Abstract

The association between poverty and the activity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis in early childhood is well established. Both ecological and transactional theories suggest that one way in which poverty may influence children’s HPA-axis activity is through its effects on parents’ behaviors, and over the past three decades a substantial literature has accumulated indicating that variations in these behaviors are associated with individual differences in young children’s HPA-axis activity. More recent research suggests that non-parental caregiving behaviors are associated with HPA-axis activity in early childhood as well. Here we systematically review the literature on the association between both parental and non-parental caregiving behaviors in the context of poverty and the activity of the HPA-axis in early childhood. We conclude by noting commonalities across these two literatures and their implications for future research.

Keywords: poverty, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis, parenting, caregiving behaviors, early education, early childhood

The effects of poverty on child development are a pressing societal concern. Recent estimates suggest that more than 15 million children in the United States are living in poverty (Koball & Jiang, 2018). Decades of research suggest strong linkages between poverty and poor developmental outcomes (see, for example, Evans, Li, & Whipple, 2013; McEwen & McEwen, 2017). These findings have been supported by a growing experimental literature examining income-supplement or anti-poverty programs, all of which suggest that poverty has a negative impact on children’s development (e.g., Costello, Compton, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Huston et al., 2001; McLoyd, Kaplan, Purtell, & Huston, 2011). These effects may be particularly pronounced for young children (for reviews, see Engle & Black, 2008; Carnegie Task Force, 1994): experiencing poverty in early childhood, as opposed to later childhood, strongly predicts the subsequent development of psychiatric problems (Rutter, 1975), academic difficulties (Lipman, Offord, & Boyle, 1997), and the failure to complete high school (Brooks-Gunn, Guo, & Furstenberg, 1993; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998). Moreover, poverty in early childhood has detrimental effects on measures of attainment 20 to 30 years later, including reduced earnings and work hours (Duncan, Ziol-Guest, & Kalil, 2010).

The strength and persistence of these associations may be explained, in part, by findings from both human and animal research suggesting that there are discrete periods of postnatal development when key neurophysiological processes are consolidated and are especially sensitive to environmental input (Fox, Levitt, & Nelson, 2010; Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2015). The effects of early experience on neurophysiological development extend to the organization and consolidation of the stress response system, and one of the main components of that system is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Chrousos & Gold, 1992; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). Through the release of corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF), the hypothalamus regulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the blood stream by the pituitary gland (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006; Stratakis & Chrousos, 1995). ACTH binds to receptors on the adrenal cortex, promoting the secretion of the glucocorticoid (steroid hormone) cortisol (Gunnar, 1992). Under homeostatic conditions – in which threats or other aversive stressors are absent – cortisol production is relatively low, and much of the cortisol produced is bound and thus rendered inert by mineralcorticoid receptors (MRs; de Kloet, 1991). However, when a threat or stressor is encountered, the production of CRF, ACTH, and cortisol increases. As cortisol levels rise it begins to bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs; de Kloet, Rots, & Cools, 1996), which prompts a number of metabolism-enhancing effects (including freeing stores of glucose) that facilitate the behavioral response to challenge (Sapolsky, 1996).

Thus, the term “HPA-axis activity” encompasses at least two distinct types of activity: activity under conditions of homeostasis and activity under conditions of stress or challenge. In older children and adults, the activity of the HPA axis under conditions of homeostasis follows a predictable diurnal rhythm, with levels of cortisol peaking shortly after waking and then declining steadily over the course of the day (Edwards, Evans, Hucklebridge, & Clow, 2001). However, this pattern emerges over the course of early childhood. Newborns and young infants exhibit two peak levels of cortisol approximately 12 hours apart (Klug, Dressendorfer, Strasburger, Kuhl, Reiter, Reich, et al., 2000), and while the circadian rhythm begins to emerge at 3 months (de Weerth et al., 2003; Matagos, Moustogiannis, & Vagenakis, 1998), it is not firmly established until children abandon their naps (Watamura, Sebanc, & Gunnar, 2002). In early childhood HPA-axis activity under conditions of challenge also differs from that seen in older children and adults. Although young infants display elevations in cortisol in response to a variety of stressors (Gunnar, Brodersen, Krueger, & Rigatsu, 1996; Ramsay & Lewis, 1994), between six months and two to three years of age it becomes increasingly difficult to provoke this response (Gunnar et al., 1996; Gunnar et al., 1989; Gunnar & Nelson, 1994; Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996). Researchers have argued that this dampened stress response may be the human analog of the selective hyporesponsive period of HPA-axis activity observed in young rodents (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Sapolsky et al., 1996).

These age-related changes in HPA-axis activity over the course of early childhood may require defining adaptive and maladaptive HPA-axis activity by referencing patterns of activity that would be considered typical at a given age. For example, failing to exhibit an increase in HPA-axis activity in response to an aversive challenge at three months of age may be maladaptive, given that at three months most children will demonstrate this response (Gunnar et al., 1996; Ramsay & Lewis, 1994). However, at 18 months the same pattern of activity would be considered adaptive, given that a dampened HPA-axis response to challenge is typical at this age (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Sapolsky et al., 1996). Only once patterns of HPA-axis activity have become consolidated is it possible to characterize HPA-axis activity along a single continuum, in which activity at the poles of the continuum may be considered maladaptive and activity towards the center may be considered adaptive.

At one end of this continuum lies hypercortisolism, or frequent and prolonged activation of the HPA axis, which may be manifest as high levels of cortisol under conditions of homeostasis and large increases in cortisol in response to challenge (Fries, Hesse, Hellhammer, &Hellhammer, 2005; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006). Higher levels of cortisol under conditions of homeostasis may be attributable, in part, to “flattened” patterns of diurnal HPA-axis activity, in which the typical decline in cortisol levels over the course of the day is attenuated. These flattened patterns of cortisol are often accompanied by lower levels of waking cortisol, with the net result being elevated overall cortisol production throughout the day (Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007). At the other end of the continuum is hypocortisolism, which is indicated by very low levels of cortisol under homeostatic conditions and a “blunted” response to challenge (Fries, Hesse, Hellhammer, & Hellhammer, 2005; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006). These altered patterns of HPA-axis activity may constitute a recalibration or allostasis in response to environmental conditions (McEwen & Seeman, 1999). Specifically, exposure to acute stress that is extreme in intensity or duration may result in hypercortisolism, whereas hypocortisolism may be indicative of habituation of the HPA axis to chronic stress (Fries, Hesse, Hellhammer, & Hellhammer, 2005; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006). Hypercortisolism may, in fact, lead to hypocortisolism over the course of development, as the hippocampal feedback circuits that modulate HPA-axis activity become dysregulated by exposure to elevated levels of cortisol (Gunnar & Vasquez, 2001; Susman, 2006). Although these patterns of altered HPA-axis activity may be adaptive in the short term, over time they may impose a heavy allostatic load on children’s development (McEwen, 1998; McEwen, 2000). For example, hypercortisolism may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance, impair immune functioning, and promote atrophy in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Bremner & Vermetten, 2001; McEwen, 2006), whereas hypocortisolism has been linked with autoimmune and chronic pain disorders, disrupted self-regulatory abilities, and inhibited growth (e.g., Blair, Granger, & Razza, 2005; Gunnar & Vazquez, 2001; Heim, Ehlert, & Hellhammer, 2000).

The malleability of HPA-axis function may explain how the experience of poverty gets “under the skin” of young children (Lupien et al., 2001). The environment of poverty is filled with stressors for children and their caregivers. Families in poverty are more likely to live in homes with holes in the floor and ceiling, inadequate heat and plumbing, rodent or other pest infestations, greater crowding, noise pollution, and toxins (for reviews, see Children’s Defense Fund, 1995; Evans, 2004), and in concentrated areas of poverty there may be increased rates of criminal activity, violence, and homicides (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Boyce and Ellis (2005) argue that early exposure to environmental adversity promotes hyperactivity of the physiological response to stress, and, in accordance with this account, studies employing variable-centered (Lupien et al., 2001; Zalewski et al., 2012a) and person-centered (Holochwost et al., 2017; Laurent et al., 2014) approaches have linked poverty to dysregulated HPA-axis activity in young children. Dysregulation of the HPA-axis activity in early childhood has, in turn, been found to predict subsequent outcomes across a number of domains, including social and cognitive function (e.g., Blair et al., 2005).

