TRPM2 cation channels are activated by ADP ribose (ADPR), which binds to two distinct locations in the N- and C-terminal cytosolic domains. Tóth et al. selectively determine the ligand-binding affinities of these two binding sites in sea anemone TRPM2 and provide insights into the mechanistic contributions of several amino acids within the N-terminal site.

Abstract

Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) is a homotetrameric Ca2+-permeable cation channel important for the immune response, body temperature regulation, and insulin secretion, and is activated by cytosolic Ca2+ and ADP ribose (ADPR). ADPR binds to two distinct locations, formed by large N- and C-terminal cytosolic domains, respectively, of the channel protein. In invertebrate TRPM2 channels, the C-terminal site is not required for channel activity but acts as an active ADPR phosphohydrolase that cleaves the activating ligand. In vertebrate TRPM2 channels, the C-terminal site is catalytically inactive but cooperates with the N-terminal site in channel activation. The precise functional contributions to channel gating and the nucleotide selectivities of the two sites in various species have not yet been deciphered. For TRPM2 of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis (nvTRPM2), catalytic activity is solely attributable to the C-terminal site. Here, we show that nvTRPM2 channel gating properties remain unaltered upon deletion of the C-terminal domain, indicating that the N-terminal site is single-handedly responsible for channel gating. Exploiting such functional independence of the N- and C-terminal sites, we selectively measure their affinity profiles for a series of ADPR analogues, as reflected by apparent affinities for channel activation and catalysis, respectively. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we confirm that the same N-terminal site observed in vertebrate TRPM2 channels was already present in ancient cnidarians. Finally, by characterizing the functional effects of six amino acid side chain truncations in the N-terminal site, we provide first insights into the mechanistic contributions of those side chains to TRPM2 channel gating.

Introduction

Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) is a member of the melastatin subgroup of transient receptor potential family ion channels (Nagamine et al., 1998). It is expressed in various organs, including immune cells of phagocytic lineage (Sano et al., 2001; Heiner et al., 2006), pancreatic β cells (Hara et al., 2002; Togashi et al., 2006), and brain neurons (Perraud et al., 2001; Nagamine et al., 1998). Physiological processes that have been shown to require TRPM2 channel activity include immune cell activation (Yamamoto et al., 2008), insulin secretion (Uchida et al., 2011), and the central regulation of body temperature by heat-sensitive neurons in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus (Song et al., 2016). On the other hand, under pathological conditions, activation of TRPM2 channels in response to oxidative stress has been shown to underlie neuronal cell death, such as postischemic brain injury or chronic neurodegenerative diseases (Hara et al., 2002; Kaneko et al., 2006; Fonfria et al., 2005; Hermosura et al., 2008).

The TRPM2 protein is a homotetrameric Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Its transmembrane domain, which forms the channel pore, is flanked by large N- and C-terminal domains. Pore opening is triggered by simultaneous binding of cytosolic ADP ribose (ADPR; Perraud et al., 2001; Sano et al., 2001) and Ca2+ (McHugh et al., 2003; Csanády and Törocsik, 2009), but also requires the presence of phosphatydyl-inositol-4-5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the inner membrane leaflet (Tóth and Csanády, 2012). These basic functional features of TRPM2 channels have remained unaltered since the first appearance of ancient TRPM2 channels in choanoflagellates (Iordanov et al., 2019). The TRPM2 C-terminal region comprises an ∼270 amino acid domain termed NUDT9-H for its homology to the soluble mitochondrial enzyme NUDT9, a Nudix-family ADPR pyrophosphatase that hydrolyses ADPR into AMP and ribose-5-phosphate (r-5-P; Perraud et al., 2001). The NUDT9-H domain of human TRPM2 (hsTRPM2) is catalytically inactive (Iordanov et al., 2016), but TRPM2 channels from two invertebrate species, the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta (srTRPM2) and the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis (nvTRPM2), were shown to be active chanzymes that cleave ADPR. Such functional dichotomy is explained by the presence of an intact “Nudix-box” sequence motif in the NUDT9-H domains of invertebrate TRPM2 channels, but by the appearance of mutations in key Nudix-box positions in vertebrates (Kühn et al., 2016; Iordanov et al., 2019). Because at the same evolutionary time pore mutations that cause irreversible inactivation also appeared, it was suggested that for invertebrate channels ligand cleavage by the NUDT9-H domain served as an inactivation mechanism which was replaced by pore inactivation in vertebrates (Iordanov et al., 2019). Surprisingly, nvTRPM2 channels were shown to remain activatable by ADPR following deletion of the nvNUDT9-H domain, suggesting the presence of a second ADPR-binding site outside this domain (Kühn et al., 2016).

Recently, high-resolution structures of TRPM2 channel proteins from several species, in various conformations, have been solved by cryo-electron microscopy. The Ca2+-bound structure of the nvTRPM2 protein (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession no. 6CO7; Zhang et al., 2018), obtained in the absence of ADPR, revealed a three-tiered architecture, conserved among TRPM-family channels (Guo et al., 2017; Autzen et al., 2018; Winkler et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2018), consisting of a transmembrane layer and two cytosolic layers. In this structure, the location of the activating Ca2+-binding site could be identified within the transmembrane region, but the nvNUDT9-H domain was not resolved, suggesting that it is flexibly attached to the rest of the protein. In contrast, in structures of zebrafish (Danio rerio) TRPM2 (drTRPM2; PDB accession nos. 6DRK and 6DRJ [Huang et al., 2018]; 6PKV, 6PKW, 6D73, and 6PKX [Yin et al., 2019]) and hsTRPM2 (PDB accession numbers 6MIX, 6MIZ, and 6MJ2 [Wang et al., 2018]; 6PUO, 6PUR, 6PUS, and 6PUU [Huang et al., 2019]), the NUDT9-H domains are seen to form an additional cytosolic layer that undergoes pronounced conformational changes in response to ADPR binding to the channel protein. Whereas ADPR bound at the NUDT9-H domain has been resolved so far only for hsTRPM2 (6PUS; Huang et al., 2019), a molecule of ADPR bound in a cleft of the MHR1/2 region of the large N-terminal domain was clearly resolved in ADPR-bound structures of both drTRPM2 (PDB accession no. 6DRJ; Huang et al., 2018) and hsTRPM2 (PDB accession no. 6PUS; Huang et al., 2019). Mutations of conserved residues in this “N-terminal–binding site” abrogated channel function, providing evidence for its involvement in channel activation (Huang et al., 2018, 2019; but cf. Wang et al., 2018). On the other hand, unlike for nvTRPM2 (Kühn et al., 2016), for vertebrate TRPM2 channels, the presence of an intact NUDT9-H domain also seemed indispensable for channel function, as mutations in (Yu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019) or deletion of (Wang et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019) the NUDT9-H domain abrogated channel activity for both drTRPM2 and hsTRPM2. The current understanding is that in ancient (invertebrate) TRPM2 channels, the N-terminal site served to activate the channel, whereas the main task of the C-terminal site was to clear away the activating ligand. Over the course of evolution, the C-terminal site lost its enzymatic activity but gained more functional relevance for channel gating. However, the precise contributions of the N- and C-terminal sites to TRPM2 channel function in various species are still not entirely clear, and the nucleotide-binding preferences of the two sites have not yet been sorted out.

The aim of the present study was to exploit the enzymatic activity of invertebrate NUDT9-H domains for selective determination of nucleotide-binding affinities at the two sites in nvTRPM2. A further aim was to confirm whether the ADPR-binding site responsible for activation of the ancient nvTRPM2 channel is identical to the N-terminal site identified in the vertebrate channel structures. Finally, we quantitatively assessed the importance for channel gating of conserved residues seen to interact with ADPR in the N-terminal site.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

For expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes, the full-length nvTRPM2 gene was subcloned into the pGEMHE vector as described previously (Zhang et al., 2018). Replacement of the codons encoding amino acids 1208–1209 or 1242–1243, respectively, by double stop codons to generate 1208STOP and 1242STOP constructs, and point mutations targeting the N-terminal site, were implemented using the QuickChange II XL mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). To generate the 1208CUT deletion construct, the QuickChange kit was used to introduce an XbaI restriction site into nvTRPM2(1208STOP)-pGEMHE following its double stop codon at positions 1208–1209 (forward primer 5′-TTAAACAGGGTGTTAGATTGATAGTCTAGAACTCGGGCTCACGCC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGCGTGAGCCCGAGTTCTAGACTATCAATCTAACACCCTGTTTAA-3′). Digestion of the resulting plasmid by XbaI (New England Biolabs) excised the DNA fragment between the engineered XbaI site and a second XbaI site present in the pGEMHE multiple cloning site downstream of the insert. The resulting two fragments (∼1.0 kb and ∼6.7 kb) were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The 6.7-kb fragment was excised from the gel, purified (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit; Qiagen), and ligated using T4 ligase (New England Biolabs). All constructs were verified by full insert sequencing (LGC Genomics GmbH). cDNA was linearized with NheI, transcribed in vitro using T7 polymerase (mMessage mMachine T7 Kit; Thermo Fisher), and cRNA stored at −80°C. For bacterial expression of nvNUDT9-H, the DNA sequence encoding nvTRPM2 residues 1271–1551, with added C-terminal Twin-Strep-tag (General Biosystems), was incorporated into the pJ411 vector as described previously (Iordanov et al., 2019).

Protein expression and purification

The isolated nvNUDT9-H domain was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) and purified as described previously (Iordanov et al., 2019). In brief, bacterial cultures induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thio-galactopyranoside overnight at 25°C were lysed by sonication, centrifuged (15,000×g for 30 min at 4°C), and the protein purified from the supernatant using Strep-Tactin affinity chromatography (IBA GmbH), followed by gel filtration (Superdex 200 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare). The affinity tag was not removed. Protein purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE and protein identity confirmed by the band position and the main peak position on the gel filtration profile. Protein yield, determined spectrophotometrically using a theoretical molar extinction coefficient (ε0 = 58,320 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm), was ∼5 mg/liter of culture. The purified protein was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C until use.

