Abstract

Novel processing technologies can be used to improve both the microbiological safety and quality of food products. The application of high pressure processing (HPP) in combination with dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) represents a promising alternative to classical thermal technologies. This research work was undertaken to investigate the combined effect of HPP and DMDC, which was aimed at reaching over 5-log reduction in the reference pathogens Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in apple juice. Different strains of each species were tested. The pressure (ranging from 100 to 600 MPa), dwell time (from 26 to 194 s), and DMDC (from 116 to 250 mg/L) were tested based on a central composite rotatable design. The dwell time, in the studied range, did not have a significant effect (p > 0.1) on the pathogens´ reduction. All treatments achieved a greater than 5-log reduction for E. coli O157:H7 and L. monocytogenes. The reductions for S. enterica were also greater than 5-log for almost all tested combinations. The results for S. enterica suggested that it is more resistant to HPP and DMDC compared with E. coli O157:H7 and L. monocytogenes. The findings of this study showed that DMDC at low concentrations can be added to apple juice to reduce the parameters conventionally applied in HPP. The combined use of HPP and DMDC was highly effective under the conditions of this study.

Keywords: Hurdle technology, Nonthermal processing, Microbial inhibitor, Factorial design

Introduction

Hurdle technology, known as combined methods or barrier technology, shows interaction effects while using various mechanisms for the inhibition or inactivation of targeted microorganisms [1]. Food preservation frequently relies on the combined application of several preservation methods [2]. Because consumers are more demanding for products which have natural flavor and higher nutritive value, high pressure processing (HPP) has been considered one of the preferred technologies to meet these consumer preferences.

Balasubramaniam and Farkas [3] state that HPP offers a commercially viable and practical alternative to thermal processing by allowing food processors to process foods at or near ambient temperature. HPP can effectively inactivate pathogenic and spoilage bacteria, yeasts, and molds, but have limited effectiveness against spores and enzymes. According to Kan et al. [1], food products with a high acid content are particularly favorable candidates for HPP technology. The pressure resistance of Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes exhibits significant variability, which is biotype/strain specific. For food applications, the minimum and maximum limits of HPP are 200 MPa and 600 MPa, respectively [1]. Notwithstanding, effective preservation using HPP may be achieved at moderate pressures in combination with other hurdles, which result in synergistic effects of two or more suitable antimicrobial factors at moderate doses.

Huang et al. [4] reported that HPP eliminates food pathogens at ambient temperature and extends the shelf life of foods circulated through the cold chain. HPP maintains the sensory properties and nutritional value of the foods, which is not possible using traditional thermal pasteurization. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has officially recognized HPP as a nonthermal pasteurization technology that can replace traditional thermal processing in the food industry, primarily for acid foods.

Combining HPP with additional hurdles and milder processing treatments may help reduce processing costs and allow wider industrial adaptation of HPP. Because the maintenance costs of the HPP equipment exponentially increase with pressures beyond 600 MPa, significant reductions in processing pressure requirements are highly desirable [3].

As far as microbial inhibitors are concerned, dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) is primarily used as a yeast inhibitor, but also shows inhibitory activity against molds and bacteria [5]. DMDC, a dicarbonic acid ester, is a colorless, transparent liquid with a fruity aroma. It is a powerful antimicrobial agent due to its potentially high reaction capacity with nucleophilic groups of enzymes from microorganisms, such as imidazoles, amines, or thiols, which results in the rapid inactivation of microorganisms [6]. DMDC in water solutions can be rapidly and completely hydrolyzed into low levels of methanol and carbon dioxide, which are both natural constituents of fruits and vegetables, proven to be harmless [7]. Because the hydrolysis products are nontoxic to consumers, DMDC is not required to be declared in the product label by the FDA [8]. DMDC is FDA approved for use as a microbial inhibitor with the maximum limit of 250 mg/L. In this context, the combined use of HPP and DMDC may represent a promising hurdle approach to reduce the high pressure processing conditions. Lindner et al. [9] added DMDC as preservation method to a functional fruit/vegetable beverage (pH 3.5). Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris and E. coli were inoculated in the beverage to induce spoilage. The DMDC reduced E. coli to undetectable levels and exhibited a greater reduction of A. acidoterrestris vegetative cells, molds and yeasts.

