Abstract

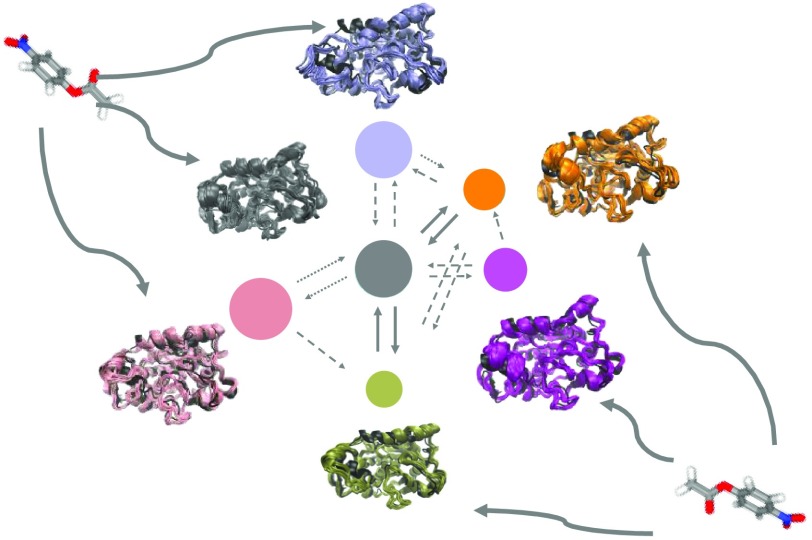

Profiling substrate diffusion pathways with kinetic information, which accounts for the dynamic nature of enzyme–substrate interaction, can enable molecular reengineering of enzymes and process optimization of enzymatic catalysis. Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) is extensively used for producing various chemicals because of its rich catalytic mechanisms, broad substrate spectrum, thermal stability, and tolerance to organic solvents. In this study, an all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) combined with Markov-state models (MSMs) implemented in pyEMMA was proposed to simulate diffusion pathways of 4-nitrophenyl ester (4NPE), a commonly used substrate, from the surface into the active site of CALB. Six important metastable conformations of CALB were identified in the diffusion process, including a closed state. An induced-fit mechanism incorporating multiple pathways with molecular information was proposed, which might find unprecedented applications for the rational design of lipase for green catalysis.

Introduction

Nature offers rich pathways for substrate diffusion toward active sites of enzymes, such as diffusion on the enzyme surface1 and migration through channels,2 tunnels, cavities,3 and so forth. The description of the substrate diffusion process, however, is challenging because, first, atomic-scale enzymatic thermal fluctuation results in the gate opening and closing of the active sites of enzymes. Numerous tunnels are transient, and only certain fluctuations or rearrangements in the enzyme structure make the subsequent travel of ligands possible.4 Second, the multiple substrate interaction is a function of substrate composition and concentration, thus contributing to the aforementioned fluctuations in enzyme conformation. To address this complexity, Plattner and Noé.5 combined molecular dynamics (MD) with Markov-state models (MSMs) and studied the binding kinetics for serine protease trypsin and its inhibitor benzamidine, which exhibited features of both the conformational selection and induced-fit binding models. Ahalawat and Mondal.6 also applied this strategy to probe the substrate recognition pathway of P450cam and showed that the metabolizing camphor needed a substrate-induced side-chain displacement coupled with a complex array of dynamic interconversions of multiple metastable substrate conformations. Kidera et al.7 applied multiscale simulation with enhanced sampling and showed the dominant pathway of glutamine, which was coupled with the conformational changes in the glutamine-binding protein.

Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) is one of the most extensively applied enzymes for chemical production because of its multiple catalytic mechanisms and high tolerance to temperature and organic solvents.8−10 CALB is a globular α/β-type protein with 317 amino acid residues.11 The central β-sheet is composed of seven strands connected by an α helix forming a β–α–β motif. The catalytic triad is composed of SER105, Asp187, and His224, where helices α5, α6, and α10 make up most of the active site pocket for interfacial activation and substrate specificity. Significant efforts from molecular dynamics simulation have been made to elucidate interfacial activation,12−14 catalytic mechanism,18 and enzyme immobilization.17 However, little is known about the substrate diffusion process toward the active site of CALB. Moreover, conformational transitions of CALB during substrate diffusion have never been addressed, particularly at an atomic level.

