Abstract

Background:

Using the National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN) annual data report, U.S. national prevalence estimates for major birth defects are developed based on birth cohort 2010–2014.

Methods:

Data from 39 U.S. population-based birth defects surveillance programs (16 active case-finding, 10 passive case-finding with case confirmation, and 13 passive without case confirmation) were used to calculate pooled prevalence estimates for major defects by case-finding approach. Fourteen active case-finding programs including at least live birth and stillbirth pregnancy outcomes monitoring approximately one million births annually were used to develop national prevalence estimates, adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity (for all conditions examined) and maternal age (trisomies and gastroschisis). These calculations used a similar methodology to the previous estimates to examine changes over time.

Results:

The adjusted national birth prevalence estimates per 10,000 live births ranged from 0.62 for interrupted aortic arch to 16.87 for clubfoot, and 19.93 for the 12 critical congenital heart defects combined. While the birth prevalence of most birth defects studied remained relatively stable over 15 years, an increasing prevalence was observed for gastroschisis and Down syndrome. Additionally, the prevalence for atrioventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, omphalocele, and trisomy 18 increased in this period compared to the previous periods. Active case-finding programs generally had higher prevalence rates for most defects examined, most notably for anencephaly, anophthalmia/microphthalmia, trisomy 13, and trisomy 18.

Conclusion:

National estimates of birth defects prevalence provide data for monitoring trends and understanding the impact of these conditions. Increasing prevalence rates observed for selected conditions warrant further examination.

Keywords: population-based surveillance, birth defects, congenital anomalies, national estimates, United States

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Birth defects are congenital structural or genetic conditions that cause significant health and developmental complications. They remain a major contributor of infant mortality and lifelong disabilities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Vital Statistics Report, 2015; Decoufle, Boyle, Paulozzi, & Lary, 2001). Compared to children without birth defects, children with birth defects are more likely to experience hospitalizations as well as neurologic and cognitive impairments (Arth et al., 2017; Decoufle et al., 2001; Eide, Skjaerven, Irgens, Bjerkedal, & Oyen, 2006; Petterson, Bourke, Leonard, Jacoby, & Bower, 2007).

Overall, approximately 3–5% of births are affected by a birth defect (Bower, Rudy, Callaghan, Quick, & Nassar, 2010; CDC, 2008; Texas Birth Defects Registry, 2016). The prevalence of major birth defects collectively appears to remain stable, but variations can be seen for selected conditions, for example, increasing prevalence of gastroschisis (Jones et al., 2016; Kirby et al., 2013) and trisomy 18 (Langlois, Marengo, & Canfield, 2011); and decreasing prevalence of neural tube defects (Williams et al., 2015).

The United States lacks a national population-based surveillance program to track major birth defects, but most states have established systems to provide ongoing monitoring. However, variability in how programs collect and verify birth defects cases using different data sources hampers efforts to continuously generate reliable national estimates (Mai et al., 2015). In 2006, Canfield et al. provided the first national estimates for 21 birth defects obtained from population-based birth defects surveillance systems with active case-finding ascertainment methodology. The national estimates were updated in 2010 (Parker et al., 2010) and included an examination of the impact of pregnancy outcomes on prevalence estimates for the most common neural tube defects and trisomies. In this analysis, we provide more recent national estimates for an expanded list of major birth defects (including 12 critical congenital heart defects [CCHDs]), re-examine the variability in estimates for each condition, refine previous prevalence estimates on racial/ethnic prevalence differences, and examine the birth defects prevalence among the different birth cohort periods.

2 |. METHODS

The National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN) 2017 Congenital Malformations Surveillance Report included population-based data for up to 47 major birth defects from 39 population-based birth defects surveillance programs for birth cohort 2010–2014 (Lupo et al., 2017). Since programs use International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or modified ICD codes to identify potential birth defects cases (case ascertainment), data from the 2017 report were used to minimize any potential effect of the ICD coding transition in the United States (effective October 1, 2015). A call for data from the NBDPN Data Committee was sent to all state birth defects contacts in April 2017 with a data dictionary containing the requested conditions (Table S1). Aggregate state data by selected variables were submitted to the CDC for central processing and analyses, and to generate national estimates for selected major birth defects.

For this study, clinical and programmatic expertise was used to narrow the NBDPN birth defects list to 29 birth defects for inclusion given their public health importance and relatively consistent diagnostic accuracy at birth or soon after birth. These conditions cover a range of organ systems: central nervous (anencephaly, encephalocele, spina bifida without anencephaly); eye (anophthalmia/microphthalmia); cardiovascular (atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), coarctation of the aorta, common truncus/truncus arteriosus, double outlet right ventricle (DORV), Ebstein anomaly, hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), interrupted aortic arch, pulmonary valve atresia—with and without stenosis, single ventricle, tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC), transposition of the great arteries (TGA)—any type and specifically dextro-TGA (d-TGA), and tricuspid valve atresia—with and without stenosis); orofacial (cleft lip with and without cleft palate, cleft palate alone); gastrointestinal (esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula, rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis, small intestinal atresia/stenosis); musculoskeletal (clubfoot, diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, all limb deficiencies, omphalocele); and chromosomal (trisomy 13, trisomy 18, Down syndrome). The NBDPN list of birth defects was updated in 2014 (Mai et al., 2014), thus allowing the current presentation of national estimates for each of the 12 CCHDs being monitored as part of CCHD screening by sites that were able to distinguish CCHD (e.g., pulmonary valve atresia) from codes that broadly encompassed critical and noncritical CHD (e.g., pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis). These CCHDs include: coarctation of the aorta, common truncus/truncus arteriosus, DORV, Ebstein anomaly, HLHS, interrupted aortic arch, pulmonary valve atresia, single ventricle, TOF, TAPVC, d-TGA, and tricuspid valve atresia. To develop a national birth prevalence estimate for the total CCHD category, eight programs (Arkansas, California, Iowa, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah) provided de-duplicated total CCHD case information using the same dataset submitted for the annual report to ensure that cases were only counted once for the total CCHD category. Finally, two conditions were regrouped; limb deficiencies were merged into one category and orofacial clefts were split into three categories (cleft lip only, cleft palate only, and cleft lip with cleft palate). Infants with birth defects from more than one defect category were included in each applicable major defect category.

