Abstract

Endophytes are microorganisms that form symbiotic relationships with their own host. Included in this group are the species Phyllosticta capitalensis, a group of fungi that include saprobes that produce bioactive metabolites. The present study aimed to identify the cultivable endophytic fungal microbiota present in healthy leaves of Tibouchina granulosa (Desr.) Cogn. (Melastomataceae) and investigate secondary metabolites produced by a strain of P. capitalensis and their effects against both Leishmania species and Trypanossoma cruzi. Identification of the strains was accomplished through multilocus sequencing analysis (MLSA), followed by phylogenetic analysis. The frequency of colonization was 73.66% and identified fungi belonged to the genus Diaporthe, Colletotrichum, Phyllosticta, Xylaria, Hypoxylon, Fusarium, Nigrospora, and Cercospora. A total of 18 compounds were identified by high-resolution mass spectrum analysis (UHPLC-HRMS), including fatty acids based on linoleic acid and derivatives, from P. capitalensis. Crude extracts had activity against Leishmania amazonensis, L. infantum, and Trypanosoma cruzi, with inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 17.2 μg/mL, 82.0 μg/mL, and 50.13 μg/mL, respectively. This is the first report of the production of these compounds by the endophytic P. capitalensis isolated from T. granulosa.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42770-019-00221-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Leishmania, Trypanossoma cruzi, Metabolomics, MLSA, Metabolic extract, OPLS-DA analyses

Introduction

Brazil is considered one of the richest countries in the world with respect to biodiversity, holding 15 to 20% of the animal species and the most diverse flora on Earth [1]. Living in this spectacular Atlantic rainforest environment is the species Tibouchina granulosa. Plants belonging to this genus are used both in traditional medicine as infusions applied to heal wounds [2] and as ornamental plants [3]. Some papers associating endophytes with the forest species have been investigated [4–6]. Few studies have been carried out associating microorganisms to the genus Tibouchina [7–12], but none of them addressing endophytic fungi.

The genus Phyllosticta Pers. ex Desm. (teleomorph Guignardia Viala and Ravaz) is a group of fungi that include saprobes and endophytes [13, 14]. P. capitalensis occurs as foliar endophytes in a wide range of plant hosts living in different parts of the world including South Africa, Japan, Thailand, India, and Brazil [15]. In the endophytic condition, this genus can provide resistance against pests and others phytopathogenic microorganisms, establishing a mutualistic/symbiotic relationship with host plants [16]. Fifty-one percent of the biologically active substances obtained from Phyllosticta were previously unknown [17], and the broad diversity and taxonomic spectrum exhibited by these fungi make them especially interesting for use in secondary metabolite screening programs. The genus Phyllosticta has been reported to produce novel bioactive metabolites with anti-cancer [18–22], mycoherbicide [18, 23], anti-cell proliferative [19], and antimicrobial activity [18, 24].

Leishmaniasis and Chagas diseases are complex, infectious, parasitic diseases caused by protozoa from Trypanosomatidae family. Both diseases are included in a group of neglected tropical diseases, although they are considered a public health threats affecting more than 12 million people worldwide, with 2–3 million cases of leishmaniasis and 6–7 million new cases of Chagas disease diagnosed each year [25].

There is little known about the endophytic diversity of Tibouchina granulosa or the biology and ecology of endophytic Phyllosticta, except that pharmaceutically important secondary metabolites are produced by some isolates. The objective of this study was to identify culturable endophytic isolates from T. granulosa, characterize the secondary metabolites produced by the strain Tg06 (P. capitalensis) by UHPLC-HRMS, and evaluate biological activity of extracts against both Leishmania species and Trypanossoma cruzi.

Materials and methods

Endophytic fungi

The leaves of T. granulosa were collected in the city of Apucarana, in the state of Paraná, Brazil (23°33'S, 51°26'W) during the month of July 2016. Precipitation, mean temperature, and relative humidity in the month of collection were 58.6 mm, 17.23 °C, and 65.79%.

For the isolation of fungi, the leaves of T. granulosa were surface sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol (1 min), 3% sodium hypochlorite (4 min), 70% ethanol (30 s), and then washed twice in previously autoclaved distilled water. The efficacy of this method was verified by inoculating 100 μL of the final rinse water onto Petri dishes containing Potato, Dextrose, Agar (BDA) medium (HiMedia®, Mumbai, India) pH 6.6.

Then, the disinfected leaves were cut into small fragments of about 5 mm by 2 mm. Subsequently, five leaf fragments were arranged per petri dish containing BDA medium plus tetracycline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (50 μg/mL in 50% ethanol), making a total of 100 plaques. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for 7 days. The frequency of colonization was determined by [26].

In the purification process, isolated fungi were transferred to Petri dishes with BDA and grown for 7 days. Then, monosporal colonies were obtained in macerated fragments (2 mm2) in 1 mL of 0.01% Tween 80 aqueous solution, and an aliquot of 100 μL of solution were used to inoculate Petri dishes containing BDA medium, and they were incubated for 24 h. The colonies were then transferred to BDA plates and incubated for 7 days. The endophytic fungi were stored in the collection of microorganisms at the Laboratorio de Biotecnologia Microbiana—LBIOMIC, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, and preserved using Castellani method [27].

The choice of using strain Tg06 for metabolite analysis and bioassays was based on a previous antagonism test (data not shown) in which Tg06 was the only one endophyte that displayed distance inhibition against phytopathogenic fungi, demonstrating potential to produce bioactive secondary metabolites.

Multilocus sequences analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted according to previously described methods [28, 29]. Primers EF1-728F (5′-CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG-3′) and EF1-986R (5′-TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC-3′) [30] were used to amplify part of gene encoding translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1), and ITS-1 (5′- TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) [31] and ITS-4 (5′TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) primers were used to amplify the rRNA region of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2. For the amplification of the Tubulin gene (TUB), the primers T1 (5′-AACATGCGTGAGATTGTAAGT-3′) and Bt2b (5′-ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC-3′) were used. Amplification products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5%), and subsequently purified with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) and exonuclease I (EXO). Reactions were performed using 8-μL PCR product, 0.5-μL EXO (10 U/μL), and 1-μL SAP (1 U/μL) and incubated in a thermocycler for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by 15 min at 80 °C and were stored at 4 °C. Samples were sequenced by ACTGene Análises Moleculares Ltd. (Ludwigbiotec).

Sequences were then analyzed and edited using the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor v. 7.2.2 software. The strain genera was identified based on homology with other sequences deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the BLASTn, and limiting the alignment with type strains sequences. Aiming to identify the species of the strain, other sequences of the same genera were also selected for phylogenetic analysis based on available studies within the TreeBASE database (Studies S14476 and S1560; www.treebase.org). Sequences were then rescued and aligned using the online interface MAFFT [32] (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/). After alignment, the multigene assembly of sequences was performed using the SequenceMatrix software (http://gaurav.github.io/taxondna/) [33].

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the MrModelTest v. 2.3 software and was based on the maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference [34] for the choice of the best evolutionary model. The software MrBayes v. 3.2.5 [35] was used to construct the phylogenetic tree, considering the parameters generated by MrModelTest, with MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) lasting until the average standard deviation of split frequencies came below 0.01. The tree was edited using the software FigTree v. 1.4.2 [36]. The obtained strains were deposited in the GenBank access number MN148263–MN148291 and MN151267–MN151306.

