Abstract

The efficacy of minoxidil (MXD) ethanolic solutions (1%‐5% w/v) in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia is limited by adverse reactions. The toxicological effects of repeated topical applications of escalating dose (0.035%‐3.5% w/v) and of single and twice daily doses (3.5% w/v) of a novel hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin MXD GEL formulation (MXD/HP‐β‐CD) and a MXD solution were investigated in male rats. The cardiovascular effects were evaluated by telemetric monitoring of ECG and arterial pressure in free‐moving rats. Ultrasonographic evaluation of cardiac morphology and function, and histopathological and biochemical analysis of the tissues, were performed. A pharmacovigilance investigation was undertaken using the EudraVigilance database for the evaluation of the potential cancer‐related effects of topical MXD. Following the application of repeated escalating doses of MXD solution, cardiac hypertrophy, hypotension, enhanced serum natriuretic peptides and K+‐ion levels, serum liver biomarkers, and histological lesions including renal cancer were observed. In addition, the administration of a twice daily dose of MXD solution, at SF rat vs human = 311, caused reductions in the systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure of the rats (−30.76 ± 3%, −28.84 ± 4%, and −30.66 ± 5%, respectively, vs the baseline; t test P < .05). These effects were not reversible following washout of the MXD solution. Retrospective investigation showed 32 cases of cancer associated with the use of topical MXD in humans. The rats treated with MXD HP‐β‐CD were less severely affected. MXD causes proliferative adverse effects. The MXD HP‐β‐CD inclusion complex reduces these adverse effects.

Keywords: androgenic alopecia, ATP‐sensitive potassium channels, cell proliferation, minoxidil, toxicology

Abbreviations

- AGA

androgenetic alopecia

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- HR

heart rate

- MXD

minoxidil

1. INTRODUCTION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA), characterized by a progressive miniaturization of terminal scalp hair with a pattern distribution, is the most common cause of hair loss in adults.1 The etiology is considered to be multifactorial, involving a complex interplay among several genes, androgens, and environmental factors. Although the exact molecular mechanisms are not fully understood, an abnormal level of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a potent androgen, appears to be an important causative factor.1, 2 Indeed, the upregulation of the 5α‐reductase enzyme is required to convert testosterone into DHT and is a drug target.3, 4

Currently, only two treatments have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of male AGA5: finasteride, a 5α‐reductase inhibitor3, 6, 7 administrated at 1 mg daily, and topical minoxidil (MXD) formulations (2% solution, 5% solution, or 5% foam). The effectiveness of both drugs in improving the symptoms of the disease has been demonstrated in several well‐designed studies.8, 9 However, many side effects of finasteride have been reported, including sexual dysfunction,9, 10 hypersensitivity reactions, and breast enlargement.10

MXD (2,4‐diamino‐6‐piperidino‐pyrimidine‐3‐oxide) is a potent oral antihypertensive drug developed at the end of the 1980s which is now most often prescribed for AGA.11 The antihypertensive functions of MXD occur through its sulfate metabolite,12 MXD sulfate, which exerts its effects by opening ATP‐sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) in several tissues, including vascular smooth muscle cells, thereby causing relaxation similar to other KATP‐channel openers.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 However, antihypertensive treatment with MXD causes severe hypotension, cardiac hypertrophy, and fluid retention.18 One of these unwanted side effects, the hypertrichosis, has been exploited in the treatment of AGA. 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Although topical MXD is generally accepted (as shown in many studies), the literature indicates that its chronic use can cause hypotension and cardiovascular side effects, including tachycardia, minor left ventricular hypertrophy, palpitations, dizziness, and syncope.24, 25, 26 This suggests that, even when topically applied, it may be systemically absorbed, reaching pharmacologically active concentrations. Novel drug treatments and formulations are therefore under development.27 A web‐based review on MXD use points out that 2816 people reported side effects caused by MXD, 51 of whom (1.8%) reported syncope.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Rare cases of association between the topical application of MXD to a mother's scalp and fetal toxicity and malformations have also been described.30, 31, 32 When locally applied, MXD can be absorbed through the skin, causing multiple local and systemic pharmacological effects. Three children (aged 10‐14) with alopecia aerate, who were treated with 2% topical MXD solution twice a day for up to 1 month, developed palpitations after starting MXD treatment. This has also been observed in other cases.33, 34

In addition, the MXD solution currently used is responsible of contact dermatitis, which is associated with itching or irritation of the scalp.35 This event can be related to the high percentage of propylene‐glycol and ethanol used as vehicles in the solution. Moreover, MXD solution can cause bilaterally symmetrical growth of vellus hair in nontreated areas, such as on the cheek and sideburn areas, because of the handling of the liquid during treatment. These events may suggest that MXD has uncontrolled systemic effects. Several novel MXD formulations are under development from different laboratories.36, 37, 38

To improve the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of the currently used MXD formulation, a new aqueous alginate/hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin (HP‐β‐CD) MXD gel which does not contain ethanol or propylene‐glycol was developed in our laboratories. The new aqueous alginate/HP‐β‐CD MXD gel was developed for several technological characteristics.39 In our previous studies,40, 41 the new aqueous alginate/HP‐β‐CD GEL with 3.5% MXD showed greater improvements in hair counts and global imaging assessments than the currently used ethanol/propylene‐glycol 3.5% MDX solution. “In vivo” pharmacological investigations showed that the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL enhanced hair growth, hair length, and bulb diameter, as well as showing improvements in the mRNA levels of pharmacodynamic markers, such as AKT2 and the SUR2 and Kir6.1 subunits of the KATP channels, and downregulation of the androgen receptor gene.41 An “in vitro” study showed that both MXD (10−4 mol/L) formulations were equally effective in potentiating KATP currents. In summary, the new aqueous alginate/HP‐β‐CD GEL with 3.5% MXD has shown a favorable efficacy profile following topical use vs the ethanol/propylene‐glycol MXD solution.

In this study the tolerability and toxicology profile of the new aqueous alginate/MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL were evaluated in male rats and compared with those of the ethanolic/propylene‐glycol MXD solution. The dosing protocol of repeated escalating doses on the same rat was used to study the effects of increasing the MXD concentrations of both formulations, starting with 0.035% and 0.07%, corresponding to the therapeutic doses in humans, and increasing to 3.5% (w/v). The systemic cardiovascular effects associated with MXD topical application were evaluated by monitoring the heart rate (HR), QT intervals, T‐ and P‐wave amplitudes, systemic arterial pressure, and body temperature in freely moving laboratory animals using a telemeter biosensory system inserted in the abdominal cavity of the animal. In addition, at the end of treatment, cardiac evaluations, included parasternal long‐axis assessments (B‐mode) and short‐axis measurements (M‐mode) of the left ventricular diastolic and systolic volumes, stroke volume, cardiac output, wall thickness, ejection fraction, and fractional shortening, were performed using echocardiography analyses on the rats treated with both formulations, as well as those in the control group. Histopathological analysis of the tissues isolated from the MXD‐treated rats and serum biochemical evaluations for markers of toxicity were also performed. The effects of the treatments on cardiovascular ECG and arterial blood pressure were also investigated by topical application of single and twice daily doses of the two MXD formulations at 3.5% (w/v) concentrations, corresponding to rat vs human safety factors (SFs) of 155 and 311, respectively.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemical and pharmaceutical tools

MXD (2,4‐diamino‐6‐piperidino‐pyrimidine‐3‐oxide, M. W. 209.25, 99% purity), HP‐β‐CD (MS 0.65, M. W. 1396), and sodium alginate (NaAlg, viscosity 1% at 25°C and 500‐600 mPa s) were gifts of Farmalabor. The chemicals and salt reagents were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (Milan). The biological reagents were provided by Promega (C. N. N2511). All drugs were prescribed by local veterinarians for experimental use and provided by Murgiavet, Gioia del Colle.

