Abstract

National, epidemiological data that provide lifetime rates of psychological, physical, and sexual adolescent data abuse (ADA) perpetration and victimization with in the same sample of youth are lacking. To address this gap, data from 1058 randomly selected U.S. youth, 14–21 years old, surveyed online in 2011 and/or 2012, were weighted to be nationally representative and analyzed. In addition to reporting prevalence rates, we also examined the overlap of the six types of ADA queried. Results suggested that ADA was commonly reported by both male and female youth. Half (51%) of female youth and 43% of male youth reported victimization of at least one of the three types of ADA. Half (50%) of female youth and 35% of male youth reported at least one type of ADA perpetration. More male youth reported sexual ADA perpetration than female youth. More female youth reported perpetration of psychological and physical ADA and more reported psychological victimization than male youth. Rates were similar across race and ethnicity, but increased with age. This increase may have been because older youth spent longer time in relationships than younger youth, or perhaps because older youth were developmentally more likely than younger youth to be in abusive relationships. Many youth reported being both perpetrators and victims and/or involved in multiple forms of ADA across their dating history. Together, these findings suggested that interventions should acknowledge that youth may play multiple roles in abusive dyads. Understanding the overlap among ADA within the same as well as across multiple relationships will be invaluable to future interventions aiming to disrupt and prevent ADA.

Keywords: Teen dating violence, Adolescent dating abuse, Adolescence, Sexual violence

Introduction

Adolescent dating abuse (ADA) is a significant public health issue (Ellis, Crooks, & Wolfe, 2009; Foshee, McNaughton Reyes,&Ennett,2010;Holt&Espelage,2005;Howard&Wang, 2003;Wolitzky-Taylor etal.,2008). Victims are more likely than non-victims to experience depression (Ellis et al., 2009; Holt & Espelage,2005;Howard&Wang,2003;Wolitzky-Tayloretal., 2008) and engage in health-risk behaviors such as substance use, physical fighting, and risky sexual activity (Howard & Wang, 2003). Conversely, female perpetrators are more likely than non-perpetrators to report concurrent, elevated levels of depression, and substance use (Foshee et al., 2010).

Adolescent Dating Abuse Prevalence Rates

National rates of ADA victimization and perpetration are critical to understanding the scope of the problem, as well as to provide benchmarking for the ongoing investigation of the behavior. A review of the literature identified several nationally representative studies of randomly identified youth that reported ADA victimization rates (see Table 1 for methodological information). Psychological ADA is most common, while sexual ADA is least commonly reported. Specific prevalence rate estimates are as follows:

Psychological ADA victimization: An estimated 29% of adolescent females and 28% of adolescent males reported psychological abuse victimization in the past 18 months (Halpern, Oslak, Young, Martin, & Kupper, 2001).

Physical ADA victimization: Between 5 and 13% of female and 7–12% of male youth reported physical ADA victimization in the past year to 18 months (Eaton et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2001; Hamby & Turner, 2013; Kann et al., 2014). Wolitzky-Taylor et al. (2008) found very different rates: 1.2% of 12-to 17-year-old females and 0.4% of same-aged males reported lifetime rates of physical assault by a dating partner.

Sexual ADA victimization: Among 1680 youth, aged 12–17 years, surveyed nationally, Hamby and Turner (2013) reported that 3% of adolescent females and 1% of adolescent males in dating relationships were victims of sexual ADA ever in their lifetime. Among the same age group, Wolitzky-Taylor et al. (2008) found that 0.3% of adolescent males and 1.5% of adolescent females experienced sexual ADA victimization. However, the recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey study of 9th–12th graders across the U.S. found that 14% of high school-aged females and 6% of high school-aged males reported sexual ADA victimization in the past year (Kann et al., 2014).

Table 1.

A description of the sampling methodology and questions asked in other nationally representative ADA surveys

| Sample size | Participant age | Collection time | Sampling frame |

Sampling frame details | Collection method | ADA measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eaton et al. (2012) | 15,425 | Grades 9–12 | September 2010–December 2011 | National | All regular public and private schools with students in at least one of the grades 9–12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The sampling frame was obtained from the Market Data Retrieval (MDR) database, which is based upon data from the Common Core of Data from the National Center for Education Statistics. | Self-administered survey in class |

Physical ADA victimization

|

| Halpem et al. (2001) | 7493 (who reported exclusively heterosexual relationships) | Grades 7–12 | Wave II: April–August 1996 | National | Systematic sampling methods and implicit stratification to ensure that the 80 high schools selected were representative of US schools with respect to: region, urbanicity, size, type, and ethnicity. Eligible high schools included an 11th grade and enrolled more than 30 students. | In-home interview administered via laptop computer; audio computer-assisted self-interview technology was used for sensitive questionnaire content, such as dating violence |

Physical ADA victimization

|

| Hamby and Turner(2013) | 1680 | 12–17 years old | January–May 2008 | National | The majority of the sample (67%) was acquired through RDD from a nationwide sampling of residential telephone numbers that took place between January and May, 2008. The other 33% of the sample was obtained through an oversampling of U.S. telephone exchanges that included 70% or more African American, Hispanic, or low income households. | Telephone |

Physical ADA victimization

|

| Kann et al. (2014) | 13,583 | Grades 9–12 | September 2012–December 2013 | National | All regular public and private schools with students in at least one of the grades 9–12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The sampling frame was obtained from the Market Data Retrieval (MDR) database, which is based upon data from the Common Core of Data from the National Center for Education Statistics. | Self-administered in class |

Physical ADA victimization

|

| Wolitzky-Taylor et al. (2008) | 3614 | 12–17 years old | 2005 | National | A national household probability sample obtained from RDD with an oversample of urban-dwelling adolescents. | Telephone |

Sexual assault

|

Even with significant variations in rates and ages of adolescents studied, these studies suggest that ADA victimization is a pervasive problem that has affected a substantial minority of young people. Nonetheless, the range in national prevalence rates across studies is notable. Reasons for these disparities could include differences in measurements and definitions of ADA, sampling methodologies, observation periods (e.g., lifetime versus past 18 months), and other methodological aspects (e.g., in-person versus online data collection, variations in the ages of participants, although all fall under the NIH definition of adolescent) (National Institutes of Health, 1999). Moreover, given that most studies reported victimization in the past 12–18 months, lifetime rates of ADA victimization are less well reported. Because all of the above studies restricted their samples to those who were dating, population-based rates of ADA involvement are lacking as well. Importantly, too, we were unable to identify literature that examined all three types of ADA victimization within the same study. Thus, these studies likely underestimated the true proportion of youth affected, and the overlaps among these ADA experiences were difficult to discern.

Compared to victimization, our understanding of ADA perpetration rates is wanting. Haynie et al. (2013) reported that, nationally, 31% of 10th graders perpetrated physical and/or verbal ADA in the past 12 months. Although three perpetration items were assessed in Wave 2 of the Add Health study, prevalence rates for perpetration were not reported (Halpern et al., 2001; Halpern, Young, Waller, Martin, & Kupper, 2004). Renner and Whitney (2010) reported perpetration as part of an overall rate of physical ADA involvement as either a perpetrator and/or a victim.

