Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine methodological and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews and meta-analyses which compare diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) of multiple index tests, identify good practice, and develop guidance for better reporting.

Study Design and Setting

Methodological survey of 127 comparative or multiple tests reviews published in 74 different general medical and specialist journals. We summarized methods and reporting characteristics that are likely to differ between reviews of a single test and comparative reviews. We then developed guidance to enhance reporting of test comparisons in DTA reviews.

Results

Of 127 reviews, 16 (13%) reviews restricted study selection and test comparisons to comparative accuracy studies while the remaining 111 (87%) reviews included any study type. Fifty-three reviews (42%) statistically compared test accuracy with only 18 (34%) of these using recommended methods. Reporting of several items—in particular the role of the index tests, test comparison strategy, and limitations of indirect comparisons (i.e., comparisons involving any study type)—was deficient in many reviews. Five reviews with exemplary methods and reporting were identified.

Conclusion

Reporting quality of reviews which evaluate and compare multiple tests is poor. The guidance developed, complemented with the exemplars, can assist review authors in producing better quality comparative reviews.

Keywords: Comparative accuracy, Diagnostic accuracy, Test accuracy, Meta-analysis, Systematic review, Test comparison

What is new?

Key findings

-

•

Methods known to have methodological flaws are frequently used in reviews which evaluate and compare the accuracy of multiple tests. Reporting quality is variable but often poor.

-

•

Test comparisons based on studies that have not directly compared the index tests are common in reviews but review authors fail to appreciate the potential for bias due to confounding.

What this adds to what was known?

-

•

Guidance developed to promote better conduct and reporting of test comparisons in diagnostic accuracy reviews and to facilitate their appraisal. Exemplars also provided to assist review authors.

What is the implication and what should change now?

-

•

To avoid misleading conclusions and recommendations, the methodological rigor and reporting of comparative reviews should be improved.

-

•

Researchers and funders should recognize the merit of designing studies for obtaining reliable evidence about the relative accuracy of competing diagnostic tests.

1. Introduction

Medical tests are essential in guiding patient management decisions. Ideally, tests should only be recommended for routine clinical use based on evidence of their clinical performance (diagnostic accuracy) and clinical impact (benefits and harms) derived from relevant, high-quality primary studies, and systematic reviews. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) generally assess the performance of one index test at a time, thus providing a limited view of the test options available for a given condition and no information about the performance of alternatives. However, comparative reviews which compare the accuracy of two or more index tests are potentially more useful to clinicians and policy-makers for guiding decision-making about optimal test selection.

Because test evaluation is often limited to the assessment of test accuracy with limited or no regulatory requirement to demonstrate clinical impact [1], it is vital that in the rapidly expanding evidence base, comparative accuracy reviews are conducted appropriately and well reported to avoid misleading conclusions and recommendations. Several reporting checklists have been developed to improve the transparency and reproducibility of medical research, including the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [2] and PRISMA-DTA, the extension for DTA reviews [3]. Comparative accuracy reviews and meta-analyses are more challenging to perform than those of a single test; high-quality reporting will enable assessment of the credibility of analysis methods and findings. Therefore, our aim was to summarize the methodological and reporting characteristics of comparative accuracy reviews, provide examples of good practice, and develop guidance for improving the reporting of test comparisons in future DTA reviews.

2. Methods

2.1. Terminology

To avoid confusion due to lack of standard terminology for types of test accuracy studies and systematic reviews, we describe here our choice of terminology. In Appendix Box 1, we provide a summary and other relevant definitions.

Unlike randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions, which have a control arm, most test accuracy studies do not compare the index test with alternative index tests [4]. We used the term “noncomparative” to describe a primary study that evaluated a single index test or only one of the index tests being evaluated in a review, and “comparative” to describe a study that made a head-to-head comparison by comparing the accuracy of at least two index tests in the same study population. A comparative study may either randomize patients to receive only one of the index tests (randomized design), or apply all the index tests to each patient (paired or within-subject design) [4]. With both designs, patients also receive the reference standard. For brevity, we will often refer to the index test simply as test.

We defined a comparative accuracy review as a review that met at least one of the following four criteria: (1) clear objective to compare the accuracy of at least two tests; (2) selected only comparative studies; (3) performed statistical analyses comparing the accuracy of all or a pair of tests; or (4) performed a direct (head-to-head) comparison of two tests. Reviews that assessed multiple tests but did not meet any of the four criteria were termed a multiple test review. Such reviews assess each test individually without making formal comparisons between tests and often include a large number of tests such as signs and symptoms from clinical examination. We included this category of reviews to be comprehensive and to avoid excluding reviews in the absence of established terminology.

The two main approaches for test comparisons in a DTA review are direct and indirect (between-study uncontrolled) comparisons (Appendix Fig. 1). In a direct comparison, only studies that have evaluated all the index tests are included in the comparison, whereas an indirect comparison includes all eligible studies that have evaluated at least one of the index tests.

2.2. Data sources

We used an existing collection of 1,023 systematic reviews published up to October 2012. The reviews were originally identified for an earlier empirical study using a previously described search strategy [4]. The reviews were identified by searching the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for reviews with a structured abstract and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR issue 11, 2012). Reviews undergo quality appraisal before inclusion in DARE and so we expect reviews in DARE to be of higher quality than would be expected in the wider literature. We did not update the search because DARE is no longer being updated and we judged it unlikely that more recent reviews from the general literature would be of better methodological quality given the findings of recent empiric studies of DTA reviews [5,6]. Early publications (1980s and 1990s) of DTA reviews followed methodology for intervention reviews and key advances in methodology for DTA reviews were published between 1993 and 2005 [7]. For these reasons, and to make allowance for dissemination of methods, reviews for the current study were limited to a 5-year period from January 2008 to October 2012.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

All test accuracy reviews that evaluated at least two tests and included a meta-analysis were eligible. We excluded reviews where full-text papers were unavailable, had insufficient data to determine study type (comparative or noncomparative), or where different tests were analyzed together as a single test without separate meta-analysis results for each test.

