Abstract

It is well known in clinical practice that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is closely associated with brain insulin resistance, and the cerebral insulin pathway has been proven to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD. However, finding the most efficient way to improve brain insulin resistance remains challenging. Peripheral administration of insulin does not have the desired therapeutic effect and may induce adverse reactions, such as hyperinsulinemia, but intranasal administration may be an efficient way. In the present study, we established a brain insulin resistance model through an intraventricular injection of streptozotocin, accompanied by cognitive impairment. Following intranasal insulin treatment, the learning and memory functions of mice were significantly restored, the neurogenesis in the hippocampus was improved, the level of insulin in the brain increased, and the activation of the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt-GSK3β insulin signal pathway, but not the Ras-Raf-MEK-MAPK pathway, was markedly increased. The olfactory bulb–subventricular zone–subgranular zone (OB-SVZ-SGZ) axis might be the mechanism through which intranasal insulin regulates cognition in brain-insulin-resistant mice. Thus, intranasal insulin administration may be a highly efficient way to improve cognitive function by increasing cerebral insulin levels and reversing insulin resistance.

Keywords: Intranasal insulin, STZ, IRS-1 pathway, Neurogenesis, Cognitive function

Introduction

The risk of cognitive function disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is increased in patients with diabetes. Insulin is an important neurohormone that plays a key role in brain energy metabolism, neurogenesis, axonal migration and cognitive function (Chen et al. 2014). Insulin resistance has been shown to be a pathogenic mechanism of impaired cognitive dysfunction (Sasaoka et al. 2014; Nakamura et al. 2017). Insulin plays a key role in learning and memory and directly regulates the pathway required for the type of learning and memory compromised in early AD (Dineley et al. 2014). The dysregulation of the cerebral insulin signaling pathway can promote a localized increase in amyloid β (Aβ) and the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, and Aβ oligomers can cause impaired insulin signaling at insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) via mechanisms involving TNF-α and JNK activation (Sasaoka et al. 2014; Morales-Corraliza et al. 2016). The attenuation of the PI-3 kinase (PI3K) pathway and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) β activation are also involved in the hyperphosphorylation of tau (Wu et al. 2013; Zang et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2013). Thus, AD has been described as type III diabetes (Dineley et al. 2014; Ahmed et al. 2015).

Insulin resistance in the brain is difficult to reverse through peripheral direct insulin supplementation (Gray et al. 2014), likely because peripheral insulin is a macromolecule that cannot pass through the blood–brain barrier (Banks 2012). In addition, previous studies have reported that elevating insulin concentration in the peripheral blood elevates the consumption of insulin-degrading enzyme in the brain, which is a key enzyme that degrades β-amyloid protein in the brain and has a negative effect on the degradation of Aβ (Qiu and Folstein 2006). Craft et al. (Craft et al. 1996) reported that raising plasma insulin via an intravenous infusion while keeping plasma glucose at the fasting baseline level produces striking memory enhancement for patients with AD. However, an opposing study (Luchsinger et al. 2004) indicated that hyperinsulinemia can induce a significant decline in memory-related cognitive scores and a higher risk of AD in people without diabetes. Peripheral hyperinsulinemia does not influence central insulin receptor signaling or tau phosphorylation (Becker et al. 2012). Therefore, peripheral insulin supplementation to increase the activation of the insulin signaling pathway in the brain does not produce ideal results, and elevating the insulin level in the brain is a challenge that needs to be overcome.

Certain clinical trials (Craft et al. 2012; Claxton et al. 2015) have attempted to treat AD patients with intranasal insulin and reported effects on cognitive function. Insulin supplementation from the nasal cavity can enter cerebral circulation through the cavernous sinus capillaries, thus reducing the blockage of insulin by the blood–brain barrier. Yang et al. (2013) reported that intranasal insulin ameliorates tau hyperphosphorylation via the insulin pathway in a rat model of type 2 diabetes and suggested the potential use of intranasal insulin for the treatment of AD. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether intranasal insulin can improve brain insulin resistance. Indeed, the primary mechanism that should be targeted for the treatment of cognitive function has not been established.

Streptozotocin (STZ) is a structural analogue of glucose and N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc). It can be used to induce a decline in insulin-dependent glucose cellular uptake by GLUT-2 (Lenzen 2008; Naik et al. 2017). GLUT-2 is widely distributed in pyramidal neurons located in the neocortex and hippocampus (CA3 and dentate gyrus), which is the main area of the brain regulating learning and memory function (Talbot and Wang 2014). Based on the close analogy between human patients with AD and rats subjected to intracerebroventricular (I.C.V.) STZ injections with respect to brain metabolic and behavioral disturbances, the current concept of I.C.V. STZ has been defined as the nontransgenic metabolic model of sporadic AD by Hoyer’s group (Salkovic-Petrisic et al. 2009; Duelli et al. 1994; Grunblatt et al. 2007). In further research, the I.C.V.-injection-of-STZ model was extended to an insulin-resistant brain state (IRBS) (Frisardi et al. 2010; Correia et al. 2011), which is a condition characterized by decreased tissue sensitivity to the action of insulin (Grieb 2016). By using the I.C.V. injection of STZ, the main aim of the present study was to determine whether intranasal insulin administration could improve the cognitive function induced by brain insulin resistance. In addition, the potential mechanism through which intranasal insulin improves cognitive function in the brain was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Animal treatment

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Guangxi (Guangxi, China), were kept at 25 ± 2 °C under a daily 12-h light/dark cycle. All animals had free access to food and water. The experiments were performed in accordance with the ‘Policies on the Use of Animals and Humans in Neuroscience Research’, as approved by the Society for Neuroscience in 1995, and executed under the supervision and assessment of the Animal Ethics Committee of Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities.

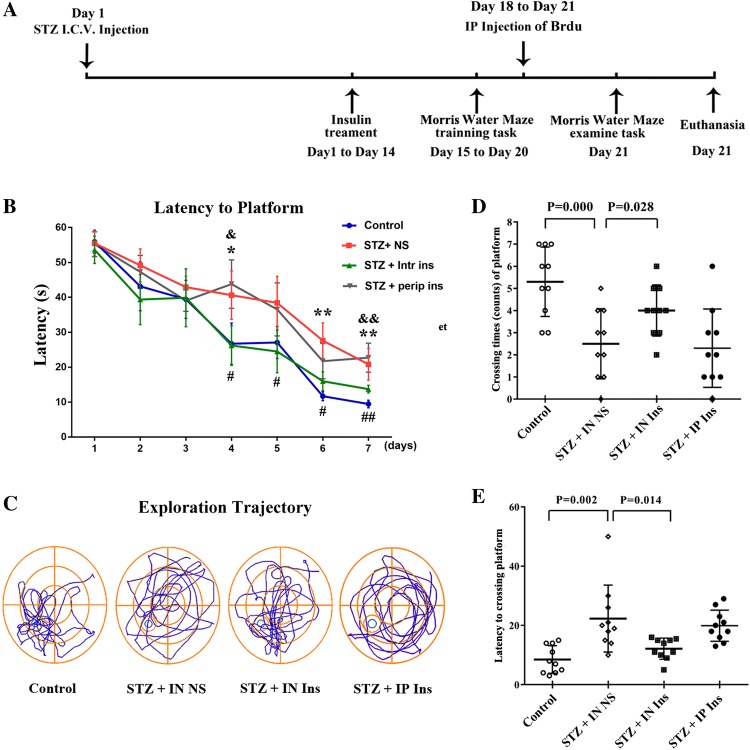

The duration of the experiments was 14 + 7 days. A diagram demonstrating the experimental process is shown in Fig. 1a. The animals were divided into four groups and received the following treatments (n = 10 per group): I.C.V. injection of saline (control group); I.C.V. injection of streptozotocin (STZ; 3 mg/kg, 5 μl) plus intranasal saline (20 μl per side) (STZ + IN NS); I.C.V. injection of STZ (3 mg/kg, 5 μl) plus intranasal insulin (20 μl per side) (STZ + IN ins); I.C.V. injection of STZ (3 mg/kg, 5 μl) plus intraperitoneal insulin (40 μl), STZ + IP ins. Each 20 μl insulin injection contained 1 IU insulin glargine.