Programs were stratified into three case-finding methodologies: active case-finding (n = 14), passive case-finding with case verification (n = 13), and passive case-finding without case verification (n = 10). Programs using active case-finding review discharge diagnostic indices and hospital specific lists found in units providing obstetrical, neonatal, surgical, and pathology services to ensure accuracy and completeness of ascertainment of infants with major birth defects. Following initial identification of cases, medical records are abstracted from birth hospitals, pediatric referral hospitals, and other sources such as genetics laboratories. Programs with passive case-finding rely on mandated reporting by physicians or hospitals, or on linkage of existing administrative health data sources, such as hospital discharge and claims data, to identify cases. Some of these programs then conduct follow-up medical record review for selected or all reported cases to collect additional medical information to eliminate false positives or to further refine the case diagnosis, for example, distinguishing between gastroschisis and omphalocele.

Programs were included in the current national estimates if they use an active case-finding methodology that ascertains at least live birth and stillbirth cases. Program-specific pregnancy outcome inclusion criteria are available in the 2017 NBDPN Congenital Malformations Surveillance Report (Lupo et al., 2017). Data for this report covered deliveries occurring during 2010–2014. Programs meeting these case inclusion criteria (n = 14) include: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Georgia (Metropolitan Atlanta), Hawaii, Iowa, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah. The following states contributed to the national prevalence estimate table: Arkansas (2010–2013), California, Georgia (Metropolitan Atlanta), Iowa, Massachusetts (2011–2014), North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah. In a subanalysis to examine the impact of pregnancy outcome inclusion for selected central nervous system and chromosome conditions, 11 of these 14 programs provided case count by pregnancy outcomes (live birth, live birth and stillbirths, and all birth outcomes).

We used SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) for data cleaning and analysis. The findings were independently validated by a second data analyst. Crude prevalence estimates were calculated overall and stratified by five race/ethnicity categories: White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander non-Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic (other/unknown not displayed). For trisomy and gastroschisis cases, the data were also grouped into six maternal age categories: <20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40+ years (unknown not displayed). We applied a direct standardization method for observed prevalence to the annual U.S. live birth population (annual average for years 2010–2014) by maternal race/ethnicity for all defects and by maternal age for trisomies and gastroschisis (NBDPN, 2004). For this analysis, adjusted prevalence refers to the direct standardization method. The confidence intervals for prevalence estimates were computed using Poisson exact method. Confidence limits for estimated annual cases were based on the confidence limits for the national prevalence estimates using gamma intervals (Fay & Feuer, 1997).

The methodology used to calculate national prevalence estimates for this analysis was similar to two previous studies (Canfield et al., 2006; Parker et al., 2010) to allow for examination of change in the prevalence over the different birth cohort periods (non-overlapping confidence intervals). The category, “cleft lip with and without cleft palate,” was combined for this analysis to be consistent with previous presentations; however, the category, “limb deficiencies (reduction defects),” could not be collapsed across the time periods and was presented separately.

3 |. RESULTS

The population-based case counts and crude prevalence for major birth defects by state birth defects program primary case-finding methodology (active, passive, passive with case verification) are shown in Table S2. All other tables presented in this analysis use data from the 14 population-based active case-finding programs that met inclusion criteria for the national estimates analyses.

The pooled counts and crude prevalence for 29 major birth defects by maternal race/ethnicity for the 14 active case-finding programs are presented in Table 1; these programs cover a live birth population of 5,186,504 or 26% of all births occurring in the United States during the birth years 2010–2014. The most prevalent conditions observed overall for this analysis are clubfoot, Down syndrome, cleft lip with or without cleft palate, and pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis. Prevalences of these defects remained high when stratified by racial/ethnic groups in Table 1, although variations in lowest and highest prevalence rates by race/ethnicity were observed. Generally, Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) births showed the lowest prevalence for a number of the conditions, including anencephaly, AVSD, clubfoot, coarctation of the aorta, Ebstein anomaly, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroschisis, limb deficiencies (reduction defects), omphalocele, pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis, spina bifida, and transposition of the great arteries. Conversely, Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native (non-Hispanic) births had some of the highest prevalence rates for the conditions studied. Some of the conditions where Hispanic births had the highest prevalence include anencephaly, anophthalmia/microphthalmia, common truncus, Ebstein anomaly, single ventricle, TAPVC, transposition of the great arteries, rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis, and trisomy 21; while selected conditions with highest prevalence for non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native births include tricuspid valve atresia, gastroschisis, cleft lip alone, DORV, cleft lip with cleft palate, pulmonary valve atresia, and encephalocele.

