the same time, blocking of Nav1.4 channels did not lead to a reversion of the membrane polarity, similarly as shown in Fig. 7. As further shown in Figs. 7 and 8, repolarization was extremely long. The oocyte membrane remained depolarized usually for >1 s. Voltage-gated Na+ channels are inactivated within a few milliseconds, and currents through β1-ChR2 can at most partially account for a prolonged repolarization, because this channel also rapidly inactivates in the dark (see Fig. 8). Even at a membrane potential of −80 mV, β1-ChR2 currents drop to <5% of the transient current after ∼100 ms, and channels were fully closed or inactivated after ∼300 ms. The long repolarization phase must largely depend on endogenous channels activated during β1-ChR2-/Nav1.4-mediated depolarization, as discussed later.

Figure 8.

Light-induced changes of membrane potential and membrane current upon coexpression of Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Current-clamp and voltage-clamp recording in the absence of TTX. The membrane potential was set to −80 mV, and both the change of membrane voltage and the inward current were followed on a 25-ms light pulse delivered to the whole oocyte. (B) Current-clamp and voltage-clamp recording in the presence of 400 nM TTX (same oocyte as in A). The toxin did not reduce the light-triggered inward current recorded at −80 mV. Pulsing from −120 to −35 mV in the voltage-clamp mode revealed that the toxin blocked >99% of Nav1.4 channels, similarly as shown in Fig. 7.

AP shortening by Kv2.1 coexpression

To facilitate AP repolarization, we coexpressed in addition to Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 the delayed rectifier K+ channel Kv2.1. We assumed that this channel should be activated during the depolarization phase, as similarly observed in native excitable cells. As illustrated for a representative oocyte in Fig. 9 A, the K+ channel clearly accelerated repolarization. Membrane potentials changed from approximately +30 mV to −60 mV within <30 ms. Thus, repolarization in the presence of Kv2.1 occurred similarly as fast as depolarization. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 7, the overshoot of the AP and the inward current through Nav1.4 channels were absent when applying TTX (Fig. 9, D and F, respectively). The toxin had no effect on β1-ChR2 currents (Fig. 9 E). The corresponding K+ currents through Kv2.1 are illustrated in Fig. 9 G.

Figure 9.

Acceleration of AP repolarization by Kv2.1. Recordings were performed on a single oocyte coexpressing Nav1.4, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1. (A) Current-clamp recording (pulse duration 25 ms). For statistics on AP shortening by Kv2.1, see Table S1. (B) Corresponding whole-cell current through β1-ChR2 channels recorded in the voltage-clamp mode (pulse duration 1 s). (C) Nav1.4 whole-cell current of the same oocyte recorded in the voltage-clamp mode (test pulse −25 mV). (D) Current-clamp recording at 400 nM TTX (red). Washout restored the AP (black). (E) Currents through β1-ChR2 in the absence and presence of TTX (pulse duration 1 s). (F) Block of Nav1.4 channels by 400 nM TTX (red). Washout completely restored the voltage-gated Na+ current. (G) Corresponding Kv2.1 current (voltage-clamp mode). Test pulses are indicated. The overlapping Na+ current is not visible due to the presence of 400 nM TTX. The amount of coinjected Kv2.1 cRNA was 50 pg per oocyte. The magnitude of the injected current required to set the initial membrane potential to −80 mV was not altered by Kv2.1 coexpression.

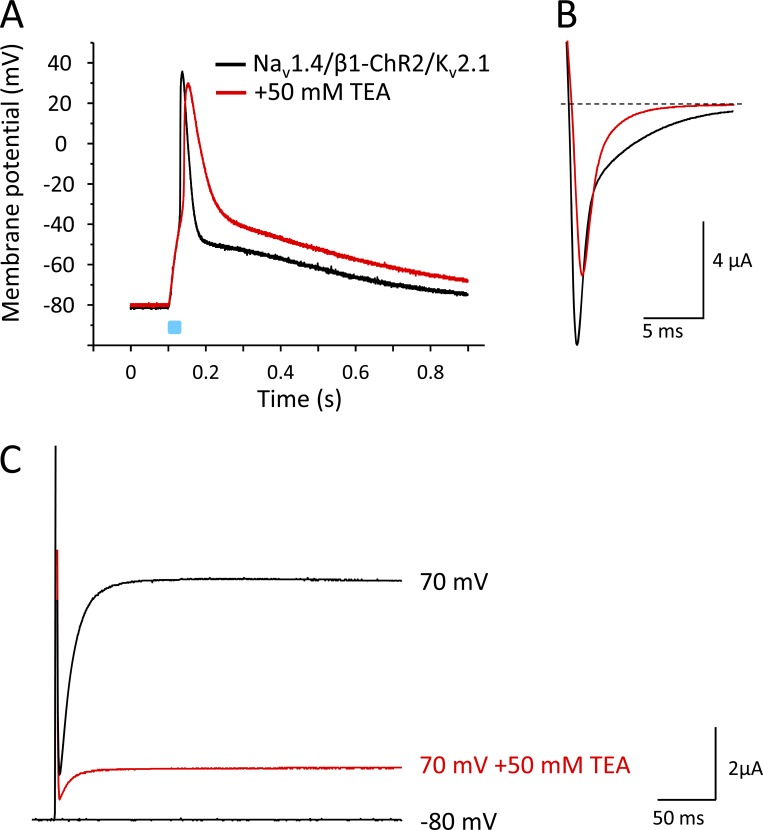

To better illustrate the effect of Kv2.1 on AP repolarization, we applied the nonspecific K+ channel blocker TEA (50 mM; Fig. 10). Using this compound, we noticed two effects. First, repolarization was clearly delayed when >75% of Kv2.1 channels were blocked at this TEA concentration (red lines in Fig. 10, A and C). Second, AP upstroke velocity was slightly reduced, which was due to a partial block of Nav1.4 channels (Fig. 10 B; O’Leary and Horn, 1994). TEA did not affect β1-ChR2 currents (see current data in legend to Fig. 10). Correspondingly, we did not observe an alteration of the early depolarization phase (Fig. 10 A).

