Abstract

A randomized, controlled, double-masked clinical trial was conducted with a combination antiviral-antimediator treatment for experimental rhinovirus colds. In all, 150 healthy men and women (aged 18–51 years) were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: intranasal interferon (IFN)–α2b (6×106 U every 12 h × 3) plus oral chlorpheniramine (12 mg extended release) and ibuprofen (400 mg) every 12 h for 4.5 days (n=59 subjects); intranasal placebo plus oral chlorpheniramine and ibuprofen (n=61 subjects); or intranasal and oral placebos (n=30 subjects). Treatment was started 24 h after intranasal viral challenge. During the 4.5 days of treatment with IFN-α2b, chlorpheniramine, and ibuprofen, the daily mean total symptom score was reduced by 33%–73%, compared with placebo. Treatment reduced the severity of rhinorrhea, sneezing, nasal obstruction, sore throat, cough, and headache and reduced nasal mucus production, nasal tissue use, and virus concentrations in nasal secretions. IFN-α2b added to the effectiveness of chlorpheniramine and ibuprofen and was well tolerated

Effective treatment for the common cold has been an elusive goal. The often-expressed idea of finding a “cure” for the common cold implies the hope of discovering a single molecule for the purpose. Because of this belief, people have been ready to embrace simplistic approaches to cold treatment, such as vitamin C and zinc. However, scientific evidence suggests that the pathogenesis of colds is complex and that cold symptoms result from the action of multiple inflammatory pathways [1]. Commercial cold treatments based on the single-molecule approach, such as decongestants, first-generation antihistamines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), do not block all these pathways and so are effective against some cold symptoms but not others [2]. Antivirals are effective in reducing viral replication and in preventing illness, when given before symptom onset, but have less than an optimal therapeutic effect in reducing symptoms if initiated after illness is present [3–5]. This may be due to their failure to suppress inflammatory events that are activated early in the infection. For a nonantiviral single-molecule cold treatment to work effectively, it must block a putative host response that triggers the humoral, cellular, and neurologic pathways involved in the pathogenesis of cold symptoms [1]. It is not clear that a single triggering event actually exists

An alternative to the single-molecule approach to treating colds is to use a combination therapy that includes an antiviral and ⩾1 anti-inflammatory components that block both viral replication and inflammatory events. The results of an earlier small clinical trial using this type of combination treatment were promising [6]. The current study was conducted to further evaluate the combination treatment approach. Intranasal interferon (IFN)–α2b was used as the antiviral agent because of its activity against rhinovirus, coronavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus and its prolonged duration of action, which allows infrequent dosing [4, 7–9]. It was expected that the IFN-α2b would reduce viral replication, as reflected by virus concentrations in nasal secretions, as was observed in earlier studies [4, 6]. There were 2 anti-inflammatory components. A first-generation antihistamine, chlorpheniramine, was used because of the effectiveness of this class of compounds in treating the sneezing and rhinorrhea of colds [10–13]. It is possible that chlorpheniramine may also have some antitussive activity, because a closely related compound, brompheniramine, has therapeutic activity for cough [13]. An NSAID, ibuprofen, was used because of its effectiveness in treating headache, malaise, and myalgia [14] and because NSAIDs are also effective in treating sore throat [15] and cough [16–18]. It was anticipated that this combination of antiviral and antiinflammatory ingredients, through additive or synergistic action, would treat the full range of cold symptoms, which single-ingredient cold treatments do not [2]

We studied 3 groups in the rhinovirus challenge model. One group received the full treatment, 1 received placebo nose drops and the 2 anti-inflammatory medications, and 1 received placebo nose drops and placebo oral medications

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Population and virus inoculumSubjects were men and women in good health (aged 18–51 years). All had a screening serum neutralizing antibody titer of ⩽2 to type 39 rhinovirus and normal nasal examination results. Women had negative urine pregnancy tests. Exclusion criteria were cold symptoms in the 2 weeks before virus challenge; history of allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, chronic sinusitis, or chronic lung disease; and allergy to the study medications. Subjects received, in coarse drops into the nose, 0.5 mL (0.25 mL/nostril) of a pool containing 30–300 TCID50 of rhinovirus type 39. The inoculation was repeated after ∼20 min

Treatment and placeboIntranasal treatment consisted of IFN-α2b powder (INTRON A) (Schering) dissolved in PBS containing 0.2% potassium sorbate, 2% glycerin, and 1% human albumin. Intranasal placebo was PBS containing the same ingredients but without IFN. Intranasal medication, which contained 3×106 U of IFN (total, 6×106 U/dose) or placebo, was administered in coarse drops at a volume of 0.2 mL per nostril. Oral medications were commercial ibuprofen (400 mg) and chlorpheniramine maleate (12-mg sustained-release ts). Both tablets were placed in an opaque capsule filled with cornstarch. Oral placebo (cornstarch) was placed in an identical capsule. Study nurses administered the medications and supervised immediate ingestion of capsules

