Abstract

Introduction

Current pharmacological treatment options for hyperemesis gravidarum have been introduced based on scarce evidence and are often not sufficiently effective. Several case reports suggest that mirtazapine, an antidepressant, may be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum, but so far there are no controlled trials investigating the potential effect of mirtazapine on hyperemesis gravidarum. The antiemetic ondansetron is currently widely used to treat hyperemesis gravidarum despite sparse evidence of effect in pregnant women. This study aims to investigate the effect of mirtazapine on hyperemesis gravidarum while also providing data on the effect of ondansetron.

Methods and analysis

This randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial will be conducted in eight Danish hospitals. One hundred and eighty pregnant women referred to secondary care for hyperemesis gravidarum will be randomly allocated to 14-day treatment with either mirtazapine, ondansetron or placebo. Main inclusion criterion will be Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE-24) score ≥13 or PUQE-24 score ≥7 if accompanied by weight loss >5% of pre-pregnancy weight or hospitalisation. Participants are eligible regardless of whether other antiemetics, including ondansetron, have been tried. The coprimary outcomes are effects of mirtazapine and ondansetron, respectively, on PUQE-24 score tested hierarchically on day 2 and day 14. Secondary outcomes include, but are not limited to, differences between the three groups in number of daily vomiting episodes, dropout due to treatment failure, use of rescue medication, weight change and side effects.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial has been approved by the Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics in the Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Medicines Agency and the Danish Data Protection Agency. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and submitted to relevant conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: clinical trials, maternal medicine, obstetrics, gynaecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First controlled trial testing the effect of mirtazapine in hyperemesis gravidarum.

First placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of oral ondansetron in hyperemesis gravidarum.

Simple study design with relevance to clinical practice.

Patient involvement in protocol development and patient reported outcomes.

Only patients able to tolerate oral medication can be included; thus, the most severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum may be excluded from participation.

Introduction

Hyperemesis gravidarum is one of the leading causes of hospitalisation in pregnancy1 and current treatment options are used despite sparse evidence of effect.

While nausea and vomiting in pregnancy is common and most often not severe, 0.3%–3.6% of pregnant women experience a debilitating level of symptoms.2 This condition, hyperemesis gravidarum, is characterised by severe nausea and vomiting, but diagnostic criteria vary.3 It may cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, weight loss and hospitalisation. It is associated with maternal and neonatal morbidity, lower quality of life and can lead to elective termination of pregnancy.4–7

Recommendations on pharmacological treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum are largely based on knowledge obtained from general antiemetic treatment with scarce evidence on effect and side effects in pregnant women. A Cochrane review from 2017 on interventions for treating hyperemesis gravidarum found a limited number of placebo-controlled trials.8

In most developed countries, including Denmark, no drugs have been approved as treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum or nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Thus, when needed, pharmacological treatment is used off-label.

Ondansetron, a short-acting 5-HT3 antagonist, is one of the most commonly used antiemetics in pregnancy. In 2014, 22.2% of pregnant women in the USA were treated with antiemetics, and of these the majority (89%) used oral ondansetron (19.7% of the pregnancies).9 There are few controlled trials with oral ondansetron and active comparators10 11; however, there are no placebo-controlled trials that have investigated oral ondansetron for hyperemesis gravidarum or nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

Furthermore, ondansetron and other current pharmacological treatment options do not consistently provide symptom resolution. Accordingly, treatment with intravenous fluids is common and in rare cases parenteral nutrition is needed.12

Mirtazapine, an appetite stimulating and antiemetic antidepressant, may be a promising candidate in the clinical management of hyperemesis gravidarum. The pharmacological profile resembles that of a long-acting 5-HT3 antagonist combined with a sedating antihistamine.13 Mirtazapine is described in 23 case reports as an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum,14–22 and the antiemetic effect is confirmed in a systematic review and meta-analysis on mirtazapine for postoperative nausea and vomiting.23 However, there are no controlled trials with mirtazapine in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum.