Perpetration rates at the local level were more widely reported, but they still varied significantly, likely because of regional differences in cultural and social norms, socioeconomic status, and other factors related to ADA involvement. For example, prevalence rates for victimization of various types of forced sexual activity or sexual coercion, experienced by female youth within their dating relationships, ranged from 15% (Foshee, 1996) to 58% (Jackson, Cram, & Seymour, 2000). A more complete understanding of the occurrence rates of ADA perpetration among a national sample of male and female youth who are of various ages is warranted.

Overlap in Perpetration and Victimization and Different Forms of Adolescent Dating Abuse

Beyond general prevalence rates, previous methodologies have also left an incomplete understanding of how perpetration and victimization, as well as various forms of ADA, might overlap. In the Add Health survey, one in four young adult couples, aged 18 years and older, reported both physical violence perpetration and victimization at least once in their current relationship (Marcus, 2012). Among older youth who have been in a relationship and experienced some type of intimate partner violence, 54% reported both victimization and perpetration experiences across relationships (Renner & Whitney, 2010). Relatively little is known about whether these overlaps exist for younger youth. Halpern et al. (2001) reported that, among 7500 youth in Grades 7–12 who reported exclusively heterosexual romantic relationships, 12% of young males and 12% of young females reported physical or both physical and psychological victimization. Wolitzky-Taylor et al. (2008) found that, among over 3600 12- to 17-year-olds, 0.6% of males and 2.7% of females were victims of either serious physical or sexual ADA. The number of youth who experienced both versus one type of ADA victimization was not reported. However, data from adult studies suggest that overlaps in abuse are important to examine. For example, data from the Boston Area Community Health survey indicated that 4% of adult males and 8% of adult females had been victims of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse perpetrated by another adult (Chiu et al., 2013). An additional 8% of adult males and 14% of adult females were victims of two types of abuse. It also was noted among these adults that experiencing one type of abuse significantly increased the odds of being a victim of another type of abuse. Given that none of the existing nationally representative studies among youth have reported the overlap among ADA victimization rates, little is known about how these forms of victimization overlap within youth’s lives.

Gaps in the Literature

Although national prevalence estimates of ADA victimization exist, as noted above (Eaton et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2001; Hamby & Turner, 2013; Haynie et al., 2013; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008), a comparable focus on ADA perpetration rates is lacking. Moreover, a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence of youth affected by all forms of ADA is absent. Understanding whether it was a few youth who experience multiple forms of abuse or many youth who experience singular forms has implications for prevention effects—particularly during this pivotal developmental period. Furthermore, many existing studies assessed ADA over a limited time period and restricted their sample to dating youth, precluding population-based estimates critical for public health planning and resource allocation. Finally, few, if any, studies considered how rates might change as adolescents age. Consequently, in the current article, we (1) report national, lifetime prevalence rates of physical, psychological, and sexual ADA victimization and perpetration among all youth as well as by youth characteristics (e.g., age, race), and (2) consider the lifetime interplay among victimization and perpetration experiences of psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence. These noted gaps were addressed using data from the Growing Up with Media study, which included a large sample of male and female youth across a wide range of ages, race and ethnicities, and household income levels. This study was particularly amenable to contributing to the ADA literature because of its methodology: Youth were surveyed online to increase their safety and privacy, thereby increasing the likelihood of self-disclosure (Joinson, 1998, 1999). Because youth chose when and where to complete the survey, the survey experience was less vulnerable to peer or teacher influences that might impact school-based data collection efforts. The sample size, over 1500 youth 14–21 years of age, was large enough to support the examination of rates by key demographic indicators. It also allowed for the mapping of rates as youth aged from middle to late adolescence and young adulthood. Furthermore, the methodology used to collect this large dataset made it possible to apply weights, such that the resulting sample can be considered nationally representative.

Method

The survey protocol for this national longitudinal study was reviewed and approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board for Waves 1–3 and the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board for Waves 4–5. Caregivers provided informed permission for their child’s participation; youth provided informed assent. In both cases, agreement was documented by clicking “I agree” in the online survey.

Participants

Wave 1 data were collected in 2006 with 1586 youth-caregiver pairs. Eligible caregivers were equally or more knowledgeable than other adult household members about the youth’s daily activities. Youth participants were 10–15 years old at baseline, English-reading, living in the household at least 50% of the time, and using the Internet in the last 6 months.

The sample was obtained from the Harris Poll OnlineSM (HPOL) opt-in panel (Harris Interactive), which was a multimillion-member panel of online participants and the largest available database of individual double opt-in participants when the cohort was initially recruited in 2006. Diverse methods were leveraged to identify and recruit potential panelists, including targeted emails sent by online partners to their audiences, trade show presentations, targeted postal mail invitations, TV advertisements, member referrals, and telephone recruitment of targeted populations. HPOL data have consistently been shown to be comparable to data obtained from random digit dialing (RDD) surveys of the general populations, once propensity weighting and appropriate sample weights are applied (Berrens, Bohara, Jenkins-Smith, Silva, & Weimer, 2003; Schonlau et al., 2004; Terhanian, Bremer, Smith, & Thomas, 2000). As expected, the sociodemographic characteristics of HPOL panelists when the cohort was recruited in 2006 were similar to the U.S. general population (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2008).

Data were weighted statistically to reflect the population of adults with children 10–15 years of age in the U.S., according to adult age, sex, race/ethnicity, region, education, household income, and child age and sex using statistics from the U.S. Census (Bureau of Labor Statistics & Bureau of the Census, 2006). Adults were the weighting target because they were the recruitment target. A second weight was applied to adjust for attitudinal and behavioral differences of adults in the online panel versus adults who were recruited in nationally representative RDD cohorts. Items included in the weight were general questions included in all telephone and online surveys conducted by the online panel (e.g., the average number of days per week that one exercises, frequency of buying things online). Accordingly, youth characteristics mirrored those of the national population (Table 2).

Table 2.

A comparison of unweighted and weighted demographic characteristics of the youth sample to the national population in 2006

| Demographic characteristics | Wave 1 (unweighted) (n = 1581) | Wave 1 (weighted) (n = 1581) | U.S. General Population (Bureau of Labor Statistics & Bureau of the Census, 2006; U. S. Census Bureau, 2008) | Wave 4/5 Respondents (weighted) (n = 1058) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years M (SE) | 12.5 (0.04) | 12.6 (0.06) | - | 12.5 (0.07) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male youth | 50% | 51% | 51% | 53% |

| Female youth | 50% | 49% | 49% | 47% |

| Race | ||||

| White | 73% | 71% | 76% | 72% |

| Black or African American | 14% | 14% | 16% | 14% |

| Mixed racial background | 7% | 9% | 3% | 9% |

| All other | 6% | 6% | 5% | 5% |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 13% | 17% | 19% | 16% |

| Household income | ||||

| $24,999 or less | 12% | 12% | 22% | 12% |

| $25K–34,999 | 13% | 12% | 11% | 12% |

| $35K–49,999 | 18% | 18% | 16% | 17% |

| $50K–74,999 | 27% | 23% | 20% | 24% |

| $75K–99,999 | 15% | 17% | 13% | 16% |

| $100K+ | 16% | 18% | 18% | 18% |

Wave4 and Wave5 data were collected online in 2011 and 2012, respectively. Five youth are excluded from the Wave1 sample because they were non-responsive to more than 20% of the survey items

Emails were sent to randomly identified HPOL adult members who reported a child living in their household. To reduce response bias related to a particular topic (e.g., dating violence) (McNutt & Lee, 2000), eligibility was confirmed through a preliminary short survey of general demographic questions. Caregivers taking the short survey were unaware of the possibility of being included in a larger survey. Those who were eligible were then invited to take part in the Growing Up with Media study. Recruitment was balanced on youth sex and age.

