Abstract

In this study, a siderophore, pyoverdine (PVD), has been isolated from Pseudomonas sp. and used to develop a fluorescence quenching-based sensor for efficient detection of nitrotriazolone (NTO) in aqueous media, in contrast to other explosives such as research department explosive (RDX), picric acid, and trinitrotoulene (TNT). The siderophore PVD exhibited enhanced fluorescence quenching above 50% at 470 nm for a minimal concentration (38 nM) of NTO. The limit of detection estimated from interpolating the graph of fluorescence intensity (at 470 nm) versus NTO concentration is found to be 12 nM corresponding to 18% quenching. The time delay fluorescence spectroscopy of the PVD–NTO solution showed a negligible change of 0.09 ns between the minimum and maximum NTO concentrations. The in silico absorption at the emission peak of static fluorescence remains invariant upon the addition of NTO. The computational studies revealed the formation of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions between the energetically stable complexes of PVD and NTO. Although the analysis of Stern–Volmer plots and computational studies imply that the quenching mechanism is a combination of both dynamic and static quenching, the latter is dominant over the earlier. The static quenching is attributed to ground-state complex formation, as supported by the computational analysis.

Introduction

The increase in activities of terrorists and militants threatening homeland security and public safety has led to accelerating growth of research in the field of explosive detection.1 The stand-off detection of explosives is highly difficult due to their very low vapor pressures at normal temperature and pressure. To elucidate, one of the commonly used explosives trinitrotoulene (TNT) has a vapor pressure of 1.1 × 10–6 torr, followed by its precursor dinitrotoluene (DNT) exhibiting a vapor pressure higher by 2 orders of magnitude.2,3 Furthermore, nitramines such as research department explosive (RDX), high melting explosive (HMX), and nitrotriazolone (NTO) have much lower vapor pressures and necessitate the parts per trillion level of sensitivity for stand-off detection.3 The stand-off detection or remote sensing of explosives is mostly carried out using chemoresistive sensing and fluorescence quenching methods. In this context, a variety of metal oxides (undoped and doped) and their nanostructures have been investigated.4−8 Similarly, studies on explosive sensing due to fluorescence quenching of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and various polymers (functionalized with inorganic and/or organic species) have been reported by various researchers.9−13

Recently, Sun et al. have presented a brief review of fluorescence-based explosive detection.3 Notably, a unique and arguably best sensing level is reported by peptide-modulated single-walled CNT fluorescence quenching of nitramines.14 Furthermore, owing to very low vapor pressures, some of the researchers have attempted explosive detection via sensing of NO and/or NO2 vapors generated due to the disintegration of the parent species.15,16

In recent years, due to the problems associated with handling, transportation, sympathetic detonation, and dimensional instability at elevated temperatures, the common explosives are less attractive. In this context, 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) has emerged as a vital explosive molecule possessing high performance (close to that of RDX), good thermal stability, and insensitivity comparable to those of 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene (TATB). Due to the self-binding property of NTO, it is relatively easy to make its pressable and castable charges.17 In addition, NTO is found to be better than RDX in terms of impact, thermal, and electrostatic discharge sensitivity.18 The above properties make NTO an explosive of choice; however, its practical use is observed to be very limited, as compared to that of other explosives. In most of the field applications, TNT and RDX are used, as revealed from the reports. Due to enhanced properties, it is expected that NTO may be used in field applications in the near future. Guo et al. have used 4,4′-((Z,Z)-1,4-diphenylbuta-1,3-diene-1,4-diyl)dibenzoic acid (TABD) metal–organic framework with Co2+ to detect NTO by a fluorescence turn-on mechanism down to 6.5 ng limit.19 Sensing of explosives in water has gained importance in view of the detection of buried explosives in the form of landmines or next-generation explosives devices, termed as improvised explosive devices. Since most of the explosives have low reactivity and solubility in water, their detection in aqueous media is a challenging task. In recent years, siderophore fluorescence quenching-based biosensors have attracted a great deal of attention owing to their abundance in nature and improved selectivity and stability. Furthermore, these compounds exhibit structural diversity with the fixed core moiety.20,21 Among the diverse siderophores generated by different bacterial genera, pyoverdine (PVD) is the special class of siderophores. There are a few reports wherein the fluorescence quenching behavior of PVD has been efficiently utilized to detect various organic and inorganic species. Pawar et al. have extracted PVD from soil isolate Pseudomonas monteilii strain MKP 213 and tested its fluorescence quenching for various antibiotics in aqueous solutions.22 Out of these, ciprofloxacin showed very strong and selective quenching. Yin et al. have purified PVD from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA1 using affinity chromatography and reported fluorescence quenching detection of antibiotic furazolidone.23 The authors have proposed that the interaction between the −NO2 group in furazolidone and PVD chromophore via electron transfer is responsible for the observed fluorescence quenching. Following this, we thought that fluorescence quenching of PVD could be tested for the detection of NTO in an aqueous medium, which is hitherto not reported. In the present study, we report selective detection of NTO in aqueous medium using fluorescence quenching of siderophore PVD isolated from Pseudomonas sp. In addition to NTO, fluorescence quenching characteristics for the detection of other explosives like RDX, picric acid, HMX, and TNT were studied to reveal detection selectivity. Furthermore, to reveal the underlying sensing mechanism, computational analysis has been carried out, which implies the formation of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions between the energetically stable complexes of PVD and NTO.