The aim of this trial is to investigate the effect of mirtazapine and ondansetron on nausea and vomiting in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

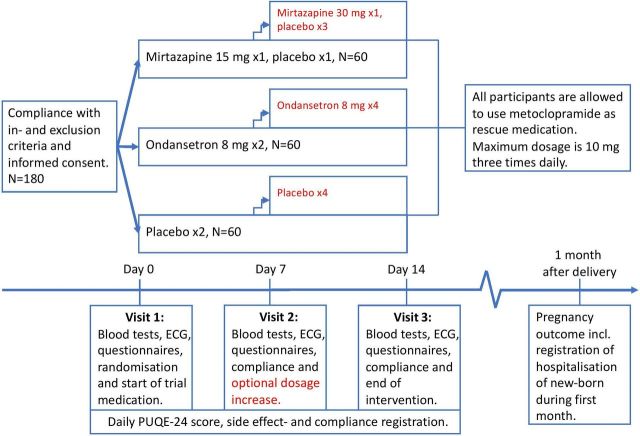

This is a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial conducted in eight Danish hospitals. We plan to randomise 180 participants 1:1:1 to oral treatment with either mirtazapine, ondansetron or placebo. The intervention proceeds for 2 weeks and all participants are allowed to use metoclopramide as rescue medication. Trial design is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial design.

Eligibility

Participants are recruited among patients referred to secondary care in departments of gynaecology and obstetrics. To be eligible, participants must have Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE-24) score ≥13 or PUQE-24 score ≥7 if accompanied by (1) weight loss >5% of pre-pregnancy weight and/or (2) hospitalisation due to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy or hyperemesis gravidarum. The PUQE-24 score is a validated score to grade the severity of HG. It ranges 3–15 with scores ≥13 representing hyperemesis gravidarum24 (see table 1).

Table 1.

Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE-24) scale

| PUQE-24 scoring system | ||||

| In the last 24 hours, for how long have you felt nauseated or sick to your stomach? | ||||

| Not at all (1 point) |

1 hour or less (2 points) |

2–3 hours (3 points) |

4–6 hours (4 points) |

More than 6 hours (5 points) |

| In the last 24 hours have you vomited or thrown up? | ||||

| 7 or more times (5 points) |

5–6 times (4 points) |

3–4 times (3 points) |

1–2 times (2 points) |

I did not throw up (1 point) |

| In the last 24 hours how many times have you had retching or dry heaves without bringing anything up? | ||||

| Not at all (1 point) |

1–2 times (2 points) |

3–4 times (3 points) |

5–6 times (4 points) |

7 or more times (5 points) |

| PUQE-24 score: mild ≤6, moderate 7–12, severe ≥13 | ||||

| On a scale of 0 to 10, how would you rate your well-being? 0 (worst possible) 10 (the best you felt before pregnancy) | ||||

PUQE-24, Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis.

Full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

PUQE-24, Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis.

Both inpatients and outpatients are eligible and can be recruited on first or subsequent admissions. Participants are eligible regardless of whether other antiemetics, including ondansetron, have been tried, and concomitant use of first-line treatment (pyridoxine and antihistamine) is allowed and will be registered. ECG and blood tests must be performed before final decision of inclusion to rule out long QT syndrome and elevated creatinine or alanine aminotransferase.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation and manufacturing of trial medication is performed by Glostrup Pharmacy (Glostrup, Denmark). Both ondansetron and mirtazapine are encapsulated and appear similar to placebo in regard to look, taste and smell. Randomisation is computerised via randomization.com creating a unique randomisation number for each treatment unit. Randomisation is performed in blocks of 3 or 6 and stratified according to study site. The study sites receive the trial medication blinded. Each new participant is provided with the trial medication with the lowest available randomisation number at that specific study site.

The randomisation lists are held by Glostrup Pharmacy until the end of the trial.

Interventions

The intervention proceeds for 14 (±1) days as either inpatient or outpatient.

