Abstract

Objectives

The optimal size of the health workforce for children’s surgical care around the world remains poorly defined. The goal of this study was to characterise the surgical workforce for children across Brazil, and to identify associations between the surgical workforce and measures of childhood health.

Design

This study is an ecological, cross-sectional analysis using data from the Brazil public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde).

Settings and participants

We collected data on the surgical workforce (paediatric surgeons, general surgeons, anaesthesiologists and nursing staff), perioperative mortality rate (POMR) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) across Brazil for 2015.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We performed descriptive analyses, and identified associations between the workforce and U5MR using geospatial analysis (Getis-Ord-Gi analysis, spatial cluster analysis and linear regression models).

Findings

There were 39 926 general surgeons, 856 paediatric surgeons, 13 243 anaesthesiologists and 103 793 nurses across Brazil in 2015. The U5MR ranged from 11 to 26 deaths/1000 live births and the POMR ranged from 0.11–0.17 deaths/100 000 children across the country. The surgical workforce is inequitably distributed across the country, with the wealthier South and Southeast regions having a higher workforce density as well as lower U5MR than the poorer North and Northeast regions. Using linear regression, we found an inverse relationship between the surgical workforce density and U5MR. An U5MR of 15 deaths/1000 births across Brazil is associated with a workforce level of 5 paediatric surgeons, 200 surgeons, 100 anaesthesiologists or 700 nurses/100 000 children.

Conclusions

We found wide disparities in the surgical workforce and childhood mortality across Brazil, with both directly related to socioeconomic status. Areas of increased surgical workforce are associated with lower U5MR. Strategic investment in the surgical workforce may be required to attain optimal health outcomes for children in Brazil, particularly in rural regions.

Keywords: epidemiology, paediatrics, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of geospatial analysis allows precise definition of associations between the surgical workforce and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) across Brazil.

Analysis can demonstrate an inverse relationship between the surgical workforce and U5MR, allowing for location of areas of increased workforce which are associated with lower U5MR levels.

Geospatial tools can confirm disparities in the surgical workforce as well as U5MR across Brazil, and support modelling to define the relationship between the surgical workforce and U5MR.

Our findings of an association between surgical workforce and U5MR does not demonstrate causation, as many confounding factors and modifiers other than surgical disease impact the U5MR

Although our findings of an association between surgical workforce and U5MR does not demonstrate causation.

Introduction

Healthcare is workforce intensive, and an adequate level of human resources is essential to maintain strong health systems. Discrepancies between local health needs and the health workforce leads to clinical errors, wastage of resources and increased patient mortality and morbidity.1 For surgical care, the workforce is grossly inadequate and inequitably distributed in many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), with rural areas disproportionately affected.2 3

Studies from the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery (LCoGS) have proposed a density of 20–40 specialist physicians (surgeons, anaesthesiologists or obstetricians, SAO) per 100 000 general population to attain desired health outcomes, such as perioperative mortality rate (POMR).2–4 However, surgical care for children is fundamentally different from adult care, with surgical resources provided through multiple tiers in a national health system in proportion to population needs and surgical complexity required.5 In these complex health systems, the optimal surgical workforce for children remains poorly defined.

Brazil offers a rich environment to closely examine the health workforce, as it has extremely heterogeneous geography, health infrastructure and socioeconomic status across the country (GINI index 53.3 in 2017).6 7 Brazil has a large public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) and maintains several publicly available datasets (DATASUS).6 8 Efforts to reduce health disparities across the five Brazil regions (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast and South) have made great strides in recent years, particularly through workforce expansion in primary care.9

Previous geospatial analysis by ourselves and others have identified wide disparities in surgical care across Brazil.10 11 Facilities providing surgical care for children are inequitably distributed across the country, with higher density of infrastructure and surgical access per population unit associated with areas of higher socioeconomic status.10 Spatial cluster analysis demonstrated a higher under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) in the poorer North, Northeast and Midwest regions compared to the wealthier Southeast and South regions, although the POMR for a proxy set of children’s conditions does not vary across the country.10 Increased access to surgical care is associated with a lower U5MR, and access to surgical care differs by geographic region independent of socioeconomic status.

The goals of this study are to characterise the surgical workforce for children in the public health system in Brazil using geospatial analysis and to identify associations between the surgical workforce and childhood mortality rates. Through this analysis, we hope to provide an assessment of Brazil’s surgical workforce, identify disparities in workforce distribution and estimate the required surgical workforce to obtain desired health outcomes for children.

Methods

This study is an ecological, cross-sectional, geospatial analysis using data from the Brazil public health system. Brazil is composed of 5570 municipalities across the union of the Federal District and 26 states, which are distributed across five regions (Midwest, North, Northeast, South and Southeast). We collected data on all children <15 years of age undergoing a surgical procedure from 2010 to 2015 across Brazil using datasets from DATASUS (see table 1 for all datasets and study timeframes). Auxiliary data were collected from databases from the World Bank and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistic (IBGE).8 We used several tools of geospatial analysis to explore relationships between surgical workforce, POMR and U5MR. All health estimates were summarised in line with the Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting (GATHER) statement.12

Table 1.

