Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common type of eukaryotic mRNA modification and has been found in many organisms, including mammals, and plants. It has important regulatory effects on RNA splicing, export, stability, and translation. The abundance of m6A on RNA depends on the dynamic regulation between methyltransferase (“writer”) and demethylase (“eraser”), and m6A binding protein (“reader”) exerts more specific regulatory function by binding m6A modification sites on RNA. Progress in research has revealed important functions of m6A modification in plants. In this review, we systematically summarize the latest advances in research on the composition and mechanism of action of the m6A system in plants. We emphasize the function of m6A modification on RNA fate, plant development, and stress resistance. Finally, we discuss the outstanding questions and opportunities exist for future research on m6A modification in plant.

Keywords: N6-methyladenosine, functional implications, plant, RNA function, stress response

Introduction

More than 150 RNA modifications have been identified as post-transcriptional regulatory markers in a variety of RNA species, including messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), small non-coding RNA (snRNA), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), RNA methylation is one of the post-transcriptional modifications of RNA, and N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common type of RNA methylation modification, accounting for more than 80% of RNA methylation modifications in organism. Current study suggests that the m6A modification plays an important role in RNA fate, such as RNA splicing (Liu et al., 2015, 2017; Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016; Pendleton et al., 2017), RNA stability (Wang et al., 2014; Du et al., 2016; Mishima and Tomari, 2016; Huang et al., 2018), RNA export (Roundtree et al., 2017; Edens et al., 2019), 3′ untranslated region (UTR) processing (Ke et al., 2015; Bartosovic et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2018; Yue et al., 2018), translation (Zhou et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017), and miRNA processing (Alarcón et al., 2015a, b; Bhat et al., 2019). Although the presence of m6A was detected in mammals (Desrosiers et al., 1974; Wei et al., 1975; Schibler et al., 1977) and plants (Kennedy and Lane, 1979; Nichols, 1979) in the 1970s, it had not received much attention because it was considered to be “static” due to the method of detecting m6A sites. However, the discovery of the first m6A demethylase fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) was an exciting development (Jia et al., 2011), as it demonstrated that the m6A modification process is dynamic and reversible in the cell. Subsequently, the methyl-RNA immunoprecipitation combined with RNA sequencing (MeRIP-Seq) method was established for identifying m6A modifications on mRNA in the transcriptome (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). This method relies on the highly specific antibody of m6A to precipitate m6A and then involves high-throughput sequencing to reveal methylated transcripts (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). This method revealed that the m6A site is not uniformly distributed over the mRNA: only some mRNAs have m6A sites, most of which are located near the stop codon and the 3′ UTR (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). At the same time, m6A is highly dynamic, and the level of m6A varies greatly depending on the developmental stage (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). These findings suggested that m6A modification may affect the fate and function of mRNA in cells. As more m6A-related enzymes are identified, the important biological functions played by m6A modification are being gradually unveiled. Although the study of m6A functions was mainly in animal systems, current studies shows that m6A modification also plays important role in regulating plant development (Zhong et al., 2008; Bodi et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2016; Hofmann, 2017; Růžička et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2018; Arribas-Hernández et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018; Scutenaire et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2020) and stress resistance (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2020).

Writers, erasers, readers are the core components of the m6A regulatory system. The writers and erasers are responsible for adding or removing m6A to the conserved sequence “RRACH” (where R = A/G, A is the modified m6A site, and H = A/C/U) (Dominissini et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2014; Lence et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2020), respectively. The readers are responsible for binding m6A sites and play specific regulatory roles for modified-RNA. Writers, erasers, and readers form the basis of a complex regulatory network under the guidance of m6A modification. However, not all RNAs containing the “RRACH” sequence will have m6A added to them (Dominissini et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). It is unclear how the writers and erasers selectively add or remove m6A on RNA sequences. Therefore, the discovery and functional studies of more m6A-related enzymes can help us to understand the mechanism of m6A regulation.

The Main Components of the m6A System: Writers, Erasers, and Readers

Studies on m6A enzymes or novel functions have mainly focused on animal systems, while there have been few studies in plants, especially in crops. In mammals, m6A is produced by a methyltransferase complex consisting of MTase complex comprising methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) (Bokar et al., 1994), wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP) (Agarwala et al., 2012), and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) (Liu et al., 2014) and is removed by the action of the demethylases FTO (Jia et al., 2011) and α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase alkb homolog 5 (ALKBH5) (Zheng et al., 2013). This modification process is dynamic and reversible in the cell. The reader plays a specific regulatory role by recognizing the m6A modification site, which mainly includes the YTH (YT512-BHomology) domain-containing proteins YTHDC1/2 (DC1/2) (Bailey et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2017; Roundtree et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2010) and YTHDF1/2/3 (DF1/2/3) (Dominissini et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014, 2015; Zhou et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2017), HNRNPA2B1 (Agarwala et al., 2012), and eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) (Meyer et al., 2015). However, it should be emphasized that the core enzymes in the m6A system are highly conserved among different species, so studying the regulatory patterns of m6A in animals should also help us to explore its regulation in plants.