Fig. 1.

Learning and memory function of mice in each group. a Mice were randomly allocated into three groups. The groups were treated with an I.C.V. injection of STZ or saline on the first day. They then underwent intranasal administration of insulin or saline in each group between days 1 and 14. Mice were trained in the Morris water maze during the next 6 days (days 15–20). In addition, the mice received BrdU injections on the last 3 days. On day 21, the mice underwent the Morris water maze testing task and were then euthanized. b Morris water maze training latency of mice in each group. The control group performed better than the STZ + IN NS group in the Morris water maze training experiment. Intranasal insulin administration reversed this effect, while intraperitoneal administration did not have a similar effect. c Swimming pathway for the three groups in the Morris water maze test. The STZ injection group performed worse than the control. Intranasal insulin treatment partly reversed the STZ effect, which was not observed in the intraperitoneal injection group. d, e Morris water maze test results in each group. The STZ + IN NS group performed poorly compared with the control group in first-crossing time and the frequency of crossing the platform, and intranasal insulin reversed this effect. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 STZ + IN NS versus control; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 STZ + IN ins versus STZ + IN NS; &P < 0.05 and &&P < 0.01 STZ + IP ins versus STZ + IN ins. STZ streptozotocin, BrdU 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine

On the first day, the I.C.V. STZ mice were administered a stereotaxic injection of STZ. Mice were first anesthetized using 2.5% avertin (2,2,2 tribromoethanol; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) (500 mg/kg) and then restrained onto a brain stereotaxic apparatus. The bregma coordinates for I.C.V. were 0.4 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.0 mm lateral to the midline and 2.0 mm from the dura. Following the injection, insulin or saline was intranasally or intraperitoneally injected into the mice twice daily between days 1 and 14. The intranasal administration was performed using a syringe, and the liquid was slowly poured into the nasal cavity with a 12-h interval. The mice were awake and placed in the supine position during the procedure. The PI3K activity inhibitor LY294002 was administered by an intraperitoneal injection between days 14 and 21. During the last 7 days (days 15–21) of the experiment, the animals received memory training by the Morris water maze (days 15–20) and underwent the testing task on the last day (day 21); they were then euthanized by 2.5% avertin, and the tissues were harvested after the animals stopped breathing. Relevant data were recorded using the Morris water maze system. The mice in each group were intraperitoneally injected with 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (50 mg/kg, twice per day) for 3 days (days 18–21; (Fig. 1a).

Morris water maze test

Cognitive functions were assessed by the Morris water maze test (Guo et al. 2018) (Beijing Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), which was performed for 8 days. The mice received training for seven consecutive days from 10:00 to 14:00, with three trials per day on the Morris water maze. During the first 7 days, the mice were trained to search for the platform for 60 s in the maze. If a mouse failed to locate the platform within the allotted time, the mouse was manually guided to the location of the platform. All animals were allowed to stay on the platform for 30 s per trial, whether or not the platform was identified; the mice then returned to their cages. On the last day, the animals underwent the testing task. In this task, the platform was removed from the maze, and only one trial was recorded. Mice were placed in the opposite quadrant (the one diagonal to the platform) and allowed to search for 60 s. All tasks were monitored using a tracking system. The mean target quadrant occupancy of all 4 test periods was calculated. Then, mice were euthanized, and tissues were collected immediately for further experiments.

Western blot analysis

Mice were euthanized following the Morris water maze test. The hippocampi were rapidly removed after euthanization and homogenized at 4 °C in lysis solution (50 mmol/l HEPES (pH 7.0), 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 1 mmol/l EGTA, 100 mmol/l NaF, 10 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/l Na3VO4, 10 μmol/l pepstatin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 mmol/l iodoacetic acid and 2 μg/ml leupeptin). The proteins extracted from the hippocampus were separated by 11 or 9% SDS–PAGE. For Aβ detection, samples were separated by 4–12% NuPAGE Bis–tris mini gels using NuPAGE LDS sample buffer, NuPAGE sample reducing agent and NuPAGE MES SDS running buffer (Invitrogen). The pages were electrotransferred onto an immobilon-P membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and then probed with primary antibodies (Table 1) at 4 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG and conjugated with horseradish peroxidase at a concentration of 1:5000 for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate kit (EMD Millipore).

Table 1.

Information of the primary antibodies used in this study

| Anitibodya | Specificitya | Type | Item numbers | Dilutionb | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | β-actin | Polyclonal | #3700 | 1:10,000 WB | Cell signaling |

| IRS-1 | Total IRS-1 | Polyclonal | ab52167 | 1:1000 WB/1:200 IHC | Abcam |

| p-IRS-1(Tyr612) | p-IRS-1 at Tyr612 | Polyclonal | 44-816G | 1:1000 WB | Thermo |

| Polyclonal | sc-17195-R | 1:50 IF/1:50 IHC | Santa Cruz | ||

| PI3K-p85α | Total PI3 Kinase p85 | Polyclonal | #4292 | 1:1000 WB | Cell signaling |

| p-PI3K-p85α (Tyr607) | p-PI3K-p85α at Tyr607 | Polyclonal | ab182651 | 1:1000WB | Abcam |

| Akt | Total Akt | Monoclonal | #4691 | 1:1000 WB | Cell signaling |

| p-Akt (Ser473) | p-Akt at Ser473 | Monoclonal | #4060 | 1:1000 WB | Cell signaling |

| GSK3β | Total GSK3β | Monoclonal | #9832 | 1:1000 WB/ | Cell signaling |

| p-GSK3β(Ser9) | p-GSK3β at Ser9 | Monoclonal | #5558 | 1:1000 WB/1:200 IHC/1:100 IF | Cell signaling |

| DCX | Doublecortin(C-18), Microtubule-associated protein in migrating and differentiating neurons | Polyclonal | sc-1084 | 1:1000 WB/1:50 IHC/1:50 IF | Santa Cruz |

| Neuro D | Neuro D(N-19), Helix–loop–helix protein expressed in differentiating neurons | Polyclonal | sc-8066 | 1:1000 WB/1:100 IHC | Santa Cruz |

| Brdu | 5-Bromodeoxyuridine | Monoclonal | ab6326 | 1:100 IF | Abcam |

| Aβ | Beta amyloid | Monoclonal | 6E10 | 1:1000 WB/1:200 IHC | Covance |

ap phosphorylated, bWB western blot, IHC immunohistochemistry, IF immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent staining

Mice were anesthetized using avertin and underwent heart perfusion with 0.9% ice-cold normal saline. The brains were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 48 h at 4 °C. After they were paraffin-embedded, the tissues were cut into 15-μm sections and rehydrated prior to antigen retrieval. The brain sections were incubated in 0.1% H2O2 in PBS for 20 min and treated with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min to increase cell membrane permeability. Subsequently, the sections were incubated in 5% BSA for 30 min to block nonspecific antigens and prepare them for primary antibody binding. For immunohistochemical staining, the tissues were incubated in primary antibodies (Table 1) for 12 h at 4 °C and incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. DAB was used for coloration, and dark brown staining was considered positive. The strength of positivity was semiquantified using ImageJ software to determine the staining intensity in each group.