Primary datasets used for analysis derived from the Brazilian public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) which maintains several publicly available datasets (DATASUS)

| Source | Variables | Date range | Data entries | Scope |

| DATASUS: Hospitalisation information system (SIH) |

|

2008–2015 | 267 248 procedures | Appendectomy (ICD 10 0DTJ4ZZ, 0DTJ0ZZ) Laparotomy (ICD 10 0WJP0ZZ) Hernia (ICD 10 0YQ54ZZ, 0YQ64ZZ, 0YQ50ZZ, 0YQ60ZZ, 0WQF4ZZ, 0WUF07Z, 0WUF0KZ, 0BQR4ZZ,0BQS4ZZ, 0BQR0ZZ, 0BQS0ZZ) Colostomy (ICD 10 0WQFXZ2) Abdominal wall reconstruction (ICD 10 0WQF0ZZ) |

| DATASUS: Mortality information system (SIM) |

|

2010–2015 | 326 459 deaths | All deaths between 2010 and 2015 |

| CNES: National registration of health establishments |

|

2014 | 6498 hospitals | District and referral level hospitals |

| World Bank |

|

2010–2013 | 5565 municipalities | – |

| IBGE: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

|

2008–2014 | 5565 municipalities | – |

Auxiliary data collected from the World Bank and IBGE.

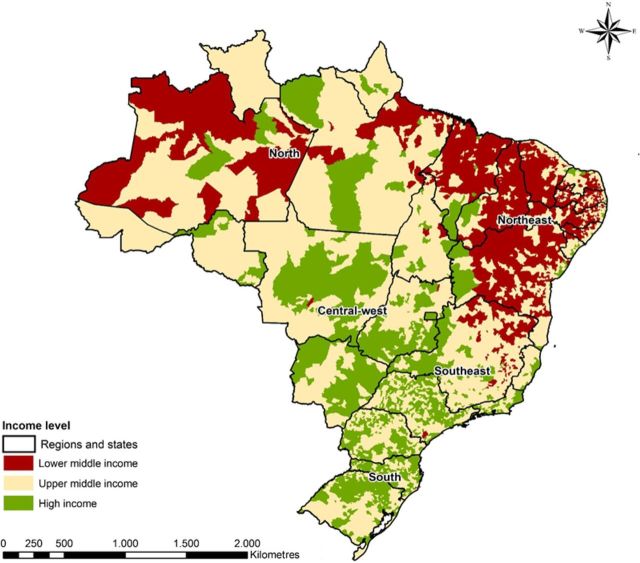

ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

We extracted demographic and socioeconomic indicators from IBGE.13 We used this data along with the Brazilian gross domestic product to classify municipalities according to income groups as high-income, upper-middle income or lower-middle income as defined by the 2017 World Bank criteria of gross national income (GNI) per capita adjusted to US dollars (low income: GNI per capita $1005 or less; lower middle income: GNI per capita between $1006 and $3955; upper middle income: GNI per capita between $3956 and $12 235; high income >$12 235) (figure 1).14

Figure 1.

Income group distribution of Brazilian municipalities. socioeconomic data were extracted from Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistic, and used with the Brazilian gross domestic product to classify municipalities according to income groups as defined by the world bank as high income, upper-middle income or lower-middle income. The map of Brazil was freely obtained in shapefile format through online access to the website of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (https://mapas.ibge.gov.br/bases-e-referenciais/bases-cartograficas/malhas-digitais.html). Reprinted from Vissoci et al.10

Surgical workforce density

We summarised data on the surgical workforce at the municipality, state and regional levels. We summarised several workforce roles, including general surgeons, paediatric surgeons, anaesthesiologists, obstetricians and nurses, using professional role definitions from the CNES. The CNES keeps a record of the appointment of all health providers at public health facilities. The density of each profession was weighted per 100 000 children. For comparison to common surgical workforce metrics used in the LCoGS,2–4 we also summarised the density of SAO.

U5MR and POMR

We summarised annual all-cause U5MR at the regional and municipality level using data from the Brazilian Mortality Information System database (SIM), which collects data on all deaths by age, sex, cause and residence.8 The U5MR was calculated using methods of the Inter Agency Group for Mortality Estimation, and was expressed as deaths per 1000 live births.15

We collected procedure-based POMR from the DATASUS Hospitalization Information System database (SIH) using the procedure codes for a proxy set of general surgical procedures. This set was based on the Optimal Resources for Children’s Surgery document of the Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery which specifies representative surgical procedures to assess the delivery of surgical care within a national health system.5 These five procedures included appendectomy, colostomy, hernia repair, laparotomy and abdominal wall reconstruction for gastroschisis, omphalocele or other indication. The SIH defines perioperative mortality as any death occurring during any surgical procedure. We summarised procedure-specific POMR at the regional level across the country.

Note that due to differences in the data quality,10 we limited analysis of the surgical workforce to use of U5MR as the outcome metric. We chose not to use POMR, as the SIH dataset only records deaths occurring during operative procedures and thus likely far underestimates the true POMR which is generally accepted as within 30 days of surgery.16 We recognise that U5MR measures both surgical and non-surgical causes of child mortality, although we chose to use it for analysis of associations between the surgical workforce and childhood health as it is a widely used measure of health system strength for children.