This research work was conducted to evaluate the combined effect of HPP and DMDC, which was aimed at reaching over 5-log reduction in the reference pathogens Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in shelf stable apple juice.

Material and methods

The experiments were conducted at the Cornell High Pressure Processing Validation Center. The facility includes the high pressure processing area and the biohazard level 2 laboratory in the Food Science Building at the Cornell AgriTech Campus, in Geneva, NY, USA. The strains selected for this study are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Serotypes/strains and origin of the pathogens used in the study

| Pathogen | Strain or serotype | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli O157:H7 | C7927 | Human isolate, apple cider linked to an outbreak (date of outbreak unavailable) |

| ATCC 43890 | Human isolate, date of outbreak unavailable | |

| ATCC 43894 | Human isolate, date of outbreak unavailable | |

| ATCC 43889 | Human isolate, date of outbreak unavailable | |

| ATCC 35150 | Human isolate, date of outbreak unavailable | |

| S. enterica | Hartford H0778 | Orange juice, US outbreak in 1995 |

| Typhimurium FSL R9-5494 | Orange juice, multistate US outbreak in 2005 | |

| Muenchen FSL R9-5498 | Alfalfa sprouts, multistate US outbreak in 2016 | |

| Javiana FSL R9-5273 | Tomatoes, multistate US outbreak in 2002 | |

| Enteriditis FSL-R9-5505 | Beans sprouts, multistate US outbreak in 2014 | |

| L. monocytogenes | Lineage I, serotype 4b FSL J1-108 | Coleslaw, US outbreak in 1981 |

| Lineage I, serotype 4d FSL J1-107 | Coleslaw, US outbreak in 1981 | |

| Lineage II, serotype 1/2a FSL R9-0506 | Cantaloupe, US outbreak in 2011 | |

| FSL R9-5411 | Caramel Apple, multistate US outbreak 2014–2015 | |

| FSL R9-5506 | Packaged Salad, multistate US outbreak in 2016 |

The pathogen pools were selected based on their produce-related outbreaks, which matches the apple juice

Inoculum preparation

Frozen stocks of pathogenic E. coli O157:H7, S. enterica, and L. monocytogenes were kept at − 80 °C until used. Thawed stocks were reactivated by streaking onto trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates and incubated overnight at 36 ± 1 °C. After the streaked culture was grown, the plate was placed at 4 °C. A single isolated colony of each pathogen strain was separately transferred into 10 mL of trypticase soy broth (TSB) and incubated for 24 h at 36 ± 1 °C under shaking (175 rpm). This procedure was carried out for all pathogens used in the study. A loop of the inoculated TSB was then transferred into a volume of 10 mL TSB (pH 5.0) and incubated for 24 h at 35 ± 1 °C under shaking (175 rpm). Acid adaptation of the cells with citric acid was performed based on the protocol carried out by Usaga et al. [10]. After incubation, cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 2 min using an Eppendorf 5415 C microcentrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and resuspended in 1 mL of citrate buffer (pH 4.0) diluent. A pool of five strains/serotypes of each pathogen was prepared by equivalent volumes of cells being combined and serving as the pool inoculum for the apple juice.

Food matrix

As food matrix, 1.9-L PET bottles of shelf stable preservatives free, 100% apple juice (Wegmans Food Markets, Inc. Rochester, NY, USA), were procured from local supermarket in Geneva, NY. The apple juice was separately inoculated with five-strain pools of each of the three pathogens (Table 1).

Physicochemical measurements

The juice pH was measured with the pH meter edge (Hanna® instruments). The soluble solids content was measured using a digital refractometer (model 300034, Sper Scientific). Total titratable acidity was measured with an 848 Titrino Plus Autotitrator (Ω Metrohm). The juice’s water activity (Aw) was measured with the Water Activity Meter Aqualab 4TE (Decagon). All physicochemical analyses were performed in triplicate.