2.4. Review selection and data extraction

Using a revised screening form from a previous empiric study, one assessor (Y.T. or C.P.) assessed review eligibility by screening the abstract, followed by full-text examination. When eligibility was unclear, the inclusion decision was made following discussion with a member of the author team (J.D.).

We scrutinized full-text articles and their supplementary files. Data extraction was undertaken by one assessor (Y.T.). To verify the data, a random subset of half of the included reviews was generated using the SURVEYSELECT procedure in SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data were extracted from these reviews by a second assessor. Any disagreements were discussed by the two assessors and agreement was achieved without having to involve a third person. We focused on methodological and reporting characteristics likely to differ between reviews of a single test and comparative reviews. We extracted data on general, methodological, and reporting characteristics. These included data on target condition, tests evaluated, study design, and the analytical methods used for comparing tests and investigating differences between studies.

2.5. Development of test comparison reporting guidance

To identify a set of criteria, we used the list of methodological and reporting characteristics that we devised and the PRISMA-DTA checklist, combined with theoretical reasoning based on published methodological recommendations [[7], [8], [9]] and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy [10]. The criteria were selected to emphasize their importance for test comparisons when completing the PRISMA-DTA checklist for a comparative review.

2.6. Data analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized using the median, range, and interquartile range. Using the criteria and definition specified in section 2.1, we categorized reviews into comparative and multiple tests reviews. We subdivided comparative reviews into comparative reviews with and without a statistical comparison because one of the key aspects that we examined was synthesis methods. Thus we summarized and presented our findings within three review categories. All data analyses were performed using Stata SE version 13.0 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

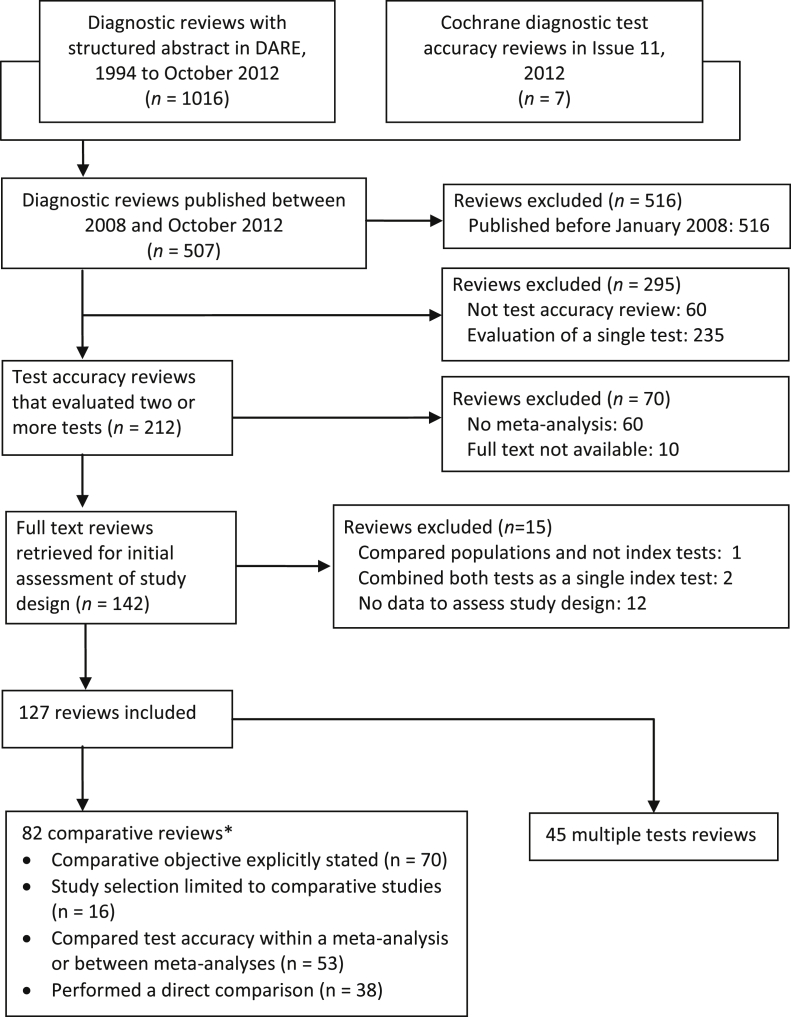

The flow of reviews through the screening and selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 1,023 reviews in the collection, 127 reviews met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

Flow of reviews through the selection process. *The 82 comparative accuracy reviews met at least one of the following four criteria: (1) clear objective to compare the accuracy of at least two tests; (2) selected only comparative studies; (3) performed statistical analyses comparing the accuracy of all or at least a pair of tests; or (4) performed a direct (head-to-head) comparison of two tests.

3.1. General characteristics

There were 82 comparative reviews and 45 multiple test reviews. Of the 82 comparative reviews, 53 (66%) formally compared test accuracy. Characteristics of the 127 reviews are summarized in Table 1. The reviews were published in 74 different journals, with the majority [93 (73%)] in specialist medical journals. The reviews covered a broad array of target conditions and test types, with neoplasms (37%), and imaging tests (43%) being the most frequently assessed target condition and test type. The median (interquartile range) number of comparative and noncomparative studies included per review were 6 (3 to 11) and 14 (3 to 24), respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of 127 reviews of comparative accuracy and multiple tests

| Characteristic | Comparative reviews |

Multiple test reviews | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical test performed to compare accuracy | ||||

| Yes | No or uncleara | |||

| Number of reviews | 53 (42) | 29 (23) | 45 (35) | 127 |

| Year of publication | ||||

| 2008 | 14 (26) | 11 (38) | 13 (29) | 38 (30) |

| 2009 | 6 (11) | 10 (34) | 8 (18) | 24 (19) |

| 2010 | 16 (30) | 4 (14) | 11 (24) | 31 (24) |

| 2011 | 13 (25) | 3 (10) | 7 (16) | 23 (18) |

| 2012b | 4 (8) | 1 (3) | 6 (13) | 11 (9) |

| Type of publication | ||||

| Cochrane review | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 5 (4) |

| General medical journal | 5 (9) | 5 (17) | 13 (29) | 23 (18) |

| Specialist medical journal | 42 (79) | 22 (76) | 30 (64) | 93 (73) |

| Technology assessment report | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Number of tests evaluated | ||||