For immunofluorescence staining, the pretreatment of tissue sections was performed as described for immunohistochemical staining. The sections were incubated with the primary antibody for 24 h at 4 °C, followed by the second antibody for an additional 24 h. After 1 h of incubation with the mixture of Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200) and Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat IgG, images of the sections were captured using a confocal laser microscope. The strength of positivity was semiquantified using ImageJ software to determine the staining intensity in each group.

For BrdU labeling, tissue sections were treated with 50% formamide and 2 × saline citrate at 65 °C for 1 h and 40 min. Then, sections were incubated in standard volumetric solution (pH = 8.5) for 15 min 3 times. Following blocking in 5% BSA, the sections were incubated with the BrdU primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200), and images were captured using a confocal laser microscope.

Every other brain section of one hemisphere was used for fluorescence and histochemical image analysis. Five hippocampal sections per animal were analyzed in a total of 4–6 animals per group. The total Aβ, NeuroD and BrdU load was determined by counting the positively stained plaques or labeled cells using the imaging software ImageJ. The DCX, p-IRS-1 and GSK3β were quantified by the staining intensity in the animal’s whole dentate gyrus. The quantification was performed in the dentate gyrus, and its area was measured with ImageJ software.

ELISA of insulin

Mice were anesthetized using avertin and received heart perfusion with ice-cold normal saline. The brain tissues were rapidly removed at various time points and homogenized at 4 °C in PBS. Peripheral blood was collected after stripping the eyeball. The insulin concentration in the tissue homogenate supernatant and peripheral blood was assayed using an ELISA kit (kt21071; MSKBIO). The quantification results of the insulin concentration in tissue samples are presented as the ratio to the β-actin level.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using SPSS 12.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance, followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test or Bonferroni analysis, was used to determine the statistical significance of the means. The level of significance for all analyses was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Intranasal insulin administration can improve STZ-induced learning and memory function deficits in mice

The learning and memory functions of mice were assessed using the Morris water maze in each group. In the training task during the first 7 days (days 14–21), the latency to find the platform decreased as the training time increased. However, the STZ + IN NS group exhibited a longer latency than the control after day 3 of the training task. The intranasal insulin administration could reverse this effect, but the intraperitoneal injection could not (Fig. 1b). Compared with the STZ group, the performance of the insulin-treated mice in finding the platform significantly improved after day 1. A similar phenomenon was observed during the testing task. Compared with the control group, the STZ + IN NS mice exhibited a more chaotic swimming trajectory, took a longer time to cross the platform the first time and exhibited a lower frequency of swimming past the platform (Fig. 1c–e). Following the intranasal administration of insulin, the performance of the mice in the test significantly improved. The learning and memory function of STZ mice was significantly ameliorated by the intranasal administration of insulin. No obvious enhancement was observed in the learning and memory function of STZ + IP mice when compared with the STZ group (Fig. 1c–e).

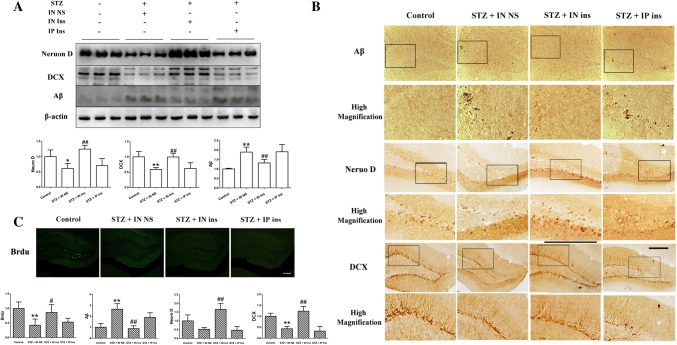

The decline in neurogenesis and Aβ deposition in STZ-treated mice can be recovered by the intranasal but not intraperitoneal administration of insulin

The hippocampus is closely associated with cognitive function, and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is one of the main areas of neurogenesis in the brain. To examine the adult neurogenesis level, we used the newborn neuron markers doublecortin (DCX), NeuroD and BrdU to evaluate the proliferation of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The western blot results presented in Fig. 2a suggested that the expression of NeuroD and DCX in the STZ + IN NS group was significantly decreased when compared with that in control mice. However, the intranasal administration of insulin almost recovered the neurogenesis decline to baseline in STZ mice, whereas no visible change was observed following the intraperitoneal administration. The other outcomes shown in Fig. 2b, c were similar: the number of Aβ-positive cells was significantly elevated, and the DCX-, NeuroD- and BrdU-labeled newborn cells in the dentate gyrus were markedly reduced in STZ mice. The results were very different between the groups treated with intranasal administration and intraperitoneal injection of insulin. The intranasal insulin-treated STZ mice showed marked improvements in the generation of newborn neurons and Aβ deposition, which were not observed in the intraperitoneally injected groups. This result indicated that STZ can decrease neurogenesis and induce Aβ deposition in the hippocampus, while intranasal insulin administration can markedly reverse the STZ effect.

Fig. 2.

Neurogenesis in the hippocampus among the four groups. a, b The expression and distribution of NeuroD and DCX were significantly decreased in the STZ + IN NS group compared with the control but significantly increased in the intranasal insulin treatment group compared with the STZ + IN NS group. Compared with STZ mice, almost no difference was observed in the intraperitoneal insulin treatment group. c The number of BrdU-labeled newborn cells suggested a similar result in the hippocampus. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 STZ + IN NS versus control; ##P < 0.01 STZ + IN ins versus STZ + IN NS; &P < 0.05 and &&P < 0.01 STZ + IP ins versus STZ + IN ins. Scale bar = 200 μm. DCX doublecortin, STZ streptozotocin, BrdU 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine

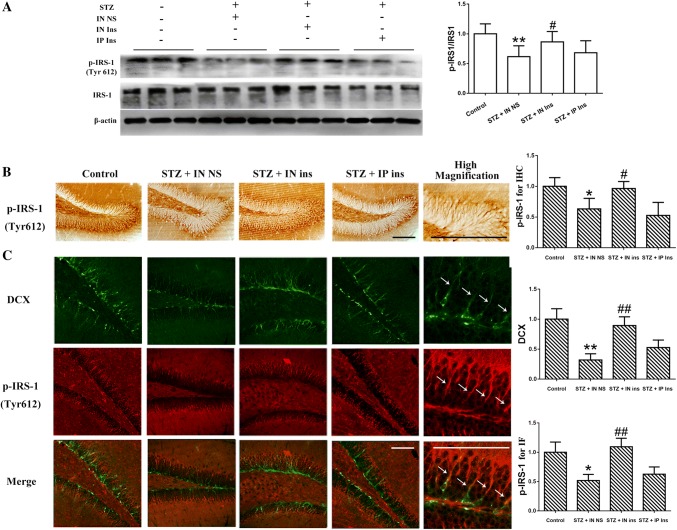

Intranasal insulin administration can reverse the effects of STZ on IRS-1 phosphorylation and reduce the activation of its associated pathway in the hippocampus

