Abstract

This manuscript is devoted to the nonlinear dynamics of particulate assemblages in metastable liquids, caused by various dynamical laws of crystal growth and nucleation kinetics. First of all, we compare the quasi-steady-state and unsteady-state growth rates of spherical crystals in supercooled and supersaturated liquids. It is demonstrated that the unsteady-state rates transform to the steady-state ones in a limiting case of fine particles. We show that the real crystals evolve slowly in a more actual case of unsteady-state growth laws. Various growth rates of particles are tested against experimental data in metastable liquids. It is demonstrated that the unsteady-state rates describe the nonlinear behaviour of experimental curves with increasing the growth time or supersaturation. Taking this into account, the crystal-size distribution function and metastability degree are analytically found and compared with experimental data on crystallization in inorganic and organic solutions. It is significant that the distribution function is shifted to smaller sizes of particles if we are dealing with the unsteady-state growth rates. In addition, a complete analytical solution constructed in a parametric form is simplified in the case of small fluctuations in particle growth rates. In this case, a desupercooling/desupersaturation law is derived in an explicit form. Special attention is devoted to the biomedical applications for insulin and protein crystallization.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Patterns in soft and biological matters’.

Keywords: nucleation, evolution of particulate assemblage, metastable liquid, phase transformation, distribution function, desupercooling/desupersaturation

1. Introduction

The mechanisms of nucleation and crystal growth in metastable liquids (supercooled melts or supersaturated solutions) completely determine the dynamics of a polydisperse ensemble of particles and aggregates, as well as the evolution of the metastability degree (supercooling or supersaturation) [1–10]. As this takes place, crystal growth rates differ during various stages of the phase transformation processes. So, for example, crystals intensively and independently evolve at the intermediate stage when the system metastability changes from its initial value to a certain small value [11,12]. At the concluding stage, the growth of each particle influences the evolution of neighbouring crystals so that Ostwald ripening, coagulation and fragmentation processes are capable of occurring [13–17]. Let us especially note that such processes as external electromagnetic fields [18], buoyancy forces [19], polymerization [9,20] and withdrawal mechanisms of product crystals from a crystallizer [21–24] may essentially change the dynamics of particulate assemblages in a metastable liquid as well.

This article is concerned with the growth rates of spherical crystals at the intermediate stage of phase transformations in supercooled melts and supersaturated solutions. In these systems, the steady-state laws (2.9) of crystal growth are often used, resulting from the solution of the steady-state thermal conductivity and/or diffusion equations (see, for details, §2). Another approach is to apply purely empirical laws of growth, when the rate of evolution of the interphase boundary of a spherical crystal is proportional to the arbitrary power of supercooling/supersaturation [12,25,26]. Moreover, this power should be found experimentally for each specific process of crystal growth in a metastable liquid. Note that both of these approaches are not strict and do not give an answer about the transient behaviour of nuclei. Such behaviour, in particular, is important when considering particle fluctuations during initial stages of desupercooling/desupersaturation in a metastable liquid. Below we discuss the behaviour of unsteady-state growth rates, compare them with experimental data as well as with the approximate quasi-steady-state growth theory. A complete analytical solution for the evolution of a dispersed particulate assemblage is also constructed and compared with various experiments.

2. Quasi-steady-state growth of spherical crystals

Let us first pay attention to the steady-state growth laws of spherical crystals in single-component and binary systems induced by the corresponding supercooling or supersaturation. We will also assume that the growth of each crystal occurs independently of the growth of other particles and that during its growth the crystal does not change the temperature and/or solute concentration far from it. What is more, we assume in this section that the temperature and/or solute concentration field around the growing crystal is described by the steady-state thermal conductivity and/or diffusion equations. This approximation means that temperature and/or solute concentration changes with time are completely determined by the evolution of the solid/liquid interface. Let us especially emphasize that this hypothesis, traditionally used for the simplicity of solving the Stefan-type problem with an unknown moving boundary, is generally incorrect (see, for more details, §3). For the convenience of presenting the theory, we consider separately the models of steady-state growth in one-component and binary supercooled melts, and supersaturated solutions.

(a). Evolution of spherical crystals in one-component melts

Growth of a spherical crystal of radius R in a supercooled single-component liquid releases the latent heat LV of phase transition on its surface R(t), which evolves with time t. This process changes the thermal field T in the liquid phase around the growing crystal (at r > R(t), where r is the spherical coordinate), which is conveniently described in a spherical coordinate system using the steady-state thermal conductivity equation. It should be especially highlighted that the stationarity of the thermal field means that the latent heat of crystallization released at the phase interface r = R(t) is completely removed to the colder liquid surrounding the growing crystal. By this is meant that the thermal flux λl∂T/∂r as well as the temperature difference at r = R(t) determine the crystal growth rate V(t) = dR/dt. Here λl and designate the thermal conductivity coefficient in liquid and the phase transition temperature of a single-component melt. The temperature field Tl far from the growing crystal (at r ≫ R(t)) is assumed known. All of the above is described using the following simplified problem:

| 2.1 |

Here stands for the kinetic coefficient.

The solution to the problem (2.1) determines the temperature distribution around the spherical crystal and its growth rate as

| 2.2 |

where ΔT is the melt supercooling, and qT = LV/λl. Note that the growth rate (2.2) derived from the steady-state thermal conductivity equation increases with increasing supercooling ΔT and decreases with increasing crystal radius R(t).