Figure 10.

Effect of the nonspecific K+ channel blocker TEA on light-triggered APs in Xenopus oocytes. Recordings were performed on a single oocyte expressing Nav1.4, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1. Duration of the light pulse was 25 ms. (A) Current-clamp recording in the absence and presence of 50 mM TEA. TEA reduced the upstroke velocity, which was due to a partial block of Nav1.4 channels, and caused a deceleration of AP repolarization, which was due to a reduction of the Kv2.1 current. The early depolarization phase to nearly −55 mV remained unchanged, because β1-ChR2 currents were not affected by TEA. Corresponding light-triggered current values were as follows: Ipeak = 581 ± 212 nA, Iplateau = 279 ± 95 nA (without TEA), and Ipeak = 605 ± 224 nA, Iplateau = 307 ± 109 nA (50 mM TEA; P > 0.2 with n = 10). (B) Corresponding Nav1.4 currents. The test pulse was −10 mV. At 50 mM TEA, Nav1.4 was partially blocked (red). (C) Corresponding Kv2.1 currents. At 50 mM TEA, >75% of Kv2.1 channels were blocked, causing the pronounced AP prolongation seen in A.

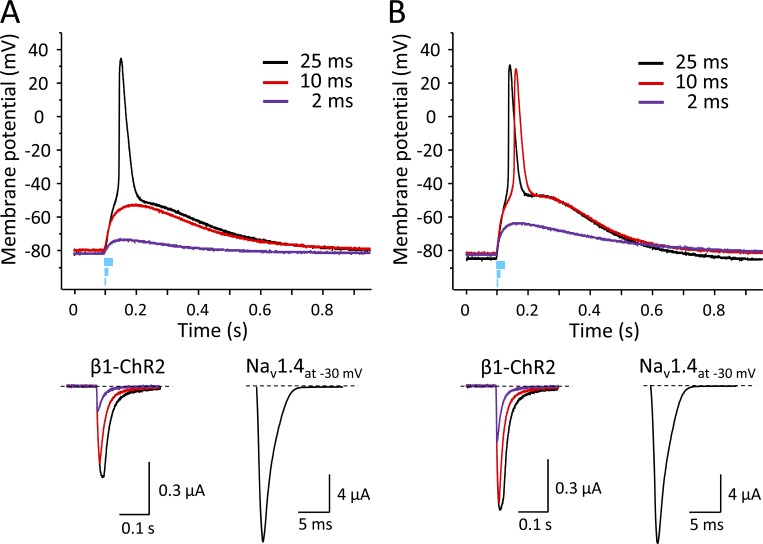

In conclusion, the channel combination Nav1.4/β1-ChR2/Kv2.1 can be used to generate light-induced fast alterations of membrane voltage, strongly resembling typical APs of excitable cells. However, complete repolarization to the resting potential lasted for ∼1 s also in the presence of the delayed rectifier Kv2.1. We therefore applied shorter light pulses to estimate the threshold photocurrent and answer the question of whether the long-lasting post-spike depolarization could be limited when fewer β1-ChR2 channels are activated. Fig. 11 shows the effect of the light pulse duration on both the membrane potential and the corresponding photocurrent for two different oocytes coexpressing Nav1.4, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1 (Fig. 11, A and B). Application of blue light for 25 ms resulted in typical APs in both oocytes (black lines in Fig. 11, A and B, upper part). The corresponding β1-ChR2 currents were 0.51 and 0.70 µA, respectively. In both cases, however, the 2-ms light pulse was not sufficient to trigger APs (purple lines in Fig. 11, A and B, upper part). The corresponding β1-ChR2 currents were 0.14 and 0.31 µA, respectively. The intermediate pulse duration of 10 ms resulted in a differential effect. In one oocyte, the induced photocurrent of 0.44 µA was not sufficient to elicit an AP (red lines in Fig. 11 A). In the second oocyte, the 10-ms flash produced an above-threshold photocurrent of 0.67 µA (red lines in Fig. 11 B). Compared with the corresponding 25-ms pulse, however, the AP upstroke was slightly delayed. In conclusion, APs could be obtained using this batch of oocytes, when the light-induced photocurrent through β1-ChR2 channels and the Nav1.4 currents were ≥0.51 and 16.6 µA, respectively. Both conditions are fulfilled at 25 ms in Fig. 11 A as well as at 10 ms in Fig. 11 B. Moreover, the shorter light pulse of 10 ms did not substantially affect the long-lasting cell depolarization phase, independently of whether an AP was induced (compare red and black lines in Fig. 11, A and B).

Figure 11.