IRS-1 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that is activated by insulin. The western blot results in Fig. 3A indicated that the p-IRS-1 protein level was markedly decreased following STZ treatment in the hippocampus, and only intranasal insulin reversed this effect, suggesting that the insulin pathway in the hippocampus can be activated by intranasal insulin administration. It is well known that the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is the main area of neurogenesis in the brain; the p-IRS-1 and DCX distribution in the hippocampus was therefore detected to explore the association between the insulin pathway and neurogenesis. Immunohistochemistry showed that following I.C.V. STZ, the expression of p-IRS-1 in the dentate gyrus was significantly inhibited, and intranasal insulin treatment reversed the STZ influence (Fig. 3b). In addition, as shown in Fig. 3c, the coexpression of p-IRS-1 and DCX suggested that insulin receptor activation was positively correlated with the number of newborn cells in the dentate gyrus. However, p-IRS-1 did not fully colocalize with DCX (high-magnification image), which indicated that the p-IRS-1- and DCX-labeled neurons were partially different. Even so, each DCX-positive cell was found to have formed a synaptic connection with the p-IRS-1-positive cells (white arrow), suggesting that the insulin pathway may be involved in newborn neuron generation in an indirect way and may finally induce an improvement in cognitive function. Based on the western blotting and immunohistochemistry results, almost no change was observed in the p-IRS-1 of mice treated with intraperitoneal insulin compared with the STZ group. Neurogenesis in the hippocampus stayed below baseline in the control group. These results suggest that only the intranasal administration of insulin can reverse the STZ-induced decline in neurogenesis and insulin receptor activation.

Fig. 3.

Different IRS-1 activation in the four groups. a IRS-1 activation was decreased in the STZ + IN NS group, and no significant change was observed in the STZ + IP ins group. However, intranasal insulin treatment markedly increased the p-IRS-1 level in the STZ + IN ins group. b, c. The p-IRS-1 distribution in the hippocampus among the four groups was consistent with the western blot results. p-IRS-1-positive cells were found to be closely associated with the DCX-labeled newborn cells, although they did not fully colocalize. **P < 0.01 STZ + IN NS versus control; #P < 0.05 < 0.01 STZ + IN ins versus STZ + IN NS. Scale bar = 200 μm. STZ streptozotocin, IRS-1 insulin receptor substrate-1, DCX doublecortin

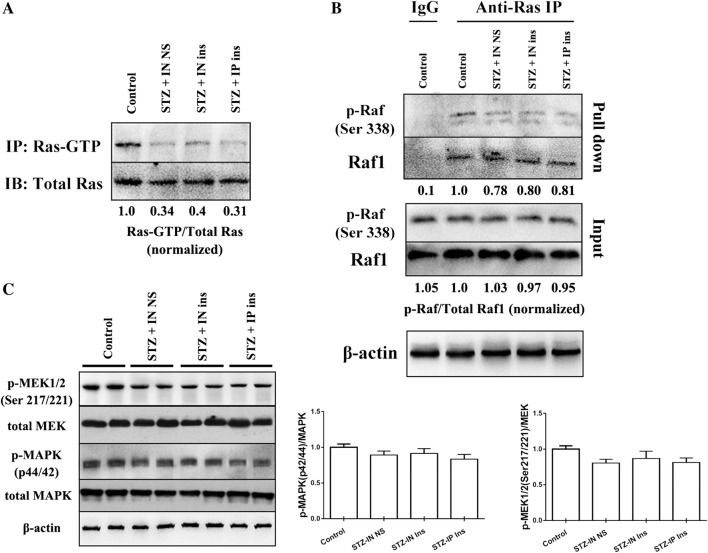

The PI3K-Akt-GSK3 pathway, but not the Ras-Raf1-MEK-MAPK, is involved in the mouse cognitive regulation induced by intranasal insulin

To further explore the role of the insulin pathway in the regulation of cognitive function, the activation of the insulin pathway (PI3K-Akt-GSK3β) was detected (Fig. 4a). A marked expression decline in p-PI3K, p-Akt and serine 9 of GSK3β (the inhibition site of GSK3β activation) was observed by western blot, which indicated that STZ treatment induced significant insulin resistance. Furthermore, by immunohistochemistry, the expression and distribution of serine 9-phosphorylated GSK3β were reduced significantly in the hippocampus of the STZ groups (Fig. 4b, upper diagrams). However, the intranasal administration of insulin largely reversed the insulin resistance caused by STZ and recovered the expression levels of p-PI3K, p-Akt and serine 9-phosphorylated GS3Kβ to baseline (Fig. 4a, b); this was also accompanied by an elevation of DCX abundance and distribution in the hippocampus of STZ-pretreated mice. DXC partially overlapped with serine 9-phosphorylated GSK3β in hippocampal neurons, which indicated that the phosphorylation of serine 9 in both adult and newborn neurons was reduced by STZ treatment (Fig. 4b, bottom diagrams). Additionally, a slight difference was observed in the insulin pathway activation and DCX expression in the intraperitoneally treated group when compared with STZ-treated mice. The intranasally treated mice exhibited not only a considerable improvement in insulin pathway activation of the hippocampus but also a notable elevation of neurogenesis and a high coexpression of DCX and serine 9-phosphorylated GSK3β in the hippocampus (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

The activation of the insulin signaling pathway in the four groups. a Compared with the control group, the activation of the insulin pathway in the STZ + IN NS group was decreased, and phosphorylation on serine 9 of GSK3β (the inhibition site of GSK3β activation) was significantly upregulated. Only the intranasal insulin treatment reversed the STZ effect. b The immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence results of serine 9 of GSK3β in the hippocampus led to a similar conclusion. The tendency of DCX-positive cells in STZ + IN NS and STZ + IN ins was highly consistent with the change in the phosphorylation of serine 9 of GSK3β, and DCX cells fully colocalized with serine 9-labeled cells. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 STZ + IN NS versus control; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 STZ + IN ins versus STZ + IN NS. Scale bar = 200 μm. STZ streptozotocin, GSK3β glycogen synthase kinase-3 β, DCX doublecortin

The Ras-Raf1-MEK-MAPK pathway was also tested in the present study. We first detected the Ras activation level after intranasal insulin treatment in STZ mice by the Active Ras Detection Kit (#8821, Cell Signaling Technology). The results suggested that the activated form Ras, Ras-GTP, significantly declined in STZ + IN NS mice. However, neither intranasal nor intraperitoneal administration of insulin influenced Ras activation (Fig. 5a). In addition, the downstream molecule Raf1, which is activated by binding to Ras, did not respond to insulin treatment (Fig. 5b). The activation of MEK and MAPK also showed no obvious change in the four groups (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