In this paper we explore what imbues poverty with the power to influence development, and, in particular, the HPA axis. While there is no single answer to such a complex question, an integration of ecological (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and transactional (McLoyd, 1998) theories suggests that poverty – an aspect of the child’s distal environment – affects development through its influence on more proximal systems. For the young child, relationships with parental caregivers are a particularly salient aspect of the proximal environment, and thus the tendency for poverty to erode parental caregivers’ capacity to engage in positive behaviors while increasing the likelihood that they will engage in negative behaviors (Holochwost et al., 2016; Popp, Spinrad, & Smith, 2008), may, in part, explain how poverty influences HPA-axis activity (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2015). And yet this account is incomplete, given that the social conditioning of HPA-axis activity occurs through interactions with caregivers other than children’s parents (Flinn, 1999; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Hostinar, Sullivan, & Gunnar, 2014) and that many young children spend a considerable amount of their time with non-parental caregivers in early care and education settings (Capizzano & Main, 2005; Corcoran & Steinley, 2017). Therefore, and in accordance with the contextual systems model (CSM; Pianta & Walsh, 1996), in order to understand how poverty may influence HPA-axis activity through its effects on parental caregiving behaviors, it is necessary to understand the influence that poverty may exert through non-parental caregiving behaviors as well.

Here we present a systematic review of the literature on the associations between multiple dimensions of parental and non-parental caregiving behaviors and different aspects of young children’s HPA-axis activity. By reviewing studies that examined parental and non-parental caregiving behaviors, it was possible to identify points of convergence and divergence in findings across the parenting and early care and education literatures. By necessity, our review focuses on the direct associations between caregiving behaviors and HPA-axis activity, given that few studies have assessed the question of mediation. Although the results of our review clearly support the plausibility of a model in which parental and non-parental caregiving behaviors mediate the association between poverty and HPA-axis activity, this does not render an alternative model in which these behaviors moderate this association implausible. In the discussion we outline specific directions for future research designed to test the mediation model that is the focus of this paper, as well as considerations that may complicate this model.

Parental Caregiving Behaviors in the Context of Poverty

As noted above, families in poverty often face dangerous living situations in their homes and neighborhoods (Children’s Defense Fund, 1995; Evans, 2004), but impoverished parents face a host of additional stressors beyond the physical environment. For example, the employment opportunities available to low-income parents are often unstable and high in stress, involving non-standard shifts, long work hours, and little self-direction (Hsueh & Yoshikawa, 2007; Parcel & Menaghan, 1997). Impoverished families may also experience greater social isolation than those with more financial resources (Belle, 1983), and their family and friend networks may add additional strain due to their own financial difficulties (Brodsky, 1999). The pressure of being forced to make cutbacks to make ends meet or the inability to provide for family necessities can add further tension to parents’ lives (e.g., Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd, & Brody, 2002).

In extreme cases, poverty may increase the likelihood of child maltreatment (Drake & Zuravin, 1998). A disproportionate number of families in poverty are reported for abuse (Trickett, Aber, Carlson, & Cicchetti, 1991), and the sensations of powerlessness that living in poverty can create may further heighten the potential for maltreatment (Bugental & Happaney, 2004). Maltreatment in early childhood has, in turn, been linked to altered patterns of HPA-axis activity under conditions of both homeostasis (Bernard, Butzin-Dozier, Rittenhouse, & Dozier, 2010; Bruce, Fisher, Pears, Levine, 2009) and challenge (Bugental, Martorell, Barraza, 2003; Hart, Gunnar, & Cicchetti, 1995).

However, for the vast majority of families in poverty, parenting behaviors do not encompass these extremes. Nevertheless, the experience of poverty may reduce parents’ ability to be sensitive and supportive while increasing the likelihood that they will engage in sub-optimal parenting behaviors (Bradley & Corwyn, 2001; McLoyd, 1990). For example, during interactions with their infants, impoverished mothers are more likely to be rated as insensitive than more affluent mothers (Pianta & Egeland, 1990; Shaw & Vondra, 1995) and to exhibit lower levels of emotional responsiveness (Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994). Parents in poverty are less likely to consider their children’s perspectives and empathize with their interests (Gerris, Deković,& Janssens, 1997), which may lead to higher levels of parent-child conflict over time (Hastings & Grusec, 1997).

Non-Parental Caregiving Behaviors in the Context of Poverty

Although parental caregiving behaviors are the sine qua non among influences on children’s development, many young children spend a substantial proportion of their waking hours in the care of people other than their parents. Recent data from the Early Childhood Program Participation (ECPP) Survey indicated that nationally 60% of children age 5 years or younger were in at least one form of non-parental care (Corcoran & Steinley, 2017); analyses of earlier data from the National Survey of America’s Families (NSAF) found that 42% of children under 5 spend at least 35 hours a week in care (Capizzano & Main, 2005). Despite the presence of barriers to access of affordable care (see below), many children in poverty do spend time in care: according to the ECCP Survey, 46% of these children are in non-parental care (Corcoran & Steinley, 2017), while NSAF data indicated that for children in low-income, single-parent households this figure was 79% (Adams et al., 2007). Indeed, welfare reform (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996) required single mothers of infants to work, effectively mandating that many low-income children be in non-parental care (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000).

While the non-parental caregiving arrangements for children in poverty vary widely (Zaslow et al., 2006), there is evidence that, on average, the quality of care is lower for poor children than it is for their more affluent peers (Adams et al., 2007; Howes & Olenick, 1986; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997; Phillips, Voran, Kisker, Howes, & Whitebook, 1994). Despite the importance of consistent caregiving arrangements for children’s development (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015; Rhodes & Huston, 2012; Tout et al., 2005), rates of turnover among early educators are among the highest of any profession (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000; Whitebrook et al., 2014), and these rates may be higher among caregivers of children in poverty, given the low wages paid to many of these caregivers (Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences, 2015; Whitebrook et al., 2014). Over a third of children in poverty (37%) are in multiple caregiving arrangements (Zaslow et al., 2006), a figure that excludes the common practice of cobbling together care on a day-to-day basis (Adams et al., 2007).

Even when care is stable, children in poverty are more likely to attend home-based care (NSECE Project Team, 2016), which may include relative care (Corcoran & Steinley, 2017). These types of care arrangements are generally less expensive and offer more flexibility than center-based care for parents who work long, irregular, or overnight hours (Hofferth, 1995; Porter, Paulsell, Nichols, Begnoche, & Del Grosso, 2010). However, they may also be of lower quality than center-based alternatives (Brown-Lyons, Robertson, & Layzer, 2001; Galinsky, Howes, Kontos, & Shinn, 1994; Tout & Zaslow, 2006), given the lower levels of resources and supports offered to providers of home-based care (Tonyan, Paulsell, & Shivers, 2017) and the fact that some forms of home-based care (e.g., family, friend, and neighbor care) are exempt from licensing requirements (Zaslow, Tout, & Martinez-Beck, 2010). When center-based care is available for children in poverty, it is likely to be of lower quality than center-based options for more affluent children (Marshall et al., 2001). For example, whereas ratings of Head Start classrooms have consistently reported quality scores at the threshold between “low” or “minimal” and “good” quality using a combination of measures (e.g., the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS; Harms & Clifford, 1980) and the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta, La Para, & Hamre, 2008); Aikens, Bush, Gleason, Malone, & Tarullo, 2016), average levels of quality are lower for classrooms that serve a majority of low-income children (Pianta et al., 2005).

There are a variety reasons that children in poverty are apt to receive lower-quality care, many of them market-driven (Adams et al., 2007). The structural features of high-quality care, such as specialized training for caregivers and low child-to-caregiver ratios, are expensive to provide (Marshall et al., 2001), and when the cost of this care is not subsidized it may be beyond the means of many low-income families (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2000). But these structural aspects of quality are a prerequisite, rather than a guarantor, of high-quality care. As noted by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2000):

Quality of care ultimately boils down to the quality of the relationship between the child care provider or teacher and the child. A beautiful space and an elaborate curriculum – like a beautiful home – can be impressive, but without skilled and stable child care providers, they will not promote positive development…Critical to sustaining high-quality child care for young children are the providers’ characteristics, notably their education, specialized training, and attitudes about their work and the children in their care, and the features of child care that enable them to excel in their work and remain in their jobs. (pp. 314–315, 318).