Sample inoculation and HPP treatment

The HPP containers (66-mL PET bottles) were filled with the product leaving a maximum headspace of 5%. The volume of 0.5 mL of each pool, required for a target concentration of approximately 107 CFU/mL of juice, was inoculated into each container of product. The inoculation was performed in the BL2 safety cabinet and one sample was aseptically collected to determine the initial cell count (N0) in the product (standardized apple juice) as a positive control. DMDC was added immediately after the pathogens were inoculated. After sampling, containers were immediately sealed and repackaged independently into a plastic bag. Bags were sealed using a vacuum sealer and placed in a second plastic bag with chlorinated solution that was also sealed using the vacuum packaging machine and finally packaged in a third bag. Samples were placed in the HPP unit and subjected to the processing conditions (pressure and dwell time/holding time) indicated by experimental design (Tables 2 and 4). The pressure, dwell time, and water temperature were recorded. The HPP unit used is a Hiperbaric 55 L commercial processing unit. It has a water chiller to maintain the chamber water temperature during the HPP cycle; the apple juice was kept at a temperature of 8 °C. Once the HPP cycle was finished, the samples were immediately analyzed for the respective pathogens. Duplicate inoculated and HPP-treated samples were placed in a temperature-controlled incubator at 4 °C. These samples were enumerated for pathogen levels over a course of 30 days, to observe for any pathogen regrowth during that period.

Table 2.

Coded and actual values used in the central composite rotatable design (CCRD) for reducing foodborne pathogens inoculated in apple juice

| Variables | Code | − 1.68 | − 1 | 0 | + 1 | + 1.68 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (MPa) | x1 | 100 | 201 | 350 | 499 | 600 |

| Holding time (s) | x2 | 26 | 60 | 110 | 160 | 194 |

| DMDC (mg/L) | x3 | 116 | 143 | 183 | 223 | 250 |

− 1.68 (lower axial point), − 1 (lower level), 0 (central point), + 1 (upper level), + 1.68 (upper axial point)

α = (2n)1/4 = 1.68 where n is the number of variables

Table 4.

Matrix of the experimental design and responses obtained from the shelf stable apple juice inoculated with foodborne pathogen pools

| Trial | Variable | Response (log reduction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (MPa) | Dwell time (s) | DMDC (mg/L) | E. coli O157:H7 | S. enterica | L. monocytogenes | |

| 1 | 201 (− 1) | 60 (− 1) | 143 (− 1) | 7.4 | 4.8 | 6.4 |

| 2 | 499 (+ 1) | 60 (− 1) | 143 (− 1) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 3 | 201 (− 1) | 160 (+ 1) | 143 (− 1) | 7.4 | 5.4 | 6.4 |

| 4 | 499 (+ 1) | 160 (+ 1) | 143 (− 1) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 5 | 201 (− 1) | 60 (− 1) | 223 (+ 1) | 7.4 | 6.6 | 6.4 |

| 6 | 499 (+ 1) | 60 (− 1) | 223 (+ 1) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 7 | 201 (− 1) | 160 (+ 1) | 223 (+ 1) | 7.4 | 6.5 | 6.4 |

| 8 | 499 (+ 1) | 160 (+ 1) | 223 (+ 1) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 9 | 350 (0) | 110 (0) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 10 | 350 (0) | 110 (0) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 11 | 350 (0) | 110 (0) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 12 | 100 (− 1.68) | 110 (0) | 183 (0) | 5.4 | 5.4 | 6.4 |

| 13 | 600 (+ 1.68) | 110 (0) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 14 | 350 (0) | 26 (− 1.68) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 15 | 350 (0) | 194 (+ 1.68) | 183 (0) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 16 | 350 (0) | 110 (0) | 116 (− 1.68) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

| 17 | 350 (0) | 110 (0) | 250 (+ 1.68) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 |

− 1.68 (lower axial point), − 1 (lower level), 0 (central point), + 1 (upper level), + 1.68 (upper axial point)

α = (2n)1/4 = 1.68

Initial counts (log CFU/mL) — E. coli, 7.4; S. enterica, 7.2; L. monocytogenes, 6.4

Preparation of DMDC solution

DMDC (Velcorin™, 99.8%, Bayer Corp., Pittsburgh, PA) solution was freshly prepared by performing a 1:4 dilution in 100% (v/v) ethanol, and immediately added to 66 g of apple juice to obtain the final concentrations of 116, 143, 183, 223, and 250 mg/L (Table 2).

Colony enumeration of pathogens

Serial dilutions of each sample were done using 0.1% sterile peptone water. One (1) mL of each dilution was pour plated in Petri dishes with Violet Red Bile Agar (Alpha Biosciences™) for E. coli O157:H7, Bismuth Sulfite Agar (Criterion™) for S. enterica, and Oxford Listeria Agar Base (Alpha Biosciences™) for L. monocytogenes. Upon agar solidification, the Petri dishes were inverted and incubated for 24–48 h at 36 ± 1 °C. The colonies were enumerated using a Quebec colony counter, and the level of microbial reduction was determined.