Measurement of infectionInfection was determined by daily culture of nasal washes in human embryonic lung cells (WI-38) and measurement of pre- and 21-day postchallenge serum homotypic neutralizing antibody levels. One virus isolate per subject was identified as type 39 rhinovirus [19]. Infection was judged to have occurred if the subject shed type 39 rhinovirus for ⩾1 day and/or if there was a ⩾4-fold increase in homotypic antibody level. Infectivity titrations were done on specimens that were positive for type 39 rhinovirus

Illness measurement Symptom data were collected in double-blind fashion. The occurrence and severity (absent, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; severe, 3; very severe, 4) of sneezing, runny nose, nasal obstruction, sore throat, cough, headache, malaise, and chilliness were recorded between 6 and 8 a.m for 5 days after virus inoculation. Illness was diagnosed when a subject had rhinorrhea and a total symptom score ⩾6 on ⩾3 days and/or the subjective impression of having had a cold [20]. Nasal mucus weights were determined for 24-h periods [10]

Side effects and safetySymptoms of nasal irritation, nasal dryness, blood-tinged nasal mucus, and any other complaints were recorded for all subjects. Nasal examinations were performed by anterior rhinoscopy before and at the end of treatment

Experimental designThe study was conducted twice (9 October 1998 and 13 January 1999), using the same protocol, as a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical trial. Eighty subjects were enrolled in the first trial and 70 in the second. Viral challenge was done between 6:30 and 8 a.m (day 0). Treatment was started 24 h later (day 1), by which time the subjects had developed symptoms. Subjects were placed in individual motel rooms at 5 p.m on day 0 and had contact only with study personnel until the morning of day 5

Three groups were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to the following drugs or placebo: intranasal IFN plus oral chlorpheniramine and ibuprofen, intranasal placebo plus oral chlorpheniramine and ibuprofen, or intranasal placebo plus oral placebo. Intranasal IFN or placebo was given the morning of day 1, the evening of day 1, and the morning of day 2 at 12-h intervals for 3 treatments in total. Oral medication or placebo was started at the same time as IFN and was given every 12 h for 4.5 days

Statistical calculationsThe rhinovirus challenge model was used in a number of earlier published clinical trials [4–6, 11, 13]. In those studies, probability testing was usually done with Student’s t test to evaluate the difference in daily mean symptom scores of infected subjects in the treated and placebo groups. This presents problems that go against good statistical practice. First, the intent-to-treat principle (and randomization) is compromised, since the results are analyzed only from infected and not from all virus-challenged subjects. Second, repeated measurements from the same person are in the data set. These measurements are correlated, and the statistical analysis must reflect this if valid inference is to be drawn. Finally, the severity of each patient’s illness at the start of treatment influences the individual’s response to treatment. Therefore, the severity of the patient’s symptoms at the start of treatment must be taken into consideration in the data analysis. The statistical methods used in the current study were designed to effectively deal with these problems

All the data analyses were carried out on an intent-to-treat population comprising the 150 subjects who were challenged with type 39 rhinovirus. This group included 10 subjects infected with wild virus before viral challenge (3 full treatment, 5 partial treatment, 2 placebo), 9 subjects who did not become infected with the challenge virus (4 full treatment, 4 partial treatment, 1 placebo), 8 infected subjects in the placebo group who did not develop illness during the course of the study, and 6 infected subjects who were asymptomatic when treatment began. The daily symptom severity scores for each individual symptom and for total symptom severity scores and the total number of nasal tissues used over the final 4 days of the study were analyzed as discrete counts. The nasal mucus weights and the virus titer data were analyzed as continuous data

The symptom severity score data were analyzed by generalized estimating equations (GEEs), a modeling technique that is designed for longitudinal data analysis [21]. A negative binomial generalized linear model was utilized to estimate the GEE model parameters for the marginal fixed effects. The model specification included parameters to estimate the effect of the treatment, the effect of time, and the effect of treatment by time interaction. Covariate parameters were also included to adjust for the level of the severity of the subject’s baseline symptoms just before the time when the treatment phase of the study began

We analyzed 2-way and 3-way interaction, with respect to the baseline symptom score and treatment and the baseline symptom score and time, by a generalized Wald test, to determine whether the equal slope assumption was valid. When the equal slope assumption was rejected at the P⩽.05 level, the baseline-adjusted mean for the symptom severity score was estimated at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the baseline symptom severity score empirical distribution. To account for the within-subject serial correlation, the model variance-covariance parameters were estimated by use of the Huber and White sandwich estimator [22]. Confidence interval (CI) construction was based on the Wald normal approximation