This account makes clear why non-parental caregivers of children in poverty may struggle to establish and maintain positive interactions with the children in their care. Like many parents of children in poverty, these caregivers are engaged in a stressful, demanding job (Friedman-Krauss, Raver, Neuspiel, & Kinsel, 2014), often with limited professional support (Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences, 2015), and, like many impoverished parents, caregivers of poor children are more likely to face social isolation (Porter et al., 2010), elevated levels of financial stress (Whitebrook et al., 2014) and depression (Whitaker et al., 2013; Whitebrook & Sakai, 2004). Indeed, many caregivers of children in poverty are themselves poor. On average, childcare workers earned $20,660 per year in 2013, placing them just above the poverty level for the family of three (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). Caregivers in home-based programs earned slightly less ($19,510 per year; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). It is perhaps not surprising that between 35 and 46% of caregivers reported using one or more forms of public assistance (Whitebrook et al., 2014). In short, many of the aspects of sociodemographic risk that have been found to erode parents’ ability to interact positively with their children – poverty, single-parenting status, and low levels of education – are present in large proportions of the caregiving workforce, of whom 16% fall below the poverty line, 17% are single parents, and 50% hold no more than a high school diploma (Whitebrook et al., 2014). Indeed, as Whitebrook and colleagues (2014) noted, many caregivers of children in poverty are also parents of children in poverty.

The Current Study

In summary, the activity of the HPA-axis is open to environmental input in early childhood, including input from environments of poverty and adversity (Holochwost et al., 2017; Laurent et al., 2014; Lupien et al., 2001; Zalewski et al., 2012a). Accordingly, and consistent with ecological systems (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and transactional theories (McLoyd, 1998), caregiving behaviors may transmit the effects of poverty to young children’s HPA-axis activity. Moreover, according to the contextual systems model (Pianta & Walsh, 1996) it is not possible to fully understand the association between one form of caregiving behavior, whether parental or non-parental, and HPA-axis activity without understanding the parallel association between the other form of caregiving behavior and HPA-axis activity. Thus, the fact that associations between various dimensions of parental caregiving behaviors and different aspects of HPA-axis activity are often reported without reference to parallel associations between non-parental caregiving behaviors and HPA-axis activity has impeded a fuller understanding of an essential mechanism by which poverty may influence the activity of the HPA axis in young children. So too has the tendency to report associations between non-parental caregiving behaviors and HPA-axis activity without acknowledging findings from the parenting literature. Therefore, in the remainder of this paper we present the results of a systematic review of the literature on the association between caregiving behaviors, first reviewing studies of parental caregiving behaviors in the context of poverty and then studies of non-parental caregiving behaviors in the same context. To the extent possible, the results of these studies are presented in a similar fashion to facilitate the identification of points of convergence and divergence between these two literatures.

Method

Search Strategy

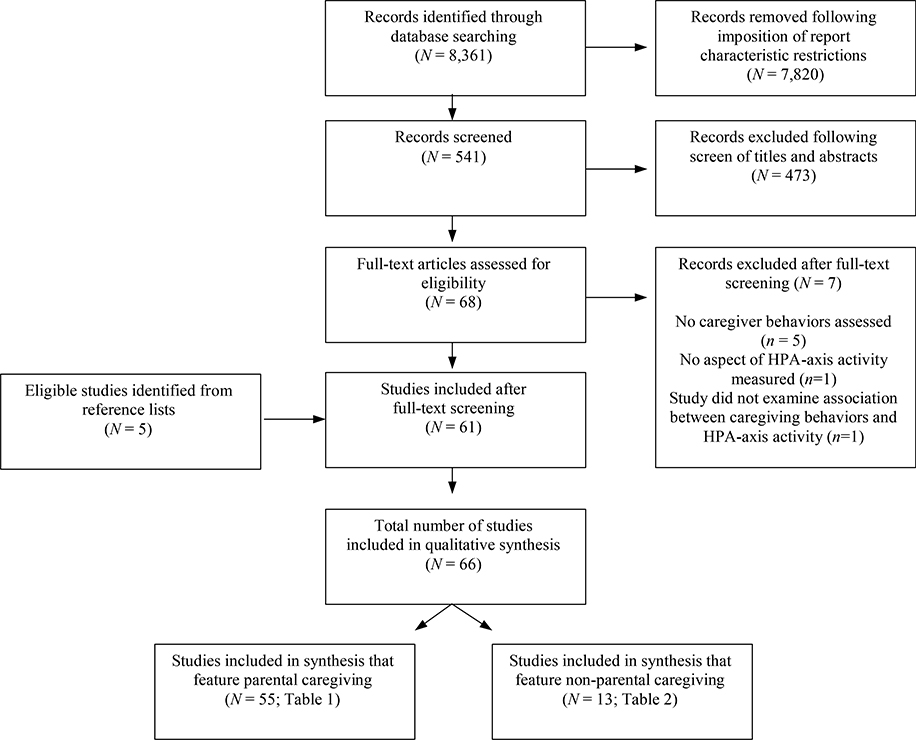

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to develop a protocol for reviewing the literature (Shamseer et al., 2015). To be included in the review, studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) participants were young children (birth to age 8 years) who were healthy and developing normally and 2) their caregivers, whether parental or non-parental; 3) some dimension of parental or non-parental caregiving behaviors were assessed; 4) some aspect of HPA-axis activity was measured, and 5) the study was designed to examine the association between some dimension(s) of caregiving behavior and some aspect(s) of HPA-axis activity. In addition to these study inclusion criteria, a series of report characteristics were also applied as inclusion criteria. Therefore, to be included in the review, a study also had to be: 1) empirical (which excluded letters, commentary, and case studies); 2) conducted with human children who were neonates, infants, or preschoolers; and 3) were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. No date limitations were placed on the search results. Previous research has demonstrated that excluding papers published in languages other than English does not necessarily bias the results of reviews (Morrison et al., 2012), and including only papers that underwent peer review is one means of ensuring the quality of studies (cf., Lawson et al., 2018) without resorting to potentially-problematic quality assessment tools (Siddaway et al., 2019)

Two databases (PsycInfo and Medline) were searched concurrently using the following combination of keywords that were based on the study inclusion criteria: [“parent*” OR “childcare” OR “caregiv*” OR “teacher*” OR “early education” OR “preschool”] AND [“cortisol” OR “hypothalamic*” OR “HPA*”]. The results of the search were then narrowed by applying the reporting inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the studies that were ultimately included in the review following full-text screening (see below) were also consulted to identify any additional records not yielded through the database search. The final search was conducted in June, 2019.

Study Selection

The records yielded by the database search, including titles and abstracts, were exported into a spreadsheet. The title and abstract of each study was screened by the first author using the study inclusion criteria. When the decision was made to exclude a study, the reason for doing so was selected from one of the following options: 1) participants were not young children (defined as birth to age 8 years) and 2) their caregivers; 3) no caregiving behaviors were assessed; 4) no aspect of HPA-axis activity was measured, or 5) the study did not examine the association between some dimension(s) of caregiving behavior and some aspect(s) of HPA-axis activity.

These same inclusion criteria were then applied to the full texts of the papers that passed the review of titles and abstracts. The full texts of all studies were reviewed by the first author. Approximately half (51%) of these full texts were selected at random for independent review by either the fourth or final author, with both of these authors assigned approximately half of the full texts selected for independent review. When the decision was made to exclude a study, the reviewing author made a note of the reason using one of the options listed above. The first and second readers agreed in each case about which papers to include in the review, and, in those cases when the decision was made to exclude a study, both readers agreed about the reason for doing so. Finally, the first author applied the inclusion to the reference lists of the studies that passed the full text review.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Once the studies that were to be included in the review had been identified, the fourth author extracted relevant data using a form that included the following fields: 1) type(s) of caregiving behaviors (parental/non-parental); 2) sample size; 3) the composition of the sample in terms of age and socioeconomic composition; 4) the dimension(s) of caregiving behaviors assessed and how those dimensions were measured; 5) the aspect(s) of HPA-axis activity measured and the method and timing of measurement; and 6) the major findings of the study. This form was developed and piloted by the first and final authors, who then together trained the fourth author in its use. As data were extracted by the fourth author, the first author reviewed all entries in the form and asked clarifying questions as appropriate to ensure reliability in the data extraction process. During the extraction process two points became clear: first, it was necessary to add a notes section to the extraction form about important design issues, such as whether a study was a randomized-control trial of an intervention for caregivers. Second, a number of studies used the same or partially-overlapping samples, and therefore this was noted on the form as well. Given that these studies examined different associations between dimensions of caregiver behaviors and aspects of HPA-axis activity and that the results of the review were not subject to quantitative analysis (see below), studies that used the same were retained.

