Abstract

Peptidyl-prolyl isomerization is an important post-translational modification of protein because proline is the only amino acid that can stably exist as cis and trans, while other amino acids are in the trans conformation in protein backbones. This makes prolyl isomerization a unique mechanism for cells to control many cellular processes. Isomerization is a rate-limiting process that requires a peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase (PPIase) to overcome the energy barrier between cis and trans isomeric forms. Pin1, a key PPIase in the cell, recognizes a phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro motif to catalyze peptidyl-prolyl isomerization in proteins. The significance of the phosphorylation-dependent Pin1 activity was recently highlighted for isomerization of ATR (ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related). ATR, a PIKK protein kinase, plays a crucial role in DNA damage responses (DDR) by phosphorylating hundreds of proteins. ATR can form cis or trans isomers in the cytoplasm depending on Pin1 which isomerizes cis-ATR to trans-ATR. Trans-ATR functions primarily in the nucleus. The cis-ATR, containing an exposed BH3 domain, is anti-apoptotic at mitochondria by binding to tBid, preventing activation of pro-apoptotic Bax. Given the roles of apoptosis in many human diseases, particularly cancer, we propose that cytoplasmic cis-ATR enables cells to evade apoptosis, thus addicting cancer cells to cis-ATR formation for survival. But in normal DDR, a predominance of trans-ATR in the nucleus coordinates with a minimal level of cytoplasmic cis-ATR to promote DNA repair while preventing cell death; however, cells can die when DNA repair fails. Therefore, a delicate balance/equilibrium of the levels of cis- and trans-ATR is required to ensure the cellular homeostasis. In this review, we make a case that this anti-apoptotic role of cis-ATR supports oncogenesis, while Pin1 that drives the formation of trans-ATR suppresses tumor growth. We offer a potential, novel target that can be specifically targeted in cancer cells, without killing normal cells, to significantly reduce the adverse effects usually seen in cancer treatment. We also raise important issues regarding the roles of phosphorylation-dependent Pin1 isomerization of ATR in diseases and propose areas of future studies that would shed more understanding on this important cellular mechanism.

Keywords: cytoplasmic ATR, Pin1, antiapoptotic ATR, apoptosis, prolyl isomerization, cancer, cis and trans

Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerization of Proteins and Pin1

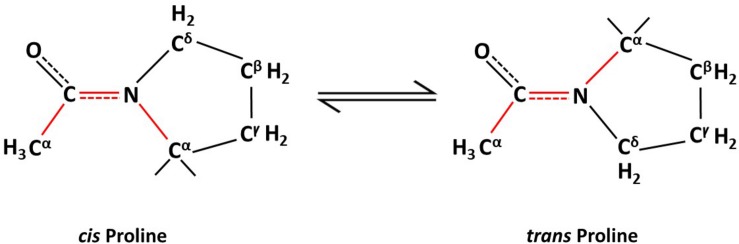

Individual proteins may perform multiple functions and have evolved to evade unnecessary degradation. These differing functions and survival skills involve posttranslational modifications of proteins. Apart from protein function, post-translational modifications (PTMs) of proteins also can affect their sub-cellular location, stability and inter-molecular interactions with other proteins (Gothel and Marahiel, 1999; Lu and Zhou, 2007; Lu et al., 2007). Of the various types of PTMs such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, and so on, peptidyl isomerization of a protein is a unique type of PTM (Tanford, 1968). Peptidyl isomerization is the reversible transformation of a molecule between cis and trans isomeric forms, such that the peptide or protein can exist in two distinct geometric conformations, cis and trans (Figure 1). This modification causes no change in the molecular weight of the peptide or protein; hence, the inability to detect this change by mass spectrometry; however, isomerization, especially of a proline residue, alters the affected protein’s structure. The biological significance of prolyl isomerization, as compared to the other 19 non-proline amino acids, is that all non-proline amino acids are naturally stable in trans isomeric form whereas proline can be in either the cis or the trans isoform at the amide bond of proline with the preceding amino acid (Fischer and Schmid, 1990; Hinderaker and Raines, 2003; Song et al., 2006; Craveur et al., 2013; Figure 1). Thus, peptidyl isomerization of protein refers mostly to peptidylprolyl isomerization.

FIGURE 1.

Non-enzymatic proline isomerization within proteins is a slow, rate-limiting process in the folding pathway.

Most amino acid residues within a folded protein are thermodynamically more stable in the trans form (Stewart et al., 1990; Schmidpeter and Schmid, 2015). However, proline has the unique ability to exist as a cis or a trans residue in a protein’s structural backbone as the side chain of proline forms part of the backbone of protein (Fischer and Schmid, 1990; Hinderaker and Raines, 2003; Song et al., 2006; Craveur et al., 2013). This potential to switch between isomeric forms (Figure 1) via isomerization allows proline to act as a molecular switch that affects the protein’s structure and, hence, its physiological functions. The isomerization naturally occurs slowly and is rate limiting in the protein folding process. Hence, enzymes, such as peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases (PPIases) are required to overcome existing high-energy barriers between these protein isomers and to stabilize the transition between cis/trans isoforms. Protein isomerization is involved in many cellular processes such as apoptosis (Follis et al., 2015; Hilton et al., 2015), mitosis (Lu et al., 1996; Yaffe et al., 1997; Rippmann et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2014), cell signaling (Brazin et al., 2002; Sarkar et al., 2007; Toko et al., 2013), ion channel gating (Antonelli et al., 2016), amyloidogenesis (Eakin et al., 2006), DNA damage repair (Steger et al., 2013), and neurodegeneration (Pastorino et al., 2006; Grison et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2012; Sorrentino et al., 2014).