Enzymatic activity assay

ADPR pyrophosphatase activity of purified nvNUDT9-H was quantified through colorimetric detection of Pi liberated from the ADPR cleavage products AMP and r-5-P by coapplied alkaline phosphatase (AP), as described previously (Iordanov et al., 2019). In brief, 150-µl volumes of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, and 16 mM MgCl2) containing 0.5 nM purified nvNUDT9-H protein, 2–3 U bovine AP, and 5–160 µM of the tested ADPR analogue (ADPR, 2′-deoxy-ADPR [dADPR], 8-Br-ADPR [Br-ADPR], or 1,N6-ethenoadenosine-5′-O-diphosphoribose [ε-ADPR]) were incubated for 4–5 min at room temperature. The reactions were stopped and the liberated Pi visualized by adding 850 µl coloring solution (6:1 vol/vol ratio mixture of 0.42% ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate in 1N H2SO4 and 10% L-ascorbic acid) followed by incubation for 20 min at 45°C. Absorption at 820 nm was measured (NanoPhotometer P300; Implen GmbH) and compared with that of a standard curve (1–2,000 µM KH2PO4). All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich.

The analogue ADPR-2′-phosphate (ADPRP) contains an additional phosphate group at the 2′ position and is cleaved into r-5-P plus adenosine 2′,5′-diphosphate (AMP-2′-P) by nvNUDT9-H. However, the 2′-phosphate is always accessible to the AP, regardless of whether the pyrophosphate bond of the nucleotide has been hydrolyzed or not. To assess nvNUDT9-H hydrolytic activity on ADPRP, 150-µl volumes of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, and 1 mM MgCl2) containing 1 nM purified nvNUDT9-H and 5–160 µM ADPRP were incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The hydrolytic reaction was then stopped by addition of 1.5 mM EDTA, which chelates the Mg2+ necessary for nvNUDT9-H activity (Iordanov et al., 2019). Subsequently, 2–3 U bovine AP was added for 10 min at room temperature to liberate all the accessible phosphates, which include all the 2′-phosphates (from unhydrolyzed ADPR-2′-P plus the hydrolysis product AMP-2′-P), in addition to the phosphates that had become accessible as a consequence of ADPRP hydrolysis (5′-phosphate of AMP-2′-P plus 5-phosphate of r-5-P). Total released free phosphate was quantitated as for the other ADPR analogues. A set of identically treated samples, containing 5–160 µM ADPRP but no nvNUDT9-H, was used to establish “background” phosphate, originating from the 2′-phosphate of ADPRP, which was then subtracted from the total phosphate released in the respective nvNUDT9-H–containing samples.

The molecular turnover rate (kcat) of nvNUDT9-H toward its substrates was calculated from the reaction rates at the highest (saturating) substrate concentration of the dose–response curves; not more than 10% of the initial substrate was hydrolyzed in this condition. All assays were performed at least in triplicate, and data are displayed as mean ± SEM.

Functional expression of nvTRPM2 constructs in Xenopus oocytes

Xenopus oocytes were isolated, collagenase digested, and injected with 0.1–10 ng cRNA encoding WT or mutant nvTRPM2, nvTRPM2(1208STOP), nvTRPM2(1208CUT), or nvTRPM2(1242STOP) as described previously (Zhang et al., 2018). Injected oocytes were stored at 18°C, and recordings were done 1–3 d after injection.

Electrophysiology

Excised inside-out patch-clamp recording of nvTRPM2 currents was done as described previously (Zhang et al., 2018). Pipette (extracellular) solution contained (in mM) 140 Na-gluconate, 2 Mg-gluconate2, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH); a 140 mM NaCl–based solution for the pipette electrode was carefully layered on top (Csanády and Törocsik, 2009). In some experiments (e.g., to measure intracellular [Ca2+] dependence of channel activity), 1 mM EGTA was also included in the pipette solution. Bath (cytosolic) solution contained (in mM) 140 Na-gluconate, 2 Mg-gluconate2, 10 HEPES, and 1 EGTA (pH 7.1 with NaOH) plus 0–760 µM Ca-gluconate2 to obtain “zero” (∼1 nM) or 0.03–1 µM Ca2+. To obtain 1.75–125 µM free [Ca2+], EGTA was omitted from the bath and 10 µM to 1 mM Ca-gluconate2 was added (Csanády and Törocsik, 2009). The bath electrode (in 3 M KCl) was connected to the cytosolic solution through a KCl–agar bridge. Recordings were obtained at 25°C at a membrane potential of −20 mV under continuous superfusion of the cytosolic patch surface. The composition of the cytosolic solution could be exchanged using electronic valves (ALA-VM8; ALA Scientific Instruments); the exchange time constant was <50 ms. Currents were recorded at a bandwidth of 2 kHz (Axopatch 200B; Molecular Devices), digitized at 10 kHz (Digidata 1440A; Molecular Devices), and saved to disk (Pclamp10; Molecular Devices). Na2-ADPR was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and sodium salts of dADPR, ADPRP, Br-ADPR, and ε-ADPR were obtained from Biolog Life Science Institute. Nucleotides were diluted into the bath solution from 10–200 mM aqueous stocks, pH adjusted to 7.1 using NaOH. Dioctanoyl PIP2 sodium salt (Cayman Chemical) was diluted into the bath solution from a 2.5 mM aqueous stock.

Analysis of current recordings

To obtain dose–response curves for nucleotides (Figs. 1, 2, 5, and 6) or Ca2+ (Fig. 7), fractional currents were calculated by dividing mean current in a test segment by mean current in saturating nucleotide plus saturating Ca2+, in bracketing segments of recording from the same patch. To estimate unitary current amplitudes (Fig. S2 B), all-points histograms, generated from recordings with well resolved unitary transitions after digital filtering at 200 Hz, were fitted by multiple Gaussian functions.

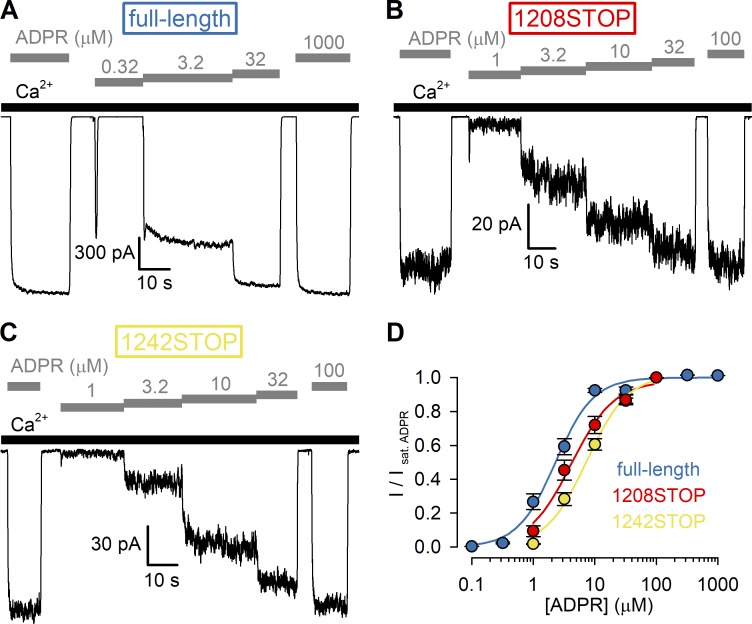

Figure 1.

ADPR affinity for channel activation is intact for nvTRPM2 channels lacking the NUDT9-H domain. (A–C) Macroscopic inward Na+ currents at −20 mV membrane potential activated by cytosolic exposure to various concentrations of ADPR (gray bars) plus 125 µM Ca2+ (black bars) recorded from inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes preinjected with cRNA encoding full-length (A), 1208STOP (B), or 1242STOP (C) nvTRPM2. (D) Steady-state currents in the presence of test [ADPR], normalized to the mean of the currents during bracketing exposures of the same patch to saturating (100–1,000 µM) ADPR, plotted as a function of [ADPR] for full-length (dark blue symbols), 1208STOP (red symbols), and 1242STOP (yellow symbols) nvTRPM2. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 to 32 independent experiments. Fits to the Hill equation (colored lines) yielded fit parameters of EC50 = 2.3 ± 0.2 µM, nH = 1.4 ± 0.1 for full-length; EC50 = 4.2 ± 0.6 µM, nH = 1.2 ± 0.2 for 1208STOP; and EC50 = 7.4 ± 0.7 µM, nH = 1.3 ± 0.1 for 1242STOP nvTRPM2.

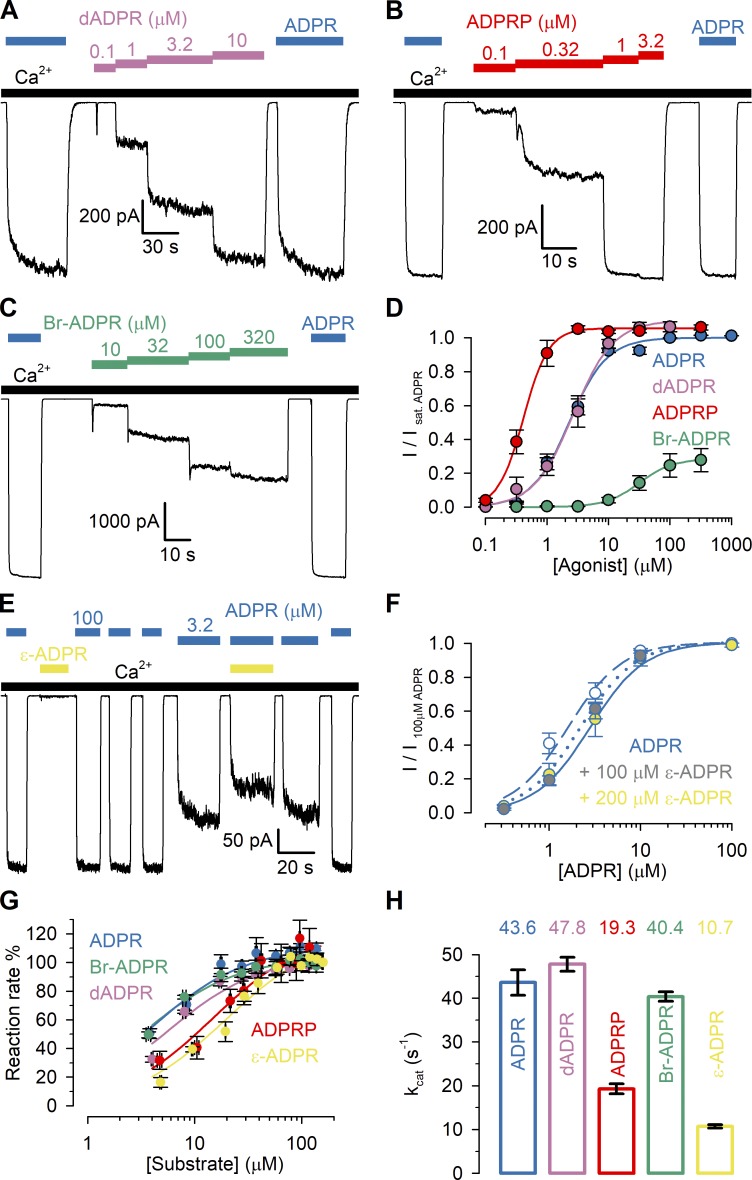

Figure 2.

