Abstract

Verbal fluency is commonly used to evaluate cognitive dysfunction in a variety of neuropsychiatric diseases, yet the neurobiology underlying performance of this task is incompletely understood. Electrocorticography (ECoG) provides a unique opportunity to investigate temporal activation patterns during cognitive tasks with high spatial and temporal precision. We used ECoG to study high gamma activity (HGA) patterns in patients undergoing presurgical evaluation for intractable epilepsy as they completed an overt, free-recall verbal fluency task. We examined regions demonstrating changes in HGA during specific timeframes relative to speech onset. Early pre-speech high gamma activity was present in left frontal regions during letter fluency and in bifrontal regions during category fluency. During timeframes typically associated with word planning, a distributed network was engaged including left inferior frontal, orbitofrontal and posterior temporal regions. Peri-Rolandic activation was observed during speech onset, and there was post-speech activation in the bilateral posterior superior temporal regions. Based on these observations in the context of prior studies, we propose a model of neocortical activity patterns underlying verbal fluency.

Keywords: electrocorticography (ECoG), high-gamma, verbal fluency, epilepsy, word production, cognitive search

1. Introduction

Verbal fluency testing is a commonly used tool to evaluate cognitive dysfunction in a variety of neurologic and psychiatric diseases. Patients are typically given a criterion and instructed to verbally produce as many fitting exemplars as they can within a 60 second timeframe. The most common criteria are categories (e.g. animals, supermarket items) wherein exemplars should be members of the designated category, or letters (e.g. F, A, S) wherein exemplars should begin with the designated letter. Inability to produce an adequate number of exemplars in the category-motivated condition indicates a semantic verbal fluency deficit and can be seen in frontal or temporal lobe lesions, schizophrenia, dementias and left temporal lobe epilepsy (Araujo et al., 2011; Ehlis, Herrmann, Plichta, & Fallgatter, 2007; Metternich, Buschmann, Wagner, Schulze-Bonhage, & Kriston, 2014). Letter-motivated (phonemic) fluency deficits are seen in frontal lobe lesions, left frontal lobe epilepsy, dementias and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Andreou & Trott, 2013; Ehlis et al., 2007; Metternich et al., 2014). Verbal fluency can be an important aspect of language localization and diagnostic efforts across a variety of disorders, and an understanding of the neural substrates underlying its performance can inform both invasive and noninvasive strategies to improve language function.

Verbal fluency tasks differ from other word production tasks (e.g. picture naming, verb generation or sentence completion) in that individual exemplars are not stimulus-locked, but rather depend on a concurrent, rule-based, free recall process. People tend to produce exemplars in clusters of semantically or phonemically related items. The underlying cognitive search process is thus postulated to include two major components: identification of clusters of exemplars fitting a given sub-criterion, and execution of an overarching control function, possibly in left inferior frontal gyrus, that switches among sub-criteria once a particular cluster has been exhausted (Hirshorn & Thompson-Schill, 2006; Shao, Janse, Visser, & Meyer, 2014; Troyer & Moscovitch, 2006).

Despite the widespread use of this test in clinical practice, there is limited understanding of the neurophysiologic activity underlying its performance. Positron-emission tomography (PET) studies before and during letter-cued verbal fluency tasks have demonstrated increased metabolism primarily in bitemporal regions (Boivin et al., 1992; Parks et al., 1988). Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), activation has been demonstrated in the bilateral superior and left inferior frontal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), left insula and the right cerebellum (Abrahams et al., 2003; Li et al., 2017; Schlösser et al., 1998). Letter-motivated fluency may depend more heavily on the left inferior frontal gyrus (in particular BA44) by comparison to category-driven tasks, while left occipitotemporal cortex demonstrates the reverse affinity (Birn et al., 2010; Heim et al., 2009; Paulesu et al., 2016). In addition to neocortical regions, bilateral hippocampi show increased blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) activity and increased connectivity to semantic language networks in category-cued but not letter-cued verbal fluency (Glikmann-Johnston, Oren, Hendler, & Shapira-Lichter, 2015).

In contrast to fMRI findings, similar comparisons using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) suggest greater activation in the prefrontal regions bilaterally during letter-motivated fluency, and in the left (inferior) frontal regions during category-motivated fluency tasks (Tupak et al., 2012). The reasons for this distinction are not clear, but may relate to differences in methodology, task difficulty, age or sex of the participants included, all of which may influence the observed activation patterns (Kahlaoui et al., 2012; Troyer, Moscovitch, & Winocur, 1997).

Traditional neuroimaging modalities provide important insights to the neuroanatomical substrates underlying verbal fluency tasks, but they lack the resolution necessary to probe the temporal dynamics of cognitive subprocesses supporting verbal fluency tasks. One study did use magnetic source imaging (MSI) to investigate temporal activation patterns of selected cortical regions in a paced version of the verbal fluency test (Billingsley et al., 2004). The authors noted earlier activation in precentral and supplementary motor regions compared to inferior frontal or insular regions. Their results also suggested a peak in inferior frontal gyrus/anterior insula activity at about 600 milliseconds after letter stimuli, which was not present after categorical stimuli. To our knowledge, no study to date has examined the spatial and temporal neuronal activation patterns associated with generation of exemplars in a self-paced verbal fluency test, as is commonly administered in clinical practice.

High gamma power derived from ECoG recordings is a useful metric for examining the physiological patterns underlying cognitive processes with excellent spatial and exquisite temporal resolution (Llorens, Trébuchon, Liégeois-Chauvel, & Alario, 2011). This measure has previously been used to elucidate patterns in auditory processing (Crone, Boatman, Gordon, & Hao, 2001; Nourski et al., 2014; Nourski, Steinschneider, Rhone, & Howard III, 2017), word repetition (Towle et al., 2018), picture naming, verb generation (Edwards et al., 2010) and other cognitive functions. The technique allows investigators to probe neuronal activity with the same temporal resolution within which related cognitive functions are postulated to occur. Gamma oscillations have been investigated in a free recall memory paradigm, and shown to predict successful memory formation during encoding and to distinguish true from false memories at recall (Henin et al., 2019; Sederberg, Kahana, Howard, Donner, & Madsen, 2003; Sederberg et al., 2007). However, no study to date has used high gamma activity to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of the verbal fluency task, which combines a free recall format with long-term memory and word production processes, in real time.

We used ECoG high gamma activity to investigate the functional language network architecture during an overt, self-paced verbal fluency task in patients with epilepsy. We postulated that individual responses would be associated with pre-utterance activation in the precentral and inferior frontal region, and post-utterance activation in the superior temporal gyrus, as has been demonstrated in prior studies of speech production (Crone, Hao, et al., 2001; Edwards et al., 2010; Pei et al., 2011). We further expected that distinctions between the category fluency condition and the letter fluency condition would exist primarily during timeframes attributable to cognitive search. Based on our observations, we propose a model for word production during this frequently used but incompletely understood test of cognitive function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

We studied seven patients undergoing pre-surgical intracranial EEG monitoring for drug-resistant epilepsy. Subdural strip, grid, and in some cases depth electrodes were implanted in left and right hemispheres based on clinical necessity. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participating.

We localized electrodes for each participant by co-registering post-operative CT with post-operative MRI, and transforming the resulting image into MNI152 space. The Harvard-Oxford Atlas provided through the FMRIB Software Library (Jenkinson, Beckmann, Behrens, Woolrich, & Smith, 2012) was used to assign an anatomical cortical or subcortical label to each electrode contact. Electrode localizations were confirmed by visual inspection by a trained neuroradiologist.

2.2. Task Procedures

Six category stimuli and six letter stimuli were presented to each participant, interspersed with six resting blocks during which participants were requested to remain quiet with eyes closed for 60 seconds (Figure 1). The blocks were presented in varying orders for each participant, such that there were no two resting blocks in succession, and that there were no more than two task blocks of the same condition (letter or category) in succession. During task blocks, participants were presented with either a category or a single letter (depending on the block type) and instructed to overtly produce as many words as possible fitting that category or starting with that letter in a 60 second period. Stimuli were presented verbally to ensure comprehension. Participants were instructed to avoid repeating words and to keep eyes closed during the entire task. To reduce distraction and frustration, participants were allowed to ‘pass’ to end blocks early in cases where they had exhausted all the words they could imagine. Stimuli were selected based on those commonly referenced in the verbal fluency literature. The following category stimuli were chosen: animals, fruits, tools, supermarket items, vehicles and body parts. The following letter stimuli were chosen: F, A, S, C, P, L. The stimuli were presented in varying orders for each participant, such that there were no more than two resting blocks in succession, and that there were no more than two task blocks of the same condition (letter or category) in succession. The entire procedure, including rest blocks, instructions and clarifications, typically occurred over 20-25 minutes for each participant.