Effect of light pulse duration in two different oocytes coexpressing Nav1.4, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1 on the membrane potential and on the corresponding photocurrent. Duration of the light flashes was 25, 10, and 2 ms. Amounts of coinjected cRNA per oocyte were 10 ng Nav1.4, 2.75 ng β1-ChR2, and 50 pg Kv2.1. (A) The 25-ms pulse induced a peak photocurrent of 0.51 µA, which led to successful AP triggering in this oocyte (black line). In contrast, 10 and 2 ms were too short to activate a sufficient number of β1-ChR2 channels, so the threshold potential was not achieved (red and purple lines, respectively). Light-induced peak currents were 0.44 and 0.14 µA, respectively. (B) Blue-light pulses induced larger photocurrents, indicating a higher β1-ChR2 expression level. The 25-ms pulse resulted in a peak photocurrent of 0.70 µA and produced a typical AP (black). The short 2-ms pulse was not sufficient to elicit an AP. The corresponding light-induced current of 0.31 µA was larger than in A, and consequently, the subthreshold depolarization was more pronounced (compare purple curves in upper graphs in A and B). Application of an intermediate pulse (10 ms, red) resulted in a peak photocurrent of 0.67 µA, and in above-threshold activation. However, depolarization was delayed compared with the longer light pulse of 25 ms. In both oocytes, the membrane resistance as well as the Nav1.4 current at −30 mV were very similar (0.59 MΩ and 16.6 µA in A and 0.5 MΩ and 16.9 µA in B, respectively). K+ currents at +70 mV were 6.4 µA (A) and 8.0 µA (B).

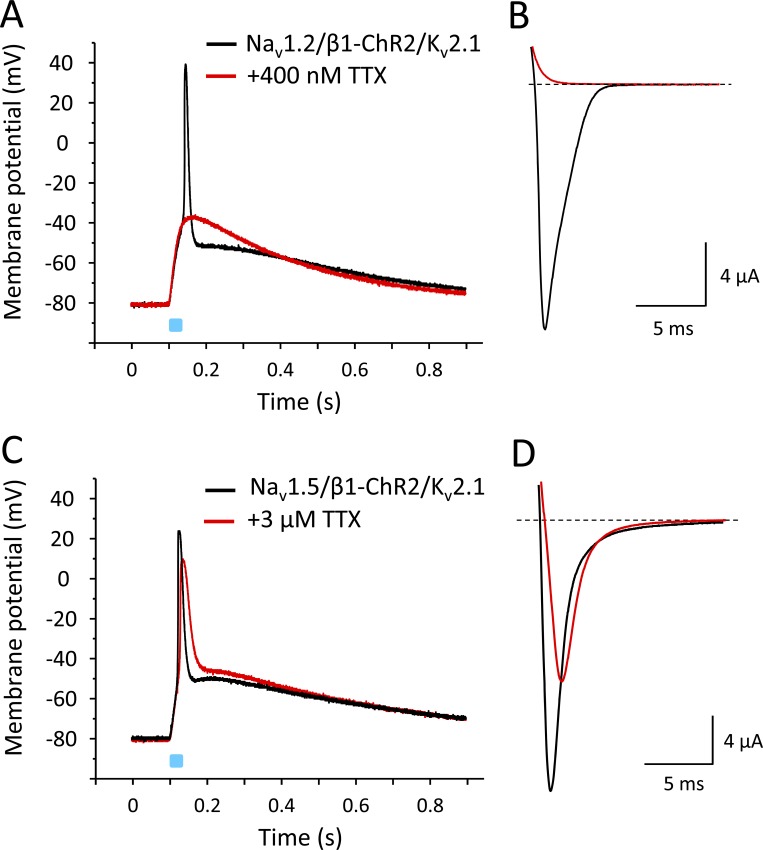

Light-induced APs using brain- and heart-type Na+ channels

Because the β1 subunit is widely expressed in excitable tissues and interacts with various Na+ channels, we tested whether APs can be also triggered when coexpressing neuronal Nav1.2 and cardiac Nav1.5 channels with β1-ChR2. To facilitate repolarization, we also coinjected cRNA for Kv2.1. As shown in Fig. 12, both Na+ channels caused a fast alteration of the membrane potential, similarly as observed for the skeletal muscle isoform Nav1.4. In case of neuronal Nav1.2, application of 400 nM TTX completely blocked the Na+ inward current, and consequently, also the light-induced overshoot to positive potentials (Fig. 12, A and B). In contrast to Nav1.2, the cardiac Na+ channel Nav1.5 belongs to the TTX-resistant Na+ channels, with reported IC50 values ≤6 µM (Goldin, 2001). Application of 3 µM TTX blocked <50% of Nav1.5 channels (Fig. 12 D). The remaining channels were sufficient to trigger an AP-like alteration of the membrane potential. At the same time, we noticed a reduced AP upstroke velocity and amplitude.

Figure 12.

Light-induced APs in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing β1-ChR2 and Kv2.1 with either Nav1.2 or Nav1.5. (A and C) Current-clamp recordings. For detailed statistics on the effect of Kv2.1 on Nav1.5-mediated APs, see Fig. S2 and Table S2. (B and D) Corresponding Na+ currents in the absence and presence of TTX. Similarly to Nav1.4, neuronal Nav1.2 channels belong to the TTX-sensitive Na+ channels; they can be blocked at nanomolar TTX concentrations. Cardiac Nav1.5 channels are TTX resistant, with IC50 values >1 µM. The peak and plateau currents through β1-ChR2 were Ipeak = 768 nA, Iplateau = 193 nA (Nav1.2-expressing cell in A and B), and Ipeak = 957 nA, Iplateau = 193 nA (Nav1.5-expressing cell in C and D). The K+ currents through Kv2.1 were I+70 mV = 14.3 µA (Nav1.2-expressing cell, A and B), and I+70 mV = 30.9 µA (Nav1.5-expressing cell, C and D). Duration of the light pulse was 25 ms.

