Interventions and small molecules, which promote formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), have repeatedly been shown to increase stress resistance and lifespan of different model organisms. These phenotypes occur only in response to low concentrations of ROS, while higher concentrations exert opposing effects. This non‐linear or hormetic dose–response relationship has been termed mitohormesis, since ROS are mainly generated within the mitochondrial compartment. A report by Matsumura et al in this issue of EMBO Reports now demonstrates that an endogenously formed metabolite, namely N‐acetyl‐L‐tyrosine (NAT), is instrumental in promoting cellular and organismal resilience by inducing mitohormetic mechanisms, likely in an evolutionarily conserved manner [1].

Subject Categories: Metabolism, Molecular Biology of Disease,

Low levels of mitochondria‐derived ROS in response to mild stress have beneficial effects on health‐ and lifespan, a process called mitohormesis. A study in this issue identifies an endogenously formed metabolite, N‐acetyl‐L‐tyrosine (NAT) as an inducer of mitohormetic mechanisms and stress resilience.

Aging is generally defined as the progressive decline in physiological function of an organism over time, resulting in a decrease of its fitness and ultimately death. This process is accompanied by a loss in the ability to uphold or reestablish cellular and systemic homeostasis following continuous endogenous or environmental insults, likely due to the eventual breakdown or overwhelming of a variety of stress response, detoxification, and quality control pathways. Despite their diverse etiology and symptoms, aging is a primary risk factor for the development of several aging‐associated diseases (AADs), such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer's disease, and cancer. Ideally, therapeutic treatment strategies should aim to preemptively boost an organism's capability to deal with diverse stressors and maintain homeostasis, instead of merely treating symptoms of AADs after they have become manifest. Yet, the development of such treatment regimens will require additional research efforts to acquire a better understanding of the biological mechanisms involved.

The concept of mitohormesis provides a mechanistic approach to better delineate the potential benefits and limitations of activating cellular stress response pathways and predicts a common feature that different health‐promoting and lifespan‐extending interventions are likely to share 2. Specifically, mitohormesis posits that mild transient perturbations of mitochondrial function activate a retrograde mitochondria‐to‐nucleus signaling mechanism, which is mediated by an increase in mitochondria‐derived ROS 3. These ROS act on redox‐sensitive transcription factors (TFs), such as NRF2, HSF1, and members of the FOXO family, which in turn can transcriptionally upregulate genes involved in cellular stress response, resulting in a net positive outcome for the organism despite the initial mitochondrial perturbation. The insight that ROS are extensively involved in intracellular signaling, supported by ample experimental evidence over the last decades, has called into question the long‐standing view that they primarily act as damaging agents 4. In recent years, ROS‐dependent mitohormetic mechanisms have been suggested to be responsible for promoting the beneficial physiological effects following interventions such as physical exercise and dietary restriction. In addition, several small‐molecule compounds that were demonstrated to exhibit health‐beneficial and lifespan‐extending effects in different model organisms at low doses function at least in part by inhibiting the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which is known to increase mitochondrial ROS through non‐enzymatic transfer of electrons to molecular oxygen at complex I or III 5. While mitohormesis and in particular the general importance of ROS as mediators of intracellular stress response signaling are well supported by experimental evidence, how exactly various interventions, drugs, and stressors converge on mitochondria as a signaling hub, when, how, and where ROS and possibly other factors relay mitochondrial perturbations, and which effectors, aside from the already known ones, are ultimately responsible for eliciting health‐beneficial effects is not yet understood in detail.