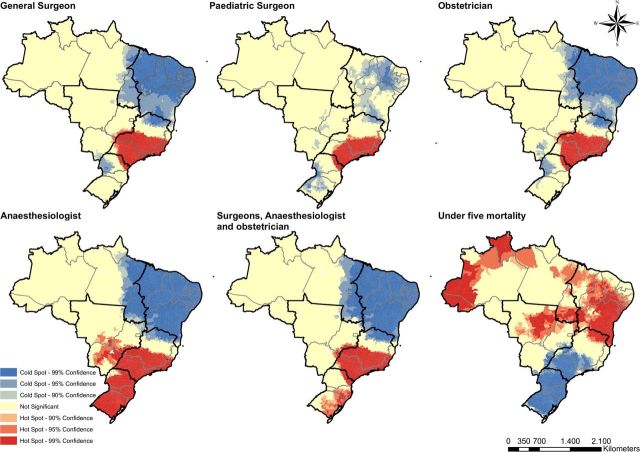

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using the municipality as the main observation unit. We summarised descriptive outcomes at the municipality, state and regional levels. Descriptive statistics were used to report the mean and SD of workforce variables. The density of the surgical workforce and U5MR were displayed using geospatial chloropleth maps. Geographic mapping was used to identify the distribution of each indicator within a spatial area.17 We used a Getis-Ord Gi analysis to depict the spatial autocorrelation within each indicator (workforce density and U5MR). We identified hot spots (red areas) depicting clusters of municipalities with adjacent municipalities with high values for a given indicator (workforce density or U5MR), and cold spots (blue areas) depicting areas of adjacent clusters with low values for each indicator. Yellow areas mark locations where no clustering was observed. Geographic mapping was used to identify the distribution of each indicator within a spatial area.

To identify potential associations between the surgical workforce and U5MR, we used linear regression on the aggregated data on the state level, adjusting for regional distribution. Scatter plots were built to graphically depict the association between workforce and U5MR. Each point in the graphic was proportional to the average U5MR (per 1000 live births), with display by state as well as by region level. We also performed quadratic and splines regression analysis, but the linear models showed better fit to the data, assessed in comparison using analysis of variance and residual evaluation.

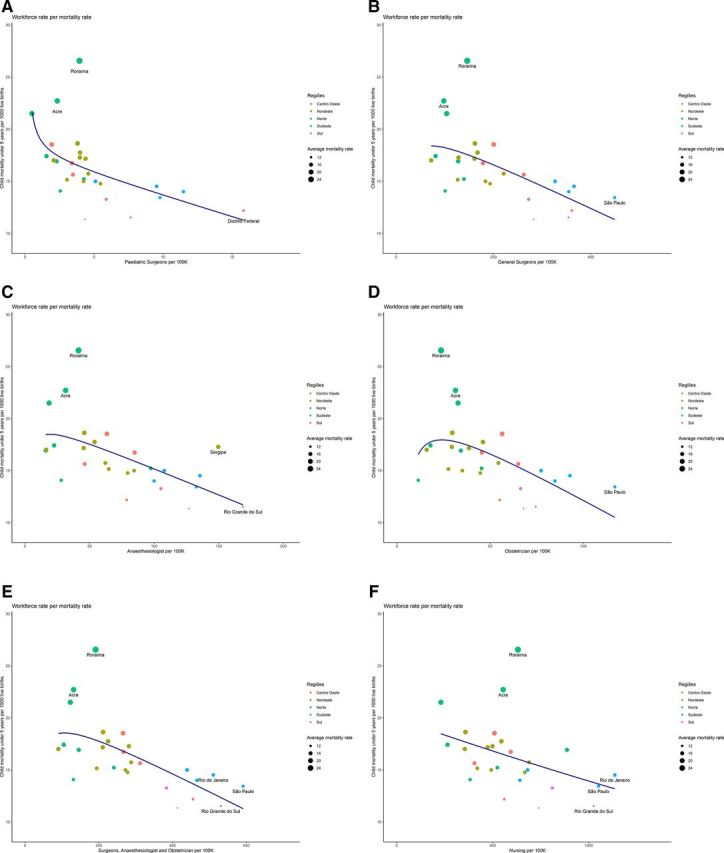

Further analysis evaluated the association between workforce and U5MR accounting for the spatial heterogeneity, using Moran’s I bivariate spatial autocorrelation between each indicator. For our study, we identified high-high spots (red areas) depicting clusters of municipalities with high workforce adjacent municipalities with high values for a U5MR, and low-low spots (blue areas) depicting areas of adjacent clusters with low values for each indicator. High-low (light red areas) and low-high (light blue areas) marked locations cluster of high in one indicator was adjacent to a low in the other.

Patient and public involvement

As an ecological study, there was no direct patient involvement with this research. However, there is public interest in addressing challenges with the surgical care of children in Brazil. We used anonymised publicly available datasets to address these research questions. All research findings will be disseminated to the public and health community in Brazil through publication, academic meetings and social media.

Results

We found that there were 39 926 general surgeons, 856 paediatric surgeons, 13 243 anaesthesiologists, 103 793 nurses and 9674 obstetricians across Brazil in 2015. During the same year, there were 43 045 reported deaths in children under 5 years of age in Brazil, with the U5MR ranging between 11 and 26 deaths/1000 live births across states. The POMR for the proxy set of surgical procedures ranged from 0.11–0.17 deaths/100 000 children across regions.

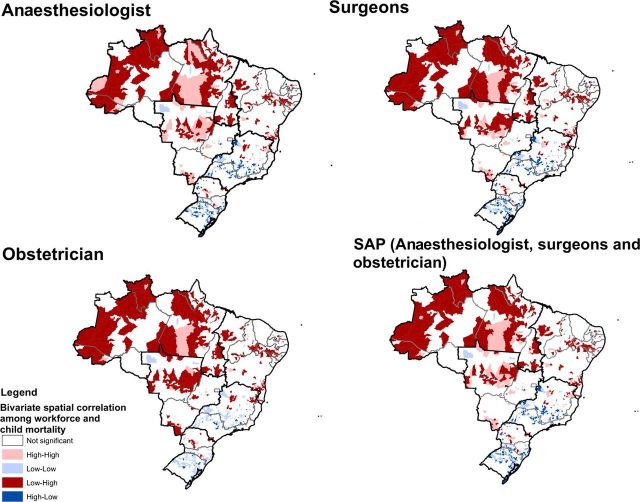

By use of scatter plots, we developed a set of linear regression models to define the association between the density of surgical workforce at the state level and U5MR (figure 2A–F). Using linear regression, we e found all professional roles had a direct relationship between workforce density and U5MR (table 2). However, when adjusting the models by the interaction of workforce density and region of the country, we noticed that some of the associations had lower coefficients and were not significant, suggesting that the association between workforce and U5MR is dependent on the geographic and social context.