Figure S2.

Light-induced APs in Xenopus oocytes using the cardiac Na+ channel Nav1.5. (A) Nine superimposed current-clamp recordings in oocytes expressing Nav1.5 and β1-ChR2. (B) Seven superimposed current-clamp recordings in oocytes expressing Nav1.5, β1-ChR2, and Kv2.1. Similarly, as observed for Nav1.4-injected oocytes, coexpression of Kv2.1 led to a pronounced AP shortening. For detailed statistics, see Table S2. The blue-light flash is indicated by an arrow.

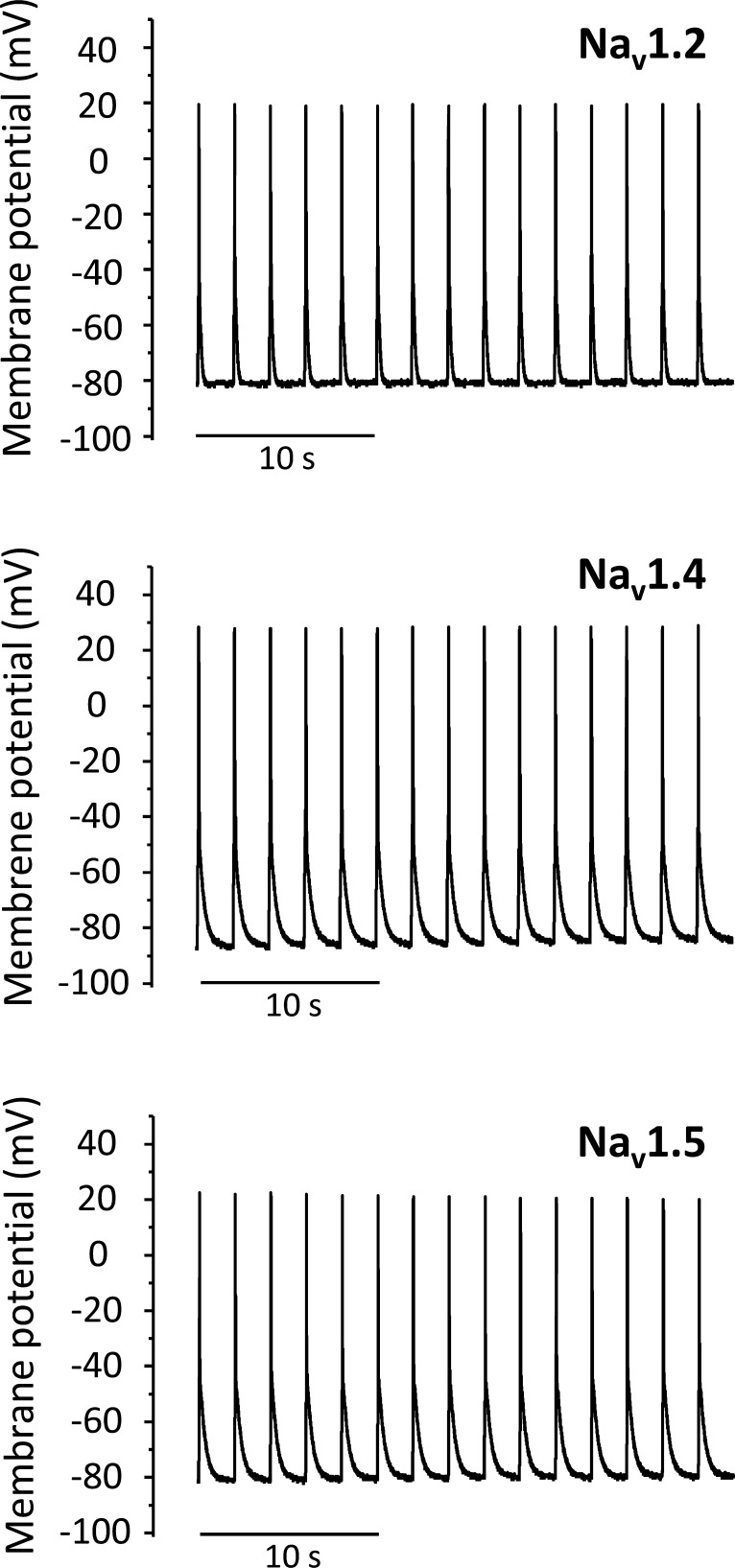

Finally, we tested whether APs can be obtained repetitively. We applied 50-ms light pulses every 2 s to whole oocytes coexpressing Nav1.2, Nav1.4, or Nav1.5 with β1-ChR2 and Kv2.1. Fig. 13 illustrates that AP firing at 0.5 Hz could be triggered with all three Na+ channel subtypes.

Figure 13.