Results and Discussion

Fluorescence Measurements and Related Studies

The initial static fluorescence study of PVD (0.2 mg/mL) has been carried out in the presence of different explosives to reveal the selectivity. The concentration of each explosive was kept as 90 nM, and the fluorescence quenching of each explosive was studied independently.

From Figure 1, it can be seen that the fluorescence of PVD is not affected due to the presence of RDX and picric acid, whereas for TNT and NTO, it showed around 40 and 80% quenching, respectively. Even though all of these compounds have a nitro group, the strong interaction is seen with NTO, followed by TNT. Hence, a detailed investigation is needed to reveal the interaction with PVD. (The UV absorption and static fluorescence graphs for the pure NTO solution (90 nM) are presented in Supporting Information Figure S11a,b, respectively.)

Figure 1.

Fluorescence response of PVD toward the detection of various explosives: (a) pristine PVD without any explosive, (b) picric acid, (c) TNT, (d) RDX, and (e) NTO (λexc = 360 nm, λem = 470 nm, 2.5 μm slit width).

Initially, the qualitative analysis of PVD and NTO interaction was studied by observing the overall fluorescence response of PVD–NTO solutions of different concentrations ranging from 38 to 228 nM, subjected to visible and UV irradiation. It is clearly revealed that, upon visible illumination, no fluorescence is observed and the PVD solutions containing various NTO concentrations exhibited no change in color (Figure 2A). When exposed to broad UV light, the PVD–NTO solutions show a noticeable change in color, depending on the NTO concentration (Figure 2B). This change in color is indicative of the fluorescence quenching response in a qualitative manner.

Figure 2.

Overall fluorescence response of PVD–NTO solutions (with increasing NTO concentrations, left to right) upon illumination with (A) visible light, (B) wide-band UV lamp, (C) UV source ∼265 nm, and (D) UV source ∼365 nm.

To explore the dependence of fluorescence activity on illuminating photons, the PVD–NTO solutions were exposed to short- and long-range UV light (Figure 2C,D). In both cases, fluorescence activity is observed, which exhibits variation with respect to the NTO concentration. Careful observation reveals that upon short-range illumination the change in the fluorescence activity as a function of NTO concentration is significant in contrast to that upon long-range illumination (Figure 2D).

By taking into consideration the above facts, we observe the static fluorescence response of PVD–NTO solutions of different NTO concentrations (Figure 3). This PVD showed fluorescence intensity at 470 nm (the wavelength at which maximum emission is observed). The fluorescence intensity was found to decrease drastically by more than 50% for 38 nM NTO, with respect to that of pristine PVD. With an increase in the NTO concentration, the fluorescence intensity was observed to decrease, and at an NTO concentration of 114 nM, 90% fluorescence quenching was observed.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence response of pyoverdine upon the addition of various concentrations of NTO (at λexc = 360 nm and 2.5 μm slit width).

