Abstract

Background and aim

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare chronic form of hepatitis, the prognosis for which has not been definitively established. The current study aimed to define the prognostic factors for remission and compare the median time to remission, complications, and relapse rate between type 1 AIH patients treated with prednisolone monotherapy and those treated using prednisolone in combination with azathioprine.

Materials and methods

The data of 86 patients diagnosed with type 1 AIH between January 1998 and January 2018 were retrospectively reviewed. Clinical, serological, and histological parameters were obtained. Cox-proportional hazard and logistic regression analyses were applied to the data.

Results

The prognostic factors related to complete remission were absence of liver cirrhosis, hypertension, and azathioprine exposure. The median time to complete remission of the prednisolone group (92 days; 95%CI; 65–264 days) was significantly shorter (P = 0.01) than that of the combination group (336 days; 95%CI; 161–562 days); however, the prednisolone group had higher rates of treatment complications—including skin and soft tissue infections (P = 0.010) and cushingoid appearance (P = 0.011)—than the combination group. The prednisolone group also had a higher relapse rate (odds ratio 6.13, 95% CI 1.72–21.80, P = 0.005).

Conclusions

The absence of liver cirrhosis and hypertension at the time of diagnosis and no azathioprine exposure during the treatment period were favorable prognostic factors for complete remission. The prednisolone group had a significantly shorter median time to complete remission but higher rates of treatment complications and a higher relapse rate than the combination group.

Keywords: Hepatology, Health sciences, Evidence-based medicine, Internal medicine, Clinical research, Autoimmune hepatitis, Azathioprine, Prednisolone, Prognostic factor, Remission

Hepatology; Health Sciences; Evidence-Based Medicine; Internal Medicine; Clinical Research; Autoimmune hepatitis, azathioprine, prednisolone, prognostic factor, remission

1. Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare chronic form of hepatitis characterized by specific liver histopathology, blood biochemistry, and serology with a prevalence of 11–25 per 100,000 population [1]. Autoimmune hepatitis is more common among females and often appears at between 40 and 50 years of age [2, 3]. AIH has two types: type 1 AIH which is defined by the presence of circulating antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA); and type 2 which is characterized by the presence of antibodies to liver/kidney microsomes (ALKM-1) and/or to a liver cytosol antigen (ALC-1) [2, 4]. Liver cirrhosis and liver failure usually occur in patients with untreated or unresponsive to treatment, and such patients are at risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma [5].

Standard first-line immunosuppressive treatment of autoimmune hepatitis comprises one of two regimens, which are equally effective against severe AIH: (a) high-dose prednisolone monotherapy or half-dose prednisolone therapy in conjunction with azathioprine [6, 7]. Prednisolone monotherapy is appropriate for patients with cytopenia, thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency, pregnancy, or malignancy [8]. The combination therapy results in fewer corticosteroid side-effects and is preferred for patients with brittle diabetes, osteoporosis, obesity, or hypertension, or who are post-menopausal or emotionally unstable. Untreated AIH has a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 50% and 10-year survival rate of 10% [9]. Immunosuppressive therapy significantly improves survival, with 90% of treated AIH patients achieving complete remission [7, 10, 11, 12]. Some small studies have shown that cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis—with a high MELD score, high AST/ALT, high serum IgG, or overlapping syndromes—is associated with poor treatment outcomes [11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Notwithstanding, the median time to remission, prognostic factors of remission, relapse rate, and complication rate of the two treatment regimens in AIH patients have not been compared.

The current study thus aimed to define the prognostic factors for remission and compared the median time to remission, complications, and relapse rate between type 1 AIH patients treated with prednisolone monotherapy and those given a combination regimen.

2. Materials and methods

This was a retrospective study conducted at Srinagarind Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University. Our protocol was approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research (Reference No.HE601224). We reviewed the records of patients with AIH registered in the hospital's electronic medical records between January 1998 and January 2018. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis with AIH based on the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group's simplified diagnostic criteria [18], any the Child Pugh score including overlapping diseases [19, 20, 21] from the in- or out-patient department, and being at least 18 years of age. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had a history of liver transplantation, and diagnosed with other conditions such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, lupus hepatitis, and herb-induced hepatitis.