TABLE 1.

Birth defects counts and prevalence (prevalence per 10,000 live births) by race/ethnicity, 14 active case-finding population-based programs, 2010–2014

| NH White Count Prev (95%CI) |

NH Black Count Prev (95% CI) |

Hispanic Count Prev (95%CI) |

NH Asian/Pacific islander Count Prev (95%CI) |

NH American Indian/ Alaska native Count Prev (95%CI) |

Totala Count Prev (95%CI) |

Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | |||||||

| Anencephalus | 486 | 108 | 529 | 31 | 13 | 1,274 | |

| 2.07 (1.89, 2.26) | 1.58 (1.29, 1.90) | 2.97 (2.72, 3.24) | 1.28 (0.87, 1.82) | 1.82 (0.97,3.12) | 2.46 (2.32, 2.60) | ||

| Encephalocele | 182 | 92 | 192 | 25 | 10 | 532 | |

| 0.77 (0.67, 0.89) | 1.34 (1.08, 1.65) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.67, 1.53) | 1.40 (0.67, 2.58) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | ||

| Spina bifida without anencephalus | 879 | 188 | 793 | 38 | 32 | 2,002 | |

| 3.74 (3.50, 3.99) | 2.74 (2.36, 3.16) | 4.45 (4.15, 4.77) | 1.57 (1.11, 2.16) | 4.48 (3.07, 6.33) | 3.86 (3.69, 4.03) | ||

| Eye | |||||||

| Anophthalmia/microphthalmia | 423 | 108 | 430 | 41 | 10 | 1,035 | 1 |

| 1.80 (1.63, 1.98) | 1.58 (1.29, 1.90) | 2.42 (2.19, 2.65) | 1.80 (1.29, 2.44) | 1.41 (0.67, 2.59) | 2.00 (1.88, 2.13) | ||

| Cardiovascular | |||||||

| Atrioventricular septal defect (endocardial cushion defect) | 1,300 | 433 | 814 | 91 | 29 | 2,739 | 2 |

| 5.62 (5.32, 5.93) | 6.35 (5.77, 6.98) | 4.66 (4.35, 4.99) | 3.81 (3.07, 4.68) | 4.41 (2.95, 6.33) | 5.37 (5.17, 5.58) | ||

| Coarctation of the aorta | 1,439 | 304 | 927 | 91 | 41 | 2,845 | 3 |

| 6.21 (5.89, 6.54) | 4.56 (4.06, 5.10) | 5.22 (4.89, 5.57) | 3.78 (3.04, 4.64) | 5.76 (4.14, 7.82) | 5.55 (5.34, 5.75) | ||

| Common truncus (truncus arteriosus or TA) | 141 | 42 | 133 | 14 | 4 | 344 | 1 |

| 0.60 (0.51, 0.71) | 0.61 (0.44, 0.83) | 0.75 (0.63, 0.89) | 0.61 (0.34, 1.03) | 0.56 (0.15, 1.44) | 0.67 (0.60, 0.74) | ||

| Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) | 355 | 142 | 274 | 37 | 15 | 845 | 4 |

| 1.56 (1.41, 1.74) | 2.10 (1.77, 2.47) | 1.60 (1.42, 1.80) | 1.67 (1.17, 2.30) | 2.50 (1.40, 4.13) | 1.69 (1.58, 1.81) | ||

| Ebstein anomaly | 192 | 29 | 162 | 14 | 6 | 410 | 5 |

| 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) | 0.42 (0.28, 0.61) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.58 (0.32, 0.97) | 0.84 (0.31, 1.83) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.87) | ||

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | 641 | 193 | 419 | 49 | 16 | 1,353 | |

| 2.73 (2.52, 2.95) | 2.82 (2.43, 3.24) | 2.35 (2.13, 2.59) | 2.03 (1.50, 2.68) | 2.24 (1.28, 3.64) | 2.61 (2.47, 2.75) | ||

| Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) | 125 | 54 | 83 | 14 | 5 | 289 | 6 |

| 0.58 (0.48, 0.69) | 0.88 (0.66, 1.15) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.67) | 0.64 (0.35, 1.08) | 0.84 (0.27, 1.97) | 0.62 (0.55, 0.70) | ||

| Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis | 2,207 | 739 | 1,747 | 163 | 53 | 5,003 | |

| 9.39 (9.00, 9.79) | 10.78 (10.02, 11.59) | 9.81 (9.36, 10.28) | 6.74 (5.75, 7.86) | 7.43 (5.56, 9.71) | 9.65 (9.38, 9.92) | ||

| Pulmonary valve atresia | 294 | 126 | 245 | 43 | 14 | 742 | |

| 1.25 (1.11, 1.40) | 1.84 (1.53, 2.19) | 1.38 (1.21, 1.56) | 1.78 (1.29, 2.40) | 1.96 (1.07, 3.29) | 1.43 (1.33, 1.54) | ||

| Single ventricle | 136 | 52 | 163 | 17 | 2 | 379 | 7 |

| 0.61 (0.52, 0.73) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 0.76 (0.44, 1.22) | 0.28 (0.03, 1.03) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.88) | ||