The present study targeted at the global and kinetic diffusion profile of 4-nitrophenyl ester (4NPE) as the substrate toward the active site of CALB. An all-atom MD simulation with 800 ns was conducted using 40 initial ligand–protein combinations as initial conformations. By combining with MSMs, MD simulations with an overlap in phase space were connected to each other, extending the original timescale to ∼10 μs. Six important metastable conformations of CALB during the 4NPE diffusion process were identified. The diffusion dynamics exhibited an induced-fit mechanism with multiple pathways. The closed state of CALB was identified as being mainly controlled by helix α10. This finding was different from previous observations.12,15,16 These results demonstrated the feasibility of the MD-MSM strategy for simulating enzymatic catalysis in a dynamic manner.

Results and Discussion

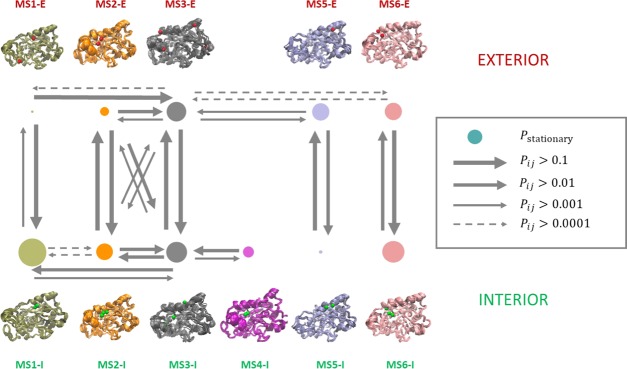

Six Key Metastable States

In this study, six metastable conformations were identified and denoted as MS1, MS2, MS3, MS4, MS5, and MS6. The sampling density plots are shown in Figure S3b. These six states distinguished only the conformational difference but did not differentiate the status of the substrate 4NPE. The obtained microstates from MSM were further split into interior and exterior states according to the distance between SER105 hydroxy oxygen atom and 4NPE ester bond oxygen, as described in the Methods section. This procedure yielded six interior metastable states (denoted as MS1-I, MS2-I, MS3-I, MS4-I, MS5-I, and MS6-I) and five exterior metastable states (MS1-E, MS2-E, MS3-E, MS5-E, and MS6-E).