The data from the extraction form were reformatted as a pair of tables that reflected the goal of the study: to systematically review the literature on the associations between dimensions of parental and non-parental caregiving behaviors and different aspects of HPA-axis activity in early childhood. As such, Table 1 included the data listed above that was drawn from studies of parental caregiving behaviors, while Table 2 presented the analogous data drawn from studies of non-parental caregiving behaviors. Where multiple studies were based on the same sample this is noted in the table and text. Both tables reported the same extracted data, and these data were reported in a way that facilitated the comparison of findings across studies of parental and non-parental caregiving. For example, diurnal HPA-axis activity was defined as activity observed under homeostatic conditions at multiple timepoints over the course of the day, and the timing of data collection was reported for all studies that examined the association between caregiving behaviors, whether parental or non-parental, and diurnal HPA-axis activity, thus defined.

Table 1.

Studies of parental caregiving behaviors and HPA axis activity

| Study | Participants | Assessment of Parenting Behaviors | Measurement of HPA Axis Activity | Summary of Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age & Socioeconomic Composition | Construct(s) | Measurement | Conditions | Method & Timing | Major Findings | Notes | |

| Albers et al., 2008 | 64 | Infants & Toddlers (M=12.2 mos.) (SD=2.5 mos.) Income not reported. Mean maternal education was 6.22 on a scale ranging from 1 (elementary school) to 7 (university degree). |

Maternal sensitivity and cooperation | Observation during bath | Baseline, Reactivity (bath) | Salivary cortisol was obtained before bath and then 25 and 40 m after bathing. | Higher levels of maternal sensitivity and cooperation during bath time were associated with faster recovery of cortisol levels to baseline levels. | |

| Albers et al., 20161 | 64 | Infants (M=14.6 wks.) (SD=2.8 wks.) Income not reported. 34 mothers (53.1%) had a professional degree and 29 (45.3%) had at least one university degree. |

Maternal sensitivity and cooperation | Observation during bath | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was obtained in the morning (10–10:30 a.m.) and afternoon (4–4:30 p.m.) while children were in care. | Higher levels of maternal sensitivity and cooperation during bath time exhibited higher morning cortisol while in care. Similar results were observed in the afternoon only among infants rated high in negative emotionality. |

|

| Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008 | 130 | Toddlers (M=28.3 mos.) (SD=10.3 mos.) Income not reported. Mean maternal education was 3.72 on a scale ranging from 1 (elementary school) to 5 (university degree). |

Maternal sensitivity and discipline | n/a | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected at home by parents on a typical day within a week before the post test upon children’s waking, before lunch, and in the afternoon. | Receipt of an intervention (VIPP-SD2) designed to improve maternal behavior was associated with reductions in diurnal cortisol levels among children with the DRD4 7-repeat allele. | Intervention study (featuring random assignment to a program designed to improve parental caregiving behaviors). |

| Bernard & Dozier, 2010 | 32 | Toddlers (M=15.2 mos.) (SD=2.3 mos.) Annual household income ranged from $10,000 to $100,000, with 53% of households earning more than $100,000. |

Attachment security and organization | Observation during free play and the SSP3 | Baseline Reactivity (SSP) | Salivary cortisol at at the child’s home, upon the child’s arrival at the lab, and 40, 65, and 80 m after arrival. | Infants rated as disorganized exhibited elevations in cortisol in response to free play and larger elevations in response to the SSP; infants rated as organized infants did not exhibit elevations in response to either task. | |

| Berry et al., 20174 | 1292 | Infants & Toddlers (7–24 mos.) The majority (67%) of families had an annual household income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation during a semi-structured interaction session5 | Baseline | Salivary cortisol was collected at home at 7, 15, and 24 mos. of child age. | Children whose mothers displayed lower levels of sensitivity across ages exhibited higher levels of overall, cross-age cortisol. Among mother-child dyads characterized by low overall levels of maternal sensitivity, increases in maternal sensitivity over time were associated with decreases in cortisol levels. Among mother-child dyads characterized by high overall sensitivity, increases in sensitivity were associated with increases in cortisol levels. |

Analyzed between-child differences in levels of cortisol across age and longitudinal, within-child associations between sensitivity and cortisol. |

| Blair et al, 2015 | 1292 | Toddlers (M=24 mos.) The majority (67%) of families had an annual household income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. |

Parental sensitivity (over 90% mothers) |

Observation during a semi-structured interaction session3 | Baseline Reactivity (a fear-inducing mask presentation following a toy removal procedure6) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to the stress task, ∼20 m after the child reached peak emotional arousal, and ∼40 m after peak arousal. | Children evidencing emotional liability to the fear-inducing mask and whose parents displayed higher levels of sensitivity exhibited elevated baseline cortisol and greater reactivity. The association between liability and cortisol was not observed among children whose parents displayed lower levels of sensitivity. |

The focal predictor of cortisol was children’s emotional liability; parental sensitivity was included as a moderator. |

| Blair et al., 2008 | 1292 | Infants (M=7.6 mos.) Toddlers (M=15.7 mos.) The majority (67%) of families had an annual household income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. |

Maternal positive engagement and intrusiveness | Observation during free play | Baseline, Reactivity (Infancy7) (Toddlerhood8) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to free play, 20 m after peak emotional arousal, and 40 m after peak arousal. | Maternal engagement in infancy was associated with: 1) higher levels of reactivity in infancy, and 2) lower overall levels of cortisol in toddlerhood. | Peak arousal was determined by the data collectors using clear guidelines established in the experimental protocol. Peak arousal for the majority of infants occurred at the conclusion of the emotional challenge tasks at both time points. |

| Blair, Granger, et al., 2011 | 1292 | Infants (∼7 mos.) Toddlers (∼15 & 24 mos.) Preschoolers (∼36 mos.) The majority (67%) of families had an annual household income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. |

Maternal positive parenting9 and negative10 parenting | Observation during free play (7 and 15 mos.) | Baseline | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to free play. | Baseline cortisol levels were negatively related to positive parenting across age, but unrelated to negative parenting. | In combination with positive and negative parenting and household risk, cortisol mediated effects of income-to-need, maternal education, and African American ethnicity on child cognitive ability. |

| Blair, Raver, et al., 2011 | 1135 | Infants (∼7 mos.) Toddlers (∼15 & 24 mos.) Preschoolers (∼36 & 48 mos.) The majority (67%) of families had an annual household income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. |

Maternal positive parenting and negative parenting | Observation during free play (7 and 15 mos.) | Baseline | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to free play. | Lower levels of maternal sensitivity were associated with higher levels of baseline cortisol from 7 to 48 mos. | |

| Bugental et al., 2003 | 44 | Toddlers (M=17.6 mos.) (SD=4.7 mos.) Income not reported. Participating mothers were classified as high risk on the basis of low education, low social support, high stress, and a history of abuse as children. |

Maternal emotional withdrawal11 | Self-repot (CTS)12 | Baseline Reactivity (SSP13) | Salivary cortisol was collected after an unstructured interaction between mothers and infants and 20 m after the SSP. | Frequent maternal emotional withdrawal was associated with elevated baseline cortisol levels. | |

| Bugental et al., 2010 | 64 | Infants (M=9 wks.) (SD=5.5 wks.) Income not reported. Participating mothers were classified as high risk on the basis of low education, residential instability, and limited English language proficiency. |

Parenting knowledge | Self-report (CTS) | Basal | Salivary cortisol was collected in the morning (∼10 a.m.) once a year over the course of three years. | At the 1- and 3-year assessments, infants of parents assigned to the treatment condition exhibited lower levels of baseline cortisol. Infants of parents assigned to the treatment condition also exhibited declining cortisol over time. |

Intervention study (featuring random assignment to a year-long program designed to enhance caregivers’ knowledge about parenting). |

| Cicchetti et al., 2011 | 143 | Infants & Toddlers (M=13.3 mos.) (SD=0.8 mos.) Mean annual household income was $16,646. 96% of participating families were receiving public assistance. |

Maternal sensitivity | History of maltreatment served as a proxy measure | Basal | Salivary cortisol was collected in the morning four times over the course of two years. | Maltreated infants whose families received standard services exhibited declining cortisol levels over time. Maltreated infants whose families participated in the program exhibited cortisol levels that were no different from those exhibited by children who were not maltreated |

Intervention study (featuring random assignment to a year-long attachment-based program designed to enhance parental caregivers’ sensitivity). |

| DePasquale et al., 2018 | 66 children from international orphanages or foster care14 | Toddlers (M=25.0 mos.) (SD=4.6 mos.) All adoptive families reported annual household incomes of at least $40,000, with 5% reporting incomes between $40,000 and $59,000, 32% between $60,000 and $99,000, and the remainder over $100,000. |