Figure 1:

Stimulus Presentation Timeline.

Participants were instructed to lay quietly with eyes closed. Six CATEGORY blocks (indicated in red), 6 LETTER blocks (blue), and 6 REST blocks (green). Stimuli were presented orally to ensure comprehension, and delivered in varying order such that no two rest blocks were sequentially together, and that there were no more than two task blocks of the same type. For each stimulus, participants were given 60 seconds to overtly produce as many exemplars as possible fitting the stimulus criterion, avoiding proper names and repetitions. To minimize frustration and distraction, participants were allowed to ‘pass’ to end blocks early if they felt they had exhausted their mental lexicon.

2.3. EEG Collection and Behavioral Recording

Electrocorticography (ECoG) data were sampled at 2048 samples per second using a Neuralynx Data Acquisition machine (participant 1) or at 500 or 1024 samples/second (other participants, as determined by the clinical neurophysiology team) using a 128 channel Natus XLTek data acquisition machine. Data were subsequently exported in NLX or European Data Format (EDF), deidentified and uploaded to the International Epilepsy Electrophysiology Portal (ieeg.org) for annotation, review and analysis. Overt verbal responses were recorded digitally using an external digital recorder and audio files were manually synchronized to the EEG recording via simultaneous timestamps. Audio files were transcribed manually and speech onsets marked using Audacity (http://www.audacityteam.org/) and the resulting annotations were merged with the EEG recording in the international electrophysiology portal (ieeg.org) using proprietary MATLAB scripts.

2.4. EEG Processing

Intracranial EEG recordings were visually inspected and segments containing artifact, seizures or epileptiform discharges were discarded. We used common average referencing to reduce effects of correlated noise in the signal and spatial bias from the reference electrode. Data in category-driven and letter-driven blocks were then organized into 2-second epochs associated with each word utterance, ranging from 1.25 seconds pre-utterance to 0.75 seconds post-utterance. To reduce overlap of signal from adjacent words, we removed epochs containing words with onset less than 1 second following or less than 0.5 seconds prior to another word. We also organized resting blocks into non-overlapping 2s epochs to establish a baseline. Next, we used the Thomson multitaper method (Thomson, 1982) to compute spectral power using a time-halfbandwidth power of 7 and 13 Slepian tapers. For semantic and phonemic conditions, we computed the time-varying power spectrum across each epoch, using 200ms overlapping windows with 10ms spacing. This yielded 181 windows for analysis. For the rest condition, we computed the mean power spectrum across the entire epoch. The resulting spectra were averaged across the gamma frequency range of 70-110 Hz, and subsequently log-transformed. To allow for consistent scaling across channels, we then normalized the time-varying gamma powers in the semantic and phonemic conditions by the rest period power as follows:

| Eq. (1) |

where t is the normalized gamma power, x is the original gamma power, and μrest and σrest are the mean and standard deviation of the gamma power in the rest condition, respectively.

2.5. Data Analysis

We performed our primary analyses at the individual participant level to account for the distinct sampling patterns dictated by each participant’s clinical requirements, the likelihood that each participant would have unique network topologies subserving cognitive function, and the spatial precision with which high gamma activity is often observed (Cervenka et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2010).

We had 6 category stimuli and 6 letter stimuli, with multiple utterances for each stimulus. For the same stimulus type (category or letter), we aggregated across all utterances and stimuli to determine the average gamma activity at each of the 181 time points. Traces of this averaged activity over the 2-second period are demonstrated in Figures 3 and 4. We consider activity to be significantly elevated above rest when the mean of the log-normalized activity is greater than 1.96 times the mean log of high gamma activity at rest in the same electrode. Although arbitrary, this threshold was used to correspond to the quantile of the normal distribution that has a two-sided probability in the tail of 5%. We did not apply a strict threshold of number of consecutive windows across which the mean t-score must be above threshold, because at this stage of the analysis we aimed to evaluate all contacts that had any activity over the chosen threshold.

Figure 3:

Spatiotemporal High Gamma Activity Patterns during Verbal Fluency (Left Hemispheric Implant).

Temporal activation patterns at electrodes with suprathreshold high gamma activity during specific time periods with respect to speech utterance onset for participant 1. High gamma power is log-normalized to resting power at each electrode contact. Mean high gamma tracings indicated by bold lines with 95% confidence intervals indicated by pastel shades. Activity exceeding the t =1.96 threshold relative to resting baseline is identified by colored bars across the top of each summary graph. Panels A, D, G and J indicate electrode localizations for the matching colored high gamma activity tracings in the remaining panels. Panels B and C illustrate patterns for electrodes active more than 750ms prior to speech onset. Activity during this timeframe, which is earlier than canonical speech production processes are expected to occur, may thus represent cognitive search. Panels E and F show tracings with peak activity within 600ms prior to speech onset, corresponding to a timeframe previously ascribed to word planning (phonological and phonemic encoding). This occurs in distributed regions of prefrontal and posterior temporal cortices, and was seen only in left hemispheric implants. Panels H and I depict electrodes with activity that begins rising 200-300ms prior to speech onset and peaks 50-250ms after onset. These likely represent articulatory motor planning in the peri-Rolandic cortices. Panels K and L show posterior temporal activity that peaks 400-500ms after utterance onset, possibly representing auditory feedback processing.

Figure 4:

Spatiotemporal High Gamma Activity Patterns during Verbal Fluency (Right Hemispheric Implant).

Temporal activation patterns at selected electrodes with suprathreshold high gamma activity during specific time periods with respect to speech utterance onset for participant 6. High gamma power is log-normalized to resting power at each electrode contact. Mean high gamma tracings indicated by bold lines with 95% confidence intervals indicated by pastel shades. Activity exceeding the t =1.96 threshold relative to resting baseline is identified by colored bars across the top of each summary graph. Panels A, D and G indicate electrode localizations for the corresponding colored high gamma activity tracings in the remaining panels. Panels B and C illustrate patterns for electrodes active more than 750ms prior to speech onset. Activity during this timeframe, which is earlier than canonical speech production processes are expected to occur, may thus represent cognitive search. Right hemispheric electrodes demonstrating suprathreshold activity during the letter-motivated cognitive search timeframe were sparse. Electrodes that were active during category-motivated cognitive search timeframes tended to remain active during the post-utterance timeframe as well. Panels E and F depict electrodes with activity that begins rising 200-300ms prior to speech onset and peaks 50-250ms after onset. These likely represent articulatory motor planning in the peri-Rolandic cortices. Panels H and I show posterior temporal activity that peaks 400-500ms after utterance onset, possibly representing auditory feedback processing.

To determine the times with respect to speech utterance onset at which individual electrodes showed significant differences between high gamma activity for letter stimuli versus high gamma activity for category stimuli, we then selected four epochs within the 2-second periods and averaged the gamma activity in each of these four epochs. Epochs were selected based on prior literature to reflect timeframes relative to speech onset wherein salient language production processes are postulated to occur, without significant contribution of other processes. Assuming speech onset at 0ms, these timeframes were as follows:

Early: −850ms to −600ms relative to speech onset for cognitive search

Pre-Utterance: −250ms to 0ms relative to speech onset for word planning

Post-Utterance: 0ms to 250ms relative to speech onset for articulatory motor activity, and

Late: 400ms to 600ms relative to speech onset for feedback processing

At this point the unit of analysis was for each participant, for each electrode contact and for each epoch. Focusing on an epoch and electrode for a given participant, we then had two averages: one for the utterances corresponding to category and the other for the utterances corresponding to letter. We obtained an overall (two-sided) difference by taking the absolute value of the difference between these averages.

To get the reference distribution of the absolute difference we took all of the utterances in response to letters and all of utterances in response to categories. We randomly permuted the labels of all of these utterances thereby keeping the number of utterances of each stimulus type the same but changing which utterances corresponded to letters and which correspond to categories. We then, as with our original data, took the averages of letters and of categories, and we took the absolute value of this difference. This was done 10,000 times.

