Abstract

Background

Whether the survival benefit of β-blockers in congestive heart failure (CHF) from randomized trials extends to patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 but not receiving dialysis] is uncertain.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study using administrative datasets. Older adults from Ontario, Canada, with incident CHF (median age 79 years) from April 2002 to March 2014 were included. We matched new users of β-blockers to nonusers on age, sex, eGFR categories (>60, 30–60, <30), CHF diagnosis date and a high-dimensional propensity score. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we examined the association of β-blocker use versus nonuse with all-cause mortality.

Results

We matched 5862 incident β-blocker users (eGFR >60, n = 3136; eGFR 30–60, n = 2368; eGFR <30, n = 358). There were 2361 mortality events during follow-up. β-Blocker use was associated with reduced all-cause mortality [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54–0.64]. This result was consistent across all eGFR categories (>60: adjusted HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.49–0.62; 30–60: adjusted HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55–0.71; <30: adjusted HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.73; interaction term, P = 0.30). The results were consistent in an intention-to-treat analysis and with β-blocker use treated as a time-varying exposure.

Conclusions

β-Blocker use is associated with reduced all-cause mortality in elderly patients with CHF and CKD, including those with an eGFR <30. Randomized trials that examine β-blockers in patients with CHF and advanced CKD are needed.

Keywords: β-blocker, CHF, mortality

ADDITIONAL CONTENT

An author video to accompany this article is available at: https://academic.oup.com/ndt/pages/author_videos.

INTRODUCTION

In the general congestive heart failure (CHF) population, β-blockers are well known to reduce mortality based on high-quality evidence from landmark clinical trials [1, 2]. Unfortunately, patients with CHF often have chronic kidney disease (CKD), with prevalence estimates ranging from 20% to 74% [3]. Advanced CKD in this setting [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2] is strongly associated with increased all-cause mortality [4–7]. This high-risk subset of patients is routinely excluded from heart failure therapeutic trials [8, 9]. As such, there is little direct evidence for heart failure therapies in patients with CHF and advanced CKD, and most evidence is extrapolated from patients without CKD or with Stages 1–3 CKD [10]. Studies to date showing the mortality benefit of β-blockers in CKD and CHF are limited by the small number of patients with advanced CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), and younger mean age of included patients compared with the real-world CHF/CKD population [2, 6, 10–19].

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a large retrospective cohort study among incident elderly patients with CHF and various stages of CKD to examine the association of β-blocker use versus nonuse with mortality. We hypothesized that β-blocker use would be associated with a lower risk of mortality across all CKD stages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and setting

We conducted a matched retrospective cohort study using administrative health care databases linked via unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Ontario, Canada. The study was conducted according to a prespecified protocol. The use of data in this project was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. The reporting of this study follows the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data guidelines for observational studies (Supplementary data, Appendix A) [20].

Data sources

Incident patients with CHF were identified from the ICES-derived CHF database using validated definitions. Within the database, a patient is defined as having CHF if he or she had one hospital admission, outpatient visit or emergency department visit with a CHF diagnosis followed within 1 year by a second record with a CHF diagnosis. This algorithm has a specificity of 97% for a diagnosis of CHF [21]. The Canadian Organ Replacement Register was used to identify patients with a history of chronic dialysis, or a history of a kidney or heart transplant (exclusion criteria). The Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, which contains all health claims for inpatient and outpatient physician services, was also used to identify a history of chronic dialysis. Baseline laboratory data were determined using the Gamma-Dynacare database. Gamma-Dynacare is a laboratory service provider that contains outpatient laboratory information for individuals who had bloodwork drawn at any of their 225 collection sites in Ontario. Serum creatinine concentrations from these data were used to calculate eGFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation [22]. Demographics and vital status information were obtained from the Ontario Registered Persons Database. Diagnostic and procedure information from all hospitalizations were determined using the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database. Diagnostic information from emergency room visits was determined using the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System. Medication data were obtained from the Ontario Drug Benefit Plan database, which contains highly accurate records of all outpatient prescriptions dispensed to patients ≥65 years [23]. Whenever possible, we defined patient characteristics and outcomes using validated codes (Supplementary data, Appendix B).