All trial medications are oral tablets and administration of trial medication starts at bedtime of the day of randomisation (visit 1 on day 0). During week 1, trial medication is administered at bedtime and in the morning. If a participant vomits within 45 minutes after administration, one readministration is encouraged.

During the first week, the bedtime administration in the mirtazapine group contains mirtazapine 15 mg and the morning administration contains placebo. In the ondansetron group, both morning and bedtime administrations contain ondansetron 8 mg, whereas in the placebo group, morning and bedtime administrations contain placebo.

In case of insufficient symptom relief, an increase in dosage is optional at visit 2 on day 7 (±1). If desired, the number of administrations in week 2 is increased to four daily with administrations in the morning, at lunch, late afternoon and bedtime.

In case of dosage increase, the bedtime administration in the mirtazapine group contains mirtazapine 30 mg and the administrations in the morning, at lunch and late afternoon contain placebo. In the ondansetron group, all four administrations contain ondansetron 8 mg, and in the placebo group, all four administrations contain placebo.

If dosage increase is not desired, the treatment regimen in the first week (week 1) continues in the second week (week 2).

Administration of metoclopramide as rescue medication is allowed for all participants in case of insufficient symptom relief as is treatment with intravenous fluids according to local procedures. All participants will be instructed to take a vitamin B supplement daily containing 15 mg thiamine, 15 mg riboflavin and 15 mg pyridoxine.

The intervention ends on day 14 (±1).

Study procedures

Participation in the trial includes three visits of approximately 30–45 min each.

After obtainment of written informed consent, trial specific procedures can be performed to assess possible unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria. This might include renewed ultrasound scan to confirm viable singleton pregnancy, ECG and blood tests to rule out long QT-syndrome and elevated creatinine and alanine aminotransferase. Obstetric history and concomitant medications including all medications administered during current pregnancy are recorded, and participants undergo a physical examination.

Visit 1 (day 0) takes place before any administration of trial medication and may take place on the same day as informed consent and assessment of eligibility criteria. At this visit, baseline data are collected including patient reported outcomes which are filled in to online questionnaires by participants (please refer to table 3). Participants are weighed and vital signs are measured. Blinded trial medication is dispensed and participants are instructed to start administration of trial medication on the evening of the day of visit 1. Likewise, participants are instructed to administer the dispensed vitamin B daily and metoclopramide if needed. Participants are instructed to fill out daily online questionnaires during the intervention.

Table 3.

Trial schedule—outcomes (pro: patient-reported outcomes)

| Visit 1 Day 0 Randomisation |

Visit 2 Day 7 (±1) |

Visit 3 Day 14 (±1) End of intervention |

Daily online questionnaires | 1 month after delivery | |

| PUQE-24 score | PRO | PRO | PRO | PRO | |

| PUQE well-being score | PRO | PRO | PRO | PRO | |

| Nausea VAS | PRO | PRO | PRO | PRO | |

| Daily vomiting episodes | PRO | PRO | PRO | PRO | |

| Administration of trial medication | PRO | ||||

| Administration of rescue medication | PRO | ||||

| Side effects | Registered by trial personnel | Registered by trial personnel | Registered by trial personnel | PRO | |

| NVPQOL | PRO | PRO | PRO | ||

| HELP-score | PRO | PRO | PRO | ||

| EQ5D-5L | PRO | PRO | PRO | ||

| Modified PSQI | PRO | PRO | PRO | ||

| Patient satisfaction with treatment VAS | PRO | PRO | |||

| Patient consideration of termination of pregnancy | PRO | PRO | PRO | ||

| Request for dosage increase | Registered by trial personnel | ||||

| Request for continued treatment | Registered by trial personnel | ||||

| Days on sick leave | PRO | PRO | |||

| Intravenous fluid therapy | PRO | PRO | |||

| Days of hospitalisation | PRO | PRO | |||

| Weight | Measured by trial personnel | Measured by trial personnel | Measured by trial personnel | ||

| Pregnancy outcome including possible malformation and hospitalisation of the new-born | Collected from medical record | ||||

| Treatment failure | Registered by trial personnel at time of event | ||||

PUQE, Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis; VAS, visual analogue score.