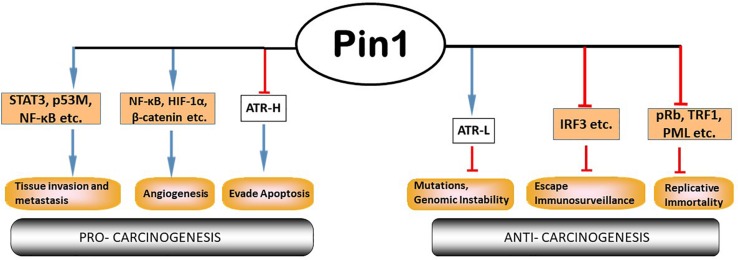

Pin1 is a member in the parvulin family of peptidyl prolyl isomerases (PPIases); it can catalyze proline isomerization only at a phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro (pSer/pThr-Pro) motif (Lu et al., 1996, 2007; Lu and Zhou, 2007). Structurally, Pin1 consists of an N-terminal WW protein interaction domain which binds its substrate at the pSer/pThr-Pro motif, a central flexible linker and a C-terminal PPIase domain to catalyze proline isomerization (Lu et al., 1996). Pin1’s activity, stability, subcellular location and substrate binding can be regulated by its own PTMs, including Serine 71 phosphorylation by DAPK1 (inactivates Pin1; Lee et al., 2011; Hilton et al., 2015), ubiquitination (Eckerdt et al., 2005) oxidation (Chen et al., 2015), and sumoylation (Chen et al., 2013). Pin1 is involved in regulating multiple cellular processes including cell cycle transit and division (Rippmann et al., 2000), differentiation and senescence (Hsu et al., 2001; Toko et al., 2014) and apoptosis (Pinton et al., 2007; Follis et al., 2015; Hilton et al., 2015). To perform these cellular functions, Pin1 binds to many substrates within the cell (Figure 2). These substrates include proteins involved in cell cycle regulation (p53, cyclin E), transcriptional regulation (E2F, Notch1), DNA damage responses (DDR), and so forth (Lin et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018). Pin1 expression and activity have been implicated in many diseases from neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Pastorino et al., 2006; Kesavapany et al., 2007; Nakamura et al., 2012, 2013), autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (Wei et al., 2016), to cancer (Ayala et al., 2003; Ryo et al., 2003; He et al., 2007; Yeh and Means, 2007; Finn and Lu, 2008; Nakamura et al., 2013; Lu and Hunter, 2014; Lin et al., 2015; Zhou and Lu, 2016; Chen et al., 2018; El Boustani et al., 2018; Nakatsu et al., 2019), etc. ATR (ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related) protein, a master regulator and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K-like) protein kinase in DDR (Zou and Elledge, 2003; Cimprich and Cortez, 2008; Flynn and Zou, 2011), was recently reported to be a substrate of Pin1 for prolyl isomerization (Hilton et al., 2015). Given that ATR phosphorylates hundreds of proteins in response to DNA damage (Matsuoka et al., 2007), isomerization of ATR by Pin1 represents a new paradigm in understanding Pin1’s biological activities, which is the focus of this article (Figures 2, 3).

FIGURE 2.

Pin1 participates extensively in multiple cellular processes involved in cancer. Pin1 has many cellular substrates that participate in the multi-step tumor development processes. Pin1’s roles can be contradictory: pro- or anti-tumor. Pin1 inhibits formation of cis-ATR and deprives the cell of cis-ATR’s anti-apoptotic role at the mitochondria, while promoting the formation of trans-ATR in the nucleus where it is important for repair of genotoxic stress to prevent mutations and maintain genome stability. Modified from Chen et al. (2018).

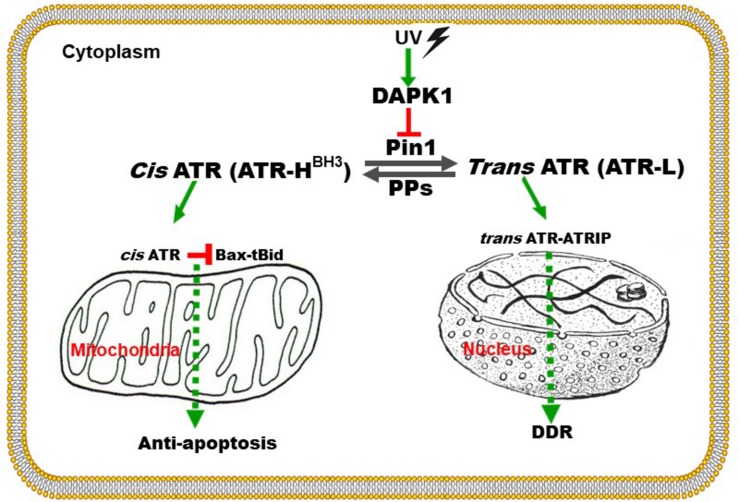

FIGURE 3.

Graphical representation of the proposed mechanism by which ATR plays a direct anti-apoptotic function at the mitochondria. UV damage inactivates Pin1’s isomerization of ATR in the cytoplasm. Cis-ATR (ATR-H) then accumulates and binds to and sequesters t-Bid at the outer mitochondria membrane. Without tBid, Bax and Bak fail to polymerize, thus cis-ATR inhibits cytochrome c release and apoptosis. Trans-ATR (ATR-L) is the dominant isomer in the nucleus where it interacts with ATRIP, RPA and chromatin in the DNA damage repair (DDR) response. PPs (protein phosphatases) can dephosphorylate the Pin1 recognition motif and promote formation of cis-ATR (to be published elsewhere). Modified from Hilton et al. (2015).

Posttranslational Modifications of ATR for Its Respective Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Functions

ATR is a key DDR protein kinase that the cell employs to sense replicative stress and DNA damage. Following replication arrest and formation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), RPA coats the ssDNA and recruits ATR-ATRIP complex via ATRIP (ATR interacting protein). ATRIP is the nuclear partner of ATR and carries bound ATR along to the DNA damage site, where ATR is autophosphorylated at its T1989 residue (Cortez et al., 2001). This phosphorylated residue serves as a docking site for TopBP1 to significantly enhance the activation of ATR’s kinase activity (Burrows and Elledge, 2008; Mordes et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011). ATR in turn activates several key downstream proteins, including p53 and other checkpoint kinases such as Chk1, leading to an S-phase cell cycle arrest for proper repair of the DNA damage or apoptosis in case of excessive damage (Cortez et al., 2001; Zou and Elledge, 2003; Sancar et al., 2004; Mordes and Cortez, 2008; Ciccia and Elledge, 2010; Nam and Cortez, 2011; Saldivar et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2019).

Recently, ATR was found to function in the cytoplasm and was described to play an important anti-apoptotic role directly at the mitochondria, independent of nuclear ATR and its kinase activity (Hilton et al., 2015). In contrast to nuclear ATR which always remains in trans form in complexing with ATRIP, cytoplasmic ATR in the absence of ATRIP exists in two forms, cis and trans, the existence of which depends on changing just one peptide bond orientation in ATR by prolyl isomerization. The balance between cis and trans cytoplasmic forms is regulated by Pin1, which catalyzes the conversion of cis-ATR to trans-ATR by recognizing the phosphorylated Serine 428-Proline 429 residues (pS428-P429) in the N-terminal region of ATR (Figure 3; Hilton et al., 2015). The activity of Pin1 favors the formation of trans-ATR, but inactivation of Pin1 by DAPK1 kinase upon DNA damage promotes cis-ATR accumulation at the mitochondria as cis-ATR appears to be naturally stable in cells. It is proposed that unlike its trans isoform, cis-ATR has an exposed BH3-like domain that allows it to bind to the pro-apoptotic tBid protein at the mitochondria. This binding prevents tBid from activating Bax-Bak polymerization which is necessary for the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Hence, cis-ATR performs an anti-apoptotic role that allows the cells to survive long enough to repair its damaged DNA (Figure 3). However, this can be a double-edged sword that can play a role in carcinogenesis as discussed below. The newly discovered BH3 domain, a hallmark of apoptotic proteins, in ATR defines cis-ATR’s role in the apoptosis pathway (Figure 3).