| 2 | 20 (38) | 14 (48) | 12 (27) | 46 (36) |

| 3 | 12 (23) | 6 (21) | 4 (9) | 22 (17) |

| 4 | 8 (15) | 3 (10) | 4 (9) | 15 (12) |

| ≥5 | 13 (25) | 6 (21) | 25 (56) | 44 (35) |

| Clinical topic (according to ICD-11 Version: 2018) | ||||

| Circulatory system | 9 (17) | 5 (17) | 5 (11) | 19 (15) |

| Digestive system | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 8 (18) | 12 (9) |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 3 (6) | 4 (14) | 9 (20) | 16 (13) |

| Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 5 (4) |

| Mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 3 (7) | 6 (5) |

| Musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 4 (9) | 6 (5) |

| Neoplasms | 28 (53) | 12 (41) | 7 (16) | 47 (37) |

| Other ICD-11 codesc | 5 (9) | 4 (14) | 7 (16) | 16 (13) |

| Type of tests evaluated | ||||

| Biopsy | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Clinical and physical examination | 5 (9) | 3 (10) | 15 (33) | 23 (18) |

| Device | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Imaging | 32 (60) | 13 (45) | 9 (20) | 54 (43) |

| Laboratory | 8 (15) | 8 (28) | 12 (27) | 28 (22) |

| RDT or POCT | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (9) | 5 (4) |

| Self-administered questionnaire | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Combinations of any of the aboved | 5 (9) | 3 (10) | 5 (11) | 13 (10) |

| Clinical purpose of the tests | ||||

| Diagnostic | 42 (79) | 23 (79) | 44 (98) | 109 (86) |

| Monitoring | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Prognostic/prediction | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Response to treatment | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Screening | 3 (6) | 4 (14) | 1 (2) | 8 (6) |

| Staging | 6 (11) | 0 | 0 | 6 (5) |

| Number of test accuracy studies in reviews | ||||

| Median (range) | 25 (6–103) | 17 (5–82) | 19 (3–79) | 20 (3–103) |

| Interquartile range | 14–43 | 11–32 | 12–24 | 12–34 |

| Number of comparative studies | ||||

| Median (range) | 7 (0–59) | 6 (0–32) | 4 (0–52) | 6 (0–59) |

| Interquartile range | 4–14 | 1–11 | 2–10 | 3–11 |

| Number of noncomparative studies | ||||

| Median (range) | 17 (0–98) | 6 (0–79) | 10 (0–76) | 14 (0–98) |

| Interquartile range | 6–32 | 0–27 | 5–20 | 3–24 |

Abbreviations: ICD-11, International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision; RDT, rapid diagnostic test; POCT, point of care test.

Numbers in parentheses are column percentages unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

In 3 reviews, it was unclear whether a statistical comparison of test accuracy was done.

Includes only studies published up to October 2012.

Includes 8 ICD-11 codes that had fewer than 5 reviews across the 3 groups.

Tests evaluated in a review were not of the same type.

3.2. Statistical characteristics

3.2.1. Use of comparative studies and test comparison strategies

Sixteen (13%) reviews restricted study selection and test comparisons to comparative studies, whereas the remaining 111 (87%) reviews included any study type (Table 2). In 22 reviews (17%), both direct and indirect comparisons were performed with the direct comparisons performed as secondary analyses using pairs of tests for which data were available. Direct comparisons were not performed in 49 (39%) reviews even though comparative studies were available in 40 of the reviews and qualitative or quantitative syntheses would have been possible.

Table 2.

Strategies and methods for test comparisons

| Characteristic | Comparative reviews |

Multiple test reviews | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical analyses to compare test accuracy | ||||

| Yes | No or unclear | |||

| Number of reviewsa | 53 (42) | 29 (23) | 45 (35) | 127 (100) |

| Study type | ||||

| Comparative only | 8 (15) | 8 (28) | 0 | 16 (13) |

| Any study type | 45 (85) | 21 (72) | 45 (100) | 111 (87) |

| Test comparison strategy | ||||

| Direct comparison only | 8 (15) | 8 (28) | 0 | 16 (13) |

| Indirect comparison only—comparative studies available | 26 (49) | 10 (34) | 4 (9) | 40 (32) |

| Indirect comparison only—no comparative studies available | 2 (4) | 6 (21) | 1 (2) | 9 (7) |

| Both direct and indirect comparison | 17 (32) | 5 (17) | 0 | 22 (17) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 40 (89) | 40 (32) |

| Method used for test comparisonb | ||||

| Meta-regression—hierarchical model | 18 (34) | 0 | 0 | 18 (14) |

| Meta-regression—SROC regression | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Meta-regression—ANCOVA | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Meta-regression—logistic regression | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Univariate pooling of difference in sensitivity and specificity or DORs | 6 (11) | 0 | 0 | 6 (5) |

| Naïve (comparison of pooled estimates from separate meta-analyses) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Z-test | 15 (28) | 0 | 0 | 15 (12) |

| Paired t-test | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Unpaired t-test | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Chi-squared test | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Comparison of Q* statistic and their SEsc | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Overlapping confidence intervals | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Narrative | 0 | 9 (31) | 4 (9) | 13 (10) |

| None | 0 | 14 (48) | 40 (89) | 54 (43) |

| Unclear | 5 (9) | 3 (10) | 1 (2) | 9 (7) |

| Relative measures used to summarize differences in test accuracy | 18 (34) | 0 | 0 | 18 (14) |

| Multiple thresholds included | 13 (25) | 12 (41) | 17 (38) | 42 (33) |

| If multiple thresholds included, were they accounted for in the comparative meta-analysis (meta-analysis at each threshold or fitted appropriate model) | ||||

| Yes | 6 (46) | 0 | 0 | 6 (46) |

| No | 4 (31) | 0 | 0 | 4 (31) |

| Unclear | 3 (23) | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; SE, standard error; SROC, summary receiver operating characteristic.

Numbers in parentheses are column percentages unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Numbers in parentheses are row percentages.