Likewise, we modeled the virus titer data by GEE. A γ generalized linear model with a log-link function was utilized to estimate the marginal fixed effects. The data for the total nasal tissue count from days 2 through 5 were modeled with a generalized linear model. The distribution family was specified as negative binomial, and a log-link function was utilized. We also analyzed the data for the total nasal mucus weight from days 2 through 5 by a generalized linear model. The distribution family was specified as γ, and a log-link function was used

We present the statistical comparisons from the symptom severity score analyses as a ratio of the baseline-adjusted mean score and the statistical comparisons from the tissue count analysis as a ratio of the baseline-adjusted mean nasal tissue count. The statistical comparisons of nasal mucus weight and virus titer are shown as the ratio of the baseline-adjusted mean. All statistical computations were done with the PROC GENMOD procedure (version 8.2; SAS Institute software)

Results

Study Population

Of the 150 subjects challenged with virus, 59 (39%) were men and 91 (61%) were women. By race, 106 (71%) were white, 22 (15%) black, 12 (8%) Asian, 7 (5%) Hispanic, and 3 (2%) other. The mean (±SE) age was 21.3±4.8 years (range, 18–51). Fifty-nine subjects received full treatment; 61, partial treatment; and 30, placebo. All medications were taken by all subjects, except for 1 person who missed the second oral dose because of malaise and 7 who missed the last oral dose (6 because of drowsiness, 1 because of malaise)

Infection and Illness Rates

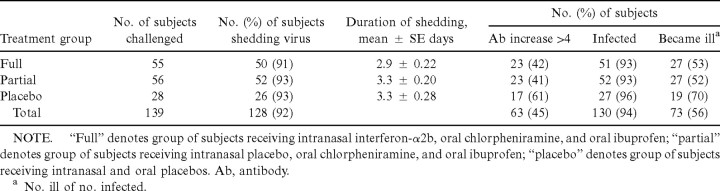

The data from October 1998 and January 1999 were combined. Of the 150 subjects challenged with virus, 139 had a prechallenge antibody titer ⩽2 and did not have a wild virus in their nasal secretions at the time of challenge. Of these 139 subjects, 128 (92%) shed type 39 rhinovirus and 63 (45%) had a homotypic antibody level increase, resulting in 130 (93.5%) who were infected (table 1). The percentage infected was similar in the 3 treatment groups. Illness rates were 53% and 48% in the fully and partially treated groups, respectively, and 70% in the placebo group (P=.2, full vs. placebo; P=.1, partial vs. placebo). The mean (±SE) duration of viral shedding was 2.9±2.2 days in the full treatment versus 3.3±0.20 and 3.3±0.28 in the partial treatment and placebo groups, respectively (full vs. partial treatment, P=.2; full treatment vs. placebo, P=.3)

Table 1.

Infection and illness rates in 139 antibody-free (⩽2) volunteers who were not infected with wild rhinovirus before challenge

Primary Efficacy End Point: Total Symptom Score

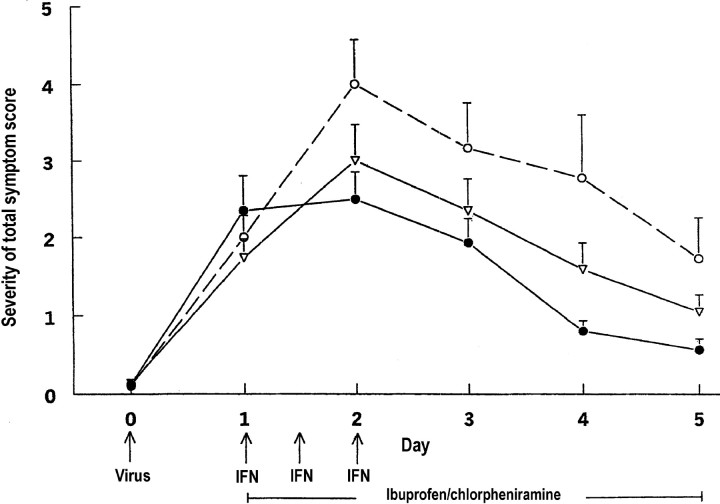

The mean (±SE) total symptom scores were similar among the 3 study arms at 24 h after virus challenge, the time when treatment was initiated (figure 1). The baseline mean (±SE) total symptom score was 2.34±0.45 for subjects who received both the antiviral and the anti-inflammatory medications, 1.74±0.24 for those who received only the anti-inflammatory medication, and 2.00±0.27 for those who received the placebo

Figure 1.