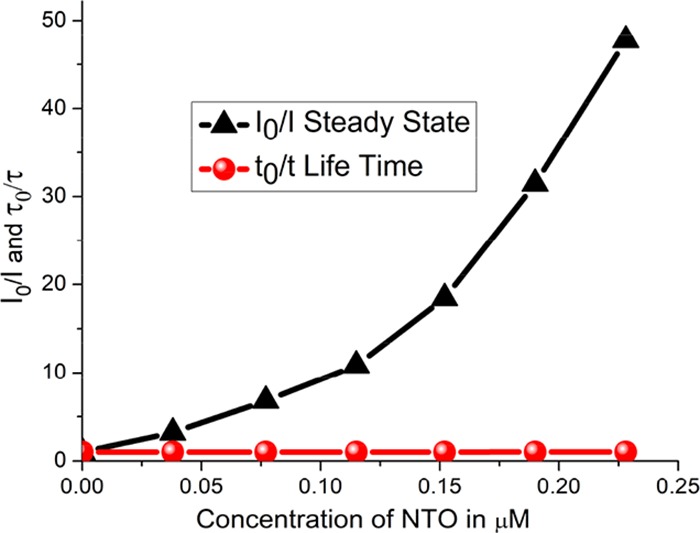

To investigate the quenching mechanism, time-delayed fluorescence spectroscopy was employed. The PVD without NTO showed a delay of 4.44 ns, whereas in the case of 228 nM NTO, the delay was estimated to be 4.35 ns. Time-delayed fluorescence spectra of PVD–NTO solutions showed a negligible change of 0.09 ns between the minimum and maximum NTO concentrations. This shows that fluorescence time delay is nearly the same for both the pristine PVD and NTO–PVD, implying that the fluorescence quenching mechanism is not purely dynamic quenching by resonance energy transfer.3 The observed fluorescence decays were analyzed using DAS-6 software from IBH by an appropriate exponential function. For all of the accepted fits, the χ2 values were close to unity and the weighted residuals were distributed randomly around zero among the data channels. The absorption spectra of PVD–NTO showed a peak at around 320 nm (attributed to the presence of NTO), and no significant change in absorption around 400 nm (characteristic of PVD). Furthermore, to identify whether the fluorescence quenching mechanism is purely static or dynamic in nature, the observed fluorescence response (Figure 3) and time-delayed fluorescence spectroscopic data (Figure 4) were analyzed using Stern–Volmer plots, i.e., plots of I0/I and τ0/τ as a function of NTO concentrations, as depicted in Figure 5. (All other excited-state lifetime data are provided in Supporting Information, Figures S1–S8.)

Figure 4.

Combined S–V plot for steady-state fluorescence and excited-state lifetime plot of pyoverdine with NTO.

Figure 5.

Excited-state lifetime plots with excitation at 374 nm.

Purely dynamic quenching requires changes in the lifetime, τ, with the concentration of the quencher (i.e., NTO in the present case) as well as I0/I = τ0/τ, which are not observed in the present study. Furthermore, for the purely static quenching mechanism, the I0/I versus concentration plot typically showed a linear behavior, expressed as I0/I = 1 + KS·Q, where Q represents the concentration of the quencher and KS is a constant. Interestingly, one of the Stern–Volmer plots, I0/I versus concentration, exhibits upward curving behavior, mathematically expressed as I0/I = 1 + (KD + KS)·Q + KS·KD·Q2. Thus, the Stern–Volmer plots indicate that the quenching mechanism is neither purely dynamic nor purely static.

Also, for dynamic quenching, it is reported that the absorption spectra remain unchanged with changes in the quencher concentration, whereas for static quenching, due to ground-state complex formation, the absorption spectra exhibited change with the quencher concentration (see the Supporting Information, Figure S1). The present study indicates that static quenching, being observed here, plays a dominant role in fluorescence quenching,3 which is supported by the computational study.