Apparent affinities of ADPR analogues for nvTRPM2 N- and C-terminal sites. (A–C) Macroscopic nvTRPM2 currents activated by cytosolic exposure to either 100 µM ADPR (dark blue bars) or various concentrations of dADPR (A; purple bars), ADPRP (B; red bars), or Br-ADPR (C; green bars) in the presence of 125 µM Ca2+ (black bars). (D) Steady-state currents in the presence of various test nucleotide concentrations, normalized to the mean of the currents during bracketing exposures of the same patch to 100 µM ADPR, plotted as a function of nucleotide concentration for ADPR (dark blue symbols, replotted from Fig. 1 D), dADPR (purple symbols), ADPRP (red symbols), and Br-ADPR (green symbols). Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 to 32 independent experiments. EC50 values, obtained from fits to the Hill equation (colored lines), are summarized in Table 1 (center column). Maximal fractional activation was 1.1 ± 0.04 for dADPR, 1.06 ± 0.03 for ADPRP, and 0.29 ± 0.01 for Br-ADPR; Hill coefficients were nH = 1.3 ± 0.2 for dADPR, nH = 2.1 ± 0.4 for ADPRP, and nH = 1.6 ± 0.2 for Br-ADPR. (E) Macroscopic nvTRPM2 currents in 3.2 or 100 µM ADPR (dark blue bars), in 200 µM ε-ADPR (first yellow bar), and in 3.2 µM ADPR + 200 µM ε-ADPR (second yellow bar), all in the presence of 125 µM Ca2+ (black bars). (F) Normalized ADPR dose–response curves of nvTRPM2 in the absence of ε-ADPR (blue-white symbols) and in the presence of a fixed concentration of either 100 µM (blue-gray symbols) or 200 µM (blue-yellow symbols) ε-ADPR. For all ADPR concentrations, currents with or without ε-ADPR were obtained within the same patches and normalized to the mean of the currents during bracketing exposures to 100 µM ADPR alone. Data represent mean ± SEM, from 4 to 18 independent experiments. The three dose–response plots were simultaneously fitted (dark blue dashed, dotted, and solid curves) to the equation I/I100ADPR = Îmax × [ADPR]n/(EC50 × (1 + [ε-ADPR]/IC50)n + [ADPR]n), with Îmax, EC50, n, and IC50 as free parameters. This global fit returned parameter estimates Îmax = 1.0 ± 0.0, EC50 = 1.6 ± 0.2 µM (for ADPR), n = 1.5 ± 0.1, and IC50 = 269 ± 91 µM (for ε-ADPR). (G) Rates of nucleotide hydrolysis by the isolated, purified nvNUDT9-H domain as a function of substrate concentration, using ADPR (dark blue symbols; replotted from Iordanov et al., 2019), dADPR (purple symbols), ADPRP (red symbols), Br-ADPR (green symbols), or ε-ADPR (yellow symbols) as the substrate. Reaction rates (mean ± SEM from three to eight independent experiments) were normalized to those observed at the highest substrate concentration. Solid colored lines represent fits to the Michaelis–Menten equation, and obtained Km values are plotted in Table 1 (left column). (H) Molecular turnover numbers (kcat) of isolated, purified nvNUDT9-H for the five substrates in G, measured at saturating substrate concentrations. Data represent mean ± SEM from three to eight independent experiments.

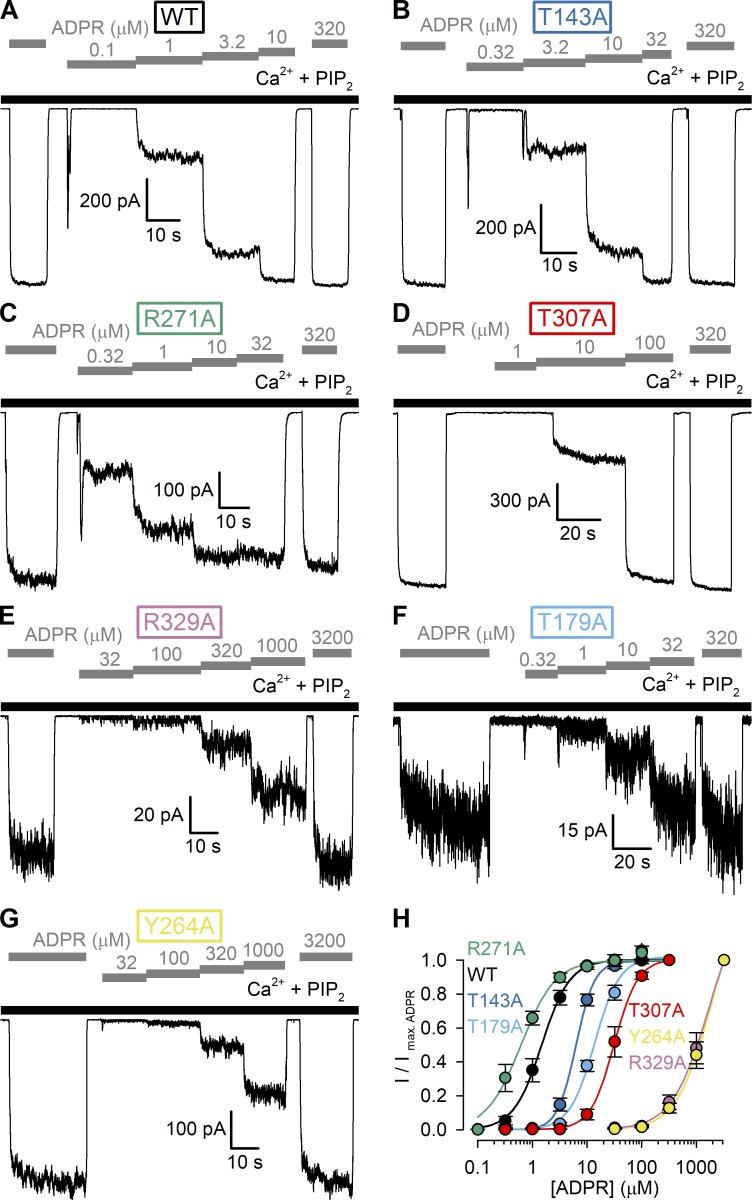

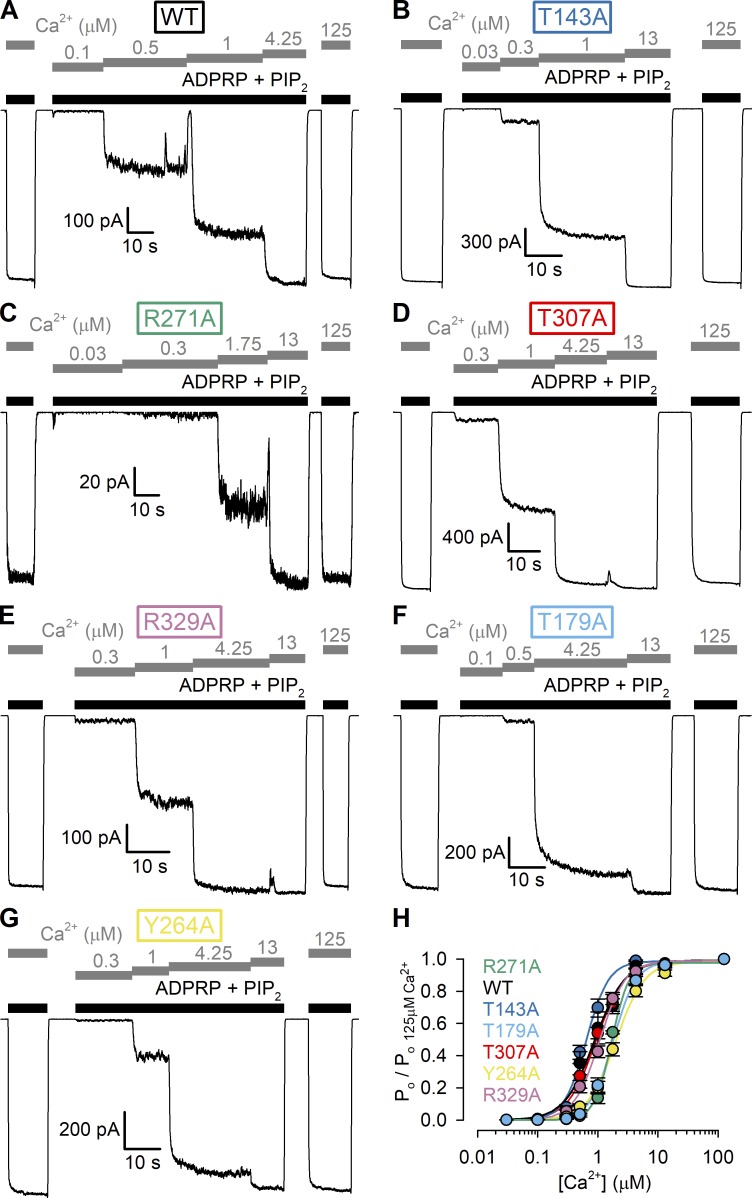

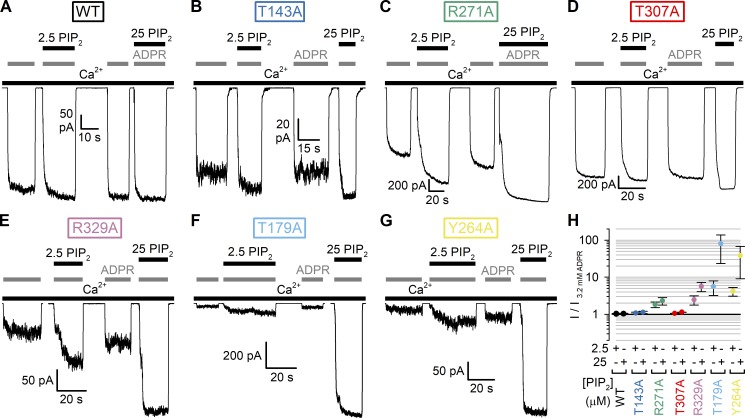

Figure 5.