Patient clinical data and laboratory results were collected from both electronic and paper medical records. At their initial visit, all eligible patients were assessed based on serum biochemistry, serum immunoglobulins, serum autoantibodies, viral markers, and liver histology. According to the simplified diagnostic criteria [18], patients with greater than 6 points, 6 points, and less than 6 points, were classified as having definite, probable, and possible AIH, respectively. At subsequent follow-up visits, each patient treatment regimen, additional medications, follow-up laboratory results, and treatment complications were recorded until the treatment endpoint had been reached. The treatment endpoint was classified as a) complete remission – defined as the disappearance of symptoms and normal serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels; b) incomplete remission – defined as some or no improvement in clinical and laboratory results despite compliance with therapy after 2–3 years; and, c) treatment failure – defined as worsening of clinical and laboratory results despite compliance with therapy [2].

The primary outcome was prognostic factors for remission of AIH. The secondary outcomes were differences in median time to AIH remission, complication rates, and relapse rates between patients given prednisolone monotherapy and those treated with prednisolone in combination with azathioprine. The baseline characteristics of each treatment endpoint were compared using descriptive statistics. Differences in median time to remission between the two groups were analyzed and summarized using Kaplan-Meier curves. The Cox-proportional hazard model was applied to calculate the crude hazard ratios of variables associated with complete remission. Multivariable analysis was performed to calculate the adjusted hazard ratios. Pearson's chi-squared test was applied to compare the treatment complications between the two regimens. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio of the relapse rates of the two regimens. All analyses were performed using STATA and RStudio software.

3. Results

During the 20-year study period, a total of 239 patients were registered as having autoimmune hepatitis at Srinagarind Hospital, 86 of whom were diagnosed with type 1 AIH and enrolled in the current study (Figure 1). The others were diagnosed with other conditions such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, lupus hepatitis, and herb-induced hepatitis. Initial treatment included prednisolone monotherapy (n = 42) and prednisolone in combination with azathioprine (n = 44). Sixty-two of the 86 enrolled patients (72.1%) experienced complete remission, while 13 (15.1%) and 11 (12.8%) had incomplete remission and were lost to follow-up, respectively. No patients experienced treatment failure. The average duration of follow-up was 2 years (SD 3 years). Baseline characteristics and laboratory results by treatment endpoint are shown in Table 1. Eighty percent of patients were female. There were no significant differences in age, BMI, or azathioprine exposure among the three groups. The majority (67.4%) of patients was considered to have possible autoimmune hepatitis based on the autoimmune hepatitis diagnostic criteria. The number of patients with no underlying diseases was significantly lower in the incomplete remission group than in the other two groups, while the number of patients with hypertension was significantly greater. Serum albumin was significantly lower and serum total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were significantly higher in the lost to follow-up group than the other groups. Diagnostic classifications, ultra-sonographic findings, liver histopathology, and the Child-Pugh scores differed significantly among the three groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient enrollment, endpoints, treatments, and relapse. Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; EMR, electronic medical record.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical data and demographic characteristics categorized by treatment endpoint.

| Complete remission (n = 62) | Incomplete remission (n = 13) | Lost to follow-up (n = 11) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years§ | 52 (45–60) | 48 (41–59) | 54 (48–65) | 0.550 |

| Sex, female¶ | 49 (79.0) | 13 (100) | 7 (63.6) | 0.075 |

| BMI, kg/m2§ |

23.5 (21.1–25.8) |

23.1 (21.9–24.0) |

22.3 (19.7–31.4) |

0.723 |

| Underlying disease¶ | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (9.7) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0.261 |

| Hypertension | 4 (6.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | 0.012∗ |

| Dyslipidemia | 15 (24.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 0.188 |

| Thyroid disease | 3 (4.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0.816 |

| PBC (overlap syndromes) | 4 (6.5) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (18.2) | 0.137 |

| SLE | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.548 |

| No underlying disease |

28 (45.2) |

1 (7.7) |

7 (63.6) |

0.013∗ |

| Criteria diagnosis¶ |

0.002∗ |

|||

| Definite | 9 (14.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Probable | 8 (12.9) | 4 (30.8) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Possible |