(b). Evolution of spherical crystals in binary melts

Let us now consider the case of crystal growth in a binary melt with allowance for the steady-state approximations for the temperature and solute concentration fields. In this case, the phase transition temperature Tp depends on the solute concentration C in accordance with the corresponding phase diagram. For the sake of simplicity, we use here the liquidus line equation representing a linear combination between Tp and C of the form , where and m stand for the phase transition temperature for a one-component melt (with C = 0) and the slope of liquidus line. In addition to the heat flux, the motion of the phase transition boundary r = R(t) is determined by impurity fluxes (displaced into the liquid phase and absorbed by the solid phase). Moreover, the far-field temperature Tl and solute concentration Cl are regarded as known. The aforementioned problem is described by the following phase transition problem

| 2.3 |

where k0 and Dl represent the equilibrium partition coefficient and the diffusion coefficient.

The solution to the problem (2.3) defines the crystal growth rate at r = R(t), where satisfies the quadratic equation

| 2.4 |

Our estimates for metallic alloys show that typically A ≪ 1 for (see also [27–34]). If this is really the case, we have from (2.4) the linear dependence for . Let us especially underline that ΔT represents the melt supercooling for a binary system. It means that now ΔT differs from supercooling determined in the previous subsection. Keeping this in mind, we get from (2.4) the growth rate of crystals in a binary melt

| 2.5 |

Note that the growth rates (2.2) and (2.5) found for one-component and binary melts formally coincide for Cl = 0.

(c). Evolution of spherical crystals in solutions

We now turn to the problem of growth of a spherical crystal in a supersaturated solution. As before, we use in this subsection the steady-state approximation for the solute concentration field. The solute concentration flux Dl∂C/∂r as well as the concentration difference C − Cp at r = R(t) determine the crystal growth rate V(t) = dR/dt. Here Cp designates the concentration at saturation. In addition, the solute concentration Cl far from the crystal is regarded as known. Taking all this into account, we come to the following problem:

| 2.6 |

The first equation (2.6) can be easily integrated. Substituting the result of integration into the boundary conditions at r = R(t) and r ≫ R(t), one can obtain the equation for V = dR/dt. As the crystal growth rate V in the steady-state approximation is considered to be slow, one can neglect the quadratic term (the term proportional to V2) and arrive at the following expressions for the solute impurity around the evolving crystal and its growth rate:

| 2.7 |

where ΔC represents the system supersaturation, and qC = Cp(k0 − 1)/Dl. As is easily seen from (2.7), the growth rate V(t) decreases with decreasing the liquid supersaturation ΔC and increasing the crystal radius R(t).

(d). Some generalizing features

An important point of crystal growth in metastable liquids [one-component and binary supercooled melts (sm) or supersaturated solutions (ss)] is a similar form of all growth rates (2.2), (2.5) and (2.7) in these systems. So, introducing the following designations:

| 2.8 |

one can rewrite the growth rates (2.2), (2.5) and (2.7) in a generalized form

| 2.9 |

Note that expression (2.9) describes the growth rate of spherical crystals in metastable liquids with allowance for the steady-state approximations of the thermal conductivity and/or diffusion equations.

The next important conclusion follows from (2.9) in the case of so-called kinetic mode characterizing the growth of fine crystals when . In this limiting case, the growth rate depends only on the metastability degree Δ (supercooling or supersaturation). In the opposite case of diffusionally controlled mode (when the growth of crystals is completely characterized by the rate of heat or mass removal), the growth rate is directly proportional to the metastability degree Δ and inversely proportional to the current value of crystal radius R(t). Taking this into account, we get from (2.9) the following approximate expressions:

| 2.10 |

It is significant that the growth rate (2.9) can be integrated to express the evolutionary dependence for the crystal radius R(t). If we are dealing with a more general case when the metastability degree Δ in liquid changes with time t due to the evolution of particulate ensembles, we have

| 2.11 |

where , is the critical radius of nucleating particle, and ν is the time moment of its nucleation.

3. Unsteady-state growth of spherical crystals

Generally speaking, the temperature and/or solute concentration field in the liquid phase around the growing spherical crystal is not steady-state. This means that for a more accurate description of the crystal growth process it is necessary to solve the partial differential equations for thermal and/or mass transport in the liquid phase that surrounds the particle. From a mathematical point of view, such a solution will lead to a different growth law (different from the aforementioned formulae (2.2), (2.5), (2.7) or (2.9)). From a physical point of view, this will change the dependencies (2.2), (2.5), (2.7) of the crystal growth rate on supercooling/supersaturation, particle radius and time. So, for example, there is a large number of experimental data [11,35–38] demonstrating that the crystal growth rate increases much faster than a linear function with increasing supercooling. For the sake of convenience, below we consider separately the models of unsteady-state growth in one-component and binary supercooled melts, and supersaturated solutions.

(a). Growth rate in one-component melts

Let us introduce the radius Re of equivalent sphere where an individual crystal evolves with time. We assume that other crystals are randomly distributed in the metastable melt and grow inside their own equivalent spheres. In addition, growing particles do not interact and form the face-centred cubic lattice. Taking this into account, let us write down the corresponding mathematical model, that is

| 3.1 |

Here a represents the thermal diffusivity of liquid. The model (3.1) containing partial derivatives is a Stefan-type model with unknown moving boundary of the phase transition. This model was solved in [39] by means of the method of differential series. Keeping in mind two main contributions (see, for details, [39]), one can write out the crystal radius R(t) and growth rate dR/dt in the form of

| 3.2 |

where is the melt supercooling for a one-component system. An important point is that expressions (3.2) do not depend on an arbitrary value of the radius Re of equivalent sphere.

Expressing t from the first line of formula (3.2) and substituting the result into its second line, one can eliminate an explicit dependence on the growth time t and find the growth rate in terms of ΔT and R

| 3.3 |

A very important point is that the unsteady-state growth rate (3.3) contains expression (2.2) as a limiting case. Indeed, considering , we obtain

In other words, the growth rate (2.2) deduced in the case of steady-state temperature distribution around the growing particle follows from a generalized growth rate (3.3) in the limiting case of fine crystals, i.e. if . By this is meant that when crystals evolve and become large enough, frequently used approximation (2.2) becomes incorrect.