Study cohort

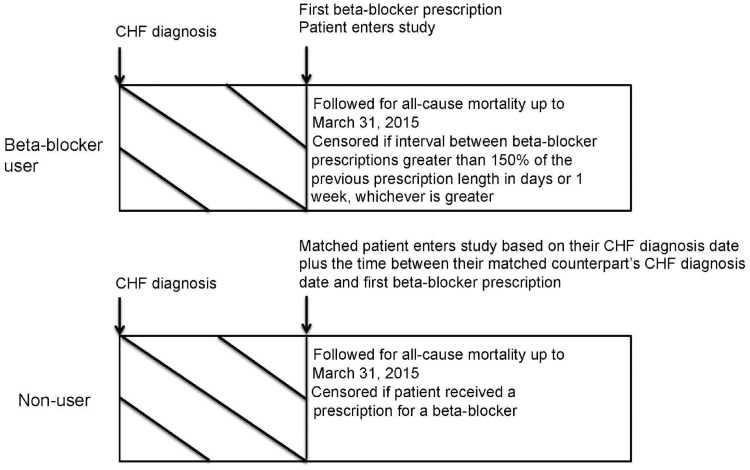

We included patients ≥66 years of age with an incident diagnosis of CHF from April 2002 to March 2014. We excluded patients without an eGFR measurement in the year prior to the CHF diagnosis date, those with a prior history of chronic dialysis, or kidney or heart transplantation, and patients with obvious contraindications to β-blocker therapy (bradycardia or pacemaker within 5 years prior to the CHF diagnosis date). To ensure that only incident β-blocker users were captured, patients with a prescription for a β-blocker in the 120 days prior to the CHF diagnosis date were excluded. The index date (date of entry into the study) for β-blocker users was the first date of a β-blocker prescription within 90 days after CHF diagnosis. β-Blocker users and nonusers were matched using a high-dimensional propensity score (HDPS). The HDPS is a computer algorithm designed for use in administrative databases that selects and ranks variables based on multiplicative bias testing (i.e. an empiric method of variable selection) [24]. Nonusers were assigned an index date post-matching; therefore, for the purposes of constructing the HDPS, nonusers were assigned a temporary index date created by randomly sampling the time in days from CHF diagnosis to index date for β-blocker users. This ensured that the final distribution of time between CHF diagnosis and index date would be the same between β-blocker users and nonusers. We then performed 1:1 matching using age (±2 years), sex, eGFR categories (>60, 30–60, <30), CHF diagnosis date (±2 years) and the logit of the HDPS (±0.2 times the SD). We hard matched on age, sex, eGFR and CHF diagnosis date, because differences can still persist following HDPS matching, and we wanted to ensure matching was achieved on these important variables. In addition, a nonuser was only matched to a β-blocker user if they were alive for at least 1 day after their matched counterpart’s index date. To mitigate the effect of immortal time bias, the index date for a nonuser coincided with the date that they received a diagnosis of CHF plus the time between their matched counterpart’s diagnosis of CHF and first β-blocker prescription (Figure 1) [25, 26].

FIGURE 1.

Study design. Timeline showing how β-blocker users and their matched counterparts were followed in the study.

β-Blocker use and outcomes

β-Blocker use was defined as receipt of a prescription for a β-blocker within 90 days of receiving a diagnosis of CHF (β-blocker list detailed in Supplementary data, Appendix C). β-Blocker nonusers had no evidence of a β-blocker prescription during the 90 days after CHF diagnosis. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Study participants were followed for death up to 31 March 2015. β-Blocker discontinuation was defined as the failure to refill or renew a β-blocker prescription within 150% of the time of the previous prescription length in days or 1 week, whichever was greater. Nonusers were censored at the time of receipt of first β-blocker prescription and β-blockers users were censored at discontinuation.

Other characteristics

Prior to matching, we assessed comorbidities, eGFR, albuminuria and measures of healthcare utilization in the 1 year prior to CHF diagnosis and concomitant medication use in the 120 days prior to CHF diagnosis. Following matching, we assessed comorbidities and measures of healthcare utilization in the 1 year prior to the index date, and eGFR and albuminuria 1 year prior to CHF diagnosis. Concomitant medications were assessed in the 120 days prior to the index date. We evaluated these conditions by searching the databases for codes of interest. We used database codes with proven accuracy whenever possible (see Supplementary data, Appendix B).

Statistical analysis

We used standardized differences to compare baseline characteristics between β-blocker users and nonusers. Standardized differences >0.1 were considered a significant difference between the two groups [27]. We calculated the crude event rate per 1000 person-years of follow-up by β-blocker use and eGFR categories (>60, 30–60, <30). We used Cox proportional hazards analysis to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for β-blocker use and all-cause mortality, treating β-blocker nonuse as the referent group. β-Blocker users and nonusers were censored as pairs [28]. We adjusted for the following characteristics: atrial fibrillation/flutter, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, anticoagulants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), amiodarone, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, loop diuretics, proton pump inhibitors, statins, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled β-agonists and inhaled glucocorticoids. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a P < 0.05 with two-sided testing.