2.2. Animal groups and treatments

The animal treatment was carried out according to Italian Legislative Decree No. 26 of 04 March 2014, and performed under the supervision of a local veterinary official. Using an operator‐blinded design, the animals were randomly assigned to each experimental condition. The protocol was approved by the Organisation for Animal Health of the University of Bari on 15 April 2019 (Prot. 34091‐x/10, 06 May 2019) and by the Minister of Health, Rome (No. 673/2019‐PR Prot. DGSAF0025334‐P‐04/10/2019, prog. 7307D.11).

The temperature of the laboratory animals was maintained at 22 ± 1°C, with a relative humidity of 50 ± 5% and a 12:12 hour light‐dark cycle; animals were maintained on a standard laboratory diet of 30 g per rat per day and water ad libitum. Moreover, during the study, the animals were observed for changes in body weight, ambulation, and behavior (brightness, alertness, and responsiveness), signs of lethargy, lack of grooming, guarding (abdominal and muscular), pale conjunctivae, and decreased food intake. The experiments were performed on male Wistar rats (Charles River S.p.A., Calco, Lecco) with an initial mean body weight of 360 ± 14 g and a final body weight of 450 ± 19 g at the end of topical treatment (total number of rats = 28). The humane endpoints for animal drop out and sacrifice were a change in body weight ≥10% and a change in rectal body temperature ≥4°C, persistent for more than 3 days. The primary endpoint of the study was a body weigh change ≥10% following any treatment. Body weight was evaluated in 24‐h‐fasted animals using digital analytical balances (AV114C, 500 g and 100 g; OHAUS corp.) and the data stored for further analysis.

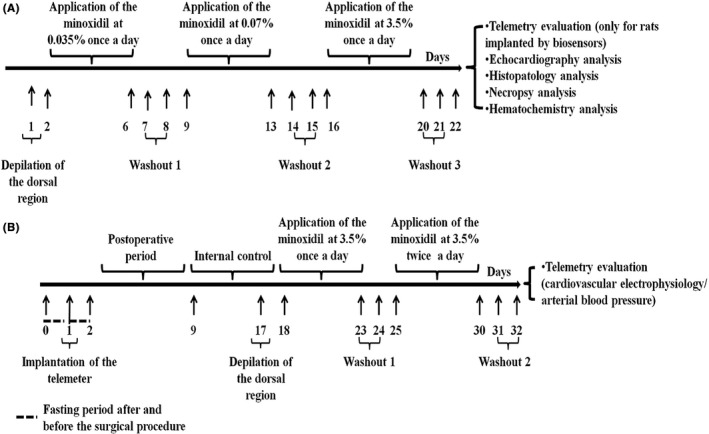

A repeated escalating dose of one of the two MXD formulations at concentrations of 0.035%, 0.07%, and 3.5% (w/v‐w) was administered once daily (Figure 1A). There were five groups of animals: 1A, rats receiving vehicle treatments with HP‐β‐CD GEL (number of rats = 5); 2A, rats receiving vehicle treatments with ethanol/glycol propylene solution (number of rats = 5); 3A, rats treated with MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL at 0.035% (0.777 mg/kg/day), 0.07% (1.554 mg/kg/day), and 3.5% (w/v‐w) (77.7 mg/kg/day) concentrations (number of rats = 7); and 4A, rats treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (number of rats = 7). Two rats per MXD‐treated group (3A and 4A) were used for telemetric monitoring of mean blood pressure and HR using this protocol.

FIGURE 1.

The first dosing protocol (A) was applied to evaluate the effects of escalating doses of minoxidil (MXD) on blood pressure in two rats per group, and on ultrasonographically evaluated cardiovascular functioning, and histopathological and biochemical parameters in five rats per group. The second dosing protocol (B) was applied to evaluate the effects of high doses of MXD on blood pressure and ECG parameters in two rats per group. Each 5‐day treatment period with the MXD formulations was followed by a 2‐day washout period to evaluate the reversibility of the observed blood pressure effects. Before starting treatment, each rat underwent an 8‐day recording period as an internal control for the evaluation of baseline values of the measured parameters. At the end of treatment, the animals were monitored for a further 2 days to evaluate the reversibility of the effects. The animals were then sacrificed, and the organs collected

Additionally, we evaluated the effects of the repeated topical application of 3.5% (w/v) concentrations of the two MXD formulations applied once daily, and twice daily at 6 hour intervals, on ECG and blood pressure parameters (rats per group = 2) (Figure 1B). There were two groups of animals: 1B, rats treated with MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL at 3.5% (w/v) (number of rats = 2) (77.7 mg/kg/day concentration); and 2B, rats treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution at 3.5% (w/v) (number of rats = 2).

The MXD 3.5% (w/v) solution (1 mL) was applied using a Pasteur pipette. The MXD 3.5% (w/w) GEL (1 g) was applied using a laboratory spatula. This corresponded to 35 mg (77.7 mg/kg/day) over 5 days of treatment and 70 mg (155.5 mg/kg/day) after an additional 5 days of treatment. Animal preparation was performed as described below; briefly, the dorsal area of the rats was shaved using an appropriate cream under moderate anaesthesia.41, 42 Starting 7 days after the surgical implantation of the telemeter in the rat abdominal cavity, BP and ECG measurements were collected continuously over a period of 8 days under baseline conditions (internal control conditions) in freely moving animals.

During the internal control, treatment, and washout periods, the rats were held in the SmartPad for intervals of 3‐12 hour to record their ECG and blood pressure signals. A washout period was planned to avoid any carryover effects related to the rapid pharmacokinetics of the MXD, and so that each experimental phase was not influenced by the previous one.

After the surgical procedure, a reduction in rat body weight by about 10% was observed, together with impaired motility. Within 5 days of the surgical procedure, the rats fully recovered their initial condition in terms of body weight, locomotion, and general behavior. The experimental animals were sacrificed at the end of treatment, under a saturated CO2 atmosphere, and following cervical dislocation; body weight data were collected and then the treated skin area, tissues, and organs were immediately extracted, washed in saline, and dried with filter paper. The tissues and organs were fixed in 10% formalin and thereafter used for histological analysis.

2.3. General anesthesia and surgical preparation

The general anesthesia was induced by intramuscular injections of Zoletil 50/50 (Pfizer) ip using three refracted doses of 20 mg/kg for a cumulative dose of 60 mg/kg. This drug induced a rapid and general anesthetic effect and complete muscle relaxation with no arrhythmias, avoiding the risk of epilepsy, and did not cause hepatic and/or renal toxicity in our experiments.42 Moreover, awakening was rapid, without spastic movements, and therefore without the risk of wounding the animals.

The animals were fasted for 24 hour before and after the surgical procedure. After injection of the anesthetic cocktail, the rat was placed on a heated surgical pad in dorsal recumbency. The surgical site was shaved and the skin was aseptically prepared using Hibitane, UK (8 g/L chlorhexidine gluconate) and ethanol (70%). The analgesic buprenorphine (10‐20 µg/kg s.c.) and the antibiotic enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg im) were administered for prophylactic reasons before the start of surgery at the induction of anesthesia, then the rat was draped with sterile gauze. During surgery the rat was closely monitored for the depth of its anesthesia.

2.3.1. Surgical procedure for BP catheter and ECG electrode implantation

The body of the implantable telemeter was positioned within the abdominal cavity and placed so that it would be parallel to the SmartPad when the rat was standing on all four legs. The telemeter was sutured to the abdominal muscle wall using both suture tabs (Figures S1 and S2). The ECG electrodes (constructed from a 1‐mm‐OD stainless steel spring and inserted into silicon tubing with a 5‐mm tip exposed) were tunneled subcutaneously. Briefly, one electrode was placed on the xiphoid process and the other was placed subcutaneously facing the head and then pushed along the trachea into the mediastinum region.43 In both cases, the end of the electrode was firmly sutured to the underlying tissue (https://millar.com/node/413).