Obtaining crude metabolic extracts

Fungi were grown on potato dextrose broth (Himedia, Bombay, India) with three discs (6 mm in diameter) inoculating 500-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 250-mL broth and incubating at 28 °C for 30 days. Mycelium was separated from broth by filtration using gauze, cotton, and a funnel. The liquid extraction was performed using ethyl acetate in a ratio of 1:5 (ethyl acetate: broth) in a separation funnel. This step was repeated three times. The solvent present was collected and evaporated using a rotary evaporator (Tecnal TE-210) at 37 °C.

Metabolite identification

Liquid chromatography

An Acquity I-Class UPLC (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) was used with an ACQUITY UPLC® HSS C18 SB column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8-μm particle size, Waters Corporation, Milford, USA), operating at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and at 45 °C. The chromatographic separation was performed in gradient mode using a mobile phase system consisting of two solvents, A and B. Solvent A was 0.1% ammonium hydroxide in Milli-Q water and solvent B was 0.1% ammonium hydroxide in acetonitrile. The gradient started with 93% A and 7% B, changing linearly to 5% A and 95% B in 20 min where it was held 3 min before returning to the initial composition for 4 min. The injection volume was 20 μL.

Mass spectrometry

The inlet system was coupled to a hybrid quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer, QTof HRMS (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA), controlled by using the MassLynx 4.1 software. The conditions were electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode (ESI-) with capillary voltage set to 2.5 kV, cone voltage of 30 V, and source temperature of 150 °C. The desolvation gas was nitrogen, with flow of 700 L/h and temperature of 400 °C. Data was acquired from m/z 100 to 1000 in MS mode. Leucine-enkephalin (Waters Corporation, USA), C28H37N5O7 ([M-H]− of m/z 554.2771), was used as lock mass reference at a concentration of 0.2 ng/L with a flow rate of 10 μL/min.

Data processing and statistical analyses

The EZinfo software (Umetrics, Sweden) was used to process data for peak detection, multivariate analysis, and identification. The MassBank of North America (http://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu) and the LIPID MAPS Structure Database (lipidmaps.org) were used to evaluate molecular possibilities for the extract composition. The precursor mass error ≤ 10 ppm was used for molecules identification. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Projection on Latent Structure-discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) were generated by using the EZinfo software (Umetrics, Sweden). Other parameters such bibliographic registry of the occurrence of the molecules were also considered for disambiguation.

Analysis of anti-protozoal activity

Compound

The crude extract was diluted in DMSO to obtain a stock concentration (10.000 μg/mL). The concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% in the experiments.

Culture of parasites and mammalian cells

Promastigote forms of Leishmania amazonensis (strain WHOM/BR/75/JOSEFA) and Leishmania infantum Nicolle (strain zymodeme MOM-1) were cultured in Warren culture medium (containing Brain Heart Infusion, hemin, and folic acid; pH 7.2) and RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640; pH 7.4), respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal serum (SFB) and kept in an oven at 26 °C. Epimastigote forms of T. cruzi (strain Y) were grown in LIT (Liver Infusion Tryptose; pH 7.4) medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and kept in an oven at 28 °C. Mammalian cells from the LLCMK2 (Macaca mulata kidney epithelial cell) and L929 (murine fibroblast) lineage were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle; pH 7.4) culture medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and maintained in an oven at 37 °C and atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Antiproliferative assay

Promastigote forms of L. amazonensis and L. infantum (1 × 106 parasites/mL) in exponential growth phase were treated (or not) using different concentrations of compounds in a 96-well plate for 72 h. After treatment, evaluation of cell growth was determined by counting in Neubauer’s chamber under an optical microscope. Epimastigote forms of T. cruzi (1 × 106 parasites/mL) in the exponential growth phase were treated (or not) using different concentrations of each compound in a 96-well plate for 96 h. After treatment, evaluation of cell growth was determined by counting in Neubauer’s chamber under an optical microscope. The inhibitory concentration for 50% of parasites was calculated in comparison with the untreated controls.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells of lineage L929 and LLCMK2 (2.5 × 105 cells/mL) were grown in 96-well plate for 24 h, in order to obtain a confluent layer of cells. Then, the cells were treated (or not) at different concentrations of the crude extract at 72 h and 96 h. After treatment, tretazolium salt (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; 2 mg/mL in PBS)) were added to the cells and incubated for 4 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed and DMSO was added to solubilize the formazan crystals, and absorbance was taken at 492 nm using spectrophotometer for microplates (Bio Tek-Power Wave XS). Through the absorbance, the cytotoxic concentration for 50% of the cells (CC50) was calculated in comparison with the untreated controls. The selectivity index (SI) against parasite forms was calculated using the following formula: IS = CC50/IC50.

Results

Isolation

The isolation frequency was 73.66% for a total of 500-leaf fragments. The 30 fungi isolated were categorized into morphogroups according to the characteristics of the colony, with 30 fungi selected for identification.

Multilocus sequences analyses

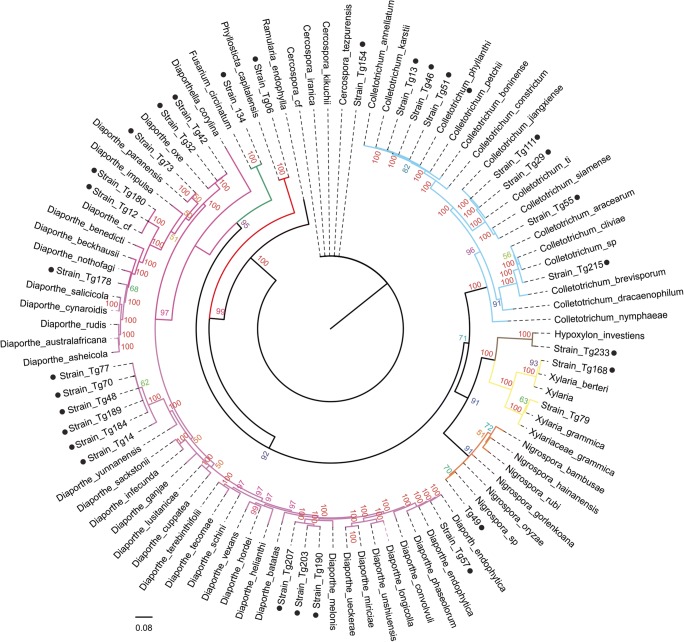

It was possible to identify molecularly 30 strains, divided into 8 genera (Fig. 1; Suppl. Fig. 1S). The MLSA using the combination of the ITS, EF1, and TUB genes revealed that 53.3% of the isolates submitted to be identified belong to the genus Diaporthe (7 genealogical groups), 23.3% belong to the genus Colletotrichum (4 genealogical groups), and 23.3% are divided among other genera (7 genealogical groups) (Fig. 1; Table 1; Suppl. Fig. 1S–4S).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of endophytic fungi isolated from T. granulosa defined by Bayesian analysis. Standard deviation of 0.01 for 100,000 generations

Table 1.