(b). Growth rate in binary melts

Let us now pay attention to the case of binary melt crystallization when the thermal and solute concentration fields in the liquid phase are described by means of unsteady-state transfer equations. As before, we suppose that the growth rate of an individual crystal is determined by the thermal and solute diffusion fluxes as well as by the difference of surface and phase transition temperatures. The temperature Tl and solute concentration Cl far from the crystal are considered to be fixed. Keeping all this in mind, we get

| 3.4 |

where, as before, .

This coupled thermo-solutal moving-boundary problem with nonlinear boundary conditions was solved in paper [40] using the methods of differential series and Laplace–Carson integral transform. Its solution in terms of R(t) and dR/dt reads as

| 3.5 |

where is the supercooling of a binary melt,

and Cl is the solute concentration far from the crystal. An important point is that solutions (3.5) transform to solutions (3.2) in the limiting case of a pure melt (if Cl = 0 and P = 1). Now eliminating t from expressions (3.5), we obtain the growth rate in terms of ΔT and R of the form

| 3.6 |

Note that expressions (3.3) and (3.6) coincide at P = 1 (Cl = 0).

In the limiting case of fine crystals , and for P ≈ 1, the unsteady-state growth law (3.6) transforms to its quasi-steady-state analogue (2.5) accordingly to the following estimates

where ΔT is determined for a binary melt.

(c). Growth rate in solutions

Now we consider the problem of crystal growth in a supersaturated solution with allowance for unsteady-state distribution of solute concentration in the liquid phase. Arguing by analogy with the above, we have the following statement of the problem for finding dynamic dependencies R(t) and dR/dt:

| 3.7 |

The solution of the moving-boundary problem (3.7) was constructed in paper [41] using the technique of differential series. Taking into account two main contributions, we arrive at the following solution [41]:

| 3.8 |

where ΔC = Cl − Cp. We note that relations (3.2) and (3.8) are formally analogous to each other, with substitutions of ΔT by ΔC and qT by qC. Therefore, the growth rate in solutions expressed through ΔC and R becomes

| 3.9 |

As before, the growth law (3.9) transforms to (2.7) in the limiting case of fine crystals as

(d). Analysis of growth rates and comparison with experiments

First, let us generalize the unsteady-state dynamical laws obtained in §3a–c. For this, we use the metastability degree Δ introduced in expression (2.8) and consider a more general case when Δ = Δ(t) due to the evolution of particulate assemblage in a metastable liquid. So, the first and second lines of dynamical laws (3.2), (3.5) and (3.8) determining the radius of evolving crystals and their growth rate take the form

| 3.10 |

and

| 3.11 |

where

The growth rates (3.3), (3.6) and (3.9) representing the functions of Δ and R read as

| 3.12 |

where

Note that expressions (3.11) and (3.12) determine the same growth rate by means of different dynamical variables.

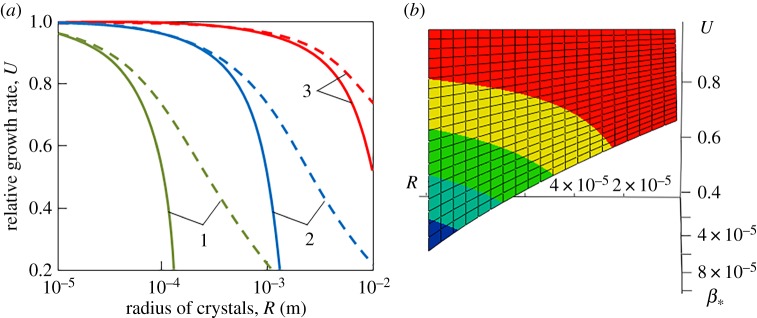

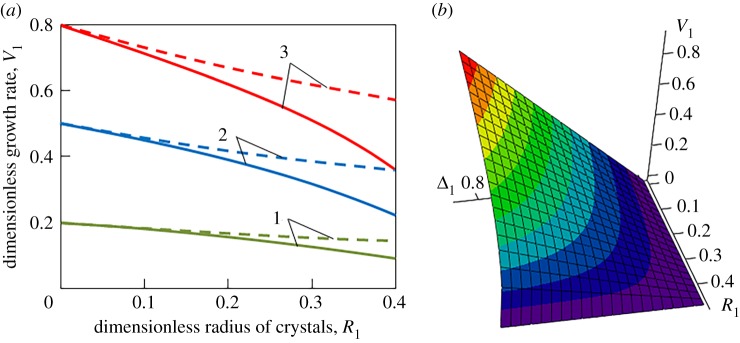

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the dynamical dependencies of the growth rate on the crystal radius and metastability degree. It is important to note that unsteady-state growth rate (3.12) essentially differs from its quasi-steady-state analogue (2.9) (compare the solid and dashed lines in figures 1a and 2a). In addition, such a discrepancy increases with increasing the radius of growing crystals, kinetic coefficient and metastability degree. Therefore, expression (2.9) for the quasi-steady-state growth law can be used only for fine crystals, small metastability degree (supercooling/supersaturation) and small kinetic coefficient. Figures 1b and 2b show that the growth rate increases with increasing the metastability degree and with decreasing the radius of crystals.

Figure 1.

(a) Relative growth rate versus crystal radius R at qT = 3.6 × 107 K s m−2 [40] and various kinetic coefficients (1), (2), and (3). The solid and dashed curves are plotted on the basis of growth rates (3.12) and (2.9), respectively. (b) Relative growth rate U as a function of crystal radius R (m) and kinetic coefficient . (Online version in colour.)

Figure 2.