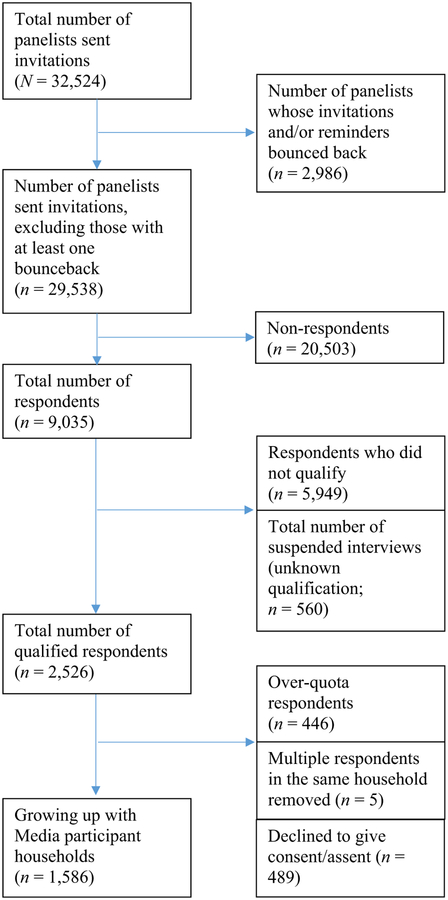

Of the 2526 eligible households identified during the short survey, 63% completed the Wave 1 survey, 18% were eligible but not surveyed because the targeted sample size had been reached, and 19% declined to participate. The stages of recruitment are represented in Fig. 1. Compared to the adults in the cohort, adults of households that declined to participate were significantly older (M = 47.7 years, SD = 0.6 versus M = 44.1 years, SD = 0.3), t(2067) = −6.47, p<.001; more likely to be employed, 56 vs. 50%, χ2 = 5.15, p = .02, and White race, 79 versus 71%, χ2 = 14.28, p<0.001; and less likely to be Hispanic, 7 versus 12%, χ2 = 10.84, p = .001, or of a low income (<$35,000 peryear) household, 19vs. 25%, χ2 = 7.14, p = .008. The groups were equally likely to be married, 73 versus 72%, χ2 = 0.21, p = .65.

Fig. 1.

Growing up with media study disposition

The Wave 1 survey response rate was calculated as the number of qualified participants, plus the number of non-qualified participants, plus the number of participants who started but did not complete the survey, divided by the total number of email invitations sent, minus the number of invitations that bounced back as undeliverable. This rate, 31%, was within the range of well-conducted online surveys at the time (Cook, Heath, & Thompson, 2000).

ADA items were added at Wave 4 and also included in Wave 5. Therefore, the analyses discussed in the current article include only data collected at Wave 4, fielded October 2010–February 2011 with youth aged 13–20 years, and Wave 5, fielded October 2011–March 2012 with youth aged 14–21 years. For these waves, the permission/assent description was updated to mention topics about exposure to sexual, physical, and psychological abuse, among other sensitive subjects (e.g., substance use). The survey included an explanation that their participation and these questions were critical for the research team to understand why some youth have unhealthy relationships. Of the 1586 households who completed the baseline survey, six parents declined, and an additional 63 did not finish the Wave 4 survey before the child could be qualified (i.e., either because the parent did not finish, did not hand the survey to their child, or the child did not complete the qualification process).

Sixty-seven percent of baseline households (n = 1058) completed either the Wave 4 and/or the Wave 5 surveys, of which 71% (n = 750) of youth completed both waves. Characteristics of included participants (i.e., Wave 4, Wave 5, or both Waves completed) were similar to the characteristics of the original sample, suggesting internal validity remained intact (Table 2). For example, 53% of the participating youth in Waves 4 and/or 5 were males, compared to 47% of non-participants, F(1,1582)=1.50, p = .22. Twenty-four percent of participants in Waves 4 and/or 5 reported household incomes of less than $35,000, as did 24% of non-participants, F(1,1582)= 0.01, p = .93.

Caregivers received $20 and youth received $25 as incentives to complete each survey. To increase response rates, an additional $10 was offered in the last month of fielding the survey to youth who had yet to complete the survey.

Measures

Although “teen dating violence” is perhaps the more commonly used phrase, “adolescent” was used in the current study to reflect the broader age range of participants and to mirror the NIH definition of adolescent, which includes youth through age 21 (National Institutes of Health, 1999). “Abuse” was used, rather than violence, to connote a broader range of experiences (i.e., many attribute violence to refer solely to physical acts) (Miller & Levenson, 2013).

For all youth, we deemed their demographic characteristics (e.g., age, household income) at the time of the most recent ADA event to be most important. As such, for youth who reported ADA at Wave 4 but not Wave 5, we used their demographic characteristics at Wave 4, whereas for those who reported ADA at both Wave 4 and 5, we used their Wave 5 demographic data. For youth who did not report ADA, we deemed their most recent report of demographics to be most important and therefore used their Wave 5 data, if available. If not available, we used Wave 4 data.

If ADA was reported in both years, it was only counted once in the prevalence rates. Specifically, among the 750 youth who responded to both waves, the 25% of youth who reported ADA in both waves were counted only once as having experienced victimization and/or perpetration ever in their lifetime.

Youth who reported ever having a romantic relationship were asked subsequent questions about psychological and non-defensive physical ADA victimization and perpetration using items from scales created by Foshee (1996) in a dating violence prevention program for 8th and 9th graders (Foshee et al., 1998). Items were adapted by combining them to result in a shorter scale (e.g., combining pushed, grabbed, kicked, shoved, and hit into one physical abuse item). Adequate internal consistency was reported for these four subscales (i.e., Cronbach’s α>.70 for all but one subscale).

The psychological ADA questions were worded as follows: “Think about all of the people you have been in a romantic relationship with—someone you would call a boyfriend or girlfriend. Which, if any, of the following things has a boyfriend or girlfriend ever done to you? These are things that can happen anywhere, including in-person, on the Internet, and on cell phones or text messaging.” Four psychological ADA victimization items were asked (items shown in Table 3; α = .66).

Table 3.