Phosphorylation-Dependent Isomerization of Atr by Pin1

Pin1 has a high degree of phosphate specificity (Zhou et al., 1999; Lu, 2000; Liou et al., 2011). Due to the numerous amounts of phosphorylated substrates that Pin recognizes in the cell, Pin1 can be a potential target in treatment of many diseases (Ryo et al., 2003; Kesavapany et al., 2007; Finn and Lu, 2008; Liou et al., 2011; Lu and Hunter, 2014; Lin et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015, 2016; Campaner et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018). Since Pin1’s activity on ATR requires the phosphorylation at Ser428 of ATR, this could serve as an important regulatory tool to influence the levels of the ATR isomer. Thus, phosphorylation at Ser428 may play a critical role in regulating ATR prolyl isomerization and, thus, ATR’s anti-apoptotic activity at mitochondria.

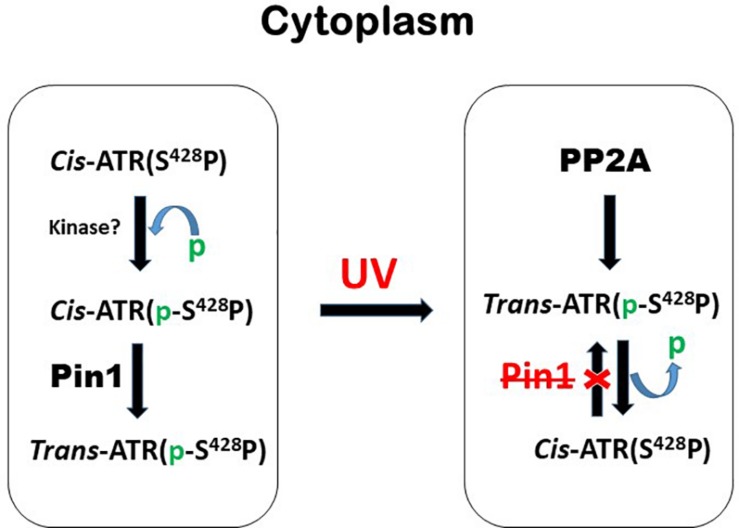

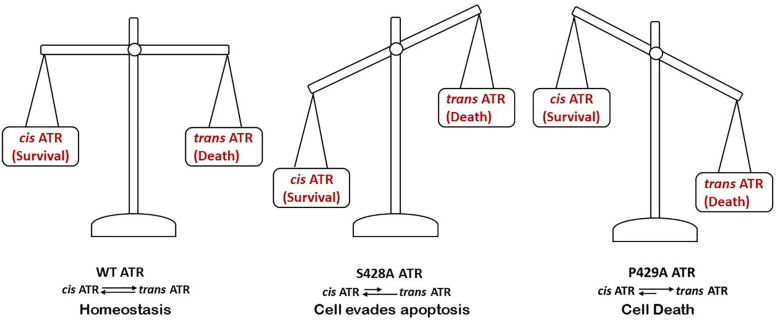

Hilton et al. (2015) showed that when the serine 428 residue in human ATR is mutated to alanine (S428A), Pin1 is unable to recognize its motif to isomerize cis-ATR to trans-ATR; hence, cytoplasmic S428A ATR exists primarily as the anti-apoptotic cis isomer. In addition, when the proline 429 residue was mutated to alanine, the P429A ATR in the cytoplasm was in the trans form. This indicates that the type of ATR present in the cytoplasm can be regulated by targeting this phosphorylation-dependent Pin1-mediated isomerization of ATR (Figure 4). An accumulation of cis-ATR at mitochondria confers a survival signal that allows the cell to escape apoptosis even following DNA damage. The evasion of cell death may allow mutations that have occurred in these cells to be passed to daughter cells. Survival of an increasing number of cells with accumulating mutations over time can increase genomic instability and cause carcinogenesis. The alternative scenario where trans-ATR is dominant in the cytoplasm leads to an increase in free t-Bid since trans ATR is unable to bind and sequester t-Bid, allowing the programmed cell death that occurs when the cell is unable to repair DNA damage. In support of this mechanism proposed by Hilton et al. (2015), Lee et al. (2015) observed that a low expression of cytoplasmic pATR (S428; which implies higher levels of cytoplasmic cis-ATR) is associated with an advanced stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) with poor disease prognosis and treatment outcomes. In contrast, no such correlations were found with nuclear pATR (S428) levels, implicating that cytoplasmic cis-ATR levels are uniquely important in the disease progression of EOC.

FIGURE 4.

A brief summary of the mechanism by which the levels of cytoplasmic cis- and trans-ATR isoforms are mediated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation before and after UV irradiation. The red X stands for inhibition or inactivation of Pin1.

The level at Ser428 phosphorylation in ATR can be determined by two important classes of proteins: protein kinases and phosphatases. The former phosphorylates Ser428 while the latter dephosphorylates this residue. The balance between the two opposing activities is critical to controlling the cis/trans balance of ATR isomers and, thus, the health of the cells. Identification of the phosphatases which have activities at Ser428 is particularly important to cancer treatment as dephosphorylation of this residue leads to an increase of anti-apoptotic cis-ATR formation (Hilton et al., 2015) and poor prognosis for cancer treatment (Lee et al., 2015). Thus, the responsible phosphatase(s) would be a reasonable target for inhibition to improve cancer treatment. Indeed, we recently identified PP2A (Protein Phosphatase 2A) as the protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates Ser428 in the Pin1 recognition motif of cytoplasmic ATR. When PP2A dephosphorylates this Ser428 residue, Pin1 can no longer recognize its motif to isomerize cytoplasmic ATR from the cis to the trans isoform (Figure 4). This key regulation was found to increase the level of cis-ATR in the cytoplasm and its accumulation at the mitochondria to bind tBid for its anti-apoptotic role (Figure 3). In addition, cells in which PP2A was inhibited were found to be significantly more sensitive to DNA damage agents. In contrast, a kinase that phosphorylates cytoplasmic ATR at Ser428 in the Pin1 recognition motif will cause an opposite effect; in the cytoplasm, there would be a relative abundance of phosphorylated substrate for Pin1 to perform its phosphorylation-dependent isomerization of cis-ATR to the trans form. Since the trans form has no direct anti-apoptotic benefit following DNA damage, the cells with a predominance of cytoplasmic trans-ATR will succumb more quickly to apoptosis. It is worth noting that UV irradiation reduces the Ser428 phosphorylation level of ATR in the cytoplasm (Hilton et al., 2015) while at the same time increasing the phosphorylation level at the same S428 residue of ATR in the nucleus of cells. The former consistently leads to accumulation of cis-ATR at mitochondria. The latter’s effect remains unknown as the nuclear phosphorylation of ATR-Ser428 has no effect on ATR checkpoint activation of Chk1 after UV damage (Liu et al., 2011). In addition, while the mechanism of ATR isomerization is defined with the cells treated with UV, Hilton et al. (2015) also show that other types of DNA damage agents such as hydroxyurea and camptothecin can induce formation of cis-ATR in the cytoplasm though less efficiently. This suggests that the mechanism defined by Hilton et al. (2015) may represent a universal pathway of ATR isomerization in response to DNA damage. By simply regulating a PTM event in the cytoplasmic ATR protein, i.e., addition or removal of a phosphate group in the Pin1 motif of ATR, one would be able to control how cells respond to a DNA damaging event: survival or death as summarized in Figures 3, 4.