The activation level of the Ras-Raf-MEK-MAPK pathway in the four groups. a The expression of Ras was not different in the four groups, while the activation of Ras was significantly reduced in the three STZ-treated mice, and no significant changes were observed between the three groups. b Raf1 binding to Ras was decreased in the three STZ treatment groups, and no difference was observed between the three groups. c The expression and activation of MEK and MAPK was slightly reduced in the three STZ groups, and there was no significant difference between the three groups

To prove that the activation of the PI3K-Akt-GSK3 pathway in the hippocampus is the main molecular mechanism through which intranasal insulin reverses STZ-induced brain insulin resistance and cognitive function deficit, another four mouse model groups were designed, including control, STZ-IN NS, STZ-IN ins and STZ-IN ins + LY294002. LY294002 is a specific inhibitor of PI3K, one of the upstream molecules in the insulin pathway. The western blotting results (Fig. 6a) showed that IRS-1 activation in STZ-IN ins + LY294002 mice was not influenced by the inhibitor, but the downstream signaling of PI3K was obviously suppressed. Furthermore, DCX expression was decreased in inhibitor-treated mice, while Aβ expression was increased. The behavior of mice in each group (Fig. 6b–e) was highly consistent with the western blot results. The intranasal insulin-treated mice performed better in both training and testing tasks than STZ mice, while the progress in cognitive function was completely reversed by LY294002. Therefore, activating the brain insulin pathway to increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus and relieve brain insulin resistance may be the mechanism through which the intranasal administration of insulin enhances mouse learning and memory function. The intranasally treated mice exhibited not only a considerable improvement in the cerebral insulin level and insulin pathway activation but also a notable elevation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus and mouse cognitive function.

Fig. 6.

Insulin pathway inhibition blocks the intranasal insulin-induced improvement in cognitive function. a LY294002 blocked the activation of the downstream molecules of the IRS-1 pathway, decreased neurogenesis and promoted Aβ deposition. b–e LY294002 reversed the intranasal insulin-induced cognitive function improvement in STZ mice in the behavioral experiment. LY294002 significantly impaired the protective effect of intranasal insulin in the training task after 5 days. During the testing task, the target quadrant occupancy of the LY294002 group mice was markedly declined, and the swimming trajectories were more irregular than those in the STZ-IN ins group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 STZ + IN NS versus control; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 STZ + IN ins versus STZ + IN NS; &P < 0.05 and &&P < 0.01 STZ + IN ins + LY294002 versus STZ + IN ins. STZ streptozotocin, IRS-1 insulin receptor substrate-1

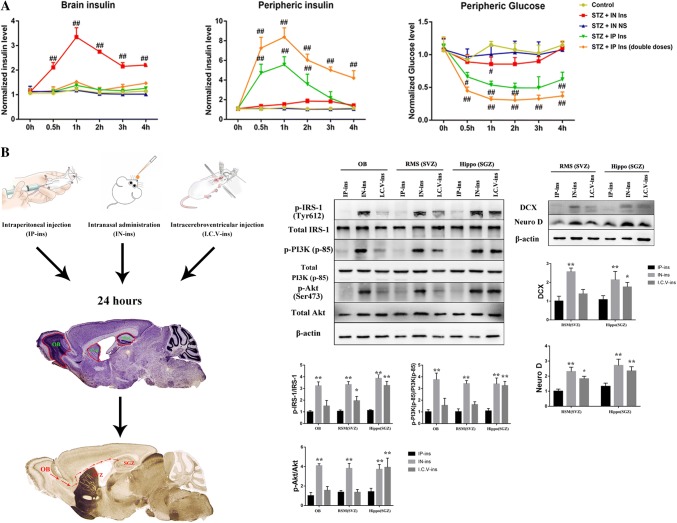

Intranasal administration of insulin can elevate the brain insulin concentration within hours without influencing the peripheral insulin level

To investigate the different effects of intranasal and intraperitoneal administration of insulin on brain function, the cerebral and peripheral insulin levels were further detected in each group. ELISA detection showed that there was almost no difference in the cerebral or peripheral insulin level between the control and STZ mice. Following the intranasal administration of insulin, the mice exhibited a considerably higher cerebral insulin level than the control and STZ groups within 0.5 h, peaking at 1 h, which was accompanied by little influence on peripheral insulin (Fig. 7a). A different outcome was observed in the intraperitoneal injection group. No difference was observed in the cerebral insulin level between the intraperitoneal and STZ groups, even though the mice in the STZ groups were administered a double dose of the drug. A dose-dependent elevation in peripheral insulin was observed in the intraperitoneal administration group (Fig. 7a). On the other hand, no difference was observed in the peripheral glucose concentration among the control, STZ and intranasal insulin groups. However, a dose-dependent decline in the peripheral glucose level was observed in the intraperitoneal administration group (Fig. 7a). According to these results, intranasal insulin administration can increase the brain insulin concentration but has almost no influence on the peripheral insulin or glucose concentration. Brain glucose is also an important indicator for the assessment of brain insulin resistance. However, the glucose concentration in brain homogenate is difficult to verify (intracellular or extracellular), so we did not show this result in this study. Thus, nasal administration allows insulin to enter the brain effectively, having little effect on the periphery.

Fig. 7.

Different insulin and glucose concentrations in the periphery and brain and insulin pathway activation in OB, SVZ and SGZ. a ELISA of cerebral and peripheral insulin and glucose concentrations in each group. Compared with that in the control group, the insulin concentration in the two STZ + IP ins groups was not significantly increased in the brain but was in the periphery after 0.5 h. Brain insulin level in the STZ + IN ins group was markedly increased within 0.5 h, peaking at 1 h, with almost no impact on the periphery. No difference was observed in the brain or periphery between the STZ + IN NS group and the control. In addition, the peripheral glucose level was obviously decreased in the IP ins group. Compared to the control, no statistically significant difference in the glucose concentration was observed in the IN ins group over 4 h. b Mice were divided into three groups: IP-ins, IN-ins and I.C.V.-ins. After 24 h, the tissues in OB, SVZ and SGZ were harvested for further western blot detection. Compared with the IP-ins group, IN-ins mice had significantly increased IRS-1-PI3K-Akt pathway activation in the OB, SVZ and SGZ areas. Insulin pathway activation in the I.C.V.-ins group was only elevated in SGZ, and no obvious difference was observed in OB or SVZ. The DCX and NeuroD expression in SGZ was enhanced in both the IN-ins and I.C.V.-ins mice, and only the IN-ins mice showed marked changes in SVZ when compared with the IP-ins group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, compared to IP-ins; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 compared to control. The section image of the mouse brain is quoted from “The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates” (Franklin and Paxinos 2008)

Intranasal insulin administration can enhance insulin pathway activation in the hippocampus and subependymal ventricular zone through the OB-SVZ-SGZ axis

To further explore the potential mechanism of intranasal administration, we tested the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt activation level in the olfactory bulb (OB), subgranular zone (SGZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ), which are connected by the rostral migratory stream (RSM) (Fig. 7b). RMS is a special migration route that allows the neuronal precursors generated from SVZ and SGZ to migrate to OB. SVZ, located on the sidewall of the lateral ventricle, is one area of neurogenesis in the adult brain, and SGZ is the other region, located in the hippocampus. In our study, compared with the IP-ins mice, the IN-ins group had significantly enhanced IRS-1-PI3K-Akt pathway activation in OB, SVZ and SGZ. However, the I.C.V.-ins elevated the activation of the insulin pathway in SGZ, but not in OB or SVZ. DCX and NeuroD labeling also indicated that both IN-ins and I.C.V.-ins increased the neurogenesis level in SGZ, but only IN-ins influenced neurogenesis in SVZ (Fig. 7b). IP insulin treatment showed no significant effect in the three regions. Thus, intranasal insulin can increase insulin pathway activation in RSM, including OB, SVZ and SGZ.