(a) Dimensionless growth rate versus dimensionless crystal radius R1 = κiR (i = 1, 2, 3) at various dimensionless metastability degree Δ1 = Δ/(qT a): Δ1 = 0.2 (1), Δ1 = 0.5 (2), and Δ1 = 0.8 (3). The solid and dashed curves are plotted on the basis of growth rates (3.12) and (2.9), respectively. (b) Dimensionless growth rate V1 as a function of dimensionless metastability degree Δ1 and crystal radius R1. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 3 demonstrates nonlinear dynamics of crystal radius R(t) calculated accordingly to (3.10) and experimental data [42] on crystal growth of potassium aluminium sulphate 12H2O (potash alum) at various supersaturations. Note that the factor in parentheses of expression (3.10) describes the deviation of the shown dependencies from linear functions at large growth time t.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the theoretical growth radius (3.10) shown by the solid lines with experimental data [42] shown by symbols on potash alum crystal growth: Δ = 0.077 kmol (kg H2O)−1, (1), Δ = 0.062 kmol (kg H2O)−1, (2), , (3), and χ3 = 0.17 kg . (Online version in colour.)

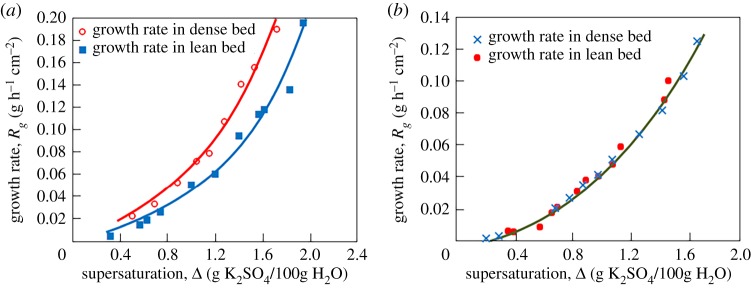

To compare the growth rate (3.11) with experiments [36] on nucleation and evolution of potassium sulphate crystals in a fluidized bed crystallizer, let us introduce the total mass M of solid particles as M = ρsNυ, where υ stands for the volume of a single particle, N represents their total number and ρs is the density of the growing phase. Assuming that all growing particles have spherical shape (υ = 4πR3/3, where R is the radius of crystal), we obtain the rate of mass gain dM/dt = 4πρsNR2dR/dt (here dR/dt is determined by formula (3.11)). Now designating through Rg = (4πR2N)−1dM/dt the relative mass gain, we have

| 3.13 |

This expression derived on the basis of the third line of dynamical law (3.11) is used to compare the unsteady-state growth rate with experimental data. To do this, we used the desupersaturation curve measured by Garside, Gaska and Mullin in [36]. This curve allowed us to find the function t(Δ), which is required to calculate the explicit dependence Rg(Δ) shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the theoretical growth rate (3.13) shown by solid lines with experimental data [36] shown by symbols on potassium sulphate crystals evolving in a fluidized bed crystallizer for dense and lean beds: panel (a) χ3 = 0.05 h−1 [Δ]−1, γ = 0.115 g h−1 cm−2 [Δ]−1 (dense bed) and χ3 = 0.055 h−1 [Δ]−1, γ = 0.08 g h−1 cm−2 [Δ]−1 (lean bed); panel (b) χ3 = 0.049 h−1 [Δ]−1, γ = 0.082 g h−1 cm−2 [Δ]−1 (dense and lean beds). (Online version in colour.)

Expression (3.13) can be rewritten in terms of the growth rate (3.12) as

| 3.14 |

This growth law is compared in figure 5 with experimental data [43] on citric acid monohydrate crystal growth in a liquid fluidized bed (experimental data on growth rate Rg, supersaturation Δ, and average size R of crystals are used, see fig. 2 and table 1 in [43]).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the theoretical growth rate (3.14) shown by the solid line with experimental data [43] shown by symbols on citric acid monohydrate crystals evolving in a liquid fluidized bed: κ3 = 180 m−1, γ = 6 kg of water h−1 m−2. (Online version in colour.)

A good agreement between theory and experiment confirms the applicability of non-stationary dynamic laws (3.11) and (3.12) for crystal growth rates.

4. Nonlinear dynamics of particulate assemblages in metastable liquids

In this section, we consider how the nonlinear growth rates (3.12) influence the nonlinear behaviour of particulate assemblages in metastable liquids. A complete analytical solution of the nonlinear integro-differential model that describes the evolution of system metastability and crystal-radius distribution function is constructed and analysed.

(a). Governing equations

Let us formulate a generalized set of governing equations, initial and boundary conditions assuming that the metastability degree Δ (supercooling or supersaturation) is determined for one-component melts or solutions by means of expression (2.8). The set of kinetic and balance equations for the crystal-size distribution function f(r, t) and metastability Δ takes the form [44–46]

| 4.1 |

where the radial coordinate is designated through r, the growth rate accordingly to (3.12) is given by , represents the radius of critical crystals that are capable of further growth (if the radius of the crystals is less than critical, they dissolve), Δ0 is the initial metastability degree (initial supercooling or supersaturation), and

| 4.2 |

Here ρm and Cm are the density and specific heat of the metastable liquid, LV and Cp designate the latent heat parameter and concentration at saturation. The coefficient of mutual Brownian diffusion defines the rate of fluctuations of growing crystals. For simplicity of analysis, we assume that is proportional to the growth rate [46–48], i.e.

| 4.3 |

where d1 is a pertinent factor.