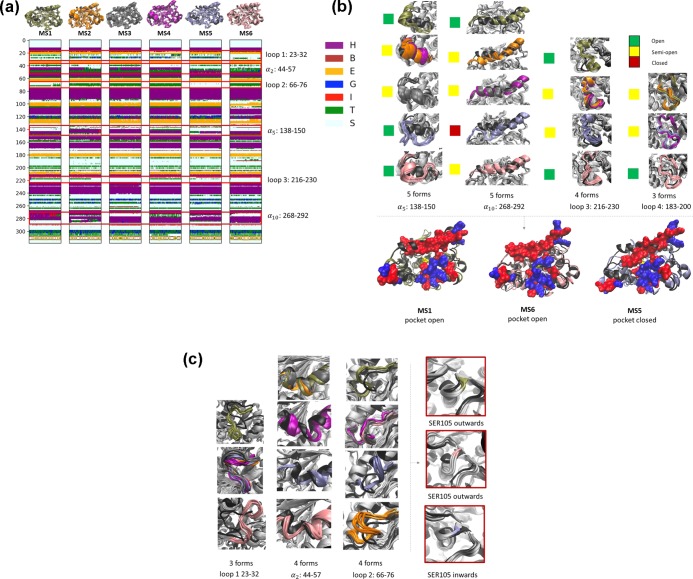

Figure 1a shows the secondary structure analysis of each conformation using the algorithm Define Secondary Structure of Proteins.17 CALB was of great flexibility, especially α5, α10, and loops between the α-helix and β-sheet, as also reported by previous studies.12,18−21 The main differences in the structure of these six conformations were α5 (residues 138–150), α10 (residues 268–292), α2 (residues 44–57), loop 1 (residues 23–32), loop 2 (residues 66–76), and loop 3 (residues 216–230). The partial three-helix property of the loop 1 region disappeared in MS1 and MS6, forming different arrangements of a hydrogen-bonded turn compared to those of MS3 whose structure was the same as the crystal structure of CALB (PDB: 1tca). The α-helix of α2 unwound in MS2, MS5, and MS6. The hydrogen-bonded turn partially disappeared in MS1 and completely disappeared in MS5. The α-helix of α2 partially unwound and showed different patterns in MS1, MS4, MS5, and MS6. The loop 3 of MS1, MS2, MS4, and MS5 partially changed into the hydrogen-bonded turn. Last but not least, α10 revealed the most complicated pattern in the secondary structure. The α10 of MS3, MS1, MS2, and MS5 partially unwound at the terminal (residues 280–292), whereas the α-helix component expanded at the beginning (residues 268–275). Hydrogen-bonded turns were also present among α helix structures in MS2, MS4, and MS5.

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of secondary structures of CALB in different states. In the upper cartoon representation, MS1, MS2, MS3, MS4, MS5, and MS6 are shown in tan, orange, gray, purple, ice blue, and pink, respectively. All of the structures are overlayed with the CALB crystal structure shown in black (PDB: 1tca). (b) Conformational features of α5 (residues 138–150), α10 (residues 268–292), loop 3 (residues 216–230), and loop 4 (residues 183–200). α5 showed five different conformations, of which α10, loop 1, and loop 2 had five, four, and three forms, respectively. The colored squares beside each form of these parts indicate their open (green), semiopen (yellow), and closed (red) states. The hydrophobic pocket of MS1 and MS6 is open, while that of MS5 is closed. (c) Conformational features of loop 1 (residues 23–32), α2 (residues 44–57), and loop 2 (residues 66–76). Loop 1 had three, α2 had four, and loop 2 had four different forms. These three parts controlled the orientation of SER105. The SER105 of MS1 and MS6 bent outward, while that of MS5 bent inward.

Figure 1b shows different structures of α5, α10, loop 3, and loop 4 in six key metastable states. According to the orientation of the deviation from the crystal structure, the structures were classified as close (condensing the pocket size), semiopen (partially expanding the pocket size), and open (expanding the pocket size) states. The structure of MS3 was the same as the crystal structure of CALB. The other states exhibited different conformational features as shown in the secondary structure analysis (Figure 1a). The α5 of MS1, MS5, and MS6 unwound its α-helix structure with three different open conformations. The α5 of MS2, MS4, and MS3 was semiopen, which was similar to the crystal structure. The α10 was open in MS1 and semiopen in other states except MS5, where the α10 structure was closed. The α5, α10, loop 1, and loop 2 of the CALB controlled its pocket size according to different combinations of these conformations. The open or semiopen forms of these four parts resulted in an open pocket just like MS1 and MS6. However, the closed α10 resulted in a closed pocket even if its other parts were open. The dynamic characteristics of these structures affected substrate diffusion, as detailed later.

The other three loops were also significantly different from each other (Figure 1c). Loop 1, α2, and loop 2 had three, four, and four different conformations, respectively. The loop 1 of MS1 and the loop 1 of MS6 had opposite orientations. Similarly, the loop 2 of MS5 and the loop 2 of MS2 also showed opposite orientations. Other conformations of these loops were slightly twisted from the crystal structure. It should be emphasized here that although these three parts (loop 1, α2, and loop 2) were away from the active site, they played key roles in adjusting the orientation of SER105 by pressing or releasing β4, which contained SER105 in it. The SER105 of MS1 and MS6 showed outward orientation, while the SER105 of MS5 bent inward, as shown in Figure 1c.

In addition to MS3 having the same structure as the crystal structure of CALB (PDB: 1tca), the aforementioned metastable states agreed well with published reports. MS6 and MS2 captured in the present study were identified by Luan and Zhou.21 as the two most probable structures after their MD simulations at a timescale of 3.3 μs. MS3 and MS2 also reproduced the “open” and “closed” states of CALB, described by Ganjalikhany et al.16 Moreover, the present study was novel in identifying three brand new structures, including MS1, MS4, and MS5, which play important roles in CALB–4NPE interaction. Among them, MS5 was identified as a closed state of CALB when it interacts with the substrate 4NPE. These three new structures provided a better understanding of the substrate diffusion dynamics and catalytic mechanism.