Apparent affinities for channel activation by ADPR of WT nvTRPM2 and MHR1/2 domain mutants. (A–G) Macroscopic inside-out patch currents of WT (A), T143A (B), R271A (C), T307A (D), R329A (E), T179A (F), and Y264A (G) nvTRPM2 activated by increasing concentrations of ADPR (gray bars) in the presence of 125 µM Ca2+ + 2.5 µM PIP2 (black bars). (H) ADPR dose–response curves of fractional currents, normalized to the mean of the currents observed during bracketing applications of saturating ADPR in the same patch, for WT and mutant nvTRPM2 channels (color coding follows construct labeling in A–G). Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 to 17 independent experiments. Colored lines are fits to the Hill equation yielding fit parameters EC50 = 1.5 ± 0.1 µM and nH = 1.7 ± 0.2 for WT, EC50 = 6.3 ± 0.3 µM and nH = 2.6 ± 0.2 for T143A, EC50 = 0.62 ± 0.05 µM and nH = 1.4 ± 0.2 for R271A, EC50 = 31 ± 2 µM and nH = 2.0 ± 0.2 for T307A, EC50 = 1,710 ± 934 µM and nH = 1.3 ± 0.3 for R329A, EC50 = 14 ± 1 µM and nH = 1.9 ± 0.2 for T179A, and EC50 = 1,867 ± 936 µM and nH = 1.4 ± 0.3 for Y264A nvTRPM2.

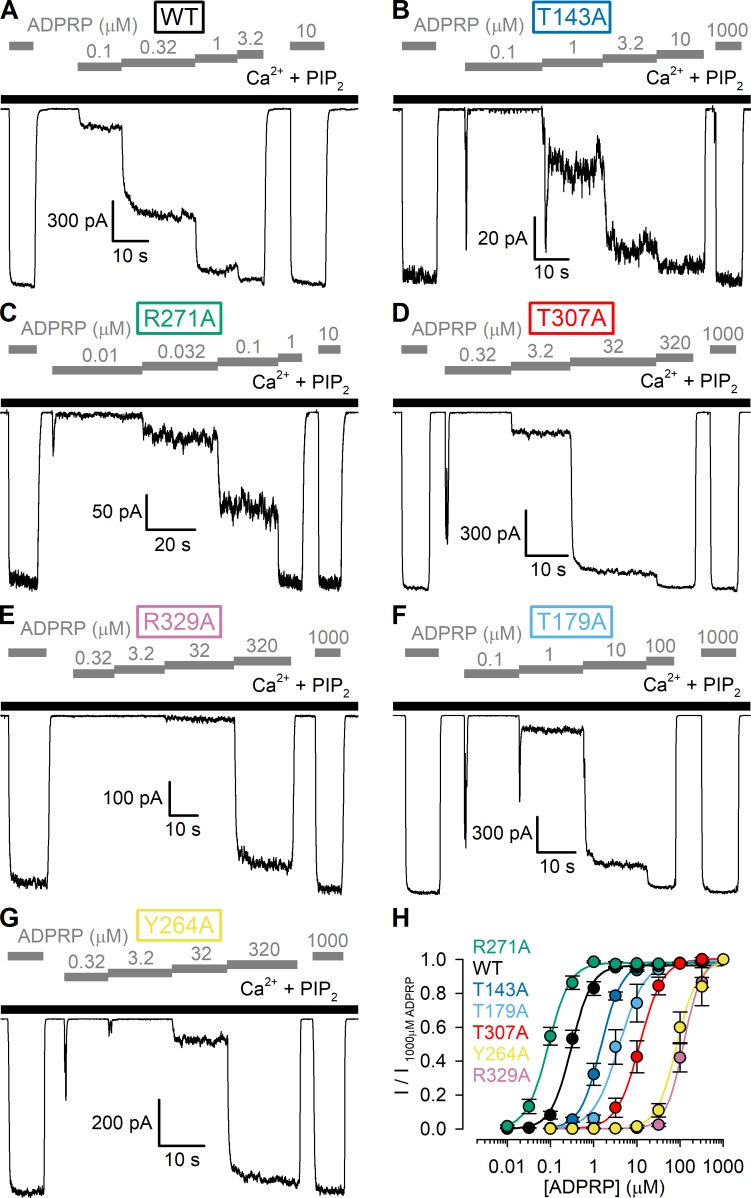

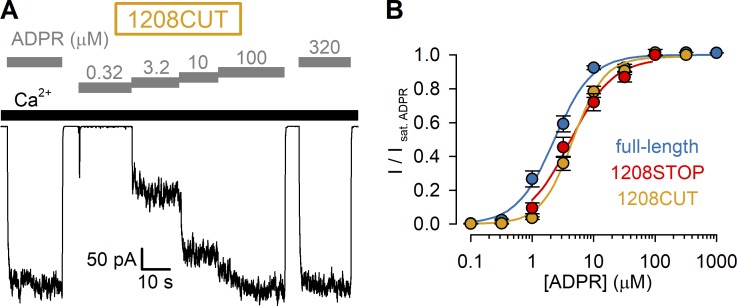

Figure 6.

Apparent affinities for channel activation by ADPRP of WT nvTRPM2 and MHR1/2 domain mutants. (A–G) Macroscopic inside-out patch currents of WT (A), T143A (B), R271A (C), T307A (D), R329A (E), T179A (F), and Y264A (G) nvTRPM2 activated by increasing concentrations of ADPRP (gray bars) in the presence of 125 µM Ca2+ + 2.5 µM PIP2 (black bars). (H) ADPRP dose–response curves of fractional currents, normalized to the mean of the currents observed during bracketing applications of saturating ADPRP in the same patch, for WT and mutant nvTRPM2 channels (color coding follows construct labeling in A–G). Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 to 18 independent experiments. Colored lines are fits to the Hill equation yielding fit parameters EC50 = 0.31 ± 0.02 µM and nH = 1.8 ± 0.2 for WT, EC50 = 1.5 ± 0.1 µM and nH = 1.8 ± 0.1 for T143A, EC50 = 0.089 ± 0.005 µM and nH = 1.7 ± 0.2 for R271A, EC50 = 12 ± 1 µM and nH = 1.6 ± 0.2 for T307A, EC50 = 121 ± 7 µM and nH = 2.1 ± 0.2 for R329A, EC50 = 3.9 ± 0.5 µM and nH = 1.4 ± 0.2 for T179A, and EC50 = 85 ± 8 µM and nH = 1.8 ± 0.3 for Y264A nvTRPM2.

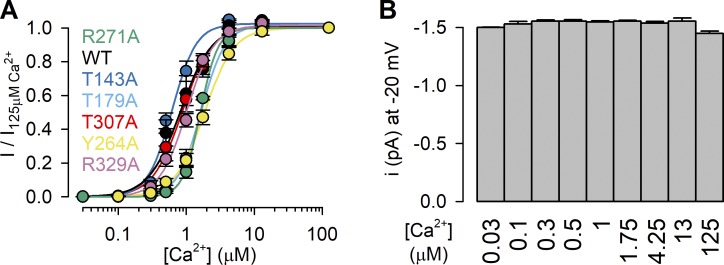

Figure 7.

Apparent affinities for channel activation by Ca2+ of WT nvTRPM2 and MHR1/2 domain mutants. (A–G) Macroscopic inside-out patch currents of WT (A), T143A (B), R271A (C), T307A (D), R329A (E), T179A (F), and Y264A (G) nvTRPM2 activated by increasing concentrations of Ca2+ (gray bars) in the presence of saturating ADPRP + 2.5 µM PIP2 (black bars). [ADPRP] is 10 µM in A and C, 100 µM in B and F, and 1,000 µM in D, E, and G. (H) Ca2+ dose–response curves of fractional Pos, normalized to the mean of the Pos during bracketing applications of 125 µM Ca2+ in the same patch, for WT and mutant nvTRPM2 channels (color coding follows construct labeling in A–G). Fractional Pos (Po/Po;125Ca2+) were obtained by dividing fractional macroscopic current in test [Ca2+] (I/I125Ca2+; Fig. S2 A) by fractional unitary current at the same [Ca2+] (i/i125Ca2+; cf. Fig. S2 B). Data represent mean ± SEM from 5 to 10 independent experiments. Colored lines are fits to the Hill equation yielding fit parameters EC50 = 0.88 ± 0.07 µM and nH = 1.7 ± 0.2 for WT, EC50 = 0.64 ± 0.02 µM and nH = 2.3 ± 0.2 for T143A, EC50 = 1.68 ± 0.04 µM and nH = 3.0 ± 0.2 for R271A, EC50 = 0.93 ± 0.05 µM and nH = 1.9 ± 0.2 for T307A, EC50 = 1.1 ± 0.04 µM and nH = 2.0 ± 0.2 for R329A, EC50 = 1.8 ± 0.1 µM and nH = 2.3 ± 0.1 for T179A, and EC50 = 2.0 ± 0.1 µM and nH = 1.8 ± 0.1 for Y264A nvTRPM2.

Figure S2.