Suppose that at the initial time, the liquid was instantly supercooled/supersaturated and its degree of metastability was Δ0. Suppose also that there were no crystals in the liquid phase at the initial moment of time. If this is really the case, the initial conditions take the form

| 4.4 |

Also, we consider the natural case that the metastable system does not contain infinitely large crystals, i.e.

| 4.5 |

The nucleation rate I(Δ) describes the flux of newly born crystals that overcome the nucleation barrier. The corresponding boundary condition reads as

| 4.6 |

Note that the nucleation rate depends on the mechanism of nucleation kinetics and takes the following form in the case of frequently used Meirs and Weber–Volmer–Frenkel–Zel’dovich (WVFZ) modes:

| 4.7 |

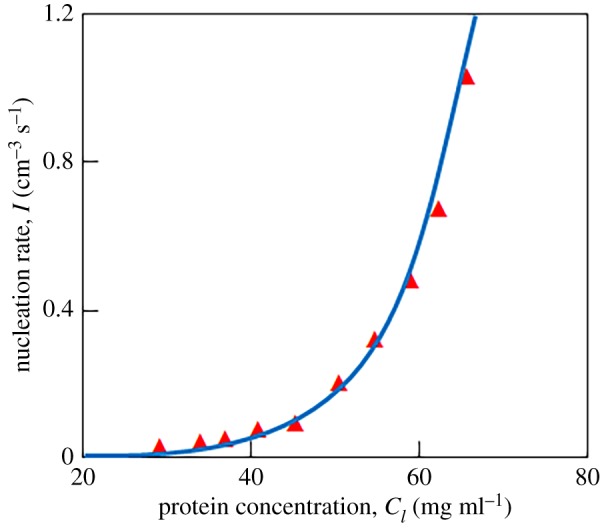

where p and represent constants different for supercooled melts (sm) and supersaturated solutions (ss) as well as for the Meirs and WVFZ kinetics (see, for example, [49]). Figure 6 compares the nucleation rate determined according to the Meirs kinetics with experiments on homogeneous nucleation of lysozyme crystals. As is easy to see, the theory is in good agreement with experimental data.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the nucleation rate (4.7) shown by the solid line (Meirs kinetics) with experimental data [50] shown by symbols on nucleation of lysozyme crystals: , [Δ−p], p = 6.18. (Online version in colour.)

(b). A complete analytical solution

For the sake of simplicity, we further consider that the radius of a critical crystal is zero. Introducing the dimensionless coordinate s = r/l0, time τ = t/t0 and metastability degree w = Δ/Δ0 so that (the space and time scales l0 and t0 are given below), we have the following dimensionless law for the growth rate of individual crystal:

| 4.8 |

Integrating this equation and keeping in mind that s = 0 at , where is the time of nucleation of a growing particle, we arrive at

| 4.9 |

Now to rewrite the model equations (4.1)–(4.7) in dimensionless form, let us choose the following designations

Taking this into account, we come to the following nonlinear problem:

| 4.10 |

| 4.11 |

| 4.12 |

Note that expressions (4.12) determine the Meirs and WVFZ nucleation kinetics, respectively.

The method for solving the problem (4.10)–(4.12) is described in papers [44,45,51]. Using the theory developed in these works, let us write down the final result in the form

| 4.13 |

Here the first two lines of expression (4.13) determine the dimensionless distribution function F(s, x), and the third line defines dependencies w(x) and τ(x). Here the following designations are introduced

| 4.14 |

An important point is that the left-hand side of expression (4.13) for w can be integrated in an explicit form if we are dealing with the case of Meirs kinetic mechanism. The result reads as

| 4.15 |

Let us especially highlight that expressions (4.13) represent the analytical solution in a parametric form (the modified time x plays the role of this parameter).

(c). Approximate solution for slow fluctuations in crystal growth rates

It is significant that a complete analytical solution (4.13)–(4.15) can be substantially simplified in the case of unessential random fluctuations in particle growth rates (when the last term in the kinetic equation (4.1) for the particle-size distribution function does not play an important role). In this case, the problem contains the small parameter u0. Taking this into account, we get from (4.14) and (4.15) the following approximate expressions (κl0 ≪ 1):

| 4.16 |

Now combining (4.15) and (4.16), we come to a simplified formula for the metastability degree expressed in terms of its inverse function

| 4.17 |

Changing the variable of integration in expression (4.13) for τ(x) as dx1 = (dx1/dw1) dw1 and substituting g0(x1) from (4.14), we finally obtain

| 4.18 |

where x1(w1) is defined by expression (4.17).

This dynamical law determines a direct dependence between the metastability degree w (supercooling or supersaturation) and dimensional time τ in terms of the inverse function τ(w). Thus, the approximate approach under consideration enables us to eliminate a parametric dependence of our solution on the modified time x.

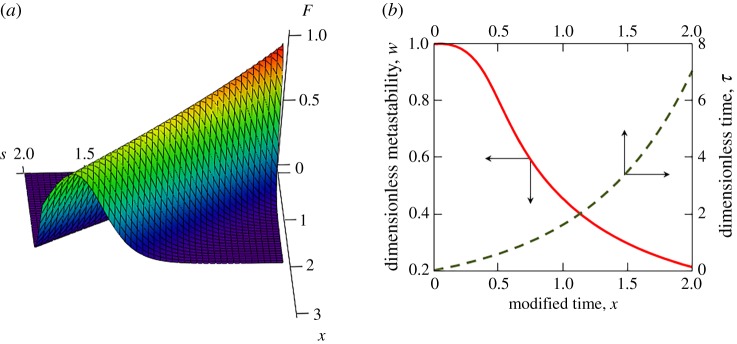

(d). Behaviour of solutions

Figure 7 demonstrates the parametric solution (4.13) for the Meirs nucleation kinetics. As is easily seen, the distribution function has a maximum at certain values of particle radius s and modified time x. This maximum point moves to larger s with increasing x (or with increasing dimensionless time τ). As this takes place, the metastability degree w reduces with time as a result of the crystal growth process. What is more, the dimensionless time increases with increasing parameter x.