Repetitive firing of light-triggered APs in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing either neuronal Nav1.2, skeletal muscle Nav1.4, or cardiac Nav1.5 with β1-ChR2 and Kv2.1. The membrane potential was set to −80 mV (Nav1.2 or Nav1.5) or −85 mV (Nav1.4), and the change of membrane voltage was followed in the current-clamp mode on 50-ms light pulses every 2 s.

Discussion

In the present study, we provide a novel optogenetic tool to switch naturally nonexcitable cells into excitable cells and to study the shape of APs. Using a fusion construct consisting of ChR2 and the common β1 subunit of voltage-gated Na+ channels, we were able to elicit APs in Xenopus oocytes expressing neuronal, skeletal muscle, or cardiac voltage-gated Na+ channels.

Recently, Corbin-Leftwich et al. also recorded APs in the same expression system using a set of ion channels, including Nav1.4/β1 and non–voltage-gated and voltage-gated K+ channels (Corbin-Leftwich et al., 2016, 2018). In contrast to our study, the authors adapted the voltage-clamping circuits of a traditional two-electrode voltage-clamp setup, so that fast changes of membrane voltage became visible (“loose-clamp” mode). Besides current injection and light activation, there are more possibilities to elicit APs. Shapiro et al. (2012) discovered the optocapacitance mechanism, in which infrared radiation increases membrane temperature and its capacitance. The capacitor discharge leads to a current that is sufficient to generate APs (Shapiro et al., 2012; Carvalho-de-Souza et al., 2018). Furthermore, other studies have shown the transformation of nonexcitable HEK293 cells into spontaneously firing cells by overexpressing voltage-gated Na+ channels and inward rectifier K+ channels (Park et al., 2013; McNamara et al., 2016; Ling et al., 2018). Moreover, coexpression of the channelrhodopsin variant CheRiff in these spiking HEK293 cells even allowed for blue-light controlled AP firing (Hochbaum et al., 2014; McNamara et al., 2016).

We have chosen the major β subunit of voltage-gated Na+ channels for an optogenetic AP firing because of the following reasons. First, the β1 subunit interacts with various voltage-gated Na+ channels. Consequently, β1-ChR2 fusions could be used as optical switches for several Na+ channel isoforms in different excitable tissues. Second, neuronal, skeletal muscle, and cardiac Na+ channels even require coexpression of β1 for normal channel gating. Consequently, coexpression of β1-coupled ChR2 channels in normally nonexcitable cells should result in native Na+ currents and in an AP upstroke velocity more closely resembling the in vivo situation. For example, the shift of steady-state activation toward hyperpolarized potentials should facilitate AP spiking, thereby compensating for a lower expression of β1-ChR2.

There are several potential applications for this novel optogenetic tool. First, one could address basic questions regarding the effect of individual ion fluxes on AP shape, similarly as reported recently (Corbin-Leftwich et al., 2018). For example, it seems to be promising to include naturally occurring mutations causing life-threatening channelopathies such as epilepsy, Brugada syndrome, sick sinus syndrome, or long QT syndrome (Webster and Berul, 2013). Hundreds of monogenetic long QT syndrome variations are known to cause electrocardiogram alterations and sudden cardiac death (Zimmer and Surber, 2008; Bohnen et al., 2017), but very limited data are available regarding the actual impact of a given point mutation on AP shape. The challenging possibility to specifically design APs could be the basis for a second application, a drug screening of host cells expressing wild type or mutant channels associated with epilepsy or cardiac events. It would be conceivable, and should be possible, even to develop respective high-throughput systems with blue LEDs. Third, β1-ChR2 could be expressed not only in heterologous cells such as Xenopus oocytes or HEK293 cells, but also in neurons, cardiomyocytes, or other mammalian cells, either using suitable in vitro transfection methods or transgenic animal technologies. It is possible that, in contrast to wild type ChR2, β1-ChR2 will preferentially localize at cellular spots with a high density of native Na+ channels so that light-induced APs originate more specifically at the physiological site, such as the axon hillock or the intercalated disc region.

Despite our enthusiasm, we have to be sensitive to all the present limitations. First of all, our β1-ChR2 construct seems not to be optimal, considering the reduction in surface expression and light-induced ChR2 currents (see Figs. 3 and 4). Surprisingly, coupling a second ChR2 did not help, suggesting either that one of the ChR2 channel domains in β1-ChR2-ChR2 is inactive, or that intracellular processing is less efficient and/or that degradation is enhanced. Interestingly, we recorded larger photocurrents in β1-ChR2-YFP compared with β1-ChR2 (Figs. 3 B and 4 D). The reason for a higher expression level of the YFP-coupled variant is actually unknown. We suggest that incorporation of established trafficking and ER export signals (Stockklausner et al., 2001; Hofherr et al., 2005), which are present in β1-ChR2-YFP, are a first promising option to improve β1-ChR2 and β1-ChR2-ChR2. Second, ChR2 also conducts Ca2+, which might in turn affect intracellular pathways or endogenous ion channels of the host cell. Future studies using Ca2+-free solution or ChR2 mutants with a reduced Ca2+ conductance (Cho et al., 2019) may eliminate or reduce possible secondary Ca2+ effects. Third, to elicit an AP, three major conditions must be met: (1) a sufficient photocurrent, (2) a high density of Na+ channels, and (3) a high resistance of the oocyte membrane. If one of those parameters is suboptimal, others could compensate. For example, even equimolar Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 cRNA ratios did not result in constant Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 current ratios, and APs could be triggered at lower Na+ and higher ChR2 currents and vice versa (see Table S1 and Table S2). Future studies with defined TTX concentrations and varying light intensities could be helpful to adjust a constant Na+ to β1-ChR2 channel ratio, so that AP initiation can be more exactly controlled. Currently, we can adjust cRNA ratios, define a cutoff for the membrane resistance (see Materials and methods), and show AP variability and statistics on threshold, overshoot, rise time, and duration (see Table S1 and Table S2). However, it is difficult to exactly control the size of voltage- and light-activated currents as well as the membrane resistance.