Endophytic fungi isolated from healthy T. granulosa leaves and access numbers searched in GenBank for identification

| N° sp | Strain | Identification | Isolate | Access on GenBank* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | TUB | TEF-1 | ||||

| 1 | Tg 06 | Phyllosticta capitalensis | CBS 100175 CBS 123404 CBS 119720 | FJ538320.1 (97.5) FJ538333.1 (97.5) KF206178.1 (97.5) | - | FJ538378.1 (100) FJ538391.1 (98.9) FJ538398.1 (98.4) |

| 2 | Tg 012 | Diaporthe cf. hevea 1 | CBS 852.97 | KC343116.1 (99.2) | KC344084.1 (98.7) | KC343842.1 (99) |

| 3 | Tg 013 | Colletotrichum karstii | CMM 3797 | KC702990.1 (99.6) | KC992339.1 (98) | N/A |

| 4 | Tg 014 | Diaporthe sp | CBS 114015 | KC343010.1 (95.6) | KR936132.1 (87.3) | - |

| 5 | Tg 029 | Colletotrichum jiangxiense | LF 684 LF 687 | KJ955198.1 (98.2) KJ955201.1 (98.2) | KJ955345.1 (99) KJ955348.1 (99) | N/A |

| 6 | Tg 032 | Diaporthe oxe | CBS 133186; LGMF915; CBS 133187 | KC343164.1 (99.2) KC343166.1 (99.2) KC343165. 1 (98.1) | KC344132.1(99.1) KC344134.1 (98.1) KC344133.1 (97.3) | KC343890.1 (100) KC343892.1 (100) KC343891.1 (100) |

| 7 | Tg 042 | Diaporthe oxe | CBS 133186; LGMF915; CBS 133188 | KC343164.1 (99.2) KC343166.1 (99.2) KC343165.1 (99.2) | KC344132.1 (98.4) KC344134.1 (97.3) KC344133.1 (97.7) | KC343890.1 (100) KC343892.1 (100) KC343891.1 (100) |

| 8 | Tg 046 | Colletotrichum karsii | CBS 128500 | JQ005202.1 (99.7) | JQ005636.1 (100) | N/A |

| 9 | Tg 048 | Diaporthe sp | BRIP 45669 | NR147537.1 (96.6) | - | KT459451.1 (87.4) |

| 10 | Tg 049 | Nigrospora sp. | P39E2 | JN207335.1 (99.7) | - | - |

| 11 | Tg 051 | Colletotrichum karstii | CBS 128500 | JQ005202.1 (99.7) | JQ005636.1 (100) | N/A |

| 12 | Tg 055 | Colletotrichum siamense | BPDI2 | FJ972613.1 (97.6) | FJ907438.1 (98.5) | N/A |

| 13 | Tg 057 | Diaporthe endophytica | LGMF948 | KC343072.1 (99.6) | KC344040.1 (97.5) | KC343798.1 (100) |

| 14 | Tg 070 | Diaporthe sp | BRIP57892a | NR147534.1 (95.5) | - | JQ954663.1 (85.3) |

| 15 | Tg 073 | Diaporthe paranaensis | CBS 133184 | KC343171.1 (97.5) | KC344139.1 (98.2) | KC343897.1 (97) |

| 16 | Tg 077 | Diaporthe sp | CBS 122.21 | NR152456.1 (96.7) | KP189344.1 (97.3) | JQ954663.1 (85.2) |

| 17 | Tg 079 | Xylaria grammica | 5151 | JQ862665.1 (96.3) | JX868535.1 (92.1) | N/A |

| 18 | Tg 111 | Colletotrichum jiangxiense | LF 684 LF 687 | KJ955198.1 (98.6) KJ955201.1 (98.6) | KJ955345.1 (100) KJ955348.1 (100) | N/A |

| 19 | Tg 134 | Fusarium circinatum | CBS 405.97 | KC464617.1 (99.7) | KM232080.1 (99) | KM231943.1 (97.4) |

| 20 | Tg 154 | Cercospora sp | CPC24809 | NR147294.1 (97) | - | JX143412.1 (100) |

| 21 | Tg 168 | Xylaria berteroi | YMJ 90112623 | KC473562.1 (100) | AY951763.1 (98.1) | KC465407.1 (99) |

| 22 | Tg 178 | Diaporthe sp | CBS122676 | NR111846.1 (96.8) | KC344009.1 (93.9) | JX862537.1 (89.2) |

| 23 | Tg 180 | Diaporthe cf. hevea 1 | CBS 852.97 | KC343116.1 (99.1) | KC344084.1 (99.6) | KC343842.1 (98.9) |

| 24 | Tg 184 | Diaporthe sp | BRIP57892a | KJ197276 (97.9) | KR936132.1 (92.7) | JQ972716.1 (85.5) |

| 25 | Tg 189 | Diaporthe sp | BRIP 57892a | NR147534.1 (96) KX197977.1 (100) | KR936132.1 (92.2) | KJ197241.1 (90.5) |

| 26 | Tg 190 | Diaporthe melonis | CBS507.78 CBS435.87 FAU640 CMT41 | NR103700.1 (97.4) FJ889447.1 (97.4) | KC344020.1 (95.6) | KJ590764.1 (98.3) |

| 27 | Tg 203 | Diaporthe melonis | CBS507.78 CBS435.87 FAU640 CMT41- | NR103700.1 (95) FJ889447.1 (95) | KC344038.1 (95.1) | KJ590764.1 (96.7) |

| 28 | Tg 207 | Diaporthe melonis | CBS507.78 CBS435.87 FAU640 CMT41 | NR103700.1 (96.6) FJ889447.1 (96.5) | KC344084.1 (82.5) | KJ590764.1 (96.1) |

| 29 | Tg 215 | Colletotrichum sp | BCC38876 | NR111637.1 (98) | KP890114.1 (98.37) | N/A |

| 30 | Tg 233 | Hypoxylon investiens | STMA 14058 | KU604568.1 (96.1) | KU159528.1 (99.6) | N/A |

*Values indicate percent sequence identity compared with GenBank

-Gene not sequenced

ITS, internal spacer regions transcribed from the nrDNA and interconnecting the 5.8 SnrDNA; TUB, partial beta-tubulin gene; TEF1, partial translation stretching factor 1-alpha gene; N/A, gene not located in the database for the genre in question; CBS, Fungi Biodiversity Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands; LGMF, cultural heritage of the Laboratory of Genetics of Microorganisms of the Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil; LF, Fang Liu’s work collection, housed in CAS, China; Collection CMM culture of phytopathogenic fungi “Prof. Maria Menezes,” Recife, Brazil; STMA, HZI culture collection, Helmholtz Center for Infection Research, Braunschweig, Germany

Details of Tg06 (Phyllosticta capitalensis)