Computational Study

The geometrically optimized complex of PVD with NTO has been obtained after the calculations. In this stable complex, the PVD adopted a cavity-like structure in which the NTO molecule was precisely positioned with the help of strong intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions (Figure 6). The hydroxyl groups of the chromophore interact with NTO by forming (Q-Chromo)O1···H–N1(NTO), (Q-Chromo)O2···H–N1(NTO) and (NTO)O1···H–O2(Q-Chromo) H-bonding interactions (Table 1). Similar kinds of interactions were observed between chromophoric groups of PVD and various analytes such as furazolidone, ciprofloxacin, and Fe in fluorescence quenching studies. However, no clear-cut mechanism has been proposed in any of these studies. Herein, we provided for the first time the molecular mechanism of fluorescence quenching with NTO by the computational approach. Thus, the observed hydrogen-bonding pattern in the PVD–NTO complex might be responsible for the quenching of PVD fluorescence by NTO, as observed in experimental studies (Table 1). Shanmugaraju et al. studied the fluorescence quenching of π electron-rich fluorescent supramolecular polymers in the presence of TNT and suggested that static quenching takes place by ground-state complex formation.24

Figure 6.

Molecular interactions from the optimized stable complex of pyoverdine with NTO.

Table 1. Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions from the Optimized Stable Complex of PVD with NTO.

| atoms involved (1–2–3) in H bonds | distance 1–2 (Ǻ) | angle 1–2–3 (°) |

|---|---|---|

| (Q-Chromo)O1···H–N1(NTO) | 2.214 | 125.19 |

| (Q-Chromo)O2···H–N1(NTO) | 1.911 | 114.27 |

| (NTO)O1···H–N(d-Ser) | 2.275 | 143.47 |

| (NTO)O1···H–O2(Q-Chromo) | 1.948 | 113.69 |

| (Lys)O···H–N3(NTO) | 1.868 | 164.19 |

| (NTO)O2···H–N(His) | 2.373 | 114.15 |

| (NTO)O3···H–C(d-Thr) | 1.958 | 178.39 |

| (D-Thr)O···H–N(cOHOrn) | 2.139 | 144.47 |

| (d-Ser)O···H–O1(Q-Chromo) | 1.916 | 156.67 |

| (OHHis)O···H–O(D-Ser) | 1.740 | 163.28 |

| (Q-Chromo)O···H–O(OHHis) | 1.810 | 163.68 |

| (OHHis)N···H–N(Lys) | 2.261 | 141.33 |

| (Lys)N···H–O(Q-Chromo) | 1.627 | 169.94 |

| (d-Ser)O···H–N(Lys) | 2.417 | 155.61 |

Conclusions

The fluorescence quenching behavior of siderophore pyoverdine toward the detection of NTO in the aqueous medium has been studied. The fluorescence quenching was found to be strong and reproducible. The selectivity studies showed that PVD fluorescence quenching was maximum for NTO, followed by TNT and negligible interaction with RDX and picric acid. Enhanced fluorescence quenching of above 50% was observed for the lowest concentration of NTO (38 nM). The proposed mechanism of fluorescence quenching is a combination of both dynamic and static quenching, with static quenching highly dominant and attributed to ground-state complex formation. The computational studies revealed the formation of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions between the energetically stable complexes of PVD and NTO with −2928.25 kJ/mol. Based on the experimental results, supplemented by the computational analysis, we propose the static quenching mechanism via ground-state charge-transfer complex formation between pyoverdine and NTO. This study will open up a new horizon for PVD-based explosive detection in the near future.

Experimental Section

Explosives

The sources and grades of explosives procured/arranged vary. NTO was procured from the Organic Chemistry Department, Savitribai Phule Pune University through HEMRL, while TNT, RDX, and HMX were made by Solar Industries, Nagpur with CAS numbers 118-96-7, 121-82-4, and 2691-41-0, respectively. Picric acid with CAS number 88-89-1 was procured from SD Fine Chemicals, India.