Discussion

Brain insulin resistance plays an important role in cognitive dysfunction

Insulin resistance is a pathophysiological process that plays a significant role in the development of metabolic diseases and is associated with neurodegeneration. This dysfunction is reflected by cells failing to respond to insulin receptor-activated signaling in sensitive tissue (Newsholme et al. 2014) and brain tissue (Bomfim et al. 2012; Talbot et al. 2012). Insulin receptor substrate-1 is abundantly distributed in functional areas of the brain, including the hippocampus (Dore et al. 1997), and its associated pathway has been proven to be involved in the modulation of memory and learning, synaptic plasticity and neuronal stem cell proliferation (Zhao et al. 2010; Chiu et al. 2008; Cohen et al. 2007; Apostolatos et al. 2012). The absence of insulin or its receptor would lead to hippocampal neuron dysfunction and, in turn, to cognitive deficit-associated diseases (Verdile et al. 2015). STZ is a glucose analog that can cause a decline in insulin-dependent glucose cellular uptake by GLUT-2, which is not widely distributed in the brain, except in the pyramidal neurons in the neocortex and hippocampus (CA3 and dentate gyrus) (Lenzen 2008; Talbot and Wang 2014). I.C.V. injection of STZ is an efficient way to establish brain insulin resistance mouse models and induce related cognitive dysfunctions (Chen et al. 2013; Park et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018). It can downregulate the insulin level (Kamat 2015), decrease brain glucose utilization (Duelli et al. 1994; Grieb 2016) and impair insulin receptor function in the brain (Hoyer et al. 2000), causing free radical generation, alteration of glycogen synthase kinase (Kamat 2015), expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Kumar et al. 2017) and decreased tissue sensitivity to the action of insulin (Grieb 2016), which has been defined as an insulin-resistant brain state (Frisardi et al. 2010; Correia et al. 2011).

In the present study, a significant decline in learning and memory function was observed in the Morris water maze behavioral tests undertaken by I.C.V. STZ mice. The DXC, NeuroD and BrdU expression suggested that the neurogenesis level was much lower in I.C.V. STZ mice than that in control mice. Aβ was clearly deposited in the hippocampus of the STZ-treated mice, and the activation of IRS-1 was obviously decreased. Furthermore, the immunofluorescence results revealed that p-IRS-1 was partly colocalized with DCX, suggesting that the newborn neurons exhibited high insulin pathway activation and that the insulin signaling pathway may be involved in neurogenesis. The results therefore indicate that the insulin pathway was downregulated by STZ treatment and that I.C.V. STZ administration can establish successful cognitive deficit and brain insulin resistance mouse models.

Intranasal insulin improves cognitive function and neurogenesis in the hippocampus by the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt-GSK3β pathway

A crucial hormone in the brain, insulin is responsible for many functions. It affects energy expenditure, glucose homeostasis, and neurogenesis (Blazquez et al. 2014). A previous study has indicated that AD is twice as frequent in diabetic patients, which may be because central insulin resistance is a major stimulus for the development of AD (Blazquez et al. 2014). Voluntary exercise can improve adult neurogenesis and cognitive function by enhancing the activation of the insulin pathway and further promoting adult neurogenesis in mice (Zang et al. 2017). Oxaloacetate can reduce inflammation and stimulate neurogenesis by activating brain mitochondrial biogenesis and enhancing insulin signaling (Wilkins et al. 2014). Thus, improving brain insulin resistance to improve cognitive dysfunction is an important issue in AD treatment.

Intranasal administration can improve insulin receptor dysfunction, neuroinflammation, amyloidogenesis, and memory impairment in rats (Rajasekar et al. 2017). In clinical studies, it has been proven to improve cognition for adults with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia (Claxton et al. 2015) and to function as an effective therapeutic alternative for children who are exposed to poorly controlled gestational diabetes to reverse their central pathology and cognitive impairment (Ramos-Rodriguez et al. 2017). In the present study, compared with STZ mice, the intranasal insulin treatment group showed highly improved learning and memory functions in the Morris water maze test. The expression and distribution of the newborn neuron markers DCX, NeuroD and BrdU were also significantly increased, and Aβ expression was markedly reduced. On the other hand, the intraperitoneal insulin-injected mice did not show any obvious changes in learning and memory function or neurogenesis level compared with the STZ group. This finding indicates that intranasal insulin administration can improve animal cognitive function and neurogenesis in brain insulin resistance mice.

IRS-1 is a substrate of the insulin receptor. It is widely distributed in the neuronal membrane of the central nervous system (Talbot et al. 2012; Unger and Betz 1998), especially in the hippocampus (Belfiore et al. 2009; van der Heide et al. 2006). IRS-1-PI3K-Akt-GSK3β is a major signaling pathway that insulin induces and is involved in cell proliferation and metabolism, including neurogenesis and the maturation of newborn neurons (Wu et al. 2013; Bruel-Jungerman et al. 2009). GSK3β is a key downstream molecule of the insulin pathway that also functions as a crucial regulatory factor for the phosphorylation of tau and Aβ deposition (Tanaka et al. 2000). The insulin pathway can downregulate GSK3β activation by enhancing the phosphorylation of serine 9 to block the hyperphosphorylation of tau and Aβ deposition (Hong et al. 2014; Cheng et al. 2015). In our study, it was found that the distribution and activation levels of IRS-1 and its downstream molecules, PI3K, Akt and GSK3β, were significantly decreased following STZ treatment in the hippocampus. Intranasal insulin obviously reversed STZ-induced insulin resistance and recovered the activation of the IRS-1 signaling pathway in the brain. However, intraperitoneal insulin had no influence on the brain insulin concentration or the activation of the insulin pathway compared with in the STZ groups. The expression of newborn neuron markers was downregulated in STZ mice and largely returned to baseline after intranasal insulin administration. These findings indicate that neurogenesis is enhanced by intranasal insulin treatment and that the insulin pathway is closely connected with neurogenesis in hippocampal neurons.

The activation of the Ras-Raf1-MEK-MAPK pathway was also detected. It is another downstream pathway of insulin and is involved in inflammation, proliferation, differentiation and cell growth (D’Oria et al. 2017). Ras is a member of the small GTPase family, and it can be activated by IRS-1 to form Ras-GTP and further bind to Raf1 to further phosphorylate MEK and MAPK. In our study, STZ treatment lowered the Ras-GTP level (Ritt et al. 2016). However, neither intranasal nor intraperitoneal administration enhanced Ras activation. Raf1, MEK and MAPK also showed no significant difference between the two insulin treatment groups, which means that the Ras-Raf1-MEK-MAPK pathway may not have a critical influence on cognitive function.