Sensitivity analyses

Firstly, we performed an intention-to-treat analysis with follow-up restricted to 1 year. In this analysis, β-blocker exposure status was assigned at baseline, and patients were not censored if an exposure status change occurred. Second, we repeated the analysis treating β-blocker exposure as a time-varying covariate. Changes in β-blocker exposure status were defined as in the primary analysis, but patients were not censored upon exposure status changes. Third, we repeated the time-varying analysis with β-blocker users who discontinued their β-blocker within ≤30 days prior to death still treated as β-blocker users. This would mitigate bias potentially introduced by β-blocker discontinuation during end of life care.

To examine if the study outcome differed by the type of β-blocker, we created two groups: β-blockers with proven mortality benefit in large randomized trials (bisoprolol, metoprolol succinate, carvedilol; termed evidence-based β-blockers) and non-evidence-based β-blockers (metoprolol tartrate, atenolol and other). Lastly, to examine if patients not on angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), ACEi or aldosterone antagonists, potentially due to prior contraindication, also experienced a survival benefit with β-blockers, we repeated the survival analysis in a subgroup of patients not prescribed renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blocking medications.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Cohort selection is detailed in Supplementary data, Figure S1. From a total of 320 703 incident patients with CHF age ≥66 years, we identified 27 777 eligible patients with no prior evidence of β-blocker exposure. Prior to matching, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between β-blocker users (n = 7706) and nonusers (n = 20 071) (Supplementary data, Table S1). Following matching of β-blocker users to nonusers, there were 5862 pairs (eGFR >60, n = 3136 pairs; eGFR 30–60, n = 2368 pairs; eGFR <30, n = 358 pairs) with a mean age of 79 years. Minor differences in baseline characteristics persisted following matching (Table 1). The most commonly prescribed β-blocker at baseline was metoprolol (53%), followed by bisoprolol (30%). Carvedilol and atenolol were prescribed to a low proportion of patients (10% and 6%, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected baseline characteristics of the matched cohort a

| β-blocker user n = 5862 | Non user n = 5862 | Standardized difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at CHF diagnosis date | 79 (7.5) | 79 (7.5) | 0.002 |

| Female | 3007 (51) | 3007 (51) | 0 |

| Rural location | 617 (11) | 622 (11) | 0.003 |

| CHF diagnosis year (2002–05) | 994 (17) | 987 (17) | 0.01 |

| CHF diagnosis year (2006–09) | 2243 (38) | 2255 (39) | 0.005 |

| CHF diagnosis year (2010–13) | 2625 (45) | 2620 (45) | 0.007 |

| Time from CHF diagnosis to index date (days), median (IQR) | 12 (5–33) | 12 (5–33) | 0 |

| Comorbiditiesb | |||

| Hypertension | 4318 (74) | 4295 (73) | 0.009 |

| Diabetes | 2842 (49) | 2904 (50) | 0.02 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 249 (4) | 219 (4) | 0.03 |

| Coronary artery disease including angina | 3706 (63) | 3357 (57) | 0.12 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3051 (52) | 2657 (45) | 0.14 |

| Coronary revascularization | 603 (10) | 493 (8) | 0.06 |

| Ischemic stroke | 199 (3) | 285 (5) | 0.07 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1895 (32) | 1478 (25) | 0.16 |

| Tachyarrhythmia, excluding atrial fibrillation | 316 (5) | 206 (4) | 0.09 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 641 (11) | 967 (17) | 0.16 |

| Dementia | 1075 (18) | 1148 (20) | 0.03 |

| Measures of healthcare utilizationb | |||

| Cardiac stress test | 1236 (21) | 1249 (21) | 0.005 |

| Echocardiogram | 4037 (70) | 3866 (66) | 0.06 |

| Hospitalizations, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.01 |

| Visits with a cardiologist, median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0.10 |

| Primary care visits, median (IQR) | 11 (6–18) | 11 (7–18) | 0.07 |

| Medicationsc | |||

| Carvedilol | 573 (10) | – | – |

| Metoprolol | 3084 (53) | – | – |

| Bisoprolol | 1743 (30) | – | – |

| Atenolol | 323 (6) | – | – |

| Other β-blocker | 139 (2) | – | – |

| ACEi | 2191 (37) | 2737 (47) | 0.19 |

| ARB | 1220 (21) | 1226 (21) | 0.003 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 202 (4) | 248 (4) | 0.04 |