These methods either involve a comparative meta-analysis or follow-on from a meta-analysis of each test individually.

Moses et al. [11] proposed the Q* statistic as an alternative to the area under the curve. Q* is the point on the SROC curve where sensitivity is equal to specificity, that is, the intersection of the summary curve and the line of symmetry.

3.2.2. Methods for comparative meta-analysis and informal comparisons

We classified methods used in the 53 comparative reviews that statistically compared test accuracy into three main groups: (1) naïve comparison (19/53, 36%) which refers to a comparison where a statistical test, for example, a Z-test, was used to compare summary estimates from separate meta-analysis of one test with summary estimates from the meta-analysis of another test; (2) univariate pooling of differences in sensitivity and specificity, or pooling of differences in the diagnostic odds ratio (6/53, 11%); and (3) meta-regression by adding test type as a covariate to a meta-analytic model (23/53, 44%). For the remaining 5 (9%) reviews, the method used was unclear. Relative measures were used to summarize differences in accuracy in 18 of the 53 (34%) reviews.

For the remaining 29 comparative reviews that did not formally compare tests (i.e., through statistical quantification of the difference in accuracy, either via a P-value or estimate of the difference), three (10%) determined the statistical significance of differences in test accuracy based on whether or not confidence intervals overlapped, nine (31%) narratively compared tests, 14 (48%) did not perform a comparison and three (10%) were unclear.

3.2.3. Investigations of heterogeneity

Investigations of heterogeneity were performed for individual tests in 67 (53%) reviews, of which 24 (36%) used meta-regression, 35 (52%) used subgroup analyses, and 8 (12%) used both methods (Table 3). Among the 53 comparative reviews with a statistical comparison, 33 (62%) investigated heterogeneity. Five (15%) of the 33 reviews assessed the effect of potential confounders on relative accuracy using subgroup analyses (four reviews) or Bayesian bivariate meta-regression (one review).

Table 3.

Investigations of heterogeneity in comparative and multiple test reviews

| Characteristic | Comparative reviews |

Multiple test reviews | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical analyses to compare test accuracy | ||||

| Yes | No or unclear | |||

| Number of reviewsa | 53 (42) | 29 (23) | 45 (35) | 127 (100) |

| Formal investigation performed | ||||

| Yes—meta-regression and subgroup analyses | 5 (9) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 8 (6) |

| Yes—meta-regression | 15 (28) | 5 (17) | 4 (9) | 24 (19) |

| Yes—subgroup analyses | 13 (25) | 8 (28) | 14 (31) | 35 (28) |

| No—limited data | 8 (15) | 2 (7) | 1 (2) | 11 (9) |

| No—only tested for heterogeneity | 3 (6) | 8 (28) | 16 (36) | 27 (21) |

| No—nothing reported | 7 (13) | 5 (17) | 8 (18) | 20 (16) |

| Unclear | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| If yes above, was effect on relative accuracy also investigated? | ||||

| Yes | 5 (15) | 0 | 0 | 5 (15) |

| No | 21 (64) | 0 | 0 | 21 (64) |

| Planned but no data | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Unclear | 6 (18) | 0 | 0 | 6 (18) |

Numbers in parentheses are column percentages unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Numbers in parentheses are row percentages.

3.3. Presentation and reporting

Thirteen reviews (10%) used a reporting guideline (Table 4). Five reviews used PRISMA; four used QUORUM (Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses), the precursor to PRISMA; one used both QUORUM and PRISMA; one used both STARD (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy), and MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology); and the remaining two stated they followed recommendations of the Cochrane DTA Working Group.

Table 4.

Reporting and presentation characteristics of the reviews

| Characteristic | Comparative reviews |

Multiple test reviews | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical analyses to compare test accuracy | ||||

| Yes | No or unclear | |||

| Number of reviewsa | 53 (42) | 29 (23) | 45 (35) | 127 (100) |

| Reporting guideline used | 2 (4) | 5 (17) | 6 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Clear comparative objective stated | 45 (85) | 25 (86) | 0 | 70 (55) |

| Role of the tests | ||||

| Add-on | 6 (11) | 3 (10) | 2 (4) | 11 (9) |

| Replacement | 8 (15) | 6 (21) | 6 (13) | 20 (16) |

| Triage | 4 (8) | 1 (3) | 11 (24) | 16 (13) |

| Any two of the above | 4 (8) | 4 (14) | 2 (4) | 10 (8) |

| Unclear | 31 (58) | 15 (52) | 24 (53) | 70 (55) |

| Flow diagram presented | ||||

| Yes—included number of studies per test | 11 (21) | 6 (21) | 8 (18) | 25 (20) |

| Yes—excluded number of studies per test | 21 (40) | 12 (41) | 28 (62) | 61 (48) |

| No | 21 (40) | 11 (38) | 9 (20) | 41 (32) |

| Comparative studies identified | ||||

| Yes | 31 (58) | 9 (31) | 9 (20) | 49 (39) |

| No | 16 (30) | 7 (24) | 27 (60) | 50 (39) |

| No comparative studies in review | 6 (11) | 13 (45) | 9 (20) | 28 (22) |

| Study characteristics presented | 48 (91) | 26 (90) | 43 (96) | 117 (92) |

| Test comparison strategy | ||||

| Yesb | 19 (36) | 2(7) | 1 (2) | 22 (17) |

| Nob | 32 (60) | 20 (69) | 44 (98) | 96 (76) |

| No—included only comparative studies | 2 (4) | 7 (24) | 0 | 9 (7) |

| Method used for test comparisonc | ||||

| Yes | 48 (91) | NA | NA | 48 (91) |

| Unclear | 5 (9) | NA | NA | 5 (9) |

| 2 × 2 data for each study | 30 (57) | 10 (34) | 14 (31) | 54 (43) |

| Individual study estimates of test accuracy | 46 (87) | 25 (86) | 36 (80) | 107 (84) |

| Forest plot(s) | 30 (57) | 19 (66) | 16 (36) | 65 (51) |

| SROC plot | ||||

| SROC plot comparing summary points or curves for 2 or more tests | 19 (36) | 7 (26) | 2 (4) | 28 (22) |

| Separate SROC plot per test | 17 (32) | 11 (38) | 19 (42) | 47 (37) |

| No SROC plot | 17 (32) | 11 (38) | 24 (53) | 52 (41) |

| Limitations of indirect comparison acknowledged | ||||

| Yes | 13 (25) | 3 (10) | 2 (4) | 18 (14) |

| No | 30 (57) | 15 (52) | 43 (96) | 88 (69) |

| No but only comparative studies included | 10 (19) | 11 (38) | 0 | 21 (17) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SROC, summary receiver operating characteristic.