2.3.2. ECG and systemic arterial pressure acquisition and analysis

The ECG and blood systemic arterial pressure signal from the implanted telemetry unit were received via a dedicated receiver (Telemetry Research). This signal was band‐pass filtered between 1 and 2000 Hz, and the reconstructed analogue signal was displayed using a PowerLab data acquisition system (sampling at 4000 Hz) with associated LabChart software (model ML870, ADInstruments). The signals were further analyzed using pre‐established/fixed algorithms within the Lab Chart 6 Pro Software. The ECG data were analyzed using ECG Analysis module software to assess HR, QT interval, and T‐wave amplitude and the BP data were analyzed using BP Analysis module software to assess the systolic, diastolic, and mean pressure. The data were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SD) for 15 min intervals. Each point was collected in one 30 min block, giving 5‐10 sampled points per observation period. To adjust for the rate, the corrected QT (QTc) was calculated by applying the Mitchell algorithm to the QT interval recordings: QTc = QT0/(RR/100)1/2.22. This algorithm is designed to correct for the higher HR and altered QRS‐T‐wave morphology of rodents. High‐amplitude ECG spiking was defined as sharp electrographic events three times the baseline voltage and counted using LabChart Spike Analysis within a 15 min bin. Movement artifacts were identified on the ECG and eliminated from the ECG analysis.

The ECG and BP data for each rat were grouped into three periods:

The baseline period used to evaluate the quality of transmitted data and the progress of ECG and BP in the absence of treatment;

The treatment period; and

The washout period.

Each period consisted of a temporal sequence of the average values of both variables under study each day. The daily mean was the result of a data file generated by LabChart software and related to a sampling file which considered 15 min recording blocks every 30 min throughout the period, starting 30 min after the topical application of the formulations investigated in this study. In addition, the associated SDs were calculated for each sample throughout the recording period. For each rat, the average value of both variables was first calculated for each day and then this mean was used to calculate the mean for the whole period (Figure S3).

2.4. Ultrasonographic evaluation

At the end of treatment, an ultrasonographic evaluation of cardiac structure and function was performed on control rats and rats treated with the formulations under investigation (rats per group = 5). At least 48 hour had elapse after the end of the previously described in vivo topical treatment to avoid any additional source of stress for the animals which could potentially influence the outcome of the ultrasound procedure. The ultrasonography experiments were conducted using the ultrahigh‐frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy system Vevo® 2100 (VisualSonics), which allows multiple image acquisition modes.44, 45, 46 The animals were properly prepared prior to each imaging session to allow optimal image acquisition. Each rat was anesthetized via inhalation (induced with ~3% isoflurane and l L/min 1.5% O2 and then constantly maintained via a nose cone at ~2% isoflurane and 1.5% O2) and placed on a thermostatically controlled table (kept at 37°C). Body temperature was carefully maintained between 37.0°C and 37.5°C. The table was equipped with four copper leads for monitoring both the heart and respiratory rate of the rat to minimize any physiological variation. Also, body temperature was monitored throughout the imaging session using a rectal probe. A petroleum‐based lubricant was used to cover the eyes to prevent drying. The thorax of the animal was properly shaved with depilatory cream to avoid any interference during image acquisition, and a small amount of preheated ultrasound gel was applied between the animal's skin and the probe to guarantee a proper image recording. At the end of the procedure the anesthetic influx was discontinued, and each animal was first cleaned with water, and then returned to its cage in the animal facility after briefly recovering from the anesthesia in an oxygenated box. Echocardiography was performed on the control and treated rats in bidimensional (B‐Mode) and monodimensional (M‐Mode) modes using a high‐resolution transducer at a frequency of 21 MHz (MS550). The images were acquired in a modified parasternal long‐axis view with the animal placed in a supine position. Briefly, after M‐mode image acquisitions, the LV M‐Mode trace was used to measure the ejection fraction (%), shortening fraction (%), stroke volume (µL), and cardiac output (mL/min). The left ventricular diastolic and systolic chamber internal diameter, posterior wall thickness, and intraventricular septum were also measured. Sample images of the left ventricle acquired in B (up) and M (down) mode are shown in Figure S4. Cardiac output was normalized for the body surface area of each rat. The left ventricle diameter in systole and diastole was calculated.47, 48

2.5. Serum biochemistry and electrochemistry

At the end of treatment, the animals were treated with the anesthetic agent and a 0.8 mL sample of the ventricular intracardiac blood was collected using a sterile microsyringe (1 mL) and an EDTA Vacutainer. The cardiac natriuretic peptides NT‐proANP and NT‐proBNP were evaluated using electrochemiluminescent assays, including the Rat Muscle Injury Panel 1 Assay, Rat NT‐proANP kit K153MBD, and Rat NT‐proBNP kit K153JKD from Meso Scale Discovery (MSD, Gaithersburg, MD).49 The serum samples were diluted 1:4 and 50 μL of diluted sample (for Rat NT‐proANP and Rat NT‐proBNP) was dispensed and tested in duplicate according to the manufacturer's protocol. After the completion of the procedure based on the MSD assay protocol, the plates were analyzed using an MSD Sector Imager, Model 2400. The average of the two values was used to report the final results. The serum biochemical assay was performed in a Chem Analyzer (Gesan) using appropriate operativity methodology such as turbidimetry and spectrophotometry. The reagents and kits for the veterinary biochemical assays were purchased from Gesan Production, Campobello di Mazara, TP, Italy.

2.6. Histopathology analysis

At the end of treatment, the animals were sacrificed by overdose of the anesthetic agent, followed by cervical dislocation, and the tissue samples were immediately preserved in 10% buffered formalin. The EDTA blood and serum were processed and analyzed for biochemistry. The histological examination was performed for each animal sample a minimum of 48 hour after fixation. The tissues and organs were embedded in paraffin, sections were cut into 5‐10 μm, and stained using standard techniques with hematoxylin and eosin. The histopathology and necropsy analysis included a gross/macroscopic and microscopic examination of the tissue samples, and organ assessment of the preserved heart, liver, kidneys, skin, and muscles. Finally, examination of the cellular morphology as well as intracellular structures was conducted. A histopathological scoring system, based on the semiquantitative ordinal system, was used to evaluate the severity of the observed lesions. The pathologist was blind to the treatment of the analyzed samples.50, 51 Images from 10 random fields were acquired for the 10 stained sections of each specimen using a D 4000 Leica DMLS microscope equipped with a camera and image analyzer, NIS‐elements BR (Nikon). The analysis of the sections was performed in Leica QWin software. Organ weigh was not evaluated to avoid possible damage to the tissues which were needed for the histological analysis.

2.6.1. Proliferative activity

For the evaluation of Ki‐67 proliferative activity in the kidney sections, a three‐layer biotin‐avidin‐peroxidase system was adopted. Briefly, 5‐μm‐thin serial sections were incubated with MIB‐1, an M7240 ki‐67 antigen (Dako). The bound antibodies were visualized using biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin‐biotin peroxidase complex, and 3‐amino‐9‐ethylcarbazole (Dako). Nuclear counterstaining was performed on each tissue sample, with Gill's hematoxylin (Polysciences). Data were expressed as the percentage of positive cells over the total number of cells in the section. The labeled Ki67‐positive cell population was measured by counting more than 100 Ki67‐positive cells per animal section, and was expressed as a percentage of proliferative activity in each tissue.