Finally, we obtained a p-value (this is for each of the four epochs, for each of the electrode contacts and for each of the seven participants) by identifying the fraction of the 10,000 permuted absolute values that lay above the absolute value that we computed from the actual data.

The result was thus for each participant to have a p-value for each epoch and for each electrode contact. Focusing on each epoch, we hence had 7 p-values for each channel. We used a false discovery rate (FDR) analysis to identify which channels are significant. The resulting 28 FDR analyses (one for each of the seven participants, one for each of the four epochs) are shown in Figure 6. The dots correspond to the electrodes that were found to be significant by this method. Even though the measure is two sided, we further distinguished the significant ones into those where the higher gamma activity is for letters (blue) and categories (red).

Figure 6:

Differences between letter and category verbal fluency across time.

Electrodes with significant difference (p<0.05 by two-tailed permutation testing across conditions, corrected by false discovery rate across electrodes) between letter and category conditions for each participant during selected timeframes: Early (850ms to 600ms prior to utterance onset), Pre-Utterance (250ms to 0ms prior to utterance onset), Post-Utterance (0ms to 250ms after utterance onset) and Late (400ms to 600ms after utterance onset). Timeframes selected to coincide with the following periods of language processing: cognitive search, word planning, articulation and feedback. Blue dots indicate contacts where high gamma activity for letter-motivated utterances exceeded that for category-motivated utterances, red dots indicate the inverse. P-values displayed for each participant reflect results of Cochran’s Q analysis. P-values less than 0.05 indicate significant changes across epochs in the number of electrodes with letter versus category differences. NP: Cochran’s Q test not performed due to insufficient number of electrode differences across epochs.

We then wanted to see whether the extent to which electrodes met criteria for significant difference between phonemic (letter) and semantic (category) conditions varied across the four epochs. Since the electrode contacts are the same across the 4 blocks (i.e. the data are paired), we used the Cochran’s Q test. We labeled each electrode within each epoch as YES or NO. We then calculated Cochran’s Q for every participant to determine whether electrode activation patterns were consistent over the 2-second period. Low p-values allow us to reject the null hypothesis that letter/category differences are relatively stable at the electrode level from epoch to epoch.

We also performed an analysis to estimate the extent to which different brain regions demonstrated changes in surface area recruitment over time with respect to speech onset. We grouped electrode contacts into the following regions: frontal (not including precentral), peri-Rolandic (precentral and postcentral), temporal, parietal (not including postcentral) and occipital. We determined the recruitment rates within each region as a ratio of number of active electrode contacts to total number of electrode contacts in each region and for each participant. To estimate the effect of epoch on recruitment rates for each region, we used ANOVA treating the participant as a random effect. Parameters were estimated in the traditional way using REML. We set the threshold for significance at p=0.05 for this analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and behavioral task performance

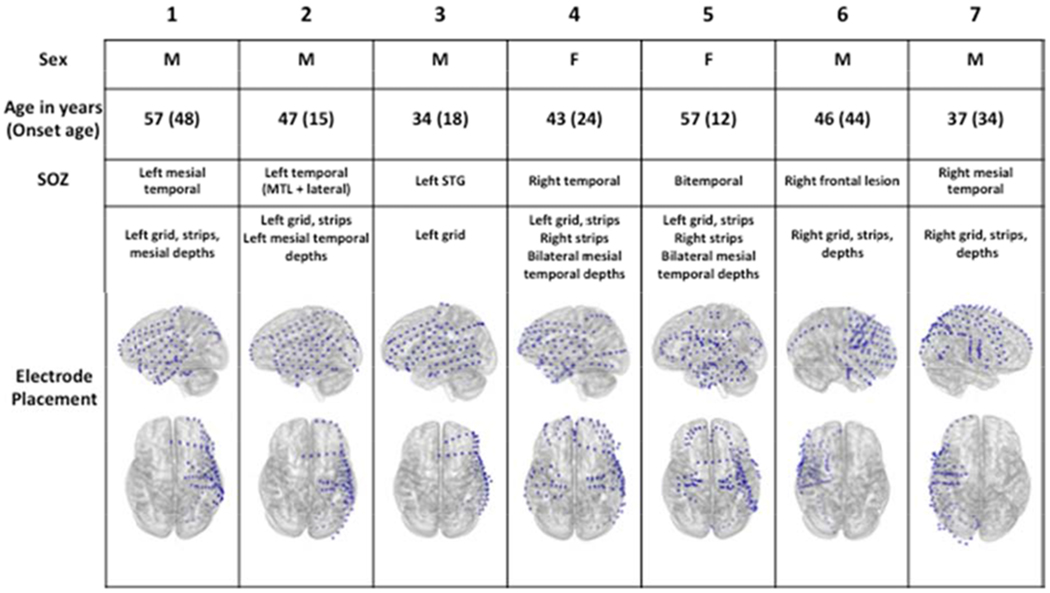

We recruited seven (7) patients for this study. Figure 2 summarizes clinical characteristics and electrode coverage maps. There were 5 left hemisphere-predominant implants and 2 right-predominant implants, with a median of 114 (range 80-122) electrode contacts per participant. All participants were right handed by self-report and left-hemisphere dominant for language (determined by stimulation mapping for participant 3, by Wada test for participants 2, 4, 5 and by fMRI for all other participants). There were 5 men and 2 women, and the median age was 46 years (range 34-57 years). Five of the participants had seizures recorded with mesial temporal onset (2 right, 2 left, 1 bilateral).

Figure 2:

Clinical characteristics and electrode placement.

Five left hemisphere-predominant implants (3 male, 2 female) and 2 right hemispheric implants (both male) were recorded. All participants were right handed by report and had onset of seizures after primary language development. Seizure onset zones are documented as identified during implant admission. Blue dots superimposed on grey brains indicate electrode localizations after coregistration of postoperative MRI with postoperative CT. MTL: mesial temporal lobe; SOZ: Seizure onset zone; STG: superior temporal gyrus.

Formal neuropsychological evaluations were available for all but participant 3. For the remainder, full scale IQ ranged from 80 to 100 (median 89) with verbal comprehension indices ranging from 87 to 107 (median 96). Verbal fluency testing using one of our categories (animals) and three of our selected letters (F, A, S) had previously been used during the preoperative neuropsychological testing. The test-retest latency ranged from 3 to 8 months (median 5 months).

Table 1 and Figure A.1 summarize behavioral task performance. In cases where participants ‘passed’ to end blocks earlier than 60 seconds, we considered there to be no additional exemplars for the remainder of the 60 second block. We thus took production rate (number of correct exemplars per block) as a measure of task performance. Out of 84 task blocks, 13 semantic and 10 phonemic blocks included pass responses, resulting in an average duration of 57.8 seconds per block.

Table 1.

Behavioral task performance

| 1 | 10.8 | 11.3 |

| 2 | 7.8 | 14.3 |

| 3 | 15.6 | 20.8 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 8.2 |

| 5 | 7.2 | 11.5 |

| 6 | 15.8 | 23.4 |

| 7 | 7.8 | 13.2 |

| Mean (SE) | 9.9(2.0) | 14.7(2.5) |

Mean production rate of correct exemplars uttered per 60-second block under category-based (semantic) and letter-based (phonemic) verbal fluency conditions. Participants underwent 6 blocks each of semantic verbal fluency, phonemic verbal fluency and rest (silent, cognitive function unconstrained) in variable order.

Overall, there was a broad range of performance with lower scores on phonemic (letter-cued) verbal fluency tasks (p = 0.002 by paired sample t-test). Patients with mesial temporal lobe involvement of their epilepsy tended to perform worse than those without mesial temporal involvement in both category-driven and letter-driven tasks. The two women in the study, the only participants with bilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, also appeared to perform worse than the men. The sample sizes of individual subgroups were too low to support formal statistical evaluation by sex, epilepsy type or laterality.

3.2. Spatiotemporal activation patterns associated with word utterances

Figures 3 and 4 depict mean (with 95% confidence intervals) high gamma activity patterns at selected electrodes in the letter-motivated and category-motivated conditions for participants 1 (left hemispheric recording) and 6 (right hemispheric recording), respectively. Activity exceeding the t =1.96 threshold relative to resting baseline is identified by colored bars across the top of each graph. Trial-level raster plots are provided in Figures A.2 and A.3. Regions of elevated high gamma activity at specific time intervals are shown for all participants individually in Figure A.4. Dynamic videos of the pooled activation maps are also provided in Appendix B.