Lifetime prevalence rates of specific forms of adolescent dating abuse (ADA) perpetration and victimization among 14- to 21-year-olds (n = 1058)

| Form of ADA | All Youth% (n) | Females% (n) | Males% (n) | Effect sizea | d | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victim of psychological ADA | 40.9 (413) | 47.1 (229) | 35.3 (184) | .16 | F(1, 1054) = 6.43 | .01 |

| 1. Would not let you spend time with other people/talk to someone of the opposite sex | 20.7 (211) | 23.6 (119) | 18.0 (92) | .09 | F(1, 1054) = 2.02 | .16 |

| 2. Made you describe where you were every minute of the day | 12.7 (130) | 16.9 (76) | 8.9 (54) | .16 | F(1, 1054) = 6.70 | .01 |

| 3. Did something just to make you jealous | 27.7 (300) | 28.6 (156) | 26.9 (144) | .02 | F(1, 1054) = 0.16 | .69 |

| 4. Put down your looks or said hurtful things in front of others | 7.8 (99) | 11.5 (67) | 4.5 (32) | .21 | F(1, 1054) = 11.34 | <.01 |

| Perpetrator of psychological ADA | 39.2 (420) | 46.3 (242) | 32.9 (178) | .18 | F(1, 1054) = 8.46 | <.01 |

| 1. Would not let your partner spend time with other people/talk to someone of the opposite sex | 17.9 (197) | 18.4 (106) | 17.5 (91) | .02 | F(1, 1054) = 0.06 | .80 |

| 2. Made your partner describe where s/he was every minute of the day | 13.2 (136) | 15.2 (74) | 11.3 (62) | .07 | F(1, 1054) = 1.41 | .23 |

| 3. Did something just to make your partner jealous | 32.1 (341) | 40.5 (202) | 24.5 (139) | .23 | F(1, 1054) = 13.42 | <.01 |

| 4. Put down your partner’s looks or said hurtful things in front of others | 11.8 (128) | 13.0 (71) | 10.7 (57) | .05 | F(1, 1054) = 0.64 | .42 |

| Victim of non-defensive physical ADA | 19.0 (190) | 18.5 (96) | 19.4 (94) | .05 | F(1, 1054) = 0.61 | .81 |

| 1. Pushed, grabbed, kicked, shoved, or hit you | 7.4 (100) | 6.4 (52) | 8.4 (48) | .06 | F(1, 1054) = 0.83 | .36 |

| 2. Threw something at you | 8.1 (89) | 7.6 (39) | 8.5 (50) | .02 | F(1, 1054) = 0.13 | .72 |

| 3. Scratched or slapped you | 9.1 (82) | 6.2 (27) | 11.7 (55) | .11 | F(1, 1054) = 3.41 | .07 |

| 4. Damaged something that belonged to you | 7.3 (71) | 8.0 (40) | 6.6 (31) | .03 | F(1, 1054) = 0.30 | .58 |

| 5. Slammed or held you against a wall | 3.3 (35) | 5.5 (26) | 1.2 (9) | .21 | F(1, 1054) = 11.80 | <.01 |

| 6. Tried to choke you | 1.5 (21) | 2.0 (13) | 1.1 (8) | .07 | F(1, 1054) = 1.20 | .27 |

| 7. Physically twisted or bent your arm or fingers | 4.3 (51) | 5.9 (30) | 2.8 (21) | .11 | F(1, 1054) = 3.06 | .08 |

| Perpetrator of non-defensive physical ADA | 17.3 (165) | 23.0 (107) | 12.1 (58) | .18 | F(1, 1054) = 8.81 | <.01 |

| 1. Pushed, grabbed, kicked, shoved, or hit your partner | 8.2 (85) | 11.4 (55) | 5.3 (30) | .15 | F(1, 1054) = 6.24 | .01 |

| 2. Threw something at your partner | 8.7 (81) | 13.3 (58) | 4.6 (23) | .19 | F(1, 1054) = 9.37 | <.01 |

| 3. Scratched or slapped your partner | 7.1 (72) | 10.4 (60) | 4.1 (12) | .14 | F(1, 1054) = 5.48 | .02 |

| 4. Damaged something that belonged to your partner | 5.0 (52) | 5.7 (25) | 4.5 (27) | .04 | F(1, 1054) = 0.42 | .52 |

| 5. Slammed or held your partner against a wall | 2.0 (22) | 2.0 (10) | 2.0 (12) | .00 | F(1, 1054) = 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 6. Tried to choke your partner | 1.6 (13) | 1.4 (9) | b | F(1, 1054) = 0.13 | ||

| 7. Physically twisted or bent your partner’s arm or fingers | 1.9 (22) | 2.7 (16) | 1.1 (6) | .09 | F(1, 1054) = 1.98 | .16 |

| Victim of sexual ADA | 10.8 (113) | 13.6 (72) | 8.3 (41) | .11 | F(1, 1054) = 3.18 | .08 |

| 1. Your partner kissed, touched, or did something sexual when s/he knew you didn’t want to | 9.2 (96) | 10.9 (58) | 7.7 (38) | .07 | F(1, 1054) = 1.27 | .26 |

| 2. Your partner tried but was not able to make you have sex | 5.6 (58) | 7.1 (43) | 4.1 (15) | .08 | F(1, 1054) = 1.68 | .20 |

| 3. Your partner made you have sex | 2.7 (22) | 3.9 (15) | 1.6 (7) | .09 | F(1, 1054) = 1.95 | .16 |

| Perpetrator of sexual ADA | 3.2 (38) | 1.6 (11) | 4.6 (27) | .12 | F(1, 1054) = 4.05 | .04 |

| 1. Kissed, touched, or did something sexual to your partner when you knew s/he didn’t want you to | 0.6 (7) | b | b | F(1, 1054) = 0.18 | ||

| 2. You tried but were unable to make your partner have sex | 2.5 (28) | 0.4 (6) | 4.4 (22) | .34 | F(1, 1054) = 30.82 | .001 |

| 3. You made your partner have sex | 0.9 (11) | b | 1.0 (7) | F(1, 1054) = 0.01 |

Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012

Effect size is Cohen’s d, which compares rates for females versus males

Not shown because ≤5 observations

Immediately following the victimization questions, parallel perpetration questions were asked (four psychological ADA perpetration items, α = .73). Due to the scope and length of the survey, perpetration was measured as a frequency and victimization as a dichotomous experience. To align the measures, perpetration was reduced to a dichotomous experience. As a result, the relative frequency of both experiences was masked.

Non-defensive physical ADA victimization was introduced thusly: “For this question, again please think about the people you have been in a romantic relationship with—someone you would call a boyfriend or girlfriend. Which, if any, of the following things has a boyfriend or girlfriend ever done to you on purpose? (Only count it if they did it first. Do not count it if they did it in self-defense).” Seven items were presented, as shown in Table 3 (α = .79). Parallel non-defensive perpetration questions were asked immediately following this victimization section (α = .78). Participants were again told not to include self-defensive incidents.

To understand sexual victimization and perpetration more generally, the sexual abuse questions were asked of all youth. The nature of the relationship with the perpetrator was determined in a follow-up question. If the victim or perpetrator was identified as a boyfriend or girlfriend, the experience was categorized as ADA. Three different types of sexual victimization were queried: (1) Has anyone ever kissed, touched, or made you do anything sexual when you did not want to?; (2) Has someone ever tried, but not been able, to make you have sex when you did not want to?; and (3) Has someone ever made you have sex when you did not want to? These items are similar to, but more comprehensive, than the sexual violence item recently added to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey: “kissed, touched, or physically forced to have sexual intercourse when they did not want to” (Kannet al.,2014). Parallel perpetration questions were asked subsequently.