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) | 1,083 | 348 | 763 | 112 | 35 | 2,387 | |

| 4.61 (4.34, 4.89) | 5.08 (4.56, 5.64) | 4.29 (3.99, 4.60) | 4.63 (3.82, 5.58) | 4.90 (3.42, 6.82) | 4.60 (4.42, 4.79) | ||

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) | 219 | 66 | 348 | 54 | 12 | 712 | 8 |

| 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.26) | 1.96 (1.76, 2.18) | 2.25 (1.69, 2.93) | 1.69 (0.87, 2.95) | 1.39 (1.29, 1.50) | ||

| Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) | 866 | 209 | 649 | 61 | 24 | 1,849 | 9 |

| 3.82 (3.57, 4.08) | 3.12 (2.71, 3.57) | 4.09 (3.78, 4.42) | 2.83 (2.16, 3.63) | 3.46 (2.22, 5.15) | 3.80 (3.63, 3.98) | ||

| Dextro-transposition of great arteries(d-TGA) | 697 | 161 | 537 | 54 | 17 | 1,505 | 10 |

| 2.97 (2.75, 3.20) | 2.35 (2.00, 2.74) | 3.38 (3.10, 3.68) | 2.37 (1.78, 3.09) | 2.39 (1.39, 3.83) | 3.03 (2.87, 3.18) | ||

| Tricuspid valve atresia and stenosis | 341 | 146 | 288 | 37 | 11 | 833 | 11 |

| 1.59 (1.42, 1.76) | 2.14 (1.81, 2.51) | 1.65 (1.47, 1.86) | 1.59 (1.12, 2.19) | 1.60 (0.80, 2.87) | 1.69 (1.58, 1.81) | ||

| Tricuspid valve atresia | 198 | 79 | 144 | 24 | 8 | 458 | 12 |

| 0.97 (0.84, 1.12) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.70) | 0.89 (0.75, 1.05) | 1.07 (0.69, 1.60) | 1.65 (0.71, 3.25) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | ||

| Orofacial | |||||||

| Cleft lip with and without cleft palate | 2,334 | 389 | 1,861 | 221 | 107 | 5,021 | 13 |

| 10.68 (10.25, 11.12) | 6.55 (5.91, 7.23) | 10.59 (10.12, 11.08) | 9.35 (8.15, 10.66) | 15.21 (12.46, 18.38) | 10.25 (9.97, 10.54) | ||

| Cleft lip with cleft palate | 1,531 | 275 | 1,367 | 140 | 70 | 3,457 | |

| 6.51 (6.19, 6.85) | 4.01 (3.55, 4.51) | 7.68 (7.28, 8.10) | 5.79 (4.87, 6.84) | 9.81 (7.65, 12.39) | 6.67 (6.45, 6.89) | ||

| Cleft lip alone | 945 | 167 | 519 | 90 | 37 | 1,802 | 3 |

| 4.08 (3.82, 4.34) | 2.50 (2.14, 2.91) | 2.92 (2.68, 3.19) | 3.74 (3.01, 4.60) | 5.20 (3.66, 7.17) | 3.51 (3.35, 3.68) | ||

| Cleft palate alone | 1,545 | 278 | 982 | 149 | 48 | 3,067 | |

| 6.57 (6.25, 6.91) | 4.06 (3.59, 4.56) | 5.52 (5.18, 5.87) | 6.17 (5.22, 7.24) | 6.73 (4.96, 8.92) | 5.91 (5.71, 6.13) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||

| Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula | 652 | 148 | 314 | 39 | 13 | 1,183 | 14 |

| 2.77 (2.56, 2.99) | 2.16 (1.83, 2.54) | 1.98 (1.77, 2.21) | 1.61 (1.15, 2.21) | 1.82 (0.97, 3.12) | 2.37 (2.24, 2.51) | ||

| Rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis | 965 | 272 | 723 | 96 | 19 | 2,124 | 15 |

| 4.39 (4.12, 4.68) | 4.07 (3.60, 4.58) | 4.98 (4.62, 5.36) | 4.20 (3.40, 5.13) | 3.83 (2.31, 5.99) | 4.57 (4.38, 4.77) | ||

| Musculoskeletal | |||||||

| Clubfoot | 3,103 | 884 | 2,374 | 182 | 86 | 6,756 | 16 |

| 17.77 (17.15, 18.41) | 15.82 (14.80, 16.90) | 17.10 (16.42, 17.80) | 10.42 (8.96, 12.05) | 19.76 (15.80, 24.40) | 17.07 (16.67, 17.48) | ||

