Abstract

The human polyomaviruses (HPyVs) 10 and 11 have been detected in faecal material and are tentatively associated with diarrhoeal disease. However, to date, there are insufficient data to confirm or rule out this association, or even to provide basic information about these viruses, such as how they are distributed in the population, the persistence sites and their pathogenesis. In this study, we analysed stool specimens from Brazilian children with and without acute diarrhoea to investigate the excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 as well as their possible associations with diarrhoea. A total of 460 stool specimens were obtained from children with acute diarrhoea of unknown aetiology, and 106 stool specimens were obtained from healthy asymptomatic children under 10 years old. Samples were collected during the periods of 1999–2006, 2010–2012 and 2016–2017, and found previously to be negative for other enteric viruses and bacteria. The specimens were screened for HPyV10 and HPyV11 DNA by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Randomly selected positive samples were sequenced to confirm the presence of HPyV10 and HPyV11. The sequenced strains showed a percent of nucleotide identity of 93.4–99.6% and 85.5–98.9% with the reference HPyV10 and HPyV11 strains, respectively, confirming the PCR results. HPyV10 and HPyV11 were detected in 7.2% and 4.7% of the stool specimens from children with and without diarrhoea, respectively. The prevalence of both viruses was the same among children with diarrhoea and healthy children. There was also no difference between boys and girls or the degree of disease (severe, moderate or mild) among groups. Phylogenetic analysis showed that all of the genotypes described so far for HPyV10 and HPyV11 circulate in Rio de Janeiro. Our results do not support an association between HPyV10 and HPyV11 in stool samples and paediatric gastroenteritis. Nevertheless, the excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 in faeces indicates that faecal-oral transmission is possible.

Keywords: Polyomavirus, HPyV10, Malawi polyomavirus, HPyV11, Saint Louis polyomavirus

Introduction

Diarrhoeal disease is a major cause of death worldwide in children under the age of 5 years old, and its aetiology varies depending on the location, time of year and population studied [1]. Improvements in laboratory methodologies for the detection and identification of pathogens have intensified the search for new infectious agents that may be associated with diarrhoea [2]. The human polyomaviruses (HPyVs) Malawi (MWPyV or HPyV10) and St. Louis (StLPyV or HPyV11) have been detected in faecal material and are tentatively associated with diarrhoeal disease [3–5].

HPyVs are in the Polyomaviridae family and are non-enveloped, double-stranded circular DNA viruses [6]. There are 14 HPyV species [6, 7], but only four of them (HPyV1, HPyV2, HPyV5 and HPyV8) are currently associated with disease in humans [6]. HPyV10 has been found in the faeces of healthy and diarrhoeic individuals [3, 4, 8–10] as well as in the anal warts of an immunosuppressed patient with warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, immunodeficiency and myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome [11]. HPyV10 also has been detected in the tonsils and adenoids of healthy children [12], children with chronic tonsillar disease [13], nasopharyngeal aspirates of children with and without symptoms of respiratory disease [8, 9, 14] and samples of fluvial waters [15]. Therefore, the route of transmission and the pathogenic role of this virus are still not clear. HPyV11 has been detected in the faeces of children with and without diarrhoea [5, 10], the tonsils of children with chronic tonsillar disease [13], nose and throat swabs from kidney transplant patients [16], the skin of a patient with WHIM syndrome [17] and the urine from a renal transplant patient [5]. The transmission pathway and the pathogenic role of this virus also are unclear. In this study, we analysed stool specimens from Brazilian children with and without acute diarrhoea to investigate the excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 and their possible association with diarrhoea.

Material and methods

Faecal samples

A total of 460 stool specimens from children with acute diarrhoea of unknown aetiology and 106 stool specimens from healthy children under 10 years old, belonging to the collection of the Laboratory of Respiratory, Enteric and Ocular Viruses (LAVIREO) of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, were screened for HPyV10 and HPyV11 DNA by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The stool specimens were collected in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, during the following periods: 1999–2006, 2010–2012 and 2016–2017 and stored at − 80 °C. No specific scale was used to determine the severity of diarrhoea. However, the degree of disease severity was estimated from the type of medical care provided: severe diarrhoea (hospitalised), moderate diarrhoea (emergency care) and mild diarrhoea (outpatient care).