45 (72.6) |

9 (69.2) |

4 (36.4) |

|

| Ultrasonography¶ |

0.001∗ |

|||

| Normal | 26 (41.6) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Parenchymatous change | 26 (41.6) | 7 (53.8) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Cirrhosis |

9 (14.8) |

3 (23.1) |

8 (72.7) |

|

| Liver histopathology¶ |

0.035∗ |

|||

| Typical/compatible | 29 (46.7) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Negative | 13 (21.0) | 5 (38.4) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Not done |

20 (32.3) |

2 (15.4) |

8 (72.7) |

|

| Lab§ |

||||

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.0 (31.3–38.2) | 33.6 (31.0–34.0) | 33.0 (30.0–38.0) | 0.222 |

| White blood cells (cell/mm3) | 7,000 (5,800–8,700) | 6,300 (4,800–8,900) | 9,100 (6,400–12,800) | 0.293 |

| Platelets (/mm3) | 241,500 (166,500–294,000) | 118,000 (104,500–296,000) | 175,000 (75,000–219,000) | 0.021∗ |

| INR | 1.29 (1.09–1.47) | 1.07 (0.96–1.08) | 1.49 (1.37–2.08) | 0.008∗ |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 (3.2–4.3) | 3.5 (3.3–4.0) | 2.8 (2.6–2.9) | <0.001∗ |

| TB (mg/dL) | 3.3 (0.9–16.6) | 3.6 (1.2–7.6) | 12.8 (3.9–16.6) | 0.195 |

| ALT (U/L) | 162 (84–482) | 105 (78–158) | 90 (71–197) | 0.049∗ |

| AST (U/L) | 230 (96–585) | 120 (71–257) | 155 (105–225) | 0.246 |

| ALP (U/L) | 127 (99–193) | 183 (104–374) | 235 (144–316) | 0.023∗ |

| AST/ALT ratio |

1.4 (0.7–1.8) |

1.1 (1.0–1.8) |

1.8 (1.1–2.1) |

0.310 |

| Child-Pugh score¶ |

0.004∗ |

|||

| A | 29 (50.9) | 6 (50.0) | 0 (0) | |

| B | 25 (43.9) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (63.6) | |

| C | 3 (5.3) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Combination treatment¶ | 32 (51.6) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (36.4) | 0.465 |

P values calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test or Pearson's chi-squared test.

Abbreviations: PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; INR, international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Data presented as median (1st – 3rd quartile range).

Data presented as number (percentage).

The baseline characteristics and laboratory results according to the autoimmune hepatitis treatment regimens are presented in Table 2. The mean initial dose of prednisolone in the prednisolone monotherapy group was 45 ± 15 (range, 20–60 mg), while the mean initial dose of prednisolone and azathioprine in the combination group was 20 ± 13 (range, 10–60 mg) and 91 ± 29 (range, 50–150 mg), respectively. There were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, diagnostic criteria, ultra-sonographic findings, liver histopathology, the Child-Pugh scores, and the treatment endpoint between the two groups. The number of patients with primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndromes was significantly higher in the combination group, while patients with no underlying disease(s) was significantly lower. Serum aspartate aminotransferase was significantly higher in the prednisolone monotherapy group.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical data and demographic characteristics categorized by autoimmune hepatitis treatment regimens.