Conformational Transitions of CALB during Substrate Diffusion

As mentioned previously, the substrate 4NPE appeared in the interior and exterior of five of the six conformations of CALB. This study analyzed the conformational transitions and affinity to substrates, as shown in Figure 2. The overall free energy of diffusion ΔG was calculated from the stationary πι model obtained from the MSM transition matrix, as detailed in the Methods section. The area of the disk represents the equilibrium distribution of metastable states, and the thickness of arrows shows the transition probability among these states.

Figure 2.

Conformational transition network of the six metastable states. The area of the disk is proportional to the equilibrium distribution of the respective conformation. The thickness and style of the arrows represent the magnitude of transition probability between different states. The green, yellow, and red rectangles represent open, semiopen, and closed states identified by the status of α5 and α10, respectively.

Figure 2 shows that these six metastable states of CALB had different substrate affinities. The free energies of diffusion ΔG were −6.2, −1.3, and −0.7 kJ/mol for MS1, MS2, and MS6, respectively, indicating that these conformations favored the interior state of the substrate. MS3 and MS5 had ΔG of 0.01 and 4.4 kJ/mol, respectively, indicating that they were unfavorable for 4NPE diffusion. In addition, MS4 only had a substrate-binding state and could change to MS3 and MS2. Further analysis of the state of α5 and α10 showed that the free energy of binding was related mainly to the open and closed states of α10 but less affected by those of α5. This suggested that the open state of α10 was vital for the CALB to capture the substrate into its active site. These results supported the assumption on the function of α5 and α10 described previously.11,22

MS3 played a vital role in the conformational transition during the dynamic binding process. It was referred to as a transition hub state, which was introduced by Bowman and Pande.23 for the first time. The binding free energy of MS3 to 4NPE was near zero, indicating that the interior and exterior states had almost equal probability. Therefore, MS3 was a bridge to connect different metastable states because both α10 and α5 of this state were semiopen.

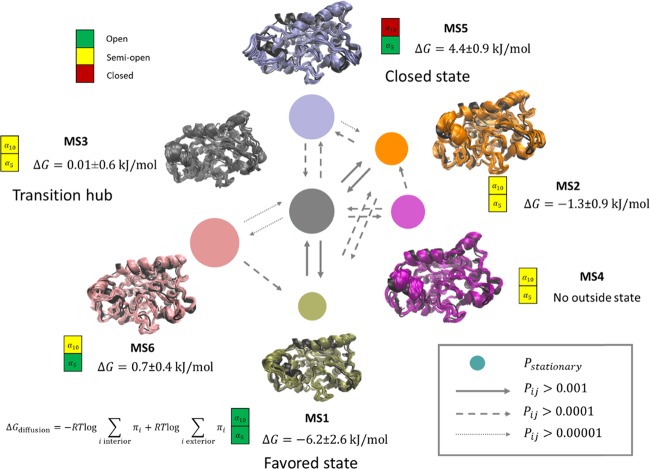

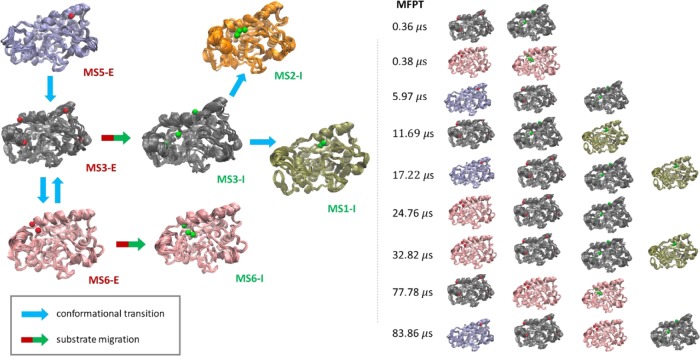

Induced-Fit Mechanism with Multiple Pathways

A global kinetic induced-fit mechanism was proposed (Figure 3) using the aforementioned simulations for the diffusion of 4NPE to the active site of CALB. The most stable exterior states were MS3-E, MS5-E, and MS6-E. The most stable interior states were MS1-I, MS3-I, and MS6-I. The cluster centers of 4NPE for each conformation were shown in the conformational structure. The red sphere stands for centers in exterior states, and the green ones stand for centers in interior states. For all of the metastable states, the interior centers of 4NPE were located at the bottom of the pocket near the active site. Nevertheless, the centers of 4NPE in exterior states were on the surface of CALB and had many possibilities to migrate into the active site. For MS1, the exterior centers were located in the unwound part of α5 and the middle part of α10. For MS2 and MS6, the exterior centers were located in the middle between α5 and α10, which were also accessible for MS3. Further, MS3 had other three exterior centers in the terminal part of α5, close to the terminal part of α10 and the right side of loop 2. As for MS5, the exterior center of 4NPE was located near the right part of α10 above loop 1.

