The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant challenges to clinics specializing in the care of patients with serious mental illness (SMI). Our ambulatory clinic, Comprehensive Recovery Services of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Western Psychiatric Hospital serves around 1500 patients, most with psychotic disorders. A COVID-19 State of Emergency was declared on March 13, 2020, in the United States, and by March 16, social distancing began in earnest to mitigate contagion risks associated with the virus. While most of our face to face clinic visits were quickly shifted to phone and video appointments, it was clear that certain in person encounters with patients were needed to ensure patient stability during this stressful period. One such visit type was for the administration of long acting antipsychotic injections (LAIs).

LAIs are considered a mainstay treatment in persons with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (Kishimoto et al., 2013). In the United States, LAIs on the market include different formulations of aripiprazole, risperidone, paliperidone, fluphenazine, and haloperidol and are administered at regularly prescribed intervals ranging from 2 weeks to 3 months. LAIs are considered the ideal treatment for patients who have cognitive impairment and/or variable insight affecting oral medication adherence, and evidence suggests that they reduce hospitalizations (Marcus et al., 2015; Greene et al., 2018). While our clinic does offer in home nursing services that can administer LAIs, it is only for a select few. As such, and given the delivery systems, refrigeration requirements, and intramuscular injection techniques associated with various LAIs that would make them potentially unsafe for patient self or caregiver administration, continuing to provide in person LAI injection services was of paramount importance.

While many patients recognize the importance of obtaining their LAIs as scheduled, we became concerned that patients would refuse to come into our clinic to obtain them. We anticipated that some patients would cite concerns around adequate social distancing or be fearful of information or misinformation they encountered about the virus. As illustrated in a recent report (Ifteni et al., 2020), we thus prepared to transition many LAI patients to oral medications, despite concerns about adherence and a lack of clear guidance on how best to return patients to oral medications. Given these concerns, and to reduce risk of transmission to patients and staff, we implemented clinical workflows to screen patients for COVID-19 symptoms and exposure (performed via phone pre-arrival and at registration upon patient arrival). We staggered patient appointment times, amply supplied hand sanitizer, removed chairs in the waiting area to ensure maintenance of over 6 ft of space between patients, and expanded our waiting room capacity to currently unused conference rooms to further minimize contact between patients. Nurses administering the injections were masked and gloved, and when community masking was indicated, we instructed patients to mask and provided masks when they presented without. These measures were carefully described to patients or caregivers who expressed concerns. Despite our workflow changes, we remained concerned that, as reductions were made in our public transportation systems, lower socioeconomic status patients would face issues with clinic access that were beyond their or our control. Finally, we also worried that some patients would become more symptomatic and/or less insightful into the need for treatment, influencing their decision to discontinue the LAI.

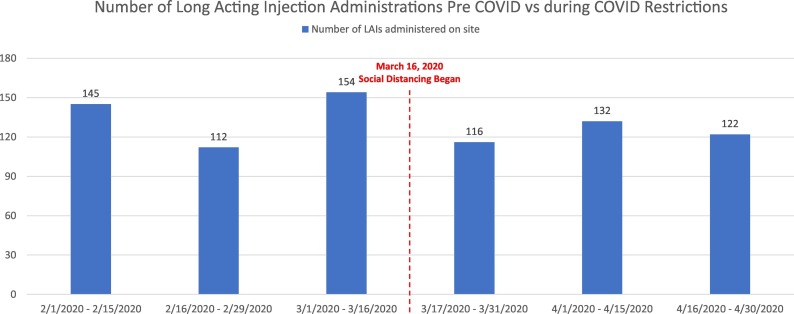

When we tallied the data for a 6-week mirror-image time period encompassing the Pre-COVID and COVID restrictions (see Fig. 1 ), the numbers of LAIs administered by our injection nurses were essentially unchanged, a reduction of only 10%. Only 4 LAI patients were switched over to oral antipsychotic medication at their request.

Fig. 1.

Number of long acting injection administrations pre-COVID vs during COVID restrictions.

Why do our numbers diverge from the published Romanian dataset (Ifteni et al., 2020) and perhaps others that may emerge? First, thus far, Pittsburgh and the surrounding region has not been a hot spot for COVID-19 transmission. Second, workflows to serve SMI patients in person (especially the LAI and clozapine clinics) were reviewed thoughtfully and implemented rapidly. Personal protective equipment was obtained and used immediately. Third, talking points around the need for continued in person visits for LAIs and the importance of ongoing adherence to medications was underscored and reviewed with all involved staff to share with our patients, their caregivers and families. Moreover, the LAI clinic has been serving SMI patients for over 25 years with a low staff turnover, and a collocated pharmacy adjacent to our LAI administration room is heavily used by our patients. The rapport that nursing and pharmacy staff have with our patients likely bolstered trust.

A delayed injection schedule has been suggested if the pandemic is prolonged (Ifteni et al., 2020). However, unless LAIs are formulated to be delivered in flexible dosing intervals outside the approved schedules (e.g. every 6 weeks instead of every 4 weeks, etc.), data to guide such off-label practice will be anecdotal at best.

Sponsorship and sources of funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest with reference to this article.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Joan Spinogatti for facilitating author collaboration and contributions, and Forbes pharmacy staff for their compassionate care and counseling to the patients.

References

- Greene M., Yan T., Chang E. Medication adherence and discontinuation of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J. Med. Econ. 2018;21(2):127–134. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1379412. Feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifteni P., Dima L., Teodorescu A. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics treatment during COVID-19 pandemic – a new challenge. Schizophr. Res. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.030. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T., Nitta M., Borenstein M. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S.C., Zummo J., Pettit A.R. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754–768. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.9.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]