Matemal sensitivity | Observation during free play | Baseline Reactivity (SSP) | Salivary cortisol was collected immediately before and then 15 m and 30 m after the SSP. | Children whose adoptive mothers displayed higher levels of sensitivity exhibited larger increases in cortisol in response to the SSP. | Maternal sensitivity was not associated with baseline cortisol levels. |

| Dougherty et al., 2011 | 160 | Preschoolers (M=43.5 mos.) (SD=2.8 mos.) Income not reported. The majority of children were from two-parent, middle-class families. |

Parental hostility (96% mothers) |

Observation during Teaching Tasks battery15 | Baseline Reactivity (Lab-TAB16) | Salivary cortisol was collected at baseline and after a Stranger Approach task (60 m post-baseline), a Transparent Box task (90 m), and a Box Empty task (130 m). | Parental hostility was associated with high and increasing cortisol levels among children whose parents had a history of depression. | This moderating effect was specific to children who were exposed to maternal depression during the first few years of life. |

| Dougherty et al., 2013 | 153 | Preschoolers (M=49.9 mos.) (SD=9.8 wks.) Annual household income ranged from less than $20,000 (7% of the sample) to over $100,000 (36%). |

Maternal hostility and support | Observation during five tasks (a book reading, a guessing game, a maze, a story sequencing task, and a set of puzzles) | Baseline Reactivity (Matching task17) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to the stressor task (after a 30-m quiet play session) and 20, 30, 40, and 50 m following the completion of the matching task. | Maternal hostility moderated the association between maternal depression and reactivity. Children of mothers who had a history of depression during the child’s life and who displayed hostility exhibited increases in cortisol in response to the stressor, while children of mothers without depressive history who displayed hostility exhibited decreases in cortisol. |

|

| Feldman et al., 2010 | 53 mother-infant dyads (randomly assigned to SFP or SFP+T)18 | Infants (M=26 wks.) Income not reported. Mothers had at least a high school education. |

Maternal touch | Observation during SFP or SFP+T | Baseline Reactivity (SFP or SFP+T) | Baseline salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab in the morning. Cortisol samples were collected 20 and 35 m after the SFP or SFP+T procedure |

Cortisol reactivity was higher among infants in the SFP condition relative to those in SFP+T condition. Cortisol decreased at recovery for infants in the SFP+T, but further increased for those in the SFP. |

Myssynchrony was also measured, and indicated the frequencies of maternal stimulatory and proprioceptive touch while the child showed gaze aversion. Myssynchrony was associated with higher cortisol levels among children. |

| Fisher, Serbin, et al., 2007 | 36 | Preschoolers (M=4.8 yrs.) (SD=1.1 yrs.) Median annual household income was $31,725. Fourteen children (35%) came from families with incomes below the Canadian threshold for poverty. |

Maternal emotional support and stimulation | Observation during a 15m task19 | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol samples were collected by mothers upon child wakening, ∼20 m post waking, and again every two hours until child went to sleep at night. | Children of mothers who displayed lower levels of maternal emotional support exhibited lower levels of cortisol ∼20 m post waking. | |

| Fisher, Stoolmiller et al., 2007 | 177 | 3 groups of children20 (M=4.4 yrs.) Median annual household income was between $15,000 and $19,999. |

Maternal consistency and responsiveness | n/a | Diurnal | Early morning and evening salivary cortisol levels were assessed over 12 mos., twice per month. Morning: 30 m after waking Evening: 30 m before bedtime |

Children of foster parents receiving the intervention exhibited patterns of diurnal cortisol comparable to those observed among non-maltreated children by the end of the study. Children of foster parents not receiving the intervention exhibited increasingly ‘flattened’ patterns of diurnal cortisol by the end of the study. |

Intervention study (featuring random assignment to a program designed to teach consistent and responsive parental caregiving behaviors). |

| Fisher et al., 2011 | 71 | Preschoolers (M=4.47 yrs.) Median annual household income was between $15,000 and $19,999. |

Maternal consistency and responsiveness | n/a | Diurnal | Saliva cortisol was collected in the morning and evening on 2 consecutive days each month. Initial collection occurred 3–5 wks. after a placement change Morning: 30 m after waking Evening: 30 m before bedtime |

Placement change was associated with increasingly smaller diurnal declines in cortisol (i.e., higher diurnal cortisol levels) in the regular foster care group. In the intervention foster care group, elevations in diurnal cortisol were not observed. |

Intervention study (featuring random assignment to a program designed to teach consistent and responsive parental caregiving behaviors). |

| Grant et al., 2009 | 88 | Infants (M=37 wks.) (SD=0.76 wks.) Income not reported. Participating mothers were classified as high risk on the basis of a score of 23 or higher on the antenatal risk questionnaire (ANRQ).21 |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation during free play | Baseline Reactivity (SFP) | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab, and 15, 25, and 40 m after the still-face procedure. | Lower levels of maternal sensitivity were associated with higher levels of reactivity. | |

| Gunnar et al., 1996 | 73 | Toddlers (M=18 mos.) Income not reported. Most (85%) mothers held bachelors degrees or higher. |

Maternal responsiveness & attachment security | Observation during the well-baby exam and inoculation. | Baseline Reactivity (Inoculation, SSP) | Salivary cortisol was collected 20 m after inoculation. For SSP, salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab and 25 m following the first separation (10 m following the last reunion). |

At 15 and 18 mos., insecurely attached infants who were also classified as being high on fearfulness were found to display higher cortisol reactivity to inoculation and the SSP At 2 to 6 mos., baseline cortisol levels were significantly lower for securely attached babies. |

|

| Hastings et al., 2011 | 402 | Preschoolers (M=4.01 yrs.) (SD=0.71 yrs.) Income not reported. Highest level of maternal education ranged from high school (22%) to an advanced degree (40%). |

Maternal punishment | Self-report22 | Baseline Reactivity (interactions with unfamiliar adults) | Salivary cortisol was collected ∼20 m after meeting the unfamiliar adults, after interactions with the adults, and again ∼40–60 m after the first sample. | Children of mothers who reported engaging in higher levels of punishment exhibited larger increases in cortisol in response to interactions with unfamiliar adults. | |

| Hertsgaard et al., 1995 | 38 | Toddlers (M=19.3 mos.) Income not reported. |

Attachment security and organization | Observation during free play and the SSP23 | Reactivity (SSP) | Salivary cortisol was collected 30 m after the beginning of first separation episode. | Children classified as disorganized in their attachment exhibited higher levels of cortisol in response to the SSP. | Baseline cortisol levels were not assessed. |

| Hutt et al., 2013 | 9366 | Toddlers (M=24 mos.) Annual household incomes ranged from below $30,000 (7% of the sample) to above $60,000 (50%). |

Maternal protective behavior | Observation during a series of novel tasks24. | Baseline Reactivity (Novel tasks) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to (∼11:30 a.m.) and following (∼1:00 p.m.) the completion of the novel tasks | Higher levels of maternal protective behavior were associated with larger increases in cortisol in response to the novel tasks. | |

| Jansen et al., 2010 | 141 | Infants (M=34.5 days.) (SD=3.7 days.) Income not reported. Most (75%) participants were rated as having a high level of education (not defined). |

Maternal sensitivity and cooperation | Observation during bath | Baseline Reactivity (Bath) | Salivary cortisol was collected within 10 m of researcher’s arrival at the participants’ home, and 25m and 40m after the infant was taken out of the bath. | The quality of maternal caregiving was not associated with either cortisol reactivity or recovery. | |

| Johnson et al., 2018 | 177 | Toddlers (M=15.3 mos.) (SD=2.61 mos.) Over one third (35%) of participants had annual household incomes under 100% of the federal poverty level; an additional 17% had incomes between 100% and 150% of the federal poverty level. |

Attachment security | Observation during child clinic visit (Q-Sort25) | Baseline Reactivity (Inoculation) | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the clinic arrival, immediately following the physical exam before the inoculation, and 20 m post inoculation. | Toddlers rated as insecurely attached and who were from households below 150% of the federal poverty level exhibited significantly higher baseline cortisol than toddlers who rated as securely attached from comparably-impoverished households. Reactivity in response to inoculation did not differ by poverty or attachment security. |

|

| Kaplan et al., 2008 | 47 | Infants (M=4 mos.) Income not reported. Nearly all (93%) mothers had a high school diploma or higher. |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation during free play | Baseline | Salivary cortisol was collected before the free play session between. | Maternal sensitivity moderated the effects of antenatal psychiatric illness on infant baseline cortisol levels. Infants of mothers with a psychiatric diagnosis who displayed low maternal sensitivity exhibited higher baseline cortisol levels. |