Cis-Atr’s Anti-Apoptotic Function May Support an Oncogenic Process in Dividing Cells

Cancer is characterized with deregulated cell growth, where there is an imbalance in the inherent cell cycle regulation to check the rate and integrity of cell division and growth. In addition, given that cis-ATR is antiapoptotic, we hypothesize that cis-ATR may perform an oncogenic role, while Pin1 might be tumor suppressive in terms of ATR’s anti-apoptotic activity at the mitochondria. If cis-ATR is the dominant cytoplasmic form, it may block mitochondrial apoptosis and allow damaged cells to survive and mutate, even when DNA damage repair is insufficient and the abnormal cells are supposed to die via apoptosis. This evasion of apoptosis is an important hallmark of cancer cells that, over time, allows them to accumulate the mutations that define genome instability and, eventually, leads to carcinogenesis. However, if Pin1’s action is increased and trans-ATR is the dominant form of ATR in the cytoplasm, before mutations can be propagated, programmed death will occur in those cells that are too severely damaged for proper DNA repair. Thus, reduction of cytosolic cis-ATR discourages accumulation of cells with DNA damage that could be passed on to daughter cells and would promote carcinogenesis.

This hypothesis is interesting in and of itself, but is inconsistent with the existing literature which suggests other roles of Pin1 in cancer development (Figure 2). The current understanding stems primarily from observations that Pin1 is overexpressed/has increased activity in most cancers and cancer stem cells, with corresponding negative prognostic outcomes (Ayala et al., 2003; He et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2010; Girardini et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2014; Rustighi et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Nakatsu et al., 2019). Also, Pin1 upregulates many oncogenes, while downregulating several tumor suppressor genes (Chen et al., 2018). Pin1 overexpression or its over activation can be inhibited by genetic approaches or chemically with juglone (Hennig et al., 1998), all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA; Toledo et al., 2011) or KPT-6566 (Campaner et al., 2017) and, when tested, Pin1 inhibitors were able to suppress cancers (Estey et al., 1997; Budd et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2004; Lu and Hunter, 2014; Wei et al., 2015; Zhou and Lu, 2016; Lian et al., 2018). However, there are many challenges to chemically inhibiting Pin1, especially with retinoids (e.g., ATRA), the most commonly used clinical inhibitor. These include low drug bioavailability, clinical relapse and retinoid resistance, etc. (Muindi et al., 1992; Decensi et al., 2009; Arrieta et al., 2010; Moore and Potter, 2013; Jain et al., 2014). In contrast, bioinformatic analyses of human tumors (Kaplan–Meier Plots) reported in the Human Protein Atlas (7,932 cases) found that low Pin1 RNA expression is largely associated with a lower survival profile for most types (12 types) of cancer patients while high expression correlates with a higher survival profile for three types of cancer (Table 1). For two other types of cancer the relationship of survival profile with Pin1 expression is non-determined. Interestingly, two types of male-only cancer, prostate and testis, are among the three types of minorities; these patients had a higher survival profile with low versus high Pin1 RNA expression. These results also are consistent with the 5-year survival probabilities (Table 1). However, of all the 17 cancer types analyzed, only in two types, renal and pancreatic, are Pin1 expression prognostic: high Pin1 expression is favorable for better prognosis as determined by Human Protein Atlas (Table 1). This appears to contradict a recent report on the prognostic value of Pin1 in cancer which analyzed the data from 20 published papers (2,474 patients) which concluded that Pin1 overexpression was significantly associated with advanced clinical stage of cancer, lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis, although no correlation with poor differentiation was found (Khoei et al., 2019). Interestingly, it is known that over 50% of cancers have mutations in p53, and Pin1 expression was found to promote mutant p53-induced oncogenesis (Girardini et al., 2011). Also, importantly, Pin1 isomerizes wild-type p53 in DDR and the wild type p53 functions are regulated by Pin1 (Wulf et al., 2002; Zacchi et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2002). Thus, p53 status may affect the relationship between Pin1 expression and cancer as Pin1 appears to have different effects on cancer cells with mutant and wild-type p53 (Mantovani et al., 2015). It remains unknown if or how the p53 status would affect cancer prognosis in correlation with Pin1 expression levels, which is of great interest to determine. We propose that a wider role for Pin1 and its regulator partners in carcinogenesis needs to be considered and investigated further to provide better context (Han et al., 2017).

TABLE 1.

Pin1 RNA expression in caner patients analyzed by Kaplan-Meier Plot (Human Protein Atlas).

| Cancer type | Male/female (n/n) | Max post- diagnosis years | Pin1 expression | ||||||

| Survival probability | 5-year survival (%) | ||||||||

| Expression | Prognosis | ||||||||

| Low | High | Level | status | ||||||

| Lower | Higher | expression | expression | cut-off | P score | (Prognosability) | |||