Analyses

“Decline to answer” responses were imputed using single imputation (StataCorp, 2006). To reduce the likelihood of imputing truly non-responsive answers, participants were required to have valid data for at least 80% of the survey questions prior to imputation. As a result, 11 participants were dropped from Wave 4 and 7 were dropped from Wave 5, resulting in a final analytic sample size of 1058 unique youth.

Rates were reported for all youth, dating and non-dating, to provide population-based estimates. Statistical comparisons between ADA experiences and categorical variables were measured using design-based F statistics (i.e., chi-square tests adjusted for survey weighting). Logistic regression equations quantified significant associations.

Results

Eighty percent (n = 827) of youth surveyed had ever had a boyfriend or girlfriend. Although the sex of the partner was not queried, between 3 and 5% of youth in either or both of the two waves reported a non-heterosexual identity (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual) and/or a transgender identity. Unfortunately, subsequent analyses by sexual and gender identity were precluded due to insufficient sample size.

Among all youth, irrespective of dating history, 35% reported both victimization and perpetration, 8% reported perpetration but not victimization, 12% reported victimization but not perpetration, and 46% reported neither victimization nor perpetration. Sixty percent of females self-reported being involved in some form of ADA with a romantic partner: 51% as victims and 50% as perpetrators ever in their lifetime. Forty-nine percent of males reported ADA involvement: 43% as victims and 35% as perpetrators. Females were significantly more likely than males to report ever experiencing psychological ADA victimization (47, 35%;Table 3), Cohen’s d = .16,F(1,1054) = 6.43,p = .01, psychological ADA perpetration (46, 33%), Cohen’s d = .18; F(1,1054) = 8.46, p<.01, and non-defensive physical ADA perpetration (23,12%), Cohen’s d = .18;F(1,1054) = 8.81,p<.01. Males were significantly more likely than females to report sexual ADA perpetration in a romantic relationship as measured by response to at least one of the three sexual abuse items included in the survey (5, 2%), Cohen’s d = .12; F(1, 1054) = 4.05, p = .04.

Twice as many females than males reported experiencing: having their looks put down or having their partner say hurtful things in front of others, being slammed or held against a wall by their partner, and attempted rape (i.e., their partner tried but was not able to make them have sex) by their partner. On the other hand, twice as many males than females reported being scratched or slapped by their partner. In terms of perpetration, more than two times as many females than males reported throwing something at their partner and scratching or slapping their partner, whereas 10 times as many males than females reported attempting to rape their partner.

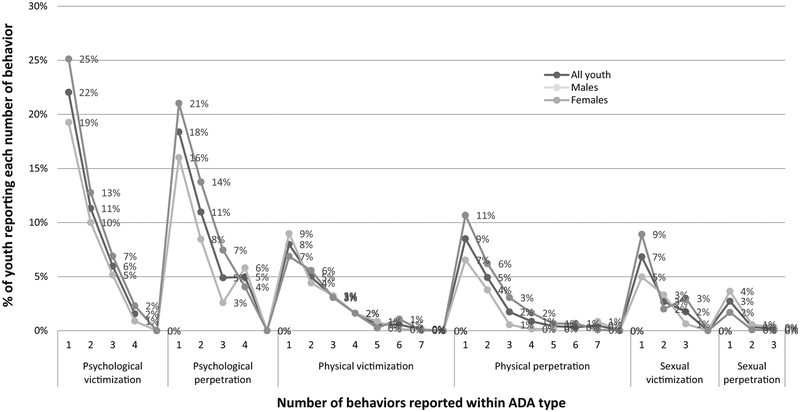

As shown in Fig. 2, most youth who reported ADA experienced or perpetrated only one of the behaviors queried. For example, 22% of all youth (19% of males and 25% of females) reported one of the four types of psychological ADA victimization queried. However, 19% reported between two and four of the behaviors. Similarly, 9% of all youth (7% of males and 11% of females) reported only one of the seven types of physical ADA perpetration queried. Nine percent reported between 2 and 7 of the behaviors. Patterns were similar for males and females.

Fig. 2.

Number of different dating abuse behaviors reported among those who have experienced each type of dating abuse. Percentages reflect the overall sample and can be interpreted as population-based. They do not sum to 100 because youth who reported 0 behaviors are not shown. Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012

Rates of ADA experiences were similar by race and ethnicity, and mostly similar by income (Table 4). Lifetime ADA generally increased by age, with differences noted by sex (Table 5). More than one in four (30%) males reported being both a victim and a perpetrator of at least one type of ADA at some point in their life (not shown in tables), suggesting overlap in abuse-role experiences. Specifically, across the sample, while 26% of males reported being a victim of only one form of ADA, 17% reported being victims of two or all three forms of ADA. Similar rates in type of abuse overlaps were also noted for perpetration. While 24% of males reported perpetrating one form of ADA, 11% reported perpetrating two or all three forms of ADA.

Table 4.

Comparisons of lifetime prevalence rates of adolescent dating abuse (ADA) by youth demographic characteristics among 14- to 21-year-olds (n = 1058)

| Type of ADA | By race | By ethnicity | Household incomea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-white (n = 275) | White (n = 783) | Non-Hispanic (n = 927) | Hispanic (n = 131) | <$35,000 per year (n = 223) | ≥$35,000–<$75,000 per year (n = 528) | ≥$75,000 per year (n = 307) | |

| Psychological ADA | |||||||

| Victimization | 40.2% (102) | 41.2% (311) | 40.5% (359) | 42.7% (54) | 49.9% (106) | 40.3% (189) | 34.7% (118) |

| Perpetration | 34.7% (103) | 41.0% (317) | 38.2% (363) | 44.9% (57) | 40.6% (88) | 36.6% (201) | 41.8% (131) |

| Physical ADA | |||||||

| Victimization | 13.2% (45) | 21.2% (145) | 20.0% (172) | 13.7% (18) | 21.8% (51) | 18.6% (84) | 17.2% (55) |

| Perpetration | 14.0% (41) | 18.5% (124) | 17.1% (145) | 17.9% (20) | 24.3% (49) | 15.6% (68) | 14.1% (48) |

| Sexual ADA | |||||||

| Victimization | 11.1% (30) | 10.6% (83) | 10.0% (100) | 14.6% (13) | 13.7% (26) | 6.3% (43) | 14.7% (44) |

| Perpetration | 2.9% (10) | 3.3% (28) | 3.0% (32) | 3.9% (6) | 2.5% (10) | 3.3% (17) | 3.5% (11) |

No significant differences were noted by race or ethnicity. By household income, sexual ADA victimization varied: low income versus middle income: F(1, 747) = 4.85, p = 0.03, d = 0.18; high income versus middle income: F(1, 831) = 7.10, p = .008, d = 0.19

As reported by caregivers. Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012

Table 5.