Figure 2.

(A–F): Association between the density of the surgical workforce (weighted per 100 000 children) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR, per 1000 live births) in each state across Brazil. Linear regression models were used to define associations between the workforce density and U5MR. The line resulting from each regression model was plotted using bivariate scatter plots. The size of each point in the graphic is proportional to the average U5MR for each state, with different colours used to summarise data by region.

Table 2.

Linear regression coefficients for the association between workforce and under-5 mortality rate in Brazil, unadjusted and adjusted by region of the country

| Mean (SD) | Unadjusted coefficient (SE) | Adjusted coefficient (SE) | |

| General surgeon rate | 208.01 (103.93) | −0.02 (0.01)* | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Paediatric surgeon rate | 4.86 (3.38) | −0.53 (0.17)* | −0.32 (0.20) |

| Obstetrician rate | 48.95 (25.37) | −0.07 (0.02)* | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Anaesthesiologist rate | 74.34 (43.32) | −0.05 (0.01)* | −0.02 (0.02) |

| Surgeons, anaesthesiologists and obstetrician rate | 287.22 (140.70) | −0.02 (0.00)* | −0.01 (0.01) |

*P<0.01.

Disparities in the surgical workforce and U5MR across Brazil

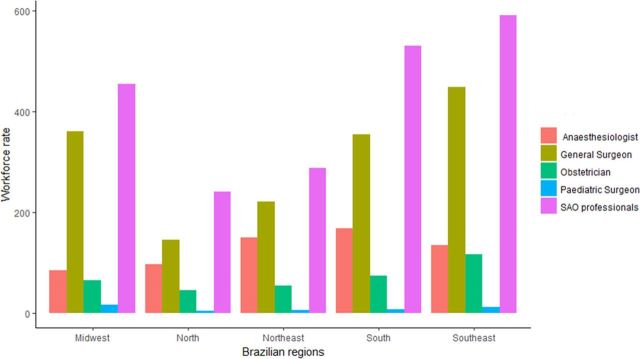

The surgical workforce for children in Brazil is unequally distributed across the country, with the South and Southeast regions having a higher density of all professional roles, while the North and Northeast regions have a lower density of each role (figure 3). We found an inverse pattern of disparities in U5MR across the country,. The South and Southeast regions had the lowest U5MR. In contrast, the North and Northeast regions had higher U5MR (figure 4).

Figure 3.

The density (rate) of the surgical workforce for each professional role across Brazil as summarised by region. The density of each professional role is weighted per 100 000 children. SAO, surgeons, anaesthesiologists or obstetricians.

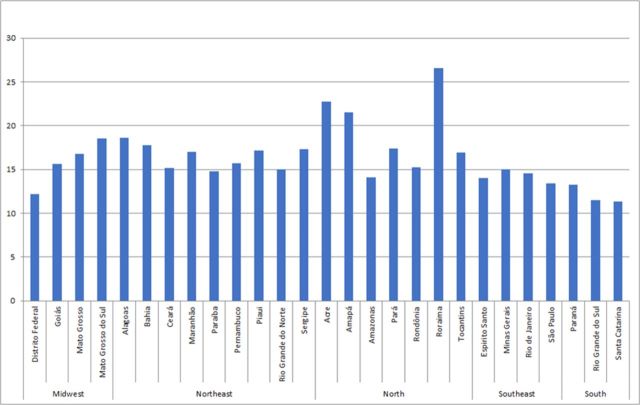

Figure 4.

Under-5 mortality rates (per 1000 live births) across Brazil summarised by state as well as by region levels.

At a municipality level, we found wide disparities in the workforce density as well as U5MR across Brazil, with inequities even within states (figure 5). Several municipalities did not have even one general surgeon, paediatric surgeon, obstetrician or anaesthesiologist. Some wealthier parts of the North and Northeast regions showed high inequities in workforce distribution, with the workforce preferentially localised in areas around the state capitals. The high areas of workforce distribution was similar to the patterns of low U5MR seen at the municipality level.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the surgical workforce density (weighted per 100 000 children) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR, per 1000 live births) at the municipality level. hot spot cluster analysis of association between the surgical workforce density (weighted per 100 000 children) and U5MR (per 1000 live births) across Brazil using Getis-Ord-Gi analysis.17 hot spots (red areas) depict clusters of municipalities with adjacent municipalities with high values for a given indicator (workforce density or U5MR), and cold spots (blue areas) depict clusters with an adjacent low values regarding each indicator. Yellow areas mark locations where no clustering was observed. Note that the scatter plots are not adjusted for spatial autocorrelation.