The diarrhoeal samples included 144 (31.3%) specimens collected from hospitalised patients and 316 (68.7%) specimens from outpatients. Of the outpatient samples, 109 (23.7%) were from the emergency department and 207 (45%) were from walk-in clinics. Only one specimen was obtained per patient. Regarding age, 284 (61.7%) specimens were from patients ≤ 2 years old, 137 (29.8%) specimens were from patients 2.1–5 years old and 39 (8.5%) specimens were from patients 5.1–10 years old. Of the 106 non-diarrhoeal specimens, obtained from individuals without diarrhoea, 20 (18.9%) were from patients ≤ 2 years old, 46 (43.4%) specimens were from patients 2.1–5 years old and 40 (37.7%) specimens were from patients 5.1–10 years old. Relevant clinical data were collected (including hospitalisation status, age, sex and clinical symptoms) during sample submission.

The specimens included in this study were found previously to be negative for other enteric viruses and bacteria, including rotavirus, norovirus, astrovirus, adenovirus, salivirus, Aichivirus A, Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter spp. and Shigella spp.

Viral detection

Stool suspensions were prepared in 10% (w/v) phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) and were centrifuged at 2500g for 5 min. Nucleic acids were extracted from 200 μL of each supernatant using the phenol-chloroform/proteinase K method [18], and PCR was performed with primers targeting the VP1 gene of each virus. In the first round of PCR, the primer sets MWS-AP3 (5′-CCTGATTGGATGCTACAAT-3′, forward, nt 1274–1292) [15] and AS-AP2mod (5′-TGCCTCCCACATATAYAAATT-3′, reverse, nt 1758–1778) as well as StLF-1270 (5′-CCTCACAGACATGTCCAATGG-3′, sense, nt 1270–1290) and StLR-1710 (5′-GTGGDGTGCCAGGAGTAT-3′, reverse, nt 1693–1710) were used to generate 505-bp and 441-bp fragments of HPyV10 and HPyV11, respectively. In the semi-nested PCR, the primer sets MWS-AP3 and MWR2-1728 (5′-GCAGTTTAATTTTAGCTGTACT-3′, reverse, nt 1728–1707) as well as StLF-1270 and StLR2-1652 (5′-TAAAGAAACAGCTTCCCATAA-3′, reverse, nt 1632–1652) were used to generate 455-bp and 383-bp fragments of HPyV10 and HPyV11, respectively. Primer position was estimated from the strain sequences HPyV10 (accession number NC_020106) and HPyV11 (accession number JQ898292) available from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). DNA samples were subjected to 1 cycle at 94 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 50 °C or 55 °C for 40 s (for HPyV10 or HPyV11, respectively), and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Five microliters of the first round PCR products was subjected to a semi-nested PCR under the same conditions. The PCR products were separated by 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide and visualised under UV light. A 100-bp DNA ladder (Ludwig Biotec, RS, Brazil) was used to determine molecular size.

The PCR results were confirmed by sequencing the DNA amplified from nine strains of HPyV10, detected between 2001 and 2016, and 11 strains of HPyV11, detected between 2004 and 2006, which had a high viral load as determined by observation of the amplicon on the agarose gel after dilution of 10−7. The DNA samples were sent for sequencing to Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea) using the company protocol and the semi-nested PCR primers that amplify a portion of the VP1 gene. Overlapping sequences were assembled and edited using SeqMan, EditSeq and MegAlign in the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Statistical significance was estimated by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates. Sequences were compared with HPyV10 and 11 strain sequences available in the GenBank. The sequences generated in this study were deposited into GenBank under accession numbers MG641726-MG641746.