Maternal sensitivity was unrelated to cortisol among infants of mothers without a psychiatric diagnosis. |

| Kertes et al., 2009 | 274 | Preschoolers (M=3.97 yrs.) (SD= 0.48 yrs.) Annual household income ranged from less than $25,000 to over $200,000, with a mean of $76,000 – $100,000. |

Parent-child interaction quality (88% of parents were mothers) | Observation during a 30m parent-child interaction (EAS)26 | Baseline Reactivity (Lab-TAB27) | Salivary cortisol was collected after arrival at the lab in the morning (∼ 10:45 a.m.) or afternoon (∼1:15 p.m.), ∼25 m after arrival, ∼20 min after beginning of the Lab-TAB, and ∼ 20 min after the Lab-TAB. | Children who were extremely socially inhibited and who had higher-quality interactions with their parents exhibited smaller elevated in cortisol in response to the Lab-TAB than children who were extremely socially inhibited and had lower-quality interactions with their parents. | The quality of parent-child interaction was unrelated to HPA-axis reactivity among children who were not socially inhibited. |

| Kiel & Kalomiris, 2016 | 99 | Toddlers (M=24.8 mos.) (SD=0.73 mos.) Income not reported. Socioeconomic status as rated on the Hollingshead scale28 ranged from 17 to 66, with a mean of 49.3 (SD=12.3), which corresponds to middle class. |

Maternal comforting behavior | Observation during free play. | Baseline Reactivity (two fear-inducing tasks29) | Salivary cortisol was after the toddler acclimated to the lab (at least 20 m after arrival) and again 20 m after the completion of the second fear-inducing task. | Children of mothers who displayed higher levels of unsolicited or spontaneous comforting behaviors exhibited smaller elevations in cortisol in response to the fear-inducing tasks. | Findings for unsolicited comforting behaviors held after controlling for soliciting comforting behaviors and the level of fear toddlers displayed during the tasks. |

| Kryski et al., 2013 | 160 | Preschoolers (M=3.6 yrs.) (SD= 0.2 yrs.) Income not reported. The mean socioeconomic status as rated on the Hollingshead scale was 46.1 (SD=10.3), which corresponds to middle class. |

Parental positive and negative affect (96% of parents were mothers) | Observation (Teaching Tasks battery30) | Baseline Reactivity (Lab-TAB31 tasks) | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab, 30 min following the Stranger Approach task, 30 min after the Transparent Box task, and 20 min after the completion of the final Lab-TAB task. | Children rated lower on effortful control and whose parents displayed higher levels of positive affect exhibited lower levels of baseline cortisol. Children rated higher on effortful control and whose parents displayed higher levels of positive affect exhibited higher levels of baseline cortisol. Children rated lower on effortful control and whose parents displayed higher levels of negative affect exhibited higher levels of cortisol at baseline and in response to the Lab-TAB tasks. |

Parental negative affect was unrelated to cortisol for children who were not related lower in levels of effortful control. |

| Laurent et al., 2016 | 100 | Toddlers (1–3 years) Income not reported The majority (78%) of mothers had a college degree. |

Maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness | Observation during free play and reunion following the Lab-TAB. | Baseline Reactivity (Lab-TAB) | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab, 15 m after arrival, and 20, 25, and 45 m after the Lab-TAB. | Children whose mothers displayed higher levels of sensitivity exhibited lower levels of cortisol at baseline and in response to the Lab-TAB, as well as more rapid recovery to baseline cortisol levels following the stressor. Children whose mothers displayed higher levels of intrusiveness exhibited slower recovery to baseline cortisol levels following the stressor. |

|

| Laurent et al., 2017 | 73 | Infants (M=6 mos.) Median annual household income was between $10,000 and $19,999. |

Maternal mindfulness | Self-report (IMP-I32) | Baseline Reactivity (SFP) | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab, immediately following the SFP, and again 15 and 30 m after the SFP. | Children of mothers who reported higher levels of mindful parenting behaviors exhibited smaller increases in cortisol in response to the SFP. | |

| Luijk et al., 2010 | 369 | Toddlers (M=14.7 mos.) (SD=0.9 mos.) Income not reported. |

Attachment security and organization | Observation (SSP33) | Diurnal Reactivity (SSP) | To assess diurnal HPA-axis activity parents collected cortisol five salivary cortisol samples during a weekday at home.34 To assess HPA-axis reactivity, salivary cortisol samples were taken prior to the SSP, ∼10 m after the first separation episode, and ∼15 m later. |

Children rated as disorganized exhibited a flattened diurnal pattern of cortisol relative to children who were not rated as disorganized. Children rated as insecure-resistant exhibited larger increases in cortisol in response to the SSP than children who were not rated as insecure-resistant. |

|

| Marceau et al., 2013 | 134 | Children (M age at placement=7.11 days.) (SD=13.3 days.) Median annual household income was less than $15,000 for birth families and between $125,000 and $150,000 for adoptive families. |

Overreactive parenting by adoptive parents | Self-report35 | Variability in diurnal cortisol36 | Salivary cortisol was collected ∼30 m after waking and before bed on three days when children were ∼4.5 yrs. of age. | Children who experienced high levels of prenatal risk (defined as a composite of substance use, depression, and anxiety) and whose adoptive mothers reported engaging in inconsistently-overreactive parenting across age exhibited lower levels of variability in diurnal cortisol. Children who experienced high levels of prenatal risk and whose adoptive fathers reported inconsistent overreactive parenting exhibited higher levels of variability in diurnal cortisol. |

Among children who experienced low levels of prenatal risk there were no associations between inconsistent overreactive parenting and variability in diurnal cortisol. |

| Martinez-Torteya et al., 2014 | 153 | Infants (M=7 mos.) Median annual household income was between $45,000 and $49,999, with over one-quarter of the sample (27%) below $20,000. Seventy-six percent of mothers had a history of childhood maltreatment. |

Maternal positive behaviors, hostility, and overcontrolling behaviors37 | Observation during teaching tasks and free play | Baseline Reactivity (SFP) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to and 20, 40, and 60 m after the SFP. | Children whose mothers displayed higher levels of positive parenting behaviors were less likely to respond to the SFP (response was defined as an increase in cortisol of 10% or more over baseline). Children whose mothers displayed higher levels of hostility were more likely to respond to the SFP. |

|

| Martinez-Torteya et al., 201538 | 167 | Infants & Toddlers (M=7–16 mos.) Median annual household income was between $45,000 and $49,999, with over one-quarter of the sample (27%) below $20,000. Seventy-six percent of mothers had a history of childhood maltreatment. |

Maternal overcontrolling behaviors35 | Observation during teaching tasks and free play | Baseline Reactivity (SFP) | At 7 mos., salivary cortisol was collected prior to and 20, 40, and 60 m after the SFP. At 16 mos., salivary cortisol was collected prior to and 20, 40, and 60 m after the SSP. |

Maternal overcontrolling behaviors were associated with higher levels of baseline cortisol and reactivity. | Infants exhibited a cortisol response to the SSP at 16 mos., but not to the SFP at 7 mos. |

| Mills-Koonce et al., 201139 | 717 | Infants (M=7.4 mos.) (SD=1.3 mos.) Mean income-to-needs ratio was 2.39 (SD=1.85) Toddlers (M=24.6 mos.) (SD=1.6 mos.) Mean income-to-needs ratio was 2.34 (SD=1.69) |

Paternal sensitivity40 and negativity41 | Observation (Infancy: free play) (Toddlerhood: puzzle task) |

Baseline Reactivity (Infancy42) (Toddlerhood43) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to challenge tasks, 20 m after the children’s peak emotional arousal, and 40 m after peak arousal. | Higher levels of paternal negativity were associated with higher levels of cortisol reactivity in infancy and higher overall levels of cortisol in toddlerhood. | Paternal sensitivity was not found to be associated with child cortisol levels. Paternal caregiving behaviors during infancy did not independently predict later cortisol activity during toddlerhood. |

| Morelius et al., 2007 | 22 | Infants (M=10 wks.)44 Income not reported. For approximately half the sample (55%) the highest level of maternal education was elementary school. For the remainder (45%) it was high school. |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation | Baseline Reactivity (Diaper change) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to and 30 min after a diaper change. | Maternal sensitivity was not related to baseline cortisol levels or reactivity to diaper change. | |

| Nachmias et al., 1996 | 77 | Toddlers (M=18 mos.) Income not reported. Maternal education ranged from 12 to 21 years, with a mean of 15.8 years. |