At visit 2 (day 7 (±1)), participants again fill out online questionnaires on patient-reported outcomes. Weight and vital signs are measured, and changes in concomitant medication are registered, compliance is assessed, and participants are asked if they experienced other side effects than those registered in the daily online questionnaires, and dosage increase is offered in case of insufficient symptom relief. New trial medication is dispensed, and next visit is scheduled.

At visit 3 (end of intervention on day 14 (±1)), patient-reported outcomes are again recorded via online questionnaires. Weight and vital signs are measured, and changes in concomitant medication are recorded and compliance assessed. Participants are asked if they experienced other side effects than those registered in the daily online questionnaires, and if they desire to continue treatment after the intervention, unblinding of the specific participant is possible. Thereafter, no effect measures are collected, but daily registration of side effects continues until 5 days after end of intervention.

For all participants, blood samples and ECG are collected before randomisation and at visit 2 and 3 to confirm compliance with eligibility criteria. Blood samples from visit 2 and 3 are kept for plasma-mirtazapine and plasma-ondansetron analysis after the end of the trial. Blood samples from visit 1 and 3 are kept for future research.

After pregnancy, delivery and pregnancy outcome as well as possible hospitalisation of the newborn are registered.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the patient-reported outcome PUQE-24 score which is collected in online questionnaires filled in by participants on day 2 and day 14. Differences between baseline values and values recorded during or at end of intervention will be compared.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes mainly include patient-reported outcomes but also outcomes registered by trial personnel.

All outcomes including timings are listed in table 3.

Questionnaires

The online questionnaires at visit 1, 2 and 3 include PUQE-24 score, nausea visual analogue scale (VAS), number of daily vomiting episodes, Health-Related Quality of Life for Nausea and Vomiting during Pregnancy (NVPQOL), Hyperemesis Level Prediction (HELP), health related quality of life (EQ5D-5L), modified Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and a question on consideration of termination of pregnancy. At visit 2 and 3, questionnaires also include satisfaction-with-treatment VAS, number of days on sick leave, hospitalisation and number of intravenous fluid treatments. The questionnaires take approximately 15 min to fill out.

The daily online questionnaires are less extensive and include PUQE-24 score, nausea VAS, number of daily vomiting episodes, registration of side effects and administration of trial and rescue medication. These can be filled out in 2–5 min.

Side effects

Participants are prompted to register side effects in the daily online questionnaires. Moreover, participants will be asked about side effects at visit 2 and 3, and trial personal register further side effects.

Treatment failure

If a participant withdraws from the trial before the end of the intervention, the reason for withdrawal is registered. If the reason is insufficient antiemetic effect of the trial medication, treatment failure is registered as reason for withdrawal and time of treatment failure is recorded.

Pregnancy outcome

Pregnancy outcome include registration of whether the pregnancy resulted in live birth, loss of or termination of pregnancy, mode of delivery, complications, birth weight, gestational age at birth, APGAR score, umbilical cord pH, weight of the placenta, sex of the newborn, congenital malformations and hospitalisation of the newborn during the first month postpartum.

Data collection

The secure browser-based system REDCap (REDCap Consortium, Vanderbilt University, USA) is used as data collection tool.25 All patient-reported outcomes are recorded directly in REDCap by participants filling out online questionnaires via secure email links. Data registered by trial personnel at the visits are entered directly in REDCap. Data on pregnancy and delivery outcome are collected from participant’s and newborn’s medical records and entered in REDCap.

Monitoring

The trial is subject to ongoing monitoring by the Danish units for Good Clinical Practice (GCP-units, https://gcp-enhed.dk/en/gcpunits/) in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP).