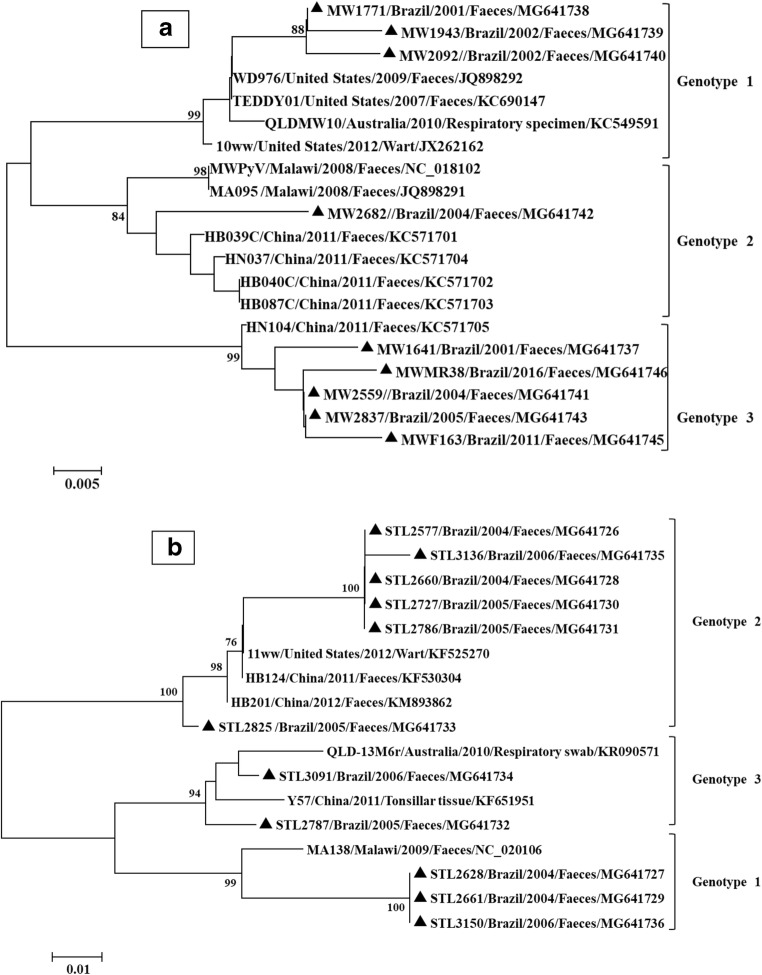

Phylogenetic analysis was carried out with MEGA software, version 7.0.26. Evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method. Dendrograms were constructed by the neighbour-joining method [19]. To identify the genotypes, reference strains were used for each genotype, according to the classification previously proposed for HPyV10 and HPyV11 [13]. The name, source of isolation, country of detection and accession numbers of the reference strains used are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram constructed from the partial nucleotide sequences of the VP1 gene from HPyV10 (a) and HPyV11 (b) strains. Distances were corrected with the maximum composite likelihood method. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbour-joining method. Statistical support was provided by bootstrapping 1000 pseudoreplicates. Bootstrap values above 75% are given at branch nodes. The distance scale is in substitutions/site. Reference samples are identified by GenBank accession numbers. The country, year of detection and source of isolation of the strains are presented in the figure. Black triangles indicate the strains sequenced in this study

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of means and rates between the various groups was tested using the χ2 test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 460 diarrhoeal samples analysed, 33 (7.2%) were HPyV positive. Of these, 11 (2.4%) samples were positive for HPyV10, 20 (4.4%) samples were positive for HPyV11 and 2 (0.4%) samples were positive for both viruses. Among the 106 non-diarrhoeal samples, 5 (4.7%) samples were HPyV positive. Of these, 4 (3.8%) samples were positive for HPyV10 and 1 (0.9%) sample was positive for HPyV11 (Table 1). HPyV10 and HPyV11 were equally prevalent among children with diarrhoea and healthy children (2.4% versus 3.8%, p = 0.51 and 4.4% versus 0.9%, p = 0.082, respectively). Positive samples were detected throughout the study period except for the years 2010 and 2017.

Table 1.