Fourth, Xenopus oocytes express a variety of endogenous channels activated by depolarization, hyperpolarization, mechanical stress, and various chemicals or ligands (Weber, 1999; Terhag et al., 2010). The pronounced repolarization phase observed upon Nav1.4/β1-ChR2 coexpression (Figs. 7 and 8) should be largely the result of an endogenous current ensemble. This assumption is supported by our observation that the shape and duration of the repolarization phase varied between the oocyte batches. Moreover, when comparing the time scale of the long-lasting repolarization with the light-induced inward current (Fig. 8 A), it can be suggested that direct depolarizing effects of Nav1.4 and β1-ChR2 on this later AP phase are negligibly low. Candidates contributing to a delayed cell repolarization are voltage-dependent Ca2+ and Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (Barish, 1983; Weber, 1999; Caldwell et al., 2008; Terhag et al., 2010; Corbin-Leftwich et al., 2018). Both may counteract the simultaneous K+ outward flux. Corbin-Leftwich et al. (2018) discussed the impact of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in oocytes and showed that a reduced external Cl− concentration prolongs the repolarization phase. Caldwell et al. (2008) used this endogenous current to monitor the intracellular Ca2+ level to show that mGluR7 signaling is potentiated by a physiological Ca2+ concentration. Currently, this long repolarization is the major limiting factor for repetitive AP firing. Even when coexpressing Kv2.1, we rarely obtained frequencies >0.5 Hz (see Fig. 13). This delayed rectifier K+ channel caused a rapid repolarization up to −55 mV (Figs. 9, 10, 11, and 12). However, full recovery of voltage-gated Na+ channels cannot be achieved at such membrane potentials (see values for steady-state inactivation in Table 1). Our ongoing research with other K+ channel subtypes and measurements in Ca2+-free solutions may further accelerate the AP downstroke, leading to higher AP frequencies. Moreover, it is not unlikely that membrane repolarization is significantly faster when expressing β1-ChR2 in cardiomyocytes or neurons.

In conclusion, β1-ChR2 in combination with a voltage-gated K+ channel is a useful tool to generate light-induced APs with a variety of voltage-gated Na+ channels in naturally unexcitable cells. We are optimistic that current limitations can be overcome and that the new β1-ChR2 fusion construct can promote research in optogenetics.

Supplementary Material

shows statistics on AP parameters for oocytes expressing either Nav1.4/β1-ChR2 or Nav1.4/β1-ChR2/Kv2.1 channels.

shows statistics on AP parameters for oocytes expressing either Nav1.5/β1-ChR2 or Nav1.5/β1-ChR2/Kv2.1 channels.

Acknowledgments

Eduardo Ríos served as editor.

We thank K. Schoknecht, G. Ditze, G. Sammler, P. Hachenburg, C. Ranke, and S. Bernhardt for excellent technical assistance.

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Projektnummer 374031971–TRR 240/A04, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant NA 207/10-1 to G. Nagel.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: F. Walther, D. Feind, C. vom Dahl, and C.E. Müller carried out electrophysiological measurements. T. Kukaj and C. vom Dahl performed fluorescence imaging experiments. T. Zimmer and S. Gao engineered the DNA constructs. T. Zimmer and G. Nagel planned the project. F. Walther, D. Feind, C. vom Dahl, C. Sattler, and T. Zimmer designed the experiments. F. Walther, D. Feind, C. vom Dahl, C. Sattler, and T. Zimmer analyzed the data. C. vom Dahl and T. Zimmer prepared the figures. T. Zimmer, C. vom Dahl, and G. Nagel wrote the manuscript.