Numbers in parentheses are column percentages unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Numbers in parentheses are row percentages.

These reviews included both comparative and noncomparative studies.

These methods either involve a comparative meta-analysis or follow-on from a meta-analysis of each test individually.

3.3.1. Summary of reporting quality and exemplars

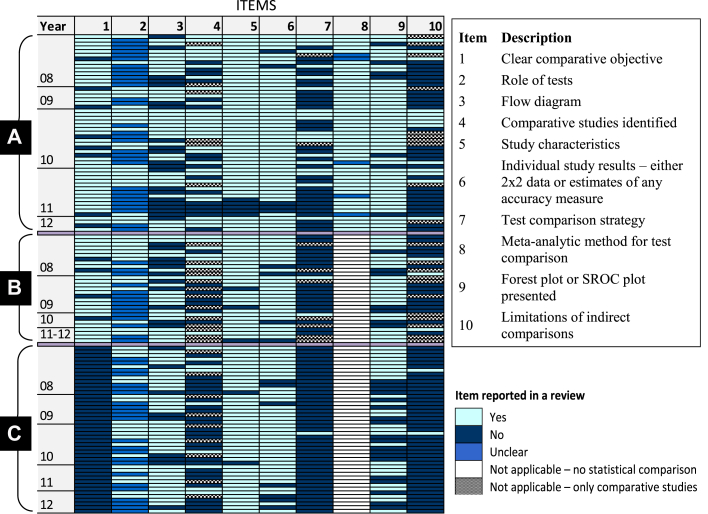

Based on recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook [12], five comparative reviews [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]] were judged exemplary in terms of clarity of objectives and reporting of test comparison methods. A brief summary of the reviews is given in Appendix Table 1. Fig. 2 summarizes results for 10 reporting characteristics (derived from Table 4) for each of the 127 reviews. The figure clearly shows that the reporting of several items—in particular the role of the index tests, test comparison strategy and limitations of indirect comparisons—was deficient in many reviews. Further details are provided in sections 3.3.2, 3.3.3, 3.3.4, 3.3.5, 3.3.6.

Fig. 2.

Reporting characteristics of 127 comparative and multiple test reviews. (A) Comparative reviews with statistical analyses performed to compare accuracy; (B) Comparative reviews without statistical analyses to compare accuracy; (C) Multiple test reviews. The colored cells in each row illustrate the reporting of the 10 items in each review. The box to the right of the figure gives the description of the reporting items. Reviews were ordered by year of publication and the number of missing items within each of the three review categories A to C. All multiple test reviews did not state a clear comparative objective (this was one of the four criteria used to classify the reviews as stated in section 2.1).

3.3.2. Review objectives and clinical pathway

A comparative objective was explicitly stated in 70 (55%) reviews (Table 4). It was possible to deduce the role of the tests in 57 (45%) reviews as add on, triage, and/or replacement for an existing test. For 28 of the 57 (49%) reviews, the role was explicitly stated while we used implicit information in the background and discussion sections to make judgments for the remaining 29 (51%) reviews.

3.3.3. Study identification and characteristics

A flow diagram illustrating the selection of studies was not presented in 41 (32%) reviews (Table 4). In 61 (48%) reviews, a flow diagram was presented without the number of studies per test, whereas 25 (20%) reviews presented a comprehensive flow diagram with the number of studies per test. Of these 25 reviews, the flow diagrams in five reviews [14,[18], [19], [20], [21]] were notable examples. These flow diagrams clearly showed the number of studies included in the analysis of each test, and also indicated the number of comparative studies available. Of the 99 reviews that had at least one comparative study, 50 (51%) reviews did not identify the comparative studies. Most of the reviews (92%) reported study characteristics; however, the detail reported varied.

3.3.4. Strategy for comparing test accuracy

Seventy-three comparative reviews included both comparative and noncomparative studies and 21 (29%) of these reviews stated their strategy for comparing tests, that is, direct and/or indirect comparisons (Table 4). Of the 21 reviews, 19 (90%) formally compared test accuracy.

3.3.5. Graphical presentation of test comparisons

An SROC plot showing results for two or more tests was presented in 28 (22%) reviews, 47 (37%) reviews showed each test on a separate SROC plot, and the remaining 52 (41%) reviews did not present an SROC plot (Table 4). Two multiple test reviews and seven comparative reviews without a formal test comparison presented an SROC plot showing a test comparison.

3.3.6. Limitations of indirect comparisons

Twenty-one (17%) reviews restricted inclusion to comparative studies (Table 4). Of the remaining 106 reviews that included any study type, 18 (17%) acknowledged the limitations of indirect comparisons. Furthermore, 9 of these 18 reviews recommended that future primary studies should directly compare the performance of tests within the same patient population.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

The findings of our methodological survey showed considerable variation in methods and reporting. Despite the importance of clear review objectives, they were often poorly reported and the role of the tests was ambiguous in many reviews. Comparative studies ensure validity by comparing like with like, thus avoiding confounding but only 16 reviews (13%) restricted study selection to comparative studies. This may be due to scarcity of comparative studies [4]. It is worth noting that only two tests were evaluated in most (81%) of the 16 reviews that restricted inclusion to comparative studies.

The strategy adopted for test comparisons (direct comparisons and/or indirect comparisons) was not specified in many reviews. Furthermore, the strategies that were specified varied considerably, reflecting a lack of understanding of the best methods for comparative accuracy meta-analysis. The validity of indirect comparisons largely depends on assumptions about study characteristics but reviews did not always report study characteristics. To pool data for a direct or indirect comparison, the hierarchical methods recommended for comparative meta-analysis were not often used, with many reviews using methods known to have methodological flaws that can lead to invalid statistical inference [12,[22], [23], [24]].