To further prove that the activation of the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt-GSK3β pathway is the primary mechanism through which intranasal insulin enhances cognitive function, we used the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 to suppress the activation of the insulin pathway. The results showed that LY294002 can decrease the activation of the insulin pathway in intranasal insulin mice. The inhibitor also had a negative impact on the behavior and neurogenesis levels of intranasal insulin-treated mice. In addition, DCX expression declined, but the deposition of Aβ was elevated in the LY294002 group. These results further confirm that intranasal insulin administration can enhance cognitive function and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of mice with brain insulin resistance by activating the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt pathway but not the Ras-Raf1-MEK-MAPK pathway. Therefore, intranasal insulin administration may be a highly efficient way of supplying insulin to the brain.

Intranasal insulin elevates the brain insulin level to activate the insulin pathway, which may work through the OB-SVZ-SGZ axis in STZ mice

According to a previous study, intraperitoneal insulin can significantly reduce insulin resistance in peripheral tissues but has little effect on the brain (Gray et al. 2014). This may be because insulin, as a macromolecule protein, is allowed into the cerebral circulation through a saturable transport mechanism, making it hard for it to freely pass through the blood–brain barrier (Banks 2012). To obtain an effective brain insulin concentration, a high dose of insulin needs to be peripherally administered, which may cause serious adverse reactions, such as hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia (Shanik et al. 2008). In the present study, the brain insulin level in intranasally treated mice was considerably higher than that in the STZ group, with almost no influence observed on the peripheral insulin or glucose level. However, even following the administration of a double dose of insulin by intraperitoneal injection, only a slight change was observed in the brain insulin level when compared to the STZ groups, while the levels of peripheral insulin and glucose were significantly elevated in the intraperitoneally treated mice. Thus, intranasal administration may have some unique mechanism of transmitting insulin.

The olfactory bulb is the primary center of olfaction. It can regulate the animal’s sensitivity to smells, which explains its larger size in rodent than in human brains (Curtis et al. 2007). According to a previous study, the adult neurogenesis regions, as well as the SVZ and SGZ, are closely associated with the olfactory bulb (Zhao et al. 2008). The neuronal precursors that originate in the subventricular zone of the brain can migrate to the main olfactory bulb through a specialized migratory route, the RSM, which may function as the structural basis for the connection of olfaction and cognition. In our study, we hypothesized that intranasal administration transmits insulin through RSM and regulates neuronal function in the hippocampus. By measuring the activation levels of the IRS-1-PI3K-Akt-GSK3β pathway in the OB, SVZ and SGZ regions, we compared the influence of intranasal, intraperitoneal and I.C.V. administration on the insulin signaling pathway in RSM. The results showed that only intranasal insulin treatment increased insulin pathway activation in those three regions. The I.C.V. insulin had little effect on OB and SVZ neurons, and almost no changes were observed in the whole RSM in intraperitoneal insulin-injected mice. Thus, the OB-SVZ-SGZ axis may be the mechanism by which intranasal administration delivers insulin to the hippocampus.

Conclusion

Intranasal insulin can increase the concentration of insulin in the brain without affecting the peripheral insulin level, thus increasing the brain insulin level more efficiently and avoiding adverse effects caused by peripheral administration. Following intranasal administration, IRS-1-PI3K-Akt pathway activation and neurogenesis are enhanced in the hippocampus, leading to reversal of cognitive dysfunction. The OB-SVZ-SGZ axis might be the mechanism through which intranasal administration delivers insulin to the hippocampus.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81860244); Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2018GXNSFAA281051); the Basic Ability Enhancement Program for Young and Middle-age Teachers of Guangxi (Grant No. 2017KY0516).

Abbreviations

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

Amyloid beta

- IRS-1

Insulin receptor substrate-1

- PI3K

PI-3 kinase

- GSK3

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- IDE

Insulin-degrading enzyme

- IN

Intranasal administration

- IP

Intraperitoneal administration

- Ins

Insulin

- NS

Normal saline

- I.C.V.