References

- Auld V.J., Goldin A.L., Krafte D.S., Marshall J., Dunn J.M., Catterall W.A., Lester H.A., Davidson N., and Dunn R.J.. 1988. A rat brain Na+ channel alpha subunit with novel gating properties. Neuron. 1:449–461. 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90176-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish M.E. 1983. A transient calcium-dependent chloride current in the immature Xenopus oocyte. J. Physiol. 342:309–325. 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A., Schoenenberger P., Mattis J., Tye K.M., Deisseroth K., Hegemann P., and Oertner T.G.. 2011. High-efficiency channelrhodopsins for fast neuronal stimulation at low light levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:7595–7600. 10.1073/pnas.1017210108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. 1987. Single sodium channels from the squid giant axon. Biophys. J. 52:1087–1090. 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83304-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi A., Cui J., Ma Y.P., Olshevskaya E., Pu M., Dizhoor A.M., and Pan Z.H.. 2006. Ectopic expression of a microbial-type rhodopsin restores visual responses in mice with photoreceptor degeneration. Neuron. 50:23–33. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen M.S., Peng G., Robey S.H., Terrenoire C., Iyer V., Sampson K.J., and Kass R.S.. 2017. Molecular Pathophysiology of Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Physiol. Rev. 97:89–134. 10.1152/physrev.00008.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden E.S., Zhang F., Bamberg E., Nagel G., and Deisseroth K.. 2005. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8:1263–1268. 10.1038/nn1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury W.J., and Isom L.L.. 2011. Na Channel β Subunits: Overachievers of the Ion Channel Family. Front. Pharmacol. 2:53 10.3389/fphar.2011.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J.H., Herin G.A., Nagel G., Bamberg E., Scheschonka A., and Betz H.. 2008. Increases in intracellular calcium triggered by channelrhodopsin-2 potentiate the response of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR7. J. Biol. Chem. 283:24300–24307. 10.1074/jbc.M802593200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-de-Souza J.L., Pinto B.I., Pepperberg D.R., and Bezanilla F.. 2018. Optocapacitive Generation of Action Potentials by Microsecond Laser Pulses of Nanojoule Energy. Biophys. J. 114:283–288. 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W.A. 2017. Forty Years of Sodium Channels: Structure, Function, Pharmacology, and Epilepsy. Neurochem. Res. 42:2495–2504. 10.1007/s11064-017-2314-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., and Cannon S.C.. 1995. Modulation of Na+ channel inactivation by the beta 1 subunit: a deletion analysis. Pflugers Arch. 431:186–195. 10.1007/BF00410190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.K., Park D., Yang A., Chen F., Chuong A.S., Klapoetke N.C., and Boyden E.S.. 2019. Multidimensional screening yields channelrhodopsin variants having improved photocurrent and order-of-magnitude reductions in calcium and proton currents. J. Biol. Chem. 294:3806–3821. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin-Leftwich A., Mossadeq S.M., Ha J., Ruchala I., Le A.H., and Villalba-Galea C.A.. 2016. Retigabine holds KV7 channels open and stabilizes the resting potential. J. Gen. Physiol. 147:229–241. 10.1085/jgp.201511517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin-Leftwich A., Small H.E., Robinson H.H., Villalba-Galea C.A., and Boland L.M.. 2018. A Xenopus oocyte model system to study action potentials. J. Gen. Physiol. 150:1583–1593. 10.1085/jgp.201812146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K., and Hegemann P.. 2017. The form and function of channelrhodopsin. Science. 357:eaan5544 10.1126/science.aan5544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldbauer K., Zimmermann D., Pintschovius V., Spitz J., Bamann C., and Bamberg E.. 2009. Channelrhodopsin-2 is a leaky proton pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:12317–12322. 10.1073/pnas.0905852106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellens M.E., George A.L. Jr., Chen L.Q., Chahine M., Horn R., Barchi R.L., and Kallen R.G.. 1992. Primary structure and functional expression of the human cardiac tetrodotoxin-insensitive voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:554–558. 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A.L. 2001. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63:871–894. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A.L., Barchi R.L., Caldwell J.H., Hofmann F., Howe J.R., Hunter J.C., Kallen R.G., Mandel G., Meisler M.H., Netter Y.B., et al. 2000. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 28:365–368. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00116-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gütter C., Benndorf K., and Zimmer T.. 2013. Characterization of N-terminally mutated cardiac Na(+) channels associated with long QT syndrome 3 and Brugada syndrome. Front. Physiol. 4:153 10.3389/fphys.2013.00153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum D.R., Zhao Y., Farhi S.L., Klapoetke N., Werley C.A., Kapoor V., Zou P., Kralj J.M., Maclaurin D., Smedemark-Margulies N., et al. 2014. All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods. 11:825–833. 10.1038/nmeth.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofherr A., Fakler B., and Klöcker N.. 2005. Selective Golgi export of Kir2.1 controls the stoichiometry of functional Kir2.x channel heteromers. J. Cell Sci. 118:1935–1943. 10.1242/jcs.02322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T., Kakuda M., Araki R., and Yawo H.. 2006. Kinetic evaluation of photosensitivity in genetically engineered neurons expressing green algae light-gated channels. Neurosci. Res. 54:85–94. 10.1016/j.neures.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom L.L., De Jongh K.S., Patton D.E., Reber B.F., Offord J., Charbonneau H., Walsh K., Goldin A.L., and Catterall W.A.. 1992. Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 256:839–842. 10.1126/science.1375395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinlogel S., Terpitz U., Legrum B., Gökbuget D., Boyden E.S., Bamann C., Wood P.G., and Bamberg E.. 2011. A gene-fusion strategy for stoichiometric and co-localized expression of light-gated membrane proteins. Nat. Methods. 8:1083–1088. 10.1038/nmeth.1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmann R., Scholle A., Ludwig J., Leicher T., Zimmer T., Pongs O., and Benndorf K.. 2001. Role of the S2 and S3 segment in determining the activation kinetics in Kv2.1 channels. J. Membr. Biol. 182:49–59. 