Writers

In Arabidopsis, the METTL3 homolog MTA (At4g10760) is highly expressed in seeds, pollen microspores, and meristems. In loss-of-function mutants of T-DNA insertion, an embryonic lethal phenotype and m6A completion loss occur (Craigon et al., 2004). This is consistent with the phenomenon of METTL3 mutation in animals and yeast (Geula et al., 2015). Yeast two-hybrid assay and co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that MTA protein interacts with the protein encoded by FIP37 (At3g54170) in vitro and in vivo (Zhong et al., 2008). FIP37 is a homolog of the selective cleavage protein WTAP in human and Drosophila. FIP37 expression patterns are similar to those of MTA. In addition, disruption of FIP37 by T-DNA insertion also results in an embryonic lethal phenotype with developmental arrest at the globular stage (Vespa et al., 2004; Růžička et al., 2017). MTB is a homolog of human METTL14, which has also been shown to be a part of the m6A methyltransferase complex (Liu et al., 2014). Experiments on RNA interference (RNAi) lines with inducible knockdown of MTB have shown that such knockdown leads to a nearly 50% reduction in m6A levels (Růžička et al., 2017). In addition, using the method of tandem affinity purification (TAP), VIRILIZER (KIAA1429 human homologous protein) (Schwartz et al., 2014) and E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI (HAKAI human homologous protein) were also found to be components of the Arabidopsis methyltransferase complex (Růžička et al., 2017). Inhibition of the expression of VIRILIZER and HAKAI resulted in a decrease in the level of m6A in Arabidopsis mRNA (Růžička et al., 2017). MTA, MTB, FIP37, VIRILIZER, and HAKAI are considered to be the main components of the m6A methyltransferase complexes in Arabidopsis system (Figure 1). In addition, the writers in the m6A system have also been reported in other plants. Knockout of OsFIP or OsMTA2 in rice significantly reduced the level of m6A, while no effect on total m6A levels was observed in the OsMTA1, OsMTA3, and OsMTA4 knockout lines (Zhang et al., 2019). This suggested that OsMTA2 and OsFIP are the main components of the m6A methyltransferase complex in rice (Zhang et al., 2019).

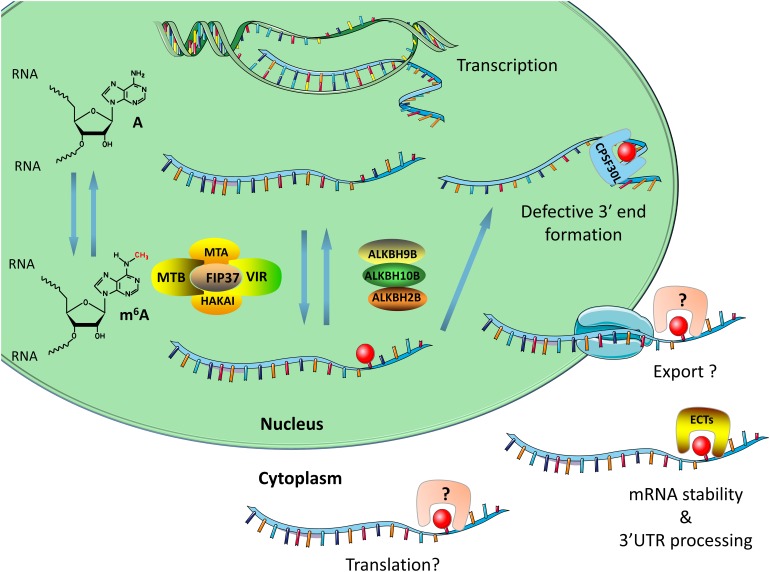

FIGURE 1.

The main components of the m6A system in plants include writers, erasers, and readers. The writers consist of MTA, FIP37, MTB, HAKAI, and VIRILIZER. The demethylases are mainly ALKBH2, ALKBH9B, and ALKBH10B. The m6A binding proteins are mainly ECT family proteins and CPSF30, both of which contain a YTH domain. The writers and erasers are responsible for adding or removing m6A site on RNA. The readers interact with m6A-modified RNA and regulate RNA splicing, RNA stability, and 3′UTR processing. This figure was created using smart Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/).

Erasers

ALKBH9B (At2g17970) and ALKBH10B (At4g02940) have been shown to be active m6A demethylases concerning Arabidopsis system (Duan et al., 2017; Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017). ALKBH9B was the first m6A demethylase reported from Arabidopsis, which enables ssRNA to demethylate m6A in vitro. Moreover, ALKBH9B has a positive effect on viral abundance in plant cells. These findings indicate that methylation status plays an important role in regulating viral infection in Arabidopsis (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017). Duan et al. (2017) also demonstrated that ALKBH10B-mediated demethylation of mRNA m6A affects the mRNA stability of key flowering time regulators, thereby affecting flower turnover. In vitro experiments and those involving transient transformation of tobacco showed that tomato SlALKBH2 can effectively remove m6A modification and reduce the m6A level in vitro and in vivo (Zhou et al., 2019). This indicates that tomato SlALKBH2 has m6A demethylation activity (Zhou et al., 2019).

Readers

The member of the ECT family containing the YTH domain is the most important m6A binding protein in plants (Anderson et al., 2018; Arribas-Hernández et al., 2018; Scutenaire et al., 2018). Scutenaire showed that ECT2 binds to m6A via a tri-tryptophan pocket, and if these amino acids are mutated, ECT2 loses its m6A binding ability (Scutenaire et al., 2018). They also showed that ect mutants share phenotypes (defective trichomes) with mta mutants and FIP37-overexpressing transgenic lines, and the morphological changes in the ect mutant are the result of higher cell ploidy caused by intranuclear replication (Scutenaire et al., 2018), this result was consistent with the phenomenon observed by Arribas-Hernández et al. (2018). In addition, ECT2 improves the stability of m6A methylated RNAs transcribed from genes involved in trichome morphogenesis (Wei et al., 2018). This observation contrasts to the reported decrease in stability of RNAs caused by the binding of YTHDF proteins to this mark in animal systems (Du et al., 2016). However, a previous study by Shen in Arabidopsis found that m6A destabilizes a few transcripts in undifferentiated tissues (Shen et al., 2016). Thus, the mechanisms by which m6A regulates transcript stability have still not been completely clarified in any organism. In a study focused more on the morphological aspects of ECT proteins, including ECT2/3 and 4, it was shown that these proteins are intrinsically important for proper leaf morphogenesis, including trichome branching (Arribas-Hernández et al., 2018).