Intracerebroventricular

- IRBS

Insulin-resistant brain state

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- DCX

Doublecortin

- BrdU

5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine

- GLUT2

Glucose transporter 2

- SVZ

Subependymal ventricular zone

- SGZ

Subgranular zone

- OB

Olfactory bulb

- RMS

Rostral migratory stream

Author contributions

CDJ designed experiments. HL, LJT, CSG, YMJ, CG and YFM performed experiments. CSG, QTL and XLM contributed to the statistical analyses and interpretation. HL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmed S, Mahmood Z, Zahid S. Linking insulin with Alzheimer’s disease: emergence as type III diabetes. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(10):1763–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolatos A, Song S, Acosta S, Peart M, Watson JE, Bickford P, et al. Insulin promotes neuronal survival via the alternatively spliced protein kinase CdeltaII isoform. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(12):9299–9310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA. Brain meets body: the blood–brain barrier as an endocrine interface. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4111–4119. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Freude S, Zemva J, Stohr O, Krone W, Schubert M. Chronic peripheral hyperinsulinemia has no substantial influence on tau phosphorylation in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 2012;516(2):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology and disease. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):586–623. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez E, Velazquez E, Hurtado-Carneiro V, Ruiz-Albusac JM. Insulin in the brain: its pathophysiological implications for states related with central insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5:161. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomfim TR, Forny-Germano L, Sathler LB, Brito-Moreira J, Houzel JC, Decker H, et al. An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse brain from defective insulin signaling caused by Alzheimer’s disease-associated Abeta oligomers. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(4):1339–1353. doi: 10.1172/JCI57256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel-Jungerman E, Veyrac A, Dufour F, Horwood J, Laroche S, Davis S. Inhibition of PI3K-Akt signaling blocks exercise-mediated enhancement of adult neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liang Z, Blanchard J, Dai CL, Sun S, Lee MH, et al. A non-transgenic mouse model (icv-STZ mouse) of Alzheimer’s disease: similarities to and differences from the transgenic model (3xTg-AD mouse) Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47(2):711–725. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Deng Y, Zhang B, Gong CX. Deregulation of brain insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30(2):282–294. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PW, Chen YY, Cheng WH, Lu PJ, Chen HH, Chen BR, et al. Wnt signaling regulates blood pressure by downregulating a GSK-3beta-mediated pathway to enhance insulin signaling in the central nervous system. Diabetes. 2015;64(10):3413–3424. doi: 10.2337/db14-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SL, Chen CM, Cline HT. Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58(5):708–719. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton A, Baker LD, Hanson A, Trittschuh EH, Cholerton B, Morgan A, et al. Long-acting intranasal insulin detemir improves cognition for adults with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2015;44(3):897–906. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AC, Tong M, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor resistance with neurodegeneration in an adult chronic ethanol exposure model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(9):1558–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia SC, Santos RX, Perry G, Zhu X, Moreira PI, Smith MA. Insulin-resistant brain state: the culprit in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease? Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(2):264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Newcomer J, Kanne S, Dagogo-Jack S, Cryer P, Sheline Y, et al. Memory improvement following induced hyperinsulinemia in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17(1):123–130. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)02002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, Minoshima S, Watson GS, Claxton A, et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):29–38. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. The effect of neurodegenerative diseases on the subventricular zone. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(9):712–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Jahrling JB, Denner L. Insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72(Pt A):92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Kar S, Rowe W, Quirion R. Distribution and levels of [125I]IGF-I, [125I]IGF-II and [125I]insulin receptor binding sites in the hippocampus of aged memory-unimpaired and -impaired rats. Neuroscience. 1997;80(4):1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Oria R, Laviola L, Giorgino F, Unfer V, Bettocchi S, Scioscia M. PKB/Akt and MAPK/ERK phosphorylation is highly induced by inositols: novel potential insights in endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017;10:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duelli R, Schrock H, Kuschinsky W, Hoyer S. Intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin induces discrete local changes in cerebral glucose utilization in rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1994;12(8):737–743. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KB, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Capurso C, Imbimbo BP, Vendemiale G, Seripa D, et al. Is insulin resistant brain state a central feature of the metabolic-cognitive syndrome? J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2010;21(1):57–63. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SM, Meijer RI, Barrett EJ. Insulin regulates brain function, but how does it get there? Diabetes. 2014;63(12):3992–3997. doi: 10.2337/db14-0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieb P. Intracerebroventricular streptozotocin injections as a model of Alzheimer’s disease: in search of a relevant mechanism. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1741–1752. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9132-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunblatt E, Salkovic-Petrisic M, Osmanovic J, Riederer P, Hoyer S. Brain insulin system dysfunction in streptozotocin intracerebroventricularly treated rats generates hyperphosphorylated tau protein. J Neurochem. 2007;101(3):757–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Gan J, Tan T, Tian X, Wang G, Ng KT. Neonatal exposure of ketamine inhibited the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation without impairing the spatial memory of adult rats. Cogn Neurodyn. 2018;12(4):377–383. doi: 10.1007/s11571-018-9474-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong HJ, Kang W, Kim DG, Lee DH, Lee Y, Han CH. Effects of resveratrol on the insulin signaling pathway of obese mice. J Vet Sci. 2014;15(2):179–185. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2014.15.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer S, Lee SK, Loffler T, Schliebs R. Inhibition of the neuronal insulin receptor. An in vivo model for sporadic Alzheimer disease? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:256–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat PK. Streptozotocin induced Alzheimer’s disease like changes and the underlying neural degeneration and regeneration mechanism. Neural Regener Res. 2015;10(7):1050–1052. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.160076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Kaur D, Bansal N. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) prevents development of STZ-ICV induced dementia in rats. Pharmacogn Mag. 2017;13(Suppl 1):S10–S15. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.203974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S. The mechanisms of alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51(2):216–226. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Hyperinsulinemia and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1187–1192. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000140292.04932.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Corraliza J, Wong H, Mazzella MJ, Che S, Lee SH, Petkova E, et al. Brain-wide insulin resistance, tau phosphorylation changes, and hippocampal neprilysin and amyloid-beta alterations in a monkey model of type 1 diabetes. J Neurosci. 2016;36(15):4248–4258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4640-14.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik B, Nirwane A, Majumdar A. Pterostilbene ameliorates intracerebroventricular streptozotocin induced memory decline in rats. Cogn Neurodyn. 2017;11(1):35–49. doi: 10.1007/s11571-016-9413-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Ohyagi Y, Imamura T, Yanagihara YT, Iinuma KM, Soejima N, et al. Apomorphine therapy for neuronal insulin resistance in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2017;58(4):1151–1161. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Cruzat V, Arfuso F, Keane K. Nutrient regulation of insulin secretion and action. J Endocrinol. 2014;221(3):R105–R120. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kim YH, Nam GH, Choe SH, Lee SR, Kim SU, et al. Quantitative expression analysis of APP pathway and tau phosphorylation-related genes in the ICV STZ-induced non-human primate model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):2386–2402. doi: 10.3390/ijms16022386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Folstein MF. Insulin, insulin-degrading enzyme and amyloid-beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease: review and hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(2):190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekar N, Nath C, Hanif K, Shukla R. Intranasal insulin administration ameliorates streptozotocin (ICV)-induced insulin receptor dysfunction, neuroinflammation, amyloidogenesis, and memory impairment in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(8):6507–6522. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Rodriguez JJ, Sanchez-Sotano D, Doblas-Marquez A, Infante-Garcia C, Lubian-Lopez S, Garcia-Alloza M. Intranasal insulin reverts central pathology and cognitive impairment in diabetic mother offspring. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0198-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritt DA, Abreu-Blanco MT, Bindu L, Durrant DE, Zhou M, Specht SI, et al. Inhibition of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway signaling by a stress-induced phospho-regulatory circuit. Mol Cell. 2016;64(5):875–887. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovic-Petrisic M, Osmanovic J, Grunblatt E, Riederer P, Hoyer S. Modeling sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: the insulin resistant brain state generates multiple long-term morphobiological abnormalities including hyperphosphorylated tau protein and amyloid-beta. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2009;18(4):729–750. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaoka T, Wada T, Tsuneki H. Insulin resistance and cognitive function. Nihon rinsho Jpn J Clin Med. 2014;72(4):633–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanik MH, Xu Y, Skrha J, Dankner R, Zick Y, Roth J. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S262–S268. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Wang HY. The nature, significance, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analog treatment of brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2014;10(1 Suppl):S12–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Wang HY, Kazi H, Han LY, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(4):1316–1338. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Tsujio I, Nishikawa T, Shinosaki K, Kudo T, Takeda M. Significance of tau phosphorylation and protein kinase regulation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S18–S24. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200000001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JW, Betz M. Insulin receptors and signal transduction proteins in the hypothalamo-hypophyseal system: a review on morphological findings and functional implications. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13(4):1215–1224. doi: 10.14670/HH-13.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide LP, Ramakers GM, Smidt MP. Insulin signaling in the central nervous system: learning to survive. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79(4):205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdile G, Keane KN, Cruzat VF, Medic S, Sabale M, Rowles J, et al. Inflammation and oxidative stress: the molecular connectivity between insulin resistance, obesity, and Alzheimer’s disease. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:105828. doi: 10.1155/2015/105828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Wang C, Liu L, Li S. Protective effects of evodiamine in experimental paradigm of Alzheimer’s disease. Cogn Neurodyn. 2018;12(3):303–313. doi: 10.1007/s11571-017-9471-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins HM, Harris JL, Carl SM, Lezi E, Lu J, Eva Selfridge J, et al. Oxaloacetate activates brain mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances the insulin pathway, reduces inflammation and stimulates neurogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(24):6528–6541. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YY, Wang X, Tan L, Liu D, Liu XH, Wang Q, et al. Lithium attenuates scopolamine-induced memory deficits with inhibition of GSK-3beta and preservation of postsynaptic components. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2013;37(3):515–527. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ma D, Wang Y, Jiang T, Hu S, Zhang M, et al. Intranasal insulin ameliorates tau hyperphosphorylation in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. J Alzheimer’s Dis JAD. 2013;33(2):329–338. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang J, Liu Y, Li W, Xiao D, Zhang Y, Luo Y, et al. Voluntary exercise increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis by increasing GSK-3beta activity in mice. Neuroscience. 2017;23(354):122–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132(4):645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Wu X, Xie H, Ke Y, Yung WH. Permissive role of insulin in the expression of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of immature rats. Neuro-Signals. 2010;18(4):236–245. doi: 10.1159/000324040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]