A median 16% of electrode contacts showed no significant difference in high gamma activity from resting baseline. Among those that did show task-related fluctuations, we noted four principal patterns of activation common across participants. Early (more than 750ms prior to speech onset) suprathreshold activity was present in bilateral prefrontal regions, but also in right inferior frontal and right temporal regions specifically during category motivated search. In left hemispheric contacts, this activity diminished to subthreshold levels prior to speech onset but remained qualitatively high with respect to resting activity (see Figure 3, panels A-C).

In a subgroup of electrode contacts there was high gamma activity that rose to suprathreshold levels between 600ms prior to speech onset and 100ms after onset. This pattern occurred in distributed areas of left inferior frontal, orbitofrontal and temporal cortex, in keeping with prior models of word planning processes (lexical selection, phonological planning, syllabification). The electrodes that demonstrated this activity for letter fluency overlapped but were not exactly congruent with those demonstrating the same activity patterns for category fluency (see Figure 4).

Several electrodes in peri-Rolandic sensorimotor cortex demonstrated high gamma activity that reached suprathreshold levels less than 100ms prior to speech onset and peaked within 300ms after onset. This pattern is consistent with oromotor activation at the time of speech onset and is similar to observations in prior studies of overt reading, picture naming and verb generation tasks (Brumberg et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2010). It was observed in both right and left hemispheric implants. Interestingly, in the right hemispheric implants a subset of peri-Rolandic electrodes demonstrated suprathreshold activity even at the early pre-utterance timepoints (i.e. 750ms or more prior to speech onset) for category fluency.

By contrast to prefrontal and peri-Rolandic electrodes, contacts over the posterior temporal and inferior parietal regions showed subthreshold activity in the pre-utterance period. After speech onset, activity in these regions rose dramatically to peak at 300-400ms post utterance. This pattern has also been observed in prior studies of speech production and may reflect auditory feedback processing in response to the participants’ own speech (Brumberg et al., 2016; Cervenka et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2010).

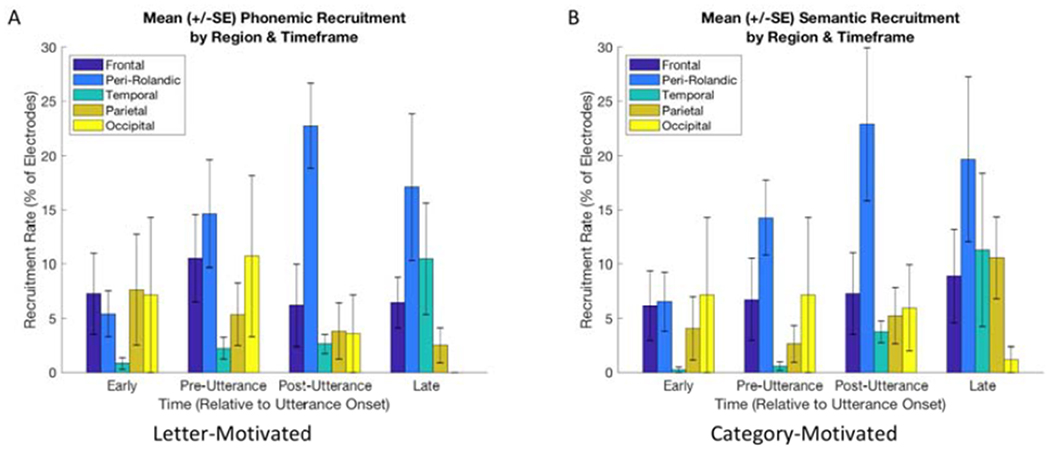

Figure 5 summarizes electrode contact recruitment rates (percentage of contacts reaching threshold) in each major region as a function of time relative to speech onset. For both letter-motivated and category-motivated conditions, frontal recruitment rates remained relatively stable over time. Recruitment rates in the peri-Rolandic regions increased near the time of utterance onset and this change across epochs was statistically significant (p = 0.008 in the letter-motivated condition, p = 0.014 in the category-motivated condition). The temporal lobe recruitment rate tended to increase in the late post-utterance period, although this change across epochs reached statistical significance only in the letter-motivated condition (p = 0.047 versus p = 0.131 in the category-motivated condition).

Figure 5:

Electrode contact recruitment rates by region and timeframe.

Mean (+/− standard error) percentage of electrode contacts with task-related activation in the frontal (not including precentral), peri-Rolandic, temporal, parietal (not including postcentral) and occipital regions at early (600-850ms prior), pre-utterance (0-250ms prior), post-utterance (0-250ms after) and late (400-600ms after) timeframes for letter-motivated and category-motivated utterances. SE: standard error.

3.3. Comparison of activation patterns for category- and letter-motivated utterances

We used permutation testing to identify electrodes demonstrating significant differences in high gamma activity between letter and category conditions at specified epochs with respect to speech onset. Figure 6 illustrates electrodes meeting criteria for statistical significance at p<0.05, corrected for multiplicity. Differences across epochs were observed for 4 of the 7 participants. In participants 1-3, letter-motivated exemplars tended to elicit a more robust response than category-motivated exemplars in the regions sampled (mean 16.5% of electrodes with increased activity for letter fluency in the epochs examined, compared with 4.4% of those with increased activity for category fluency, p = 0.069). This was most prominent in the immediate pre-utterance timeframe (0-250ms prior to utterance onset), involving 66% of all differentially active electrodes for these participants. Participants 4, 5 and 7 demonstrated sparse differences in the regions sampled. Participant 6, who was the only participant without temporal lobe involvement of his epilepsy, demonstrated robust increases for category fluency throughout the regions sampled in all timeframes except immediately post-utterance (5.7% of electrodes with significant difference during this epoch by comparison to mean 38.3% with significant differences for other epochs; p < 10−10 across epochs by Cochran’s Q, corrected for multiple comparisons). Of note, participants 3 and 6, whose epileptic networks were limited to neocortical regions, demonstrated the largest percentage of cortical regions with significant differences between letter-based and category-based fluency (mean 45.3% of electrodes demonstrating differences for these two participants, compared to 7% of participants with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy), however limited group size precludes formal statistical comparison.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that overt, self-paced verbal fluency tasks can be successfully performed and evaluated using intracranial electroencephalography. Although several language paradigms have been implemented using iEEG, ours is the first study to investigate the high-resolution spatiotemporal activation patterns associated with spontaneous utterances in a free recall paradigm. Though the number of participants in this study is small, our findings complement existing verbal fluency literature, which aggregates neurophysiologic signals over several seconds at a time. Our observations have implications for current models of language production, and potentially for invasive strategies to improve language function in patients with focal lesions such as due to stroke or traumatic injury. Below we interpret our findings, breaking them down based on timeframes previously associated with specific elements of the speech production process, and offer a possible explanatory model for how words are produced in the context of verbal fluency paradigms.

4.1. Spatial and temporal dynamics of spontaneous utterances

4.1.1. Cognitive search and lexical retrieval timeframe

As previously discussed, verbal fluency tasks differ from other language production tasks in that the prerequisite conceptual preparation step depends on a concurrent memory search for acceptable exemplars. Studies of picture naming and verb generation suggest that subsequent sub-processes involved in word production (e.g. lexical selection, articulatory preparation) occur over the 600ms prior to speech onset (Indefrey, 2011; Llorens et al., 2011). To investigate the neurophysiologic activation patterns associated with cognitive search, we thus examined the time period earlier than 600ms prior to speech onset, positing that during this timeframe, participants are actively engaged in cognitive search without significantly involving canonical lemma selection or articulation processes.

During this timeframe, we observed gamma activation in the superior and middle frontal regions across participants on both category and letter fluency tasks (Figures 3, 4 and A.4). In letter fluency, this activity was seen predominantly in left hemispheric implants, whereas category fluency elicited ‘search’ timeframe activation in the right hemisphere as well. Our findings are consistent with fMRI studies of verbal fluency tasks demonstrating increased blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) activity in prefrontal cortex during these paradigms compared to rest or rote recitation (Abrahams et al., 2003; Birn et al., 2010; Li et al., 2017). By contrast, we did not see consistent involvement of the left inferior frontal gyrus across participants, as is reported in fMRI and PET literature on phonemic verbal fluency. While this may be partly due to incomplete electrode coverage in this region for some participants, varying functional network architecture across individuals may also contribute. This may be of particular significance in individuals with epilepsy, who are expected to have variation in functional and anatomic localization due to aberrant plasticity as a result of epileptiform activity, or the underlying cause of their seizures (Gaillard et al., 2008). Of note, however, none of our participants had seizure onset zones in the left frontal region.