Figure 3.

Kinetic network of diffusion dynamics. The red and green spheres on each conformation are the cluster centers of the substrate 4NPE for exterior and interior states, respectively.

CALB underwent conformational transitions in both exterior and interior states. It could transit to other states because both the exterior and interior states of MS3 were metastable. This explained why gray state acted as a transition hub state. 4NPE separately diffused inside CALB along the tunnel and cavity of each conformation. When a 4NPE in stable exterior state diffused into CALB, a conformation transition occurred simultaneously. The diffusion proceeded, accompanied by CALB conformation transition. This could be described as an induced-fit mechanism.

Diffusion Pathways with Different Timescales

Applying the transition path theory (TPT) analysis implemented in PyEMMA, the dominant diffusion pathways from stable exterior states (MS5-E, MS3-E, and MS6-E) to stable interior states (MS1-I, MS3-I, and MS6-I) were calculated. The detailed pathways are shown in Figure S4, which also shows the pathway fluxes. As shown in Figure 4, the fastest pathway started from MS5-E and ended at MS3-I, with a mean first passage time of 0.36 μs. It is noteworthy that, except direct diffusion from MS6-E to MS6-I, all of the diffusion processes were achieved by MS3 from exterior to interior, indicating the existence of this central state again. The average timescale of the diffusion process was about tens of microseconds. The conformational transition from low-affinity MS5 (ΔG = 4.4 kJ/mol) to moderate-affinity MS3 (ΔG = 0.01 kJ/mol) reduced the energy barrier of whole diffusion.

Figure 4.

Dominant diffusion pathway from stable exterior states (MS5-E, MS3-E, and MS6-E) to stable interior states (MS1-I, MS3-I, and MS6-I) obtained from the TPT analysis implemented in PyEMMA.

MS4 was assigned as a misbound structure because it had only an interior state, and the equilibrium distribution was smaller (0.032) compared to other interior states. The present study investigated rediffusion from MS4-I to the most stable states. The results in Figure 5 show that preferable pathways were MS4-I > MS3-I > MS2-I, MS4-I > MS3-I > MS1-I and MS4-I > MS3-I > MS3-E > MS6-I > MS6-E.

Figure 5.

Rediffusion pathway from the MS4 interior to stable interior states (MS1-I, MS3-I, and MS6-I) obtained from the TPT analysis implemented in PyEMMA.

Conclusions

In this study, the molecular dynamics simulation was combined with MSM to simulate the substrate diffusion kinetics into CALB, taking the CALB conformation transition into consideration. The application of MSM yielded a global and kinetic profile of substrate diffusion into CALB with hundred nanoseconds to tens of microseconds from 800 ns of molecular dynamics simulation. Six metastable states of CALB were identified, including those experimentally observed ones reported in published reports. This was the first study in which the closed state of CALB was captured and was controlled by α10. The conformational transition of CALB was displaced during 4NPE transport, suggesting an induced-fit mechanism of diffusion. MS3 acted as the hub of substrate 4NPE diffusion along nine dominant diffusion pathways. The established global and kinetic profile, generated from an atomic-level MD simulation, was helpful for reengineering enzyme molecules for a given enzymatic catalysis.