Correction for pore block by cytosolic Ca2+, for obtaining apparent affinities for channel activation by Ca2+ of WT nvTRPM2 and MHR1/2 domain mutants. (A) Ca2+ dose–response curves of macroscopic currents from Fig. 7, A–G, normalized to the mean of the currents during bracketing applications of 125 µM Ca2+ in the same patch (I/I125Ca2+), for WT and mutant nvTRPM2 channels (color coding follows construct labeling in Fig. 7, A–G). Data represent mean ± SEM from 5 to 10 independent experiments. Colored lines are fits to the Hill equation. (B) Unitary nvTRPM2 current amplitudes (i) at −20 mV in our recording solutions (see Materials and methods), with cytosolic (bath) Ca2+ concentrations indicated below each bar. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 to 14 independent experiments. The Po/Po;125Ca2+ symbols in Fig. 7 H were obtained as (I/I125Ca2+)/(i/i125Ca2+).

Statistics

Data are displayed as mean ± SEM, with the number of experiments indicated in the figure legends. For the electrophysiological recordings, n represents the number of patches (n = 3–44). For the enzymatic activity assays, n = 3–8 from independent technical replicates.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that deletion of the nvNUDT9-H coding sequence results in channels indistinguishable from nvTRPM2(1208STOP). Fig. S2 shows the correction for pore block by cytosolic Ca2+ employed for extracting Ca2+ effects on open probability (Po) for WT nvTRPM2 and MHR1/2 domain mutants.

Results

Apparent affinity for nvTRPM2 channel activation by ADPR is little affected by deletion of the nvNUDT9-H domain

Deletion of the NUDT9-H domain from nvTRPM2 results in channels that remain activatable by ADPR (Kühn et al., 2016), but to what extent such truncation affects channel gating properties remains to be established. To quantitatively assess the potency (half-maximal effective concentration; EC50) for channel activation of nvTRPM2 channels lacking the entire NUDT9-H domain, we reproduced the reported truncation mutant by introducing a double stop codon following amino acid position 1207 (1208STOP) and compared the functional properties of such channels to those of full-length nvTRPM2 by recording macroscopic inward Na+ currents at −20 mV in inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes preinjected with the corresponding cRNA (Fig. 1). Just as for full-length nvTRPM2 (Fig. 1 A), channels truncated at position 1208 (Fig. 1 B) generated macroscopic currents that required coapplication of cytosolic Ca2+ (black bars) and ADPR (gray bars) for activation, although expression levels were markedly reduced for the truncated construct. To obtain normalized dose–response curves (Fig. 1 D; red and dark blue symbols), steady-state currents in various test [ADPR] were normalized to the currents observed in the same patches upon bracketing exposures to saturating ADPR. From fits to the Hill equation (Fig. 1 D; red and dark blue lines), the EC50 for channel activation by ADPR for nvTRPM2(1208STOP) remained within twofold of that of the full-length channel (4.2 ± 0.6 µM vs. 2.3 ± 0.2 µM). Truncation at position 1208 removes, in addition to the nvNUDT9-H domain, the second part of a predicted coiled-coil region (Mei et al., 2006), which forms a second coiled-coil helix in some drTRPM2 structures (Yin et al., 2019). To generate channels that lack the nvNUDT9-H domain but retain the entire predicted coiled-coil region, we also designed a somewhat longer truncation construct by inserting a double stop codon after amino acid position 1241. The resulting truncation mutant (1242STOP) behaved very similarly to the 1208STOP construct (Fig. 1, C and D, yellow symbols).

Although our truncation constructs were terminated using double stop codons, a translational readthrough can in principle not be excluded. We therefore also generated (see Materials and methods) an nvNUDT9-H deletion construct (1208CUT) by eliminating from our expression plasmid the entire DNA sequence encoding for the nvNUDT9-H domain (amino acids 1208–1551). Xenopus oocytes preinjected with cRNA transcribed from this plasmid developed ADPR- and Ca2+-dependent cation currents that were indistinguishable from those of the 1208STOP construct (Fig. S1 A), including the EC50 for activation by ADPR (4.6 ± 0.3 µM; Fig. S1 B).

Figure S1.

Deletion of nvNUDT9-H coding sequence results in channels indistinguishable from nvTRPM2(1208STOP). (A) Macroscopic current activated by cytosolic exposure to increasing concentrations of ADPR (gray bars) plus 125 µM Ca2+ (black bar), recorded from an inside-out patch excised from a Xenopus oocyte preinjected with cRNA encoding nvTRPM2(1208CUT). (B) Steady-state currents in the presence of test [ADPR], normalized to the mean of the currents during bracketing exposures of the same patch to 320 µM ADPR, plotted as a function of [ADPR] (orange symbols). Data represent mean ± SEM from 5 to 12 independent experiments. Fits to the Hill equation (colored lines) yielded fit parameters of EC50 = 4.6 ± 0.3 µM and nH = 1.7 ± 0.2. Red (1208STOP) and dark blue (full-length) symbols replot data from Fig. 1 D for comparison.

Nucleotide affinity profiles for channel activation and ligand hydrolysis in nvTRPM2 are markedly different

For hsTRPM2 it is very difficult to functionally dissect the ligand-binding affinities of the N- and C-terminal sites, as the relative contribution to channel activity (the only functional readout) of ligand binding at either site is unclear (Huang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). In contrast, the intact ADPR dependence of gating of NUDT9-H–deleted nvTRPM2 channels (Fig. 1) indicates that in nvTRPM2, unlike in vertebrate TRPM2, the activating ADPR-binding site is not only located outside the nvNUDT9-H domain (Kühn et al., 2016) but also single-handedly responsible for channel activation. On the other hand, we have previously shown that the catalytic activity of nvTRPM2 is solely attributable to the nvNUDT9-H domain, which in its isolated form recapitulates the catalytic properties of the full-length protein (Iordanov et al., 2019). Such functional independence of the two sites offers a unique opportunity to selectively measure the binding affinity of a particular ligand to the nvNUDT9-H domain, as reported by the Km for its hydrolysis (Iordanov et al., 2019), and to the activating site, as reported by the EC50 for channel activation (Fig. 1 D).

Several ADPR analogues have been identified in the past as alternative ligands or inhibitors of hsTRPM2 (Moreau et al., 2013; Tóth et al., 2015; Iordanov et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2018a; Fliegert et al., 2017; Baszczyňski et al., 2019). Among identified hsTRPM2 agonists ADPRP acts as a low-affinity partial agonist (Tóth et al., 2015), whereas dADPR was described as a “super-agonist” because it activated larger maximal whole-cell hsTRPM2 currents compared with ADPR (Fliegert et al., 2017). Among reported antagonists, Br-ADPR was the first identified specific hsTRPM2 inhibitor (Moreau et al., 2013), whereas ε-ADPR acts on hsTRPM2 as a low-affinity antagonist (Iordanov et al., 2016). For the above ADPR analogues vastly different apparent affinities, ranging from ∼1 µM to ∼300 µM, have been reported.

To characterize the potencies and efficacies of various nucleotides for nvTRPM2 channel activation, we recorded macroscopic inside-out patch currents of WT nvTRPM2 evoked by cytosolic exposure to dADPR (Fig. 2 A, purple bars), ADPRP (Fig. 2 B, red bars), or Br-ADPR (Fig. 2 C, green bars) in the presence of 125 µM cytosolic Ca2+ (black bars). Steady-state currents elicited by increasing concentrations of these nucleotides were normalized to the currents observed in the same patches upon bracketing exposures to saturating ADPR (Fig. 2, A–C, dark blue bars) and plotted as a function of nucleotide concentration (Fig. 2 D); normalized dose–response curves (colored symbols) were fitted by the Hill equation (colored lines). The obtained dose–response curves reveal largely different EC50 values for the various nucleotides toward nvTRPM2 channel activation (Table 1, center column) and also some notable differences relative to earlier reports on hsTRPM2. In particular, for nvTRPM2, Br-ADPR (Fig. 2 D, green) is a low-affinity (EC50 ∼30 µM) partial agonist with a maximal efficacy of ∼0.3 relative to ADPR, whereas dADPR (Fig. 2 D, purple; EC50 ∼2.7 µM) is similarly efficacious and potent as ADPR (Fig. 2 D, dark blue, EC50 ∼2.3 µM). Intriguingly, ADPRP (Fig. 2 D, red), which is a low-affinity partial agonist of hsTRPM2 (Tóth et al., 2015), is not only a full agonist of nvTRPM2 but also displays a higher affinity (EC50 ∼0.4 µM) than ADPR, consistent with an earlier report (Kühn et al., 2016). In the presence of 125 µM cytosolic Ca2+, exposure to 200 µM ε-ADPR alone induced only tiny currents (Fig. 2 E, first yellow bar), but coapplication of 200 µM ε-ADPR reduced by ∼25% the currents elicited by 3.2 µM ADPR (Fig. 2 E, second yellow bar), signaling a dose-dependent rightward shift in the ADPR dose–response curve in the presence of the analogue (Fig. 2 F). This identifies ε-ADPR as a low-affinity antagonist for nvTRPM2 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration; IC50 ∼270 µM), just as for hsTRPM2.

Table 1. Apparent affinities for nucleotide binding of nvTRPM2 N- and C-terminal sites.

| Ligand | Km for nvNUDT9-H (µM) | EC50 (IC50) for nvTRPM2(µM) | EC50 (IC50) for hsTRPM2 (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADPR | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 (Tóth et al., 2015) |

| dADPR | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | n.d. |

| Br-ADPR | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 31.9 ± 2.8 | n.d. |

| ε-ADPR | 19.6 ± 2.6 | (IC50) 269 ± 91 | (IC50) 112 ± 24 (Iordanov et al., 2016) |

| ADPR-2′-phosphate | 14.9 ± 4.0 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 13 ± 1 (Tóth et al., 2015) |

Km values of the isolated nvNUDT9-H domain for hydrolysis of various ADPR analogues (left column), and EC50 for nvTRPM2 channel activation (for ε-ADPR IC50 for inhibition) by the same nucleotides in the presence of 125 µM cytosolic Ca2+ (center column). Data represent mean ± SEM obtained from least-squares fits of the Michaelis–Menten (Km) or Hill (EC50) equation to the respective dose–response curves. Right column lists published EC50 (IC50) values for activation (inhibition) of hsTRPM2 by ADPR analogues; to allow meaningful comparison, only reports that were obtained in inside-out patches, in the presence of saturating cytosolic Ca2+, are listed. n.d., not determined.