Severity of mean (+SE) total symptom scores in adults with rhinovirus colds, by treatment group (•, intranasal interferon [IFN], oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=59 subjects; ▿, intranasal placebo, oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=61 subjects; ○, intranasal and oral placebos, n=30 subjects)

The severity of the subjects’ symptoms before treatment influenced the subsequent impact that the antiviral and anti-inflammatory medications had on reducing the symptoms over the 4.5 days of treatment (test for baseline total symptom score by study arm interaction, P<.001). Therefore, the model-based adjusted means for the total symptom severity score on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 were estimated at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the day 1 total symptom score empirical distribution. The total symptom scores 0, 1.5, and 3.0 correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and represent baseline symptom scores that are consistent with those of subjects who began treatment with no symptoms, with mild symptoms, and with moderate symptoms

Table 2 shows the adjusted estimates for the treatment effect on days 2–5. For the subjects who received both the antiviral and the anti-inflammatory medications, the treatment effect was more pronounced when the subject began treatment with either mild or moderate symptoms than it was when treatment was started when there were no cold symptoms. Conversely, for those who received only the anti-inflammatory medication, the treatment effect was more pronounced for the subjects who had no symptoms or had mild symptoms at the time the treatment phase of the study began

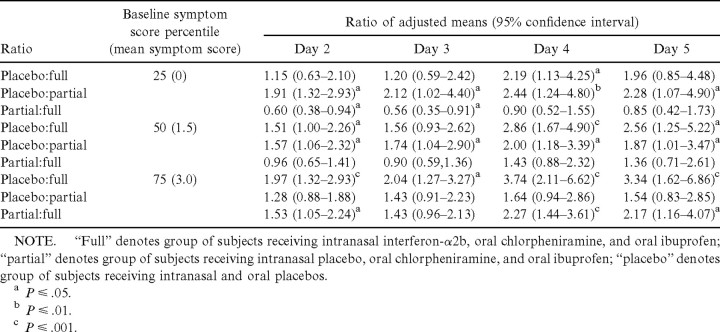

Table 2.

Comparisons between baseline-adjusted mean total daily symptom scores, days 2–5

As shown above, the major impact of the full treatment occurred during the first day of administration. However, the treatment effect also persisted over the days that followed the time of peak symptoms (day 2). For the group of subjects who received both the antiviral and anti-inflammatory medications, the adjusted mean total symptom score was reduced by 22.2% (95% CI, 0.05%–36.4%; P=.014) on day 3, by 67.4% (95% CI, 56.9%–75.4%; P<.001) on day 4, and by 76.2% (95% CI, 60.6%–85.7%; P<.100) on day 5, relative to the adjusted mean total symptom score for the group on day 2, when the mean total symptom score was at its maximum. For the subjects given only anti-inflammatory medication, the adjusted mean total symptom score was reduced by 27.3% (95% CI, 10.8%–40.7%; P=.002) on day 3, by 51.5% (95% CI, 35.7%–63.4%; P<.001) on day 4, and by 66.3% (95% CI, 56.0%–74.2%; P<.001) on day 5, relative to the adjusted mean total symptom score for the group on day 2. Within the placebo arm, the adjusted mean total symptom score was reduced by 19.3% (95% CI, −9.1% through 40.4%; P=.2) on day 3, by 38.1% (95% CI, 9.1%–57.9%; P=.01) on day 4, and by 59.7% (95% CI, 38.5%–73.6%; P<.001) on day 5, relative to the adjusted mean total symptom score for the group on day 2

The decline in the adjusted total symptom score during days 2–5 was more pronounced for the subject group who received the full treatment than for the group given the placebo (P=.03). The adjusted total symptom score declined at a faster rate for the group given full treatment than for the group given only the anti-inflammatory medication (P=.08), whereas the rate of decline in the adjusted total symptom score was similar for those who received placebo and those who received partial treatment (P=.3)

Secondary Efficacy End Points

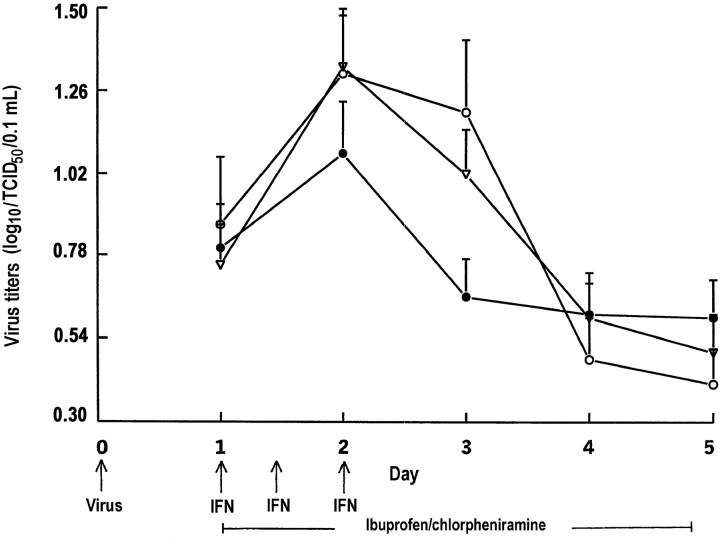

Virus titers Figure 2 shows the unadjusted geometric mean virus titers (GMTs) on days 1–5 of the 130 subjects infected with rhinovirus type 39. Subjects with wild virus infection before challenge were excluded from the analysis. After adjustment for the GMTs on day 1, the GMTs differed across the 3 study arms only on day 3. On day 3, the mean GMT was 1.64-fold greater (95% CI, 1.10–2.43; P=.015) for the group who received the placebo than for the group who received partial treatment and 1.55-fold greater (95% CI, 1.12–2.16; P=.01) for the group who received partial treatment than for the group of patients who received full treatment

Figure 2.