As described in a recent report, sequence analysis of m6A methyltransferase in 22 plants using Arabidopsis as a model plant revealed that, in higher plants, the number of m6A writers is greater than that in lower plants (Yue et al., 2019). This suggests that higher plants may require more precise mechanisms regulating m6A modification to cope with complex and variable environments (Yue et al., 2019).

Summarizing recent research, we can find that the key component genes of the m6A system are mainly concentrated in meristems and reproductive organs, and lower expression in tissues that stop differentiation and mature (Zhong et al., 2008; Hofmann, 2017; Růžička et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). This suggests that m6A modifications are more likely to occur on actively transcribed genes. Besides, m6A modifications are detected on mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, and sn(o) RNA in plant system (Li et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2015; Anderson et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2020).

Effect of m6A Modification on RNA Function

The above main components of the m6A system above regulate the fate of RNA, by adding, removing, and binding m6A site on RNA. In mammals, m6A modification plays an important role in the regulation of RNA splicing (Liu et al., 2015, 2017; Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016; Pendleton et al., 2017), RNA stability (Wang et al., 2014; Du et al., 2016; Mishima and Tomari, 2016; Huang et al., 2018), RNA export (Roundtree et al., 2017; Edens et al., 2019), 3′ UTR processing (Ke et al., 2015; Bartosovic et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2018; Yue et al., 2018), translation (Zhou et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017), and miRNA processing (Alarcón et al., 2015a, b; Bhat et al., 2019). On the contrary, much less is known about the function of m6A modification regulation of RNA on plant. Our understanding of how the m6A regulated RNA fate is limited to it’s an mRNA stabilizing (Shen et al., 2016; Hofmann, 2017; Wei et al., 2018) or 3′ UTR processing at specific genomic loci (Pontier et al., 2019) mark. The roles in regulating plant RNA export, RNA splicing, and translation remain unexplored. In addition, research on the effect of m6A modification on RNA has mainly focused on genetic interference, and there is no way to accurately predict the effect of m6A modification on RNA at the transcriptome-wide level. Only one or some of the effects of RNA due to changes in m6A modification can be identified.

3′ UTR Processing

In animal systems, m6A modification has been widely reported to regulate mRNA processing including RNA splicing (Liu et al., 2015, 2017; Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016; Pendleton et al., 2017) and 3′ UTR processing (Ke et al., 2015; Bartosovic et al., 2017; Yue et al., 2018). For example, in Drosophila, m6A modification regulates the sex selection process by regulating alternative splicing of the sex determination factor Sex lethal (Sxl) pre-mRNA (Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016); In animal cells, METTL16 regulates the SAM synthetase gene MAT2A splicing process by regulating the m6A modification on MAT2A mRNA, thereby regulating regulate SAM homeostasis (Pendleton et al., 2017). YTH domain-containing protein YTHDC1 regulates the cleavage process by recognizing m6A on mRNA and recruiting the SR protein to its corresponding binding site (Xiao et al., 2016). Therefore, m6A is also considered to be a post-transcriptional regulator of mRNA splicing in animal systems.

In Arabidopsis, the methyltransferase VIRILIZER was found to be co-localized with the splicing factor SR34, but no abnormally spliced transcript was detected in the root of VIRILIZER mutant (Růžička et al., 2017). This suggests that m6A is not involved in large-scale splicing regulation of plant transcripts, which appears to contrast with the findings reported from animals (Xiao et al., 2016). Alternatively, variable splicing regulated by m6A occurs only on specific transcripts or specific tissues, but the level of this is below the limit of detection of the method used for analyzing it.

In mammals, m6A modification regulates alternative poly(A) sites (APA) during 3′ UTR processing (Ke et al., 2015; Bartosovic et al., 2017; Yue et al., 2018). Research by Ke et al. (2015) shows that higher m6A modification in the last exon may affect the usage of APA, while Bartosovic et al. (2017) further shows that m6A modification in the last exon regulates 3′ UTR length by regulating APA. A similar situation was found in plant systems. A recent study showed that the loss of methylation enzyme function of FIP37 resulted in a decrease in m6A modification (Shen et al., 2016) and the pair of spatially adjacent two genes (such as the pair AT4G30570/580 or AT1G71330/340) to form chimeric mRNA (Pontier et al., 2019). The m6A modification can assist in the polyadenylation of the first gene mRNA, thereby limiting mis-splicing to form chimeric mRNA (Pontier et al., 2019). However, this process requires the assistance of F30L, which is a protein comprising the typical m6A recognition protein domain YTH (Figure 1; Pontier et al., 2019). This suggested that the m-ASP (m6A-assisted polyadenylation) pathway ensures transcriptome integrity at rearranged genomic loci in plants (Pontier et al., 2019).