In contrast to the variable efficacies and potencies for nvTRPM2 channel activation, the isolated nvNUDT9-H domain showed little selectivity among the same ligands. All five analogues were efficiently hydrolyzed by nvNUDT9-H, with kcat values ranging between ∼11 s−1 and ∼48 s−1 (Fig. 2 H). Moreover, the apparent affinities of the five analogues for binding to nvNUDT9-H, as reported by their Km values, remained within an approximately sixfold range (Fig. 2 G and Table 1, left).

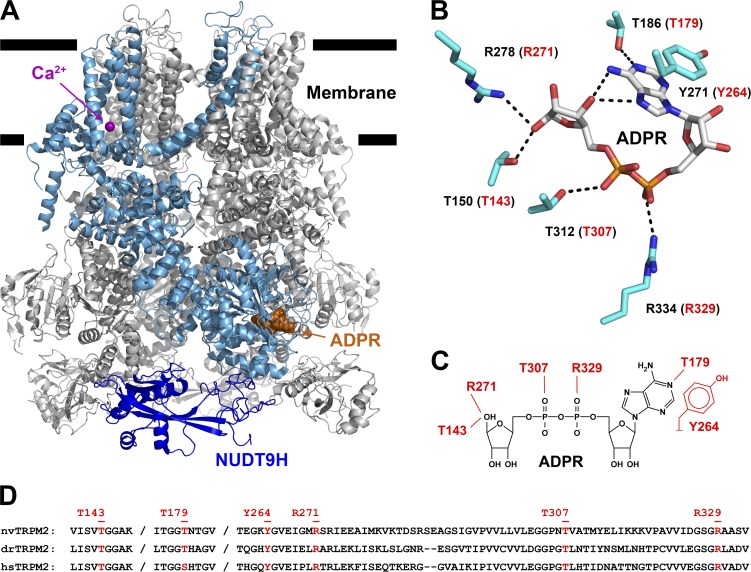

Mutation of a subset of side chains in the predicted N-terminal site reduces maximal Po of nvTRPM2 channels

In vertebrate TRPM2 structures (e.g., PDB accession nos. 6DRJ and 6PUS), the N-terminal ADPR-binding site (Fig. 3 A, bound ADPR shown in orange spacefill) is formed by multiple noncontiguous peptide segments that span ∼185 residues in primary sequence (Fig. 3 D). Several key backbone and side-chain interactions with the bound nucleotide appear identical between drTRPM2 and hsTRPM2 and involve amino acids that are also conserved in nvTRPM2 (Fig. 3 D, red; Huang et al., 2018). To address the contribution to ADPR binding of the corresponding region in nvTRPM2, we targeted six side chains for mutagenesis (Fig. 3 B). In drTRPM2 the T186 and Y271 side chains form a hydrogen bond and a pi–pi stacking interaction, respectively, with the adenine base, the R334 and T312 side chains form polar contacts with the ADPR α- and β-phosphates, respectively, and the T150 and R278 side chains form hydrogen bonds with the terminal ribose (Fig. 3 B, black labels and black dotted lines). The corresponding residues in nvTRPM2 are T179, Y264, R329, T307, T143, and R271 (Fig. 3, B and C, red labels).

Figure 3.

Amino acid side chains interacting with ADPR bound in the MHR1/2 domain. (A) Cartoon representation of drTRPM2 structure solved in the presence of ADPR+Ca2+ (PDB accession no. 6DRJ). One subunit is highlighted in light blue, except for the NUDT9-H domain, which is shown in dark blue. ADPR is represented in orange spacefill and Ca2+ as purple sphere. (B) Stick representation of ADPR bound in the MHR1/2 domain of drTRPM2 and six amino acid side chains (black labels) in contact with the nucleotide. Dotted black lines represent polar contacts identified by PyMOL. Red labels in parentheses refer to corresponding nvTRPM2 residues. (C) Schematic representation of ADPR and expected interacting residues in the MHR1/2 domain of nvTRPM2. (D) Sequence alignment of nvTRPM2, drTRPM2, and hsTRPM2 peptide segments involved in ADPR coordination in the N-terminal site. Residues targeted for mutagenesis are highlighted in red, with nvTRPM2 sequence numbering shown on top.

We mutated each of the six target residues, one at a time, to alanine and studied the resulting mutant nvTRPM2 channels in inside-out patch-clamp experiments (Fig. 4). Just as for WT nvTRPM2, in the presence of Ca2+ (125 µM), large macroscopic currents could be activated for each of the six mutants by cytosolic exposure to very high concentrations (3.2 mM) of ADPR (Fig. 4, A–G, gray bars). Under such conditions, Po of WT channels is close to unity (Iordanov et al., 2019), and addition of exogenous short-chain PIP2 causes only marginal additional stimulation (Zhang et al., 2018; Fig. 4 A). Similarly small fractional stimulation by 2.5 and 25 µM PIP2 was also observed for the T143A and T307A mutants (Fig. 4, B, D, and H, dark blue and red symbols), suggesting that their Pos are also close to unity. In contrast, macroscopic currents were stimulated by approximately twofold for R271A (Fig. 4, C and H, green symbols), approximately sixfold for R329A (Fig., 4 E and H, purple symbols), ∼40-fold for Y264A (Fig. 4, G and H, yellow symbols), and ∼80-fold for T179A (Fig. 4, F and H, light blue symbols) upon exposure to 25 µM PIP2. These robust PIP2 responses indicate that channel Po in 125 µM Ca2+ + 3.2 mM ADPR must be substantially reduced for R271A and R329A and vanishingly small for T179A, and Y264A nvTRPM2 channels.

Figure 4.

PIP2 responses of WT and MHR1/2 domain mutant nvTRPM2 channels. (A–G) Macroscopic inside-out patch currents activated by 3.2 mM ADPR (gray bars) + 125 µM Ca2+ (long black bars) in the absence or presence of added 2.5 or 25 µM dioctanoyl-PIP2 (short black bars) for WT (A), T143A (B), R271A (C), T307A (D), R329A (E), T179A (F), and Y264A (G) nvTRPM2. (H) Fractional activation of WT and mutant nvTRPM2 channels by 2.5 and 25 µM PIP2 (color coding follows construct labeling in A–G). Currents in 2.5 or 25 µM PIP2 were normalized to those obtained without added PIP2 in the same patch. Data represent mean ± SEM from three or four independent experiments.

Mutation of several side chains in the predicted N-terminal site dramatically increases EC50 for nvTRPM2 channel activation by ADPR analogues

We next studied for all six mutants the apparent affinities for channel activation by ADPR by exposing the cytosolic faces of inside-out macropatches to a series of ADPR concentrations, bracketed by exposures to a high concentration (0.32 or 3.2 mM) of ADPR (Fig. 5, A–G). To enhance channel currents for the low-Po mutants, these experiments were performed in the maintained presence of 125 µM Ca2+ plus 2.5 µM PIP2 (Fig. 5, A–G, black bars). Fractional currents in the presence of the test ADPR concentrations, normalized to the mean of the currents in the bracketing high-ADPR segments, were plotted as a function of [ADPR] (Fig. 5 H, colored symbols) and fitted to the Hill equation (Fig. 5 H, colored lines). Of note, for WT nvTRPM2, inclusion of 2.5 µM PIP2 only minimally affected the EC50 for ADPR activation (compare Fig. 5 H, black symbols, and Fig. 1 D, dark blue symbols). Interestingly, the R271A mutation (Fig. 5 C) caused a slight leftward shift of the ADPR dose–response curve, decreasing the EC50 for channel activation by approximately twofold, from 1.5 ± 0.1 µM (WT) to 0.62 ± 0.05 µM (R271A; Fig. 5 H, green vs. black). In contrast, all other mutations caused pronounced rightward shifts in the ADPR dose–response curve (Fig. 5 H, colored vs. black), increasing the EC50 for channel activation by approximately fourfold (T143A; Fig. 5, B and H, dark blue), ∼10-fold (T179A; Fig. 5, F and H, light blue), ∼20-fold (T307A; Fig. 5, D and H, red), and >1,000-fold (R329A and Y264A; Fig. 5, E, G, and H, purple and yellow), as expected for truncations of side chains that are directly involved in ADPR binding.

The currents of the lowest-affinity mutants R329A and Y264A failed to saturate even in 3.2 mM ADPR (Fig. 5 H, purple and yellow), rendering estimation of EC50 values uncertain. Because ADPRP is approximately fivefold more potent compared with ADPR for activating WT nvTRPM2 (Fig. 2 D), we also obtained dose–response relationships for all six mutants using ADPRP as the activating ligand. Indeed, in a set of analogous experiments (Fig. 6, A–G), performed again in the presence of 125 µM Ca2+ plus 2.5 µM PIP2, we could obtain complete ADPRP dose–response curves for all mutants (Fig. 6 H). Apart from providing more reliable EC50 estimates for the low-affinity mutants, the ADPRP dose–response pattern recapitulated that observed for ADPR; the obtained EC50 values spanned more than three orders of magnitude, with similar fractional changes caused by each particular mutation (compare Fig. 6 H to Fig. 5 H).

None of the mutations in the predicted N-terminal site dramatically affects EC50 for channel activation by Ca2+

A subset of the region comprising the N-terminal site was identified in a previous study to form a tandem EF hand for Ca2+ binding (Luo et al., 2018b). To assess a potential effect of our mutations on the sensitivity toward Ca2+ activation, we studied for WT nvTRPM2 and all six mutants the apparent affinities for activation by Ca2+ (Fig. 7, A–G) in the maintained presence of saturating ADPRP plus 2.5 µM PIP2 (black bars). Fractional currents in the presence of test Ca2+ concentrations were normalized to the mean of the currents observed in bracketing segments in 125 µM Ca2+ and corrected for a small reduction in unitary current amplitudes caused by 125 µM cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. S2; cf. Zhang et al., 2018). The resulting normalized Pos were plotted against Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 7 H, symbols) and fitted by the Hill equation (Fig. 7 H, solid lines). Under such conditions, the EC50 for Ca2+ was 0.88 ± 0.07 µM for WT nvTRPM2 (Fig. 7 H, black) and remained within approximately twofold of the WT value for all six N-terminal site mutants (Fig. 7 H, colors).