Statistical analysis

Sample size

The trial is dimensioned to detect a difference of 2 or more in the coprimary outcomes; change in PUQE-24 score from baseline to day 2 in the mirtazapine versus the placebo group, or in the ondansetron versus the placebo group. Each hypothesis for coprimary outcomes will be tested at significance level 2.5% in order to obtain at family-wise type I error of 5% based on a Bonferroni correction. The power calculation is based on a standard deviation of change in PUQE-24 score of 3, which is a conservative estimate based on a placebo-controlled trial with doxylamine-pyridoxine.26 Expecting dropout of 35%, 58 participants are required in each of the three groups to obtain a power of 80%. Rounding that up to 60 participants, we aim to include 180 participants in total.

Planned analysis

The primary analysis will consist of a linear model with intervention group and baseline PUQE-24 score as covariates adjusted for site due to the stratified design. Intention to treat analysis will be performed where participants will be included in the analysis irrespectively of their adherence to the protocol. Primary and secondary outcomes will be tested hierarchically to control the family-wise error rate.

Significance of the primary outcome will be assessed by comparing differences in PUQE-24 score from baseline to day 2 in the mirtazapine versus the placebo group and similarly in the ondansetron versus the placebo group. If significance is obtained at day 2, a subsequent analysis will be performed at day 14. Difference between mirtazapine and ondansetron will be compared as part of the hierarchical testing if mirtazapine is significantly different from placebo.

The treatment effect for the primary outcomes will be presented as the mean difference between the groups in PUQE-24 score change from baseline to day 2 from baseline to day 14, respectively. Results will be reported with 95% CI.

Subgroup analyses will be performed by stratifying on the baseline variables PUQE-24 score, number of daily vomiting episodes, gestational age and concomitant medication with first-line treatment.

Per protocol analysis including only participants who completed the intervention will be performed as well as sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation where the imputation model will include all available baseline variables.

There are no planned interim analyses.

The statistician performing the analyses will remain blinded until the analysis results are closed.

Patient and public involvement

Representatives from Danish and English hyperemesis gravidarum patient organisations were consulted in the development of the trial and reviewed the protocol. They provided valuable insight which led to considerations of ethical issues as well as feasibility, which resulted in changes in inclusion criteria, outcome measures and option of continued treatment after end of intervention. The trial is considered a priority by the Danish Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology’s Multicentre Consortium, whom are supporting the trial. We plan to inform the trial participants of the final results if requested.

Discussion of design

Relevance

This is the first controlled trial to test mirtazapine as treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum and it is to our knowledge the first trial to test oral ondansetron for hyperemesis gravidarum and nausea and vomiting in pregnancy in a placebo-controlled setting. While the individual participants may not directly benefit from participating in the trial, the trial will provide data on the effect of mirtazapine; a new and possibly more effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum which may reduce the burden of this debilitating condition. Furthermore, data from this trial will fill a knowledge gap on the effect of ondansetron; a commonly used treatment introduced despite sparse evidence of effect in pregnant women.

Safety

Pregnant women are not regularly included in medical trials and a central concern has been an assessment on whether the trial medications are safe to use in early pregnancy.

Based on the reviewed literature with more than 2000 mirtazapine exposed pregnancies (presumably prescribed on the indication depression or anxiety), we consider the use in pregnancy safe.27–31

A systematic review of ondansetron exposure in pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations conclude that the overall risk of congenital malformations is low, but results on risk of oral clefts and cardiac malformations are conflicting.32 However, two recent cohort studies, one including almost 90 000 pregnancies exposed to prescription ondansetron and one including over 23 000 pregnancies exposed to intravenous ondansetron, did not find an association between exposure and cardiac or general congenital malformations in the newborn. They did, however, find that exposure was associated with a small increased risk of oral cleft (3 in 10 000).33 34 Considering this relatively small increased risk and the fact that ondansetron is already being used in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum, compared with the risk of severe hyperemesis gravidarum, we find it ethically acceptable to randomise participants to treatment with ondansetron. All participants are informed about the risk of oral cleft.

Assessment of adverse events is carried out throughout the trial. The trial investigator will assess severity and relation to trial medication. Serious adverse events will be reported to the sponsor, monitor and relevant authorities.