Relationship between surgical workforce density and U5MR

We found a direct association between the surgical workforce and U5MR across Brazil, with higher density of each professional role associated with lower U5MR across regions (figure 6, table 2). This pattern is consistent across workforce roles (surgeon, anaesthesiologist, nursing, etc), although there are some variations in the distribution patterns across the country. For example, in the South and Southeast, we found the highest density of paediatric surgeons as well as the lowest levels of U5MR, although this pattern was not seen in the Federal District, where there was a high density of all workforce roles as well as higher levels of U5MR compared to surrounding regions. The Federal district is where the Brazilian government is located, and the density of the surgical workforce in this state-city was higher than in all other states.

Figure 6.

Association between the surgical workforce density (weighted per 100 000 children) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR, per 1000 live births) across Brazil using spatial correlation analysis. High-high areas (red areas) depict clusters of municipalities with high values for workforce adjacent municipalities with high values for a U5MR, and low-low areas (blue areas) depict clusters with an adjacent low values regarding each indicator.

Discussion

As surgical care is an essential component of functioning healthcare systems, there is a need to improve our understanding of the surgical workforce for children. Brazil has wide disparities in socioeconomic status and healthcare delivery.18 19 Our previous work has shown disparities in the density of delivery and infrastructure for surgical care for children per population unit across Brazil, with areas of higher socioeconomic status associated with increased delivery of surgical care.10 Although Brazil does have widely variable geography, these disparities are corrected for population density, and therefore reflect underlying disparities in health access. Our current study demonstrates disparities in the surgical workforce across the country, with a higher workforce density per population unit found in areas of higher socioeconomic status. In addition, increased surgical workforce density is associated with areas of lower U5MR, suggesting that an adequate and equitable surgical workforce is essential for support of high-quality healthcare for children.

Disparities in surgical care for adults have been previously noted in Brazil as well as other countries, although disparities in the surgical care for children remain poorly understood. Reports from the LCoGS have shown an association between the density of SAO and the rate of surgical procedures or POMRs.2–4 Our data align with recent analyses of surgical care for adults in Brazil which showed wide disparities in manpower and surgical care.11 20 The Brazilian government has long recognised challenges with healthcare delivery across the country, and have implemented several programs to increase primary care access in rural areas.6 9 21

The POMR is often used to gauge the quality of a surgical system,16 although we suggest that metrics of overall childhood health such as U5MR may offer an alternative, and potentially even more valuable metric to guide manpower planning. First, given the increasing emphasis on surgical care as an integral part of a comprehensive health system, associations between each aspect of the health workforce and overall measures of population health may be the most appropriate measure of manpower across an entire health system, including the surgical workforce.16 For example, neonates or children with cancer often require surgical care, and an adequate surgical workforce is essential to ensure high-quality outcomes for these children. Second, despite interest around the world for collection of POMRs, data quality for POMR continues to be challenging in many settings.22 Our previous work in Brazil suggests that data quality for POMR is too poor to allow for analysis of the surgical workforce.10 16 Third, the United Nations and the WHO have identified several indicators to evaluate health interventions in children, including the U5MR, rate of growth stunting, immunisation coverage and prevalence of common childhood diseases.23 These metrics are routinely collected around the world, and our analysis suggests that strategic expansion of the surgical workforce can be guided by these widely collected metrics. Finally, we confirmed an association between the nursing workforce and U5MR, as few analyses have examined the nursing workforce requirements for surgical care.

To assist with policy development, geospatial analysis can identify priority regions of workforce needs. The sequence of steps in our analysis may be generalisable to other countries to guide scale-up of the surgical workforce to desired levels of health outcomes. For example, we found that U5MR of 15 deaths/1000 births across Brazil is associated with an approximate workforce level of 5 paediatric surgeons, 200 surgeons, 100 anaesthesiologists or 700 nurses/100 000 children. Geospatial analyses has help guide health workforce expansion in Thailand,24 as well as in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa.25 However, we caution that the workforce associations in Brazil may not be applicable to other countries. In addition, geospatial analysis requires access to high-quality national datasets which remains problematic in many countries around the world.

The areas of Brazil with lower socioeconomic status remain challenging environments for healthcare, where there is a long history of difficulties with retention of healthcare professionals.18 19 Our findings align with studies of adult surgical workforce in Brazil which have shown inequities in the density of SAO professionals across the country, with rural regions disproportionately affected.26 Similar to many counties around the world, the rural areas in Brazil have high levels of poverty and a scarcity of health infrastructure.27 28 Brazil has successfully increased access to the primary care workforce in rural areas through the Mais Médicos programme,29 and our findings suggest that similar expansion of the surgical workforce may improve the health of children.

As with any population-based study, our work has several limitations. First, our findings of an association between surgical workforce and U5MR do not demonstrate causation. We recognise that many confounders other than surgical workforce impacts the U5MR (such as non-surgical disease, non-surgical workforce, etc). However, we view surgical care as a core component of a functional health system, and therefore association between the surgical workforce and U5MR can help guide workforce planning. Although our analysis did not account for detailed study of the confounding and modifying variables which impact the U5MR, further discernment of which components of a health workforce are most important for childhood health is a critical question that merits further analysis. Second, there is a lack of consensus in geospatial analysis about how the density of professionals should be weighted regarding different populations (ie, overall population, child population, etc), although we chose to weigh by child population. Finally, we recognise that the surgical workforce includes many type of subspecialists that were not included in our analysis.

In conclusion, we found that the surgical workforce for children is inadequate and inequitably distributed across Brazil, suggesting that strategic investment in the surgical workforce is required to support high-quality and equitable healthcare for children. There is a direct relation between the surgical workforce and U5MR across Brazil, with higher levels of the surgical workforce associated with improved U5MR. These findings have several policy implications to improve the health of children in Brazil:

Increased investment in the surgical workforce is required to support the health of children in Brazil, particularly in rural regions

Identification of associations between the workforce and measures of population health (such as U5MR) may be a valuable tool to define surgical workforce levels in LMICs.