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 665 | 172 | 466 | 55 | 22 | 1,427 | 10 |

| 2.83 (2.62, 3.06) | 2.51 (2.15, 2.92) | 2.94 (2.68, 3.22) | 2.41 (1.82, 3.14) | 3.09 (1.94, 4.68) | 2.87 (2.72, 3.02) | ||

| Gastroschisis | 1,223 | 260 | 1,109 | 73 | 57 | 2,794 | |

| 5.20 (4.91, 5.50) | 3.79 (3.35, 4.28) | 6.23 (5.87, 6.61) | 3.02 (2.37, 3.80) | 7.99 (6.05, 10.35) | 5.39 (5.19, 5.59) | ||

| Limb deficiencies (reduction defects) | 1,221 | 400 | 934 | 64 | 32 | 2,722 | 1 |

| 5.20 (4.91, 5.50) | 5.84 (5.28, 6.44) | 5.25 (4.92, 5.59) | 2.81 (2.16, 3.58) | 4.50 (3.08, 6.35) | 5.27 (5.07, 5.47) | ||

| Omphalocele | 581 | 209 | 363 | 38 | 15 | 1,270 | |

| 2.47 (2.27, 2.68) | 3.05 (2.65, 3.49) | 2.04 (1.83, 2.26) | 1.57 (1.11, 2.16) | 2.10 (1.18, 3.47) | 2.45 (2.32, 2.59) | ||

| Chromosomal | |||||||

| Trisomy 13 | 296 | 121 | 231 | 35 | 5 | 743 | |

| 1.26 (1.12, 1.41) | 1.77 (1.46, 2.11) | 1.30 (1.14, 1.48) | 1.45 (1.01, 2.01) | 0.70 (0.23, 1.64) | 1.43 (1.33, 1.54) | ||

| Trisomy 18 | 703 | 203 | 529 | 90 | 13 | 1,683 | |

| 2.99 (2.77, 3.22) | 2.96 (2.57, 3.40) | 2.97 (2.72, 3.24) | 3.72 (2.99, 4.58) | 1.82 (0.97, 3.12) | 3.24 (3.09, 3.40) | ||

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 3,335 | 755 | 2,963 | 299 | 83 | 7,702 | |

| 14.18 (13.71, 14.67) | 11.01 (10.24, 11.83) | 16.64 (16.05, 17.25) | 12.37 (11.01, 13.86) | 11.63 (9.26, 14.42) | 14.85 (14.52, 15.19) | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; NH, non-Hispanic; Prev, prevalence.

Note: States contributing to the table’: Arizona (2010–2013), Arkansas (2010–2013), California, Delaware, Georgia (Metropolitan Atlanta), Hawaii (2012), Iowa, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, Utah. Total live births = 5,186,504. (1) Excludes Hawaii. (2) Arizona data excludes 2010, 2014. (3) South Carolina data excludes 2011. (4) Excludes Hawaii. Arizona data excludes 2010–2011, 2014. (5) Delaware data excludes 2011. (6) Excludes Hawaii. Arizona data excludes 2010–2011, 2014, Delaware data excludes 2010–2012, Puerto Rico data excludes 2010–2013, South Carolina data excludes 2010–2012. (7) Excludes Hawaii. Puerto Rico data excludes 2010–2013, South Carolina data excludes 2010–2013. (8) Delaware data excludes 2011, South Carolina data excludes 2010. (9) Excludes California. (10) Excludes Hawaii, Puerto Rico. (11) Excludes Utah. (12) Excludes Arizona, South Carolina. (13) Excludes South Carolina. (14) Excludes Puerto Rico. (15) Excludes Arizona, Puerto Rico. (16) Excludes Arizona, California, Hawaii, South Carolina, Utah.

Total includes other/unknown.