Age distribution of HPyV-positive samples

| Age (years) | Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoeal | Non-diarrhoeal | |||

| No. of samples tested | No. of positive samples | No. of samples tested | No. of positive samples | |

| 0–2 | 284 | 26 | 20 | 0 |

| 2.1–5 | 137 | 6 | 46 | 2 |

| 5.1–10 | 39 | 1 | 40 | 3 |

| Total | 460 | 33 (7.2%) | 106 | 5 (4.7%) |

Diarrhoeal samples were obtained from children with severe diarrhoea (hospitalised), moderate diarrhoea (emergency care) and mild diarrhoea (outpatient care). The presence of HPyV10 and/or HPyV11 DNA was detected in patients of all grades of disease, and there was no significant difference between the various categories (p = 0.426).

Most of the positive diarrhoeal samples (78.8%, n = 26) were from children ≤ 2 years old, and 18.2% (n = 6) were from children between 2.1 and 5 years old. Only one positive sample was detected among the older children, and it was from a 6-year-old girl (Table 2). Our data did not show a significant difference in relation to the age group and the positivity for HPyV10 or HPyV11 (p = 0.137). Ten (30.3%) positive samples were obtained from hospitalised children, whereas 23 (69.7%) positive samples were from outpatients. Of the positive samples from outpatients, 9 (27.3%) were from the emergency department and 14 (42.4%) were from walk-in clinics (Table 2). Among the positive non-diarrhoeal samples, 2 were from children aged 2.1–5 years old and 3 were from older children (Table 2). The number of positive samples in this age group was insufficient to calculate the statistical significance.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the HPyV-positive samples detected in this study

| Year | Virus detected | No. of samples | Age1 | Status2 | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | HPyV11 | 1 | 2.1–5 y | H | Diarrhoea |

| 2000 | HPyV11 | 3 | < 2 y | H (23), C (1) | Diarrhoea |

| 2001 | HPyV10 | 1 | < 2 y | C | Diarrhoea |

| Co-infection | 1 | < 2 y | E | Diarrhoea | |

| 2002 | HPyV10 | 2 | < 2 y | E, C | Diarrhoea |

| 2003 | HPyV11 | 1 | < 2 y | E | Diarrhoea |

| 2004 | HPyV10 | 2 | < 2 y | H; C | Diarrhoea |

| HPyV11 | 6 | < 2 y | H (2), E (2), C (2) | Diarrhoea | |

| 2005 | HPyV10 | 5 | < 2 y (4), 5.1–10 y (1) | H (1), E (2), C (2) | Diarrhoea |

| HPyV11 | 3 | < 2 y (1), 2.1–5 y (2) | H (1), E (1), C (1) | Diarrhoea | |

| Co-infection | 1 | < 2 y | C | Diarrhoea | |

| 2006 | HPyV11 | 5 | < 2 y (4), 2.1–5 y (1) | H (2), E (1), C (1) | Diarrhoea |

| 2010 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2011 | HPyV10 | 2 | 2.1–5 y | C | Diarrhoea |

| 5.1–10 y | No diarrhoea | ||||

| 2012 | HPyV11 | 1 | 2.1–5 y | C | Diarrhoea |

| 2016 | HPyV10 | 3 | 2.1–5 y (1), 5.1–10 y (2) | No diarrhoea | |

| HPyV11 | 1 | 2.1–5 y | No diarrhoea | ||

| 2017 | – | – | – | – | – |

1Years. 2H, hospitalised; E, emergency department; C, walk-in clinic. 3Number of positive samples

All nine HPyV10 and eleven selected HPyV11 strains were successfully sequenced (Fig. 1). The HPyV10 strains showed a percent of nucleotide identity of 93.4–99.6% with the reference HPyV10 strains (MWPyV, WD976, TEDDY01, QLDMW10, 10ww, MA095, HB039C, HN037, HB040C, HB087C, HN104) in the GenBank, while they had a percent of nucleotide identity with other HPyV species of 30.2–43.1%, confirming the PCR results. Phylogenetic analysis of the HPyV10 strains showed that three genotypes circulate in Rio de Janeiro (Fig. 1a). Samples belonging to genotype 1 were detected in 2001–2003 and presented nucleotide identities of 97.8–99% among themselves and 96.1–98.3% with the reference samples for this genotype. The sample belonging to genotype 2 was detected in 2004 and presented a nucleotide identity of 97.7–99% with the reference samples for this genotype. Samples belonging to genotype 3 were detected in 2001–2016 and had nucleotide identities of 98.1–100% among themselves and 98.5–99.3% with the reference samples for this genotype. The phylogenetic analysis results showed that the HPyV10 and HPyV11 strains were grouped into three clades, consistent with the existence of three genotypes.