Comparisons of lifetime prevalence rates of adolescent dating abuse (ADA) by age and sex among 14- to 21-year-olds (n = 1058)

| Form of ADA | 14- to 15-year-olds | 16- to 17-year-olds | 18- to 21-year-olds | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 196) | (n = 379) | (n = 483) | ||||||||||

| Females (n = 97) | Males (n = 99) | d | p value | Females (n = 188) | Males (n = 191) | d | p value | Females (n = 234) | Males (n = 249) | d | p value | |

| Psychological ADA | ||||||||||||

| Victimization | 33.3% (31) | 24.8% (32) | .13 | .37 | 45.3% (78) | 32.0% (56) | .19 | .07 | 52.1% (120) | 40.9% (96) | .15 | .11 |

| Perpetration | 36.9% (35) | 16.5% (28) | .37 | .01 | 47.6% (81) | 25.6% (49) | .32 | <.01 | 48.1% (126) | 42.7% (101) | .07 | .45 |

| Non-defensive physical ADA | ||||||||||||

| Victimization | 11.6% (13) | 6.5% (11) | .17 | .24 | 10.3% (24) | 14.7% (28) | .09 | .38 | 25.7% (59) | 26.5% (55) | .01 | .90 |

| Perpetration | 7.5% (9) | a | 19.7% (33) | 8.7% (21) | .13 | .03 | 29.5% (65) | 17.1% (32) | .19 | .04 | ||

| Sexual ADA | ||||||||||||

| Victimization | 11.1% (10) | 6.5% (7) | .11 | .45 | 12.3% (26) | 2.6% (10) | .34 | <.01 | 15.1% (36) | 12.4% (24) | .05 | .58 |

| Perpetration | a | a | a | 4.5% (9) | 3.0% (9) | 6.0% (17) | .11 | .24 | ||||

Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012. One 13-year-old was included in the analysis and is incorporated into the ‘14- to 15-year-olds’ column

Not shown because ≤5 observations

High rates of abuse-role overlap were also noted for female youth: 40% reported being both an ADA victim and perpetrator. Overlaps among the three types of abuse were also fairly common. While 26% of females reported being victims of only one form of ADA, a similar percentage, 24%, reported being victims of two or all three forms of ADA. At the same time, while 30% of females reported perpetrating only one form of ADA, 20% of females reported perpetrating two or all three forms of ADA. These numbers reflect the overlap of experiences these youth have had across their existing dating history, regardless of whether or not the experiences occurred in the same dating relationship.

Adjusting for other youth characteristics listed in Table 6, the relative odds of reporting both types of psychological ADA (victimization: aOR = 1.60; perpetration: aOR = 1.90) and physical ADA perpetration (aOR = 2.00) were significantly higher, whereas the relative odds of reporting sexual ADA perpetration (aOR = 0.32) were significantly lower for females (Table 6). In general, the relative odds of all types of ADA increased with age among otherwise similar youth. Number of lifetime partners was positively associated with psychological victimization and perpetration, physical victimization, and sexual perpetration; and negatively associated with sexual perpetration. As expected based upon bivariate comparisons, income, ethnicity, and race did not predict ADA involvement holding all other things equal. Survey process measures were also generally non-significant, with only two exceptions noted.

Table 6.

Relative odds of reporting each type of ADA given youth characteristics

| Youth characteristics | Psychological ADA victimization aOR (95% CI) | Psychological ADA perpetration aOR (95% CI) | Physical ADA victimization aOR (95% CI) | Physical ADA perpetration aOR (95% CI) | Sexual ADA victimization aOR (95% CI) | Sexual ADA perpetration aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 1.60 (1.08, 2.37) | 1.90 (1.29, 2.81) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.41) | 2.00 (1.18, 3.40) | 1.62 (0.91, 2.89) | 0.32 (0.13, 0.77) |

| Age | 1.17 (1.04, 1.31) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) | 1.40 (1.21, 1.60) | 1.34 (1.17, 1.54) | 1.16 (0.98, 1.36) | 1.50 (1.09, 2.05) |

| Income | ||||||

| Low income | 1.00 (RG) | 1.00 (RG) | 1.00 (RG) | 1.00 (RG) | 1.00 (RG) | 1.00 (RG) |

| Middle income | 0.76 (0.46, 1.26) | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) | 0.77 (0.40, 1.46) | 0.58 (0.31, 1.10) | 0.43 (0.20, 0.92) | 0.99 (0.29, 3.33) |

| High income | 0.50 (0.28, 0.88) | 1.04 (0.59, 1.86) | 0.57 (0.29, 1.12) | 0.44 (0.21, 0.92) | 1.09 (0.52, 2.28) | 0.94 (0.24, 3.60) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.08 (0.59, 2.00) | 1.42 (0.80, 2.52) | 0.80 (0.36, 1.76) | 1.38 (0.64, 2.97) | 1.69 (0.74, 3.87) | 1.59 (0.38, 6.75) |

| White race | 1.14 (0.71, 1.83) | 1.46 (0.92, 2.31) | 1.82 (0.96, 3.44) | 1.69 (0.90, 3.17) | 1.08 (0.57, 2.02) | 1.35 (0.35, 5.13) |

| Number of dating partners (lifetime) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.32) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.84) |

| Survey process measures | ||||||

| Dishonesty in answering survey questions | 3.21 (1.45, 7.07) | 2.24(0.82, 6.17) | 1.78 (0.74, 4.29) | 2.43 (0.91, 6.52) | 1.66 (0.63, 4.33) | 7.79 (2.13, 28.50) |

| Not alone when completing the survey | 0.94 (0.63, 1.40) | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) | 1.43 (0.85, 2.43) | 1.52 (0.87, 2.62) | 1.75 (0.92, 3.31) | 1.49 (0.47, 4.65) |

Six multivariate logistic regression models are shown. Each predicts the relative odds of reporting a specific type of ADA given youth characteristics. Odds are adjusted for other characteristics shown on the left side of the table. Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012

RG reference group

Table 7 shows the rates of co-occurrence among different types of ADA. Effect sizes were adjusted for number of lifetime dating partners, sex, age, race, ethnicity, income, honesty in answering survey questions, and being alone or not when taking the survey. For example, the most common overlap was psychological abuse: 28% of youth reported both victimization and perpetration. The relative odds of psychological ADA victimization was 9.5 times higher for youth who reported perpetration compared to otherwise similar youth who did not report perpetration. Although fewer youth reported both non-defensive physical ADA perpetration and victimization (13%), the magnitude of association was the strongest of all pairs of ADA types (aOR = 47.3, p<.001).

Table 7.