Discussion

In vertebrate TRPM2 channels, the NUDT9-H domain is catalytically inactive, and both the N-terminal (Huang et al., 2018, 2019) and C-terminal (Huang et al., 2018, 2019; Wang et al., 2018) ADPR-binding sites seem to be involved in channel activation, hampering functional dissection of nucleotide binding at the two sites. Here, we exploited the enzymatic activity of nvTRPM2 (Iordanov et al., 2019), and the functional independence of its N- and C-terminal sites (Fig. 1; Kühn et al., 2016; Iordanov et al., 2019), to selectively study for the first time nucleotide binding at either site of a TRPM2 channel. We observed marked differences between the affinity series for channel activation/inhibition and for enzymatic activity (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The nvNUDT9-H domain showed little selectivity among the five tested nucleotides, with kcat values contained within an approximately fivefold range (Fig. 2 H) and Km values within an approximately sixfold range (Fig. 2 G and Table 1, left). In contrast, the EC50 and IC50 values for channel activation/inhibition by the same nucleotides spanned a range of >600-fold (Fig. 2 D and Table 1, center column). Importantly, the two affinity profiles were clearly uncorrelated, being characterized by a sequence Br-ADPR≤ADPR≤dADPR<ADPRP≤ε-ADPR for nvNUDT9-H, but by a sequence ADPRP<<ADPR≤dADPR<Br-ADPR<<ε-ADPR for the activating site. These results provide a first selective characterization of substrate specificities at the NUDT9-H domain and the activating site, respectively, in a TRPM2 channel.

On the other hand, the affinity series for channel activation by various ADPR analogues was markedly different for nvTRPM2 relative to hsTRPM2. For instance, ADPRP which, compared with ADPR, acts as a low-affinity partial agonist on hsTRPM2 (Tóth et al., 2015) turned out to be the highest-affinity agonist of nvTRPM2, with an EC50 for channel activation approximately fivefold lower than for ADPR (Fig. 2 D and Table 1). Moreover, in earlier reports, two synthetic ADPR analogues were shown to inhibit hsTRPM2 (Moreau et al., 2013) but activate nvTRPM2 (Kühn et al., 2019). This might raise the question whether the activating ADPR-binding site in nvTRPM2 corresponds to the same N-terminal site located in the vertebrate TRPM2 structures, such as ADPR-bound drTRPM2 (PDB accession no. 6DRJ) and hsTRPM2 (PDB accession no. 6PUS). However, we show here that truncations of amino acid side chains corresponding to those that coordinate ADPR in the N-terminal site of vertebrate TRPM2 channels (Fig. 3) robustly affect the sensitivity toward activation of nvTRPM2 channels by nucleotides (Figs. 5 and 6), increasing EC50 by up to three orders of magnitude. Moreover, the nucleotide affinity sequence of the six mutants was the same regardless of whether ADPR or ADPRP was used for channel activation (Figs. 5 H and 6 H). This suggests that the mutations and the removal of the 2′-hydroxyl group from ADPR additively affect the free energy of ligand binding, consistent with the drTRPM2 and hsTRPM2 structures in which none of the targeted side chains interacts with the 2′-hydroxyl group of ADPR. These findings establish that the same N-terminal ADPR-binding site observed in the MHR1/2 domain of vertebrate TRPM2 channels was already present in ancient cnidarians.

Our detailed characterization of the functional effects of the six side-chain truncations provides the first insights into the mechanistic contributions of those side chains to channel gating. To draw such mechanistic inferences, one has to consider the relationship between measured EC50 values for ligand activation and the actual ligand-binding affinities (Kd) for the activating site. By the principle of microscopic reversibility, an activating ligand binds more tightly to the open state than to the closed state, and the EC50 for channel activation is a weighted average of the closed- and open-state affinities. For example, for a channel with a single ligand-binding site,

| (1) |

where and are the ligand dissociation constants of the closed and open channels () and Po;max is the Po of a ligand-bound channel. At the same time, the ratio provides the efficacy of the ligand, i.e., the fold increase in the closed–open equilibrium constant ξ, induced by ligand binding,

| (2) |

where ξmin and ξmax are the closed–open equilibrium constants of unliganded and liganded channels.

Mutation of three side chains involved in adenine or α-phosphate coordination in the N-terminal site (Fig. 3) reduced Po in 3.2 mM ADPR, as reported by robust responses to 2.5 and 25 µM exogenous PIP2 (Fig. 4, E–H, purple, light blue, and yellow symbols). Because for the T179A mutant 3.2 mM ADPR clearly represents a saturating concentration (Fig. 5 H, light blue symbols), for this mutant, Po of fully liganded channels (Po;max) is clearly dramatically reduced (Po;max less than ∼0.0125 without added PIP2). Although for the R329A and Y264A mutants 3.2 mM ADPR failed to saturate the channels (Fig. 5 H, purple and yellow symbols), tentative fits to the dose–response curves (Fig. 5 H, purple and yellow solid lines) suggested maximal Po values only ∼1.5-fold higher than those in 3.2 mM ADPR. Given that for these two mutants exposure to 25 µM PIP2 could stimulate Po in 3.2 mM ADPR by ∼6-fold and ∼40-fold, respectively (Fig. 4 H, purple and yellow symbols), our upper estimates of Po;max are ∼0.25 for R329A and ∼0.038 for Y264A. Thus, these three mutations reduce maximal Po of nvTRPM2 channels, but at the same time, they also dramatically reduce ADPR-binding affinity (Fig. 4, E–H; Fig. 5, E–H; and Fig. 6, E–H, purple, light blue, and yellow symbols). These findings suggest that the T179, R329, and Y264 side chains play important roles not only in ligand binding per se, but also in ligand-induced conformational changes: i.e., their interactions with the bound nucleotide become stronger in the open-channel conformation. As a consequence, upon truncation of these side chains, increases more dramatically than causing, in addition to an increased EC50 (see Eq. 1), a smaller fractional increase in the closed–open equilibrium constant upon ligand binding (see Eq. 2).

In contrast, truncation of the T307 and T143 side chains, involved in contacting the β phosphate and the terminal ribose, respectively (Fig. 3), did not reduce maximal Po, as signaled by no further stimulation by exogenous PIP2 (Fig. 4, B, D and H, dark blue and red symbols) but selectively impaired binding affinity (Fig. 5, B and H; and Fig. 6, B, D and H, dark blue and red symbols). Thus, these contacts substantially contribute to ligand binding, but the strength of the interactions seems little affected by channel opening/closure. As a consequence, truncation of these side chains similarly increases and , yielding an increased EC50 (see Eq. 1) but leaving the efficacy of the ligand unaffected (see Eq. 2).

A stabilizing interaction between the terminal ribose of ADPR and the side chain of the arginine corresponding to R278 in nvTRPM2 is observed both in the drTRPM2 (Fig. 3 B) and hsTRPM2 structures, and truncation of this side chain reduced macroscopic currents for the vertebrate channels (Huang et al., 2018, 2019). Based on those reports, the slight leftward shift in the ADPR and ADPRP dose–response curves of R271A nvTRPM2 channels (Fig. 5, C and H; and Fig. 6, C and H, green symbols) was unexpected. At the same time, the modest stimulation of this mutant by exogenous PIP2 (Fig. 4, C and H, green symbols) signals an approximately twofold reduction in maximal Po. Although in the absence of a high-resolution structure of an ADPR-bound nvTRPM2 N-terminal site we can only speculate on the mechanism of these findings, the simplest explanation for this complex phenotype is a selective decrease in in the mutant: together with a decrease in EC50 (see Eq. 1), such a change would also predict a reduced maximal efficacy for the ligands (see Eq. 2), as observed. For example, using the simplistic single binding site model, the set of parameters , and Po;min = 0.004 for WT nvTRPM2 predicts observable parameters Po;max = 0.8 and EC50 = 1.4 µM, as observed with ADPR as the activating ligand (Fig. 5 H, black symbols). Relative to this situation, an isolated sixfold decrease in to results in observable parameters Po;max = 0.4 and EC50 = 0.7 µM, consistent with our observations on nvTRPM2-R271A (Fig. 5 H, green symbols). Such a scenario would suggest that in WT nvTRPM2, the R271 side chain interferes with ADPR binding in the closed, but not open, state. Validation of that assumption would require an atomic nvTRPM2 structure in which the N-terminal site is ligand bound, but its conformation corresponds to that in the closed-channel state.

In principle, a mutation-induced shift in the apparent affinity for channel activation by a ligand does not necessarily prove that the targeted region forms a binding site for that ligand. Based on Eq. 1, any mutation that reduces Po;max will necessarily increase EC50 for the activating ligand by shifting the equilibrium toward the closed states, which bind the ligand less tightly. For that reason, in TRPM2, which is coactivated by two types of ligand, ADPR and Ca2+, mutations in either of the two ligand-binding sites might increase EC50 even for the other ligand. For example, a mutation in the Ca2+-binding site that reduces the Ca2+ affinity of the channels to an extent that 125 µM Ca2+ is no longer saturating will reduce Po;max for ADPR when assayed in 125 µM Ca2+ and therefore also increase EC50 for ADPR activation. Indeed, a previous study suggested that the region targeted by our mutations forms a Ca2+-binding site (Luo et al., 2018b). To exclude that such a mechanism underlies the up to three orders of magnitude shifts in EC50 for ADPR or ADPRP activation caused by our mutations (Figs. 5 H and 6 H), we assessed the EC50 for Ca2+ activation of the same constructs under conditions in which Po;max remains high even for the mutant channels (in saturating ADPRP plus 2.5 µM PIP2). Under such conditions, EC50 for Ca2+ activation remained within twofold of WT for all mutants (Fig. 7 H), precluding involvement of the target region in the formation of a Ca2+-binding site and consistent with structural (Zhang et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018, 2019) and functional (Zhang et al., 2018) studies that have unanimously pinpointed the latter to be located within the transmembrane domain.

In conclusion, we have shown that in an ancient cnidarian TRPM2 channel the same N-terminal ADPR-binding site observed in vertebrate channel structures is already present and that the N- and C-terminal binding sites are functionally independent. We have selectively measured nucleotide affinity profiles at those two sites and provided first insights into the mechanistic contributions to channel gating of conserved amino acid side chains that line the N-terminal site. Further work will be needed to similarly elucidate the specific properties, and functional contributions to channel gating, of the N- and C-terminal sites in vertebrate TRPM2 channels.