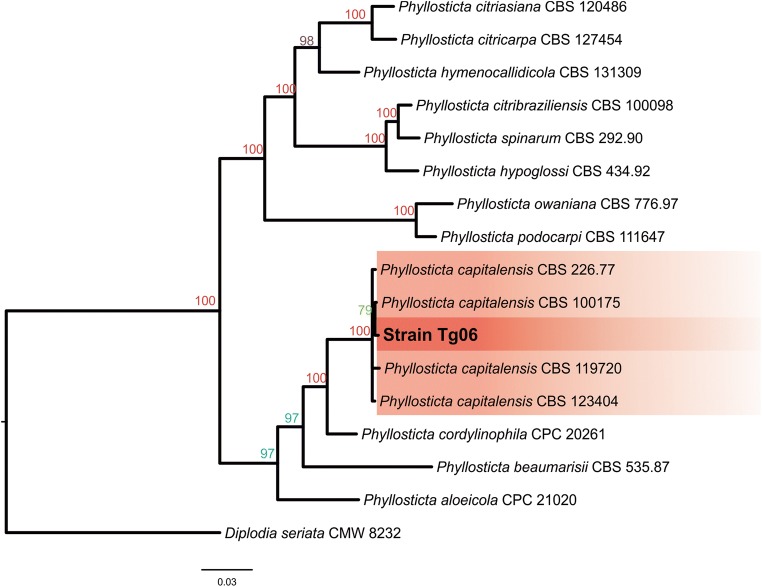

The ITS and TEF sequences of strain Tg06 were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers MG214956 and MG256493, respectively. The phylogeny was deposited on Treebase with study number S-21741. The strains used to phylogenetic analyses in this work are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Phyllosticta strains investigated in this phylogenetic study

| Specie | Isolate | Host | Country | ITS | TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. capitalensis | CBS 123404 | Musa paradisiaca | Thailand | FJ538333.1 | FJ538391.1 |

| P. capitalensis | CBS100175 | Citrus sp. | Brazil: São Paulo | FJ538320.1 | FJ538378.1 |

| P. capitalensis | CBS 119720 | Musa sp. | USA | KF206178.1 | FJ538398.1 |

| P. capitalensis | CBS 226.77 | Paphiopedilum callosum | Germany | FJ538336.1 | FJ538394.1 |

| P. citrisiana | CBS 120486 | Citrus maxima | Thailand | FJ538360.1 | FJ538418.1 |

| P. citricarpa | CBS 127454 | Citrus limon | Australia | JF343583.1 | JF343604.1 |

| P. hymenocallidicola | CBS 131309 | Hymenocallis littoralis | Australia | JQ044423.1 | KF289211.1 |

| P. citribraziliensis | CBS 100098 | Citrus sp. | Brazil | FJ538352.1 | FJ538410.1 |

| P. spinarum | CBS 292.90 | Chamaecyparis pisifera | France | JF343585.1 | JF343606.1 |

| P. hypoglossi | CBS 434.92 | Ruscus aculeatus | Italy | FJ538367.1 | FJ538425.1 |

| P. owaniana | CBS 776.97 | Brabejum stellatifolium | South Africa | FJ538368.2 | FJ538426.1 |

| P. podocarpi | CBS 111647 | Podocarpus lanceolata | South Africa | KF289232.1 | KF766217.1 |

| P. cordylinophila | CPC 202.61 | Cordyline fruticosa | Thailand | KF170288.1 | KF289171.1 |

| P. beaumarisii | CBS 535.87 | Muehlenbekia adpressa | Australia | KF766212.1 | KF289170.1 |

| P. aloeicola | CPC 210.20 | Aloe ferox | South Africa | KR183768.1 | KF289193.1 |

| Diplodia seriata* | CMW8232 | Conifers | South Africa | AY972105.1 | DQ280419.1 |

CPC, Culture collection of P.W. Crous; CBS, CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands; ITS, Internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 together with 5.8S nrDNA; TEF1, partial translation elongation factor 1-α gene

*Sequences used as outgroup

Based on the ITS and TEF1 homologies on GenBank, the strain Tg06 was closely related to P. capitalensis CBS 100175 (identities 529/549 (96%), gaps = 0/549). The ITS and TEF1 sequence alignments to other P. capitalensis strains were strain CBS 123404 (identities = 544/567(96%), gaps 1/567(0%); identities = 194/196(99%), gaps 0/196(0%)), CBS 119720 (identities = 529/549 (96%), gaps 0/549; identities = 193/196(98%), 0/196(0%)), and CBS 22677 (identities = 528/549(96%), gaps 0/549; identities = 195/196(99%), gaps 1/196 (0%)) (Table 3). The strains CBS 119720, CBS 226.77, and CBS 123404, although named G. mangiferae in GenBank, in this work were named using the nomenclature P. capitalensis.

Table 3.

Sequences deposited in the GenBank database with higher identity to sequenced genes of the Tg06 endophytic strain (Phyllosticta capitalensis)

| Specie | Strain | ITS | TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phyllosticta capitalensis | CBS 123404 | 96% | 99% |

| Phyllosticta capitalensis | CBS 100175 | 96% | 100% |

| Phyllosticta capitalensis | CBS 119720 | 96% | 98% |

| Phyllosticta capitalensis | CBS 226.77 | 96% | 99% |

In phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2, Tab. 3), a clade of P. capitalensis sequences was presented as 100% of Bayesian probability. The sequences used for the comparison of these sequences are strains that were previously confirmed using molecular taxonomy and micro- and macro-morphological characters. These data contribute to confirming the identity of the Tg06 strain as belonging to the P. capitalensis species.

Fig. 2.

Cladogram results of the Bayesian analysis with the combined alignment of two genes (ITS, EF1). Bayesian probabilities are shown on the nodes between each individual. The sequence of Diplodia seriata CMW 8232 was used as outgroup. Standard deviation (SD) 0.01/40.000 generations

UHPLC-HRMS of the extract

Figure 3 is a representative chromatogram of base peak intensity (BPI) generated by UHPLC-HRMS from an EtOAc extract. Performing a visual inspection of this chromatogram based on exact masses, we were able to detect possible constituents (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

UPLC-Q-TOF/MS BPI chromatogram in mode negative from EtOAc extract obtained from the endophytic fungus Phyllosticta capitalensis isolated from T. granulosa

Table 4.

Results of high resolution UHPLC-HRMS mass spectrum analysis

| Compounds | Adducts | Formula | Mass error (ppm) | m/z | Retention time (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allantoate | [M-H]− | C4H8N4O4 | 0.0 | 175.0546 | 0.63 |

| 2 | 5-methoxy-3-indole acetic acid (IAA) | [M-H]− | C11H11NO3 | 1.46 | 204.0742 | 0.86 |

| 3 | Cinnamoylglycine | [M-H]− | C11H11NO3 | 1.46 | 204.0742 | 0.86 |

| 4 | N-acetylphenylalanine | [M-H]− | C11H13NO3 | −3.38 | 206.0888 | 0.86 |

| 5 | Metaxalone | [M-H]− | C12H15NO3 | 8.14 | 220.107 | 1.65 |

| 6 | Isofraxidin | [M-H]− | C11H10O5 | −4.50 | 221.0518 | 1.32 |

| 7 | N-(3-Oxobutyl)-tyrosine | [M-H]− | C13H17NO4 | 0.00 | 250.1215 | 1.65 |

| 8 | Linoleic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 9 | 9Z, 11E-linoleic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 10 | (9Z,12Z)-octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5,63 |

| 11 | 9Z,12Z-linoleic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 12 | Chaulmoogric acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5,63 |

| 13 | (9Z, 12Z)-octadecadienoate | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 14 | 9E, 11E-linoleic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 15 | 10E, 12Z-linoleic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 16 | Linoelaidic acid | [M-H]− | C18H32O2 | 7.13 | 279.2422 | 5.63 |

| 17 | Octadecanedioic acid | [M-H]− | C18H34O4 | 0.00 | 313.2439 | 4.17 |

| 18 | 9,10-DiHOME | [M-H]− | C18H34O4 | 0.00 | 313.2439 | 4.17 |

Table 4 shows the ions found by UHPLC-HRMS analysis from EtOAc extracts obtained from strain P. capitalensis (Tg06). Molecular masses of the ionized compounds ranged from 100 to 1000 in negative mode. Five compounds with the CHNO formula and fourteen compounds with CHO formula were proposed. Chemical identification was carried out, comparing exact masses obtained to a very large databank of metabolites and lipids. The range of possibilities is very large since EtOAc extracts may come in contact with both natural organic matter and anthropic organic matter. Thus, a specific database for ion identification was used, where the main factors were low mass error (ppm), high isotope similarity, and the probability of ionization by ESI. As there is no specific data bank of molecules for extract from endophytic fungi analysis, metabolomic (http://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu) and lipidomic (lipidmaps.org) data banks were used to evaluate molecular possibilities for compounds identified by screening. Initially 62 possibilities were identified using these databases. After excluding identifications with mass errors higher than 10 ppm and finally excluding molecules, 18 possible molecules remained (Table 4).