| Renal | 591/286 | 16 | Low | High | 64% | 82% | 9.65 | 0.000078 | Yes |

| Pancreatic | 96/80 | 7 | Low | High | 7% | 48% | 8.72 | 0.00032 | Yes |

| Glioma | 99/54 | 7 | Low | High | 5% (∗) | 12% (∗) | 15.74 | 0.022 | No |

| Thyroid | 135/366 | 15 | Low | High | 91% | 100% | 9.19 | 0.031 | No |

| Lung | 596/398 | 20 | Low | High | 40% | 47% | 6.16 | 0.029 | No |

| Stomach | 229/125 | 10 | Low | High | 26% | 50% | 8.03 | 0.022 | No |

| Breast | 12/1063 | 23 | Low | High | 81% | 82% | 7.16 | 0.25 | No |

| Cervical | 0/291 | 17 | Low | High | 59% | 74% | 10.81 | 0.0061 | No |

| Endometrial | 0/541 | 19 | Low | High | 70% | 80% | 8.61 | 0.044 | No |

| Ovarian | 0/373 | 15 | Low | High | 27% | 38% | 13.22 | 0.0072 | No |

| Urothelial | 299/107 | 14 | Low | High | 33% | 43% | 7.49 | 0.012 | No |

| Head and Neck | 366/133 | 17 | Low | High | 39% | 57% | 8.75 | 0.0065 | No |

| Melanoma | 60/42 | 5 | High | Low | 37% (∗) | 0 (∗) | 15.17 | 0.27 | No |

| Prostate | 494/0 | 14 | High | Low | 100% | 97% | 11.77 | 0.094 | No |

| Testis | 134/0 | 20 | High | Low | 100% | 97% | 8.63 | 0.26 | No |

| Liver | 246/119 | 10 | Non-determined | 53% | 46% | 5.4 | 0.190 | No | |

| Colorectal | 322/275 | 12 | Non-determined | 63% | 60% | 8.76 | 0.065 | No | |

| Total Cases | 3679/4253 | Low:High=3:12 | (∗): 3-year Survival | ||||||

While it is logical to target Pin1 or the many processes that Pin1 regulates directly or indirectly via its substrates involved in carcinogenesis (see Figure 2), we propose that it would be significantly more effective to target the control of apoptosis, a common pathway always deregulated in carcinogenesis with uncontrolled proliferation. This is because apoptosis is the ultimate terminator and always has the final say in determining the fate, death or survival, of cells. This would tie in with the emerging idea of oncogene addiction, where the so-called “Achilles heel” of a cancer is used to deal a deathblow to that cancer (Weinstein, 2002; Weinstein and Joe, 2006, 2008). Oncogene addiction is one of the themes that has evolved in the study of tumor progression. There are innumerable causes of cancer, hence the difficulties in identifying suitable treatment targets for developing effective therapies. Research has shown that oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are constantly undergoing mutations in the background of genetic instability that can drive tumor progression. Oncogene addiction attempts to simplify the essence of carcinogenesis to a single, most important oncogenic protein that a tumor depends on for its survival, while the counterpart normal protein has little or no negative effects on normal cell survival. If this oncogenic pathway is targeted and switched off, cancer cells that are addicted to this pathway will be disproportionately affected, sparing normal cells (Weinstein, 2002; Weinstein and Joe, 2006, 2008). This is the ideal cancer treatment, with a surgical precision in its action, leaving negligible side effects that biomedical researchers have been working toward for decades.

Potential Targeting of Atr Isomerization in Cancer Therapies

Prior to the elucidation of this anti-apoptotic role of cis-ATR in the cytoplasm, a wealth of knowledge already existed about the nuclear kinase roles of ATR which is a trans isomer and several cancer therapies have taken advantage of this by targeting the kinase function of ATR to promote cancer cell killing. ATR inhibitors, in combination with chemo- and radio-therapy, have been utilized in a synthetic lethality approach to sensitize cancer cells for cell death with varied results (Wagner and Kaufmann, 2010; Toledo et al., 2011; Fokas et al., 2014; Karnitz and Zou, 2015; Lecona and Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018). Challenges to this approach include: development of specific ATR inhibitors, delivery of the ATR inhibitors to achieve useful physiological concentrations in test subjects, and specificity in killing only cancer cells and not normal cells. VX-970, AZD6738, and other ATR inhibitors are in ongoing clinical trials, being used in conjunction with chemo- or radio-therapy for breast (Kim et al., 2017), ovarian (Huntoon et al., 2013), pancreatic (Prevo et al., 2012), and small cell lung cancers (Vendetti et al., 2015). Pin1 inhibitors also are being evaluated for their usefulness in cancer therapies (Zannini et al., 2019); however, it is possible that side effects could be a concern for this targeting due to the number and diversity of important Pin1 substrates in the cell.

It should be pointed out that the current ATR inhibitors used in cancer clinical trials are specific inhibitors of ATR kinase activity which is pivotal to the hallmark ATR’s DNA damage checkpoint functions in the nucleus. Since the new anti-apoptotic activity of cis-ATR at mitochondria is independent of ATR kinase activity (Hilton et al., 2015), these inhibitors have no effect on cis-ATR’s anti-apoptotic activity. Cis-ATR (ATR-H), potentially, can be such a target protein that is novel and could be effective in cancer treatment. Cis-ATR is not directly mutagenic, but it allows cancer cells to evade apoptosis, a very important hallmark of carcinogenesis. It is possible that cancerous cells, especially with chemo- or radio-therapeutic challenge, have a proportionally higher level of cytoplasmic cis-ATR and are resistant to killing due to a low level of Pin1 or a lower level of the phosphorylation of Ser428 in ATR than normal cells (Ibarra et al., 2017). In support, a reduced level of pSer428 ATR in the cytoplasm of advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer cells correlates with a poor prognosis (Lee et al., 2015). Therefore, targeting cis-ATR as an adjuvant in treating cancers by irradiation or chemotherapy should preferentially kill cis-ATR-addicted cancer cells, with minimal effects on the normal functions of nuclear trans-ATR in cells. ATR is an essential protein (Brown and Baltimore, 2000) and its cis and trans isomers function normally and exist in a delicate balance to ensure cellular survival and normality (Figure 5). By utilizing the natural balance that exists in normal human cells between cis- and trans-ATR isoforms, we propose cis-ATR as a novel, potential target in cancer treatment. Also, cis-ATR might serve as a diagnostic marker of prognosis and treatment efficacy in cancer management.

FIGURE 5.

An appropriate balance between cytoplasmic levels of cis- and trans- ATR is critical for the wellbeing of cells.

Given the critical role of Pin1 in maintaining the balance between cis- and trans-ATR in the cytoplasm, manipulation of Pin1 subcellular level or activity could be another means to control cis-ATR formation for cancer therapeutics. Ibarra et al. recently reported different subcellular distribution of Pin1 in different cell types in zebrafish in vivo, suggesting specific mechanisms for regulating Pin1 subcellular activity are cell-type dependent (Ibarra et al., 2017). These authors also found dramatic reduction of Pin1 in the nucleus and high cytoplasmic Pin1 levels in some cell types in vivo (Ibarra et al., 2017). These findings could have important implications in terms of cytoplasmic cis-ATR formation.

Prospective

There are still important questions remaining to be answered to validate the hypotheses put forward in this review, including a better understanding of (1) how the Ser428 residue is phosphorylated or dephosphorylated under different physiological and biological conditions. Phosphorylation status plays a critical role in the regulation of ATR isomerization and, thus, its antiapoptotic activities; (2) the structural differences between the cis and trans isomers; and (3) their specific folding for substrate recognition and binding. Are there specific binding partners of cis- and trans-ATR in the cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively, which help to energetically stabilize ATR in their isoforms? If so, what are these proteins and how are they regulated. Understanding the mechanisms of each isomer’s formation and stabilization can help to define whether cis-ATR fulfils the criteria to be termed an oncoprotein. It also should be possible to develop drugs that can selectively increase or reduce the specific ATR isoform that is needed in the management of a disease, as elucidated earlier for cancer, for example.

The quest for an ideal cancer therapy began when cancer itself was described as a disease and many promising targets have been investigated in the past with varying results. Since a cancer cell starts as a normal cell that has become deregulated, the ability to selectively target only cancer cells by identification of proteins/processes unique to cancer cells remains elusive for many cancer types and stages. Such targeting should minimize adverse effects while obtaining an effective treatment. As a further complication, the pathways that lead to cancer are numerous and varied, with confounders like immunoediting, persistence of cancer stem cells, etc. Here we propose a target common to all cells: isomerization-mediated apoptosis, but in such a specifically targeted way that normal cells are spared. The isomerization of ATR by Pin1 is an important biological process that should be studied further since the existing evidence points to exciting possibilities for drug/genetic regulation of this singular process. There would be significant potential translational implications in disease diagnosis and treatment.