mRNA Stability

How does m6A modification work in plant systems? The most recent report on this issue describes that m6A regulates plant growth and development by affecting mRNA stability. The lack of the Arabidopsis methyltransferase FIP37 results in reduced m6A modification on the mRNA encoded by SAM proliferation-related genes [WUSCHEL (WUS) and SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (STM)], and enhances its stability (Shen et al., 2016). Excessive accumulation of WUS and STM mRNA causes excessive proliferation of SAM (Shen et al., 2016). However, Duan et al. (2017) obtained results that differ from these findings. Specifically, in the functional deletion mutant of Arabidopsis demethylase ALKBH10B, m6A modification on the mRNA encoded by key genes regulating FT, SPL3, and SPL9 was increased, which reduced its stability, accelerated its degradation, and produced a delayed flowering phenotype (Hofmann, 2017). In addition, studies on the m6A reader ECT2 in plants have indicated that it plays an important role in regulating 3′ UTR processing in the nucleus and promoting mRNA stabilization in the cytoplasm (Figure 1; Wei et al., 2018). Loss of function of ECT2 accelerates the degradation of three ECT2-binding mRNAs involved in morphogenesis of the trichome, thereby affecting the branching of the trichome (Wei et al., 2018).

Although m6A modification may stabilize mRNA in plants, no consensus on this issue has yet been reached. In addition, after the modification of methylation of mRNA, m6A binding protein also plays an important role. Moreover, studies on the stability of mRNA by m6A modification have mostly focused on a single mRNA, and cannot explain the effect of m6A modification on mRNA stability across the transcriptome. In summary, m6A may have different effects on mRNA stability in different tissues or organs. It should be emphasized that m6A readers may play precise and complex regulatory roles by recognizing changes in m6A modification on mRNA.

Plant Growth and Development

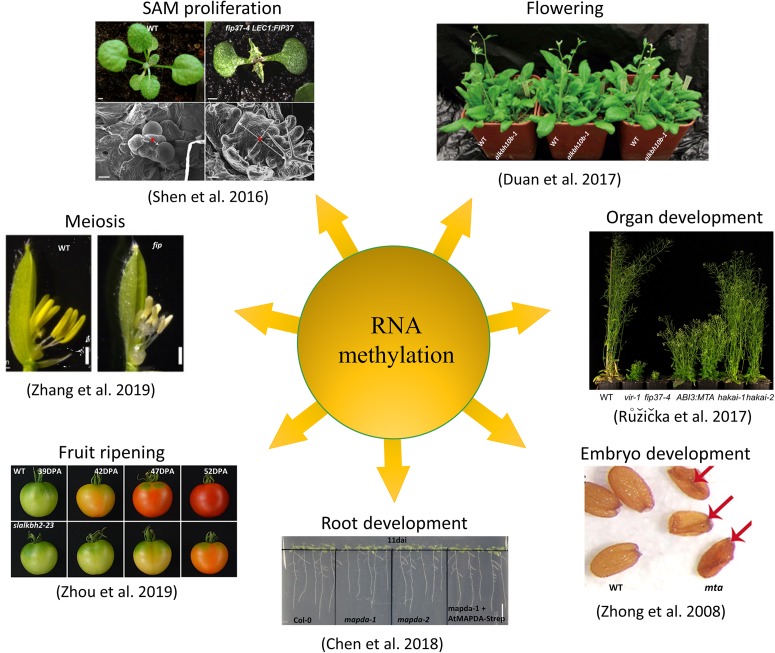

The mechanism of how m6A modification regulates the fate of plant RNA is still unclear. Previous studies have shown that the loss of function of any key component in the m6A system of writers, erasers, or readers can cause disorders in the m6A regulatory system, leading to abnormal growth and development (Figure 2). The lack or reduction of m6A writers, including MTA (Zhong et al., 2008; Anderson et al., 2018), MTB, FIP37 (Vespa et al., 2004), Virilizer (Růžička et al., 2017), and HAKAI (Růžička et al., 2017), results in a significant reduction in the overall level of m6A. This causes phenotypes including embryonic lethality, epidermal hair development abnormality, defective leaf sprouting, and excessive proliferation of vegetative shoot apical meristem. Moreover, loss of function of the eraser ALKBH10B results in leaf dysplasia and a delayed flowering phenotype in Arabidopsis (Hofmann, 2017). Several studies on m6A reader ECT family members have also comprehensively demonstrated the role of ECT protein in regulating Arabidopsis leaf and epidermal hair development (Arribas-Hernández et al., 2018; Scutenaire et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2.

Functions of N6-methyladenosine in plants. In plant systems, m6A modification has been shown to be involved in regulating organ development, SAM proliferation, flowering, meiosis, embryo development, root development, and fruit ripening processes.

In addition, the role of m6A modification in regulating the growth and development of other plants has also begun to be discovered. In rice, the m6A writer OsFIP regulates the development of pollen microspores by directly mediating the addition of m6A to a group of threonine proteases and NTPase mRNA, and regulates its expression and splicing (Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, the complete loss of function of OsFIP leads to a decrease in the level of m6A modification and early degeneration of microspores at the vacuolated pollen stage (Zhang et al., 2019).

Summarizing current studies, we find that the core component of m6A in plant is mainly expressed in meristems, but at low levels in mature tissues and leaves. This suggests that the main regulatory mechanisms of m6A acting on plant growth and development are achieved by adding, removing, or recognizing m6A sites on transcripts that are particularly important for the growth and development of the above-mentioned organs and tissues. In addition, the use of genetic interference methods to study the function of m6A modification will lead to changes in the overall level of m6A modification, and produce unpredictable effects, we need a useful tool to exploring the functions of specific site m6A modifications on RNA.