All the molecular formulas considered were in good agreement with the parameters of isotopic patterning, so all high-resolution mass spectrometric chromatograms of EtOAc extracts were evaluated by PCA analysis, using the culture medium extract without fungal inoculum as a blank (Suppl. Fig. 5S–7S).

Anti-protozoal activity

The crude extract of P. capitalensis showed antiparasitic activity, with an inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 17.2, 82.0 and 50.13 μg/mL when testing L. amazonensis, L. infantum, and T. cruzi, respectively. However, the crude extract also showed toxicity to fibroblasts, with a CC50 value of 135.95 μg/mL. The selectivity index (SI) values for L. amazonensis and L. infantum were 7.9 and 1.6, respectively. For T. cruzi, the crude extract showed similar toxicity to both host cells (epitelial LLCMK2) and the parasite, with a SI value of 1.12 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Antiprotozoal activity (IC50) and toxicity to mammalian cells (SI) of the crude extract from the fungus, Phyllosticta capitalensis

| Cells | IC50 (μg/mL) | SI(a,b,c) |

|---|---|---|

| Leishmania amazonensis | 17.2 ± 0.5 | 7.9(a) |

| Leishmania infantum | 82 ± 5.7 | 1.6(b) |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | 50.1 ± 12.7 | 1.1(c) |

| Fibroblast L929 | 135.9 ± 29.1 | - |

| Epitelial LLCMK2 | 55.9 ± 8.3 | - |

IC50, inhibitory concentration for 50% of the parasites; CC50, cytotoxic concentration for 50% of mammalian cells; SI, selectivity index; SI(a), selectivity index in promastigote forms of Leishmania amazonensis (CC50 in L929/IC50); SI(b), selectivity index in promastigote forms of Leishmania infantum (CC50 in L929/IC50); SI(c), selectivity index in epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi (CC50 in LLCMK2/IC50)

Discussion

The frequency of isolation (FI) can be variable as a result of numerous factors, such climatic conditions of the collection site, geographic location, age, and part of the plants used [37]. Other papers have reported similar FI values from leaves of other Angiospermae families [5, 38]. Some factors interfere qualitatively and quantitatively in the biodiversity of endophytes found in a plant. These factors include the age of the plant, the tissue or organ, the physiological condition of the host, environmental conditions, and the geographic distribution [39, 40].

The study of molecular taxonomy revealed that the genus Diaporthe (anamorph: Phomopsis) are predominant in the leaf tissues of T. granulosa (51.72% of the isolates submitted to identification). As observed in this study, the genus Diaporthe can also be found in other plants [41, 42]. This can be explained by this genre being adapted to different environments and conditions, having a wide distribution around the world [43–45].

Species of the genus Colletotrichum are among the most common pathogens of terrestrial plants. They were included in the list of the 10 most important plant pathogenic fungi in the world based on economic importance [46, 47]. It is considered an important and widespread genus, being recorded in approximately 2200 species of plants [48]. In general, Colletotrichum species have different lifestyles that can be categorized as necrotrophic, hemibiotrophic, latent or quiescent, and endophytic, of which hemibiotrophy is the most common [49, 50].

P. capitalensis has been repeatedly isolated worldwide from healthy plant tissues as an endophyte and rarely from leaf spots as a pathogen. Further, it has been recorded from almost 70 plant families [24], but we did not identify it from the family Melastomataceae.

In the microscopic optical analysis of this study, it was not possible to observe reproductive structures. This is due to the fact that the conidia of Phyllosticta rarely germinate in culture, and thus, with many species it is impossible to obtain single spore cultures [51]. P. capitalensis is a quick growing species; in this study, the colony covered 3.8 cm of Petri in 10 days. Other species grow more slowly, e.g., P. yuccae reaches 3–5-cm diameter in 15 days [52], while growth of P. vaccinii can be as low as 0.4 mm/day [24].

Phyllosticta species may be associated with a “Guignardia-like” sexual state and has been studied by several authors [13, 24, 53, 54]. However, there is some confusion regarding the identification and naming of the P. capitalensis sexual morph. Okane et al. [54] stated that the teleomorph of P. capitalensis differed morphologically from G. mangiferae. This occurs mainly because this genus had a broad inclusion, and any fungus with unicellular ascospores, any type of asci, and simple ascomata were placed in this genus [55].

To solve this problem, after the deletion of art. 59 from the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants, valid since January 2013, the asexual and sexual names of fungi received equal status and binomial nomenclature was replaced by a single name based on priority. Since the genus Phyllosticta was introduced by Persoon in 1818 (a much older name than Guignardia introduced by Viala and Ravaz in 1892), Phyllosticta has been currently used as the legitimate genus name [56].

Some secondary metabolites have been isolated from the genus Phyllosticta, including Brefeldin [57], heptelidic acid, hydroheptelidic [58] melanin [46], phyllostin, phyllostoxin [18], tauranine, phyllospinarone [19], taxol [20] phyllostictine [22], and guignardone B [59].

The selection of ions on mass spectrometry was mediated by multivariated statistical approaches as PCA and OPLS-DA. The PCA provide a qualitative data about the distribution of samples [60]. In our results, it identifies the differences in extracts compared with broth. Therefore, it can help us to identify differential molecules produced by fungus, that was absent in broth. In addition, the OPLS-DA together with S-Plot provided quantitative data of most important ions on the samples [61]. More details about these analyses can be seen in the supplementary materials.

The 27 ions observed on S-plot with most responsible for distinguishing the EtOAc extracts of culture medium were submitted to databases. Thus, we noted compounds such as metabolites of purine metabolism, coumarin, amino acids, mephenoxalone nuclei, and fatty acids [60–66]. Since we used high resolution for identification, isomers with the same molecular formula may have been identified as the same molecule.

The 18 compounds found in this study were placed into 6 groups: ureides (allantoate), coumarins (isofraxidin), indolacetic acid (IAA) (5-Methoxy-3-indole acetic acid and Cinnamoylglycine), aminoacids (N-(3-Oxobutyl)-tyrosine and N-acetylphenylalanine), linoleic acid and derivatives (linoleic acid, 9Z, 11E linoleic acid, (9Z, 12Z)-octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid, 9Z, 12Z-linoleic acid, chaulmoogric acid, (9Z, 12Z)-octadecadienoate, 9E, 11E-linoleic acid 10E, 12Z-linoleic acid, linoelaidic acid, octadecanedioic acid, 9,10-DiHOME), and Metaxalone.

Different classes of fungal metabolites have been reported for their antileishmanial potential. Ponti et al. [67] isolated extracts of Arthrinium, Cochliobolus, Colletotrichum, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Gibberella which displayed inhibition against L. amazonensis with IC50 values ranging from 4.60 to 24.40 μg/ml. Other papers report similar results [68–70].