Many of the areas active during the cognitive search timeframe showed a subtle decrease in average high gamma activity 200-300ms prior to speech onset, but in many trials continued activity during the remaining peri-utterance timeframe (Figure A.2). This may signify that networks involved in conceptual search occasionally continue their function even while suitable exemplars are identified and speech production processes are launched in parallel. An alternative explanation is that the lexical search and speech production processes engage overlapping anatomical regions. Although the latter explanation seems less likely given that tasks involving only the latter processes (e.g. auditory word repetition or reciting well-known lists) do not typically result in extensive prefrontal activation (Behroozmand et al., 2015; Bookheimer, Zeffiro, Blaxton, Gaillard, & Theodore, 2000), it is supported by the fact that in category fluency, a subset of the ‘search’-active electrodes in our study demonstrated further increases in activity during later timeframes with respect to speech onset. A prior study of high gamma activity patterns in picture naming suggests relatively little temporal overlap among regions responsible for early word production processes (Dubarry et al., 2017). Indeed, examination of our trial level data for individual electrodes suggests that in a subset of trials the prefrontal activity persisted well into the post-utterance phase. Trial by trial comparison of the duration of prefrontal activity with subsequent interutterance latency may provide some insight to the dynamics of this process, but is outside the scope of the current investigation. Taken together, our findings suggest that conceptual search processes employ prefrontal activation, and that these processes may continue in parallel with subsequent word planning and speech production processes.

4.1.2. Lexical selection and phonological encoding timeframe

Left hemispheric implants showed focal increases in high gamma activity that peaked less than 600ms prior to speech onset with a decline before or during articulation. These peaks occurred in distributed areas including left inferior frontal, middle frontal, inferior parietal and posterior temporal regions. Prior studies of word generation suggest that word planning (lexical selection, phonological and phonemic encoding) occurs during this timeframe, i.e. 200-400ms post-stimulus, assuming an average response latency of 600ms (Indefrey, 2011). Our observations are consistent with this model, and additionally suggest involvement of the middle frontal gyrus (MFG) in some participants (e.g. our participant 1, see Figure A.4). Assuming a semantic network architecture is invoked during verbal fluency task execution (Gaskell & Marslen-Wilson, 1999; Troyer & Moscovitch, 2006), one might ascribe the MFG activation to lexical selection processes occurring during this timeframe. However, the MFG activity demonstrated by our participants was notably more robust in the letter-motivated condition, wherein selection among competing potential exemplars with similar or overlapping meanings is unlikely to be a major component. A previous study found high gamma perturbations in the left MFG during word production tasks with visual stimuli and concluded that this region serves as a temporal perceptual information storage space (Wen et al., 2017). A prior investigation of spatial and temporal dynamics of semantic priming and interference effects found evidence for involvement of a widespread network, including the MFG and other parts of the lateral PFC, medial PFC and lateral premotor cortex during this timeframe (S. K. Riès et al., 2017). We thus propose that in this case the MFG also participates in the lexical selection subtask. Ideally a comparison to a task that isolates these sub-processes within the same participant would shed light on this picture, however real time signal analysis to identify such needs was not available at the time of our recording.

Interestingly, the regions active during presumed word planning timeframes for letter fluency overlapped partly but not completely with those active for category fluency. We learn from this that the implementation of the two tasks may differ not only in the search mechanisms, but perhaps also in the cortical areas involved in word planning and production. Further studies with larger numbers of participants and dedicated task paradigms would be useful to clarify this unintuitive implication.

4.1.3. Articulatory planning and execution timeframe

Starting at 200-300ms prior to utterance onset, we observed increases in high gamma activity in spatially precise but distributed areas of peri-Rolandic cortices. This activity was seen in both right and left implants and likely represents articulatory planning and motor activation. These findings are remarkably consistent with those observed in overt picture naming and verb-generation paradigms, as well as during syllable production (Bouchard, Mesgarani, Johnson, & Chang, 2013; Edwards et al., 2010).

Interestingly, participant 7 demonstrated a parallel pattern of activation in the temporo-parietal-occipital (TPO) junction, consistent with prior observations suggesting a ‘subsystem’ within Wernicke’s area engaged in the motor act of speech in some people (Blank, 2002; Edwards et al., 2010; Wise et al., 2001).

4.1.4. Feedback processing timeframe

In the post-utterance timeframe, we consistently observed dramatic high gamma activity increase in the posterior temporal and inferior parietal regions. This activity was seen bilaterally. Similar patterns have been observed in picture naming, word repetition, word reading and verb generationtasks, and have been suggested to be a form of self-monitoring (Crone, Hao, et al., 2001; Edwards et al., 2010). Using fMRI, Birn and colleagues (Birn et al., 2010) saw decreased activity in the posterior superior temporal regions during verbal fluency compared to an automatic speech task, suggesting that activity in this region is not a primary auditory phenomenon. Our observations may represent a correlate to the N400 event-related potential that typically occurs when people listen to natural speech, words and sentences (Kutas & Federmeier, 2011; Marinkovic et al., 2003). We propose that posterior temporal activation in this context represents a combination of auditory feedback and semantic processing, noting that in several electrodes there is a difference between levels of activation induced by phonemic versus semantic stimuli. Such a hypothesis could be further evaluated with a dedicated task evaluating post-utterance activation compared with activation patterns during passive listening to words or hearing unexpected noises for individual participants.

4.1.5. Comparison to other word processing tasks

Several of our findings are similar to what one might observe in traditional stimulus-locked word production tasks previously reported in the literature. Response-locked analyses of word production do offer different insights to the spatiotemporal dynamics than stimulus-locked analyses (S. Riès, Janssen, Burle, & Alario, 2013). To disambiguate this effect, we undertook an ad hoc analysis of a pilot repetition task that participant 1 undertook during the same study session as his verbal fluency task (Figure A.5). In contrast to the early prefrontal high gamma seen during the putative cognitive search timeframe in verbal fluency, the prefrontal high gamma did not surpass resting levels until 700ms or less prior to utterance onset. The distributed activity observed in the word planning timeframe during verbal fluency was only sporadic or largely absent during the repetition task. Perirolandic and posterior superior temporal activity during the articulatory planning and auditory feedback timeframes was conserved during the repetition task, with additional preutterance activation in the temporal regions likely attributable to auditory processing of the stimulus. These patterns are consistent with prior investigations of word repetition (Crone, Hao, et al., 2001; Pei et al., 2011) and suggest that the distinctions in our observations of patterns in verbal fluency are not solely attributable to the use of response-locked analyses.

4.2. Category-motivated versus letter-motivated verbal fluency

We expected the earliest time period (more than 600ms prior to utterance onset) to demonstrate the most robust differences between semantic and phonemic verbal fluency because these two conditions require slightly different search strategies but presumably similar lexical selection and speech production processes (Troyer & Moscovitch, 2006). Surprisingly, we found statistically significant differences across the peri-utterance timeframe. The epoch demonstrating the most widespread areas of differential activation across participants was immediately pre-utterance (less than 250ms prior to speech onset). This suggests that speech production processes specific to letter- or category-motivated verbal fluency occur most robustly in the period immediately prior to speech onset, or they are more differentially “jittered” with respect to speech onset. The latter explanation would be expected given that letter and category fluency tasks differ in level of difficulty, as a whole and as a function of the specific letter or category stimuli used. On the other hand, examples of processes that may be condition-specific and occur in this timeframe include pre-speech self-monitoring (e.g., internal self-monitoring, performing a last minute ‘check’ to validate that an exemplar to be uttered fits the stimulus criteria) or late parallel conceptual activation (e.g. invoking a word meaning in response to an orthographically or phonemically-driven lexical selection process). Further studies with larger datasets may shed light on these processes by examining the semantic and linguistic properties of exemplars associated with differential activation in the late pre-utterance timeframe.