Allocating patients to placebo treatment

Randomising to treatment with placebo in patients suffering from this serious condition has been a concern of ours. However, due to the lack of placebo-controlled trials with ondansetron, interpretation of the study would be hampered as it is currently not known to what degree (if any) ondansetron relieves the symptoms compared with no treatment, especially considering the self-limiting nature of the disease. Hence, showing that mirtazapine is as effective as ondansetron without a placebo group would not prove that mirtazapine is effective. In addition, all participants are allowed to use metoclopramide in case of insufficient symptom relief.

Eligibility criteria

A central matter in this trial is the severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy required to be eligible for participation. Diagnostic criteria for hyperemesis gravidarum lack international consensus and inclusion criteria vary substantially among previously conducted trials on the condition.3 Most frequently reported inclusion criteria include vomiting, nausea, need for hospital treatment, weight loss and ketonuria. However, no studies have disclosed an association between ketonuria and severity of hyperemesis gravidarum, and the use of ketonuria as a diagnostic criteria for hyperemesis gravidarum is thus not recommended.35 36

In this trial, the severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy required for participation is dependent on PUQE-24 score which is a validated questionnaire that grades the severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. The inclusion criterion on severity of the condition is PUQE-24 score ≥13 (severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy) or PUQE-24 score ≥7 (moderate nausea and vomiting in pregnancy) if accompanied by either (1) weight loss >5% of prepregnancy weight or (2) hospitalisation due to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy or hyperemesis gravidarum.

Intervention

It has been a concern whether this patient population would be able to tolerate oral medication and thus both intravenous, rectal, sublingual and orally dissolving administration of trial medication have been considered. However, mirtazapine is only commercially available in a tablet and orally dissolving tablet formulation. While the orally dissolving tablet would be easier to swallow, the strong taste is not well tolerated. We have therefore decided to use oral tablets as trial medication even though we might exclude the most severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum due to the exclusion criterion ‘not able to take trial medication orally’.

The duration of the intervention is 14 days in accordance with previous pharmacological trials on nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum.10 26 A longer lasting intervention would increase the likelihood that a possible decrease in symptoms might be due to the self-limiting nature of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy rather than a consequence of the intervention and would reduce a difference between the placebo group and the two active treatments.

The Danish guideline on hyperemesis gravidarum recommends treatment with ondansetron 8 mg twice daily with optional increase to a maximum total dosage of 32 mg daily.37 The treatment in the ondansetron group thus reflects current practice.

Most of the case reports on mirtazapine and hyperemesis gravidarum describe dosages of up to 15 mg daily to be effective. However, in some case reports the initial dosage was mirtazapine 30 mg daily.16 17 22 Thus, to not disregard a possible effect due to inadequate dosage and better reflect the usage outside a clinical study, this trial allows for an optional dosage increase to 30 mg mirtazapine daily.

Outcomes

Patient-reported outcomes are prioritised over objective measures because this reflects current practice in assessing severity of symptoms in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum where few objective measures are assessed. However, previous trials have had difficulties obtaining complete records for patient-reported outcomes.38 Therefore, we have kept the daily online questionnaires short so answering them will be feasible even for severely affected participants. The more extensive questionnaires are part of the trial visits and thus personnel will ensure collection of these data.

The primary outcomes difference in PUQE-24 score from baseline to day 2 evaluates the short-term effect of the active medications versus placebo. Previous trials in hyperemesis gravidarum have evaluated treatment effect at the end of the intervention; however, they have had issues with missing data due to dropouts during the intervention, especially in the placebo groups.39 The VOMIT trial is conducted without a pilot trial and the first 10 months of recruiting may be viewed as a pilot phase. Like previous trials, we have had a high rate of dropouts due to treatment failure and we have adjusted the primary endpoint accordingly. We have introduced the primary outcome on day 2 as participants are more likely to still be in the trial and treatment effect is expected to be established at this point. Furthermore, this early endpoint diminishes the likelihood of a possible symptom reduction being due to the self-limiting nature of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy rather than a consequence of the intervention. If results are statistically significant on day 2, we will proceed to run analyses on data from day 14.