There are several potential sources of bias and variation in test accuracy studies [[25], [26], [27]], and investigations of heterogeneity were commonly performed. However, the analyses were often performed separately for each test rather than examining the effect jointly on all tests in a comparison. Understandably, the latter is rarely possible because of limited data. As empirical findings have shown that results of indirect comparisons are not always consistent with those or direct comparisons [4], and adjusting for potential confounders in an indirect comparison will be uncommon, review findings should be carefully interpreted in the context of the quality and the strength of the evidence. Nevertheless, reviews seldom acknowledged the limitations of indirect comparisons.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, a comprehensive overview of reviews of comparative accuracy across different target conditions and types of tests has not been undertaken. We thoroughly examined a large sample of reviews published in a wide range of journals. Our classification of reviews was inclusive to enable a broad perspective of the literature and the generalizability of our findings. In addition to documenting review characteristics, we highlighted examples of good practice that review authors can use as exemplars. We also expanded relevant PRISMA-DTA items for reporting test comparisons in a DTA review.

Our study has limitations. First, the most recent review in our cohort of reviews was published in October 2012. Because the PRISMA-DTA checklist was published in January 2018, we did not update the collection as there had been no prior developments in reporting to suggest more recently published reviews would be better reported than older reviews. DARE is based on extensive searches of a wide array of databases and also includes gray literature. Given that for a review to be included in DARE, it must meet certain quality criteria, the quality of the literature may be even poorer than we have shown. This view is supported by a study of 100 DTA reviews published between October 2017 and January 2018, which found that the reviews were not fully informative when assessed against the PRISMA-DTA and PRISMA-DTA for abstracts reporting guidelines [6]. Furthermore, we examined the use of six comparative meta-analysis methods that have been published since 2012 by checking their citations in Scopus [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. Only one of the methods [31] had been cited in a DTA review published in 2018. We also conducted a search of MEDLINE (Ovid) on July 31, 2019, to identify DTA reviews published in 2019 (Appendix 1). Of 151 records retrieved, 43 reviews met the inclusion criteria. The findings summarized in Appendix 1 show that test comparison methods and reporting remain suboptimal. Thus, our collection of reviews in this study reflects current practice.

Second, the assessment of the role of the tests was sometimes subjective and relied on the judgment of the assessor. Therefore, we only considered whether the item was reported or not, without assessing the quality of the description provided. We also discussed any uncertainty in a judgment before making a final decision.

4.3. Comparison with other studies

Previous research focused on systematic reviews of a single test or overview of any review type without detailed assessment of comparative reviews [6,34,35], specific clinical area [36,37], or specific methodological issue [[38], [39], [40]]. Mallett et al. [36] and Cruciani et al. [37] concluded that conduct and reporting of DTA reviews in cancer and infectious diseases was poor. In an overview of DTA reviews published between 1987 and 2009, 36% of reviews that evaluated multiple tests reported statistical comparative analyses [35]. Similarly, 42% of our reviews reported such analyses.

4.4. Guidance and implications for research and practice

In Box 1, we provide reporting guidance for test comparisons to augment the PRISMA-DTA checklist and facilitate improvements in the reporting quality of comparative reviews. The guidance can also be used by peer reviewers and journal editors to appraise comparative DTA reviews. The challenges of a DTA review and the added complexity of test comparisons necessitate clear and complete reporting because of their increasing role in health technology assessment and clinical guideline development. Space constraints in journals are not an excuse for poor reporting because many journals publish online supplementary files. We noted that 56 (44%) reviews used supplementary files to provide additional data and information. Tutorial guides should be developed to assist review authors in navigating and understanding the complexity of DTA review methods. The Cochrane Screening and Diagnostic Tests Methods Group have already made contributions by providing freely available distance learning materials and tutorials on their website.

Box 1. Guidance for reporting test comparisons in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy.

| Item | Description (PRISMA-DTA items)a | Rationale and explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Role of tests in diagnostic pathway (3, D1) | Test evaluation requires a clear objective and definition of the intended use and role of a test within the context of a clinical pathway for a specific population with the target condition. The intended role of a test guides formulation of the review question and provides a framework for assessing test accuracy, including the choice of a comparator(s) and selection of studies. The role of a test is therefore important for understanding the context in which the tests will be used and the interpretation of the meta-analytic findings. The existing diagnostic pathway and the current or proposed role of the index test(s) in the pathway should be described. A new test may replace an existing one (replacement), be used before the existing test (triage) or after the existing test (add-on) [9]. |

| 2 | Test comparison strategy [13] | Comparative studies are ideal but they are scarce [4]. An indirect between-study (uncontrolled) test comparison uses a different set of studies for each test and so does not ensure like-with-like comparisons; the difference in accuracy is prone to confounding because of differences in patient groups and study methods. Although direct comparisons based on only comparative studies are likely to ensure an unbiased comparison and enhance validity, such analyses may not always be feasible because of limited availability of comparative studies. Conversely, an indirect comparison uses all eligible studies that have evaluated at least one of the tests of interest thus maximizing use of the available data (see Appendix Fig. 1). If study selection is not limited to comparative studies and comparative studies are available, a direct comparison should be considered in addition to an indirect comparison. The direct comparison may be narrative or quantitative depending on the availability of comparative studies. |

| 3 | Meta-analytic methods (D2) | Hierarchical models which account for between-study correlation in sensitivity and specificity while also allowing for variability within and between studies are recommended for meta-analysis of test accuracy studies [8,12]. The two main hierarchical models are the bivariate and the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) models which focus on the estimation of summary points (summary sensitivities and specificities) and SROC curves, respectively (see Appendix Fig. 2) [41,42]. For the summary point of a test to have a clinically meaningful interpretation, the analysis should be based on data at a given threshold. For the estimation of an SROC curve, data from all studies, regardless of threshold, can be included. As such, test comparisons may be based on a comparison of summary points and/or SROC curves. For the estimation of an SROC curve using the HSROC model, one threshold per study is selected for inclusion in the analysis. If multiple cutoffs were considered, the description of methods should include how the cutoffs were selected and handled in the analyses. Methods have been proposed which allow inclusion of data from multiple thresholds for each study but the methods are yet to be applied to test comparisons. |