Geometric mean (+SE) virus titers (log10/TCID50/0.1 mL) of 130 subjects infected with rhinovirus type 39 (•, intranasal interferon [IFN], oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=51 subjects; ▿, intranasal placebo, oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=52 subjects; ○, intranasal and oral placebos; n=27 subjects)

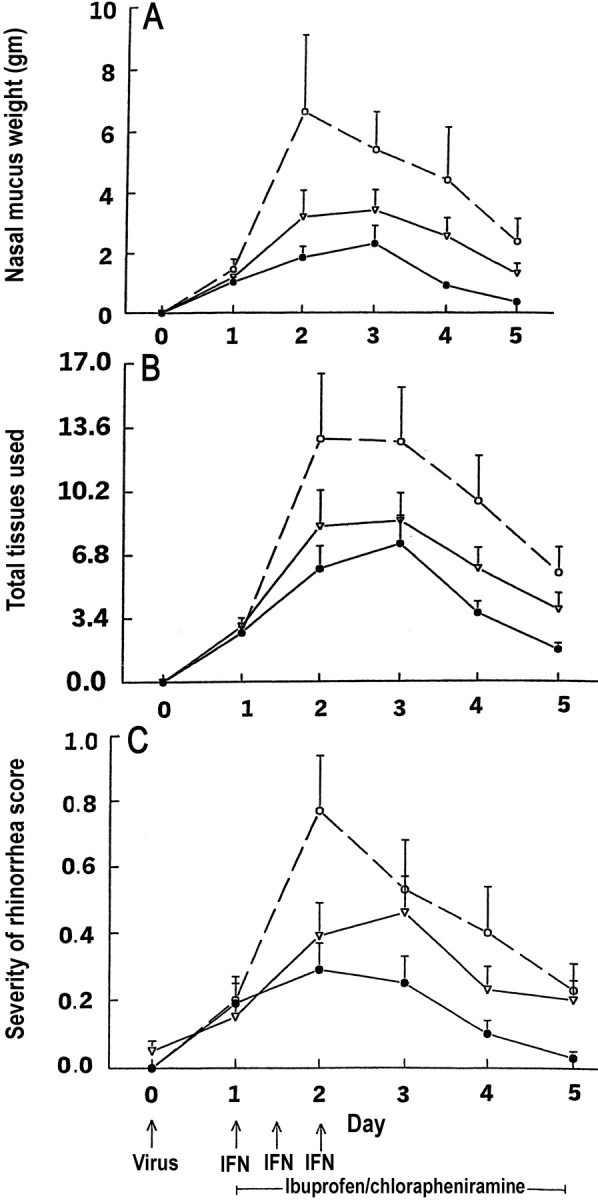

Nasal mucus weight Figure 3 shows the unadjusted mean weights of the nasal mucus collected on days 1–5. The baseline-adjusted means (±SE) for the total weight (in grams) of nasal mucus collected on days 2–5 were as follows: placebo group, 12.8±3.1; partial treatment group, 7.6±1.3; and full treatment group, 4.65±0.8. After adjusting for the subject’s nasal mucus weight on day 1, the estimated mean for the total weight of the nasal mucus that was collected per subject on days 2–5 was 2.74-fold greater (95% CI, 1.54–4.90; P<.001) for the placebo group than for the full-treatment group, 1.67-fold greater (95% CI, 0.94–2.97; P=.08) for the placebo group than for the partial treatment group, and 1.64-fold greater (95% CI, 1.03–2.63; P=.04) for the partial treatment group than for the full treatment group

Figure 3.

Mean (+SE) nasal mucus weights (A) nasal tissue use (B) and severity of rhinorrhea scores (C) in adults with rhinovirus colds (•, intranasal interferon [IFN], oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=59 subjects; ▿, intranasal placebo, oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=61 subjects; ○, intranasal and oral placebos; n=30 subjects)

Number of nasal tissues used Figure 3B shows the unadjusted mean number of nasal tissues used per subject on days 1–5. The baseline-adjusted means (±SE) for the total tissues used per subject on days 2–5, by group, were 33.9±6.6, placebo group; 18.8±2.6, partial treatment group; and 14.6±2.05, full treatment group. After adjusting for the subject’s tissue usage on day 1, the estimated mean for the total number of tissues used per subject was 2.39-fold greater (95% CI, 1.49–3.83; P<.001) for the placebo group than for the full treatment group and 1.80-fold greater (95% CI, 1.13–2.87; P=.01) for the placebo group than for the partial treatment group. Among subjects who received full or partial treatment, the total tissue usage was not significantly different (P>.15)