The relative odds of one form of adolescent dating abuse (ADA) given the experience of another form of ADA among youth 14–21 years of age (n = 1058)

| Type of ADA | Psychological ADA perpetration | Non-defensive physical ADA victimization | Non-defensive physical ADA perpetration | Sexual ADA victimization | Sexual ADA perpetration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | |

| Psychological ADA victimization | 28.3 | 9.5 (5.8, 15.4) | 15.6 | 10.4 (5.5, 19.6) | 14.2 | 8.8 (4.5, 17.4) | 8.1 | 5.0 (2.5, 10.3) | 2.6 | 9.2 (3.2, 26.4) |

| Psychological ADA perpetration | 14.4 | 7.3 (4.0, 13.3) | 14.6 | 13.1 (6.5, 26.6) | 8.0 | 5.1 (2.5, 10.5) | 2.5 | 7.0 (2.0, 24.2) | ||

| Non-defensive physical ADA victimization | 12.6 | 47.3 (23.4, 95.7) | 3.4 | 2.0 (1.0, 3.9) | 2.1 | 8.5 (3.1, 23.1) | ||||

| Non-defensive physical ADA perpetration | 5.5 | 6.4 (3.2, 12.9) | 2.3 | 19.0 (6.3, 57.4) | ||||||

| Sexual ADA victimization | 1.7 | 13.6 (4.3, 42.6) | ||||||||

Percentages reflect the percent of youth in the sample who reported both types of ADA.Youth are represented in multiple cells if they reported more than two different forms of ADA. OR = odds ratio; reflects the relative odds of reporting the top row (e.g., psychological ADA perpetration) given the left column (e.g., psychological ADA victimization). Effect sizes were adjusted for number of dating partners (lifetime), sex, age, race, ethnicity, income, self-reported honesty, and whether alone or not when completing the survey

Data were collected online in 2011 and 2012

Discussion

In this national study that measured lifetime prevalence rates of psychological, non-defensive physical, and sexual ADA victimization and perpetration among youth spanning middle to late adolescence, findings indicate ADA is a multifaceted phenomena that occurs with substantial frequency in the relationships of U.S. youth. It also appears that an important minority experience multiple behaviors within each type of ADA. Given these findings, next steps should include examination of the frequency of each of these types of episodes within anyone relationship, as well as the number of different relationships that include ADA (e.g., youth who have been in multiple abusive relationships versus one).

Victimization rates for all three forms of ADA were higher in this study than those reported in other national studies (Eaton et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2001; Hamby & Turner, 2013; Kann et al., 2014), perhaps because the current cohort spanned a wider age range, whereas many previous studies have focused on either younger or older youth. Additionally, lifetime rates were assessed in the current study, whereas some previous studies constrained the assessment to the past 12–18 months. Moreover, questions in the current study were not restricted to one particular dating relationship but rather included all previous and current relationships. Also, multiple questions, reflecting a range of experiences from less to more severe were used to assess each type of ADA in the current study, whereas earlier studies have used fewer items to measure each type of ADA. Furthermore, respondents in the current study were prompted to think about experiences in different settings, including in-person, online, on a cell, and via text messaging. To our knowledge, these other national studies have not specified a specific setting. This may have resulted in youth limiting their responses to in-person experiences. The private online data collection strategy may also have resulted in higher rates of self-disclosure—particularly for involvement as a perpetrator, which is likely viewed as socially undesirable or possibly underreported, especially when assessed in the more commonly used school setting strategy.

In the current study, youth reported significant overlap in roles (i.e., perpetration and victimization) and involvement (i.e., the different forms of abuse). Given that these three different types of ADA predicted each other (e.g., psychological ADA victimization was associated with elevated odds of physical ADA perpetration), it would have been impossible for previous studies to disentangle the impact of one type of ADA, particularly if only one form was examined. For example, researchers studying the effects of physical ADA victimization may have also captured the effects of psychological ADA victimization, making it difficult to determine which types of ADA have particularly deleterious effects. To address this issue in the future, researchers may need to assess all types of victimization and perpetration simultaneously.

Differences by sex were noted in the current study. More female youth reported both perpetrating and being victimized by psychological ADA than male youth. They were also more likely than males to report perpetrating non-defensive physical ADA. Interestingly, this disparity in abuse perpetration by sex increased among older youth (Table 3). The issue of gender parity in dating abuse perpetration measures is complex (Hickman, Jaycox, & Aronoff, 2004). Although the results from this and other studies indicate that females engage in relationship abuse at rates either similar to or greater than males (Archer, 2000, 2002), some have argued that female victims acting in self-defense are often miscategorized as perpetrators (Swan, Gambone, Caldwell, Sullivan, & Snow, 2008). A strength of the current study was the explicit question format excluding incidences of self-defense. However, inferences of the other partner’s intent were still required. For example, if a partner hit the participant in reaction to the participant’s verbal threats, the participant could interpret the survey question as victimization experience because the partner hit “first.” It is also important to note that previous research has suggested that females experience greater physical and emotional impacts from ADA victimization than males, including physical injuries (Archer, 2000, 2002; Swahn, Simon, Arias, & Bossarte, 2008), symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (Black et al., 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008), and fearfulness (Black et al., 2011). That is not to say that male victims do not report negative outcomes, as they do (Blacketal., 2011; Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013). As such, it is important to focus on all victims—females and males. Moreover, interventions are likely to be considerably more effective if they acknowledge and adequately address all youth’s roles and experiences.

Findings indicated that sexual ADA perpetration was more commonly reported by males than females. This provides support for interventions that treat unwanted sexual behavior in dating relationships as distinct from other forms of ADA. Nonetheless, females also reported perpetrating sexual ADA. Given the potential negative impacts associated with sexual ADA, including unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections and mental health consequences, efforts to reduce sexual ADA perpetration among all youth are needed.

Given the predominantly heterosexual sample, some might assume that the victimization rates of one sex should generally mirror the perpetration rates for the other sex, yet, in some-cases, there were wide disparities. For example, while 33% of males reported perpetrating psychological ADA, 47% of females reported being victims of psychological ADA. This incongruence may have been because participants were less likely to admit to perpetration than victimization. It may also have been that experiencing victimization was more salient than perpetration and so was easier to remember and report when lifetime rates were queried. Another possible explanation is that perpetrators were more likely to aggress upon multiple partners, resulting in greater victimization rates. Physical perpetration rates may also have been lowered by the explicit instructions to “only count it if they did it first. Do not count it if they did it in self-defense.” This could imply that if someone does not initiate physical violence, then it must be self-defense. This may inadequately capture the concept of self-defense, where someone acts to protect themselves from potential harm. For example, someone might hit or push their partner, and their partner could respond with a violent attack. The second actor may not be acting in self-defense in this scenario but rather retaliatory or more intense physical abuse in response to a partner’s initiation of physical abuse. This is certainly an important area of future inquiry.

Because prevalence rate differences were noted by age, comparing rates generated from studies with various ages of youth participants may lead to disparate findings. In general, rates increased as youth aged in the current study. Older youth may be more likely to engage in dating abuse as part of a developmental trajectory that extends into young adulthood. Because the rates reported here were population-based, it is also possible that the rates were higher for older youth because they had spent more time at risk and because dating becomes more common as youth age. Interpretation of increased rates among older youth should consider these possibilities.

Beyond those mentioned above, the current study had several additional limitations. Recruiting truly nationally representative samples is increasingly difficult (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2012). These difficulties are magnified when recruiting youth for studies that involve sensitive topics. In addition, underlying factors related to self-selection in the online panel may have affected the sample’s generalizability. However, to address this limitation and to minimize self-selection bias, participants were randomly recruited from the four million panel members, and eligibility was determined before describing the study’s purpose, so as not to attract participants with particular experiences. Moreover, these potential underlying differences were adjusted in the weighting scheme, which included attitudinal and behavioral attributes that were weighted to approximate those observed in national samples recruited via RDD (Schonlau et al., 2004; Terhanian et al., 2000).

Due to the scope and length of the survey, a broad range of potentially more and less serious abusive behavior was assessed in each type of ADA. Experiences were not classified a priori by us as more or less severe because this would have required a value judgment that may not reflect the physical or emotional injuries sustained by those involved. Thus, if space allows, future research should include measures of impact to identify those most severely affected by any particular act of abuse.