The HPyV11 strains had a percent of nucleotide identity of 85.5–98.9% with the reference HPyV11 strains (11ww, HB124, HB201, QLD-13M6, Y57, MA138) in the GenBank while they had a percent of nucleotide identity with other HPyV species of 37–61.2%, confirming the PCR results. Phylogenetic analysis of the HPyV11 strains showed that three genotypes circulate in Rio de Janeiro (Fig. 1b). Samples belonging to genotype 1 were detected in 2005–2006 and had nucleotide identities of 98.1% among themselves and 97.3–98.1% with the reference samples for this genotype. The samples belonging to genotype 2 were detected in 2004 and 2006 and had nucleotide identities of 100% among themselves and 95.5–95.7% with the reference samples for this genotype. The samples belonging to genotype 3 were detected in 2004 and 2006 and had nucleotide identities of 95.3–100% among themselves and 96.4–98.9% with the reference samples for this genotype.

No significant difference was observed in the nucleotide identity percentage with respect to source of isolation (i.e. faeces, respiratory specimens or wart), country and year of detection for HPyV10 or HPyV11 strains.

Discussion

Because they were initially detected in faecal material, HPyV10 and HPyV11 were tentatively related to diarrhoeal disease [4, 20]. However, to date, there are insufficient data to confirm or rule out this association, or even to provide basic information about these viruses, such as how they are distributed in the population, the persistence sites and their pathogenesis. The detection of these viruses in different clinical specimens, such as faeces, respiratory secretions, tonsils and skin [3, 4, 9–11, 13, 16], suggests the occurrence of systemic infection, but it does not clarify transmission mechanisms, replication sites, persistence or pathogenesis.

Although no significant difference in positivity between the age groups was demonstrated, in this study, most of the HPyV-positive samples were from children ≤ 2 years old, in accordance with the generally accepted paradigm that primary HPyV infection usually occurs during childhood [6]. Siebrasse et al. analysed 514 faecal samples from children with diarrhoea admitted to St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA, of which 2.3% (12/514) of the children < 5 years old were positive for HPyV10 [3]. Similarly, Yu and co-workers detected HPyV10 in 3.4% of faecal samples (30/834) from children from the USA, Mexico and Chile, with and without diarrhoea [4]. HPyV10 was also detected in 7.2% of faecal samples (19/263) from children with and without diarrhoea in Australia [8] as well as 1.7% of children with diarrhoea in China [9]. In addition, these data have been confirmed by seroprevalence studies [21]. Regarding HPyV11, the literature data suggest the occurrence of primary infection during childhood, both through the detection of antibodies [14] and the detection of viral particles in clinical specimens [5, 10, 20]. Moreover, Lim and colleagues analysed 514 faecal samples from children with diarrhoea > 2 years old at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA, and detected the presence of the virus in 7 (1.4%) of the children [5]. Furthermore, a study in China evaluated the presence of HPyV11 in faecal samples from 779 children (508 with diarrhoea and 271 controls); the virus was detected in 11 (2.2%) children with diarrhoea, of which 4 had no co-infection with other enteric pathogens, and 8 (2.9%) children in the control group [20]. Finally, Melamed and colleagues analysed 196 faecal samples (98 with diarrhoea and 98 controls) from children admitted to Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA, and one child in the control group tested positive for HPyV11 [10].

The detection of the virus in clinical samples does not necessarily clarify the possibility of establishing persistent infection, as has been demonstrated for other HPyV species [6, 22, 23]. However, in a study by Siebrasse and colleagues (2012), three consecutive faecal samples were obtained from a 5-year-old lung transplant recipient over a period of 4 months, and all three samples tested positive for HPyV11; this finding suggests a persistent infection [3]. In a study by Yu and co-workers, two samples obtained 91 days apart from the same child were positive for HPyV10, raising the possibility of chronic infection [4]. Similarly, in a study by Rockett et al., three positive faecal specimens were obtained from the same patient over a period of 5 days, demonstrating prolonged excretion of the virus [8]. Therefore, the prospective studies are needed to confirm the duration of excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 in faeces as well as the possible establishment of persistent infection.