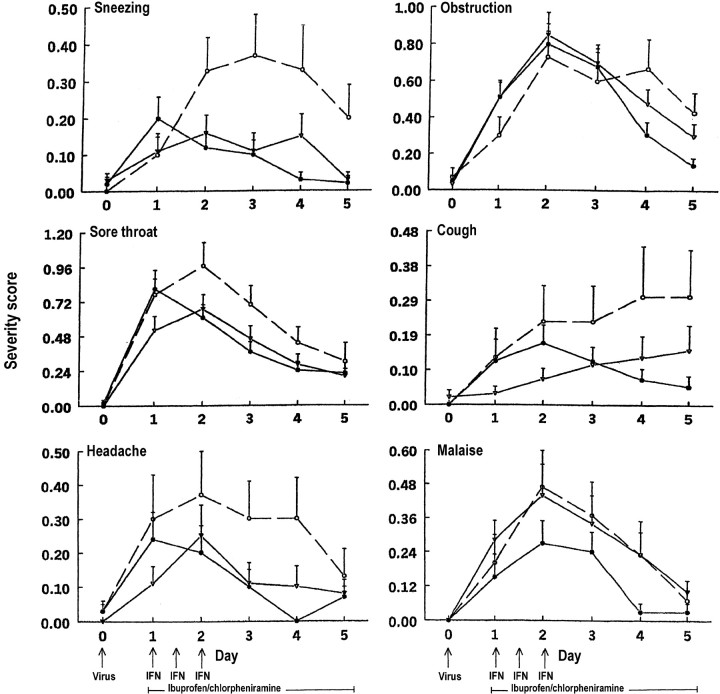

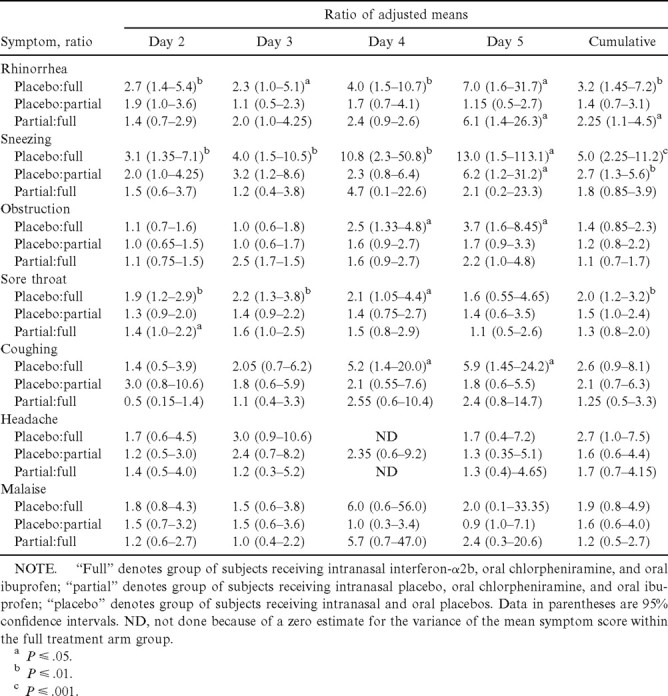

Specific symptom scoresLarge and sustained treatment effects on rhinorrhea symptom scores (table 3, figure 3) and sneezing symptom scores (table 3, figure 4) appeared between the full treatment and placebo groups after 24 h of treatment. A moderate treatment effect on nasal obstruction symptom scores appeared between the full treatment and placebo groups after 3 days of treatment (table 3, figure 4), and a moderate and sustained treatment effect on sore throat symptom scores appeared between the full treatment and placebo groups after 24 h of treatment (table 3, figure 4). A large treatment effect on coughing symptom scores appeared between the full treatment and placebo groups after 3 days of treatment, a time when cough scores were continuing to increase in the placebo group (table 3, figure 4). Mean headache symptom scores were lower in the full treatment than in the placebo group on all days of treatment, but the differences were not statistically significant (table 3, figure 4), nor were statistically significant differences in mean malaise symptom scores observed among the groups (table 3, figure 4)

Table 3.

Comparisons between baseline-adjusted mean daily symptom scores and cumulative symptom scores, days 2–5

Figure 4.