Participant 6 was the only person to demonstrate widespread increases in semantic verbal fluency across nearly all regions sampled. These were present during search, pre-utterance and late timeframes, but were less prominent during the immediate post-utterance epoch. In the late post-utterance timeframe (more than 250ms after utterance onset) the same participant also had widespread increases in response to category-motivated stimuli. This pattern was very different from those observed in other participants. The relatively high performance in this task, as well as an epileptic network far removed from more classically localized language-generating regions, argue that this participant may represent a normal variant pattern. His network might also represent a different cognitive strategy for completing the verbal test, for example relying more heavily on visualization during category-cued verbal fluency and/or self-monitoring of language output. Interestingly, the two patients with the highest performance in both letter and category fluency demonstrated the most widespread areas of difference between category and letter fluency. These also were the two patients without evidence of mesial temporal involvement in their seizures. Although the sample sizes are too small for formal statistics, this does beg the question of whether specialization contributes to performance and whether mesial temporal lobe epilepsy undermines this specialization, e.g. because of epilepsy-related plasticity or because of impaired memory retrieval due to mesial temporal dysfunction. The caveat is that electrodes were placed according to clinical necessity, so we were able to record only two right hemisphere implants. It is thus impossible to assess the activity of the alternate hemisphere for these patients. Our lack of findings for the patients with lower performance could have been because all of their significant differences were in the contralateral hemisphere.

Overall, the variety of patterns of significant differences between conditions is surprising in the context of the existing verbal fluency literature. This variety was made apparent because of the decision to pursue statistical analyses at an individual participant level and highlights the role of random variance in biomedical research. Specifically in the context of our investigation, it suggests that although regional differences can be observed between letter and category fluency at the group level (Birn et al., 2010; Paulesu et al., 2016), differential performance on these two tasks may not be as easily attributable to a specific region in an individual patient.

4.3. Potential contribution of the medial temporal region

The task employed in this study is fundamentally a free recall paradigm, and as such one might expect prominent activation of the medial temporal lobe. We did not see evidence of such activation in most participants. We noted, however, that the two highest performing participants did not have mesial temporal involvement of their epilepsy, and of these the one participant that had mesial temporal recordings did show significant activation of the mesial temporal region on task compared to rest. An additional participant was recorded with a similar paradigm but fewer stimuli and also demonstrated increased high gamma activity (see Figure A.6) in the hemisphere contralateral to the seizure onset zone.

Ad hoc analysis showed that this activity did not vary substantially between conditions (category versus letter motivated), but that the increase in high gamma activity was largely driven by speaking (as opposed to silent) periods of the recording. Other studies have also implicated hippocampal complex in language production tasks (Covington & Duff, 2016; Gleissner & Elger, 2001; Hamamé, Alario, Llorens, Liégeois-Chauvel, & Trébuchon-Da Fonseca, 2014; Piai et al., 2016; Troyer & Moscovitch, 2006). Most of these studies point to a role of the hippocampus in working memory necessary for maintaining contextual information for communication. Our observations, as well as those by Gleissner and Elger (Gleissner & Elger, 2001), suggest that in some people the hippocampus contributes to word production independent of language context, and that inability to mount a functional gamma activity may underlie the impaired memory performance in epilepsy patients.

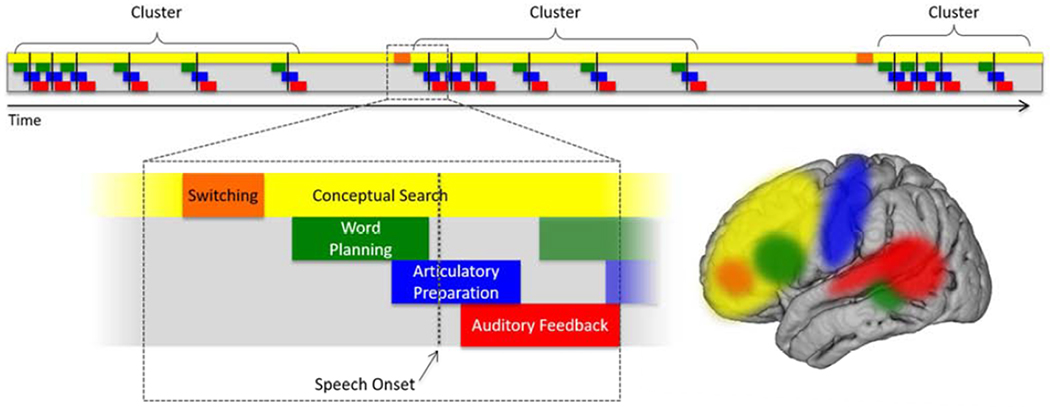

4.4. Toward a model of verbal fluency

Interpreted in the context of prior studies (Birn et al., 2010; Collard et al., 2016; Indefrey, 2011; Sheldon & Moscovitch, 2012; Troyer et al., 1997), we suggest a framework for understanding neurophysiologic processes underlying execution of the verbal fluency task (Figure 7). We propose that cognitive search processes may occur nearly consistently throughout the task and employ distributed regions, most commonly prefrontal cortex. Phonemic (letter-motivated) and semantic (category-motivated) search may employ overlapping, but not entirely equivalent networks that vary across individuals. When a suitable exemplar is identified, word planning processes occur by way of (possibly coordinated) activation of a distributed network including prefrontal cortex and superior temporal sulcus. This is followed by articulatory preparation, utilizing peri-Rolandic sensorimotor cortices bilaterally. Subsequent speech onset triggers auditory feedback processes in the posterior temporal and inferior parietal regions. We propose that lexical selection, articulatory preparation and auditory feedback may occur in parallel with ongoing search activity in the prefrontal cortex, enabling identification and articulation of several exemplars in rapid succession. Importantly, prior studies of verbal fluency also recognized a periodic switch in search strategies that is postulated to dependend on frontal regions (Laisney et al., 2009; Troyer et al., 1997) although the precise localization (if one exists across individuals) is yet to be determined. This was not investigated in our study but should be considered in any model of verbal fluency.

Figure 7:

Proposed model for verbal fluency.

Conceptual search processes occur on an ongoing basis and employ distributed areas including prefrontal cortex. Specific (but as yet undefined) frontal regions are likely involved in switching among subcategories for a given criterion/stimulus. Word planning may involve coordinated activity of prefrontal, inferior frontal, temporal and inferior parietal regions. Articulatory preparation occurs primarily in peri-Rolandic sensorimotor cortex. After speech onset, auditory feedback processing employs posterior superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal regions. We propose that cognitive search processes are ongoing in parallel with lexical selection and speech production processes.

Our proposed model has several limitations and will most certainly be subject to revision as more is learned about the various sub-processes referenced above. For example, we have limited the model to lateral neocortical activation patterns most commonly sampled in our population, and the impact of deeper structures (hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, insula, medial PFC, pre-supplementary motor cortex etc.) is not addressed. Further, the question of whether lemma selection from a variety of competing concepts applies in both semantic and phonemic verbal fluency conditions has not been answered. Additionally, the timing and localization of the switching phenomenon and the degree to which the various subprocessing steps overlap temporally (if at all) on a trial-by-trial basis are yet to be elucidated. Nonetheless, our hope is to provide a framework for further discussion and refinement. Understanding the neurophysiologic activity patterns contributing to verbal fluency will improve our interpretation of performance deficits seen in a spectrum of neurocognitive disorders affecting language and memory, and may offer new insights to potential therapeutic strategies.

4.5. Implications for invasive strategies to improve language function

Although currently envisioned devices for speech prostheses focus on enhancing function at the peripheral nerve and muscle coordination level, technology is being developed to replace or enhance cognitive functions related to memory and language production as well. These devices may address dysfunction in memory encoding and retrieval, lexical retrieval as well as phonological encoding and syllabification. They could be helpful, for example, in patients with post-stroke or post-traumatic aphasia. Our findings suggest that successful implanted devices will require flexibility in their architecture, at both a hardware and software level, and will need to be take on a form that allows for spatially distributed sampling.