| Prednisolone (n = 42) | Combination (n = 44) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years§ | 50 (43–60) | 54 (46–60) | 0.409 |

| Sex, female¶ | 35 (83.3) | 34 (77.3) | 0.481 |

| BMI, kg/m2§ |

23.3 (21.5–25.6) |

23.6 (20.6–26.0) |

0.983 |

| Underlying disease¶ | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (7.1) | 8 (18.2) | 0.125 |

| Hypertension | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.1) | 0.945 |

| Dyslipidemia | 8 (19.0) | 10 (22.7) | 0.675 |

| Thyroid disease | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.1) | 0.184 |

| PBC (overlap syndromes) | 1 (2.4) | 8 (18.2) | 0.017∗ |

| SLE | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.3) | 0.529 |

| No underlying disease |

23 (54.8) |

13 (29.5) |

0.018∗ |

| Criteria diagnosis¶ |

0.136 |

||

| Definite | 6 (14.3) | 3 (6.8) | |

| Probable | 12 (28.6) | 7 (15.9) | |

| Possible |

24 (57.1) |

34 (77.3) |

|

| Ultrasonography¶ |

0.703 |

||

| Normal | 15 (35.7) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Parenchymatous change | 16 (38.1) | 19 (43.2) | |

| Cirrhosis |

11 (26.2) |

9 (20.5) |

|

| Liver histopathology¶ |

0.797 |

||

| Typical/compatible | 19 (45.2) | 18 (40.9) | |

| Negative | 8 (19.0) | 11 (25.0) | |

| Not done |

15 (35.7) |

15 (34.1) |

|

| Lab§ |

|||

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.0 (30.5–37.1) | 34.3 (31.9–38.0) | 0.791 |

| White blood cells (cell/mm3) | 7,910 (5,900–10,200) | 6,800 (5,400–8,750) | 0.239 |

| Platelets (/mm3) | 216,000 (161,000–279,500) | 217,000 (127,000–281,000) | 0.824 |

| INR | 1.36 (1.07–1.49) | 1.24 (1.03–1.48) | 0.319 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 (2.9–3.9) | 3.6 (3.0–4.3) | 0.365 |

| TB (mg/dL) | 6.2 (1.1–16.0) | 2.9 (1.0–9.9) | 0.386 |

| ALT (U/L) | 188 (82–518) | 138 (79–269) | 0.261 |

| AST (U/L) | 248 (120–705) | 157 (69–256) | 0.023∗ |

| ALP (U/L) | 142 (97–237) | 130 (106–225) | 0.832 |

| AST/ALT ratio |

1.5 (1.0–1.9) |

1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

0.060 |

| Child-Pugh score¶ |

0.485 |

||

| A | 14 (36.8) | 21 (50.0) | |

| B | 20 (52.6) | 17 (40.5) | |

| C |

4 (10.5) |

4 (9.5) |

|

| Treatment endpoint¶ |

0.465 |

||

| Complete remission | 30 (71.4) | 32 (72.7) | |

| Incomplete remission | 5 (11.9) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 (16.7) | 4 (9.1) | |

P values calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Pearson's chi-squared test.

Abbreviations: PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; INR, international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Data presented as median (1st – 3rd quartile range).

Data presented as number (percentage).

The Cox-proportional hazard model revealed that the prognostic factors related to complete remission included absence of liver cirrhosis, hypertension, and azathioprine exposure, whereas age, sex, BMI, and the initial liver function test were not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prognostic factors for complete remission in autoimmune hepatitis.

| Univariate Cox hazard analysis |

Multivariate Cox hazard analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.052 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.206 |

| Azathioprine exposure | 0.67 (0.41–1.12) | 0.128 | 0.49 (0.28–0.84) | 0.009∗ |

| Female | 0.72 (0.39–1.33) | 0.294 | - | - |

| BMI | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 0.582 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 0.35 (0.12–0.97) | 0.043∗ | 0.16 (0.05–0.54) | 0.003∗ |

| Cirrhosis§ | 0.48 (0.24–0.98) | 0.045∗ | 0.37 (0.18–0.76) | 0.007∗ |

| Child Pugh score | 0.76 (0.50–1.14) | 0.185 | - | - |

| Platelets | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.076 | - | - |

| Albumin | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.065 | - | - |

| TB | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.755 | - | - |

| ALT | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.072 | - | - |

| AST | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.078 | - | - |

| ALP | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.033∗ | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.050 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 0.953 | ||

| PBC overlap | 0.39 (0.14–1.07) | 0.068 | - | - |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; TB, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis.