Function in Biotic Stress Adaptation

Plants have evolved a series of regulatory mechanisms in response to viral infections. These include sRNA (silencing based on small RNA) (Llave, 2010; Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Sharma et al., 2013), DNA methylation (Tirnaz and Batley, 2019), and RNA methylation (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017). In animal systems, m6A modification has been reported to play an important role in regulating viral replication and the viral life cycle (Gokhale et al., 2016; Kennedy et al., 2016; Lichinchi et al., 2016a, b; Tirumuru et al., 2016). However, in plants, with the exception of the smaller group of DNA viruses, most viruses are RNA viruses. RNA viruses are hardly affected by DNA methylation because they do not have DNA during replication. As a widespread modification on RNA, m6A modification may have great potential in regulating plant anti-RNA virus infection.

In the Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutant of alkbh9b, the overall m6A level of viral RNA was found to be increased, and relative to the decrease in viral accumulation in the wild type, its resistance to alfalfa mosaic virus (AMW) was enhanced (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017). It should be emphasized that ALKBH9B does not exhibit the ability to regulate cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) infection. This may be due to the fact that ALKBH9B can interact with the coat protein (CP) of AMV, but not with that of CMV (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017). In addition, in tobacco, the level of m6A modification in tobacco is significantly reduced after infection with TMV (Li et al., 2018). This study suggests that m6A modification may represent a host regulatory mechanism for plants to respond to viral infections. Interestingly, in the genome of several single-stranded RNA plant viruses, ALKB containing a conserved domain has been identified (Bratlie and Drabløs, 2005; Van Den Born et al., 2008). This suggests that some plant viruses have evolved mechanisms to respond to host m6A system regulation.

Abiotic Stress Process

In responding to environmental stress, m6A modification exhibits high sensitivity and complexity in the regulation of responses to heat stress, salt stress, and drought stress. Under salt stress, the m6A system enhances the stability of transcripts by adding m6A sites to salt-tolerant transcripts to regulate the salt tolerance process in Arabidopsis (Anderson et al., 2018). Under drought stress, the expression levels of the maize writer and reader members of the ALKBH10 family and ECT2 family were found to be increased, and the overall level of m6A modification in cells was decreased (Miao et al., 2020). In addition, in different genotypes of maize, m6A modifications were shown to be concentrated on different transcripts. This suggests that m6A modification is involved in the regulation of maize drought resistance and that there are different regulatory mechanisms in different genotypes of maize (Miao et al., 2020). Under heat stress conditions, the Arabidopsis reader ECT2 was found to respond to heat stress and relocate to stress granules (SGs) in the cell (Scutenaire et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018). This process may result in the mRNA that binds to ECT2 relocalizing to stress particles under heat stress. Existing research suggests that the reader regulation of RNA is more direct and rapid than that by adding or erasing m6A sites on RNA, which relies on a writer and eraser. Regulation by a reader can be based on m6A modification on the original mRNA, and it can rapidly regulate the stress signal, especially in regulating short-term stress.

Conclusion and Perspectives

At present, most m6A modification maps in plant systems was drawn by the m6A-seq method. However, there are some limitations to this approach, such as the need for a large number of samples, high requirements for antibody quality, and inability to accurately locate the position of m6A modifications on RNA. Although some improvements have been made to the resolution of m6A-seq, including m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) (Linder et al., 2015), photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A-seq (PA-m6A-seq) (Chen et al., 2015), and m6A-cross-linking immunoprecipitation (m6A-CLIP) (Ke et al., 2015), but these improved methods still have not yet been tested in plants. In addition, m6A modifications are mainly concentrated in meristematic and reproductive organs, suggesting that m6A modifications are more likely to occur on actively transcribed genes. The sample size of these sites is often small, and the m6A-seq methods cannot accurately detect m6A modifications in tissues or cells and perform biological duplication. Therefore, for the development of new m6A detection methods, especially to reduce the sample size and improve detection accuracy, accurate identification of m6A modification at the cellular level is necessary.

Compared with detection methods based on NGS or PCR amplification, the technology of direct detection of m6A modification on RNA, including single-molecule real-time (SMRT) (Vilfan et al., 2013) and single-molecule nanoporous sequencing has great potential. Because PCR amplification is not required, direct detection-based methods do not produce base mismatches and PCR bias, and have the potential to detect multiple types of RNA modification at the same time. And only a lower sample starting amount is required. Ayub et al. have used α-hemolysin (αHL) nanopore sequencing to distinguish between modified and unmodified bases in RNA, including m6A and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) (Ayub and Bayley, 2012). Especially in recent years, nanopore sequencing technology has developed rapidly. Garalde et al. have developed a method for highly parallel direct RNA sequencing on Highly parallel direct RNA sequencing on an array of nanopores (Garalde et al., 2018). Parker et al. used nanopore sequencing technology to map the m6A modification in Arabidopsis thaliana, and revealed the complexity of m6A dynamic modification during mRNA processing (Parker et al., 2020). Therefore, we believe that nanopore sequencing is very suitable for studying small molecule samples and has the potential to accelerate the study of biological functions of modifications on RNA.

The m6A enzyme plays a fundamental role in the m6A regulatory system. However, the number of m6A enzymes found to date in plants is small relative to the number in animals, and no homolog of the major demethylase FTO in animals has been found. Only one demethylase of the ALKBH family was discovered (Hofmann, 2017; Martínez-Pérez et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2019), and it is unclear whether ALKBH family protein can complete the removal of the m6A site on the mRNA. Therefore, it is also very important to find more key components of the m6A system in plants. In addition, it is not clear how writers and erasers selectively add or remove m6A on RNA, which may be related to the special secondary structure of RNA. Cryo-electron microscopy and molecular imaging may help to explore the process of m6A selective modification.