5. Limitations

We studied spatiotemporal dynamics associated with verbal fluency in a small, consecutive, non-selected sample of patients. The size of our cohort, variable sampling of language networks (due to clinical necessity) and heterogeneity of brain pathology in our participants are all limitations of this study. Prior studies demonstrate heterogeneity in functional language networks even among healthy normal individuals (Billingsley et al., 2004; Kahlaoui et al., 2012), and as a function of age and task conditions (Brickman et al., 2005) and it makes sense that at least the same variability would be expected among patients with medically refractory epilepsy (Gaillard et al., 2008). Additionally, spatial sampling in studies like ours is limited to structures where electrodes are implanted out of clinical necessity, which renders cross-subject comparisons difficult. Nonetheless, there are common themes that provide useful insight to the temporal dynamics of verbal fluency, such as early prefrontal activation, sensorimotor involvement in articulatory preparation and post-response temporoparietal activation. Further analyses using larger groups of patients may better explain our observations, place boundaries on the degree of individual variability in network architecture, and may even elucidate the differential effects of various types of epilepsy. Though electrocorticography experiments do not allow for a comparison to the general population, studies across a variety of seizure onset zone locations and underlying etiologies can improve signal to noise ratio and give insight to probable mechanistic inferences. Additionally, modalities such as magnetoencephalography (MEG) may be of great utility here, provided that the brain regions to be sampled are close to the cortical surface and thus to MEG sensors. In these cases, comparison of patients with epilepsy and healthy normal controls, using similar language tasks, may be feasible.

Another contributor to noise in the spatiotemporal maps of this study is variability in timing across utterances. Changes in level of alertness or task engagement are known to affect variability and latency of reaction times (Appelle & Oswald, 1974). In this study, we interpret our findings assuming the same overall timing of cognitive subprocesses related to word production for each individual, using prior findings in healthy normal participants as a guide. However other studies utilizing high gamma activity have observed different reaction times across individuals and explored timing of activation patterns as a function of each individual’s average reaction time (Edwards et al., 2010; S. Riès et al., 2013). The free recall format of our paradigm limits our ability to formally assess a specific reaction time per se, although notably certain patterns of activation (e.g. post-response temporoparietal activity) appear relatively invariant. Nonetheless, it may be advantageous in future studies using similar formats to establish a baseline ‘standard’ average reaction time and ‘normalize’ temporal patterns to that standard for each individual.

We did not systematically analyze differences across individual letters or categories. Wang and colleagues (Wang, Degenhart, Sudre, Pomerleau, & Tyler-Kabara, 2011) showed different electrocorticographic patterns in frequency and time domains for different categories in a picture naming task and it is reasonable to expect such differences in category-based verbal fluency. This could be the subject of a further subanalysis, however it would likely be more successful with a larger number of participants and possibly with repeated stimuli.

Several prior studies evaluating neurophysiologic signatures of verbal fluency utilize an automatic speech condition for comparison (Birn et al., 2010; Schlösser et al., 1998). This technique could have provided more insight into the distinction between prefrontal search activity and the lexical selection subprocess. Further studies may be strengthened by including this third condition, as well as passive listening words, non-words and unexpected sounds to further dissect the auditory feedback processing activity in the posterior superior temporal region. Including these tasks was, however, outside the scope of the current study.

We make no assumptions regarding the contribution of clustering versus switching to the early prefrontal activation we observed. Given that we discarded utterances that were produced too closely together to be evaluated independently, our observations could represent predominantly search within a cluster or switching between clusters. To our knowledge there are currently no published studies investigating the timing of switching activities with regard to word clusters. We propose that a paradigm similar to the current study may provide an opportunity to clarify this.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we used high gamma activity on intracranial EEG to characterize the neuronal activation patterns associated with speech production in an overt, self-paced, letter- and category-motivated verbal fluency paradigm. The use of high gamma activity allows us to characterize human cognition with temporal resolution that exceeds functional MRI or PET, with good spatial resolution. Our approach differs from other iEEG studies in the nature of the language paradigm and in the self-paced nature of the task.

We observed high gamma increases in distributed prefrontal regions during the putative cognitive search timeframe, robust sensorimotor cortex increases during articulatory preparation and post-utterance temporoparietal activation consistent with auditory feedback processing. Our observations extend prior studies of stimulus-locked word generation with investigation of neuronal activation patterns associated with cognitive search. Variability in the differences between letter- and category-motivated verbal fluency likely reflects inter-individual heterogeneity in search strategies and conceptual representations. The underlying epileptic networks are almost certain to play a role and should not be ignored. Based on this work and others, we propose a model for the functional neuroanatomy of the verbal fluency task. We hope to thus contribute to the general understanding of this widely used but as yet incompletely understood neuropsychological evaluation tool.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

We recorded electrocorticography during overt responses in a verbal fluency task.

Left frontal regions activate during letter-motivated search.

Bifrontal regions activate during category-motivated search.

A distributed network over the left hemisphere activates during word planning.

Peri-Rolandic and posterior temporal regions activate with and after articulation.

7. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant numbers NS091006 (PI: Brian Litt), NS080565 (PI: Frances Jensen), and NS099348 (PI: Brian Litt); and by the Mirowski Family Foundation through the University of Pennsylvania Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics. These funding sources had no participation in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors would like to thank Dr. Jensen for her support and mentorship, Jacqueline Boccanfuso for her help in IRB preparation and data conversion, as well as Drs. Gerwin Schalk and Kathryn Davis for their advice and encouragement.

Footnotes

Present address: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 1161 21st Ave. South, MCN A0116, Nashville, TN 37232

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none.

Data statement: The raw data for this publication are available online at ieeg.org.