| 4 | Identification of included studies for each test [16] | Review complexity increases with increasing number of tests, target conditions, uses and/or target populations within a single review. Therefore, distinguishing between the different groups of studies that contribute to different analyses in the review enhances clarity. The PRISMA flow diagram can be extended to show the number of included studies for each test or group of tests if inclusion is not limited to comparative studies. The detail shown—individual tests or groups of tests, settings and populations—will depend on the volume of information and the ability of the review team to neatly summarize the information. If such a comprehensive flow diagram is not feasible, the studies contributing to the assessment of each test can be clearly identified in the manuscript in some other way. The source of the evidence should be declared by stating types of included studies. Studies contributing direct evidence should also be clearly identified in the review. |

| 5 | Study characteristics [17] | Relevant characteristics for each included study should be provided. This may be summarized in a table and should include elements of study design if eligibility was not restricted to specific design features. Heterogeneity is often observed in test accuracy reviews and differences between tests may be confounded by differences in study characteristics. Confounders can potentially be adjusted for in indirect test comparisons, though this is likely to be unachievable due to small number of studies and/or incomplete information on confounders. The effect of factors that may explain variation in test performance is typically assessed separately for each test. |

| 6 | Study estimates of test performance and graphical summaries e.g., forest plot and/or SROC plot [19] | It is desirable to report 2 × 2 data (number of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives) and summary statistics of test performance from each included study. This may be done graphically (e.g., forest plots) or in tables. Such summaries of the data will inform the reader about the degree to which study-specific estimates deviate from the overall summaries, as well as the size and precision of each study. It is plausible that study results for one test may be more consistent or precise than those of another test in an indirect comparison. In addition to forest plots, reviews may include SROC plots such as those shown in Appendix Figures 1 and 2. An SROC plot of sensitivity against specificity displays the results of the included studies as points in ROC space. The plot can also show meta-analytic summaries such as SROC curves (panel B in Appendix Fig. 2) or summary points (summary sensitivities and specificities) with corresponding confidence and/or prediction regions to illustrate uncertainty and heterogeneity, respectively (panel A in Appendix Fig. 2). Ideally, results from a test comparison should be shown on a single SROC plot instead of showing the results for each test on a separate SROC plot. Furthermore, for pairwise direct comparisons, the pair of points representing the results of the two tests from each study can be identified on the plot by adding a connecting line between the points such as in the plot shown in panel B of Appendix Fig. 1. |

| 7 | Limitations of the evidence from indirect comparisons [23,24] | This is only applicable for reviews that include indirect comparisons. Be clear about the quality and strength of the evidence when interpreting the results, including limitations of including noncomparative studies in a test comparison. The results of indirect comparisons should be carefully interpreted taking into account the possibility that differences in test performance may be confounded by clinical and/or methodological factors. This is essential because it is seldom feasible to assess the effect of potential confounders on relative accuracy. |

Related to the PRISMA-DTA item(s) indicated in parentheses.

Because long-term RCTs of test-plus-treatment strategies which evaluate the benefits of a new test relative to current best practice are not always feasible [43,44] and are rare [45], comparative accuracy reviews are an important surrogate for guiding test selection and decision-making. However, given the preponderance of indirect comparisons and paucity of comparative studies, there is a need to educate trialists, clinical investigators, funders, and ethics committees about the merit of comparative studies for obtaining reliable evidence about the relative performance of competing diagnostic tests.

5. Conclusions

Comparative accuracy reviews can inform decisions about test selection but suboptimal conduct and reporting will compromise their validity and relevance. Complete and unambiguous reporting is therefore needed to enhance their use and minimize research waste. We advocate using the guidance we have provided as an adjunct to the PRISMA-DTA checklist to promote better conduct and reporting of test comparisons in DTA reviews.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yemisi Takwoingi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Christopher Partlett: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Richard D. Riley: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Chris Hyde: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Jonathan J. Deeks: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgments

Y.T. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Postdoctoral Fellowship for this research project. J.J.D. is a United Kingdom NIHR Senior Investigator Emeritus. Both Y.T. and J.J.D. are supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Center. This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.007.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Horvath A.R., Lord S.J., St John A., Sandberg S., Cobbaert C.M., Lorenz S. From biomarkers to medical tests: the changing landscape of test evaluation. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;427:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McInnes M.D.F., Moher D., Thombs B.D., McGrath T.A., Bossuyt P.M., PRISMA-DTA Group Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takwoingi Y., Leeflang M.M., Deeks J.J. Empirical evidence of the importance of comparative studies of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:544–545. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehmoobad Sharifabadi A., Leeflang M., Treanor L., Kraaijpoel N., Salameh J.P., Alabousi M. Comparative reviews of diagnostic test accuracy in imaging research: evaluation of current practices. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:5386–5394. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salameh J.P., McInnes M.D.F., Moher D., Thombs B.D., McGrath T.A., Frank R. Completeness of reporting of systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy based on the PRISMA-DTA reporting guideline. Clin Chem. 2019;65:291–301. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.292987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leeflang M.M., Deeks J.J., Takwoingi Y., Macaskill P. Cochrane diagnostic test accuracy reviews. Syst Rev. 2013;2:82. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leeflang M.M., Deeks J.J., Gatsonis C., Bossuyt P.M. Cochrane diagnostic test accuracy working group. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:889–897. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bossuyt P.M., Irwig L., Craig J., Glasziou P. Comparative accuracy: assessing new tests against existing diagnostic pathways. BMJ. 2006;332:1089–1092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeks J.J., Bossuyt P.M., GGatsonis C., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. https://methods.cochrane.org/sdt/handbook-dta-reviews Accessed at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moses L.E., Shapiro D., Littenberg B. Combining independent studies of a diagnostic test into a summary ROC curve: data-analytic approaches and some additional considerations. Stat Med. 1993;12:1293–1316. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780121403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macaskill P., Gatsonis C., Deeks J.J., Harbord R.M., Takwoingi Y. Chapter 10: analysing and presenting results. In: Deeks J.J., Bossuyt P.M., Gatsonis C., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy version 1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; London: 2010. https://methods.cochrane.org/sdt/handbook-dta-reviews [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alldred S.K., Deeks J.J., Guo B., Neilson J.P., Alfirevic Z. Second trimester serum tests for Down's Syndrome screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD009925. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L.W., Fahim M.A., Hayen A., Mitchell R.L., Baines L., Lord S. Cardiac testing for coronary artery disease in potential kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008691. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008691.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennant M., Takwoingi Y., Pennant L., Davenport C., Fry-Smith A., Eisinga A. A systematic review of positron emission tomography (PET) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for the diagnosis of breast cancer recurrence. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–103. doi: 10.3310/hta14500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams G.J., Macaskill P., Chan S.F., Turner R.M., Hodson E., Craig J.C. Absolute and relative accuracy of rapid urine tests for urinary tract infection in children: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:240–250. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuetz G.M., Zacharopoulou N.M., Schlattmann P., Dewey M. Meta-analysis: noninvasive coronary angiography using computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:167–177. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-3-201002020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewald B., Ewald D., Thakkinstian A., Attia J. Meta-analysis of B type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro B natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of clinical heart failure and population screening for left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Intern Med J. 2008;38(2):101–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geersing G.J., Janssen K.J., Oudega R., Bax L., Hoes A.W., Reitsma J.B. Excluding venous thromboembolism using point of care D-dimer tests in outpatients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minion J., Leung E., Menzies D., Pai M. Microscopic-observation drug susceptibility and thin layer agar assays for the detection of drug resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:688–698. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucassen W., Geersing G.J., Erkens P.M., Reitsma J.B., Moons K.G.M., Büller H. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:448–460. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwig L., Macaskill P., Glasziou P., Fahey M. Meta-analytic methods for diagnostic test accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00099-c. discussion 131-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arends L.R., Hamza T.H., van Houwelingen J.C., Heijenbrok-Kal M.H., Hunink M.G., Stijnen T. Bivariate random effects meta-analysis of ROC curves. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(5):621–638. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08319957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma X., Nie L., Cole S.R., Chu H. Statistical methods for multivariate meta-analysis of diagnostic tests: an overview and tutorial. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(4):1596–1619. doi: 10.1177/0962280213492588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lijmer J.G., Mol B.W., Heisterkamp S., Bonsel G.J., Prins M.H., van der Meulen J.H. Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. JAMA. 1999;282:1061–1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutjes A.W., Reitsma J.B., Di Nisio M., Smidt N., van Rijn J.C., Bossuyt P.M. Evidence of bias and variation in diagnostic accuracy studies. CMAJ. 2006;174(4):469–476. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiting P., Rutjes A.W., Reitsma J.B., Glas A.S., Bossuyt P.M., Kleijnen J. Sources of variation and bias in studies of diagnostic accuracy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:189–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trikalinos T.A., Hoaglin D.C., Small K.M., Terrin N., Schmid C.H. Methods for the joint meta-analysis of multiple tests. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):294–312. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menten J., Lesaffre E. A general framework for comparative Bayesian meta-analysis of diagnostic studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:70. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyaga V.N., Aerts M., Arbyn M. ANOVA model for network meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(6):1766–1784. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyer A., Kuss O. Meta-analysis for the comparison of two diagnostic tests to a common gold standard: a generalized linear mixed model approach. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(5):1410–1421. doi: 10.1177/0962280216661587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma X., Lian Q., Chu H., Ibrahim J.G., Chen Y. A Bayesian hierarchical model for network meta-analysis of multiple diagnostic tests. Biostatistics. 2018;19(1):87–102. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen R.K., Cooper N.J., Quinn T.J., Lees R., Sutton A.J. Network meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies identifies and ranks the optimal diagnostic tests and thresholds for health care policy and decision-making. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willis B.H., Quigley M. The assessment of the quality of reporting of meta-analyses in diagnostic research: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahabreh I.J., Chung M., Kitsios G.D., Terasawa T., Raman G., Tatsioni A. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2012. Comprehensive overview of methods and reporting of meta-analyses of test accuracy. AHRQ publication no. 12-EHC044-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallett S., Deeks J.J., Halligan S., Hopewell S., Cornelius V., Altman D.G. Systematic reviews of diagnostic tests in cancer: review of methods and reporting. BMJ. 2006;333:413. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38895.467130.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruciani M., Mengoli C. An overview of meta-analyses of diagnostic tests in infectious diseases. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23(2):225–267. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naaktgeboren C.A., van Enst W.A., Ochodo E.A., de Groot J.A.H., Hooft L., Leeflang M.M. Systematic overview finds variation in approaches to investigating and reporting on sources of heterogeneity in systematic reviews of diagnostic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1200–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinnes J., Deeks J., Kirby J., Roderick P. A methodological review of how heterogeneity has been examined in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:1–113. doi: 10.3310/hta9120. [iii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiting P., Rutjes A.W., Dinnes J., Reitsma J.B., Bossuyt P.M., Kleijnen J. A systematic review finds that diagnostic reviews fail to incorporate quality despite available tools. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reitsma J.B., Glas A.S., Rutjes A.W., Scholten R.J., Bossuyt P.M., Zwinderman A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutter C.M., Gatsonis C.A. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med. 2001;20:2865–2884. doi: 10.1002/sim.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lord S.J., Irwig L., Bossuyt P.M. Using the principles of randomized controlled trial design to guide test evaluation. Med Decis Making. 2009;29:E1–E12. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09340584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lord S.J., Irwig L., Simes R.J. When is measuring sensitivity and specificity sufficient to evaluate a diagnostic test, and when do we need randomized trials? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:850–855. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrante di Ruffano L., Davenport C., Eisinga A., Hyde C., Deeks J.J. A capture-recapture analysis demonstrated that randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of diagnostic tests on patient outcomes are rare. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.