The main way to explore the function of m6A modification is still through genetic interference. However, the impact of adding or removing any key component of the m6A system on plants may be far more than we are concerned about. Therefore, the development of RNA methylation without changing the nucleotide sequence and the overall m6A modification level may be a major development regarding m6A for exploring the m6A function in the future. The CRISPR–Cas9 technology is rapidly evolving and has enabled accurate genome editing, including targeted DNA cleavage, repair, direct base editing, and site-specific epigenome editing. Recently, researchers have used a similar method to fuse m6A writers or erasers with Cas protein, and under the guidance of sgRNA and PAMer, edit the m6A modification on specific mRNA in the cell (Wei and He, 2019). This method of editing m6A did not change the nucleotide sequence and the overall m6A modification level (Wei and He, 2019). This method provides a new tool for studying the biological function of m6A modification and makes it possible to edit m6A at a specific site to improve crop quality.

Author Contributions

HZ and SL prepared the manuscript. NS and XZ conceptualized the idea and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Research Foundation of China (31871538 and U1906204), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD1000700 and 2018YFD1000704), Shandong Province Key Research and Development Program (2019GSF107079), the Development Plan for Youth Innovation Team of Shandong Provincial (2019KJE012), and the Opening Foundation of Shandong Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Ecology and Physiology (SDKL2018008-3).