Cirrhosis was diagnosed by ultrasonography.

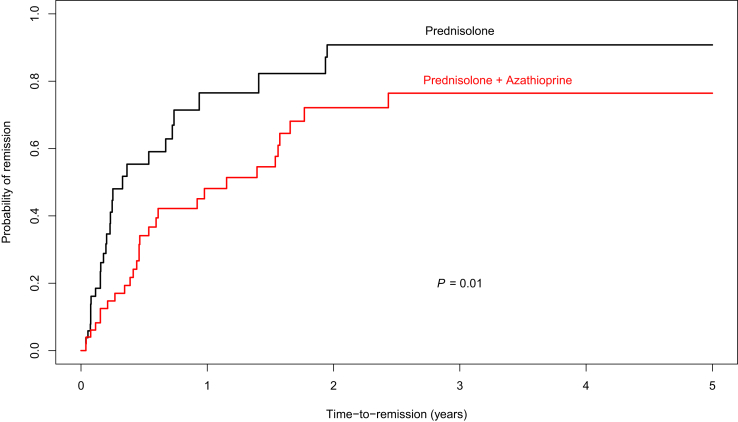

Median time to complete remission in the prednisolone monotherapy group was 92 days (95%CI 65–264 days) and 336 days (95%CI 161–562 days) in the combination group (Figure 2). After adjusting for covariates (age, hypertension, cirrhosis, and alkaline phosphatase), the prednisolone monotherapy group had a significantly shorter median time to complete remission than the combination group (P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Median time to complete remission in patients given the prednisolone monotherapy regimen and those who underwent combination regimen was 92 days (95%CI 65–264) and 336 days (95%CI 161–562), respectively, with a P of 0.01. Total median time to remission was 170 days (95%CI 126–336).

The prednisolone monotherapy group had higher rates of skin and soft tissue infections (P = 0.01) and Cushingoid appearance (P = 0.01), but there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of other side effects (cytopenia, myopathy, hyperglycemia, pneumonia, bacteremia, and urinary tract infection; Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of complication rates between two autoimmune hepatitis treatment regimens.

| Prednisolone n = 42 (%) | Combination n = 44 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | |||

|

3 (7.1) | 2 (4.5) | 0.607 |

|

10 (23.8) | 2 (4.5) | 0.010∗ |

|

1 (2.4) | 2 (4.5) | 0.584 |

|

1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0.303 |

| Cytopenia | 3 (7.1) | 8 (18.2) | 0.125 |

| Muscle weakness | 3 (7.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0.284 |

| Cushing appearance | 8 (19.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.011∗ |

| Hyperglycemia§ | 5 (11.9) | 4 (9.1) | 0.670 |

Hyperglycemia that leads patients to be admitted or treated with antihyperglycemic drugs.

In addition, the prednisolone monotherapy group had a higher relapse rate than the combination group (odds ratio 6.13, 95% CI 1.72–21.80, P = 0.005).

4. Discussion

About 80% of the AIH patients in Srinagarind Hospital were middle-aged woman, as were patients in previous studies [2, 3]. The complete remission rate in the current study was 72.1%, which is slightly higher than that reported by Czaj et al. [22]. The group with an incomplete response had nearly double the negative histology for AIH as the responsive group, which may be the reason that treatment was not effective. There have not been any previous studies that have compared median time to remission between these two treatment regimens. Our study found that patients getting the prednisolone monotherapy had a significantly shorter median time to complete remission than patients getting the combination therapy. The total median time to complete remission was 170 days, which was longer than that found in a previous study [10]; this may be explained a higher initial dose of prednisolone leading to a shorter time to remission. A previous real-world study suggested that an initial prednisolone dose of 40 mg/day with a slower tapering protocol induced an earlier biochemical response than an initial prednisolone dose of 30 mg/day [23].