Definition of workforce indicators is particularly challenging for children’s surgical care given the complexity of care across different levels of national health systems.

Geospatial analysis can help define the required surgical workforce to attain desired population health goals, and may be generalisable across other LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the Global Initiative for Children's Surgery (GICS) for its support of this work. GICS (www.globalchildrenssurgery.org) is a network of children's surgical and anaesthesia providers from low-income, middle-income and high-income countries collaborating for the purpose of improving the quality of surgical care for children globally. There was no external funding source for this study.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery: Francis A. Abantanga, Mohamed Abdelmalak, Nurudeen Abdulraheem, Niyi Ade-Ajayi, Edna Adan Ismail, Adesoji Ademuyiwa, Eltayeb Ahmed, Sunday Ajike, Olugbemi Benedict Akintububo, Felix Alakaloko, Brendan Allen, Vanda Amado, Emmanuel Ameh, Shanthi Anbuselvan, Jamie Anderson, Theophilus Teddy Kojo Anyomih, Leopold Asakpa, Gudeta Assegie, Jason Axt, Ruben Ayala, Frehun Ayele, Harshjeet Singh Bal, Rouma Bankole, Tahmina Banu, Tim Beacon, Stephen Bickler, Zaitun Bokhari, Hiranya Kumar Borah, Eric Borgstein, Nick Boyd, Jason Brill, Britta Budde-Schwartzman, Fred Bulamba, Marilyn Butler, Bruce Bvulani, Sarah Cairo, Juan Francisco Campos Rodezno, Massimo Caputo, Milind Chitnis, Maija Cheung, Bruno Cigliano, Damian Clarke, Tessa Concepcion, Michael Cooper, Scott Corlew, David Cunningham, Sergio D’Agostino, Shukri Dahir, Bailey Deal, Miliard Derbew, Sushil Dhungel, David Drake, Elizabeth Drum, Bassey Edem, Stella Eguma, Olumide Elebute, Beda R. Espineda, Samuel Espinoza, Faye Evans, Omolara Faboya, Jacques Fadhili Bake, Diana Farmer, Tatiana Fazecas, Mohammad Rafi Fazli, Graham Fieggen, Anthony Figaji, Jean Louis Fils, Tamara Fitzgerald, Randall Flick, Gacelle Fossi, George Galiwango, Mike Ganey, Zipporah Gathuya, Maryam Ghavami Adel, Vafa Ghorban Sabagh, Sridhar Gibikote, Hetal Gohil, Laura Goodman, David Grabski, Sarah Greenberg, Russell Gruen, Lars Hagander, Rahimullah Hamid, Erik Hansen, William Harkness, Mauricio Herrera, Intisar Hisham, Andrew Hodges, Sarah Hodges, Ai-Xuan Holterman, Andrew Howard, Romeo Ignacio, Dawn Ireland, Enas Ismail, Rebecca Jacob, Anette Jacobsen, Zahra Jaffry, Deeptiman James, Ebor Jacob James, Adiyasuren Jamiyanjav, Kathy Jenkins, Guy Jensen, Maria Jimenez, Tarun John K Jacob, Walter Johnson, Anita Joselyn, Nasser Kakembo, Patrick Kamalo, Neema Kaseje, Bertille Ki, Phyllis Kisa, Peter Kim, Krishna Kumar, Rashmi Kumar, Charlotte Kvasnovsky, Kokila Lakhoo, Ananda Lamahewage, Monica Langer, Christopher Lavy, Taiwo Lawal, Colin Lazarus, Andrew Leather, Chelsea Lee, Basil Leodoro, Allison Linden, Katrine Lofberg, Jonathan Lord, Jerome Loveland, Leecarlo Millano Lumban Gaol, Vrisha Madhuri, Pavrette Magdala, Luc Kalisya Malemo, Aeesha Malik, John Mathai, Marcia Matias, Bothwell Mbuwayesango, Merrill McHoney, Liz McLeod, Ashish Minocha, Charles Mock, Mubarak Mohamed, Ivan Molina, Ashika Morar, Zahid Mukhtar, Mulewa Mulenga, Bhargava Mullapudi, Jack Mulu, Byambajav Munkhjargal, Arlene Muzira, Mary Nabukenya, Mark Newton, Jessica Ng, Karissa Nguyen, Laurence Isaaya Ntawunga, Peter M. Nthumba, Alp Numanoglu, Benedict Nwomeh, Kristin Ojomo, Keith Oldham, Maryrose Osazuwa, Doruk Ozgediz, Emmanuel Owusu Abem, Shazia Peer, Norgrove Penny, Robin Petroze, Dan Poenaru, Vithya Priya, Ekta Rai, Lola Raji, Vinitha Paul Ravindran, Desigen Reddy, Henry Rice, Yona Ringo, Amezene Robelie, Jose Roberto Baratella, David Rothstein, Coleen Sabatini, Soumitra Saha, Lily Saldaña Gallo, Saurabh Saluja, Lubna Samad, John Sekabira, Justina Seyi-Olajide, Bello B. Shehu, Ritesh Shrestha, Sabina Siddiqui, David Sigalet, Martin Situma, Emily Smith, Adrienne Socci, David Spiegel, Peter Ssenyonga, Etienne St-Louis, Jacob Stephenson, Erin Stieber, Richard Stewart, Vinayak Shukla, Thomas Sims, Faustin Felicien Mouafo Tambo, Robert Tamburro, Mansi Tara, Ahmad Tariq, Reju Thomas, Leopold Torres Contreras, Stephen Ttendo, Benno Ure, Luca Vricella, Luis Vasquez, Vijayakumar Raju, Jorge Villacis, Gustavo Villanova, Catherine deVries, Amira Waheeb, Saber Waheeb, Albert Wandaogo, Anne Wesonga, Omolara Williams, Sigal Willner, Nyo Nyo Win, Hussein Wissanji, Paul Mwindekuma Wondoh, Garreth Wood, Naomi Wright, Benjamin Yapo, George Youngson, Yasmine Yousef, Denle'wende' Sylvain Zabsonre, Luis Enrique, Zea Salazar, Adiyasuren Zevee, Bistra Zheleva.