Allantoate is an intermediate of adenine and guanine degradation and is grouped with ureides [71]. Tewari and collaborators [72] demonstrated that ureides can be active against both promastigote and amastigote forms of Leishmania at 50 μg/mL or 25 μg/mL concentrations. The compound has a part of some physiological process of the fungus P. capitalensis.

The compound isofraxidin belongs to a family of coumarins and their derivatives. The coumarins are a group of natural compounds found in diverse plant species. Hydroxycoumarins have various bioactivities and contribute to the persistence of plants as defense compounds against phytopathogens, the response to abiotic stresses, the regulation of oxidative stress, and possibly, hormonal regulation [73]. Brenzan and collaborators [74] evaluated coumarin-type compounds against L. amazonensis and showed that they had significant activity against promastigote and amastigote forms, with IC50 at concentrations between 3.0 and 0.88 μg/ml. The authors observed significant changes such as mitochondrial swelling with concentric membranes in the mitochondrial matrix and intense exocytic activity in the region of the flagellar pocket. Other alterations included the appearance of binucleate cells and multiple cytoplasmic vacuolization.

The compounds N-(3-Oxobutyl)-tyrosine and N-acetylphenylalanine, or afalanine, are aromatic amino acids derived from chorismic acid [75]. The N-acetylphenylalanine is used as an antidepressant drug and in combination with antibiotics to prevent kidney damage [76]. Tawfike and collaborators [65] isolated this compound from the endophytic fungus Curvalaria sp and tested the anticancer activity of the compound.

Linoleic acid is an essential fatty acid that is of growing interest in the pharmaceutical industry as a precursor of prostaglandin E1. This prostaglandin has been clinically shown to be able to reduce inflammation, including that of rheumatic origin, dilate veins, reduce blood pressure, reduce cholesterol levels and thrombus formation, and relieve depression by acting as a modulator of the nervous system [77]. This fatty acid has been isolated from other endophytes as reported by Carvalho and collaborators [69]. This is the first report of the production of linoleic acid by the endophytic P. capitalensis. The compounds octadecanedioic acid and 9.10 DiHome proposed in this study are derivatives of linoleic acid.

Metaxalone is a skeletal muscle relaxant with low toxicity and can be used along with rest, physical therapy, and other measures, for the relief of discomforts associated with acute, painful, musculoskeletal conditions [78]. We have not found studies that indicate the natural production of metaxalone from any source.

The present results suggest that P. capitalensis can also produce antiparasitic compounds making them potential producers of trypanocidal and leishmanicidal drugs. It may be that a crude compound from P. capitalensis inhibits the enzymatic activation of gGAPDH (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) in T. cruzi or the catalytic activity of APRT (Adenine phosphorybosiltransferase) in Leishmania as suggested by Guimarães [79, 77]. It also may inhibit trypanothione reductase (TryR), a key enzyme that helps Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasites maintain a reducing intracellular environment by reducing trypanothione disulphide [80]. Another possible explanation for the observed antiprotozoal activity of the crude fungus extract is the presence of chaulmoogric acid. Based on the observation that chaulmoogric acid was incorporated into the phospholipid and triacylglycerol fractions of the cells of microorganisms, Cabot and Goucher [81] suggested that the anti-microbial properties could result from a “perturbation of membrane process.” Generally speaking, antileishmanial activity acids and esters are more active than corresponding alcohols, which show only marginal activity [72].

Conclusion

Endophytic fungi live within and participate in a complex web of interactions between themselves, the plant host, other endophytes, and phytopathogens. As a result, they produce bioactive compounds that can be useful in combating neglected tropical diseases. The characterization of endophytes present in ornamental plants is still incipient. This is the first report investigating both the diversity of cultivable endophytic fungi present in T. granulosa and the identity of compounds produced by the endophytic fungus P. capitalensis. Although the crude extract of P. capitalensis demonstrates antileishmanial and antitrypanosomal activities, the isolation of the compounds from the extract in this study, together with a study elucidating the mechanistic details for metabolite action in the cellular biochemistry of protozoa, constitute an initial step in understanding of the relationship between metabolites and pathogens.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1177 kb)

Funding information

The authors are grateful to CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) for scholarships (Finance code 001) and to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) (307603/2017-2) and the SETI/UGF (TC n.65/2018) for financial support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brasil/Ministério Do Meio Ambiente (2011) Espécies nativas da flora brasileira de valor econômico atual ou potencial: Plantas para o futuro - Região Sul. http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/sbf2008_dcbio/_ebooks/regiao_sul/Regiao_Sul.