As a strength, asking about youth’s lifetime ADA experiences led to more comprehensive public health estimates. However, it might have also increased the likelihood of recall bias. For example, some youth may have forgotten about past abuse or characterized the experience differently across time.

Research suggests participants tend to underreport their own violence (Archer, 1999). Perpetration rates might have been even higher if both partners were surveyed. Youth might have been less willing to report perpetration experiences because of social undesirability or privacy concerns. Bell and Naugle (2007) found that indications of social desirability were associated with less endorsement of dating abuse perpetration and victimization experiences for females, but not for males. However, social desirability accounted for less than 10% of variance in the reports.

Conclusions

Taken as a whole, these findings suggest that affected youth, both male and female, are likely to experience many forms of ADA (i.e., psychological, physical, sexual), and many have experienced both perpetration and victimization roles. Although existing ADA prevention programs have affected attitudes and norms, affecting actual perpetration rates has proved difficult (De La Rue, Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2016; Fellmeth, Heffernan, Nurse, Habibula, & Sethi, 2013; Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012). Results of this study reinforce the need for comprehensive prevention programs that address all forms of ADA and that begin early, with youth as young as 14 years of age, and extend throughout adolescence. Future research could give attention to bidirectional violence, common pathways, interchanging roles, and shared risk factors across forms of ADA for both male and female youth. Collecting comprehensive ADA data in samples that are nationally representative will continue to be invaluable for effective prevention and intervention efforts with male and female U.S. youth.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant number 5R0 1CE001543 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We would like to thank the entire study team from the Center for Innovative Public Health Research (formerly Internet Solutions for Kids), Harris Interactive, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. We thank the families for their time and willingness to participate in this study, Dr. Kathleen Basile for her substantial contributions to earlier drafts, and Ms. Emilie Chen for her contributions to the final draft. An abstract of this paper was presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, 2013.

References

- Archer J (1999). Assessment of the reliability of the Conflict Tactics Scales: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14, 1263–1289. doi: 10.1177/088626099014012003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J (2002). Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7, 313–351. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.126.5.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, & Naugle AE (2007). Effects of social desirability on students’ self-reporting of partner abuse perpetration and victimization. Violence and Victims, 22, 243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrens RP, Bohara AK, Jenkins-Smith H, Silva C, & Weimer DL (2003). The advent of Internet surveys for political research: A comparison of telephone and Internet samples. Political Analysis, 11, 1–22. doi: 10.1093/pan/11.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT,…Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics & Bureau of the Census. (2006). Current Population Survey. Retrieved July 5, 2006, from http://www.census.gov/cps/.

- Chiu G, Lutfey K, Litman H, Link C, Hall S, & McKinlay J (2013). Prevalence and overlap of childhood and adult physical, sexual, and emotional abuse: A descriptive analysis of results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Violence and Victims, 28, 381–402. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.11-043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C, Heath F, & Thompson RL (2000). A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or Internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 821–836. doi: 10.1177/00131640021970934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rue L, Polanin JR, Espelage DL, & Pigott TD (2016). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research. doi: 10.3102/0034654316632061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, … Wechsler H (2012). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2011. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(04), 1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Crooks CV, & Wolfe DA (2009). Relational aggression in peer and dating relationships: Links to psychological and behavioral adjustment. Social Development, 18, 253–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, & Rothman E (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131,7178. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellmeth GL, Heffernan C, Nurse J, Habibula S, & Sethi D (2013). Educational and skills-based interventions for preventing relationship and dating violence in adolescents and young adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD004534. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004534.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA (1996). Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Education Research, 11, 275–286. doi: 10.1093/her/11.3.275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman K, Arriaga X, Helms R, Koch G, & Linder G (1998). An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, & Ennett ST (2010). Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Mal-treatment & Trauma, 19, 492–516. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, & Kupper LL (2001). Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationships: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Young ML, Waller MW, Martin SL, & Kupper LL (2004). Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, & Turner H (2013). Measuring teen dating violence in males and females: Insights from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. Psychology of Violence, 3, 323–339. doi: 10.1037/a0029706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, & Iannotti RJ (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U.S. adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, & Aronoff J (2004). Dating violence among adolescents: Prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma Violence Abuse,5, 123–142. doi: 10.1177/1524838003262332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, & Espelage DL (2005).Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review, 34, 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, & Wang MQ (2003). Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent boys’ reports of dating violence. Adolescence, 38, 519–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SM, Cram F, & Seymour FW (2000). Violence and sexual coercion in highschool students’ dating relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 15, 23–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1007545302987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joinson A (1998). Causes and implications of disinhibited behaviors on the Internet In Gackenbach J (Ed.), Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal implications (pp. 43–58). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joinson A (1999). Social desirability, anonymity, and Internet-based questionnaires. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA,…Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.(2014).Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2013.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(Suppl. 4), 1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, & Capaldi D (2012). Clearly we’ve only just begun: Developing effective prevention programs for intimate partner violence. Prevention Science, 13, 410–414. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF (2012).Patterns of intimate partner violence in young adult couples: Nonviolent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent couples. Violence and Victims, 27, 299–314. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.27.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt LA, & Lee R (2000). Intimate partner violence prevalence estimation using telephone surveys: Understanding the effect of non-response bias. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152, 438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, & Levenson R (2013). Hanging out or hooking up: Clinical guidelines on responding to adolescent relationship abuse (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Futures Without Violence. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health.(1999,March17).Frequently asked questions. Inclusion of children as participants in research involving human subjects. Retrieved February 4, 2016, from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/children/pol_children_qa.htm#2590.

- Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. (2012). Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Renner L, & Whitney S(2010).Examining symmetry inintimate partner violence among young adults using socio-demographic characteristics. Journal of Family Violence, 25,91–106. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9273-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Interactive. Harris Poll OnlineSM Panel. Retrieved March 1, 2012, from http://www.harrisinteractive.com/MethodsTools/DataCollection/HarrisPollOnlinePanel.aspx.

- Schonlau M, Zapert K, Simon LP, Sanstad KH, Marcus SM, Adams J, … Berry SH (2004). A comparison between response from a propensity-weighted web survey and an identical RDD survey.Social Science Computer Review, 22, 128–138. doi: 10.1177/0894439303256551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2006). Stata statistical software (Release 9.0). College Station, TX: Stata Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Simon TR, Arias I, & Bossarte RM (2008). Measuring sex differences in violence victimization and perpetration within date and same-sex peer relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1120–1138. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, & Snow DL (2008). A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence and Victims, 23, 301–314. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhanian G, Bremer J, Smith R, & Thomas R (2000). Correcting data from online surveys for the effects of nonrandom selection and nonrandom assignment. Rochester, NY: Harris Interactive. [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. (2008). The 2008 Statistical Abstract of the United States. Retrieved September 23, 2005, from https://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/08abstract/pop.pdf.

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero KJ, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW,…Kilpatrick DG (2008). Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Childand Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 755–762. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, & Mitchell KJ (2008). How risky are social networking sites? A comparison of places online where youth sexual solicitation and harassment occurs. Pediatrics, 121(2), e350–e357. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]