Attachment security and organization | Observation during the SSP | Baseline Reactivity | Salivary cortisol was collected upon arrival at the lab and ∼45 m after the beginning of the test session. | Elevations in cortisol were found only for inhibited toddlers in insecure mother-child attachment relationships. | |

| Pendry & Adam, 2007 | 32 | Kindergarteners (M=6.1 yrs.) Income not reported. |

Maternal involvement and warmth | Self-report (IPPA45) | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected at home immediately upon waking and just prior to bed on two consecutive days. | Children of mothers who displayed higher levels of involvement and warmth exhibited steeper declines in cortisol over the course of the day. | Maternal involvement and warmth were not associated with children’s waking cortisol levels or overall levels of cortisol. |

| Philbrook & Teti, 2016 | 82 | Infants Time 1 (M=3.1 mos.) Time 2 (M=6.1mos.) Time 3 (M=9.2 mos.) Annual household income ranged from $9,500 to $300,000 with a median of $65,000. |

Maternal emotional availability | Observation during bedtime (EAS46) | Nocturnal | Salivary cortisol was collected at 3, 6, and 9 mos. of child age just before the infant fell asleep and again upon waking the next morning. | Infants of mothers who displayed lower levels of emotional availability exhibited higher cortisol levels at bedtime at each age. Infants of mothers who responded more often to their non-distressed cues exhibited lower overall cortisol levels at each age. Infants of mothers who displayed higher levels of emotional availability exhibited low and stable nocturnal levels of cortisol. |

|

| Philbrook et al., 201447 | 167 | Infants Time 1 (M=1 mo.) Time 2 (M=3 mos.) Annual household income ranged from $9,500 to $300,000 with a median of $65,000. |

Maternal emotional availability | Observation (EAS)48 during free play and at bedtime | Nocturnal | Salivary cortisol was collected 3 times across the evening and following morning. The first sample was taken before dinner, the second just before the infant fell asleep, and the third sample when the infant awoke in the morning. |

At T2, over half of the infants in the sample showed patterning49 in their cortisol across the night. At T2, infants of mothers exhibiting higher levels of emotional availability displayed lower cortisol at bedtime and lower overall levels of cortisol (as measured by the AUCG) and smaller increases in cortisol from baseline (AUCI).50 |

At T1, there were no significant differences in cortisol patterning across time with respect to maternal emotional availability at bedtime. At T2, higher levels of emotional availability were associated with a tendency for infants to show a decrease in cortisol across time at the trend level. |

| Rappolt-Schlichtman et al., 2009 | 60 | Toddlers and Preschoolers (Range=2 – 4 yrs.) Most children (unspecified proportion) were from families living below or near the federal poverty level. |

Child conflict with parents and teachers | Parent-child conflict: CPRS51 Teacher-child conflict: STRS |

Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected four times in the morning on two days when children were in care: one day when they were in small groups, and another when they were engaged in normal classroom activities. Sample 1: 9:20 a.m.52 Range=8:30–10:15 a.m. Sample 2: 10:20 a.m. Range=9:20–11:25 a.m. Sample 3: 11:10 a.m. Range=9:45 a.m.-12:25 p.m. Sample 4: 12:15 p.m. Range=11:25 a.m.-1:00 p.m. |

Cortisol levels decreased from the first to the third sample, and then increased from the third to the fourth sample. Children whose mothers reported higher levels of conflict exhibited more gradual declines in cortisol over the course of the day. |

|

| Roque et al., 2012 | 51 | Toddlers (M=21.3 mos.) (SD=1.96 mos.) Income not reported. Maternal education ranged from 9 to 19 years, with a mean of 15.2 years (SD=3.04) |

Attachment security and organization | Observation during mother-child interaction (AQS53) | Baseline Reactivity (Emotion Regulation Paradigm54) | Salivary cortisol was collected immediately before and 30 m after each episode of the emotion regulation paradigm. | Secure children showed significant increases in their cortisol levels after fear episodes and significant decreases after positive affect ones. Insecure children did not show significant differences in cortisol levels in any of the episodes. |

No significant changes were found for frustration/anger episodes. |

| Schieche & Spangler, 2005 | 76 | Infants & Toddlers Time 1 (M=12.4 mos.) Time 2 (M=22.4 mos.) Income not reported. Twelve percent of children were from lower class families, where class was defined as a composite of household income, paternal education, and paternal occupation. |

Attachment security and organization; maternal supportive behaviors | Observation during SSP55 and problem-solving tasks56 | Baseline Reactivity (problem-solving tasks) | Salivary cortisol was collected immediately before the problem-solving tasks and then 15 and 30 m after the task. | Among toddlers rated as behaviorally inhibited, response to the problem-solving task differed as a function of attachment classification: securely-attached toddlers exhibited a significant decrease in cortisol in response to the problem-solving task; comparable decreases were not observed among toddlers classified as insecure-ambivalent or disorganized. | Maternal supportive behaviors were not associated with children’s response to the problem-solving task. |

| Spangler et al., 1994 | 41 | Infants (3, 6, 9 mos.) Income not reported. Over one-quarter (27%) of children were from families rated lower class based on paternal education, occupation, and income. |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation during free play | Baseline Reactivity (Free play, diaper change57). | Salivary cortisol was collected before the play session, 15 m after free play session and 10 m after diaper change. | At 9 mos., infants of highly insensitive mothers had higher baseline cortisol levels. Cortisol increased significantly for infants with highly insensitive mothers at 3 mos. and 6 mos., but not at 9 mos. |

|

| Sturge-Apple et al., 2012a | 201 | Toddlers (M=27 mos.) Median annual household income was $18,300 and nearly all children were from families (99.5%) living at or below the federal poverty level. |

Maternal emotional unavailability | Maternal report Observation during free play and a compliance task58 |

Baseline Reactivity (SSP, SPAT59) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to the SSP and ∼25 and 50 m after the 5th episode. Cortisol was also collected prior to and ∼25 and 37 m after the SPAT. |

Maternal emotional unavailability was negatively associated with cortisol change in response to the SSP. Maternal emotional unavailability predicted higher baseline cortisol levels on the day of the SSP. Maternal emotional unavailability was not significantly associated with baseline cortisol or cortisol reactivity the SPAT task. |

|

| Sturge-Apple et al., 2012b | 201 | Toddlers (M=27 mos.) Median annual household income was $18,300 and nearly all children were from families (99.5%) living at or below the federal poverty level. |

Maternal harsh parenting (harsh, angry, critical, disapproving and/or rejecting behavior). | Maternal report Observation during free play and a compliance task60 |

Basal | Salivary cortisol was collected upon children’s arrival at the laboratory in the morning (∼9:30 a.m.) | Children of mothers who displayed higher levels of harsh parenting exhibited higher levels of baseline cortisol, but only if they were classified as belonging to the dove profile.61 | |

| Taylor et al., 2013 | 148 | Toddlers, Preschoolers, & School-Aged Time 1 (T1) (M=18 mos.) Time 2 (T2) (M=30 mos.) Time 3 (T3) (M=72 mos.) Income not reported. |

Maternal intrusive and over-controlling parenting | Observation (T1: free play) (T2: teaching paradigm task62, a clean-up task63) |

Baseline Reactivity (Not-sharing task64) | Salivary cortisol was collected at T3, prior to the not-sharing task, 10 m after the task, and 20 m after the task | Intrusive-overcontrolling parenting at T2 predicted higher levels of children’s cortisol at T3. | |

| Thomas et al., 2017 | 272 | Infants (M=6 mos.) A small portion of the sample (9%) had annual household incomes of less than $40,000. |

Mother-infant interaction quality | Observation while mothers taught their child a new task (PCITS65) | Baseline Reactivity (Lab-TAB66) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to and 20 m following the Lab-TAB. | Higher mother-infant interaction quality was associated with smaller increases in cortisol in response to the Lab-TAB. | Interaction quality mediated the effects of perceived social support in pregnancy. |

| Thompson & Trevathan, 2008 | 63 | Infants (M=13.2 wks.) (SD=0.84 wks.) Income not reported. Nearly one-third of the sample (31%) indicated that they face substantial financial stress.67 |

Maternal sensitivity | Observation during normal interaction68 | Baseline Reactivity (maternal separation69) | Salivary cortisol was collected prior to and ∼20–30 m following initial separation. | Maternal sensitivity was not related to infants’ response to maternal separation. | |

| Thompson et al., 2018 | 306 | Preschoolers (M=37 mos.) (SD=0.84 mos.) Over one-quarter (29%) of children were from families with annual household incomes below or near the federal poverty level, while an additional 27% had incomes below the median. |