Methods

Models

The input model was based on the crystallographic structure of C. antarctica lipase B (PDB ID: 1tca) and the ligand structure of 4-nitrophenyl acetate on Automated Topology Builder Web server24 (https://atb.uq.edu.au/). The Gromos 54a7 force field was applied to both CALB and substrate. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed on the GROMACS package (version 5.1.4). Forty different initial structures with different substrate positions outside the active sites of CALB were randomly generated. All of these complexes were then solvated with 10 173 SPC/E water molecules. The simulation system was neutralized by adding one Na+ ion. The simulation systems contained 33 470 atoms in a simulation box of initial dimensions 72 × 67 × 73 Å3.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Each system was energy-minimized and equilibrated under NVT conditions at 300 K for 100 ps. Then, the system was further equilibrated under NPT conditions at 1 atm and 300 K for 100 ps. During energy minimization until the maximum force was less than 1000.0 kJ/(mol·nm) and equilibration, the heavy protein atoms were restrained by 1 kcal/(mol·Å2) spring constant. Subsequently, the volume was allowed to relax for 20 ns under NPT conditions for each initial structure. Finally, 800 ns MD data were collected.

Markov-State Model

The MSM was performed using the MD simulation data by combining functionalities of the program PyEMMA25 (http://pyemma.org). The minimum distance between the adjacent two residues separated by one residue was input as a feature with a dimension of 315. The slow linear subspace of these input coordinates was then estimated by computing a time-lagged independent component analysis (TICA), and a dimension reduction was achieved by projecting on the five slowest TICA components. The K means clustering algorithm was used to obtain 200 initial microstates. Further, these microstates were split into interior and exterior states based on the distance between the SER105 hydroxy oxygen atom and ester bond oxygen of the substrate with a cutoff of 14 Å. This yielded a new set of 372 microstates. The cutoff was determined on the basis of the frequency statistics of the SER105–substrate distance of all trajectories (Figure S1). The transition matrix was calculated using the maximum likelihood reversible transition matrix with the quadratic optimizer implemented in the PyEMMA package.

The Markov model was validated in two steps. First, the implied timescales were calculated as a function of the lag time τ. Moving block bootstrapping with block size τ was employed to calculate statistical uncertainties. Figure S2b shows the expectation value and the 1σ confidence interval of τ-dependent timescales. Timescales became constant within the statistical error at a lag time of 15–25 time steps (dt = 0.01 ns). Here, t = 0.2 ns was chosen to estimate the final MSM. Second, a Chapman–Kolmogorov test of MSM implemented in PyEMMA was conducted. The MSM estimated at 0.2 ns was consistent with simulation data at all lag times up to 1 ns (Figure S2c).

Metastable States

The PCCA+ method implemented in PyEMMA was used to capture the metastable sets of microstates. Given that a gap was found after the sixth eigenvalue in Figure S3a, six metastable sets were identified. Because the substrate diffusion was faster compared to the conformational changes in CALB, the metastable states of the substrate could be classified into interior and exterior states, thus resulting in five exterior metastable states and six interior metastable states.

Calculation of Gibbs Free Energy of Diffusion

For each metastable set of microstates, the overall free energy of diffusion was computed based on the stationary probability πι of the interior and exterior states.

| 1 |

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2018YFA0902200 and the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation under Grant No. 21878175.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04432.

Frequency statistics of the distance between SER105 hydroxy oxygen atom and 4NPE ester bond oxygen atom of all trajectories (Figure S1); K means clusters on the free-energy landscape and the validation of the constructed MSM (Figure S2); eigenvalues from large to small of the Markov-state model transition matrix and the sampling density plots of the six metastable states identified using the PCCA+ algorithm (Figure S3); and transition pathway theory analysis of the diffusion pathways from the stable exterior states to the stable interior states (Figure S4) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nerukh D.; Okimoto N.; Suenaga A.; Taiji M. Ligand diffusion on protein surface observed in molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 3476–3479. 10.1021/jz301635h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einolghozati A.; Sardari M.; Fekri F. In Capacity of Diffusion-Based Molecular Communication with Ligand Receptors, 2011 IEEE Information Theory Workshop, IEEE, 2011; pp 85–89.