References

- Agarwala S. D., Blitzblau H. G., Hochwagen A., Fink G. R. (2012). RNA methylation by the MIS complex regulates a cell fate decision in yeast. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002732. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón C. R., Goodarzi H., Lee H., Liu X., Tavazoie S., Tavazoie S. F. (2015a). HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell 162 1299–1308. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón C. R., Lee H., Goodarzi H., Halberg N., Tavazoie S. F. (2015b). N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature 519 482–425. 10.1038/nature14281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. J., Kramer M. C., Gosai S. J., Yu X., Vandivier L. E., Nelson A. D. L., et al. (2018). N6-methyladenosine inhibits local ribonucleolytic cleavage to stabilize mRNAs in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 25 1146.e3–1157.e3. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Hernández L., Bressendorff S., Hansen M. H., Poulsen C., Erdmann S., Brodersen P. (2018). An m6A-YTH module controls developmental timing and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30 952–976. 10.1105/tpc.17.00833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub M., Bayley H. (2012). Individual RNA base recognition in immobilized oligonucleotides using a protein nanopore. Nano Lett. 12 5637–5643. 10.1021/nl3027873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. S., Batista P. J., Gold R. S., Chen Y. G., de Rooij D. G., Chang H. Y., et al. (2017). The conserved RNA helicase YTHDC2 regulates the transition from proliferation to differentiation in the germline. eLife 6:e26116. 10.7554/eLife.26116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosovic M., Molares H. C., Gregorova P., Hrossova D., Kudla G., Vanacova S. (2017). N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 11356–11370. 10.1093/nar/gkx778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S. S., Bielewicz D., Grzelak N., Gulanicz T., Bodi Z., Szewc L., et al. (2019). mRNA adenosine methylase (MTA) deposits m6A on pri-miRNAs to modulate miRNA biogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/557900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi Z., Zhong S., Mehra S., Song J., Li H., Graham N., et al. (2012). Adenosine methylation in Arabidopsis mRNA is associated with the 3′ end and reduced levels cause developmental defects. Front. Plant Sci. 3:48. 10.3389/fpls.2012.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar J. A., Rath-Shambaugh M. E., Ludwiczak R., Narayan P., Rottman F. (1994). Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J. Biol. Chem. 269 17697–17704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratlie M. S., Drabløs F. (2005). Bioinformatic mapping of AlkB homology domains in viruses. BMC Genomics 6:1. 10.1186/1471-2164-6-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Lu Z., Wang X., Fu Y., Luo G. Z., Liu N., et al. (2015). High-resolution N6-methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 1587–1590. 10.1002/anie.201410647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Urs M. J., Sánchez-González I., Olayioye M. A., Herde M., Witte C.-P. (2018). m6A RNA degradation products are catabolized by an evolutionarily conserved N6-Methyl-AMP deaminase in plant and mammalian cells. Plant Cell 30 1511–1522. 10.1105/tpc.18.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Ieong K.-W., Demirci H., Chen J., Petrov A., Prabhakar A., et al. (2016). N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics. Nat. Struc. Mol. Biol. 23 110–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigon D. J., James N., Okyere J., Higgins J., Jotham J., May S. (2004). NASCArrays: a repository for microarray data generated by NASC’s transcriptomics service. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 D575–D577. 10.1093/nar/gkh133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. (1974). Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 71 3971–3975. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., et al. (2012). Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485 201. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., et al. (2016). YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4–NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 7 121–126. 10.1038/ncomms12626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H.-C., Wei L.-H., Zhang C., Wang Y., Chen L., Lu Z., et al. (2017). ALKBH10B is an RNA N6-methyladenosine demethylase affecting Arabidopsis floral transition. Plant Cell 29 2995–3011. 10.1105/tpc.16.00912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens B. M., Vissers C., Su J., Arumugam S., Xu Z., Shi H., et al. (2019). FMRP modulates neural differentiation through m6A-Dependent mRNA Nuclear Export. Cell Rep. 28 845–854. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garalde D. R., Snell E. A., Jachimowicz D., Sipos B., Lloyd J. H., Bruce M., et al. (2018). Highly parallel direct RNA sequencing on an array of nanopores. Nat. Methods 15:201. 10.1038/nmeth.4577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Dominissini D., Mansour A. A., Kol N., Salmon-Divon M., et al. (2015). m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 347 1002–1006. 10.1126/science.1261417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale N. S., McIntyre A. B., McFadden M. J., Roder A. E., Kennedy E. M., Gandara J. A., et al. (2016). N6-methyladenosine in Flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host Microb. 20 654–665. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussmann I. U., Bodi Z., Sanchez-Moran E., Mongan N. P., Archer N., Fray R. G., et al. (2016). m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature 540 301–304. 10.1038/nature20577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann N. R. (2017). Epitranscriptomics and flowering: mRNA methylation/demethylation regulates flowering time. Plant Cell 29 2949–2950. 10.1105/tpc.17.00929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. J., Zhu Y., Ma H., Guo Y., Shi X., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Ythdc2 is an N 6-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 27 1115–1127. 10.1038/cr.2017.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Weng H., Sun W., Qin X., Shi H., Wu H., et al. (2018). Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 20 285–295. 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y., et al. (2011). N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7 885–887. 10.1038/nchembio.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke S., Alemu E. A., Mertens C., Gantman E. C., Fak J. J., Mele A., et al. (2015). A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3′ UTR regulation. Genes Dev. 29 2037–2053. 10.1101/gad.269415.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy E. M., Bogerd H. P., Kornepati A. V., Kang D., Ghoshal D., Marshall J. B., et al. (2016). Posttranscriptional m6A editing of HIV-1 mRNAs enhances viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 19 675–685. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy T. D., Lane B. G. (1979). Wheat embryo ribonucleates. XIII. Methyl-substituted nucleoside constituents and 5′-terminal dinucleotide sequences in bulk poly(A)-rich RNA from imbibing wheat embryos. Can. J. Biochem. 57 927–931. 10.1139/o79-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lence T., Akhtar J., Bayer M., Schmid K., Spindler L., Ho C. H., et al. (2016). m6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature 540 242–247. 10.1038/nature20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Chen Y.-S., Ping X.-L., Yang X., Xiao W., Yang Y., et al. (2017). Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 27 444–447. 10.1038/cr.2017.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang X., Li C., Hu S., Yu J., Song S. (2014). Transcriptome-wide N6-methyladenosine profiling of rice callus and leaf reveals the presence of tissue-specific competitors involved in selective mRNA modification. RNA Biol. 11 1180–1188. 10.4161/rna.36281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Shi J., Yu L., Zhao X., Ran L., Hu D., et al. (2018). N6-methyl-adenosine level in Nicotiana tabacum is associated with tobacco mosaic virus. Virol. J. 15:87. 10.1186/s12985-018-0997-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichinchi G., Gao S., Saletore Y., Gonzalez G. M., Bansal V., Wang Y., et al. (2016a). Dynamics of the human and viral m6A RNA methylomes during HIV-1 infection of T cells. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16011. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichinchi G., Zhao B. S., Wu Y., Lu Z., Qin Y., He C., et al. (2016b). Dynamics of human and viral RNA methylation during Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 20 666–673. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder B., Grozhik A. V., Olarerin-George A. O., Meydan C., Mason C. E., Jaffrey S. R. (2015). Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat. Methods 12 767–772. 10.1038/nmeth.3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yue Y., Han D., Wang X., Fu Y., Zhang L., et al. (2014). A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 93–95. 10.1038/nchembio.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Dai Q., Zheng G., He C., Parisien M., Pan T. (2015). N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 518 560–564. 10.1038/nature14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Zhou K. I., Parisien M., Dai Q., Diatchenko L., Pan T. (2017). N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 6051–6063. 10.1093/nar/gkx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave C. (2010). Virus-derived small interfering RNAs at the core of plant–virus interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 15 701–707. 