- 2.Kuster RM, Arnold N, Wessjohann L. Anti-fungal flavonoids from Tibouchina grandifolia. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2009;37:63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2009.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobrinho AP, Minho AS, Ferreira LCL, Martins GR, Boylan F, Fernandes PD. Characterization of anti-inflammatory effect and possible mechanism of action of Tibouchina granulosa. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;69:706–713. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piza ACMT, Hokka CO, Sousa CP. Endophytic Actinomycetes from Miconia albicans (Sw.) Triana (Melastomataceae) and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity. J Sci Res Rep. 2015;4:281–291. doi: 10.9734/JSRR/2015/13237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza AQL, Souza ADL, Astolfi-Filho S, Belém Pinheiro ML, Sarquis MIM, Pereira JO. Antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi isolated from amazonian toxic plants: Palicourea longiflora (aubl.) rich and Strychnos cogens bentham. Acta Amaz. 2004;34:185–195. doi: 10.1590/S0044-59672004000200006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pires IMO, Silva AV, Santos MGS, Bezerra JDP, Barbosa RN, Silva DCV, Svedese VM, Souza-Motta CM, Paiva LM. Antibacterial potential of endophytic fungi from cacti of the Caatinga, a tropical dry forest in northeastern Brazil. Gaia Scientia. 2015;9:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heath RN, Roux J, Slippers B, Drenth A, Pennycook SR, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Occurrence and pathogenicity of Neofusicoccum parvum and N. mangiferae on ornamental Tibouchina species. For Pathol. 2011;41:48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira BA, Castro-Silva MA. Endospore-forming rhizobacteria associated with Tibouchina urvilleana in areas affected by coal-mining waste. R Bras Ci Solo. 2010;34:563–567. doi: 10.1590/S0100-06832010000200030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzoni-Viveiros SC, Trufem SFB. Effects of air and soil pollution on the root system of the Tibouchina pulchra Cogn. (Melastomataceae): arbuscular mycorrhizal associations and morphology in Atlantic Forest area. Braz J Bot. 2004;27:337–348. doi: 10.1590/S0100-84042004000200013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matias SR, Pagano MC, Muzzi FC, Oliveira CA, Carneiro AA, Horta SN, Scotti MR. Effect of rhizobia, mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in the rhizosphere of native plants used to recover an iron ore area in Brazil. Eur J Soil Biol. 2009;45:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2009.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urcelay C, Tecco PA, Chiarini F. Micorrizas arbusculares del tipo ‘Arum’ y ‘Paris’ y endófitos radicales septados oscuros en Miconia ioneura y Tibouchina paratropica (Melastomataceae) Bol Soc Argent Bot. 2005;40(3–4):151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sales MA, Gonçalves JF, Dahora JS, Medeiros AO. Influence of leaf quality in microbial decomposition in a headwater stream in the Brazilian Cerrado: a 1-year study. Microb Ecol. 2015;69:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Der AAHA, Vanev S. A revision of the species described in Phyllosticta. Utrecht, Netherlands: CBS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glienke C, Pereira O, Stringari D, Fabris J, Kava-Cordeiro V, Galli-Terasawa L, Cunnington J, Shivas R, Groenewald J, Crous PW. Endophytic and pathogenic Phyllosticta species, with reference to those associated with citrus black spot. Persoonia. 2011;26:47–56. doi: 10.3767/003158511X569169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues KF, Sieber TN, Gru¨nig CR, Holdenrieder O. Characterization of Guignardia mangiferae isolated from tropical plants based on morphology, ISSR-PCR amplifications and ITS1-5.8S-ITS2. Mycol Res. 2004;108:45–52. doi: 10.1017/S0953756203008840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan X, Sikora RA, Zheng J. Potential use of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) endophytic fungi as seed treatment agents against root−knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:219–225. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strobel G. Rainforest endophytes and bioactive products. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2002;22:315–333. doi: 10.1080/07388550290789531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evidente A, Cimmino A, Andolfi A, Vurro M, Zonno M, Motta A. Phyllostoxin and phyllostin, bioactive metabolites produced by Phyllosticta cirsii, a potential mycoherbicide for Cirsium arvense biocontrol. J Agri Food Chem. 2008;56:884–888. doi: 10.1021/jf0731301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijeratne EMK, Paranagama PA, Marron MT, Gunatilaka MK, Arnold AE, Gunatilaka AAL. Sesquiterpene quinones and related metabolites from Phyllosticta spinarum, a fungal strain endophytic in Platycladus orientalis, of the sonoran desert. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:218–222. doi: 10.1021/np070600c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumaran RS, Muthumary J, Hur BK (2008) Taxol from Phyllosticta citricarpa, a leaf spot fungus of the angiosperm Citrus medica. J Biosci Bioeng 106, 106:103. 10.1263/jbb.106.103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Balde ES, Andolfi A, Bruye’re C, Cimmino A, Lamoral-Theys D, Vurro M, Van Damme M, Altomare C, Mathieu V, Kiss R, Evidente A. Investigations of fungal secondary metabolites with potential anticancer activity. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:969–971. doi: 10.1021/np900731p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calve BL, Lallemand B, Perrone C, Lenglet G, Depauw C, Goietsenoven GV, Bury M, Vurro M, Herphelin F, Andolfi A, Zonno MC, Mathieu V, Dufrasne F, Antwerpen PV, Poumay Y, David-Cordonnier MH, Evidente A, Kiss R. In vitro anticancer activity, toxicity and structure–activity relationships of phyllostictine a, a natural oxazatricycloalkenone produced by the fungus Phyllosticta cirsii. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;254:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comstock JC, Martinson CA, Gengenbach BG. Host specificity of a toxin from Phyllosticta maydis for Texas cytoplasmically male-sterile maize. Phytopathology. 1973;63:1357–1361. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-63-1357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wikee S, Lombard L, Nakashima C, Motohashi K, Chukeatirote E, Cheewangkoon R, McKenzie EHC, Hyderous KD, Crous PW. A phylogenetic re-evaluation of Phyllosticta (Botryosphaeriales) Stud Mycol. 2013;76:1–29. doi: 10.3114/sim0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO (2017a) Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). http://www.who.int/chagas/en/ (accessed 08.11.2018)

- 26.Hata K, Futai K. Endophytic fungi associated with healthy pine needles and needles infested by the pine needle gall midge, Thecodiplosis japonensis. Can J Bot. 1995;73:384–390. doi: 10.1139/b95-040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castellani A. Maintenance and cultivation of common pathogenic fungal in sterile distilled water for the researches. J Trop Med Hyg. 1967;70:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raeder U, Broda P. Rapid preparation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1985;1:17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1985.tb01479.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pamphile JA, Rocha CLMSC, Azevedo JL. Co-transformation of a tropical maize endophytic isolate of Fusarium verticillioides (synonym F. moniliforme) with gusA and nia genes. Genet Mol Biol. 2004;27:253–258. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572004000200021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carbone I, Kohn L. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia. 1999;91:553–556. doi: 10.2307/3761358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego pp: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katoh K, Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:286–298. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidya G, Lohman DJ, Meier R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 2011;27:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre: Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rambaut A (2009) FigTree v1. 3.1: tree figure drawing tool. Website: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree. Accessed 15 July 2015

- 37.Taylor JE, Hyde KD, Jones EBG. Endophytic fungi associated with the temperate palm, Trachycarpus fortunei, within and outside its natural geographic range. New Phytol. 1999;142:335–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00391.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva RL d O, Luz JS, Silveira EB, Cavalcante UMT. Endophytic fungi of Annona spp.: isolation, enzymatic characterization of isolates and plant growth promotion in Annona squamosa L. seedlings. Acta Bot Bras. 2006;20:649–655. doi: 10.1590/S0102-33062006000300015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peixoto Neto PAS, Azevedo JL, Caetano LC. Microrganismos endofíticos em plantas: status atual e perspectivas. B Latinoam Caribe Pl. 2004;3:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyde KD, Soytong K. The fungal endophyte dilemma. Fungal Divers. 2008;33:163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhoden SA, Garcia A, Rubin-Filho CJ, Azevedo JL, Pamphile JA. Phylogenetic diversity of endophytic leaf fungus isolates from the medicinal tree Trichilia elegans (Meliaceae) Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:2513–2522. doi: 10.4238/2012.June.15.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva-Hughes AF, Wedge DE, Cantreel Carvalho CR, Pan Z, Moraes MRR, Madoxx CL, Rosa LH. Diversity and antifungal activity of the endophytic fungi associated with the native medicinal cactus Opuntia humifusa (Cactaceae) from the United States. Microbiol Res. 2015;175:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomes RR, Glienke C, Videira SIR, Lombard L, Groenewald J, Crous PW. Diaporthe: a genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Persoonia. 2013;31:1–4. doi: 10.3767/003158513X666844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murali TS, Suryanarayanan TS, Geeta R. Endophytic Phomopsis species: host range and implications for diversity estimates. Can J Microbiol. 2006;52:673–680. doi: 10.1139/w06-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bottela L, Diez JJ. Phylogenic diversity of fungal endophytes in Spanish stands of Pinus halepensis. Fungal Divers. 2011;47:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suryanarayanan TS, Murali TS, Venkatesan G. Occurrence and distribution of fungal endophytes in tropical forests across a rainfall gradient. Can J Bot. 2002;80:818–826. doi: 10.1139/b02-069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dean R, Van Kan JAL, Pretorius ZA, Hammond-Kosack KE, Di Pietro A, Spanu PD, Rudd JJ, Dickman M, Kahmann R, Ellis J, Foster GD. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farr DF, Rossman AY (2013) Fungal databases, Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA http://ntars-gringov/fungaldatabases/ Acessed 30 November 2017