As with previous reports, the current study confirmed that liver cirrhosis at the time of AIH diagnosis was a significant poor prognostic factor for treatment outcome [11, 13, 14, 15, 16]. We also found that absence of hypertension at the time of AIH diagnosis and absence of azathioprine exposure during the treatment period were good prognostic factors for complete remission. Although previous studies reported that younger age, low serum albumin, and high total bilirubin at the time of diagnosis were poor prognostic factors, the current study did not confirm this [13, 14, 15].

There have not yet been any reports comparing treatment complications between these two treatment regimens. The current study was thus the first to report that the rates of skin and soft tissue infection and Cushingoid appearance in patients treated using the single prednisolone regimen were significantly higher than in those receiving azathioprine with a reduced dosage of prednisolone.

Autoimmune hepatitis has a high relapse rate [24], and relapse usually occurs within 12 months after remission [25, 26]. There have, however, been no studies comparing the relapse rates of autoimmune hepatitis treatment regimens. Our study was thus the first to find that the single prednisolone regimen had about a six-times higher relapse rate than azathioprine with a reduced dosage of prednisolone.

The strengths of the current study are that (a) it was larger than previous retrospective studies [15, 27] and (b) had an average duration of follow-up of 2 years with only a 12% dropout rate. There were, however, some limitations. First, diagnostic liver biopsy could not be performed in some patients (35%) due to their inability to afford the cost of the procedure and unwillingness to accept risk of procedural complications. Second, serum IgG and serum antinuclear antibody titer measurements have only been available in our laboratory for the past few years. Third, our center did not perform liver biopsy to confirm the remission stage due to financial constraints and patient refusal, so we based our remission assessments on symptoms and the normalization of liver function test results. Fourth, data were collected retrospectively and some information was unavailable (i.e., the maintenance dose of prednisolone and long-term complications of prolonged steroid treatment).

In conclusion, the absence of liver cirrhosis and hypertension at the time of diagnosis and no azathioprine exposure during the treatment period were good prognostic factors for complete remission. Patients receiving prednisolone monotherapy had a significantly shorter median time to complete remission than patients receiving a combination therapy. Notwithstanding, patients receiving the combination therapy had lower rates of treatment complications and relapse than those receiving the prednisolone monotherapy.

Key points.

-

-

Absence of liver cirrhosis and hypertension at diagnosis and no azathioprine exposure during treatment were favorable prognostic factors for complete remission of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis.

-

-

The prednisolone monotherapy group had a significantly shorter median time to complete remission, but higher rates of treatment complications and a higher relapse rate than the combination group.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

N. Sandusadee and T. Suttichaimongkol: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

W. Sukeepaisarnjaroen: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank (a) Associate Professor Sirirat Anutrakulchai and Assistant Professor Anupol Panitchote for their valuable comments on the statistical analysis, (b) Professor Sombat Treeprasertsuk for assistance in improving the manuscript, and Mr. Bryan Roderick Hamman for assistance with the English-language presentation of the manuscript under the aegis of the Publication Clinic KKU, Thailand.