Maternal warmth, negativity, limit setting, scaffolding, and responsiveness | Observation during mother-child interaction70 | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected twice a day (∼30 m after waking and ∼30 m before bed) on three consecutive days beginning when children were 36–40 mos. (T1) and at 9-mo. intervals thereafter (T2: 44–49 mos.; T3: 53–58 mos.; T4: 62–67 mos.) | Children of mothers who displayed stable (over time), higher levels of negativity exhibited lower levels of morning cortisol over time; children of mothers who displayed stable, higher levels of scaffolding exhibited higher levels of morning cortisol over time. Children of mothers who exhibited stable, higher levels of negativity and lower levels of responsiveness exhibited a flattened diurnal slope across ages. |

|

| Van Bakel & Riksen-Walraven, 2004 | 85 | Toddlers (M=15.1 mos.) (SD=0.25 mos.) Income not reported. |

Attachment security and organization. | AQS71 | Baseline Reactivity (SSP) | Salivary cortisol was measured prior to and 3 m after the SSP. | More secure maternal-child attachment was associated with larger increases in cortisol in response to the SSP. | |

| Zalewski et al., 2012a | 78 | Preschoolers Time 1 (T1) (M=36.6 mos.) Time 2 (T2) (M=42.0 mos.) Annual household income ranged from less than $20,000 to over $100,000, with 18% of the sample at or below the federal poverty level. |

Maternal warmth, responsiveness, scaffolding, limit setting, and negative affect. | Observation at T1 during three tasks (restricted play, free play, Lego-building task) | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected by at home in the morning and evening on two subsequent days. Morning: 30 m after waking Evening: 30 m before bedtime |

Higher levels of maternal negativity were associated with a higher likelihood that children would exhibit a blunted pattern of diurnal cortisol. Children whose mothers displayed higher levels of warmth were less likely to demonstrate a blunted pattern of diurnal cortisol. |

Maternal warmth and negativity mediated the associations between poverty and blunted cortisol at T2. |

| Zalewski et al., 2012b | 306 | Preschoolers (M=37.0 mos.) (SD=0.84 mos.) Nearly one-third of children came from households with annual household incomes at or below 150% of the federal poverty level. |

Maternal warmth, responsiveness, scaffolding, limit setting, and negative affect. | Observation during three tasks (restricted play, free play, Lego-building task) | Diurnal | Salivary cortisol was collected at home in the morning and evening on three subsequent days. Morning: 30 m after waking Evening: 30 m before bedtime |

Higher levels of maternal warmth were associated with higher levels of morning cortisol. Higher levels of maternal responsiveness were associated with steeper diurnal declines in cortisol, whereas higher levels of negativity were associated with flatter diurnal patterns. |

|

Note that the sample employed in this study was the same as the sample employed by Albers et al. (2008).

Video-Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD; Van Zeijl et al., 2006)

Strange Situation Paradigm (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

The sample for this study was drawn from the Family Life Project (FLP), as were the samples by Berry et al. (2014, 2016), Blair et al. (2008, 2015), Blair, Granger et al. (2011), Blair, Raver et al. (2011), and Mills-Koonce et al. (2015).

Three tasks: a mask presentation challenge, a barrier challenge, and an arm restraint challenge.

Two tasks: a toy removal challenge and a mask presentation challenge.

Sensitivity, detachment, positive regard, animation, and stimulation.

Intrusiveness and negative regard.

Some mothers used emotional withdrawal as a disciplinary tactic; others were withdrawn due to depression. Groups were combined for analysis.

Conflict tactics scale (CTS; Straus, 1979)

Strange Situation (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

80% of children had experienced institutional care.

Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1995), from which 12 tasks were selected.

This task was developed by Kryski and colleagues (2011) and is based on a modified version of Lewis and Ramsay’s (2002) matching task.

Conventional Still-Face Paradigm (SFP; Tronick, Als, Adamson, Wise, & Brazelton, 1978), or altered Still-Face Paragraph with touch (SFP+T).

Mothers and children were asked to work together on a series of difficult puzzles and games (Saltaris & Samaha, 1998)

Foster children were divided into two groups, and of which was assigned to the intervention. Third group were control children residing with their families.

The Parenting Scale (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993) and Parenting Dimensions Inventory (Power, 1993) were used for Sample 1. Child Rearing Practices Report (Block, 1981) and Responses to Children’s Emotions (Hastings & De, 2008) were used for Sample 2. Parenting Styles & Dimensions Questionnaire (Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 2001) were used for Sample 3.

Strange Situation Paradigm (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

A stranger approach task, a stranger working task, clown, puppet show, robot, and spider tasks.

Q-Sort (Waters & Deane, 1985).

Emotional Availability scales (EAS; Biringen, Robinson & Emde, 1998).

Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB tasks; Gold-smith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley & Prescott, 1995).

Hollingshead’s Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975)

Including a Clown and a Spider episode (see Kiel & Buss, 2012).

Teaching Tasks battery (Egeland, Weinfield, Hiester, Lawrence, Pierce & Chippendale, 1995) included book reading, block building, naming objects with wheels, matching shapes, completing a maze using an etch-a-sketch, and gift presentation.

Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB tasks; Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley & Prescott, 1995).

Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting – Infant Version (Duncan, 2007).

Strange Situation Paradigm (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

Samples were collected upon waking, 30 m after waking, between 11 am and 12 pm, between 3 and 4 pm, and at bedtime.

Using a subscale of the Parenting Scale (Arnold et al., 1993) at 9, 18, 27 mos. and 4.5 yrs. of child age.

Cortisol variability measures the extent to which an individual’s cortisol deviated from its usual diurnal pattern. It is operationalized as the residual cortisol circulating in the system after accounting for individual-specific diurnal declines.

Assessed using the MACY infant-parent coding system, (Earls, Beeghly, & Muzik, 2009).

This study employed a super-set of the sample reported on in Martinez-Torteya et al. (2014).

Used a sub-set of the FLP sample (fathers) also used by Berry et al. (2014, 2016, 2017) Blair et al. (2008, 2015), Blair, Granger et al. (2011), and Blair, Raver et al. (2011).

Sensitivity, detachment (reverse-coded), stimulation, positive regard, and animation.

Intrusiveness and negative regard.

Three tasks: a mask presentation challenge, a barrier challenge, and an arm restraint challenge.

Two tasks: a toy removal challenge and a mask presentation challenge.

At age of first assessment.

Measures for parental involvement was designed for the purposes of this study, and warmth was measured by the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987)

Emotional availability scales (Biringen, Robinson, Emde, 1998).

Used a super-set of children employed in Philbrook & Teti (2016).

Emotional availability scales (Biringen, Robinson, Emde, 1998).

A decline in cortisol from late afternoon to bedtime, a gradual increase overnight, and sharp increase in the morning post-awakening were theorized to mark the presence of a nocturnal rhythm in infant cortisol.

AUCG: Area under curve with respect to ground; AUCI: area under curve with respect to increase.

Child-Parent Relationship Scale (Pianta, 1992).

Times reported for each sample correspond to approximate time that sample was collected.

The Attachment Behavior Q-set (AQS, Waters, 1995).

Emotion Regulation Paradigm consists of three episodes: Fear, Positive Affect, and Frustration/Anger (Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999).

Strange Situation Paradigm (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

The toddlers’ task-solving German versions of the 7-point scales, supportive presence and quality of assistance was developed by Matas et al. (1978).

At 6 and 9 mos., one saliva collection took place at participant’s home, the rest in the lab.

The Iowa family interaction rating scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001)

Simulated Phone Argument Task (SPAT; Davies, Cummings, & Winter, 2004)

The Iowa family interaction rating scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001)

Profile classifications were made in accordance with Korte’s evolutionary model of temperament (Korte, Koolhaas, Wingfield, & McEwen, 2005), based on children’s temperament as rated by maternal report and coding of emotional response to four unfamiliar episodes. Children classified as doves were rated by their mothers as higher on falling reactivity and exhibited higher levels of inhibition, avoidance, and vulnerable affect in response to the unfamiliar episodes.

Adapted from Calkins & Johnson, 1998

Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1995. In this task, children played a card game with an experimenter that involved candy being unfairly divided based on what cards they received.

Parent Child Interaction Teaching Scale (PCITS; Oxford & Finlay, 2013).

Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB tasks; Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1996).

13% indicated they “do not have enough money to meet basic needs” and 18% that they “barely pay the bills but manage on my own.”

A coding system developed by Isabella and Belsky (1991).