We detected co-infection by HPyV10 and HPyV11 in samples from two immunocompetent children with diarrhoea. The occurrence of co-infections had previously been described in the diarrhoeal stools of a 5-year-old child who had received a lung transplantation. Three faecal samples were obtained from this patient: the first and second samples were obtained on consecutive days, and the third sample was collected 4 months later. All samples were positive for both viruses [3, 5]. However, further studies are needed to confirm persistent excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 in faeces.

Phylogenetic studies have revealed the genetic diversity of the HPyV10 and HPyV11 strains, and three distinct genotypes have been described for each of these species [5, 9, 13, 20].

Previous studies have demonstrated the wide geographical circulation of these viruses. Strains of HPyV10 genotype 1 have been detected in the USA, Australia and China; strains of genotype 2 have been detected in Malawi and China; and strains of genotype 3 have been described in China [3, 8, 13]. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated the circulation of all three HPyV10 genotypes in Rio de Janeiro during the study period, including genotype 3 that had only previously been observed in China [13]. With respect to HPyV11, strains of genotype 1 have been detected in the USA, China and Australia; strains of genotype 2 have been detected in the USA, Malawi and Gambia; and strains of genotype 3 have been detected in the USA and China [5, 13, 16]. All three genotypes were detected in the present study. The covariance of the different HPyV10 and HPyV11 genotypes was observed throughout the study. However, the scarcity of data in the literature, particularly in Brazil, makes it difficult to analyse the genetic diversity of these viruses.

As epidemiological information on these viruses is scarce and limited to a small number of countries, and these studies are usually performed with samples stored for a few years and viral detection is performed by PCR, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the overall characteristics of these infections or the causes of any variations.

In conclusion, this study describes for the first time the circulation of HPyV10 and HPyV11 in Brazil. Although, our results did not support an association between HPyV10 and HPyV11 in stool samples and paediatric gastroenteritis as had been reported previously [20]. Nevertheless, the excretion of HPyV10 and HPyV11 in faeces indicates that faecal-oral transmission is possible. This assumption is reinforced by data from the literature demonstrating the presence of HPyV10 in river water, which would allow the transmission of this virus by ingestion of contaminated food and water [15]. Furthermore, identification of the circulating HPyVs can help to elucidate their biodiversity, improve our understanding of their potential health burden and enable a prompt response in case of outbreaks.

Acknowledgements

We thank Soluza dos Santos Gonçalves for technical assistance.

Funding information

This study was supported, in part, by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant numbers 404984/2018-5 and 301469/2018-0) and the Fundação Carlos Chagas de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (FAPERJ, grant number E-26/202.909/2017). M.S.P. was supported by a grant from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Compliance with ethical standards