| Hydralazine | 21 (0.4) | 37 (0.6) | 0.04 |

| Nitrates | 380 (7) | 484 (8) | 0.07 |

| Digoxin | 348 (6) | 546 (9) | 0.13 |

| Amiodarone | 83 (1) | 250 (4) | 0.17 |

| Statins | 2428 (41) | 2726 (47) | 0.10 |

| Loop diuretics | 2006 (34) | 2725 (47) | 0.25 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 1269 (22) | 1357 (23) | 0.04 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2016 (34) | 2366 (40) | 0.12 |

| Inhaled anti-cholinergic | 568 (10) | 865 (15) | 0.16 |

| Inhaled glucocorticoid | 931 (16) | 1291 (22) | 0.16 |

| Inhaled β-agonist | 1111 (19) | 1543 (26) | 0.18 |

| Antiplatelets | 700 (12) | 898 (15) | 0.10 |

| Anticoagulants | 867 (15) | 1317 (23) | 0.20 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 1637 (28) | 1961 (34) | 0.12 |

| Laboratory measurementsd | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 62.0 | 62.0 | 0.006 |

| Median (IQR) | (47.0–77.0) | (48.0–77.0) | – |

| eGFR >60 | |||

| n (%) | 3136 (54) | 3136 (54) | 0 |

| Median (IQR) | 76 (68–84) | 75 (68–85) | 0.01 |

| eGFR 30–60 | |||

| n (%) | 2368 (40) | 2368 (40) | 0 |

| Median (IQR) | 48 (41–55) | 48 (41–54) | 0.01 |

| eGFR <30 | |||

| n (%) | 358 (6) | 358 (6) | 0 |

| Median (IQR) | 24 (19–27) | 24 (17–28) | 0.04 |

| Number of patients with ≥1 urine ACR measuremente | 1506 (26) | 1493 (26) | – |

| Urine ACR (mg/mmol) | 4.0 | 3.0 | 0.04 |

| Median (IQR) | (1.0–15.0) | (1.0–14.0) | – |

Continuous variables are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. Categorical variables are reported as n (%). Standardized differences >0.1 were considered statistically significant.

Measured 1 year prior to the index date.

Measured 120 days prior to the index date.

Measured 1 year prior to the CHF diagnosis date. The most recent value was recorded.

Urine ACR was only available in a subset of patients.

ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

β-Blocker use and all-cause mortality

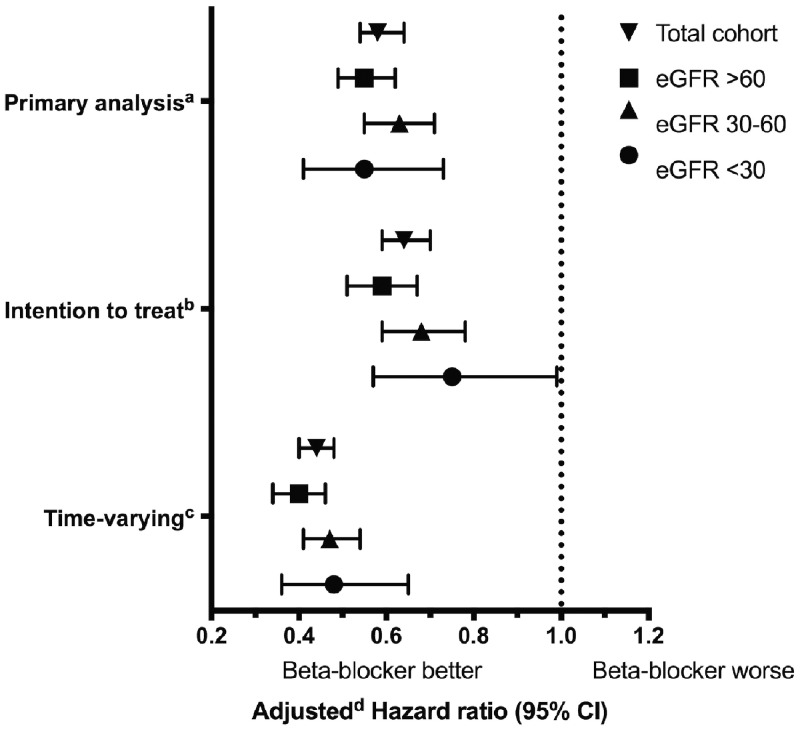

In total, there were 2361 mortality events, over a median (25th, 75th percentile) follow-up of 0.7 (0.2, 2.0) years. Crude event rates by β-blocker exposure status and eGFR categories are presented in Table 2. β-Blocker use was associated with reduced all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.54–0.64). The reduction in mortality was consistent across eGFR categories (eGFR >60: adjusted HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.49–0.62; eGFR 30–60: adjusted HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55–0.71; eGFR <30: adjusted HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.73; interaction term, P = 0.30) (primary analysis in Figure 2 and Table 3, unadjusted results in Supplementary data, Table S2).