Experimental design

Table 2 shows the levels used in the central composite rotatable design (CCRD), carried out according to Rodrigues and Iemma [10].

Data analysis

Data from the experimental design were processed through response surface methodology (RSM). The analysis of regression was firstly performed for both 1st (responses obtained from central points only) and 2nd (responses including axial points) orders, at 10% of significance. Due to the high variability of processes involving microorganisms, p values below 10% (p ≤ 0.1) were considered significant parameters, based on Rodrigues and Iemma [9]. Then, the mathematical model was reparameterized considering only the statistically significant coefficients . The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to ensure the model is statistically significant. If so, the response surface was built. Statistical tests were performed using the software Protimiza Experimental Design (http://experimental-design.protimiza.com.br).

Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the results from the physicochemical analysis of the food matrix used in this study.

Table 3.

Physicochemical parameters of the shelf-stable clarified (filtered) apple juice

| pH | Aw | Soluble solids (°Brix) | Titratable acidity (%malic acid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.76 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 12.5 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.00 |

Means from three measurements ± standard deviation

Basaran-Akgul et al. [5] reported pH values, soluble solids content, and titratable acidity for apple cider (unclarified apple juice) ranging from 3.24 to 3.91, 11.2 to 13.8 °Brix, and 0.295 to 0.650%, respectively. The results from this study are within the range of those reported previously.

Khan et al. [1] state that products with a high acid content, such as apple juice, are particularly favorable candidates for HPP technology. The pH of acidic solutions decreases as pressure increases and it has been estimated that, in apple juice, there is a pH drop of 0.2 unit per 100 MPa. When the pressure is released, the pH reverts to its original value. The pH and pressure can act synergistically leading to increased microbial inactivation [11].

A common element to all decontamination strategies by HPP is the need to account for the food matrices hosting these microorganisms. Food matrices are complex environments which may offer shelter to microorganisms, even under harsh treatment conditions [12].

The results from the combinations of different variables levels tested in this study are shown in Table 4. Only trials which achieved a ≥ 5-log reductions were considered effective, as required by the FDA for fruit and vegetable juices.

The results from Table 4 show that, regardless of the levels of variables, the combination of HPP and DMDC was highly effective on all pathogen reduction. Except for trial 1, the trinomial (201 MPa/60 s/143 mg/L DMDC) did not reach a reduction greater than 5-log cycles for S. enterica. The outcomes indicate the combination of relatively low pressure with DMDC can be successfully used as a means for reducing pathogens in apple juice. The results also suggest S. enterica is more resistant to the combination of HPP and DMDC than E. coli O157:H7 and L. monocytogenes. In general terms, Gram-positive bacteria, such as L. monocytogenes, tend to be more pressure resistant than Gram-negatives, and cocci are more resistant than rod-shaped bacteria. However, there are some exceptions. Certain strains of E. coli O157:H7 have been reported to be pressure resistant [11]. Samples, stored at 4 °C for 30 days, were plated; the pathogens did not regrow in apple juice over this time period.

Assatarakul [8] studied the effect of DMDC (ranging from 0 to 300 mg/L) on E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes, S. Enteritidis S. enteritidis (please delete), and S. aureus in fresh mandarin juice. The author reported that E. coli O157:H7 was the most sensitive pathogen, and the addition of DMDC can effectively aid in pathogen reduction.

Because there was no variation in the responses for L. monocytogenes (6.4-log reduction), and very little variation for E. coli O157:H7, neither the analysis of effects nor the analysis of variance was carried out. This finding indicates that, within the studied range, the variables had no effect on the aforementioned pathogen reduction. Further studies are warranted to exploit lower DMDC concentrations (< 116 mg/L).