Figure 7.

(a) The particle-size distribution function F versus the size of crystals s and modified time x. (b) The dimensionless metastability degree w and dimensionless time τ as functions of the modified time x. The model parameters used in calculations are [49]: LV = 7 × 109 J m−3, ρm = 7 × 103 kg m−3, Cm = 840 J kg−1 K−1, Δ0 = 300 K, I0 = 109 m−3 s−1, , λl = 63 J m−1 K−1 s−1, u0 = 10−2, p = 6. (Online version in colour.)

Eliminating parameter x by means of the dependence τ(x), our solution (4.13) can be represented in terms of real time τ instead of modified time x. This solution is shown in figure 8 with the help of dashed and solid lines. The distribution function represents a bell-shaped curve that decreases with increasing the real time τ. As this takes place, this function shifts to larger sizes s of crystals (compare the dashed and solid lines at τ = 1 and τ = 2) due to the desupercooling/desupersaturation process (w decreases) and, as a consequence, due to the almost absent nucleation of new particles. The number of larger particles herewith increases as a result of the crystal growth process (since the distribution function moves to the right).

Figure 8.

(a) The particle-size distribution function F versus the size of crystals s at various times τ. (b) The dimensionless metastability degree w as a function of time τ. The model parameters used in calculations correspond to figure 7. The dashed curves illustrate our solution (4.13) with allowance for the nonlinear growth law (see, expressions (3.12)). The solid lines demonstrate the same solution shown for the linear growth rate . (Online version in colour.)

An important role of nonlinear growth rates (3.12) is clearly seen in figure 8 by comparing the dashed and solid curves. Indeed, we also demonstrate here our solution (4.13) calculated using the linear growth law (solid lines in figure 8). As the nonlinear expressions (4.13) lead to slower growth rates V (in comparison with the linear law ), their corresponding metastability degree (dashed curve) lies above the solid curve (shown for Vlin). As this takes place, the distribution function (dashed line) is shifted to the left side in comparison with F for Vlin (solid line) and its maximum lies above. This means that the actual metastable liquid contains smaller solid particles than the liquid where the crystals are modelled using the linear law .

Figures 9 and 10 compare our analytical solution (4.18) with experiments on crystal growth in citric acid and potassium sulphate solutions [36,52] as well as in solutions for bovine and porcine insulin [53,54]. Here the solid and dashed lines demonstrate the desupersaturation law (4.18) and symbols illustrate the aforementioned experimental results. Note that good agreement between the theory and experiments confirms the validity of dynamical theory developed in §4c.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the metastability degree (4.18) shown by the solid line (Meirs kinetics) with experimental data [52] (filled symbols) for various initial supersaturations and with experimental data [36] (open circles): b = 4, p = 1.3, κ = 0. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 10.

Comparison of the metastability degree (4.18) shown by the solid line (Meirs kinetics) with experimental data [53,54] shown by symbols on crystallization of bovine and porcine insulin from solution: b = 0.02, p = 2.3, κ = 0 (bovine insulin), and b = 0.08, p = 1.9, κ = 0 (porcine insulin). (Online version in colour.)

5. Summary and conclusion

The present paper analyses the quasi-steady-state and unsteady-state growth laws for spherical crystals evolving in supercooled and supersaturated liquids. We summarize the corresponding mathematical models and represent their solutions in terms of dynamical dependencies for crystal radius and its growth rate. Comparing the steady- and unsteady-state laws we conclude that the corresponding dependencies substantially differ from each other with increasing the radius of evolving particles, supercooling/supersaturation and kinetic coefficient. An important point of unsteady-state dynamic laws (3.10)–(3.12) is that they describe nonlinear non-stationary growth curves for crystal radii and their growth rates known from numerous experimental data. What is more, the unsteady-state growth theory presented in §3 contains the quasi-steady-state theory (§2) as a limiting case of fine crystals growing in a metastable liquid.

Next, we formulate the model for evolution of a polydisperse ensemble of crystals in supercooled or supersaturated systems with allowance for the unsteady-state growth law (3.12), which, in turn, changes the kinetic equation for the crystal-size distribution function and the boundary condition for the flux of particles that overcame the nucleation barrier and became capable of further growth. As this takes place, the metastability degree (supercooling or supersaturation) also changes through the balance equation that depends on the distribution function. A complete solution of this model is constructed in a parametric form for arbitrary nucleation rates. The obtained analytical solution demonstrates that the crystal-size distribution function represents a bell-shaped curve which is shifted to the direction of smaller particle sizes if we are dealing with a more actual case of unsteady-state crystal growth rates. In other words, the metastable system contains smaller crystals than in the case of quasi-steady-state growth rates. A particular case of Meirs nucleation kinetics is considered in more detail. An approximate analytical solution found for the case of small random fluctuations in the growth rates of crystals allows us to express an explicit evolutionary law for the metastability degree that describes desupercooling or desupersaturation of a metastable liquid. We also demonstrate that the obtained dynamical dependence for metastability reduction well describes numerous experimental data on crystal growth in citric acid and potassium sulphate solutions [36,52] as well as in solutions for bovine and porcine insulin [53,54].

As a final note, let us especially highlight that nucleation and crystal growth in metastable liquids can be complicated by directional growth of dendrite-like structures in the presence of temperature and solute concentration gradients. In this case, the phase transition occurs with a mushy layer that divides pure solid and liquid material. This layer filled with evolving solid structures in a metastable liquid moves with a time-dependent growth velocity. Therefore, for a more accurate description of the mushy layer dynamics in materials science [55–58] and geophysics [59–63] it is important to develop its theory with allowance for the present analysis where nucleation and growth of solid phase particles occur in an unsteady-state manner.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the present review article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation(grant no. 18-19-00008).