2.7. Pharmacovigilance investigation

The investigation on MXD‐associated cancer reactions was performed as previously described.52 The reactions list contained cancer, tumor, and neoplasm associated with the use of topical MXD for the treatment of alopecia. The EudraVigilance database from 2014 to 2018 was searched.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data from each animal were collected in electronic datasheets (Excel Software, Microsoft Office 10) and expressed as mean ± SE. Student t tests were used for statistical comparisons between means (P < .05). One‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple comparisons tests were applied (P < .05). The sample size for the rats undergoing the protocol reported in Figure 1A was calculated using a one‐way ANOVA on the primary endpoint of a body weigh change ≥10% of the mean between groups by the end of treatment. Using G*Power 3.1 software, we calculated a sample size of 20 rats, five per experimental group (four experimental groups), and a power of 0.98. In accordance with the 3R statement, this calculation did not include the animals used for the telemetry investigation, which were kept to a minimum (two rats per experimental group) considering that each animal was its own control.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Telemetric evaluation of blood pressure and HR, and ultrasonographic evaluation of cardiac function and morphology following the topical administration of repeated escalating doses of two MXD formulations at 0.035%, 0.07%, and 3.5% (w/v) once daily in male rats

The application of therapeutic doses of MXD 0.035% and 0.07% w/v to the dorsal area of the rats once daily did not significantly change the mean arterial blood pressure or HR vs the baseline (Figure 2), as observed in either of the treated rats (rats per group = 2) (Figure 1A). The application of repeated high doses of MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (3.5% w/v) at SF rat vs human = 155, however, significantly reduced the mean blood pressure vs baseline in both of the treated rats, as evaluated by a Student t test (P < .05, period of treatment 1 vs baseline). In contrast, no significant changes were observed following the treatment of the rats with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, as observed in both treated rats (rats per group = 2) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mean blood pressure (mmHg) following topical administration of the minoxidil (MXD) ethanol/glycol propylene solution (rats per group = 2) and the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation (rats per group = 2) in male rats. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n sampling time points (≥4000) collected during the daily recording of individual rats during 5 days of treatment and monitoring. Statistically significant changes were detected in the mean blood pressure of the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution vs the baseline at 3.5% w/v dose, as evaluated by a Student paired t test (P < .05). No significant changes to this parameter were observed in the rats following the application of the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation

We therefore investigated the effects of repeated escalating doses of the MXD formulations and their relative vehicles on cardiac function and morphology. Heart structure and function were evaluated by echocardiography in rats treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution, MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, and their relative vehicles (rats per group = 5). Significant enhancements of the systolic (30.23%) and diastolic (18.24%) left ventricle diameter, systolic (89.91%) and diastolic (45.8%) left ventricle volume, stroke volume (30.9%), left ventricle mass (33.71%), and systolic (36.32%) and diastolic (20.89%) left ventricle internal diameter were observed in the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (Figure 3A‐E). In the rats treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, we observed significant, but less pronounced, enhancements of the systolic (19.17%) and diastolic (14.93%) left ventricle diameter, diastolic (37.03%) left ventricle volume, stroke volume (31.4%), left ventricle mass (10.28%), and systolic (22.32%) and diastolic (19.25%) left ventricle internal diameter (Figure 3A‐E). No significant variations were observed for the other ultrasonographic parameters under investigation (data not shown). The rats in neither vehicle group showed significant abnormality.

FIGURE 3.

Cardiac ultrasonographic parameters obtained from control rats and rats treated with repeated escalating doses of the minoxidil (MXD) ethanol/glycol propylene solution (MXD solution), the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation (MXD GEL) (0.035%‐3.5% w/v), and their relative vehicles, once daily. (A) left ventricle diameter in systole (D, s) and diastole (D, d); (B) left ventricle volume in systole (V, s) and diastole (V, d); (C) left ventricle internal diameter in systole (LVID, s) and diastole (LVID, d); (D) stroke volume; (E) left ventricle mass (LVmass). Each bar is the mean ± SE. *Significantly different with respect to relative vehicle group (unpaired Student's t test, P < .05; rats per group = 5)

3.2. Body weight changes, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry of organs following the topical administration of repeated escalating doses of two MXD formulations (0.035%‐3.5% w/v) once daily in male rats

At the end of the treatment period (Figure 1A), we found that the animal groups treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and relative vehicle showed significantly reduced body weights of 400.2 ± 15 g and 420.4 ± 18 g, respectively (rats per group = 5; one‐way ANOVA, F = 3.23), vs the animal groups treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL and its relative vehicle which showed body weights of 440.3 ± 19 g and 460.4 ± 19 g, respectively (rats per group = 5).

The histological analysis performed at the end of the treatment on the rats treated with escalating doses of either the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution or the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, showed a notable inflammatory mononuclear presence in different organs vs the control condition (rats per group = 5). The histological analysis revealed that in both animal groups the treatment caused significant lesions in the following organs: the kidneys, liver, and skeletal and cardiac muscles, with no effects in dermal tissues. All five of the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution showed lesions in all the organs sampled (Figure 4). Three of the five rats treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation showed lesions in all the organs sampled. Liver (Figure 4, panels: 6‐7), kidney (Figure 4, panels: 1‐5), heart (Figure 4, panels: 8‐9), and skeletal muscle (Figure 4, panels: 10‐11) lesions were observed in three rats treated with the ethanol/glycol propylene vehicle solution, while one rat showed only liver lesions. Liver, kidney, and skeletal muscle lesions were observed in two rats treated with the HP‐β‐CD GEL vehicle. Lesions in other tissues which were not sampled cannot be excluded. The degree of the lesions was more elevated in rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and in its relative vehicle than in those treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation and its relative vehicle (Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Histopathological samples of the tissue lesions induced by treatment with escalating doses of minoxidil (MXD) ethanol/glycol propylene solution in the rats (0.035%‐3.5% w/v) once daily. The digitally captured images show histological sections of the kidney (image 1‐5 and 12), liver (6‐7), myocardium (8‐9), and skeletal muscle (10‐11) of rats treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution. The sections have been divided into quadrants of 1 cm2 and the values for each quadrant were calculated based on a histopathological scoring system (see Methods). Images were captured at 40× magnification. Kidney: The rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution show areas of mesangio‐capillary glomerulonephritis characterized by hypercellularity due to endothelial and mesangial proliferation and light capsular thickening (image 1) or semi‐moon formations between the capillary ball and bowman capsule (image 2). Interstitial‐type deformities with interstitial and papillary mononuclear cell inflammation (image 3) and tubular necrosis (image 4) were also observed. In some cases, there is evidence of one tubular microcarcinoma with an acinar appearance, characterized by a clear increase in tumor cell volume, large nuclei (double arrows in image 5), and mitotic activity (single arrow in image 5). In these samples, immunestaining with Ki‐67 also highlighted a positive result in the papillary duct (single arrow in image 12). Liver: The rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution show liver cells with steatosis phenomena, enlarged due to the presence of optically empty macro‐ and microvesicles. Widespread areas of chronic hepatitis, with widespread lymphocytic infiltration of portal spaces (image 6) and lobules, which may surround necrotic areas were observed (image 7). Myocardium: Heart hypertrophy and severe myocarditis were observed in the rats treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution, and to a lesser degree, in the rats treated with the MXD GEL formulation. Myofibrils with sarcoplasmic vacuolations (image 8) and exudate characterized by inflammatory mononuclear cells causing tissue disorganization, were reported (image 9). Skeletal muscle: In the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution, the endomysium and perimysium were widely infiltrated by inflammatory cells like macrophages and lymphocytes, and serous exudate was observed (image 10). Hypertrophic myofibrils with eosinophilic cytoplasm and vacuoles were also reported (image 11)

TABLE 1.