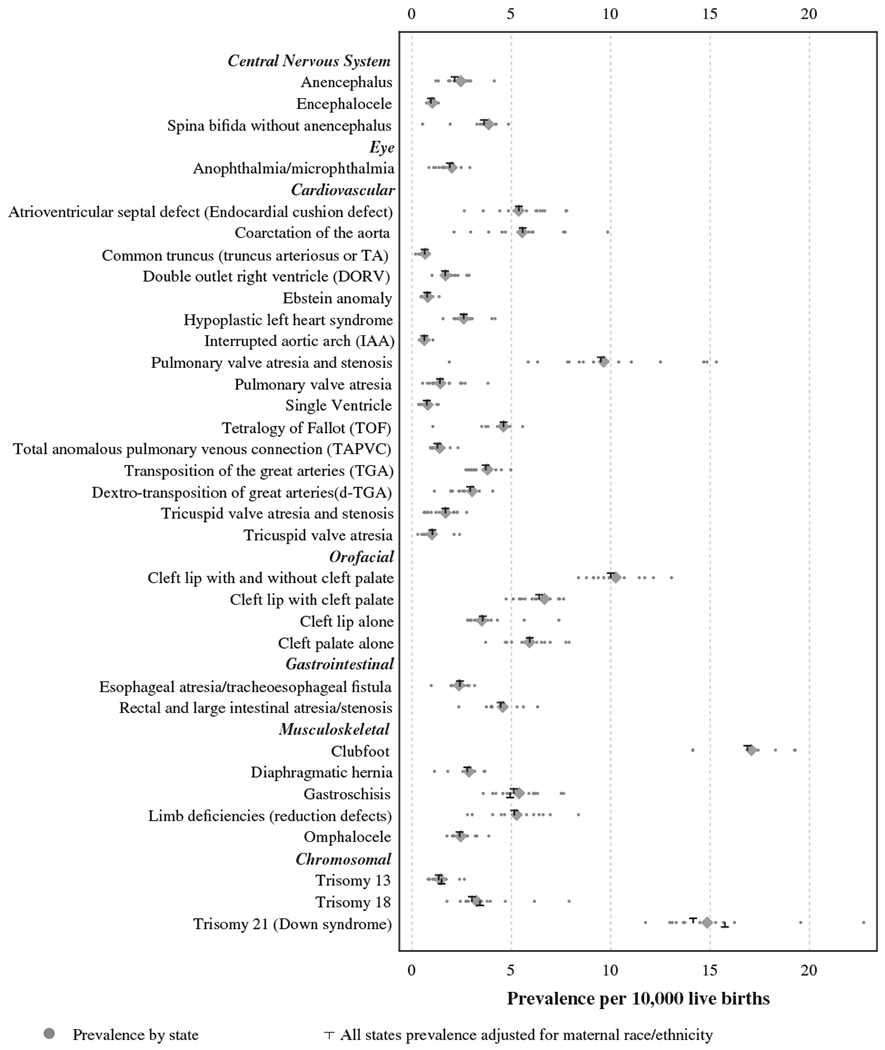

The prevalence distribution for 29 birth defects from active case-finding surveillance programs is shown in Figure 1. State-specific crude prevalence estimates are plotted together with the pooled crude and adjusted prevalence estimates for each defect. Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis and coarctation of the aorta show the greatest variability in prevalence across the 14 states, whereas the other heart defects in the analysis appear to have less variability. Other defects with degrees of variation include two trisomies (21 and 18), and to a lesser extent, limb reduction defects.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of prevalence of 29 selected defects from active population-based surveillance systems, 2010–2014 (n = 14)

Adjusted national estimates for 29 major birth defects are presented in Table 2. Of the conditions studied, the most prevalent overall, in descending order, were clubfoot (16.87/10,000 live births), Down syndrome (14.14/10,000 live births when adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, and 15.74/10,000 live births when adjusted for maternal age), cleft lip with or without cleft palate (10.00/10,000 live births), and pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis (9.51/10,000 live births, which was mostly driven by the prevalence of pulmonary valve stenosis). The national birth prevalence estimate for overall CCHDs that are targets for newborn screening is 19.93/10,000 live births (95% CI 19.74–20.13) (data not shown). The estimate takes into account potential over-counting of cases within the total CCHD category since cases with multiple CCHDs are only counted once (about 17% cases had more than one CCHD). This translates to about 1 case per 502 births or 7,847 infants with a CCHD each year in the United States (95% CI 7,770–7,925).

TABLE 2.

Adjusted national prevalence estimates (prevalence per 10,000 live births) and estimated number of births affected in the United States, 2010–2014

| Estimated national prevalence |

95% confidence interval |

Cases per births |

Estimated annual number of cases nationally |

95% confidence interval |

Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Central nervous system | ||||||

| Anencephalus | 2.15 | 2.03–2.28 | 1 in 4,647 | 847 | 798–899 | |

| Encephalocele | 0.95 | 0.87–1.04 | 1 in 10,502 | 375 | 342–411 | |

| Spina bifida without anencephalus | 3.63 | 3.46–3.80 | 1 in 2,758 | 1,427 | 1,362–1,495 | |

| Eye | ||||||

| Anophthalmia/microphthalmia | 1.91 | 1.79–2.03 | 1 in 5,243 | 751 | 704–801 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||||

| Atrioventricular septal defect (Endocardial cushion defect) | 5.38 | 5.17–5.59 | 1 in 1,859 | 2,118 | 2,036–2,202 | 2 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 5.57 | 5.36–5.79 | 1 in 1,795 | 2,194 | 2,111–2,279 | 3 |

| Common truncus (truncus arteriosus or TA) | 0.64 | 0.57–0.71 | 1 in 15,696 | 251 | 224–281 | 1 |

| Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) | 1.67 | 1.55–1.79 | 1 in 5,997 | 656 | 611–705 | 4 |

| Ebstein anomaly | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | 1 in 13,047 | 302 | 272–334 | 5 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | 2.60 | 2.46–2.75 | 1 in 3,841 | 1,025 | 969–1,083 | |

| Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) | 0.62 | 0.55–0.70 | 1 in 16,066 | 245 | 217–276 | 6 |

| Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis | 9.51 | 9.23–9.78 | 1 in 1,052 | 3,742 | 3,635–3,851 | |

| Pulmonary valve atresia | 1.41 | 1.30–1.52 | 1 in 7,104 | 554 | 513–598 | |

| Single ventricle | 0.75 | 0.67–0.83 | 1 in 13,351 | 295 | 265–328 | 7 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) | 4.61 | 4.42–4.80 | 1 in 2,171 | 1,813 | 1,738–1,891 | |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) | 1.28 | 1.18–1.38 | 1 in 7,809 | 504 | 466–545 | 8 |

| Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) | 3.71 | 3.54–3.89 | 1 in 2,695 | 1,461 | 1,392–1,532 | 9 |

| Dextro-transposition of great arteries(d-TGA) | 2.93 | 2.78–3.09 | 1 in 3,413 | 1,153 | 1,094–1,216 | 10 |

| Tricuspid valve atresia and stenosis | 1.68 | 1.57–1.81 | 1 in 5,938 | 663 | 617–712 | 11 |

| Tricuspid valve atresia | 1.03 | 0.93–1.13 | 1 in 9,751 | 404 | 366–444 | 12 |

| Orofacial | ||||||

| Cleft lip with and without cleft palate | 10.00 | 9.71–10.30 | 1 in 1,000 | 3,937 | 3,824–4,054 | 13 |