The outcome treatment failure further enables analyses between the groups in case of dropouts.

Unblinding after end of intervention in case of desire to continue trial medication

Most guidelines recommend ondansetron for severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum and thus, we have discussed whether this should be the treatment offered to participants after the intervention. However, in several case reports, mirtazapine has been effective when ondansetron has not.14 18 22 Thus, in the event that a participant has experienced significant symptom relief during the intervention and therefore wishes to continue the trial medication, we find it unethical not to offer this. This requires unblinding which will happen after the main outcome has been collected and consequently with no influence on the internal validity. This option is supported by patient representatives and has been approved by the statistical consultant.

Ethics and dissemination

Approvals and registrations

The study protocol has been approved by the Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics in the Capital Region of Denmark (H-18047191), the Danish Medicines Agency (EudraCT: 2018-002285-39) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2019-75). The manufacturers of mirtazapine and ondansetron have been notified about the trial, but have not contributed to the protocol, nor have they made financial contributions. The protocol is published on clinicaltrials.gov.

Dissemination

The results of the study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and submitted to relevant conferences. Additionally, trial participants will be informed of the results.

The results of this trial may be integrated in future recommendations on hyperemesis gravidarum.

Trial status

Recruiting started in March 2019 and the trial is currently recruiting at five sites. Recruiting is planned to open at three more sites during early 2020 and last participant included is expected in late 2021 with collection of pregnancy outcome and end of trial in mid 2022.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TSP conceived the trial. AO, TBF, TSP and ECLL developed and designed the trial. AO wrote the first draft of the protocol and all authors were involved in critical revision. The statistical analysis plan was developed by AKJ and AO. AO is the principal investigator and trial coordinator responsible for day-to-day management. ECLL is the guarantor. AO wrote the first draft of this manuscript. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Danish Regions’ Medicinal Grant (grant number EMN-2017-00901), by Nordsjællands Hospital (grant number 18526-e-20225), A & J C Tvergaards Fond, Kong Christian den Tiendes Fond, Kaj og Hermilla Ostenfeld’s Fond, Fru Olga Bryde Nielsens Fond and A. P. Møller Fonden til lægevidenskabens fremme. Further funding is still being pursued.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Jamieson DJ, et al. Hospitalizations during pregnancy among managed care enrollees. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:94–100. 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Einarson TR, Piwko C, Koren G. Quantifying the global rates of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a meta analysis. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2013;20:e171-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koot MH, Boelig RC, Van't Hooft J, et al. Variation in hyperemesis gravidarum definition and outcome reporting in randomised clinical trials: a systematic review. BJOG 2018;125:1514–21. 10.1111/1471-0528.15272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. London V, Grube S, Sherer DM, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum: a review of recent literature. Pharmacology 2017;100:161–71. 10.1159/000477853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, et al. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:285–92. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195060.22832.cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heitmann K, Nordeng H, Havnen GC, et al. The burden of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: severe impacts on quality of life, daily life functioning and willingness to become pregnant again - results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:75 10.1186/s12884-017-1249-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poursharif B, Korst LM, Macgibbon KW, et al. Elective pregnancy termination in a large cohort of women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Contraception 2007;76:451–5. 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boelig RC, Barton SJ, Saccone G, et al. Interventions for treating hyperemesis gravidarum: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:2492–505. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1342805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor LG, Bird ST, Sahin L, et al. Antiemetic use among pregnant women in the United States: the escalating use of ondansetron. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:592–6. 10.1002/pds.4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2013;40:127–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:735–42. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abramowitz A, Miller ES, Wisner KL. Treatment options for hyperemesis gravidarum. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:363–72. 10.1007/s00737-016-0707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benjamin S, Doraiswamy PM. Review of the use of mirtazapine in the treatment of depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011;12:1623–32. 10.1517/14656566.2011.585459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omay O, Einarson A. Is mirtazapine an effective treatment for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy?: a case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2017;37:260–1. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dorn C, Pantlen A, Rohde A. Mirtazapin (Remergil®): Behandlungsoption bei therapieresistenter Hyperemesis gravidarum? - ein Fallbericht. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2002;62:677–80. 10.1055/s-2002-33014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guclu S, Gol M, Dogan E, et al. Mirtazapine use in resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2005;272:298–300. 10.1007/s00404-005-0007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rohde A, Dembinski J, Dorn C, Mirtazapine DC. Mirtazapine (Remergil) for treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: rescue of a twin pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003;268:219–21. 10.1007/s00404-003-0502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saks BR. Mirtazapine: treatment of depression, anxiety, and hyperemesis gravidarum in the pregnant patient. A report of 7 cases. Arch Womens Ment Health 2001;3:165–70. 10.1007/s007370170014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwarzer V, Heep A, Gembruch U, et al. Treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum in a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus: neonatal withdrawal symptoms after successful antiemetic therapy with mirtazapine. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;277:67–9. 10.1007/s00404-007-0406-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uguz F. Low-Dose mirtazapine in treatment of major depression developed following severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: two cases. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014;36:e5–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Uguz F. Low-Dose mirtazapine added to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women with major depression or panic disorder including symptoms of severe nausea, insomnia and decreased appetite: three cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:1066–8. 10.3109/14767058.2013.766697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lieb M, Palm U, Jacoby D, et al. [Mirtazapine and hyperemesis gravidarum]. Nervenarzt 2012;83:374–6. 10.1007/s00115-011-3297-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhattacharjee D, Doleman B, Lund J, et al. Mirtazapine for postoperative nausea and vomiting: systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. J Perianesth Nurs 2019;34:680–90. 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ebrahimi N, Maltepe C, Bournissen FG, et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: using the 24-hour Pregnancy-Unique quantification of emesis (PUQE-24) scale. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31:803–7. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koren G, Clark S, Hankins GDV, et al. Effectiveness of delayed-release doxylamine and pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:e1–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smit M, Dolman KM, Honig A. Mirtazapine in pregnancy and lactation - A systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2016;26:126–35. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winterfeld U, Klinger G, Panchaud A, et al. Pregnancy outcome following maternal exposure to mirtazapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35:250–9. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ingadottir G, Hedegaard L, Poulsen H. Maternal exposure to mirtazapine in the first trimester and the risk of congenital malformations – a nationwide cohort study [abstract], 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Janusinfo Läkemedel och fosterpåverken. Available: https://www.janusinfo.se/beslutsstod/janusmedfosterpaverkan/databas/mirtazapin [Accessed 1 Oct 2019].