Histopathological description and severity grading following treatment with repeated escalating doses of two minoxidil (MXD) formulations (0.035%‐3.5% w/v), and their relative vehicles, once daily in the rats

| Organ | Type of injury | Description | Hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL treatment | MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL treatment | MXD ethanol/glycol propylene treatment | Ethanol/glycol propylene treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Circulation disorders | Congestion | + | + | ++ | + |

| Nephrosis | Glomerulonephrosis | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | |

| Tubulo‐nephrosis | + | + | +++ | + | ||

| Nephritis | Glomerulonephritis | + | + | ++ | + | |

| Tubulo‐interstitial nephritis | ‐ | + | ++ | + | ||

| Neoplasia | ‐ | + | +++ | + | ||

| Liver | Circulation disorders | + | + | +++ | + | |

| Regressive alterations | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

| Hepatitis | ‐ | + | ++ | ++ | ||

| Cholangitis | ‐ | + | + | + | ||

| Heart | Regressive alterations | ‐ | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Hypertrophy | ‐ | ++ | +++ | + | ||

| Myocarditis | ‐ | ++ | +++ | + | ||

| Skeletal muscle | Regressive alterations | + | + | ++ | + | |

| Myositis | ‐ | + | ++ | ++ | ||

| Skin | Dermatitis | ‐ | ‐ | + | ‐ |

A histopathological score based on the ordinal system was reported (rats per group = 5).

Immune staining of the kidney section with Ki‐67 was performed to evaluate the proliferative status of the cells. We found that 85.2 ± 1% and 38.3 ± 2% of the cells in the analyzed sections (five sections per organ) were positive for the antibody reaction following treatment with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (Figure 4, panel: 12) and the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, respectively.

3.3. Serum biomarkers following topical application of repeated escalating doses of two MXD formulations (0.035%‐3.5% w/v) once daily in male rats

The rats which were histopathologically positive also showed biochemical abnormalities. In the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (rats per group = 5), a significant enhancement in the serum ALP, GPT, and GOT levels was observed, as evaluated by one‐way ANOVA (Table 2) (P < .05; F = 1.62). Both formulations caused significant enhancement of the serum natriuretic peptide and K+ ions levels vs the affected rats in other groups (P < .05; F = 1.31). The ethanol/glycol propylene solution treatment significantly enhanced the serum ALP, GPT, GOT, CK, and NT‐proANP levels in four rats (P < .05; F = 1.32). The unaffected rats treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation and its relative vehicle showed biochemical parameters similar to control animals (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Serum biomarkers following the topical application of escalating doses of two minoxidil (MXD) formulations with concentrations ranging from 0.035% to 3.5% (w/v) in rats

| Analytes | MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution N rats = 5 | MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation N rats = 2 | Hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation N rats = 3 | Ethanol/ glycol propylene solution N rats = 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urea (mg/dL) | 18.1 ± 1 | 22.5 ± 0.4 | 21.1 ± 2 | 15.1 ± 2 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.2 ± 1 | 3.2 ± 2 | 4.1 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 1 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.02 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.02 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.9 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 231.1 ± 34 | 222.6 ± 32 | 228.4 ± 28 | 224.3 ± 31 |

| Glutamate pyruvate transaminase (U/L) | 253.3 ± 19* | 89.2 ± 10 | 92.8 ± 13 | 212.3 ± 31* |

| Creatinine (mg/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.01 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 245.8 ± 31* | 101.8 ± 23 | 92.1 ± 38 | 221.8 ± 28* |

| Globin (g/dL) | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 5 ± 0.2 |

| Uric acid (mg/mL) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 290.4 ± 39* | 68.7 ± 12 | 99.5 ± 2 | 280.2 ± 29* |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 800.2 ± 21* | 201.2 ± 29 | 170.3 ± 32 | 651.3 ± 28* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 116.4 ± 33 | 102.6 ± 22 | 89.3 ± 21 | 118.4 ± 23 |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 5 ± 0.6 | 4 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 6.9 ± 1 | 8.2 ± 3 | 5.9 ± 2 | 6.2 ± 0.1 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 7.8 ± 2 | 6.3 ± 2 | 6.2 ± 2 | 7.2 ± 3 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 72.1 ± 18 | 79.7 ± 35 | 92.2 ± 7 | 79.3 ± 19 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 8.7 ± 1* | 6.9 ± 2* | 4.8 ± 1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 163.8 ± 12 | 153.3 ± 5 | 158.1 ± 13 | 158.9 ± 11 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 79.2 ± 13 | 84.2 ± 13 | 96 ± 11 | 69.3 ± 11 |

| Natriuretic peptide (ng/mL) | 101.3 ± 31* | 69.18 ± 11* | 18.4 ± 1 | 67.3 ± 38* |

| Natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 531.21 ± 31* | 101.45 ± 30* | 23.3 ± 3 | 45.2 ± 32 |

The mean of the parameters was reported for the affected rats.

Data significantly different from other groups as evaluated by one‐way ANOVA (P < .05).

In conclusion, the treatment of the rats with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and the HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation significantly affected their ultrasonographic cardiovascular functioning and morphology, the histopathology of their tissues, and biochemistry markers. The MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution‐treated rats were severely affected. The arterial blood pressure was reduced in the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution‐treated rats at the highest dose tested (3.5% w/v) but not in the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL‐treated rats. We therefore additionally investigated the effects of higher doses of the MXD formulations (Figure 1B) (rats per group = 2) on the ECG parameters and blood pressure of freely moving rats.

3.4. Electrophysiological ECG parameters, blood pressure, and HR following topical application of repeated single and twice daily doses of two MXD formulations (3.5% w/v) in male rats

The topical administration of a single daily dose of MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution at 3.5% (w/v) concentration (SF rat vs human = 155) caused significant reductions of −22.52 ± 9%, −22.89 ± 8%, and −23.04 ± 9% of the systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure, respectively, vs the baseline, as evaluated by Student paired t tests (P < .05, period of treatment 1 vs baseline) (Figure 1B). The application of twice daily doses of this MXD formulation (SF rat vs human = 311) caused further significant reductions of −30.76 ± 3%, −28.84 ± 4%, and −30.66 ± 5% of the systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure, respectively, vs the baseline (P < .05 period of treatment 2 vs baseline) (Figure 5A). The washout period at the end of treatment 2 failed to restore the arterial blood pressure to the baseline value in the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution. Subsequently, the effects were not reversible at the end of treatment.

FIGURE 5.

Time course of changes in mean blood pressure (mmHg), systolic pressure (mm Hg), and diastolic pressure (mm Hg) of rats following topical administration of the minoxidil (MXD) ethanol/glycol propylene solution (A) (rats per group = 2) and the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation (B) (rats per group = 2). Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n sampling time points (≥4000) collected during the daily recording of individual rats. Statistically significant changes in mean blood pressure were detected for the rat treated with MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution vs the baseline, as evaluated by Student paired t test (P < .05). No significant changes were observed following the application of the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation

In contrast, the application of the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation (Figure 5B) caused mild and insignificant reductions in the systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure vs baseline (t test, P > .05, periods of treatments 1 and 2 vs baseline).