Reference

- 1.Buyevich YA, Goldobin YM, Yasnikov GP. 1994. Evolution of a particulate system governed by exchange with its environment. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 37, 3003–3014. ( 10.1016/0017-9310(94)90354-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buyevich YA, Alexandrov DV. 2017. On the theory of evolution of particulate systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 192, 012001 ( 10.1088/1757-899X/192/1/012001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelton KF, Greer AL. 2010. Nucleation in condensed matter: applications in materials and biology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrov DV. 2014. Nucleation and growth of crystals at the intermediate stage of phase transformations in binary melts. Philos. Mag. Lett. 94, 786–793. ( 10.1080/09500839.2014.977975) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubrovskii VG. 2014. Nucleation theory and growth of nanostructures. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexandrov DV. 2015. On the theory of Ostwald ripening: formation of the universal distribution. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 48, 035103 ( 10.1088/1751-8113/48/3/035103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow DA. 2017. Theory of the intermediate stage of crystal growth with applications to insulin crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 470, 8–14. ( 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2017.03.053) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makoveeva EV, Alexandrov DV. 2018. A complete analytical solution of the Fokker-Planck and balance equations for nucleation and growth of crystals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170327 ( 10.1098/rsta.2017.0327) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov AA, Alexandrova IV, Alexandrov DV. 2019. Phase transformations in metastable liquids combined with polymerization. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180215 ( 10.1098/rsta.2018.0215) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanov AA, Alexandrov DV, Alexandrova IV. 2020. Dissolution of polydisperse ensembles of crystals in channels with a forced flow. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378, 20190246 ( 10.1098/rsta.2019.0246) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullin JW, Gaska C. 1973. Potassium sulfate crystal growth rates in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Eng. Data 18, 217–220. ( 10.1021/je60057a030) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennema P. 1976. Theory and experiment for crystal growth from solution: implications for industrial crystallization. In Industrial crystallization (ed. JW Mullin), pp. 91–112. Boston, MA: Springer ( 10.1007/978-1-4615-7258-9.9) [DOI]

- 13.Lifshitz EM, Pitaevskii LP. 1981. Physical kinetics. Oxford, UK: Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slezov VV. 2009. Kinetics of first-order phase transitions. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexandrov DV. 2016. On the theory of Ostwald ripening in the presence of different mass transfer mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 91, 48–54. ( 10.1016/j.jpcs.2015.12.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexandrov DV, Ivanov AA, Alexandrova IV. 2019. The influence of Brownian coagulation on the particle-size distribution function in supercooled melts and supersaturated solutions. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 52, 015101 ( 10.1088/1751-8121/aaefdc) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexandrov DV, Alexandrova IV. 2020. From nucleation and coarsening to coalescence in metastable liquids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378, 20190247 ( 10.1098/rsta.2019.0247) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanov AO, Zubarev AYu. 1998. Non-linear evolution of a system of elongated drop-like aggregates in a metastable magnetic fluid. Physica A 251, 348–367. ( 10.1016/S0378-4371(97)00561-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandrov DV. 2016. Mathematical modelling of nucleation and growth of crystals with buoyancy effects. Philos. Mag. Lett. 96, 132–141. ( 10.1080/09500839.2016.1177222) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buyevich YuA, Natalukha IA. 1994. Unsteady processes of combined polymerization and crystallization in continuous apparatuses. Chem. Eng. Sci. 49, 3241–3247. ( 10.1016/0009-2509(94)E0052-R) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volmer U, Raisch J. 2001. H∞-Control of a continuous crystallizer. Control Eng. Practice 9, 837–845. ( 10.1016/S0967-0661(01)00048-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachah A, Noll D, Espitalier F, Baillon F. 2015. A mathematical model for continuous crystallization. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 39, 1101–1120. ( 10.1002/mma.3553) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexandrov DV. 2014. Nucleation and crystal growth kinetics during solidification: the role of crystallite withdrawal rate and external heat and mass sources. Chem. Eng. Sci. 117, 156–160. ( 10.1016/j.ces.2014.06.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makoveeva EV, Alexandrov DV. 2019. Effects of nonlinear growth rates of spherical crystals and their withdrawal rate from a crystallizer on the particle-size distribution function. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180210 ( 10.1098/rsta.2018.0210) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strickland-Constable RF. 1968. Kinetics and mechanisms of crystallization. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makoveeva EV, Alexandrov DV. 2018. An analytical solution to the nonlinear evolutionary equations for nucleation and growth of particles. Philos. Mag. Lett. 98, 199–208. ( 10.1080/09500839.2018.1522459) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalmers B. 1959. Physical metallurgy. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skripov VP. 1974. Metastable liquids. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chernov AA. 1984. Modern crystallography III. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexandrov DV. 2001. Solidification with a quasiequilibrium two-phase zone. Acta Mater. 49, 759–764. ( 10.1016/S1359-6454(00)00388-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aseev DL, Alexandrov DV. 2006. Directional solidification of binary melts with a non-equilibrium mushy layer. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 49, 4903–4909. ( 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2006.05.046) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aseev DL, Alexandrov DV. 2006. Nonlinear dynamics for the solidification of binary melt with a nonequilibrium two-phase zone. Phys.-Dokl. 51, 291–295. ( 10.1134/S1028335806060024) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandrov DV. 2014. Nucleation and crystal growth in binary systems. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 47, 125102 ( 10.1088/1751-8113/47/12/125102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexandrov DV, Ivanov AA, Alexandrova IV. 2018. Analytical solutions of mushy layer equations describing directional solidification in the presence of nucleation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170217 ( 10.1098/rsta.2017.0217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullin JW, Gaska C. 1969. The growth and dissolution of potassium sulphate crystals in a fluidized bed crystallizer. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 47, 483–489. ( 10.1002/cjce.5450470514) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garside J, Gaska C, Mullin JW. 1972. Crystal growth rate studies with potassium sulphate in a fluidized bed crystallizer. J. Cryst. Growth 13/14, 510–516. ( 10.1016/0022-0248(72)90290-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullin JW, Osman MM. 1973. Nickel ammonium sulfate crystal growth rates in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Eng. Data 18, 353–355. ( 10.1021/je60059a035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. 1992. Growth kinetics and mechanism of glycine crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 121, 33–38. ( 10.1016/0022-0248(92)90172-F) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexandrov DV. 2018. Nucleation and evolution of spherical crystals with allowance for their unsteady-state growth rates. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 51, 075102 ( 10.1088/1751-8121/aaa5b7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexandrov DV, Alexandrova IV. 2019. On the theory of the unsteady-state growth of spherical crystals in metastable liquids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180209 ( 10.1098/rsta.2018.0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexandrov DV, Nizovtseva IG, Alexandrova IV. 2019. On the theory of nucleation and nonstationary evolution of a polydisperse ensemble of crystals. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 128, 46–53. ( 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.08.119) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toyokura K, Yamazoe K, Mogi J, Yago N, Aoyama Y. 1976. Secondary nucleation of potash alum. In Industrial crystallization (ed. JW Mullin), pp. 41–49. Boston, MA: Springer ( 10.1007/978-1-4615-7258-9.4) [DOI]