Table 2.

Mortality events by β-blocker use

| β-blocker user |

Nonuser |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Median (25th, 75th percentile) follow-up (years) | IR (95% CI) per 1000 patient-years | n (%) | Median (25th, 75th percentile) follow-up (years) | IR (95% CI) per 1000 patient-years | IR ratio (95% CI) | |

| Total cohort | 937 (16) | 0.72 | 103.5 | 1424 (24) | 0.61 | 169.6 | 0.61 |

| (0.23, 2.05) | (96.8–110.1) | (0.17, 1.88) | (160.8, 178.4) | (0.56–0.66) | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | |||||||

| >60 | 424 (14) | 0.77 | 81.5 | 677 (22) | 0.65 | 141.5 | 0.58 |

| (0.24, 2.16) | (73.7–89.2) | (0.18, 1.98) | (130.8–152.1) | (0.51–0.65) | |||

| 30–60 | 435 (18) | 0.70 | 126.6 | 625 (26) | 0.59 | 194.1 | 0.65 |

| (0.23, 1.97) | (107.2–127.7) | (0.17, 1.84) | (153.3–173.1) | (0.57–0.73) | |||

| <30 | 78 (22) | 0.52 | 187.0 | 122 (34) | 0.45 | 311.5 | 0.60 |

| (0.20, 1.55) | (145.5–228.5) | (0.12, 1.38) | (256.2–366.8) | (0.43–0.77) | |||

IR, incidence rate.

FIGURE 2.

Mortality risk and β-blocker use. aPrimary analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined at baseline and matched pairs were censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes. bIntention-to-treat analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined at baseline; patients were not censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes. cTime-varying analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined using a time-varying model; patients were not censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes. dAdjusted for the following characteristics: atrial fibrillation/flutter, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, anticoagulants, ACEi, amiodarone, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, loop diuretics, proton pump inhibitors, statins, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled β-agonists and inhaled glucocorticoids.

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs for the primary, intention-to-treat and time-varying analyses

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)a Primary analysis | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a Intention-to-treat analysis | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a Time-varying analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 0.58 (0.54–0.64) | 0.64 (0.59–0.70) | 0.44 (0.40–0.48) |

| eGFR(mL/min/1.73 m2) | |||

| >60 | 0.55 (0.49–0.62) | 0.59 (0.51–0.67) | 0.40 (0.34–0.46) |

| 30–60 | 0.63 (0.55–0.71) | 0.68 (0.59–0.78) | 0.47 (0.41–0.54) |

| <30 | 0.55 (0.41–0.73) | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) | 0.48 (0.36–0.65) |

Primary analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined at baseline and matched pairs were censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes.

Intention-to-treat analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined at baseline; patients were not censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes.

Time-varying analysis: β-blocker exposure was determined using a time-varying counting process model; patients were not censored upon β-blocker exposure status changes.

Nonuser treated as the referent group. Adjusted for the following characteristics: atrial fibrillation/flutter, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, anticoagulants, ACEi, amiodarone, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, loop diuretics, proton pump inhibitors, statins, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled β-agonists and inhaled glucocorticoids.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings were consistent in sensitivity analyses. In an intention-to-treat analysis restricted to 1 year of follow-up, baseline β-blocker use was associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.59–0.70). The reduction in mortality was consistent across eGFR categories (eGFR <30: adjusted HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.99; interaction term, P = 0.20) (intention-to-treat analysis in Figure 2 and Table 3, unadjusted results in Supplementary data, Table S2).

In a model accounting for time-varying β-blocker exposure restricted to 1 year of follow-up, β-blocker use was associated with reduced all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.40–0.48). The mortality reduction was consistent across eGFR categories (eGFR <30: adjusted HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.36–0.65; interaction term, P = 0.20) (time-varying analysis in Figure 2 and Table 3, unadjusted results in Supplementary data, Table S2). Among β-blocker users at baseline, 71% remained on β-blockers at the end of the 1-year follow-up. This result was similar across eGFR categories (eGFR >60: 71%; eGFR 30–60: 72%; eGFR <30: 72%). Among nonusers at baseline, 10% were β-blocker users at the end of the 1-year follow-up (eGFR >60: 10%; eGFR 30–60: 11%; eGFR <30: 9%). A time-varying analysis ignoring β-blocker discontinuation events in the 30 days prior to death also demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality (eGFR >60: adjusted HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55–0.72; eGFR 30–60: adjusted HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.63–0.82; eGFR <30: adjusted HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58–1.02; interaction term, P = 0.30).