No changes in the systolic, diastolic, or mean blood pressure were observed in any of the experimental animals during the baseline period of 8 days (t test, P > .05). Hypotensive events appeared with a frequency of +28.57% following treatment with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and +14.28% after treatment with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation. The changes in blood pressure were observed starting from the third day of MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution application and from the sixth day of MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation application. The rats treated with both MXD formulations showed mild and insignificant increases in HR frequency (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Time course of changes in the heart rate (HR) of rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution (rats per group = 2) and MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation (rats per group = 2). Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n sampling time points (≥4000) collected during the daily recording of individual rats. No significant changes were observed following the application of the MXD hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation vs the baseline, as evaluated by Student paired t test (P < .05)

A significant decrease in the QTc interval and a depression of the ST segment were observed following treatment with once and twice daily doses of MXD 3.5% (w/v‐w) in treatment periods 1 and 2 in the rats treated with either MXD formulation (Figure 7, Table 3) (P < .05, periods of treatments 1 and 2 vs baseline). In addition, treatment with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution caused an enhancement of the T amplitude following treatment periods 1 and 2 vs baseline (P < .05, periods of treatments 1 and 2 vs baseline).

FIGURE 7.

Sample trace of cardiac action potentials in rats

TABLE 3.

Cardiac action potential parameters following treatment with two minoxidil (MXD) formulations

| Baseline | Treatment period 1 | Washout period | Treatment period 2 | Washout period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rats treated with the MXD 3.5% ethanol/glycol propylene solution | |||||

| P duration (s) | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.011 ± 0.006 | 0.016 ± 0.005 |

| QRS interval (s) | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.016 ± 0.002 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 0.012 ± 0.005 | 0.012 ± 0.006 |

| QT interval (s) | 0.047 ± 0.007 | 0.059 ± 0.001 | 0.063 ± 0.004 | 0.021 ± 0.008 | 0.064 ± 0.007 |

| QTc (s) | 0.067 ± 0.003 | 0.045 ± 0.003 | 0.047 ± 0.005 | 0.044 ± 0.009 | 0.049 ± 0.008 |

| P amplitude (mV) | 0.054 ± 0.006 | 0.099 ± 0.04* | 0.099 ± 0.003* | 0.038 ± 0.009 | 0.101 ± 0.009* |

| R amplitude (mV) | 1.015 ± 0.06 | 0.941 ± 0.04 | 0.841 ± 0.004 | 1.094 ± 0.03 | 0.916 ± 0.08 |

| S amplitude (mV) | −0.539 ± 0.07 | −0.496 ± 0.06 | −0.467 ± 0.020 | −0.554 ± 0.04 | −0.497 ± 0.04 |

| ST height (mV) | 0.183 ± 0.06 | 0.054 ± 0.005 | 0.053 ± 0.007 | 0.124 ± 0.05 | 0.092 ± 0.002 |

| T amplitude (mV) | 0.076 ± 0.008 | 0.113 ± 0.06 | 0.189 ± 0.005 | 0.266 ± 0.03 | 0.232 ± 0.001 |

| Rats treated with the MXD 3.5% hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin GEL formulation | |||||

| P duration (s) | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.018 ± 0.02 | 0.018 ± 0.003 | 0.015 ± 0.005 |

| QRS interval (s) | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 0.016 ± 0.03 | 0.016 ± 0.002 | 0.016 ± 0.006 |

| QT interval (s) | 0.054 ± 0.004 | 0.058 ± 0.001 | 0.055 ± 0.04 | 0.061 ± 0.009 | 0.059 ± 0.005 |

| QTc (s) | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 0.044 ± 0.003 | 0.042 ± 0.06 | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.042 ± 0.007 |

| P amplitude (mV) | 0.081 ± 0.003 | 0.089 ± 0.001 | 0.079 ± 0.07 | 0.068 ± 0.003 | 0.0179 ± 0.009 |

| R amplitude (mV) | 0.763 ± 0.02 | 0.642 ± 0.03 | 0.889 ± 0.04* | 0.656 ± 0.002 | 0.875 ± 0.01* |

| S amplitude (mV) | −0.432 ± 0.03 | −0.407 ± 0.04 | −0.3198 ± 0.05 | −0.368 ± 0.05 | −0.385 ± 0.02 |

| ST height (mV) | 0.108 ± 0.02 | 0.101 ± 0.04 | 0.020 ± 0.02 | 0.065 ± 0.02 | 0.075 ± 0.03 |

| T amplitude (mV) | 0.154 ± 0.01 | 0.139 ± 0.03 | 0.145 ± 0.06 | 0.093 ± 0.04 | 0.131 ± 0.03 |

These parameters were recorded from individual rats before treatment (baseline) and after treatment with a single daily dose (treatment period 1) and twice daily doses (treatment period 2) of 3.5% (w/v) minoxidil formulations. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n ≥ 4000 time points, ECG recording). Data significantly different vs baseline *(Student t test, P < .05) (rats per group = 2).

The topical application of single (SF rat vs human = 155) and twice daily doses (SF rat vs human = 311) showed that the novel MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation at a 3.5% concentration (w/v) had a better profile in terms of changes in arterial blood pressure, HR, and electrophysiological action potential parameters, as evaluated by the telemetry monitoring of these parameters in free‐moving rats.

3.5. Pharmacovigilance investigation of cancer, tumor, and neoplasm associated with the use of topical MXD for the treatment of alopecia in the EudraVigilance database from 2014 to 2018

Renal cancer was one of the most serious and unexpected effects observed in rats. We also investigated the association between MXD treatment and cancer in humans. We found 32 spontaneous reports (individual case safety reports) in humans of whom 15 were cases of breast cancer, 7 of skin cancer, and 1 of each prostate, colon, and hepatic cancers, as well as 4 benign neoplasms and other unknown conditions. In 18 cases, the safety action of the clinician was drug withdrawal. Of the 32 patients, 22 were female and 10 male, and 7 patients were >65 while the others were adults. In most of the individual case safety reports no concomitant drugs were reported. http://www.adrreports.eu/it/index.html

4. DISCUSSION

In this work, we investigated the toxicological effects of two different MXD formulations: one mimicking the commonly used MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and a second which is a novel MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation. In our previous experiments, these formulations appeared to be equally effective in improving hair growth in male rats with advantage, in terms of better hair quality, lower in vitro cytotoxicity, and fewer local dermal reactions, in favor of the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation.41

In the repeated escalating doses of MXD (0.035%‐3.5% w/v‐w) experiment, the rats treated once daily with either of the MXD formulations at concentrations of 0.035% (0.0777 g/kg/day), 0.07% (0.1555 g/kg/day), and 3.5% (w/v‐w) (7.777 g/kg/day) experienced mild and insignificant reductions in their arterial blood pressure with no change in HR, shown by telemetry monitoring in free‐moving rats. The cumulative dose of MXD which the experimental groups received using this protocol was 71.15 g/kg.

However, the echocardiographical, morphological, and functional analyses performed at the end of the treatment period showed a significant enhancement of systolic and diastolic left ventricle diameter, systolic and diastolic left ventricle volume, stroke volume, left ventricle mass, and systolic and diastolic left ventricle internal diameter in the rats treated with either of the MXD formulations; the rats treated with the MXD ethanolic formulation were more severely affected.

The post mortem tissues of the MXD‐treated animals showed abnormalities in several organs, as demonstrated by the histopathological and biochemical analyses, and the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution‐treated rats were more severely affected. Additionally, we found cancerous cells positive for Ki‐67 in the kidney tissue sections. A previous dermal study in mice showed an increased incidence of mammary adenomas and adenocarcinomas in females at all dose levels (8, 25, and 80 mg/kg/day), which was attributed to increased serum prolactin (Product monograph ROGAINE®, 2017). Similarly, in rats there were significant increases in the incidence of pheochromocytomas in both genders and of preputial gland adenomas in males, as well as an increase in prolactin secretion, following treatment with topical MXD for 90 days.