Contributors: TAHR, JV and HER had the initial idea for this analysis. TAHR, JV, NCS and HER performed the initial analysis and wrote the first draft. The analysis and manuscript were completed and revised in collaboration with DP, MGS and ERS. All co-authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data used for this analysis were obtained from the open access DATASUS system, from the Brazilian Ministry of Health. Data can be obtained, freely, from: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/.

Contributor Information

Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery:

Mohamed Abdelmalak, Nurudeen Abdulraheem, Niyi Ade-Ajayi, Edna Adan Ismail, Adesoji Ademuyiwa, Eltayeb Ahmed, Sunday Ajike, Olugbemi Benedict Akintububo, Felix Alakaloko, Brendan Allen, Vanda Amado, Emmanuel Ameh, Shanthi Anbuselvan, Jamie Anderson, Theophilus Teddy Kojo Anyomih, Leopold Asakpa, Gudeta Assegie, Jason Axt, Ruben Ayala, Frehun Ayele, Harshjeet Singh Bal, Rouma Bankole, Tahmina Banu, Tim Beacon, Stephen Bickler, Zaitun Bokhari, Hiranya Kumar Borah, Eric Borgstein, Nick Boyd, Jason Brill, Britta Budde-Schwartzman, Fred Bulamba, Marilyn Butler, Bruce Bvulani, Sarah Cairo, Juan Francisco Campos Rodezno, Massimo Caputo, Milind Chitnis, Maija Cheung, Bruno Cigliano, Damian Clarke, Tessa Concepcion, Michael Cooper, Scott Corlew, David Cunningham, Sergio D’Agostino, Shukri Dahir, Bailey Deal, Miliard Derbew, Sushil Dhungel, David Drake, Elizabeth Drum, Bassey Edem, Stella Eguma, Olumide Elebute, Beda R. Espineda, Samuel Espinoza, Faye Evans, Omolara Faboya, Jacques Fadhili Bake, Diana Farmer, Tatiana Fazecas, Mohammad Rafi Fazli, Graham Fieggen, Anthony Figaji, Jean Louis Fils, Tamara Fitzgerald, Randall Flick, Gacelle Fossi, George Galiwango, Mike Ganey, Zipporah Gathuya, Maryam Ghavami Adel, Vafa Ghorban Sabagh, Sridhar Gibikote, Hetal Gohil, Laura Goodman, David Grabski, Sarah Greenberg, Russell Gruen, Lars Hagander, Rahimullah Hamid, Erik Hansen, William Harkness, Mauricio Herrera, Intisar Hisham, Andrew Hodges, Sarah Hodges, Ai-Xuan Holterman, Andrew Howard, Romeo Ignacio, Dawn Ireland, Enas Ismail, Rebecca Jacob, Anette Jacobsen, Zahra Jaffry, Deeptiman James, Ebor Jacob James, Adiyasuren Jamiyanjav, Kathy Jenkins, Guy Jensen, Maria Jimenez, Tarun John K Jacob, Walter Johnson, Anita Joselyn, Nasser Kakembo, Patrick Kamalo, Neema Kaseje, Bertille Ki, Phyllis Kisa, Peter Kim, Krishna Kumar, Rashmi Kumar, Charlotte Kvasnovsky, Kokila Lakhoo, Ananda Lamahewage, Monica Langer, Christopher Lavy, Taiwo Lawal, Colin Lazarus, Andrew Leather, Chelsea Lee, Basil Leodoro, Allison Linden, Katrine Lofberg, Jonathan Lord, Jerome Loveland, Leecarlo Millano Lumban Gaol, Vrisha Madhuri, Pavrette Magdala, Luc Kalisya Malemo, Aeesha Malik, John Mathai, Marcia Matias, Bothwell Mbuwayesango, Merrill McHoney, Liz McLeod, Ashish Minocha, Charles Mock, Mubarak Mohamed, Ivan Molina, Ashika Morar, Zahid Mukhtar, Mulewa Mulenga, Bhargava Mullapudi, Jack Mulu, Byambajav Munkhjargal, Arlene Muzira, Mary Nabukenya, Mark Newton, Jessica Ng, Karissa Nguyen, Laurence Isaaya Ntawunga, Peter M. Nthumba, Alp Numanoglu, Benedict Nwomeh, Kristin Ojomo, Keith Oldham, Maryrose Osazuwa, Doruk Ozgediz, Emmanuel Owusu Abem, Shazia Peer, Norgrove Penny, Robin Petroze, Dan Poenaru, Vithya Priya, Ekta Rai, Lola Raji, Vinitha Paul Ravindran, Desigen Reddy, Henry Rice, Yona Ringo, Amezene Robelie, Jose Roberto Baratella, David Rothstein, Coleen Sabatini, Soumitra Saha, Lily Saldaña Gallo, Saurabh Saluja, Lubna Samad, John Sekabira, Justina Seyi-Olajide, Bello B. Shehu, Ritesh Shrestha, Sabina Siddiqui, David Sigalet, Martin Situma, Emily Smith, Adrienne Socci, David Spiegel, Peter Ssenyonga, Etienne St-Louis, Jacob Stephenson, Erin Stieber, Richard Stewart, Vinayak Shukla, Thomas Sims, Faustin Felicien Mouafo Tambo, Robert Tamburro, Mansi Tara, Ahmad Tariq, Reju Thomas, Leopold Torres Contreras, Stephen Ttendo, Benno Ure, Luca Vricella, Luis Vasquez, Vijayakumar Raju, Jorge Villacis, Gustavo Villanova, Catherine deVries, Amira Waheeb, Saber Waheeb, Albert Wandaogo, Anne Wesonga, Omolara Williams, Sigal Willner, Nyo Nyo Win, Hussein Wissanji, Paul Mwindekuma Wondoh, Garreth Wood, Naomi Wright, Benjamin Yapo, George Youngson, Yasmine Yousef, Denle'wende' Sylvain Zabsonre, Luis Enrique, Zea Salazar, Adiyasuren Zevee, and Bistra Zheleva