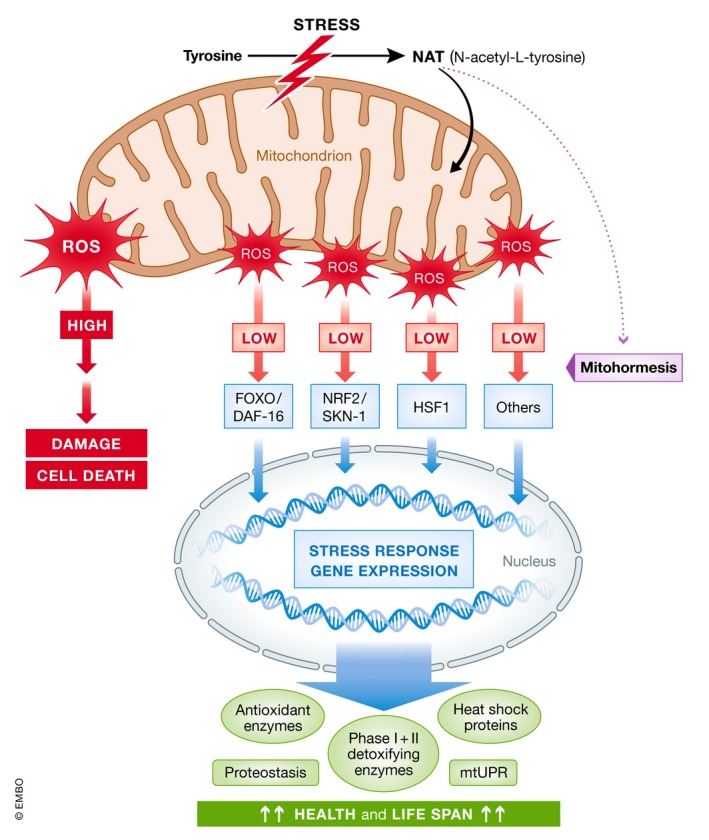

The study by Matsumura et al contributes to a better understanding of mitohormetic processes and lends support to their potential therapeutic utilization by identifying an endogenously formed small metabolite as a resilience‐promoting triggering factor for mitohormesis in stressed animals 1. Based on the observation that armyworms parasitized by wasp larvae, despite the severe burden imposed by the parasitoids, are remarkably resistant to heat stress, the authors identify NAT, present in the hemolymph of the host organism, as the molecule mediating this seemingly paradoxical phenotype. Treatment with NAT is demonstrated to be sufficient to induce tolerance to heat stress in armyworms and other insect species. Interestingly, the study identifies NAT also in human serum and reports an increase in serum of mice subjected to heat and restraint stress, with NAT pretreatment of stressed mice significantly lowering the concentrations of corticosterone and peroxidized lipids, the latter often used as a marker for oxidative stress. In fruit flies, NAT‐induced thermotolerance is found to require the redox‐sensitive TFs NRF2 and FOXO, with NAT treatment increasing the nuclear localization of FOXO and expression of several antioxidant enzymes regulated by this TF. Together with the observations that NAT causes a transient depolarization of mitochondria as well as a weak transient increase in ROS, Matsumura et al conclude that NAT exerts its beneficial effects on stress resistance through mitohormesis (Fig 1).

Figure 1. The endogenous metabolite N‐acetyl‐L‐tyrosine triggers mitohormesis in response to stress.

Mild perturbations of mitochondrial function, leading to an increase in mitochondria‐derived ROS, activate a retrograde mitochondria‐to‐nucleus signaling mechanism, which induces transcription of various genes involved in cellular stress response via redox‐sensitive transcription factors, e.g., FOXO (nematodal DAF‐16), NRF2 (nematodal SKN‐1), and HSF1, a process termed mitohormesis. Matsumura et al identify the endogenous metabolite N‐acetyl‐L‐tyrosine, which is formed in response to stress from its precursor tyrosine, as a triggering factor of mitohormesis in animal cells. mtUPR: mitochondrial unfolded protein response; ROS: reactive oxygen species. Modified from [Ref. 6].

These findings extend evidence derived from the nematodal aging model Caenorhabditis elegans, in which supplementation with tyrosine 7, the likely precursor of NAT, as well as other amino acids, such as proline 8 or the branched‐chain amino acid leucine 9, has previously been shown to increase stress resistance and prolong lifespan. Additionally, interfering with C. elegans threonine catabolism also promotes formation of an endogenous metabolite, namely methylglyoxal, which induces a hormetic response that positively impacts longevity at lower doses, while acting as a toxin at higher concentrations 10.

The conclusions derived from the study of Matsumura et al are intriguing, especially since NAT appears to occur as an endogenous stress‐signaling metabolite not only in insects but also in mammals, potentially even humans. Based on the results, it is indeed probable that NAT, at least in Drosophila, is triggering mitohormesis, i.e., acting on mitochondria to transiently generate ROS, which then serve to activate redox‐sensitive TFs that increase the expression of genes involved in cellular stress response 1. It will now be very interesting to investigate in more detail (i) to what extent the described effects of NAT on mitochondria, ROS, and downstream effectors are conserved and also hold true in other species; (ii) in what way, directly or indirectly, NAT is impacting mitochondrial metabolism, specifically respiratory chain function; (iii) how exactly various stresses cause formation of NAT and whether additional types of stress, e.g., oxidative stress or environmental toxins, also increase NAT levels and can in turn be mitigated by NAT pretreatment; (iv) if there are any general health‐beneficial and potentially lifespan‐extending effects of NAT in different model organisms; (v) and lastly, whether NAT supplementation in humans should thus be considered as a therapeutic strategy to promote overall health.

In summary, Matsumura et al identify an endogenous metabolite capable of promoting mitohormesis to foster resilience and stress adaptation in different species from insects to mammals, supporting further research on targeted interventions to boost endogenous defense mechanisms as a means to extend the healthspan of higher organisms and ultimately humans.

EMBO Reports (2020) 21: e50340

See also: https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201949211 (May 2020)

Contributor Information

Fabian Fischer, Email: fabian-fischer@ethz.ch.

Michael Ristow, Email: michael-ristow@ethz.ch.

References

- 1. Matsumura T, Uryu O, Matsuhisa F et al (2020) EMBO Rep 21: e49211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shadel GS, Horvath TL (2015) Cell 163: 560–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schulz TJ, Zarse K, Voigt A et al (2007) Cell Metab 6: 280–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chandel NS (2015) Cell Metab 22: 204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Haes W, Frooninckx L, Van Assche R et al (2014) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: E2501–E2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ristow M, Schmeisser K (2014) Dose Response 12:288–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Edwards C, Canfield J, Copes N et al (2015) BMC Genet 16: 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zarse K, Schmeisser S, Groth M et al (2012) Cell Metab 15: 451–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mansfeld J, Urban N, Priebe S et al (2015) Nat Commun 6: e10043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ravichandran M, Priebe S, Grigolon G et al (2018) Cell Metab 27: 914–925 e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]