A mortality benefit was found with both evidence-based (adjusted HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.46–0.59; interaction term for eGFR category, P = 0.61) and non-evidence-based β-blockers (adjusted HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.59–0.74; interaction term for eGFR category, P = 0.26). However, a slightly greater mortality benefit was found with evidence-based β-blockers (interaction term for β-blocker type, P = 0.008). A subgroup analysis restricted to individuals not on ARB, ACEi or aldosterone antagonists demonstrated that β-blocker use was associated with reduced all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.42–0.61; interaction term for eGFR category, P = 0.07).

DISCUSSION

In this propensity-matched cohort of 11 724 elderly patients with incident CHF, we found a lower risk of all-cause mortality associated with β-blocker use. The mortality benefit of β-blockers was observed across all eGFR categories, including advanced CKD (eGFR <30). Our findings were consistent when β-blocker use was examined in intention-to-treat and time-varying analyses. Furthermore, our findings remained consistent when β-blocker use was examined by subgroup of evidence-based versus non-evidence-based, and in a subgroup of patients not taking ACEi, ARB or aldosterone antagonists.

While the relative reduction in mortality was similar across all eGFR categories, the overall mortality rate was highest in the eGFR <30 category, indicating a greater absolute mortality reduction in patients with advanced CKD. In theory, β-blockade should be particularly beneficial in these patients as both CHF and CKD result in sympathetic upregulation, and enhanced sympathetic activity has been linked to poor outcomes [11, 29–31].

Based on high-quality evidence from large randomized controlled trials, national cardiovascular guidelines recommend that patients with CHF with reduced ejection fraction (CHFrEF) be prescribed β-blockers to reduce mortality [32]. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II), Metoprolol CR/XL (controlled release/extended release) Randomized Intervention Trial in chronic Heart Failure (MERIT-HF), and The Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival (COPERNICUS) trials all demonstrated a mortality reduction with bisoprolol, metoprolol and carvedilol, respectively [1, 18, 19]. Smaller trials have demonstrated a reduction in composite outcomes that included mortality [33, 34]. Unfortunately, all randomized controlled trials largely excluded patients with CKD, limiting generalizability to such patients. CIBIS-II excluded patients with a creatinine ≥300 μmol/L, MERIT-HF excluded patients with ‘any serious disease that might complicate management and follow-up’ (87% of patients had an eGFR >45) and COPERNICUS excluded patients with a creatinine >248 μmol/L or an increase in creatinine >44.2 μmol/L during the screening period [1, 18, 19]. Data to support the efficacy of β-blockers in patients with CHF and CKD are largely based on post hoc randomized trial subgroup analyses [12, 14, 16]. Badve et al. performed a meta-analysis of the CKD subgroup results (CKD defined by an eGFR <60) from six randomized controlled trials that randomized patients with CHFrEF to placebo versus β-blocker. Upon meta-analysis, it was found that β-blockers significantly reduced mortality (relative risk 0.72, 95% CI 0.64–0.80) and the P-value for an interaction between CKD status and β-blocker effect was nonsignificant [10, 12]. However, these results were still limited by the fact that very few patients with advanced CKD (i.e. eGFR <30) were included in the analysis.

Prior observational studies that examined the mortality benefit of β-blockers in patients with CHF and CKD are also limited by the inclusion of few patients with an eGFR <30. Ezekowitz et al. reported that β-blockers were associated with reduced all-cause mortality in patients with CHF, coronary artery disease and a creatinine clearance (CrCl) of 30–59 mL/min (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68–0.97), but were not associated with reduced mortality in patients with a CrCl <30 mL/min [odds ratio (OR) 0.97, 95% CI 0.74–1.27]. The lack of mortality benefit in patients with advanced CKD may be due to a lack of power (CrCl <30 mL/min: n = 466; n= 242 β-blocker users), residual confounding or bias [6]. McAlister et al. reported a similar reduction in mortality associated with β-blocker use in patients with a CrCl <60 mL/min (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.23–0.70) and >60 mL/min (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.19–0.85), but lacked a sufficient number of patients with CrCl <30 mL/min (n = 118) to examine this subgroup [15]. Chang et al. examined β-blocker use as a time-varying exposure in patients with CHF and CKD and found that β-blockers were associated with reduced all-cause mortality, but this effect was attenuated upon adjustment for comorbidities and other cardiovascular medication use (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.51–1.12). Their result may be due to a lack of power (n = 668) since β-blocker use was associated with a significant reduction in a composite outcome of mortality or heart failure hospitalization. The effect of β-blockers in the eGFR <30 subgroup was not examined due to a low number of patients (n = 42) [13].