- 43.Laguerie C, Angelino H. 1976. Growth rate of citric acid monohydrate crystals in a liquid fluidized bed. In Industrial crystallization (ed. JW Mullin), pp. 135–143. Boston, MA: Springer ( 10.1007/978-1-4615-7258-9.12) [DOI]

- 44.Alexandrov DV, Nizovtseva IG. 2014. Nucleation and particle growth with fluctuating rates at the intermediate stage of phase transitions in metastable systems. Proc. R. Soc. A 470, 20130647 ( 10.1098/rspa.2013.0647) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexandrov DV. 2014. On the theory of transient nucleation at the intermediate stage of phase transitions. Phys. Lett. A 378, 1501–1504. ( 10.1016/j.physleta.2014.03.051) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexandrov DV, Malygin AP. 2014. Nucleation kinetics and crystal growth with fluctuating rates at the intermediate stage of phase transitions. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 22, 015003 ( 10.1088/0965-0393/22/1/015003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melikhov IV, Belousova TYa, Rudnev NA, Bludov NT. 1974. Fluctuation in the rate of growth of monocrystals. Kristallografiya 19, 1263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buyevich YA, Ivanov AO. 1993. Kinetics of phase separation in colloids II. Non-linear evolution of a metastable colloid. Physica A 193, 221–240. ( 10.1016/0378-4371(93)90027-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexandrov DV, Malygin AP. 2013. Transient nucleation kinetics of crystal growth at the intermediate stage of bulk phase transitions. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 46, 455101 ( 10.1088/1751-8113/46/45/455101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filobelo LF, Galkin O, Vekilov PG. 2005. Spinodal for the solution-to-crystal phase transformation. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 014904 ( 10.1063/1.1943413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexandrov DV, Nizovtseva IG. 2019. On the theory of crystal growth in metastable systems with biomedical applications: protein and insulin crystallization. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180214 ( 10.1098/rsta.2018.0214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mullin JW, Leci CJ. 1972. Desupersaturation of seeded citric acid solutions in a stirred vessel. AIChE Symp. Ser. 68, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlichtkrull J. 1957. Insulin crystals. V. The nucleation and growth of insulin crystals. Acta Chem. Scand. 11, 439–460. ( 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.11-0439) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schlichtkrull J. 1957. Insulin crystals. VII. The growth of insulin crystals. Acta Chem. Scand. 11, 1248–1256. ( 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.11-1248) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borisov VT. 1987. Theory of two-phase zone of a Metal ingot. Moscow, Russia: Metallurgiya Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexandrov DV, Ivanov AA. 2009. The Stefan problem of solidification of ternary systems in the presence of moving phase transition regions. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 108, 821–829. ( 10.1134/S1063776109050100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fowler AC. 1985. The formation of freckles in binary alloys. IMA J. Appl. Math. 35, 159–174. ( 10.1093/imamat/35.2.159) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nizovtseva IG, Alexandrov DV. 2020. The effect of density changes on crystallization with a mushy layer. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378, 20190248 ( 10.1098/rsta.2019.0248) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Worster MG, Huppert HE, Sparks RSJ. 1990. Convection and crystallization in magma cooled from above. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 101, 78–89. ( 10.1016/0012-821X(90)90126-I) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexandrov DV, Nizovtseva IG. 2008. Nonlinear dynamics of the false bottom during seawater freezing. Dokl. Earth Sci. 419, 359–362. ( 10.1134/S1028334X08020384) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alexandrov DV, Bashkirtseva IA, Malygin AP, Ryashko LB. 2013. Sea ice dynamics induced by external stochastic fluctuations. Pure Appl. Geophys. 170, 2273–2282. ( 10.1007/s00024-013-0664-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huguet L, Alboussière T, Bergman MI, Deguen R, Labrosse S, Lesoeur G. 2016. Structure of a mushy layer under hypergravity with implications for Earth’s inner core. Geophys. J. Int. 204, 1729–1755. ( 10.1093/gji/ggv554) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexandrov DV, Bashkirtseva IA, Ryashko LB. 2018. Nonlinear dynamics of mushy layers induced by external stochastic fluctuations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170216 ( 10.1098/rsta.2017.0216) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.