Finally, the ability to induce or prevent apoptosis in select groups of cells can be of importance in other diseases such as ischemia and inflammation where cell death is the major issue. Moreover, it is worth investigating if cis-ATR plays a role in elongating the life of a cell in the context of aging since more cells would be able to successfully evade apoptosis by increasing the mitochondrial health of the cell.

Author Contributions

YM wrote the draft of the manuscript based on the outlines made by YZ. YZ oversaw the process. All authors read and participated in revising the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors for their patience.

Footnotes

Funding. Part of the work described in this article was supported by NIH grants R01CA86927, R15GM112168, and R01CA219342 (to YZ).

References

- Antonelli R., De Filippo R., Middei S., Stancheva S., Pastore B., Ammassari-Teule M., et al. (2016). Pin1 modulates the synaptic content of NMDA receptors via prolyl-isomerization of PSD-95. J. Neurosci. 36 5437–5447. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3124-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta O., Gonzalez-De la Rosa C. H., Arechaga-Ocampo E., Villanueva-Rodriguez G., Ceron-Lizarraga T. L., Martinez-Barrera L., et al. (2010). Randomized phase II trial of All-trans-retinoic acid with chemotherapy based on paclitaxel and cisplatin as first-line treatment in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 28 3463–3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala G., Wang D., Wulf G., Frolov A., Li R., Sowadski J., et al. (2003). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 is a novel prognostic marker in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 63 6244–6251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazin K. N., Mallis R. J., Fulton D. B., Andreotti A. H. (2002). Regulation of the tyrosine kinase Itk by the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 1899–1904. 10.1073/pnas.042529199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E. J., Baltimore D. (2000). ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 14 397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd G. T., Adamson P. C., Gupta M., Homayoun P., Sandstrom S. K., Murphy R. F., et al. (1998). Phase I/II trial of all-trans retinoic acid and tamoxifen in patients with advanced breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 4 635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows A. E., Elledge S. J. (2008). How ATR turns on: TopBP1 goes on ATRIP with ATR. Genes Dev. 22 1416–1421. 10.1101/gad.1685108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaner E., Rustighi A., Zannini A., Cristiani A., Piazza S., Ciani Y., et al. (2017). A covalent PIN1 inhibitor selectively targets cancer cells by a dual mechanism of action. Nat. Commun. 8:15772. 10.1038/ncomms15772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Chang C. C., Lee T. H., Luo M., Huang P., Liao P. H., et al. (2013). SENP1 deSUMOylates and regulates Pin1 protein activity and cellular function. Cancer Res. 73 3951–3962. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Li W., Sultana R., You M. H., Kondo A., Shahpasand K., et al. (2015). Pin1 cysteine-113 oxidation inhibits its catalytic activity and cellular function in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 76 13–23. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Wu Y. R., Yang H. Y., Li X. Z., Jie M. M., Hu C. J., et al. (2018). Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 9:883. 10.1038/s41419-018-0844-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia A., Elledge S. J. (2010). The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 40 179–204. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimprich K. A., Cortez D. (2008). ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9 616–627. 10.1038/nrm2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez D., Guntuku S., Qin J., Elledge S. J. (2001). ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science 294 1713–1716. 10.1126/science.1065521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craveur P., Joseph A. P., Poulain P., de Brevern A. G., Rebehmed J. (2013). Cis-trans isomerization of omega dihedrals in proteins. Amino Acids 45 279–289. 10.1007/s00726-013-1511-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decensi A., Robertson C., Guerrieri-Gonzaga A., Serrano D., Cazzaniga M., Mora S., et al. (2009). Randomized double-blind 2 x 2 trial of low-dose tamoxifen and fenretinide for breast cancer prevention in high-risk premenopausal women. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 3749–3756. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin C. M., Berman A. J., Miranker A. D. (2006). A native to amyloidogenic transition regulated by a backbone trigger. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13 202–208. 10.1038/nsmb1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerdt F., Yuan J., Saxena K., Martin B., Kappel S., Lindenau C., et al. (2005). Polo-like kinase 1-mediated phosphorylation stabilizes Pin1 by inhibiting its ubiquitination in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280 36575–36583. 10.1074/jbc.m504548200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Boustani M., De Stefano L., Caligiuri I., Mouawad N., Granchi C., Canzonieri V., et al. (2018). A guide to PIN1 function and mutations across cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1477. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey E., Thall P. F., Pierce S., Kantarjian H., Keating M. (1997). Treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia without cytarabine. J. Clin. Oncol. 15 483–490. 10.1200/jco.1997.15.2.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn G., Lu K. P. (2008). Phosphorylation-specific prolyl isomerase Pin1 as a new diagnostic and therapeutic target for cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 8 223–229. 10.2174/156800908784293622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G., Schmid F. X. (1990). The mechanism of protein folding. Implications of in vitro refolding models for de novo protein folding and translocation in the cell. Biochemistry 29 2205–2212. 10.1021/bi00461a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn R. L., Zou L. (2011). ATR: a master conductor of cellular responses to DNA replication stress. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36 133–140. 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokas E., Prevo R., Hammond E. M., Brunner T. B., McKenna W. G., Muschel R. J. (2014). Targeting ATR in DNA damage response and cancer therapeutics. Cancer Treat. Rev. 40 109–117. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis A. V., Llambi F., Merritt P., Chipuk J. E., Green D. R., Kriwacki R. W. (2015). Pin1-induced proline isomerization in cytosolic p53 mediates BAX activation and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 59 677–684. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardini J. E., Napoli M., Piazza S., Rustighi A., Marotta C., Radaelli E., et al. (2011). A Pin1/mutant p53 axis promotes aggressiveness in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 20 79–91. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothel S. F., Marahiel M. A. (1999). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55 423–436. 10.1007/s000180050299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grison A., Mantovani F., Comel A., Agostoni E., Gustincich S., Persichetti F., et al. (2011). Ser46 phosphorylation and prolyl-isomerase Pin1-mediated isomerization of p53 are key events in p53-dependent apoptosis induced by mutant huntingtin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 17979–17984. 10.1073/pnas.1106198108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. J., Choi B. Y., Surh Y. J. (2017). Dual roles of Pin1 in cancer development and progression. Curr. Pharm Des. 23 4422–4425. 10.2174/1381612823666170703164711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Zhou F., Shao K., Hang J., Wang H., Rayburn E., et al. (2007). Overexpression of Pin1 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and its correlation with lymph node metastases. Lung Cancer 56 51–58. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig L., Christner C., Kipping M., Schelbert B., Rucknagel K. P., Grabley S., et al. (1998). Selective inactivation of parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases by juglone. Biochemistry 37 5953–5960. 10.1021/bi973162p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton B. A., Li Z., Musich P. R., Wang H., Cartwright B. M., Serrano M., et al. (2015). ATR plays a direct antiapoptotic role at mitochondria, which is regulated by prolyl isomerase Pin1. Mol. Cell. 60 35–46. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderaker M. P., Raines R. T. (2003). An electronic effect on protein structure. Protein Sci. 12 1188–1194. 