Our large cohort size and large number of events allowed us to determine whether the protective effect of β-blockers in older patients with CHF is modified by the presence of various stages of CKD. There are, however, a number of limitations to our study. We only included older patients, which may limit the applicability of our results to younger individuals with CHF; however, >80% of patients with CHF are >65 years of age [35]. Our cohort was limited to individuals who had an outpatient serum creatinine measurement at a single laboratory provider, which may introduce a selection bias. However, Gamma-Dynacare is the largest laboratory provider in Ontario (n = 225 sites), with facilities across the entire province. While we excluded patients with obvious contraindications to β-blockers based on variables available in our datasets, we could not account for all potential contraindications, and ultimately, we do not know why nonusers were not prescribed a β-blocker. Also, the exclusion of certain individuals during the matching procedure may reduce generalizability. Most importantly, the allocation of β-blockers was nonrandom, and therefore our observed associations may not be causal. Confounding may occur with healthier patients and patients receiving better care having a higher likelihood of receiving a β-blocker prescription. Furthermore, these patients may have greater long-term β-blocker adherence for various reasons, potentially introducing bias into the analysis. To reduce concerns about confounding and bias, we examined only incident β-blocker users, accounted for alterations in β-blocker exposure over time in the analysis, performed various sensitivity analyses and employed a rigorous HDPS matching procedure. HDPS matching has demonstrated improved covariate balance between matched groups and less biased treatment estimates when benchmarked to randomized control trials [24, 36, 37]. The fact that the protective effect observed in our study for all eGFR categories is similar to that observed in large CHF trials further strengthens the assertion that our results confer a true protective effect [2, 17–19]. It is, however, important to note that prior landmark CHF trials demonstrating a survival benefit of β-blockers were restricted to patients with CHFrEF, and the role of β-blockers for the treatment of CHF with preserved ejection fraction (CHFpEF) remains uncertain [38]. The lack of EF data is, therefore, an important limitation of our study. Prior observational studies in the general heart failure population restricted to patients with CHFpEF have demonstrated a survival benefit associated with β-blocker use [39–41], while randomized trials have failed to demonstrate a protective effect. However, available CHFpEF trials were underpowered with high loss to follow-up [41, 42]. Without EF data, we cannot determine if our observed survival benefit extends to all elderly patients with CHF and CKD or only those with CHFrEF. This is an area that requires further study. Lastly, while cardiovascular mortality would be a more specific outcome, there were concerns about the accuracy of cause-specific mortality in the available datasets. For this reason, we selected all-cause mortality, which would be free of any misclassification.

In conclusion, we found that β-blocker use associates with reduced all-cause mortality in elderly patients with CHF and CKD, including those with an eGFR <30. Studies show under prescribing of cardiovascular protective medications to patients with CKD, which may be partly explained by the historical exclusion of patients with advanced CKD from cardiovascular therapeutic trials [6, 8, 15]. Randomized trials that examine the morbidity and mortality benefits of β-blockers in patients with CHF and advanced CKD and the effect modification of preserved versus reduced EF are needed.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Western and Ottawa site. The ICES is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Core funding for ICES Western is provided by the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario (AMOSO), the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry (SSMD), Western University and the Lawson Health Research Institute (LHRI). The research was conducted by members of the ICES Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation team, at the ICES Ottawa and Western facilities, who are supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, AMOSO, SSMD, LHRI, CIHR or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. We acknowledge Nassim Mojaverian for her help with the analysis.

FUNDING

A.O.M. receives salary support from the KRESCENT Foundation and the McMaster Department of Medicine. This work was supported by research grants from the Kidney Foundation of Canada and St Joseph’s Research Institute Hamilton, ON, Canada. M.M.S. is supported by the Jindal Research Chair for the Prevention of Kidney Disease. A.X.G. is supported by the Dr Adam Linton Chair in Kidney Health Analytics. The funders of this study had no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A.O.M., M.M.S., A.X.G. and M.A.W. contributed to the study design and review of the manuscript. A.O.M. and M.M.S. drafted the first version of the manuscript. W.P. conducted the data analysis. A.O.M. had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the data analysis. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared. The results of this article have not been published previously in whole or in part, except in abstract format.