The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital (protocol 005/11) of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The funders were not involved in the study design, data collection, data interpretation or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dennehy PH. Viral gastroenteritis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:63–64. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182059102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oude Munnink BB, van der Hoek L. Viruses causing gastroenteritis: the known, the new and those beyond. Viruses. 2016;8:42. doi: 10.3390/v8020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siebrasse EA, Reyes A, Lim ES, Zhao G, Mkakosya RS, Manary MJ, Gordonj I, Wang D. Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool. J Virol. 2012;86:10321–11036. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu G, Greninger AL, Isa P, Phan TG, Martinez MA, De La Luz SM, Contreras JF, Saintos-Preciato JI, Parsonnet J, Miller S, Derisi JL, Delwart E, Arias CF, Chiu CY. Discovery of a novel polyomavirus in acute diarrheal samples from children. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim ES, Reyes A, Antonio M, Saha D, Ikumapayi UN, Adeyemi M, Stine O, Skelton R, Brennan DC, Mkakosya RS, Manary MJ, Gordon JI, Wang D. Discovery of STL polyomavirus, a polyomavirus of ancestral recombinant origin that encodes a unique T antigen by alternative splicing. Virology. 2013;436:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moens U, Krumbholz A, Ehlers B, Zell R, Johne R, Calvignac-Spencer S, Lauber C. Biology, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses: an update. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;54:18–38. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gheit T, Dutta S, Olivera J, Robitaille A, Hampras S, Combesa JD, Chopina SM, Kelma FLC, Neil F, Cherpelisc B, Giulianoe AR, Franceschia S, McKaya J, Rollisonb DE, Tommasinoa M. Isolation and characterization of a novel putative human polyomavirus. Virology. 2017;506:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockett RJ, Sloots TP, Bowes S, O’Neill N, Ye S, Robson J, Whiley DM, Lambert SB, Wang D, Nissen MD, Bialasiewicz S. Detection of novel polyomaviruses, TSPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, HPyV9 and MWPyV in feces, urine, blood, respiratory swabs and cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma FL, Li DD, Wei TL, Li JS, Zheng LS. Quantitative detection of human Malawi polyomavirus in nasopharyngeal aspirates, sera, and feces in Beijing, China, using real-time TaqMan-based PCR. Virol J. 2017;14:152. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melamed R, Storch GA, Holtz LR, Klein EJ, Herrin B, Tarr PI, Denno DM. Case-control assessment of the roles of noroviruses, human bocaviruses 2, 3, and 4, and novel polyomaviruses and astroviruses in acute childhood diarrhea. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:e49–e54. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buck CB, Phan GQ, Raiji MT, Murphy PM, McDermott DH, McBride AA. Complete genome sequence of a tenth human polyomavirus. J Virol. 2012;86:10887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01690-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papa N, Zanotta N, Knowles A, Orzan E, Comar M. Detection of Malawi polyomavirus sequences in secondary lymphoid tissues from Italian healthy children: a transient site of infection. Virol J. 2016;13:97. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng J, Li K, Zhang C, Jin Q. MW polyomavirus and STL polyomavirus present in tonsillar tissues from children with chronic tonsillar disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:97.e1–97.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockett RJ, Bialasiewicz S, Mhango L, Gaydon J, Holding R, Whiley DM, Lambert SB, Ware RS, Nissen MD, Grimwood K, Sloots TP. Acquisition of human polyomaviruses in the first 18 months of life. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:365–367. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres C, Barrios ME, Cammarata RV, Cisterna DM, Estrada T, Novas SM, Cahn P, Fernandez MD, Mbayed VA. High diversity of human polyomaviruses in environmental and clinical samples in Argentina: detection of JC, BK, Merkel-cell, Malawi, and human 6 and 7 polyomaviruses. Sci Total Environ. 2016;542(Pt A):192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bialasiewicz S, Rockett RJ, Barraclough KA, Leary D, Dudley KJ, Isbel NM, Sloots TP. Detection of recently discovered human polyomaviruses in a longitudinal kidney transplant cohort. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2734–2740. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastrana DV, Fitzgerald PC, Phan GQ, Raiji MT, Murphy PM, McDermott DH, Velez D, Bliskovsky V, McBride AA, Buck CB (2013) A divergent variant of the eleventh human polyomavirus species, Saint Louis polyomavirus. Genome Announc 1:pii: e00812–13. 10.1128/genomeA.00812-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Scorsato AP, Telles JEQ. Factors that affect the quality of DNA extracted from biological samples stored in paraffin blocks. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2011;47:541–548. doi: 10.1590/S1676-24442011000500008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics19. analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li K, Zhang C, Zhao R, Xue Y, Yang J, Peng J, Jin Q. The prevalence of STL polyomavirus in stool samples from Chinese children. J Clin Virol. 2015;66:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicol JT, Leblond V, Arnold F, Guerra G, Mazzoni E, Tognon M, Coursaget P, Touzé A. Seroprevalence of human Malawi polyomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:321–323. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02730-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krumbholz A, Bininda-Emonds OR, Wutzler P, Zell R. Phylogenetics, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:784–799. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feltkamp MC, Kazem S, van der Meijden E, Lauber C, Gorbalenya AE. From Stockholm to Malawi: recent developments in studying human polyomaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:482–496. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.048462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]