10.1007/s00232-001-0029-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Gutierrez D.V., Hanson M.G., Han J., Mark M.D., Chiel H., Hegemann P., Landmesser L.T., and Herlitze S.. 2005. Fast noninvasive activation and inhibition of neural and network activity by vertebrate rhodopsin and green algae channelrhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:17816–17821. 10.1073/pnas.0509030102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling T., Boyle K.C., Goetz G., Zhou P., Quan Y., Alfonso F.S., Huang T.W., and Palanker D.. 2018. Full-field interferometric imaging of propagating action potentials. Light Sci. Appl. 7:107 10.1038/s41377-018-0107-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara H.M., Zhang H.K., Werley C.A., and Cohen A.E.. 2016. Optically Controlled Oscillators in an Engineered Bioelectric Tissue. Phys. Rev. X. 6:031001. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G., Brauner M., Liewald J.F., Adeishvili N., Bamberg E., and Gottschalk A.. 2005. Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Curr. Biol. 15:2279–2284. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G., Ollig D., Fuhrmann M., Kateriya S., Musti A.M., Bamberg E., and Hegemann P.. 2002. Channelrhodopsin-1: a light-gated proton channel in green algae. Science. 296:2395–2398. 10.1126/science.1072068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G., Szellas T., Huhn W., Kateriya S., Adeishvili N., Berthold P., Ollig D., Hegemann P., and Bamberg E.. 2003. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13940–13945. 10.1073/pnas.1936192100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss H.B., Chiamvimonvat N., Pérez-García M.T., Tomaselli G.F., and Marbán E.. 1995. Functional association of the beta 1 subunit with human cardiac (hH1) and rat skeletal muscle (mu 1) sodium channel alpha subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 106:1171–1191. 10.1085/jgp.106.6.1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary M.E., and Horn R.. 1994. Internal block of human heart sodium channels by symmetrical tetra-alkylammoniums. J. Gen. Physiol. 104:507–522. 10.1085/jgp.104.3.507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Werley C.A., Venkatachalam V., Kralj J.M., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G., and Cohen A.E.. 2013. Screening fluorescent voltage indicators with spontaneously spiking HEK cells. PLoS One. 8:e85221 10.1371/journal.pone.0085221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D.E., Isom L.L., Catterall W.A., and Goldin A.L.. 1994. The adult rat brain beta 1 subunit modifies activation and inactivation gating of multiple sodium channel alpha subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 269:17649–17655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F., Grimm C., and Hegemann P.. 2015. Biophysics of Channelrhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 44:167–186. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M.G., Homma K., Villarreal S., Richter C.P., and Bezanilla F.. 2012. Infrared light excites cells by changing their electrical capacitance. Nat. Commun. 3:736 10.1038/ncomms1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigworth F.J., and Neher E.. 1980. Single Na+ channel currents observed in cultured rat muscle cells. Nature. 287:447–449. 10.1038/287447a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockklausner C., Ludwig J., Ruppersberg J.P., and Klöcker N.. 2001. A sequence motif responsible for ER export and surface expression of Kir2.0 inward rectifier K(+) channels. FEBS Lett. 493:129–133. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02286-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutkowski E.M., and Catterall W.A.. 1990. Beta 1 subunits of sodium channels. Studies with subunit-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 265:12393–12399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhag J., Cavara N.A., and Hollmann M.. 2010. Cave Canalem: how endogenous ion channels may interfere with heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes. Methods. 51:66–74. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukomadu C., Zhou J., Sigworth F.J., and Agnew W.S.. 1992. muI Na+ channels expressed transiently in human embryonic kidney cells: biochemical and biophysical properties. Neuron. 8:663–676. 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90088-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich S., Gueta R., and Nagel G.. 2013. Degradation of channelopsin-2 in the absence of retinal and degradation resistance in certain mutants. Biol. Chem. 394:271–280. 10.1515/hsz-2012-0256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov O., Kovalev K., Polovinkin V., Borshchevskiy V., Bamann C., Astashkin R., Marin E., Popov A., Balandin T., Willbold D., et al. 2017. Structural insights into ion conduction by channelrhodopsin 2. Science. 358:eaan8862 10.1126/science.aan8862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M., Weigl L., Meera P., and Lotan I.. 1993. Modulation of the skeletal muscle sodium channel alpha-subunit by the beta 1-subunit. FEBS Lett. 336:535–539. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80871-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walzik S., Schroeter A., Benndorf K., and Zimmer T.. 2011. Alternative splicing of the cardiac sodium channel creates multiple variants of mutant T1620K channels. PLoS One. 6:e19188 10.1371/journal.pone.0019188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber W.M. 1999. Endogenous ion channels in oocytes of xenopus laevis: recent developments. J. Membr. Biol. 170:1–12. 10.1007/s002329900532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster G., and Berul C.I.. 2013. An update on channelopathies: from mechanisms to management. Circulation. 127:126–140. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J.W., Scheuer T., Maechler L., and Catterall W.A.. 1992. Efficient expression of rat brain type IIA Na+ channel alpha subunits in a somatic cell line. Neuron. 8:59–70. 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90108-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer T., and Benndorf K.. 2002. The human heart and rat brain IIA Na+ channels interact with different molecular regions of the beta1 subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:887–895. 10.1085/jgp.20028703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer T., and Benndorf K.. 2007. The intracellular domain of the beta 2 subunit modulates the gating of cardiac Na v 1.5 channels. Biophys. J. 92:3885–3892. 10.1529/biophysj.106.098889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer T., and Surber R.. 2008. SCN5A channelopathies--an update on mutations and mechanisms. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 98:120–136. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

shows statistics on AP parameters for oocytes expressing either Nav1.4/β1-ChR2 or Nav1.4/β1-ChR2/Kv2.1 channels.

shows statistics on AP parameters for oocytes expressing either Nav1.5/β1-ChR2 or Nav1.5/β1-ChR2/Kv2.1 channels.