References

- Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, Simmons A, Brammer MJ, Williams SCR, Giampietro VP, … Leigh PN (2003). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of verbal fluency and confrontation naming using compressed image acquisition to permit overt responses. Human Brain Mapping, 20(1), 29–40. 10.1002/hbm.10126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreou G, & Trott K (2013). Verbal fluency in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 5(4), 343–351. 10.1007/s12402-013-0112-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelle S, & Oswald LE (1974). Simple Reaction Time as a Function of Alertness and Prior Mental Activity. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 55(3_suppl), 1263–1268. 10.2466/pms.1974.38.3c.1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo N. B. de, Barca ML, Engedal K, Coutinho ESF, Deslandes AC, & Laks J (2011). Verbal fluency in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and major depression. Clinics, 66(4), 623–627. 10.1590/s1807-59322011000400017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behroozmand R, Shebek R, Hansen DR, Oya H, Robin DA, Howard MA, & Greenlee JDW (2015). Sensory-motor networks involved in speech production and motor control: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 109, 418–428. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley RL, Simos PG, Castillo EM, Sarkari S, Breier JI, Pataraia E, … Breier JI (2004). Spatio-Temporal Cortical Dynamics of Phonemic and Semantic Fluency. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 26(8), 1031–1043. 10.1080/13803390490515333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Kenworthy L, Case L, Caravella R, Jones TB, Bandettini PA, & Martin A (2010). Neural systems supporting lexical search guided by letter and semantic category cues: A self-paced overt response fMRI study of verbal fluency. NeuroImage, 49(1), 1099–1107. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank SC (2002). Speech production: Wernicke, Broca and beyond. Brain, 125(8), 1829–1838. 10.1093/brain/awf191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ, Giordani B, Berent S, Amato DA, Lehtinen S, Koeppe RA, … Kuhl DE (1992). Verbal Fluency and Positron Emission Tomographic Mapping of Regional Cerebral Glucose Metabolism. Cortex, 28(2), 231–239. 10.1016/S0010-9452(13)80051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY, Zeffiro TA, Blaxton TA, Gaillard W, & Theodore WH (2000). Activation of language cortex with automatic speech tasks. Neurology, 55(8), 1151–1157. 10.1212/WNL.55.8.1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard KE, Mesgarani N, Johnson K, & Chang EF (2013). Functional organization of human sensorimotor cortex for speech articulation. Nature, 495(7441), 327–332. 10.1038/nature11911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Williams LM, MacGregor KL, Jefferson AL, … Gordon E. (2005). Category and letter verbal fluency across the adult lifespan: Relationship to EEG theta power. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 20(5), 561–573. 10.1016/j.acn.2004.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg JS, Krusienski DJ, Chakrabarti S, Gunduz A, Brunner P, Ritaccio AL, & Schalk G (2016). Spatio-temporal progression of cortical activity related to continuous overt and covert speech production in a reading task. PLoS ONE, 11(11). 10.1371/journal.pone.0166872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervenka MC, Corines J, Boatman-Reich DF, Eloyan A, Sheng X, Franaszczuk PJ, & Crone NE (2013). Electrocorticographic functional mapping identifies human cortex critical for auditory and visual naming. NeuroImage, 69, 267–276. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collard MJ, Fifer MS, Benz HL, McMullen DP, Wang Y, Milsap GW, … Crone NE. (2016). Cortical subnetwork dynamics during human language tasks. NeuroImage, 135, 261–272. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.03.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington NV, & Duff MC (2016, December 1). Expanding the Language Network: Direct Contributions from the Hippocampus. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Elsevier Ltd; 10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Boatman D, Gordon B, & Hao L (2001). Induced electrocorticographic gamma activity during auditory perception. Brazier Award-winning article, 2001. Clinical Neurophysiology: Official Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(4), 565–582. 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00545-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Hao L, Hart J, Boatman D, Lesser RP, Irizarry R, & Gordon B (2001). Electrocorticographic gamma activity during word production in spoken and sign language. Neurology, 57(11), 2045–2053. 10.1212/WNL.57.11.2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubarry AS, Llorens A, Trébuchon A, Carron R, Liégeois-Chauvel C, Bénar CG, & Alario FX (2017). Estimating Parallel Processing in a Language Task Using Single-Trial Intracerebral Electroencephalography. Psychological Science, 28(4), 414–426. 10.1177/0956797616681296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E, Nagarajan SS, Dalal SS, Canolty RT, Kirsch HE, Barbaro NM, & Knight RT (2010). Spatiotemporal imaging of cortical activation during verb generation and picture naming. NeuroImage, 50(1), 291–301. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlis AC, Herrmann MJ, Plichta MM, & Fallgatter AJ (2007). Cortical activation during two verbal fluency tasks in schizophrenic patients and healthy controls as assessed by multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy. Psychiatry Research - Neuroimaging, 156(1), 1–13. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.1L007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard W, Berl M, Moore E, Ritzl EK, Rosenberger L, & Theodore WH (2008). Atypical language in lesional and nonlesional complex partial epilepsy. Neurology, 70(23), 1761–1771. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316841.43348.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell MG, & Marslen-Wilson WD (1999). Ambiguity, competition, and blending in spoken word recognition. Cognitive Science, 23(4), 439–462. 10.1207/s15516709cog2304_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleissner U, & Elger C (2001). The hippocampal contribution to verbal fluency in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Cortex, 37, 55–63. 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70557-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glikmann-Johnston Y, Oren N, Hendler T, & Shapira-Lichter I (2015). Distinct functional connectivity of the hippocampus during semantic and phonemic fluency. Neuropsychologia, 69, 39–49. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamé CM, Alario FX, Llorens A, Liégeois-Chauvel C, & Trébuchon-Da Fonseca A (2014). High frequency gamma activity in the left hippocampus predicts visual object naming performance. Brain and Language. 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim S, Eickhoff SB, Ischebeck AK, Friederici AD, Stephan KE, & Amunts K (2009). Effective connectivity of the left BA 44, BA 45, and inferior temporal gyrus during lexical and phonological decisions identified with DCM. Human Brain Mapping, 30(2), 392–402. 10.1002/hbm.20512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henin S, Shankar A, Hasulak N, Friedman D, Dugan P, Melloni L, … Liu A (2019). Hippocampal gamma predicts associative memory performance as measured by acute and chronic intracranial EEG. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 9: 593 10.1038/s41598-018-37561-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshorn EA, & Thompson-Schill SL (2006). Role of the left inferior frontal gyrus in covert word retrieval: Neural correlates of switching during verbal fluency. Neuropsychologia, 44(12), 2547–2557. 10.1016/INEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2006.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indefrey P (2011). The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components: A critical update. Frontiers in Psychology. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, & Smith SM (2012). FSL.Neuroimage, 62(2), 782–790. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlaoui K, Sante G. Di, Barbeau J, Maheux M, Lesage F, Ska B, & Joanette Y. (2012). Contribution of NIRS to the study of prefrontal cortex for verbal fluency in aging. Brain and Language, 121(2), 164–173. 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, & Federmeier KD (2011). Thirty Years and Counting: Finding Meaning in the N400 Component of the Event-Related Brain Potential (ERP). Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 621–647. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisney M, Matuszewski V, Mézenge F, Belliard S, De La Sayette V, Eustache F, & Desgranges B (2009). The underlying mechanisms of verbal fluency deficit in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Journal of Neurology, 256(7), 1083–1094. 10.1007/s00415-009-5073-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li P, Yang QX, Eslinger PJ, Sica CT, & Karunanayaka P (2017). Lexical-Semantic Search Under Different Covert Verbal Fluency Tasks: An fMRI Study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 11 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorens A, Trébuchon A, Liégeois-Chauvel C, & Alario FX (2011). Intra-cranial recordings of brain activity during language production. Frontiers in Psychology. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovic K, Dhond RP, Dale AM, Glessner M, Carr V, & Halgren E (2003). Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Modality-Specific and Supramodal Word Processing. Neuron, 35(3), 487–497. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00197-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metternich B, Buschmann F, Wagner K, Schulze-Bonhage A, & Kriston L (2014). Verbal fluency in focal epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis Neuropsychology Review. Springer New York LLC; 10.1007/s11065-014-9255-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourski KV, Steinschneider M, Oya H, Kawasaki H, Jones RD, & Howard MA (2014). Spectral organization of the human lateral superior temporal gyrus revealed by intracranial recordings. Cerebral Cortex, 24(2), 340–352. 10.1093/cercor/bhs314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourski KV, Steinschneider M, Rhone AE, & Howard III MA (2017). Intracranial Electrophysiology of Auditory Selective Attention Associated with Speech Classification Tasks. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks RW, Loewenstein DA, Dodrill KL, Barker WW, Yoshii F, Chang JY, … Duara R (1988). Cerebral metabolic effects of a verbal fluency test: A PET scan study. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 10(5), 565–575. 10.1080/01688638808402795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Goldacre B, Scifo P, Cappa SF, Gilardi MC, Castiglioni I, … Ca FF. (2016). Functional heterogeneity of left inferior frontal cortex as revealed by fMRI, 5(8), 2011–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei X, Leuthardt EC, Gaona CM, Brunner P, Wolpaw JR, & Schalk G (2011). Spatiotemporal dynamics of electrocorticographic high gamma activity during overt and covert word repetition. Neuroimage, 54(4), 2960–2972. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piai V, Anderson KL, Lin JJ, Dewar C, Parvizi J, Dronkers NF, & Knight RT (2016). Direct brain recordings reveal hippocampal rhythm underpinnings of language processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(40), 11366–11371. 10.1073/PNAS.1603312113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riès S, Janssen N, Burle B, & Alario F-X (2013). Response-Locked Brain Dynamics of Word Production. PLoS ONE, 5(3), e58197 10.1371/journal.pone.0058197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riès SK, Dhillon RK, Clarke A, King-Stephens D, Laxer KD, Weber PB, … Knight RT. (2017). Spatiotemporal dynamics of word retrieval in speech production revealed by cortical high-frequency band activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(23), E4530–E4538. 10.1073/pnas.1620669114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlösser R, Hutchinson M, Josever S, Rusinek H, Saarimaki A, Stevenson J, … Brodie JD (1998). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity in a verbal fluency task. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 64, 492–498. 10.1136/jnnp.64.4.492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sederberg PB, Kahana MJ, Howard MW, Donner EJ, & Madsen JR (2003). Brief Communication Theta and Gamma Oscillations during Encoding Predict Subsequent Recall. Retrieved from http://fechner.ccs.brandeis.edu/wordpools.php [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sederberg PB, Schulze-Bonhage A, Madsen JR, Bromfield EB, Litt B, Brandt A, & Kahana MJ (2007). Gamma Oscillations Distinguish True From False Memories. Psychological Science, 15(11), 927–932. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02003.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z, Janse E, Visser K, & Meyer AS (2014). What do verbal fluency tasks measure? Predictors of verbal fluency performance in older adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 772 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon S, & Moscovitch M (2012). The nature and time-course of medial temporal lobe contributions to semantic retrieval: An fMRI study on verbal fluency. Hippocampus, 22(6), 1451–1466. 10.1002/hipo.20985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson DJ (1982). Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proceedings of the IEEE, 70(9), 1055–1096. 10.1109/PROC.1982.12433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]