Mean (+SE) severity of sneezing, nasal obstruction, sore throat, cough, headache, and malaise scores in adults with rhinovirus colds (•, intranasal interferon [IFN], oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=59 subjects; ▿, intranasal placebo, oral chlorpheniramine, and oral ibuprofen; n=61 subjects; ○, intranasal and oral placebos; n=30 subjects)

Side Effects and Safety

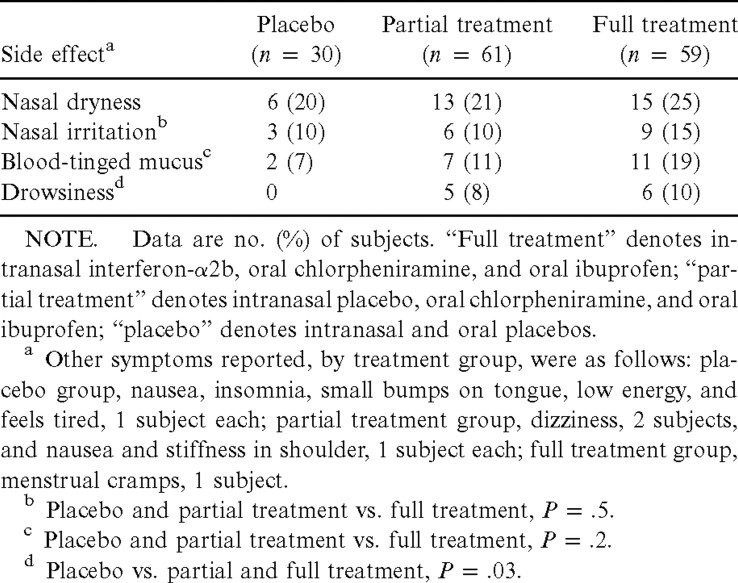

Nasal dryness occurred in 20% of the placebo, 21% of the partial treatment, and 25% of the full treatment groups (table 4). Nasal irritation occurred in 10% of the placebo and partial treatment groups and in 15% of the full treatment group. Blood-tinged nasal mucus occurred in 7% of the placebo group, 11% of the partial treatment group, and 19% of the full treatment group (placebo and partial treatment vs. full treatment, P=.2). Drowsiness occurred in 8% and 10% of the partial and full treatment groups, respectively, and in none of the placebo group (placebo vs. partial and full treatment, P=.03)

Table 4.

Side effects of interferon (IFN) and chlorpheniramine-ibuprofen treatment of rhinovirus colds

Following treatment, one volunteer in the placebo and one in the full treatment group had small blood crusts in the nasal passage. A small nasal polyp was noted in the posterior middle meatus in one volunteer in the full treatment group. Because of its location, the polyp may have been missed during the pretreatment examination

Discussion

Currently available cold treatments provide only partial relief in treating colds [2]. Decongestants relieve nasal obstruction (and, to some extent, rhinorrhea) but do not reduce sneezing, sore throat, cough, or general symptoms [2, 23]. First-generation antihistamines reduce sneezing, rhinorrhea, and possibly cough but not other cold symptoms [2, 10-13]. NSAIDs reduce general symptoms, sore throat, and cough [14–18]. The experimental approach with antivirals has been successful in preventing infection but has been less effective as a treatment after symptoms have appeared. Enviroxime, IFN, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule–1, which reduce virus concentrations in nasal fluid of infected subjects, have only a limited effect on symptom reduction [3–6]

The results of this study support the hypothesis that an antiviral–anti-inflammatory combination provides a more effective approach to treating colds than single-ingredient treatments. The combined treatment with IFN-α, chlorpheniramine, and ibuprofen tested in this study reduced individual and total symptoms scores and reduced nasal mucus production and virus concentration in nasal secretions. In subjects who were symptomatic when treatment was started, the full treatment resulted in a 33%–73% reduction in the daily mean total symptom severity score during the 4.5 days of treatment. The combination treatment was also well tolerated. Although nasal irritation occurs when intranasal IFN application is extended past several days [24], the abbreviated dosage schedule used in this study and in an earlier study [6] did not cause this problem. This dosage schedule was selected because of the prolonged antiviral state that IFN confers on nasal cells and the course of rhinovirus replication in the nose, which peaks at 48 h and then falls. Other antivirals would be candidates for use in combination therapy

In this study, treatment was initiated in the early stage of illness. A common practice in self-medication for colds is to begin treatment after symptoms are well established. However, the symptom burden of rhinovirus and nonrhinovirus colds is greatest during the first 3 days of illness [25, 26]. Attacking symptoms after the cold is well developed is not an ideal strategy. A better strategy is to initiate treatment when the illness is first beginning and thus to prevent the symptom burden from ever reaching its peak. Early recognition of the onset of a cold appears to be practicable. In a study of patients with natural colds, 81% reported that the interval between the initial recognized symptom and when the patients “knew they had a cold” was ⩽16 h [27]. This suggests that most persons can recognize early cold symptoms and thus initiate early treatment. An additional benefit of early treatment in this study was the reduction of the amount of nasal fluid produced and the need for nose blowing. The full treatment reduced expelled nasal fluid volume by 71% and nasal tissue use by 55%. This may result in less nasal fluid being propelled into the sinuses by nose blowing [28]