10.1110/ps.0241903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T., McRackan D., Vincent T. S., Gert de Couet H. (2001). Drosophila Pin1 prolyl isomerase Dodo is a MAP kinase signal responder during oogenesis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3 538–543. 10.1038/35078508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntoon C. J., Flatten K. S., Wahner Hendrickson A. E., Huehls A. M., Sutor S. L., Kaufmann S. H., et al. (2013). ATR inhibition broadly sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to chemotherapy independent of BRCA status. Cancer Res. 73 3683–3691. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra M. S., Borini Etichetti C., Di Benedetto C., Rosano G. L., Margarit E., Del Sal G., et al. (2017). Dynamic regulation of Pin1 expression and function during zebrafish development. PLoS One 12:e0175939. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P., Kantarjian H., Estey E., Pierce S., Cortes J., Lopez-Berestein G., et al. (2014). Single-agent liposomal all-trans-retinoic Acid as initial therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia: 13-year follow-up data. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 14 e47–e49. 10.1016/j.clml.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnitz L. M., Zou L. (2015). Molecular pathways: targeting ATR in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 4780–4785. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavapany S., Patel V., Zheng Y. L., Pareek T. K., Bjelogrlic M., Albers W., et al. (2007). Inhibition of Pin1 reduces glutamate-induced perikaryal accumulation of phosphorylated neurofilament-H in neurons. Mol. Biol. Cell. 18 3645–3655. 10.1091/mbc.e07-03-0237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoei S. G., Mohammadi C., Mohammadi Y., Sameri S., Najafi R. (2019). Prognostic value of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase 1 (PIN1) in human malignant tumors. Clin. Transl. Oncol. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Min A., Im S. A., Jang H., Lee K. H., Lau A., et al. (2017). Anti-tumor activity of the ATR inhibitor AZD6738 in HER2 positive breast cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 140 109–119. 10.1002/ijc.30373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecona E., Fernandez-Capetillo O. (2018). Targeting ATR in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18 586–595. 10.1038/s41568-018-0034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B., Lee H. J., Cho H. Y., Suh D. H., Kim K., No J. H., et al. (2015). Ataxia-telangiectasia and RAD3-related and ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated proteins in epithelial ovarian carcinoma: their expression and clinical significance. Anticancer Res. 35 3909–3916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. H., Chen C. H., Suizu F., Huang P., Schiene-Fischer C., Daum S., et al. (2011). Death-associated protein kinase 1 phosphorylates Pin1 and inhibits its prolyl isomerase activity and cellular function. Mol. Cell. 42 147–159. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X., Lin Y. M., Kozono S., Herbert M. K., Li X., Yuan X., et al. (2018). Pin1 inhibition exerts potent activity against acute myeloid leukemia through blocking multiple cancer-driving pathways. J. Hematol. Oncol. 11:73. 10.1186/s13045-018-0611-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Li H. Y., Lee Y. C., Calkins M. J., Lee K. H., Yang C. N., et al. (2015). Landscape of Pin1 in the cell cycle. Exp. Biol. Med. 240 403–408. 10.1177/1535370215570829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou Y. C., Zhou X. Z., Lu K. P. (2011). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 as a molecular switch to determine the fate of phosphoproteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36 501–514. 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Shiotani B., Lahiri M., Marechal A., Tse A., Leung C. C., et al. (2011). ATR autophosphorylation as a molecular switch for checkpoint activation. Mol. Cell. 43 192–202. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. P. (2000). Phosphorylation-dependent prolyl isomerization: a novel cell cycle regulatory mechanism. Prog. Cell. Cycle Res. 4 83–96. 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. P., Finn G., Lee T. H., Nicholson L. K. (2007). Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 619–629. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. P., Hanes S. D., Hunter T. (1996). A human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase essential for regulation of mitosis. Nature 380 544–547. 10.1038/380544a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. P., Zhou X. Z. (2007). The prolyl isomerase PIN1: a pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8 904–916. 10.1038/nrm2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Hunter T. (2014). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 in cancer. Cell Res. 24 1033–1049. 10.1038/cr.2014.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M. L., Gong C., Chen C. H., Lee D. Y., Hu H., Huang P., et al. (2014). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 acts downstream of miR200c to promote cancer stem-like cell traits in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74 3603–3616. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Rodriguez A., Sugimoto K. (2019). Activation of ATR-related protein kinase upon DNA damage recognition. Curr. Genet. 66 327–333. 10.1007/s00294-019-01039-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani F., Zannini A., Rustighi A., Del Sal G. (2015). Interaction of p53 with prolyl isomerases: healthy and unhealthy relationships. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1850 2048–2060. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S., Ballif B. A., Smogorzewska A., McDonald E. R., III, Hurov K. E., Luo J., et al. (2007). ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 316 1160–1166. 10.1126/science.1140321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. D., Potter A. (2013). Pin1 inhibitors: pitfalls, progress and cellular pharmacology. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23 4283–4291. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordes D. A., Cortez D. (2008). Activation of ATR and related PIKKs. Cell Cycle 7 2809–2812. 10.4161/cc.7.18.6689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordes D. A., Glick G. G., Zhao R., Cortez D. (2008). TopBP1 activates ATR through ATRIP and a PIKK regulatory domain. Genes Dev. 22 1478–1489. 10.1101/gad.1666208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muindi J., Frankel S. R., Miller W. H., Jr., Jakubowski A., Scheinberg D. A., Young C. W., et al. (1992). Continuous treatment with all-trans retinoic acid causes a progressive reduction in plasma drug concentrations: implications for relapse and retinoid “resistance” in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 79 299–303. 10.1182/blood.v79.2.299.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Greenwood A., Binder L., Bigio E. H., Denial S., Nicholson L., et al. (2012). Proline isomer-specific antibodies reveal the early pathogenic tau conformation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 149 232–244. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Zhen Zhou X., Ping Lu K. (2013). Cis phosphorylated tau as the earliest detectable pathogenic conformation in Alzheimer disease, offering novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Prion 7 117–120. 10.4161/pri.22849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu Y., Yamamotoya T., Ueda K., Ono H., Inoue M. K., Matsunaga Y., et al. (2019). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 in metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 470 106–114. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam E. A., Cortez D. (2011). ATR signalling: more than meeting at the fork. Biochem. J. 436 527–536. 10.1042/BJ20102162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino L., Sun A., Lu P. J., Zhou X. Z., Balastik M., Finn G., et al. (2006). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates amyloid precursor protein processing and amyloid-beta production. Nature 440 528–534. 10.1038/nature04543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton P., Rimessi A., Marchi S., Orsini F., Migliaccio E., Giorgio M., et al. (2007). Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315 659–663. 10.1126/science.1135380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevo R., Fokas E., Reaper P. M., Charlton P. A., Pollard J. R., McKenna W. G., et al. (2012). The novel ATR inhibitor VE-821 increases sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13 1072–1081. 