References

- 1.Krawitt E.L. Autoimmune hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:54–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manns M.P., Czaja A.J., Gorham J.D., Krawitt E.L., Mieli-Vergani G., Vergani D. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boberg K.M., Aadland E., Jahnsen J., Raknerud N., Stiris M., Bell H. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;33:99–103. doi: 10.1080/00365529850166284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manns M., Gerken G., Kyriatsoulis A., Staritz M., Meyer zum Büschenfelde K.H. Characterisation of a new subgroup of autoimmune chronic active hepatitis by autoantibodies against a soluble liver antigen. Lancet. 1987;1:292–294. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeoman A.D., Al-Chalabi T., Karani J.B., Quaglia A., Devlin J., Mieli-Vergani G. Evaluation of risk factors in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for follow-up and screening. Hepatology. 2008;48:863–870. doi: 10.1002/hep.22432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montano Loza A.J., Czaja A.J. Current therapy for autoimmune hepatitis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;4:202–214. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B., Mieli-Vergani G., Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis: standard treatment and systematic review of alternative treatments. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6030–6048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Summerskill W.H., Korman M.G., Ammon H.V., Baggenstoss A.H. Prednisone for chronic active liver disease: dose titration, standard dose, and combination with azathioprine compared. Gut. 1975;16:876–883. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.11.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi P.J., Hirschfield G.M. Treatment of autoimmune liver disease: current and future therapeutic options. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2013;4:119–141. doi: 10.1177/2040622313478646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czaja A.J., Rakela J., Ludwig J. Features reflective of early prognosis in corticosteroid-treated severe autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:448–453. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montano-Loza A.J., Carpenter H.A., Czaja A.J. Features associated with treatment failure in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis and predictive value of the model of end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1138–1145. doi: 10.1002/hep.21787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jothimani D., Cramp M.E., Mitchell J.D., Cross T.J.S. Treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: a review of current and evolving therapies. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;26:619–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muratori P., Lalanne C., Bianchi G., Lenzi M., Muratori L. Predictive factors of poor response to therapy in Autoimmune Hepatitis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016;48:1078–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngu J.H., Gearry R.B., Frampton C.M., Stedman C.A.M. Predictors of poor outcome in patients w ith autoimmune hepatitis: a population-based study. Hepatology. 2013;57:2399–2406. doi: 10.1002/hep.26290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hino T., Kumashiro R., Ide T., Koga Y., Ishii K., Tanaka E. Predictive factors for remission and death in 73 patients with autoimmune hepatitis in Japan. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003;11:749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang F., Wang Q., Bian Z., Ren L.-L., Jia J., Ma X. Autoimmune hepatitis: east meets west. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;30:1230–1236. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Chalabi T., Portmann B.C., Bernal W., McFarlane I.G., Heneghan M.A. Autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromes: an evaluation of treatment response, long-term outcome and survival. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;28:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennes E.M., Zeniya M., Czaja A.J., Parés A., Dalekos G.N., Krawitt E.L. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–176. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czaja A.J. The overlap syndromes of autoimmune hepatitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013;58:326–343. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boberg K.M., Chapman R.W., Hirschfield G.M., Lohse A.W., Manns M.P., Schrumpf E. Overlap syndromes: the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) position statement on a controversial issue. J. Hepatol. 2011;54:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anić F., Zuvić-Butorac M., Stimac D., Novak S. New classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus correlate with disease activity. Croat. Med. J. 2014;55:514–519. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2014.55.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czaja A.J., Menon K.V.N., Carpenter H.A. Sustained remission after corticosteroid therapy for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:890–897. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purnak T., Efe C., Kav T., Wahlin S., Ozaslan E. Treatment response and outcome with two different prednisolone regimens in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017;62:2900–2907. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czaja A.J., Ammon H.V., Summerskill W.H. Clinical features and prognosis of severe chronic active liver disease (CALD) after corticosteroid-induced remission. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleeson D., Heneghan M.A., British Society of Gastroenterology British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611–1629. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.235259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gerven N.M.F., Verwer B.J., Witte B.I., van Hoek B., Coenraad M.J., van Erpecum K.J. Relapse is almost universal after withdrawal of immunosuppressive medication in patients with autoimmune hepatitis in remission. J. Hepatol. 2013;58:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeoman A.D., Westbrook R.H., Zen Y., Bernal W., Al-Chalabi T., Wendon J.A. Prognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): the role of corticosteroids in modifying outcome. J. Hepatol. 2014;61:876–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]