- Gora A.; Brezovsky J.; Damborsky J. Gates of enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5871–5923. 10.1021/cr300384w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzewski J.; Nowak W. Ligand diffusion in proteins via enhanced sampling in molecular dynamics. Phys. Life Rev. 2017, 22–23, 58–74. 10.1016/j.plrev.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner N.; Noé F. Protein conformational plasticity and complex ligand-binding kinetics explored by atomistic simulations and markov models. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7653 10.1038/ncomms8653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahalawat N.; Mondal J. Mapping the substrate recognition pathway in cytochrome p450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17743–17752. 10.1021/jacs.8b10840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritsugu K.; Terada T.; Kidera A. Free-energy landscape of protein-ligand interactions coupled with protein structural changes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 731–740. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b11696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. M.; Larsson K. M.; Kirk O. One biocatalyst–many applications: the use of candida antarctica b-lipase in organic synthesis. Biocatal. Biotransform. 1998, 16, 181–204. 10.3109/10242429809003198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gotor-Fernández V.; Busto E.; Gotor V. Candida antarctica lipase b: an ideal biocatalyst for the preparation of nitrogenated organic compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 797–812. 10.1002/adsc.200606057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Hu J.; Miller E. M.; Xie W.; Cai M.; Gross R. A. Candida antarctica lipase b chemically immobilized on epoxy-activated micro- and nanobeads: catalysts for polyester synthesis. Biomacromolecules 2008, 463–471. 10.1021/bm700949x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppenberg J.; Hansen M. T.; Patkar S.; Jones T. A. The sequence, crystal structure determination and refinement of two crystal forms of lipase b from candida antarctica. Structure 1994, 2, 293–308. 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisis T.; Freddolino P. L.; Turunen P.; Van Teeseling M. C. F.; Rowan A. E.; Blank K. G. Interfacial activation of candida antarctica lipase b: combined evidence from experiment and simulation. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5969–5979. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.; Soni P.; Reetz M. T. Laboratory evolution of enantiocomplementary candida antarctica lipase b mutants with broad substrate scope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1872–1881. 10.1021/ja310455t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum I.; Elsässer B.; Schwab L. W.; Loos K.; Fels G. Atomistic model for the polyamide formation from β-lactam catalyzed by Candida antarctica lipase b. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 323–336. 10.1021/cs1000398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stauch B.; Fisher S. J.; Cianci M. Open and closed states of Candida antarctica lipase b: protonation and the mechanism of interfacial activation. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 2348–2358. 10.1194/jlr.M063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganjalikhany M. R.; Ranjbar B.; Taghavi A. H.; Tohidi Moghadam T. Functional motions of candida antarctica lipase b: a survey through open-close conformations. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40327 10.1371/journal.pone.0040327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poh S. C.; Chew S. E. Routine follow up of patients with treated pulmonary tuberculosis. Singapore Med. J. 1975, 16, 200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber C. C.; Pleiss J. Lipase b from candida antarctica binds to hydrophobic substrate-water interfaces via hydrophobic anchors surrounding the active site entrance. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2012, 84, 48–54. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2012.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan J.; Kothai T.; Lakshmi B. S. In silico approaches towards understanding calb using molecular dynamics simulation and docking. Mol. Simul. 2011, 37, 1053–1061. 10.1080/08927022.2011.589050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryde U.; Larsen M. W.; Genheden S.; Hatti-Kaul R.; Irani M.; Törnvall U. Amino acid oxidation of candida antarctica lipase b studied by molecular dynamics simulations and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1280–1289. 10.1021/bi301298m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan B.; Zhou R. A novel self-activation mechanism of: candida antarctica lipase b. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 15709–15714. 10.1039/C7CP02198D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjøt M.; de Maria L.; Chatterjee R.; Svendsen A.; Patkar S. A.; Østergaard P. R.; Brask J. Understanding the plasticity of the α/β hydrolase fold: lid swapping on the candida antarctica lipase b results in chimeras with interesting biocatalytic properties. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 520–527. 10.1002/cbic.200800668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman G. R.; Pande V. S. Protein folded states are kinetic hubs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 10890–10895. 10.1073/pnas.1003962107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziara K. B.; Stroet M.; Malde A. K.; Mark A. E. Testing and validation of the automated topology builder (atb) version 2.0: prediction of hydration free enthalpies. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2014, 28, 221–233. 10.1007/s10822-014-9713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer M. K.; Trendelkamp-Schroer B.; Paul F.; Pérez-Hernández G.; Hoffmann M.; Plattner N.; Wehmeyer C.; Prinz J. H.; Noé F. PyEMMA 2: a software package for estimation, validation, and analysis of markov models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 5525–5542. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.