(See related article by Agarwal and Rossignol. Beta-blockers in heart failure patients with severe chronic kidney disease—time for a randomized controlled trial? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 728--731)

REFERENCES

- 1. Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB. et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1651–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Domanski MJ, Krause SH, Massie BM. et al. A comparative analysis of the results from 4 trials of beta-blocker therapy for heart failure: BEST, CIBIS-II, MERIT-HF, and COPERNICUS. J Card Fail 2003; 9: 354–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed A, Campbell RC.. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin 2008; 4: 387–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G. et al. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38: 955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Damman K, Valente MA, Voors AA. et al. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 455–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ezekowitz J, McAlister FA, Humphries KH. et al. The association among renal insufficiency, pharmacotherapy, and outcomes in 6,427 patients with heart failure and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 1587–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hillege HL, Nitsch D, Pfeffer MA. et al. Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation 2006; 113: 671–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX. et al. Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2006; 296: 1377–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Konstantinidis I, Nadkarni GN, Yacoub R. et al. Representation of patients with kidney disease in trials of cardiovascular interventions: an updated systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Badve SV, Roberts MA, Hawley CM. et al. Effects of beta-adrenergic antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1152–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aslam F, Haque A, Haque J. et al. Heart failure in subjects with chronic kidney disease: best management practices. World J Cardiol 2010; 2: 112–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castagno D, Jhund PS, McMurray JJ. et al. Improved survival with bisoprolol in patients with heart failure and renal impairment: an analysis of the cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study II (CIBIS-II) trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2010; 12: 607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang TI, Yang J, Freeman JV. et al. Effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and chronic kidney disease. J Card Fail 2013; 19: 176–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghali JK, Wikstrand J, Van Veldhuisen DJ. et al. The influence of renal function on clinical outcome and response to beta-blockade in systolic heart failure: insights from Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Chronic HF (MERIT-HF). J Card Fail 2009; 15: 310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Tonelli M. et al. Renal insufficiency and heart failure: prognostic and therapeutic implications from a prospective cohort study. Circulation 2004; 109: 1004–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wali RK, Iyengar M, Beck GJ. et al. Efficacy and safety of carvedilol in treatment of heart failure with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4: 18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. A randomized trial of beta-blockade in heart failure. The cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study (CIBIS). CIBIS Investigators and Committees. Circulation 1994; 90: 1765–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 353: 9–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: metoprolol CR/XL randomised intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999; 353: 2001–2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicholls SG, Quach P, von Elm E. et al. The REporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) Statement: methods for arriving at consensus and developing reporting guidelines. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0125620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z. et al. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2013; 33: 160–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C. et al. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 10: 67–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ. et al. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology 2009; 20: 512–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar S, de Lusignan S, McGovern A. et al. Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhage, and mortality in older patients with chronic kidney disease newly started on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a population based study from UK primary care. BMJ 2018; 360: k342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A. et al. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ 2010; 340: b5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 2009; 38: 1228–1234 [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Brien PC, Fleming TR.. A paired Prentice-Wilcoxon test for censored paired data. Biometrics 1987; 43: 169–180 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bakris GL, Hart P, Ritz E.. Beta blockers in the management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2006; 70: 1905–1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iyngkaran P, Anavekar N, Majoni W. et al. The role and management of sympathetic overactivity in cardiovascular and renal complications of diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2013; 39: 290–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang DY, Anderson AS.. The sympathetic nervous system and heart failure. Cardiol Clin 2014; 32: 33–45, vii [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail 2017; 23: 628–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial Investigators; Eichhorn EJ, Domanski MJ, Krause-Steinrauf H. et al. A trial of the beta-blocker bucindolol in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1659–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ. et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowie MR, Fox KF, Wood DA. et al. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: a population-based study. Eur Heart J 2002; 23: 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guertin JR, Rahme E, Dormuth CR. et al. Head to head comparison of the propensity score and the high-dimensional propensity score matching methods. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016; 16: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guertin JR, Rahme E, LeLorier J.. Performance of the high-dimensional propensity score in adjusting for unmeasured confounders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 72: 1497–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin N, Manoharan K, Thomas J. et al. Beta-blockers and inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system for chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 6: Cd012721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fukuta H, Goto T, Wakami K. et al. The effect of beta-blockers on mortality in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomized controlled studies. Int J Cardiol 2017; 228: 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gomez-Soto FM, Romero SP, Bernal JA. et al. Mortality and morbidity of newly diagnosed heart failure with preserved systolic function treated with beta-blockers: a propensity-adjusted case-control populational study. Int J Cardiol 2011; 146: 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bavishi C, Chatterjee S, Ather S. et al. Beta-blockers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2015; 20: 193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cleland JGF, Bunting KV, Flather MD. et al. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 26–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.