| Cleft lip with cleft palate | 6.40 | 6.18–6.63 | 1 in 1,563 | 2,518 | 2,431–2,608 | |

| Cleft lip alone | 3.56 | 3.39–3.74 | 1 in 2,807 | 1,402 | 1,336–1,472 | 3 |

| Cleft palate alone | 5.93 | 5.71–6.15 | 1 in 1,687 | 2,333 | 2,248–2,421 | |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula | 2.41 | 2.27–2.56 | 1 in 4,144 | 950 | 895–1,007 | 14 |

| Rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis | 4.46 | 4.27–4.66 | 1 in 2,242 | 1,756 | 1,680–1,835 | 15 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||

| Clubfoot | 16.87 | 16.46–17.30 | 1 in 593 | 6,643 | 6,478–6,811 | 16 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 2.79 | 2.64–2.94 | 1 in 3,591 | 1,096 | 1,038–1,157 | 10 |

| Gastroschisis | 5.12 | 4.92–5.32 | 1 in 1,953 | 2,015 | 1,938–2,095 | |

| Limb deficiencies (reduction defects) | 5.15 | 4.95–5.35 | 1 in 1,943 | 2,026 | 1,948–2,108 | 1 |

| Omphalocele | 2.40 | 2.26–2.54 | 1 in 4,175 | 943 | 889–999 | |

| Chromosomal | ||||||

| Trisomy 13 | 1.35 | 1.25–1.46 | 1 in 7,409 | 531 | 491–574 | |

| Trisomy 18 | 3.02 | 2.86–3.18 | 1 in 3,315 | 1,187 | 1,127–1,250 | |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 14.14 | 13.81–14.48 | 1 in 707 | 5,568 | 5,438–5,700 | |

| Adjusted for maternal age | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||

| Gastroschisis | 4.94 | 4.76–5.13 | 1 in 2,025 | 1,958 | 1,886–2,033 | |

| Chromosomal | ||||||

| Trisomy 13 | 1.49 | 1.38–1.60 | 1 in 6,717 | 590 | 548–635 | |

| Trisomy 18 | 3.43 | 3.26–3.60 | 1 in 2,918 | 1,359 | 1,294–1,426 | |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 15.74 | 15.39–16.10 | 1 in 635 | 6,242 | 6,103–6,384 | |

Note: Adjustment method is through direct standardization to the U.S. live birth population (average annual live births for years 2010–2014). States contributing to table: Arizona (2010–2013), Arkansas (2010–2013), California, Delaware, Georgia (Metropolitan Atlanta), Hawaii (2012), Iowa, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, Utah. Total live births = 5,186,504. (1) Excludes Hawaii. (2) Arizona data excludes 2010, 2014. (3) South Carolina data excludes 2011. (4) Excludes Hawaii. Arizona data excludes 2010–2011, 2014. (5) Delaware data excludes 2011. (6) Excludes Hawaii. Arizona data excludes 2010–2011, 2014, Delaware data excludes 2010–2012, Puerto Rico data excludes 2010–2013, South Carolina data excludes 2010–2012. (7) Excludes Hawaii. Puerto Rico data excludes 2010–2013, South Carolina data excludes 2010–2013. (8) Delaware data excludes 2011, South Carolina data excludes 2010. (9) Excludes California. (10) Excludes Hawaii, Puerto Rico. (11) Excludes Utah. (12) Excludes Arizona, South Carolina. (13) Excludes South Carolina. (14) Excludes Puerto Rico. (15) Excludes Arizona, Puerto Rico. (16) Excludes Arizona, California, Hawaii, South Carolina, Utah.

When examining the national prevalence estimates across three time periods (birth cohort 1999–2001 from Canfield et al. (2006); birth cohort 2004–2006 from Parker et al. (2010); and birth cohort 2010–2014 from this analysis), the estimated national prevalence remained relatively stable for most conditions (Table 3). However, an increasing prevalence for the second and third time periods were observed for gastroschisis and Down syndrome. For four conditions (AVSD, TOF, omphalocele, and trisomy 18) the birth prevalence from this time period appeared to be higher than the previous periods, while orofacial clefts showed a slight prevalence decrease.

TABLE 3.

National prevalence estimates (per 10,000 live births) across three time periods: 1999–2001, 2004–2006, and 2010–2014

| 1999–2001 (Canfield et al.a) |

2004–2006 (Parker et al.b) |

2010–2014 (current analysis) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated national prevalence |