KATP channels are composed of an assembly of sulfonylureas receptor subunits (SUR1 and SUR2A/B) and inwardly rectifying potassium channels subunits in different tissues (Kir6.1 and Kir6.2), including skin cells.18, 41, 52, 53 KATP channels and calcium‐activated potassium channels couple the nucleotide and intracellular calcium transient levels with the electrical properties of the cells regulating cell cycling and proliferation.53, 54 KATP‐channel openers, including MXD, induce cell growth in the muscles and dermal tissues, while the downregulation or pharmacological blockage of these channels induces caspase‐3‐dependent atrophy.44, 45, 53, 54, 55, 56

Hypertrophic signaling and cell proliferation are associated with the activation of KATP channels in different tissues. From a pathogenic point of view, the abnormal activation of KATP channels in human glioma cell lines has previously been reported.46 The upregulation of the Kir6.2 subunit, the pore‐forming subunit of the KATP channels, has been associated with cervical cancer in human biopsies.57 Several features of Cantù Syndrome, including cardiac hypertrophy and hypotension, suggest that the effects of MXD in humans and animals are a pharmacological model of this disease.58

In our pharmacovigilance investigation using the EudraVigilance database, we detected 32 cases of cancer, neoplasm, and tumor in different organs, associated with the use of topical MXD. Pre‐existing undiagnosed cancer in the patients using topical MXD cannot be excluded as a possible causative factor in the reports from the EudraVigilance database. Despite MXD not being mutagenic, the activation of KATP channels may induce cell proliferation, promoting tumor growth with drug‐disease interactions. Two signaling pathways have been associated with MXD proliferative action: the AKT pathway, which is involved in hair growth and is oncogenic in cancers; and the ERK pathway, which is oncogenic in skin cancer and hypertrophic in cardiac ventricles.59

Additional experiments were performed to evaluate the effects of high doses of the two MXD formulations on ECG parameters and arterial blood pressure. The once and twice daily topical application of the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL 3.5% w/v formulation showed a better profile in terms of arterial blood pressure, HR, and electrophysiological action potential parameters. Indeed, the once daily application of the MXD 3.5% formulations (w/v‐w) induced a significant decrease in the QTc interval and depression of the ST segment for both formulations, without affecting the arterial blood pressure or HR. The MXD dose investigated corresponds to 7.777 g/kg/day in a rat of 450 g body weight, which is 155 times higher than the human therapeutic dose for the topical application of MXD solution (0.05 g/kg/day). As expected, the twice daily application of the MXD 3.5% (w/v‐w) formulations, corresponding to 311 times the therapeutic human dose with a cumulative dose of 116.655 g/kg of MXD at the end of treatment periods, caused marked cardiovascular effects. This treatment, other than inducing a significant decrease in the QTc interval and depression of the ST segment with both formulations, also significantly reduced the arterial blood pressure in the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution. The observed enhancement of the T amplitude following the once and twice daily doses of the MXD 3.5% (w/v) ethanol/glycol propylene solution can be related to vehicle effects, as they were not observed in the rats treated with the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation.

In conclusion, histopathological analysis of organs collected at the end of treatment confirmed the severe condition of the rats treated with the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution, showing severely affected kidney, liver, and cardiac muscle tissues. The HP‐β‐CD inclusion complex of the MXD gel reduces the adverse proliferative effects of this drug. HP‐β‐CD alone is reported to exert antiproliferative effects in vitro.40, 41 In male rats, the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation showed improved tolerability and toxicological profiles at a wide range of dosages vs the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution.

However, with over 30 years of usage in a large population worldwide, the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution demonstrates few adverse events. The adverse effects which have been reported in the literature concerning topical MXD formulations are mostly related to the tolerability of the formulation. We should point out that, in our experience, high doses of MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution are necessary to cause cardiovascular and renal adverse effects in rats. Despite no PK data being provided in previous in vitro experiments, the novel formulation released MXD more slowly than the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution and a significant release of 70.80 ± 6.0% was obtained at 24 hour. In ex vivo experiments, the best accumulation in the ear skin of pigs was demonstrated for the MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation, with a value about two‐fold greater than, and significantly different from, the MXD ethanol/glycol propylene solution.40 In addition, in a multicenter trial on 307 subjects treated with topical MXD solution (2% or 5%), a MXD plasma level of 21.7 ng/mL was found, which should not be high enough to cause changes in the pulse rate; nevertheless, this effect was observed in patients, suggesting that the plasma concentration of MXD cannot be considered as an indicator of systemic adverse effects after use of the topical formulation.60 The novel MXD HP‐β‐CD GEL formulation could be appropriate for local treatment avoiding the systemic side effects of MXD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

DT conceived this study, designed the experiments, and wrote this manuscript. FM, NZ, AM, ND, RS, GP, AC, and VL conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. A.L, F.L, SV, MF, and DT contributed the essential reagents, tools, and technique. D.T, SF, and MF supervised this project.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOR

This declaration acknowledges that this study adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigor of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for Design & Analysis, Immunoblotting and Immunochemistry, and Animal Experimentation and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers, and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Fig S4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the University of Bari, Italy (founds ATENEO 2014), the Italian Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR, Italy), the Inter‐University Consortium for Research on the Chemistry of Metal Ions in Biological Systems (CIRCMSB, Bari, Italy), and the Farmalabor srl. Centro Studi e Ricerche “Dr Sergio Fontana 1900‐1982” (Canosa di Puglia, Italy) for support.

Maqoud F, Zizzo N, Mele A, et al. The hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclodextrin‐minoxidil inclusion complex improves the cardiovascular and proliferative adverse effects of minoxidil in male rats: Implications in the treatment of alopecia. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8:e00585 10.1002/prp2.585