- 49.Auyong FR, Taylor PWJ. Genetic transformation of Colletotrichum truncatum associated with anthracnose disease of chili by random insertional mutagenesis. J Basic Microbiol. 2012;52:372–382. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barimani M, Pethybridge SJ, Vaghefi N, Hay FS, Taylor PWJ. A new anthracnose disease of pyrethrum caused by Colletotrichum tanaceti sp. nov. Plant Pathol. 2013;62:1248–1257. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chomnunti P, Schoch CL, Aguirre-Hudson B, Ko-Ko TW, Hongsanan S, Jones EBG, Kodsueb R, Phookamsak R, Chukeatirote E, Bahkali AH, Hyde KD. Capnodiaceae. Fungal Divers. 2011;51:103–134. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bissett J. Discochora yuccae sp. nov. with Phyllosticta and Leptodothiorella synanamorphs. Can J Bot. 1986;64:1720–1726. doi: 10.1139/b86-230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van der Aa HA. Studies in Phyllosticta I. Stud Mycol. 1973;5:1–110. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okane I, Lumyong S, Nakagiri A, Ito T. Extensive host range of an endophytic fungus, Guignardia endophyllicola (anamorph: Phyllosticta capitalensis) Mycoscience. 2003;44:353–336. doi: 10.1007/s10267-003-0128-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wulandari NF, Bhat DJ, To-anun C Redisposition of species from the Guinardia sexual state of Phyllosticta. Plant Pathol Quar. 2014;4:45–85. doi: 10.5943/ppq/4/1/6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santos MS, Orlandelli RC, Polonio JC, Ribeiro MA d S, Sarragioto MH, Azevedo JL, Pamphile JA. Endophytes isolated from passion fruit plants: molecular identification, chemical characterization and antibacterial activity of secondary metabolites. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2017;7:38–43. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2017.70405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Entwistle ID, Howard CC, Johnstone RA. Isolation of brefeldin a from Phyllosticta medicaginis. Phytochem. 1974;13:173–174. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)91288-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calhoun LA, Findlay JA, Miller J, Whitney NJ. Metabolites toxic to spruce budworm from balsam fir needle endophytes. Mycol Res. 1992;96:281–286. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80939-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun Z-H, Liang F-L, Wu W, Chen Y-C, Pan Q-L, Li H-H, Ye W, Liu H-X, Li S-N, Tan G-H, Zhang W-M. Guignardones P–S, new meroterpenoids from the endophytic fungus Guignardia mangiferae A348 derived from the medicinal plant Smilax glabra. Molecules. 2015;20:22900–22907. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Madala NE, Piater LA, Steenkamp PA, Dubery IA. Multivariate statistical models of metabolomic data reveals different metabolite distribution patterns in isonitrosoacetophenone-elicited Nicotiana tabacum and Sorghum bicolor cells. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:254. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eriksson L, Johansson E, Kettaneh-Wold N, Wikström C, Wold S. Design of experiments: principles and applications-Umetrics. Sweden: Umeå; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vakkuri O, Tervo J, Luttinen R, Ruotsalainen H, Rahkamaa E, Leppaluoto J. A cyclic isomer of 2-hydroxymelatonin: a novel metabolite of melatonin. Endocrinology. 1987;120:2453–2459. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-6-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takagi H, Ishiga Y, Watanabe S, Konishi T, Egusa M, Akiyoshi N, Matsuura T, Mori IC, Hirayama T, Kaminaka H, Shimada H, Sakamoto A. Allantoin, a stress-related purine metabolite, can activate jasmonate signaling in a MYC2-regulated and abscisic acid-dependent manner. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:2519–2532. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jia M-Q, Xiong Y-J, Xue Y, Wang Y, Yan C. Using UPLC-MS/MS for characterization of active components in extracts of Yupingfeng and application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study in rat plasma after oral administration. Molecules. 2017;22:810–827. doi: 10.3390/molecules22050810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tawfike AF, Abbott G, Young L, Edrada-Ebel R. Metabolomic-guided isolation of bioactive natural products from Curvularia sp., an endophytic fungus of Terminalia laxiflora. Planta Med. 2018;84(3):182–190. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tudela R, Ribas-Agustí A, Buxaderas S, Riu-Aumatell M, Castellari M, López-Tamames E. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) quantification of nine target indoles in sparkling wines. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:4772–4776. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ponti J, Colognato R, Franchini F, Gioria S, Simonelli F, Abbas K, Rossi F (2008) Uptake and cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles in MDCK and HepG2 cell lines. Available: ttp://www.aistriss.jp/projects/nedonanorisk/nanorisk_symposium2008/pdf/03 _122_en_ROSSI.pdf

- 68.Almeida TT, Ribeiro MAS, Polonio JC, Garcia FP, Nakamura CV, Meurer EC, Sarragiotto MH, Baldoqui DC, Azevedo JL, Pamphile JA (2017) Curvulin and spirostaphylotrichins r and u from extracts produced by two endophytic Bipolaris sp. associated to aquatic macrophytes with antileishmanial activity. Nat Prod Res:1–8. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1380011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Carvalho CR, Gonçalves VN, Pereira CB, Johann S, Galliza IV, Alves TMA, Rabelo A, Sobral EG, Zani LC, Rosa CA, Rosa LH. The diversity, antimicrobial and anticancer activity of endophytic fungi associated with the medicinal plant Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville (Fabaceae) from the Brazilian savannah. Symbiosis. 2012;57:95–107. doi: 10.1007/s13199-012-0182-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Higginbotham SJ, Arnold AE, Ibañez A, Spadafora C, Coley PD, Kursar TA (2013) Bioactivity of fungal endophytes as a function of endophyte taxonomy and the taxonomy and distribution of their host plants. PloS One 8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Smith PMC, Atkins CA. Purine biosynthesis. Big in cell division, even bigger in nitrogen assimilation. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:793–802. doi: 10.1104/pp.010912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tewari N, Ramesh N, Mishra RC, Tripathi RP, Srivastava VML, Gupta S. Leishmanicidal activity of phenylene bridged C2 symmetric glycosyl ureides. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4055–4059. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boudet AM. Evolution and current status of research in phenolic compounds. Phytochem. 2007;68(22–24):2722–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brenzan MA, Nakamura CV, Prado Dias Filho B, Ueda-Nakamura T. Antileishmanial activity of crude extract and coumarin from Calophyllum brasiliense leaves against Leishmania amazonensis. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanakaraju A, Rao YS, Prasad C. Review on selected antitubercular drug targeted proteins for strucuture based drug discovery and development. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;5:231–236. doi: 10.20959/wjpps201610-7667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stout KL, Hallock KJ, Kampf JW, Ramamoorthy A. N-acetyl-l-phenylalanine. Acta Crystallogr C. 2000;56:E100. doi: 10.1107/S0108270100001712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Horrobin DF. The role of essential fatty acids and prostaglandins in the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:465–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gubbala LP, Arutla S, Venkateshwarlu V (2016) Preparation and characterization of metaxalone nanoparticles prepared by high pressure homogenization. Am J Pharmtech Res 6

- 79.Guimarães DO, Borges WS, Kawano CY, Ribeiro PH, Goldman GH, Nomizo A, Thiemann OH, Oliva G, Lopes NP, Pupo MT. Biological activities from extracts of endophytic fungi isolated from Viguiera arenaria and Tithonia diversifolia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamilton CJ, Saravanamuthu A, Eggleston IM, Fairlamb AH. Ellman’s-reagent-mediated regeneration of trypanothione in situ: substrate economical microplate and time-dependent inhibition assays for trypanothione reductase. Biochem J. 2003;369:529–537. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cabot MC, Goucher CR. Chaulmoogric acid-assimilation into the complex lipids of mycobacteria. Lipids. 1981;16:146–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02535690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1177 kb)