Acknowledgments

Merritt C. Maduke served as editor.

Supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Lendület grant LP2017-14/2017 to L. Csanády) and a Ministry of Human Capacities of Hungary New National Excellence Program (Új Nemzeti Kiválóság Program) award to Semmelweis University. B. Tóth is a János Bolyai Research Fellow, supported by postdoctoral Új Nemzeti Kiválóság Program grants 18-4-SE-132 and 19-4-SE-49.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: B. Tóth, I. Iordanov, and L. Csanády. Data acquisition: B. Tóth and I. Iordanov. Data analysis: B. Tóth and I. Iordanov. Data interpretation: B. Tóth, I. Iordanov, and L. Csanády. Writing manuscript: B. Tóth, I. Iordanov, and L. Csanády.

References

- Autzen H.E., Myasnikov A.G., Campbell M.G., Asarnow D., Julius D., and Cheng Y.. 2018. Structure of the human TRPM4 ion channel in a lipid nanodisc. Science. 359:228–232. 10.1126/science.aar4510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baszczyňski O., Watt J.M., Rozewitz M.D., Guse A.H., Fliegert R., and Potter B.V.L.. 2019. Synthesis of Terminal Ribose Analogues of Adenosine 5′-Diphosphate Ribose as Probes for the Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel TRPM2. J. Org. Chem. 84:6143–6157. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., and Törocsik B.. 2009. Four Ca2+ ions activate TRPM2 channels by binding in deep crevices near the pore but intracellularly of the gate. J. Gen. Physiol. 133:189–203. 10.1085/jgp.200810109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegert R., Bauche A., Wolf Pérez A.M., Watt J.M., Rozewitz M.D., Winzer R., Janus M., Gu F., Rosche A., Harneit A., et al. 2017. 2′-Deoxyadenosine 5′-diphosphoribose is an endogenous TRPM2 superagonist. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13:1036–1044. 10.1038/nchembio.2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfria E., Marshall I.C., Boyfield I., Skaper S.D., Hughes J.P., Owen D.E., Zhang W., Miller B.A., Benham C.D., and McNulty S.. 2005. Amyloid beta-peptide(1-42) and hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity are mediated by TRPM2 in rat primary striatal cultures. J. Neurochem. 95:715–723. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., She J., Zeng W., Chen Q., Bai X.C., and Jiang Y.. 2017. Structures of the calcium-activated, non-selective cation channel TRPM4. Nature. 552:205–209. 10.1038/nature24997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y., Wakamori M., Ishii M., Maeno E., Nishida M., Yoshida T., Yamada H., Shimizu S., Mori E., Kudoh J., et al. 2002. LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol. Cell. 9:163–173. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00438-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiner I., Eisfeld J., Warnstedt M., Radukina N., Jüngling E., and Lückhoff A.. 2006. Endogenous ADP-ribose enables calcium-regulated cation currents through TRPM2 channels in neutrophil granulocytes. Biochem. J. 398:225–232. 10.1042/BJ20060183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosura M.C., Cui A.M., Go R.C., Davenport B., Shetler C.M., Heizer J.W., Schmitz C., Mocz G., Garruto R.M., and Perraud A.L.. 2008. Altered functional properties of a TRPM2 variant in Guamanian ALS and PD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:18029–18034. 10.1073/pnas.0808218105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Winkler P.A., Sun W., Lü W., and Du J.. 2018. Architecture of the TRPM2 channel and its activation mechanism by ADP-ribose and calcium. Nature. 562:145–149. 10.1038/s41586-018-0558-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Roth B., Lü W., and Du J.. 2019. Ligand recognition and gating mechanism through three ligand-binding sites of human TRPM2 channel. eLife. 8:e50175 10.7554/eLife.50175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov I., Mihályi C., Tóth B., and Csanády L.. 2016. The proposed channel-enzyme transient receptor potential melastatin 2 does not possess ADP ribose hydrolase activity. eLife. 5:e17600 10.7554/eLife.17600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov I., Tóth B., Szollosi A., and Csanády L.. 2019. Enzyme activity and selectivity filter stability of ancient TRPM2 channels were simultaneously lost in early vertebrates. eLife. 8:e44556 10.7554/eLife.44556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S., Kawakami S., Hara Y., Wakamori M., Itoh E., Minami T., Takada Y., Kume T., Katsuki H., Mori Y., and Akaike A.. 2006. A critical role of TRPM2 in neuronal cell death by hydrogen peroxide. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 101:66–76. 10.1254/jphs.FP0060128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn F.J., Kühn C., Winking M., Hoffmann D.C., and Lückhoff A.. 2016. ADP-Ribose Activates the TRPM2 Channel from the Sea Anemone Nematostella vectensis Independently of the NUDT9H Domain. PLoS One. 11:e0158060 10.1371/journal.pone.0158060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn F.J.P., Watt J.M., Potter B.V.L., and Lückhoff A.. 2019. Different substrate specificities of the two ADPR binding sites in TRPM2 channels of Nematostella vectensis and the role of IDPR. Sci. Rep. 9:4985 10.1038/s41598-019-41531-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Li M., Zhan K., Yang W., Zhang L., Wang K., Yu P., and Zhang L.. 2018a Selective inhibition of TRPM2 channel by two novel synthesized ADPR analogues. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 91:552–566. 10.1111/cbdd.13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Yu X., Ma C., Luo J., and Yang W.. 2018b Identification of a Novel EF-Loop in the N-terminus of TRPM2 Channel Involved in Calcium Sensitivity. Front. Pharmacol. 9:581 10.3389/fphar.2018.00581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D., Flemming R., Xu S.Z., Perraud A.L., and Beech D.J.. 2003. Critical intracellular Ca2+ dependence of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11002–11006. 10.1074/jbc.M210810200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Z.Z., Xia R., Beech D.J., and Jiang L.H.. 2006. Intracellular coiled-coil domain engaged in subunit interaction and assembly of melastatin-related transient receptor potential channel 2. J. Biol. Chem. 281:38748–38756. 10.1074/jbc.M607591200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C., Kirchberger T., Swarbrick J.M., Bartlett S.J., Fliegert R., Yorgan T., Bauche A., Harneit A., Guse A.H., and Potter B.V.L.. 2013. Structure-activity relationship of adenosine 5′-diphosphoribose at the transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channel: rational design of antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 56:10079–10102. 10.1021/jm401497a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine K., Kudoh J., Minoshima S., Kawasaki K., Asakawa S., Ito F., and Shimizu N.. 1998. Molecular cloning of a novel putative Ca2+ channel protein (TRPC7) highly expressed in brain. Genomics. 54:124–131. 10.1006/geno.1998.5551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraud A.L., Fleig A., Dunn C.A., Bagley L.A., Launay P., Schmitz C., Stokes A.J., Zhu Q., Bessman M.J., Penner R., et al. 2001. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature. 411:595–599. 10.1038/35079100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y., Inamura K., Miyake A., Mochizuki S., Yokoi H., Matsushime H., and Furuichi K.. 2001. Immunocyte Ca2+ influx system mediated by LTRPC2. Science. 293:1327–1330. 10.1126/science.1062473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K., Wang H., Kamm G.B., Pohle J., Reis F.C., Heppenstall P., Wende H., and Siemens J.. 2016. The TRPM2 channel is a hypothalamic heat sensor that limits fever and can drive hypothermia. Science. 353:1393–1398. 10.1126/science.aaf7537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togashi K., Hara Y., Tominaga T., Higashi T., Konishi Y., Mori Y., and Tominaga M.. 2006. TRPM2 activation by cyclic ADP-ribose at body temperature is involved in insulin secretion. EMBO J. 25:1804–1815. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth B., and Csanády L.. 2012. Pore collapse underlies irreversible inactivation of TRPM2 cation channel currents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:13440–13445. 10.1073/pnas.1204702109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth B., Iordanov I., and Csanády L.. 2015. Ruling out pyridine dinucleotides as true TRPM2 channel activators reveals novel direct agonist ADP-ribose-2′-phosphate. J. Gen. Physiol. 145:419–430. 10.1085/jgp.201511377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K., Dezaki K., Damdindorj B., Inada H., Shiuchi T., Mori Y., Yada T., Minokoshi Y., and Tominaga M.. 2011. Lack of TRPM2 impaired insulin secretion and glucose metabolisms in mice. Diabetes. 60:119–126. 10.2337/db10-0276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Fu T.M., Zhou Y., Xia S., Greka A., and Wu H.. 2018. Structures and gating mechanism of human TRPM2. Science. 362:eaav4809 10.1126/science.aav4809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler P.A., Huang Y., Sun W., Du J., and Lü W.. 2017. Electron cryo-microscopy structure of a human TRPM4 channel. Nature. 552:200–204. 10.1038/nature24674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Shimizu S., Kiyonaka S., Takahashi N., Wajima T., Hara Y., Negoro T., Hiroi T., Kiuchi Y., Okada T., et al. 2008. TRPM2-mediated Ca2+influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nat. Med. 14:738–747. 10.1038/nm1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Wu M., Zubcevic L., Borschel W.F., Lander G.C., and Lee S.Y.. 2018. Structure of the cold- and menthol-sensing ion channel TRPM8. Science. 359:237–241. 10.1126/science.aan4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Wu M., Hsu A.L., Borschel W.F., Borgnia M.J., Lander G.C., and Lee S.Y.. 2019. Visualizing structural transitions of ligand-dependent gating of the TRPM2 channel. Nat. Commun. 10:3740 10.1038/s41467-019-11733-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P., Xue X., Zhang J., Hu X., Wu Y., Jiang L.H., Jin H., Luo J., Zhang L., Liu Z., and Yang W.. 2017. Identification of the ADPR binding pocket in the NUDT9 homology domain of TRPM2. J. Gen. Physiol. 149:219–235. 10.1085/jgp.201611675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Tóth B., Szollosi A., Chen J., and Csanády L.. 2018. Structure of a TRPM2 channel in complex with Ca2+ explains unique gating regulation. eLife. 7:e36409 10.7554/eLife.36409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]