Nicola Zizzo and Fatima Maqoud equally contributed to the work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rossi A, Anzalone A, Fortuna MC, et al. Multi‐therapies in androgenetic alopecia: review and clinical experiences. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:424‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sawaya ME, Price VH. Different levels of 5alpha‐reductase type I and II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:296‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suchonwanit P, Srisuwanwattana P, Chalermroj N, Khunkhet S. A randomized, double‐blind controlled study of the efficacy and safety of topical solution of 0.25% finasteride admixed with 3% minoxidil vs. 3% minoxidil solution in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2257‐2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mella JM, Perret MC, Manzotti M, Catalano HN, Guyatt G. Efficacy and safety of finasteride therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1141‐1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khandpur S, Suman M, Reddy BS. Comparative efficacy of various treatment regimens for androgenetic alopecia in men. J Dermatol. 2002;29:489‐498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou Z, Song S, Gao Z, Wu J, Ma J, Cui Y. The efficacy and safety of dutasteride compared with finasteride in treating men with androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:399‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caserini M, Radicioni M, Leuratti C, Annoni O, Palmieri R. A novel finasteride 0.25% topical solution for androgenetic alopecia: pharmacokinetics and effects on plasma androgen levels in healthy male volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;52:842‐849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kozicka K, Lukasik A, Pastuszczak M, Wojas‐Pelc A. Methods of treatment patients with androgenetic alopecia based on reference of Department of Dermatology in Cracow. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2019;46:80‐83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee S, Lee YB, Choe SJ, Lee W‐S. Adverse sexual effects of treatment with finasteride or dutasteride for male androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:12‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Basaria S, Jasuja R, Huang G, et al. Characteristics of men who report persistent sexual symptoms after finasteride use for hair loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:4669‐4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goren A, Naccarato T. Minoxidil in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tricarico D, Barbieri M, Antonio L, Tortorella P, Loiodice F, Camerino DC. Dualistic actions of cromakalim and new potent 2H–1,4‐benzoxazine derivatives on the native skeletal muscle K ATP channel. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:255‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wester RC, Maibach HI, Guy RH, Novak E. Minoxidil stimulates cutaneous blood flow in human balding scalps: pharmacodynamics measured by laser Doppler velocimetry and photopulse plethysmography. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:515‐517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sakita S, Kagoura M, Toyoda M, Morohashi M. The induction by topical minoxidil of increased fenestration in the perifollicular capillary wall. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:294‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi N, Shin S, Song SU, Sung J‐H. Minoxidil promotes hair growth through stimulation of growth factor release from adipose‐derived stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mele A, Camerino GM, Calzolaro S, Cannone M, Conte D, Tricarico D. Dual response of the KATP channels to staurosporine: a novel role of SUR2B, SUR1 and Kir6.2 subunits in the regulation of the atrophy in different skeletal muscle phenotypes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;91:266‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kane GC, Liu XK, Yamada S, Olson TM, Terzic A. Cardiac KATP channels in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:937‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B. Evidence‐based treatments for female pattern hair loss: a summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:995‐1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Faghihi G, Mozafarpoor S, Asilian A, et al. The effectiveness of adding low‐level light therapy to minoxidil 5% solution in the treatment of patients with androgenetic alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:547‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sakr FM, Gado AM, Mohammed HR, Adam ANI. Preparation and evaluation of a multimodal minoxidil microemulsion versus minoxidil alone in the treatment of androgenic alopecia of mixed etiology: a pilot study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:413‐423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanglertsampan C. Efficacy and safety of 3% minoxidil versus combined 3% minoxidil / 0.1% finasteride in male pattern hair loss: a randomized, double‐blind, comparative study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1312‐1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsuboi R, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T, et al. A randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of 1% topical minoxidil solution in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in Japanese women. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:37‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rietschel RL, Duncan SH. Safety and efficacy of topical minoxidil in the management of androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:677‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ranchoff RE, Bergfeld WF. Topical minoxidil reduces blood pressure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:586‐587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leenen FH, Smith DL, Unger WP. Topical minoxidil: cardiac effects in bald man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:481‐485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ocampo‐Garza J, Griggs J, Tosti A. New drugs under investigation for the treatment of alopecias. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:275‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dubrey SW, VanGriethuysen J, Edwards CMB. A hairy fall: syncope resulting from topical application of minoxidil. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:1‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wolff H. Minoxidil: from side effects to therapy. Hautarzt. 2016;67:575‐576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu M, Yu Q, Li Q. Differences in reproductive toxicology between alopecia drugs: an analysis on adverse events among female and male cases. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82074‐82084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rojansky N, Fasouliotis SJ, Ariel I, Nadjari M. Extreme caudal agenesis. Possible drug‐related etiology? J Reprod Med. 2002;47:241‐245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smorlesi C, Caldarella A, Caramelli L, Di Lollo S, Moroni F. Topically applied minoxidil may cause fetal malformation: a case report. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:997‐1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Georgala S, Befon A, Maniatopoulou E, Georgala C. Topical use of minoxidil in children and systemic side effects. Dermatology. 2007;214:101‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmutz J‐L, Barbaud A, Trechot P. Systemic effects of topical minoxidil 2% in children. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135:629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lucky AW, Piacquadio DJ, Ditre CM, et al. A randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil solutions in the treatment of female pattern hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:541‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Dotzert MS, Versteeg SG, Shear NH, Piguet V. Efficacy of non‐surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2112‐2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hillmann K, Bartels NG, Kottner J, Stroux A, Canfield D, Blume‐Peytavi U. A single‐centre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of minoxidil topical foam in frontotemporal and vertex androgenetic alopecia in men. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;28:236‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pereira MN, Schulte HL, Duarte N, et al. Solid effervescent formulations as new approach for topical minoxidil delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;96:411‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lopedota A, Cutrignelli A, Denora N, et al. New ethanol and propylene glycol free gel formulations containing a minoxidil‐methyl‐beta‐cyclodextrin complex as promising tools for alopecia treatment. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015;41:728‐736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lopedota A, Denora N, Laquintana V, et al. Alginate‐based hydrogel containing minoxidil/hydroxypropyl‐beta‐cyclodextrin inclusion complex for topical alopecia treatment. J Pharm Sci. 2018;107:1046‐1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tricarico D, Maqoud F, Curci A, et al. Characterization of minoxidil/hydroxypropyl‐beta‐cyclodextrin inclusion complex in aqueous alginate gel useful for alopecia management: efficacy evaluation in male rat. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;122:146‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cagle LA, Franzi LM, Epstein SE, Kass PH, Last JA, Kenyon NJ. Injectable anesthesia for mice: combined effects of dexmedetomidine, tiletamine‐zolazepam, and butorphanol. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2017;2017:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sgoifo A, Stilli D, Medici D, Gallo P, Aimi B, Musso E. Electrode positioning for reliable telemetry ECG recordings during social stress in unrestrained rats. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1397‐1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han JH, Kwon OS, Chung JH, Cho KH, Eun HC, Kim KH. Effect of minoxidil on proliferation and apoptosis in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicle. J Dermatol Sci 2004;34:91‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tricarico D, Mele A, Camerino GM, et al. The KATP channel is a molecular sensor of atrophy in skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2010;588:773‐784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ru Q, Tian X, Wu YX, Wu RH, Pi MS, Li CY. Voltage‐gated and ATP‐sensitive K+ channels are associated with cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of human glioma. Oncol Rep 2014;31:842‐848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mele A, Fonzino A, Rana F, et al. In vivo longitudinal study of rodent skeletal muscle atrophy using ultrasonography. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mele A, Mantuano P, De Bellis M, et al. A long‐term treatment with taurine prevents cardiac dysfunction in mdx mice. Transl Res. 2019;204:82‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim K, Chini N, Fairchild DG, et al. Evaluation of cardiac toxicity biomarkers in rats from different laboratories. Toxicol Pathol. 2016;44:1072‐1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gibson‐Corley KN, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Principles for valid histopathologic scoring in research. Vet Pathol. 2013;50:1007‐1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zizzo N, Passantino G, D'alessio RM, et al. Thymidine phosphorylase expression and microvascular density correlation analysis in canine mammary tumor: possible prognostic factor in breast cancer. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mele A, Calzolaro S, Cannone G, Cetrone M, Conte D, Tricarico D. Database search of spontaneous reports and pharmacological investigations on the sulfonylureas and glinides‐induced atrophy in skeletal muscle. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2014;2:e00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tricarico D, Selvaggi M, Passantino G, et al. Sensitive potassium channels in the skeletal muscle function: involvement of the KCNJ11(Kir6.2) gene in the determination of mechanical Warner Bratzer shear force. Front Physiol. 2016;7:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Curci A, Mele A, Camerino GM, Dinardo MM, Tricarico D. The large conductance Ca(2+) ‐activated K(+) (BKCa) channel regulates cell proliferation in SH‐SY5Y neuroblastoma cells by activating the staurosporine‐sensitive protein kinases. Front Physiol. 2014;5:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tricarico D, Mele A, Calzolaro S, et al. Emerging role of calcium‐activated potassium channel in the regulation of cell viability following potassium ions challenge in HEK293 cells and pharmacological modulation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mele A, Buttiglione M, Cannone G, Vitiello F, Camerino DC, Tricarico D. Opening/blocking actions of pyruvate kinase antibodies on neuronal and muscular KATP channels. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:401‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vazquez‐Sanchez AY, Hinojosa LM, ParraguirreMartínez S, et al. Expression of KATP channels in human cervical cancer: potential tools for diagnosis and therapy. Oncol Lett 2018;15:6302‐6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang Y, McClenaghan C, Harter TM, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of KATP overactivity in Cantu syndrome. JCI insight. 2018;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mutlak M, Kehat I. Extracellular signal‐regulated kinases 1/2 as regulators of cardiac hypertrophy. Front Pharmacol 2015;6:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Olsen EA, Whiting D, Bergfeld W, et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind clinical trial of a novel formulation of 5% minoxidil topical foam versus placebo in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:767‐774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Fig S4