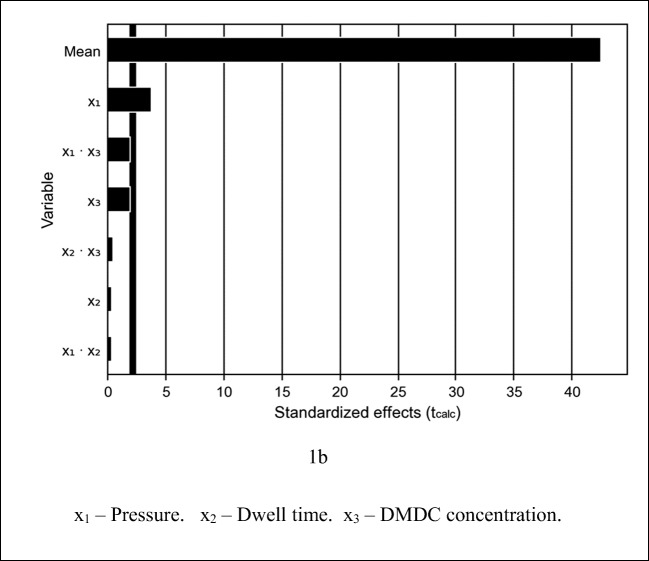

Figure 1 shows the diagram of effects (Pareto diagram) for S. enterica reduction.

Fig. 1.

Pareto diagram for reduction of S. enterica inoculated in apple juice (p ≤ 0.1). x1—pressure. x2—dwell time. x3—DMDC concentration

Figure 1 shows pressure (x1), DMDC concentration (x3), and the interaction between them (x1·x3), which had a significant effect (p ≤ 0.1) on S. enterica reduction. However, dwell time had no impact on S. enterica reduction. This is a very interesting finding, as it shows that the lowest level, in the studied range (26 to 194 s), can be applied to result in savings of energy, time, and financial resources.

Table 5 shows the analysis of variance (for S. enterica reduction.

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (p ≤ 0.1) for reduction of S. enterica inoculated in apple juice

| Variation source | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fcalc | Ftab | |||||

| 1st order | Regression | 5.9 | 3 | 1.97 | 11.59 | 3.07 |

| Residual | 1.2 | 7 | 0.17 | |||

| Total | 7.1 | 10 | ||||

| R2 | 0.83 | |||||

| 2nd order | Regression | 8.7 | 4 | 2.18 | 21.8 | 2.48 |

| Residual | 1.2 | 12 | 0.10 | |||

| Total | 9.9 | 16 | ||||

| R2 | 0.87 | |||||

The ANOVA shows the 2nd-order model (R2 = 0.87) better fitted to experimental data than the 1st-order model (R2 = 0.83). Additionally, Fcalc was approximately ninefold higher than Ftab as for the 2nd-order analysis, and fourfold higher, for 1st-order.