Siderophore Synthesis

The siderophore-producing strain of Pseudomonas taiwanesis R-12-2 was grown in the iron-free modified standard succinate medium (mSM-B) composed of (g/L) succinate, 5.0; NH4Cl, 2.5; K2HPO4, 0.5; KH2PO4, 0.5; and MgSO4·7H2O, 0.9. This is the modified version of media reported by Meyer and Abdallah.25 A flask was incubated at 30 °C, 150 rpm for 48 h. The color of media changed from colorless to fluorescent green, which was due to the production of siderophore pyoverdine by bacteria. The siderophore formation was also confirmed using the universal chrome azurol S (CAS) plate assay by spotting bacterial colonies on the CAS agar plates incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. The CAS agar plate was prepared as mentioned previously.26 For initial screening, the halo zone formation on the CAS plate and green fluorescent compound formation in the SSM indicated the siderophore synthesizing ability of the strain. The siderophore was further characterized by UV spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy.

Production and Partial Purification of Pyoverdine

The strain of Pseudomonas taiwanesis R-12-2 was inoculated into a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of sterilized SSM medium. The flask was incubated for 48 h at 30 °C. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 8000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was further partially purified by initial filtration through a membrane filter (pore size ∼0.22 μm; Amicon) and adsorbed on Sep-Pak RP-C18 cartridges (Waters Millipore, Milford, MA). The column was desalted by washing with 20 mL of water, and then, elution was carried out with 10 mL of methanol–water (70:30, v/v).27 The eluted fractions were lyophilized, and the powder obtained after drying was resuspended in sterile Milli-Q water and used further for NTO sensing studies.

Detection of NTO Using Fluorescence Quenching

The siderophore PVD was prepared in the aqueous medium with a fixed amount of PVD (0.2 mg/mL) at 65 mM concentration. The four different explosives, viz., RDX, TNT, picric acid, and NTO, were used for selectivity study. On the basis of the initial fluorescence quenching study of these four explosives, we have selected NTO as a potential candidate that showed promising results and the following experiments were conducted with NTO alone. The stock solutions of different concentrations of NTO were prepared in distilled water.

The optimization studies were carried out in relation to the concentration of PVD and fluorescence intensity. The amount of PVD (0.2 mg/mL) at 65 mM was used for explosive-specific functionalization study via fluorescence quenching for the detection of lower concentrations of NTO. Different concentrations of NTO ranging from 1 to 300 nM were prepared and tested for their fluorescence quenching. For the fluorescence measurements, an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 470 nm with 2.5 μm slit width were used. The steady-state emission spectra were obtained using a Jasco FP-8300 spectrofluorometer. Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed using a time-correlated single-photon counting instrument (Horiba JobinYvon IBH, U.K.). A 374 nm pulsed diode laser (Nano LED) was used as the excitation source, and the fluorescence decays were collected using a PMT-based detection module.

Computational Studies

To corroborate the experimental results and elucidate the structural details of PVD quenching by NTO, computational studies were performed. The initial geometry of PVD was constructed according to the earlier reported sequence for P. taiwanesis sp.28 The structure of PVD was geometrically optimized using a molecular mechanics force field (MMFF) method. Similarly, the initial geometry of NTO was generated and optimized using ab initio density functional theory employing B3LYP/6-31** basis set.29 The starting complex of PVD and NTO was generated by performing the MMFF energy calculations and subjected to conformer distribution analysis. The 300 steps of conformer distribution calculations were carried out on the PVD–NTO complex using a quantum chemical semiempirical PM6 method.30 The molecular structure generation and optimization calculations were carried out with the help of Spartan’14 (Wavefunction, Inc.) software.31 Similar computational studies have been performed for structural elucidations of fluorinated nucleosides and fluorinated furanoid sugar amino acids and for understanding the mechanism of transmembrane ion transport.32−34 A total of 10 different conformer complexes were obtained, out of which the stable complex of PVD–NTO possessing the lowest energy (−2928.25 kJ/mol) was subjected for full geometry optimization by the ab initio Hartree–Fock (6-31G** basis set) method using Gaussian 16 software.35 The optimized complex of PVD–NTO was analyzed for intramolecular as well as intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr. Nilesh Naik, HEMRL for his vital support in providing NTO and other explosive moieties, the Director of HEMRL for permission to carry out the research work, and Heads of the Department of Physics and Department of Chemistry, SPPU for providing the resources to carry out the research work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NTO

nitrotriazolone

- PVD

pyoverdine

- LED

light-emitting diode

- TNT

trinitrotoulene

- RDX

research department explosive

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03844.