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G.-Z., MacQueen A., Zheng G., Duan H., Dore L. C., Lu Z., et al. (2014). Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Commun. 5:5630. 10.1038/ncomms6630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Wang Y., Wang M., Zhang L., Peng H., Zhou Y., et al. (2020). Natural variation in RNA m6A methylation and its relationship with translational status. Plant Physiol. 182 332–344. 10.1104/pp.19.00987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pérez M., Aparicio F., López-Gresa M. P., Bellés J. M., Sánchez-Navarro J. A., Pallás V. (2017). Arabidopsis m6A demethylase activity modulates viral infection of a plant virus and the m6A abundance in its genomic RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114:10755. 10.1073/pnas.1703139114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D., Patil D. P., Zhou J., Zinoviev A., Skabkin M. A., Elemento O., et al. (2015). 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell 163 999–1010. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D., Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C. E., Jaffrey S. R. (2012). Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′. UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149 1635–1646. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Z., Zhang T., Qi Y., Song J., Han Z., Ma C. (2020). Evolution of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methylome mediated by genomic duplication. Plant Physiol. 182 345–360. 10.1104/pp.19.00323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y., Tomari Y. (2016). Codon usage and 3′ UTR length determine maternal mRNA stability in zebrafish. Mol. Cell 61 874–885. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J. (1979). N6-methyladenosine in maize poly (A)-containing RNA. Plant Sci. Lett. 15 357–361. 10.1016/0304-4211(79)90141-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M. T., Knop K., Sherwood A. V., Schurch N. J., Mackinnon K., Gould P. D., et al. (2020). Nanopore direct RNA sequencing maps the complexity of Arabidopsis mRNA processing and m6A modification. eLife 9:e49658. 10.7554/eLife.49658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton K. E., Chen B., Liu K., Hunter O. V., Xie Y., Tu B. P., et al. (2017). The U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell 169 824.–835. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontier D., Picart C., El Baidouri M., Roudier F., Xu T., Lahmy S., et al. (2019). The m6A pathway protects the transcriptome integrity by restricting RNA chimera formation in plants. Life Sci. Alliance 2:e201900393. 10.26508/lsa.201900393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumplin N., Voinnet O. (2013). RNA silencing suppression by plant pathogens: defence, counter-defence and counter-counter-defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 745–760. 10.1038/nrmicro3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I. A., Luo G.-Z., Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhou T., Cui Y., et al. (2017). YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. eLife 6:e31311. 10.7554/eLife.31311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Růžička K., Zhang M., Campilho A., Bodi Z., Kashif M., Saleh M., et al. (2017). Identification of factors required for m6A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytol. 215 157–172. 10.1111/nph.14586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler U., Kelley D. E., Perry R. P. (1977). Comparison of methylated sequences in messenger RNA and heterogeneous nuclear RNA from mouse L cells. J. Mol. Biol. 115 695–714. 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90110-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Agarwala S. D., Mumbach M. R., Jovanovic M., Mertins P., Shishkin A., et al. (2013). High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell 155 1409–1421. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Mumbach M. R., Jovanovic M., Wang T., Maciag K., Bushkin G. G., et al. (2014). Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5′ sites. Cell Rep. 8 284–296. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scutenaire J., Deragon J.-M., Jean V., Benhamed M., Raynaud C., Favory J.-J., et al. (2018). The YTH domain protein ECT2 is an m6A Reader required for normal trichome branching in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30 986–1005. 10.1105/tpc.17.00854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N., Sahu P. P., Puranik S., Prasad M. (2013). Recent advances in plant–virus interaction with emphasis on small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Mol. Biotechnol. 55 63–77. 10.1007/s12033-012-9615-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L., Liang Z., Gu X., Chen Y., Teo Z. W. N., Hou X., et al. (2016). N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates shoot stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 38 186–200. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wang X., Lu Z., Zhao B. S., Ma H., Hsu P. J., et al. (2017). YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 27 315–328. 10.1038/cr.2017.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnaz S., Batley J. (2019). DNA methylation: toward crop disease resistance improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 24 1137–1150. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirumuru N., Zhao B. S., Lu W., Lu Z., He C., Wu L. (2016). N6-methyladenosine of HIV-1 RNA regulates viral infection and HIV-1 Gag protein expression. eLife 5:e15528. 10.7554/eLife.15528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Born E., Omelchenko M. V., Bekkelund A., Leihne V., Koonin E. V., Dolja V. V., et al. (2008). Viral AlkB proteins repair RNA damage by oxidative demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 5451–5461. 10.1093/nar/gkn519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa L., Vachon G., Berger F., Perazza D., Faure J.-D., Herzog M. (2004). The immunophilin-interacting protein AtFIP37 from Arabidopsis is essential for plant development and is involved in trichome endoreduplication. Plant Physiol. 134 1283–1292. 10.1104/pp.103.028050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilfan I. D., Tsai Y.-C., Clark T. A., Wegener J., Dai Q., Yi C., et al. (2013). Analysis of RNA base modification and structural rearrangement by single-molecule real-time detection of reverse transcription. J. Nanobiotechnol. 11:8. 10.1186/1477-3155-11-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y., Tang K., Zhang D., Xie S., Zhu X., Wang Z., et al. (2015). Transcriptome-wide high-throughput deep m6A-seq reveals unique differential m6A methylation patterns between three organs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 16:272. 10.1186/s13059-015-0839-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G. C., Yue Y., Han D., et al. (2014). N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., et al. (2015). N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161 1388–1399. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C.-M., Gershowitz A., Moss B. (1975). Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell 4 379–386. 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., He C. (2019). Site-specific m6A editing. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15 848–849. 10.1038/s41589-019-0349-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.-H., Song P., Wang Y., Lu Z., Tang Q., Yu Q., et al. (2018). The m6A Reader ECT2 controls trichome morphology by affecting mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30 968–985. 10.1105/tpc.17.00934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Adhikari S., Dahal U., Chen Y.-S., Hao Y.-J., Sun B.-F., et al. (2016). Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 61 507–519. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue H., Nie X., Yan Z., Weining S. (2019). N6-methyladenosine regulatory machinery in plants: composition, function and evolution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17 1194–1208. 10.1111/pbi.13149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y., Liu J., Cui X., Cao J., Luo G., Zhang Z., et al. (2018). VIRMA mediates preferential m 6 A mRNA methylation in 3′ UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discovery 4 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Zhang Y.-C., Liao J.-Y., Yu Y., Zhou Y.-F., Feng Y.-Z., et al. (2019). The subunit of RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase OsFIP regulates early degeneration of microspores in rice. PLoS Genet. 15:e1008120. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Theler D., Kaminska K. H., Hiller M., de la Grange P., Pudimat R., et al. (2010). The YTH domain is a novel RNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 285 14701–14710. 10.1074/jbc.M110.104711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Dahl J. A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.-M., Li C. J., et al. (2013). ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 49 18–29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Li H., Bodi Z., Button J., Vespa L., Herzog M., et al. (2008). MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell 20 1278–1288. 10.1105/tpc.108.058883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Wan J., Gao X., Zhang X., Jaffrey S. R., Qian S.-B. (2015). Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 526 591–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Tian S., Qin G. (2019). RNA methylomes reveal the m6A-mediated regulation of DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 in tomato fruit ripening. Genome Biol. 20:156. 10.1186/s13059-019-1771-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]