10.4161/cbt.21093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippmann J. F., Hobbie S., Daiber C., Guilliard B., Bauer M., Birk J., et al. (2000). Phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization catalyzed by Pin1 is essential for tumor cell survival and entry into mitosis. Cell Growth Differ. 11 409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustighi A., Zannini A., Tiberi L., Sommaggio R., Piazza S., Sorrentino G., et al. (2014). Prolyl-isomerase Pin1 controls normal and cancer stem cells of the breast. EMBO Mol. Med. 6 99–119. 10.1002/emmm.201302909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryo A., Liou Y. C., Lu K. P., Wulf G. (2003). Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a catalyst for oncogenesis and a potential therapeutic target in cancer. J. Cell. Sci. 116 773–783. 10.1242/jcs.00276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldivar J. C., Cortez D., Cimprich K. A. (2017). Publisher correction: the essential kinase ATR: ensuring faithful duplication of a challenging genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:783. 10.1038/nrm.2017.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Unsal-Kacmaz K., Linn S. (2004). Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73 39–85. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar P., Reichman C., Saleh T., Birge R. B., Kalodimos C. G. (2007). Proline cis-trans isomerization controls autoinhibition of a signaling protein. Mol. Cell. 25 413–426. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidpeter P. A., Schmid F. X. (2015). Prolyl isomerization and its catalysis in protein folding and protein function. J. Mol. Biol. 427 1609–1631. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z. X., Shi Z. Z., Fang J., Gu B. W., Li J. M., Zhu Y. M., et al. (2004). All-trans retinoic acid/As2O3 combination yields a high quality remission and survival in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 5328–5335. 10.1073/pnas.0400053101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Burrage K., Yuan Z., Huber T. (2006). Prediction of cis/trans isomerization in proteins using PSI-BLAST profiles and secondary structure information. BMC Bioinformatics 7:124. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino G., Comel A., Mantovani F., Del Sal G. (2014). Regulation of mitochondrial apoptosis by Pin1 in cancer and neurodegeneration. Mitochondrion 19(Pt A), 88–96. 10.1016/j.mito.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M., Murina O., Huhn D., Ferretti L. P., Walser R., Hanggi K., et al. (2013). Prolyl isomerase PIN1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair by counteracting DNA end resection. Mol. Cell. 50 333–343. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D. E., Sarkar A., Wampler J. E. (1990). Occurrence and role of cis peptide bonds in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 214 253–260. 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90159-j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Zhou F., Wan J., Hang J., Chen Z., Li B., et al. (2010). Pin1 expression contributes to lung cancer: prognosis and carcinogenesis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 9 111–119. 10.4161/cbt.9.2.10341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C. (1968). Protein denaturation. Adv. Protein Chem. 23 121–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toko H., Hariharan N., Konstandin M. H., Ormachea L., McGregor M., Gude N. A., et al. (2014). Differential regulation of cellular senescence and differentiation by prolyl isomerase Pin1 in cardiac progenitor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289 5348–5356. 10.1074/jbc.M113.526442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toko H., Konstandin M. H., Doroudgar S., Ormachea L., Joyo E., Joyo A. Y., et al. (2013). Regulation of cardiac hypertrophic signaling by prolyl isomerase Pin1. Circ. Res. 112 1244–1252. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo L. I., Murga M., Fernandez-Capetillo O. (2011). Targeting ATR and Chk1 kinases for cancer treatment: a new model for new (and old) drugs. Mol. Oncol. 5 368–373. 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendetti F. P., Lau A., Schamus S., Conrads T. P., O’Connor M. J., Bakkenist C. J. (2015). The orally active and bioavailable ATR kinase inhibitor AZD6738 potentiates the anti-tumor effects of cisplatin to resolve ATM-deficient non-small cell lung cancer in vivo. Oncotarget 6 44289–44305. 10.18632/oncotarget.6247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J. M., Kaufmann S. H. (2010). Prospects for the use of ATR inhibitors to treat cancer. Pharmaceuticals 3 1311–1334. 10.3390/ph3051311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S., Kozono S., Kats L., Nechama M., Li W., Guarnerio J., et al. (2015). Active Pin1 is a key target of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia and breast cancer. Nat. Med. 21 457–466. 10.1038/nm.3839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S., Yoshida N., Finn G., Kozono S., Nechama M., Kyttaris V. C., et al. (2016). Pin1-targeted therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 2503–2513. 10.1002/art.39741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein I. B. (2002). Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes–the Achilles heal of cancer. Science 297 63–64. 10.1126/science.1073096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein I. B., Joe A. (2008). Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res. 68 3077–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein I. B., Joe A. K. (2006). Mechanisms of disease: oncogene addiction–a rationale for molecular targeting in cancer therapy. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 3 448–457. 10.1038/ncponc0558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulf G. M., Liou Y. C., Ryo A., Lee S. W., Lu K. P. (2002). Role of Pin1 in the regulation of p53 stability and p21 transactivation, and cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 277 47976–47979. 10.1074/jbc.c200538200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Cheung C. C., Chow C., Lun S. W., Cheung S. T., Lo K. W. (2016). Overexpression of PIN1 enhances cancer growth and aggressiveness with cyclin D1 induction in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One 11:e0156833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe M. B., Schutkowski M., Shen M., Zhou X. Z., Stukenberg P. T., Rahfeld J. U., et al. (1997). Sequence-specific and phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization: a potential mitotic regulatory mechanism. Science 278 1957–1960. 10.1126/science.278.5345.1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. C., Chuang J. Y., Jeng W. Y., Liu C. I., Wang A. H., Lu P. J., et al. (2014). Pin1-mediated Sp1 phosphorylation by CDK1 increases Sp1 stability and decreases its DNA-binding activity during mitosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 13573–13587. 10.1093/nar/gku1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E. S., Means A. R. (2007). PIN1, the cell cycle and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 381–388. 10.1038/nrc2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchi P., Gostissa M., Uchida T., Salvagno C., Avolio F., Volinia S., et al. (2002). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 reveals a mechanism to control p53 functions after genotoxic insults. Nature 419 853–857. 10.1038/nature01120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannini A., Rustighi A., Campaner E., Del Sal G. (2019). Oncogenic hijacking of the PIN1 signaling network. Front. Oncol. 9:94. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., You H., Zhou X. Z., Murray S. A., Uchida T., Wulf G., et al. (2002). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 is a regulator of p53 in genotoxic response. Nature 419 849–853. 10.1038/nature01116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Z., Kops O., Werner A., Lu P. J., Shen M., Stoller G., et al. (2000). Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization regulates dephosphorylation of Cdc25C and tau proteins. Mol. Cell. 6 873–883. 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00083-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Z., Lu K. P. (2016). The isomerase PIN1 controls numerous cancer-driving pathways and is a unique drug target. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16 463–478. 10.1038/nrc.2016.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Z., Lu P. J., Wulf G., Lu K. P. (1999). Phosphorylation-dependent prolyl isomerization: a novel signaling regulatory mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56 788–806. 10.1007/s000180050026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Elledge S. J. (2003). Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300 1542–1548. 10.1126/science.1083430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]