- 31. Smit M, Wennink H, Heres M, et al. Mirtazapine in pregnancy and lactation: data from a case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35:163–7. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:878–83. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Straub L, et al. Association of maternal first-trimester ondansetron use with cardiac malformations and oral clefts in offspring. JAMA 2018;320:2429 10.1001/jama.2018.18307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Straub L, et al. Intravenous ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations. JAMA 2019;25:2019–21. 10.1001/jama.2019.18587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niemeijer MN, Grooten IJ, Vos N, et al. Diagnostic markers for hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:e1–15. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dean CR, Shemar M, Ostrowski GAU, et al. Management of severe pregnancy sickness and hyperemesis gravidarum. BMJ 2018;363:k5000 10.1136/bmj.k5000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DSOG Hyperemesis Gravidarum - Guideline - DSOG, 2013. Available: http://gynobsguideline.dk/sandbjerg/Hyperemesisgravidarum.pdf

- 38. Grooten IJ, Koot MH, van der Post JA, et al. Early enteral tube feeding in optimizing treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum: the maternal and offspring outcomes after treatment of hyperemesis by refeeding (mother) randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:ajcn158931–2. 10.3945/ajcn.117.158931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Persaud N, Meaney C, El-Emam K, et al. Doxylamine-Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy randomized placebo controlled trial: Prespecified analyses and reanalysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189978–19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.