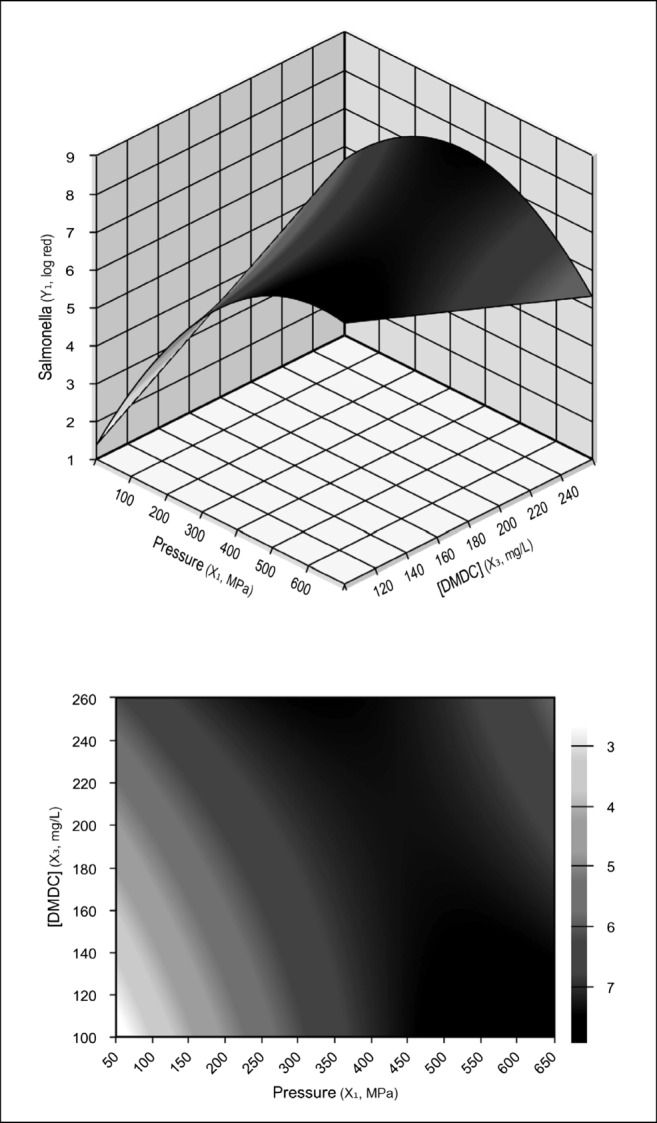

Figure 2 illustrates the response surface and the contour curves. Because the dwell time (x2) had no significant effect (p ≤ 0.1) on S. enterica reduction, this variable was not. shown in the coded predictive model (Eq. 1).

Fig. 2.

Response surface and contour curves in function of pressure and DMDC concentration for S. enterica reduction in apple juice

| 1 |

where Y1 is the log reduction of S. enterica, x1 is the pressure, and x3 is the DMDC concentration.

Analyzing the curve (Fig. 2), one can identify the existence of an optimal range for the pressure (400–600 MPa) and DMDC concentration (100–250 mg/L) for S. enterica reduction. This is of much greater interest than a simple point value, because it provides information about the “robustness” of the process, and most notably, it is the variation in pressure that may be permitted (± 100 MPa) around optimal value which still maintains the process under optimized conditions. This approach is fundamental to define and maintain the pressure sensor and controller levels, which directly affects viability and process implementation [10].

From Fig. 2, one can determine the pressure and DMDC concentration for achieving greater than 5-log reduction with S. enterica. The optimum condition (> 5-log cycles reduction) can be reached by combining relatively mild pressure (400 MPa) and DMDC concentration (120 mg/L), suggesting a synergistic effect between these two variables.

Coded Eq. 1 can be used to predict the number of log reductions of S. enterica by combining different pressures and DMDC concentrations, in the studied ranges. From another perspective, by setting the number of 5-log reduction in pathogens as target of processing, as required by the FDA, one can calculate the pressure and/or DMDC concentration to achieve that goal. The coded model (Eq. 1) is that whose regression coefficients are obtained from the matrix of coded variables (−α, − 1, 0, + 1, +α). In this way, to obtain a predicted value from the model, one must replace the values in the coded equation. Nevertheless, if using real values for the variables in the model, the predicted value may be incorrect and even absurd. Notably, equation contains only the statistically significant terms at 10%, as depicted in Pareto diagrams (Fig. 1). For practical purposes, it is desirable that the fitted model be as simple as possible and contain the smallest possible number of parameters without giving up the quality assured in the careful selection of the experimental design [10]. The models herein presented were reparameterized/reduced because the parameters with little or no influence, such as dwell time, on the outcome of the final fit were excluded.

Assatarakul [8] reported the effect of DMDC on degradation kinetics and inactivation of E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and S. enteritidis in fresh mandarin juice with and without heat. The results showed the addition of DMDC can effectively aid in pathogen reduction which leads to a decrease in heat exposure of the fresh mandarin juice, possibly enhancing its quality. Therefore, DMDC can potentially be used as an additional treatment or in combination with other treatments to improve the safety without significant effects on physical and chemical properties of mandarin juice.

Yu et al. [13] evaluated the effect of high pressure (200 MPa) and DMDC (250 mg/L) on microbial and nutrient qualities of mulberry juice. This combined treatment offered a useful alternative to conventional heat pasteurization for controlling microbial growth and significantly extending the juice’s shelf life.

Basaran-Akgul et al. [5] tested three strains of E. coli O157:H7 to assess the effectiveness of DMDC and SO2 in eight different unfiltered apple ciders. DMDC was extremely effective in extending the shelf life and enhancing the safety of fresh juices, not only due to its fungicidal activity but also due to its antibacterial activity against pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7. Two hours after DMDC addition, the authors obtained approximately 2- and 5-log cycles reduction for 125 and 250 mg/L DMDC, respectively.

Whitney et al. [14] investigated the effect of HPP in conjunction with DMDC on E. coli O157:H7 inoculated in shelf-stable apple juice. After inoculation, the juice was subjected to 550 MPa for 2 min at 6 °C. The most effective treatment was 125 mg/L of DMDC, which caused a 5-log reduction. The number of log reductions reached in this study (Table 4) was greater than those aforementioned.