UV–visible absorption spectra of NTO–PVD solutions after adding different quantities of the NTO aqueous solution; excited-state lifetime of pyoverdine aqueous solution and 1 μL of NTO–pyoverdine aqueous solution; Stern–Volmer plot of the NTO–pyoverdine aqueous solution for the excited state and steady state; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of NTO; HPLC and LCMS profiles of pyoverdine; schematic of the molecular structure of pyoverdine; UV–visible absorption and static fluorescence spectra of the NTO aqueous solution; and peak identification for pyoverdine (Figures S1–S11 and Table S1) (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ P.A.K. and V.N. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Steinfeld J. I.; Wormhoudt J. Explosive detection: A challenge for physical chemistry. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1998, 49, 203–232. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.49.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. Sensors—An effective approach for the detection of explosives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 144, 15–28. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X. C.; Wang Y.; Lei Y. Fluorescence based explosive detection: from mechanisms to sensory materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8019–8061. 10.1039/C5CS00496A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. M.; Tian J. Y.; Liu C. S. A luminescent Li(I)-based metal–organic framework showing selective Fe(III) ion and nitro explosive sensing. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2016, 68, 29–32. 10.1016/j.inoche.2016.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gole B.; Bar A. K.; Mukherjee P. S. Fluorescent metal–organic framework for selective sensing of nitroaromatic explosives. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12137–12139. 10.1039/c1cc15594f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L.; Li H. L.; Song M. X.; Dong F. Q.; Zhang X. Y.; Hou W. P. Detection mechanism of perovskite BFO (1 1 1) membrane for FOX-7 and TATB gases: molecular-scale insight into sensing ultratrace explosives. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 105601 10.1088/1361-6463/50/10/105601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan A.; Li K.; Wu H.; Olson D. H.; Emge T. J.; Ki W.; Hong M.; Li J. A Luminescent Microporous Metal–Organic Framework for the Fast and Reversible Detection of High Explosives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2334–2338. 10.1002/anie.200804853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu R.; Liu B.; Wang Z.; Gao D.; Wang F.; Fang Q.; Zhang Z. Amine-Capped ZnS-Mn2+ Nanocrystals for Fluorescence Detection of Trace TNT Explosive. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 3458–3465. 10.1021/ac800060f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Venkatramaiah N.; Patil S. Fluoranthene Based Derivatives for Detection of Trace Explosive Nitroaromatics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7236–7245. 10.1021/jp3121148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daglar B.; Demirel G. B.; Bayindir M. Fluorescent Paper Strips for Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Nitroaromatic Analytes in Water Samples. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 7735–7740. 10.1002/slct.201701352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kartha K. K.; Sandeep A.; Praveen V. K.; Ajayaghosh A. Detection of Nitroaromatic Explosives with Fluorescent Molecular Assemblies and π-Gels. Chem. Rec. 2015, 15, 252–265. 10.1002/tcr.201402063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca D. C.; Pernites R. B.; Del Mundo F. R.; Advincula R. C. Detection of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene (DNT) as a Model System for Nitroaromatic Compounds via Molecularly Imprinted Short-Alkyl-Chain SAMs. Langmuir 2011, 27, 6768–6779. 10.1021/la105128q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyryanov G. V.; Palacios M. A.; Anzenbacher P. Jr. Simple Molecule-Based Fluorescent Sensors for Vapor Detection of TNT. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3681–3684. 10.1021/ol801030u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller D. A.; Pratt G. W.; Zhang J.; Nair N.; Hansborough A. J.; Boghossian A. A.; Reuel N. F.; Barone P. W.; Strano M. S. Peptide secondary structure modulates single-walled carbon nanotube fluorescence as a chaperone sensor for nitroaromatics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 8544–8549. 10.1073/pnas.1005512108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther J. U.; Bohling C.; Mordmueller M.; Schade W. Trace detection of nitrogen-based explosives with UV-PLF. Proc. SPIE 2010, 7838, 783807 10.1117/12.865590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtas J.; Stacewicz T.; Bielecki Z.; Rutecka B.; Medrzycki R.; Mikolajczyk J. Towards optoelectronic detection of explosives. Opto-Electron. Rev. 2013, 21, 9–18. 