References

- 1. Lopes MA, Almeida Álvaro Santos, Almada-Lobo B. Handling healthcare workforce planning with care: where do we stand? Hum Resour Health 2015;13:38 10.1186/s12960-015-0028-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386:569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmer H, Lantz A, Kunjumen T, et al. Global distribution of surgeons, anaesthesiologists, and obstetricians. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3 Suppl 2:S9–11. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70349-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P, et al. Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the who global health estimate. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3 Suppl 2:S13–20. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70087-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goodman LF, St-Louis E, Yousef Y, et al. The global initiative for children's surgery: optimal resources for improving care. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2018;28:051–9. 10.1055/s-0037-1604399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, et al. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet 2011;377:1778–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bank W. GINI index (world bank estimate) Washington DC: world bank, 2017. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/si.pov.gini

- 8. Brasil Departamento de Informática do SUS - DATASUS. Informações de Saúde (TABNET) 2015. Available: http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=02 [Accessed June 2015].

- 9. Nunes BP, Thumé E, Tomasi E, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in the access to and quality of health care services. Rev Saude Publica 2014;48:968–76. 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vissoci JRN, Ong CT, Andrade Lde, et al. Disparities in surgical care for children across Brazil: use of geospatial analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0220959 10.1371/journal.pone.0220959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Massenburg BB, Saluja S, Jenny HE, et al. Assessing the Brazilian surgical system with six surgical indicators: a descriptive and modelling study. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000226 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the gather statement. Lancet 2016;388:e19–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Estatísticas sociodemograficas do Brasil 2014. Available: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/ [Accessed Jan 2018].

- 14. World Health Organization World health statistics 2017: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. UNICEF, WHO, Bank TW . Levels and trends of child mortality in 2006: estimates developed by the Inter-agency group for child mortality estimation new York2007. Available: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Attach/Capacity/Ind%204-1.pdf [Accessed 1 Sep 2018].

- 16. Watters DA, Hollands MJ, Gruen RL, et al. Perioperative mortality rate (POMR): a global indicator of access to safe surgery and anaesthesia. World J Surg 2015;39:856–64. 10.1007/s00268-014-2638-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Getis A, Ord JK. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr Anal 1992;24:189–206. 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1992.tb00261.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rocha TAH, da Silva NC, Amaral PV, et al. Access to emergency care services: a transversal ecological study about Brazilian emergency health care network. Public Health 2017;153:9–15. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santos ASD, Duro SMS, Cade NV, et al. Quality of infant care in primary health services in southern and northeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2018;52:11. 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alonso N, Massenburg BB, Galli R, et al. Surgery in Brazilian health care: funding and physician distribution. Rev Col Bras Cir 2017;44:202–7. 10.1590/0100-69912017002016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brazil. Programa Mais Medicos , 2015. Available: http://maismedicos.gov.br/ [Accessed 1 Feb 2015].

- 22. Ng-Kamstra JS, Arya S, Greenberg SLM, et al. Perioperative mortality rates in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000810 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization Monitoring maternal, newborn and child health: understanding key progress indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Witthayapipopsakul W, Cetthakrikul N, Suphanchaimat R, et al. Equity of health workforce distribution in Thailand: an implication of concentration index. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2019;12:13–22. 10.2147/RMHP.S181174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agyepong IA, Sewankambo N, Binagwaho A, et al. The path to longer and healthier lives for all Africans by 2030: the Lancet Commission on the future of health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2018;390:2803–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31509-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scheffer MC, Guilloux AGA, Matijasevich A, et al. The state of the surgical workforce in Brazil. Surgery 2017;161:556–61. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bearden A, Fuller AT, Butler EK, et al. Rural and urban differences in treatment status among children with surgical conditions in Uganda. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205132 10.1371/journal.pone.0205132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith ER, Vissoci JRN, Rocha TAH, et al. Geospatial analysis of unmet pediatric surgical need in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1691–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lima RTdeS, Fernandes TG, Balieiro AAdaS, et al. Primary health care in Brazil and the MAIS Médicos (more doctors) program: an analysis of production indicators. Cien Saude Colet 2016;21:2685–96. 10.1590/1413-81232015219.15412016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.