According to Khan et al. [1], using combinations of these techniques could potentially save energy and improve food safety and quality. The combination of HPP and DMDC might reduce the cost of decontamination treatment and minimize the effect on quality, while extending the shelf life. Because almost all tested combinations (pressure × dwell time × DMDC concentration) gave pathogen reductions greater than 5 log, lower levels of pressure and DMDC might be investigated in further studies.

The results herein presented can be utilized by the apple juice industry for effective application of HPP combined with DMDC. Because the maintenance costs of HPP equipment increases with pressure, significant reductions in process pressure requirements are highly desirable. This study broadens the scope and possibilities for HPP parameters to provide improved knowledge in juice processing techniques where safety and quality are maintained at a potentially lower cost of production.

Conclusions

The combination of high pressure processing (HPP) and dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) was highly effective for the inactivation of L. monocytogenes, S. enterica, and E. coli O157:H7 pools in apple juice. Almost all tested combinations (pressure × dwell time × DMDC concentration) achieved greater than 5-log reductions in the pathogens of reference. The dwell time, in the studied range, did not have a significant effect on pathogen inactivation. The findings of this study showed that DMDC at low concentrations can be safely added to apple juice to reduce the parameters conventionally applied in HPP.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank LANXESS for donating the DMDC used in this project.

Funding information

This work was financially supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation/Brazil (FAPESP grant 2017/24172-6) and by the High Pressure Processing Validation Center at Cornell University/USA.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khan I, Tango CN, Miskeen S, Lee BH, Oh DH. Hurdle technology: a novel approach for enhanced food quality and safety - a review. Food Control. 2017;73:1426–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Shalini R. Effect of hurdle technology in food preservation: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(4):641–649. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.761594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasubramaniam VM, Farkas D. High-pressure food processing. Food Sci Technol Int. 2018;14(5):413–418. doi: 10.1177/1082013208098812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang HW, Wu SJ, Lu JK, Shyu YT, Wang CY. Current status and future trends of high-pressure processing in food industry. Food Control. 2017;72:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basaran-Akgul N, Churey JJ, Basaran P, Worobo RW. Inactivation of different strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in various apple ciders treated with dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) as an alternative method. Food Microbiol. 2009;26(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu YS, Wu JJ, Xiao GS, Xu YJ, Tang DB, Chen YL, Zhang YS. Combined effect of dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) and nisin on indigenous microorganisms of litchi juice and its microbial shelf life. J Food Sci. 2013;78(8):M1236–M1241. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Chen YL, Xu YJ, Wu JJ, Xiao GS, Zhang Y, Liu ZY. Effect of dimethyl dicarbonate as disinfectant on the quality of fresh-cut carrot (Daucus carota L.) J Food Process Preserv. 2013;37(5):751–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2012.00718.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assatarakul K (2017) Degradation kinetic models and inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms by dimethyl dicarbonate in fresh mandarin juice. J Food Saf 37(2)

- 9.Lindner JDD, Paggi D, Pinto VD, Soares D, Dolzan MD, Bevacqua D, Micke GA, Oliveira JV. A novel functional fruit/vegetable beverage for the elderly: development and evaluation of different preservation processes on functional and enriched components and microorganisms. J Food Res. 2017;6(4):17–33. doi: 10.5539/jfr.v6n4p17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigues MI, Iemma AF. Experimental design and process optimization. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usaga J, Worobo RW, Padilla-Zakour OI. Effect of acid adaptation and acid shock on thermal tolerance and survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O111 in apple juice. J Food Prot. 2014;77(10):1656–1663. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georget E, Sevenich R, Reineke K, Mathys A, Heinz V, Callanan M, Knorr D. Inactivation of microorganisms by high isostatic pressure processing in complex matrices: a review. Innovative Food Sci Emerging Technol. 2015;27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2014.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu YS, Wu JJ, Xu YJ, Xiao GS, Zou B. Effect of high pressure homogenization and dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) on microbial and physicochemical qualities of mulberry juice. J Food Sci. 2016;81(3):M702–M708. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitney BM, Williams RC, Eifert J, Marcy J. High pressures in combination with antimicrobials to reduce Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella agona in apple juice and orange juice. J Food Prot. 2008;71(4):820–824. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-71.4.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]