10.2478/s11772-013-0082-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukundan T.; Purandare G. N.; Nair J. K.; Pansare S. M.; Sinha R. K.; Singh H. Explosive Nitrotriazolone Formulates. Def. Sci. J. 2002, 52, 127–133. 10.14429/dsj.52.2157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spear R. J.; Louey C. N.; Wolfson M. G.. A Preliminary Assessment of NTO as an Insensitive High Explosive, MRL-TR-89-18, Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, 1989; pp 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Feng X.; Han T.; Wang S.; Lin Z.; Dong Y.; Wang B. Tuning the luminescence of metal–organic frameworks for detection of energetic heterocyclic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15485–15488. 10.1021/ja508962m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hider R. C.; Kong X. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 637–657. 10.1039/b906679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cézard C.; Farvacques N.; Sonnet P. Chemistry and Biology of Pyoverdines, Pseudomonas Primary Siderophores. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 165–186. 10.2174/0929867321666141011194624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar M. K.; Tayade K. C.; Sahoo S. K.; Mahulikar P. P.; Kuwar A. S.; Chaudhari B. L. Selective ciprofloxacin antibiotic detection by fluorescent siderophore pyoverdin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 81, 274–279. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin K.; Zhang W.; Chen L. Pyoverdine secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a biological recognition element for the fluorescent detection of furazolidone. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 51, 90–96. 10.1016/j.bios.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaraju S.; Jadhav H.; Karthik R.; Mukherjee P. S. Electron rich supramolecular polymers as fluorescent sensors for nitroaromatics. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 4940–4950. 10.1039/c3ra23269g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. M.; Abdallah M. A. The Fluorescent Pigment of Pseudomonas fluorescens: Biosynthesis, Purification and Physicochemical Properties. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1978, 107, 319–328. 10.1099/00221287-107-2-319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B.; Neilands J. B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 160, 47–56. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilz S.; Lenz C.; Fuchs R.; Budzikiewicz H. A Fast Screening Method for the Identification of Siderophores from Fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. by Liquid Chromatography/Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 1999, 34, 281–290. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. J.; Kuo T. Y.; Hsieh F. C.; Chen P. Y.; Wang C. S.; Shih Y. L.; Lai Y. M.; Liu J. R.; Yang Y. L.; Shih M. C. Involvement of type VI secretion system in secretion of iron chelator pyoverdine in Pseudomonas taiwanensis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32950 10.1038/srep32950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density functional thermochemistry. III The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J. P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods V:Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. 10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehre W. J.; Radom L.; Schleye P. V. R.; Pople J. A.. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; John Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Burade S. S.; Saha T.; Bhuma N.; Kumbhar N.; Kotmale A.; Rajamohanan P. R.; Gonnade R. G.; Talukdar P.; Dhavale D. D. Self-Assembly of Fluorinated Sugar Amino Acid Derived α,γ-Cyclic Peptides into Transmembrane Anion Transport. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5948–5951. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burade S. S.; Shinde S. V.; Bhuma N.; Kumbhar N.; Kotmale A.; Rajamohanan P. R.; Gonnade R. G.; Talukdar P.; Dhavale D. D. Acyclic αγα-Tripeptides with Fluorinated- and Nonfluorinated-Furanoid Sugar Framework: Importance of Fluoro Substituent in Reverse-Turn Induced Self-Assembly and Transmembrane Ion-Transport Activity. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5826–5834. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuma N.; Burade S. S.; Bagade A. V.; Kumbhar N. M.; Kodam K. M.; Dhavale D. D. Synthesis and anti-proliferative activity of 3′-deoxy-3′-fluoro-3′-C-hydroxymethyl-pyrimidine and purine nucleosides. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 6157–6163. 10.1016/j.tet.2017.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.. et al. Gaussian 16, revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.