With the development of more effective cold treatments and with education, the public may adopt the practice of early cold treatment. More effective means of treating colds can lead to reduction of common cold morbidity and may help solve the continuing problem of the misuse of antibiotics for treating colds

Footnotes

The Human Investigation Committee, University of Virginia, reviewed the protocol. Subjects gave written consent for study participation

The authors and the University of Virginia have a financial interest in the technology of combined antiviral-antimediator cold treatment described

References

- 1.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Rueckert RR. Rhinovirus. In: Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, editors. Clinical virology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 1025–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MB, Feldman W. Over-the-counter cold medications: a critical review of clinical trials between 1950 and 1991. JAMA. 1993;269:2258–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.17.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillpotts RJ, Wallace J, Tyrrell DAJ, Tagart VB. Therapeutic activity of enviroxime against rhinovirus infection in volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:671–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden FG, Gwaltney JM., Jr Intranasal interferon-α2 treatment of experimental rhinoviral colds. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:174–80. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner RB, Wecker MT, Pohl G, et al. Efficacy of tremacamra, a soluble adhesion molecule 1, for experimental rhinovirus infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:1797–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.19.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwaltney JM., Jr Combined antiviral and antimediator treatment of rhinovirus colds. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:776–82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner RB, Felton A, Kosak K. Kelsey DK, Meschievitz CK. Prevention of experimental coronavirus colds with intranasal α-2b interferon. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:443–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperber SJ, Hayden FG. Comparative susceptibility of respiratory viruses to recombinant interferons-α2b and -β. J Interferon Res. 1989;9:285–93. doi: 10.1089/jir.1989.9.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins PG, Barrow GL, Tyrrell DAJ, Isaacs D, Gauci CL. The efficacy of intranasal interferonα-2a in respiratory syncytial virus infection in volunteers. Antiviral Res. 1990;14:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(90)90061-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle WJ, McBride TP, Skoner DP, Maddren BR, Gwaltney JM., Jr A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effect of chlorpheniramine on the response of the nasal airway, middle ear and eustachian tube to provocative rhinovirus challenge. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:229–38. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198803000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Park J, Paul RA, Edelman DA, O’Connor RR. Connor RR. Randomized controlled trial of clemastine fumarate for treatment of experimental rhinovirus colds. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:656–62. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner RB, Sperber SJ, Sorrentino JV, et al. Effectiveness of clemastine fumarate for treatment of rhinorrhea and sneezing associated with the common cold. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:824–30. doi: 10.1086/515546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Druce HM. Efficacy of brompheniramine maleate treatment for rhinovirus colds. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1188–94. doi: 10.1086/516105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insel PA. Analgesic-antipyretin and antiinflammatory agents and drugs employed in the treatment of gout. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 617–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas M, Del Mar C, Glasziou P. How effective are treatments other than antibiotics for acute sore throat. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:817–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperber SJ, Hendley JO, Hayden FG, Riker DK, Sorrentino JV. Effects of naproxen on experimental rhinovirus colds: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:37–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Tettamanti F, Malamani GD, Tinelli C. Effects of nifedipine and indomethacin on cough induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a double-blind, randomized, cross-over study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19:670–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozhat JRM, Choudry B, Fuller RW. The effect of sulindac on the abnormal cough reflex associated with dry cough. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couch RB. Laboratory diagnosis of viral Infection. 2d ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. Rhinovirus; pp. 709–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson GG, Dowling HF, Spiesman IG, Boand AV. Transmission of the common cold to volunteers under controlled conditions. I. The common cold as a clinical entity. Arch Intern Med. 1958;101:267–78. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1958.00260140099015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang K-Y. Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron CA, Pravin KT. Econometric Society Monographs, no 30. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Regression analysis of count data; pp. 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sperber SJ, Sorrentino JV, Riker DK, Hayden FG. Evaluation of an alpha agonist alone and in combination with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent in the treatment of experimental rhinovirus colds. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1989;65:145–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farr BM, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Adams KF, Hayden FG. Intranasal interferon-α2 for prevention of natural rhinovirus colds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:31–4. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Hendley JO, Simon G, Jordan WS., Jr Rhinovirus infections in an industrial population. II. Characteristics of illness and antibody response. JAMA. 1967;202:494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao SS, Hendley JO, Hayden FG, Gwaltney JM., Jr Symptom expression in natural and experimental rhinovirus colds. Am J Rhinol. 1995;9:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arruda E, Pitkaranta A, Witek TJ, Doyle CA, Hayden FG. Frequency and natural history of rhinovirus infections in adults during autumn. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2864–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2864-2868.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Hendley JO, Phillips CD, Bass CR, Mygind N. Nose blowing propels nasal fluid into the paranasal sinuses. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:387–91. doi: 10.1086/313661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]