95% CI | Estimated national prevalence |

95% CI | Estimated national prevalence |

95% CI | |

| Adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Central nervous system | ||||||

| Anencephalus | 2.51 | 2.31–2.70 | 2.06 | 1.92–2.20 | 2.15 | 2.03–2.28 |

| Encephalocele | 0.93 | 0.82–1.05 | 0.82 | 0.73–0.91 | 0.95 | 0.87–1.04 |

| Spina bifida without anencephalus | 3.68 | 3.45–3.92 | 3.50 | 3.31–3.68 | 3.63 | 3.46–3.80 |

| Eye | ||||||

| Anophthalmia/microphthalmia | 2.08 | 1.90–2.26 | 1.87 | 1.73–2.01 | 1.91 | 1.79–2.03 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||||

| Atrioventricular septal defect (Endocardial cushion defect) | 4.36 | 4.10–4.62 | 4.71 | 4.48–4.94 | 5.38 | 5.17–5.59 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | – | – | – | – | 5.57 | 5.36–5.79 |

| Common truncus (truncus arteriosus) | 0.82 | 0.71–0.93 | 0.72 | 0.63–0.81 | 0.64 | 0.57–0.71 |

| Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) | – | – | – | – | 1.67 | 1.55–1.79 |

| Ebstein anomaly | – | – | – | – | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | 2.43 | 2.24–2.63 | 2.30 | 2.15–2.45 | 2.60 | 2.46–2.75 |

| Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) | – | – | – | – | 0.62 | 0.55–0.70 |

| Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis | – | – | – | – | 9.51 | 9.23–9.78 |

| Single ventricle | – | – | – | – | 0.75 | 0.67–0.83 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) | 3.92 | 3.67–4.17 | 3.97 | 3.77–4.17 | 4.61 | 4.42–4.80 |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) | – | – | – | – | 1.28 | 1.18–1.38 |

| Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) | 4.73 | 4.46–5.00 | 3.00 | 2.83–3.17 | 3.71 | 3.54–3.89 |

| Tricuspid valve atresia and stenosis | – | – | – | – | 1.03 | 0.93–1.13 |

| Orofacial | ||||||

| Cleft lip with and without cleft palate | 10.47 | 10.08–10.87 | 10.63 | 10.32–10.95 | 10.00 | 9.71–10.30 |

| Cleft palate alone | 6.39 | 6.08–6.71 | 6.35 | 6.11–6.60 | 5.93 | 5.71–6.15 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula | 2.37 | 2.18–2.56 | 2.17 | 2.02–2.32 | 2.41 | 2.27–2.56 |

| Rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis | 4.81 | 4.54–5.08 | 4.68 | 4.54–4.91 | 4.46 | 4.27–4.66 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||

| Clubfoot | – | – | – | – | 16.87 | 16.46–17.30 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 2.94 | 2.73–3.15 | 2.61 | 2.45–2.77 | 2.79 | 2.64–2.94 |

| Gastroschisis | 3.73 | 3.49–3.97 | 4.49 | 4.28–4.69 | 5.12 | 4.92–5.32 |

| Reduction deformity, upper limbs | 3.79 | 3.55–4.03 | 3.49 | 3.30–3.67 | – | – |

| Reduction deformity, lower limbs | 1.90 | 1.73–2.07 | 1.68 | 1.56–1.81 | – | – |

| Limb deficiencies (reduction defects) | – | – | – | – | 5.15 | 4.95–5.35 |

| Omphalocele | 2.09 | 1.91–2.27 | 1.86 | 1.73–1.99 | 2.40 | 2.26–2.54 |

| Chromosomal | ||||||

| Trisomy 13 | 1.31 | 1.17–1.45 | 1.28 | 1.18–1.39 | 1.35 | 1.25–1.46 |

| Trisomy 18 | 2.31 | 2.12–2.50 | 2.64 | 2.48–2.80 | 3.02 | 2.86–3.18 |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 12.78 | 12.34–13.22 | 13.56 | 13.20–13.92 | 14.14 | 13.81–14.48 |

| Adjusted for maternal age | ||||||

| Chromosomal | ||||||

| Trisomy 13 | 1.33 | 1.19–1.47 | 1.26 | 1.16–1.37 | 1.49 | 1.38–1.60 |

| Trisomy 18 | 2.41 | 2.23–2.60 | 2.66 | 2.50–2.81 | 3.43 | 3.26–3.60 |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 13.65 | 13.22–14.09 | 14.47 | 14.11–14.83 | 15.74 | 15.39–16.10 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Note: For the current analysis, selected defects were added and categories for cleft lip and limb deficiencies were modified.

Canfield et al. (2006). National estimates and race/ethnic-specific variation of selected birth defects in the United States, 1999–2001. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 76:747–756.

Parker et al. (2010). Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 88:1008–1016.

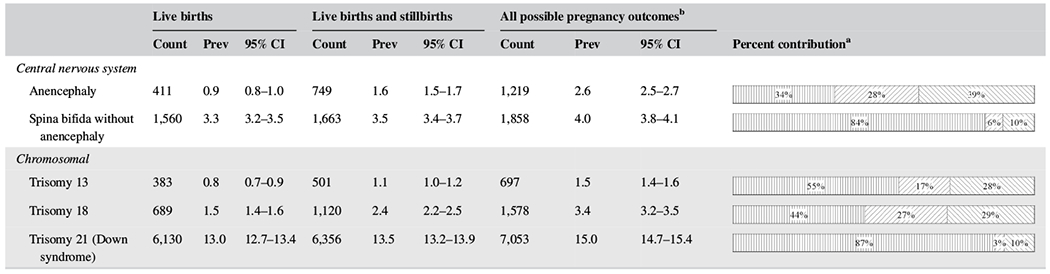

Table 4 presents the prevalence estimates for two central nervous system conditions and three chromosomal conditions by pregnancy outcomes (live birth, live birth and stillbirths, and all birth outcomes). Live birth cases contributed to only 34% of the anencephaly cases, 44% for trisomy 18 cases, and 55% for trisomy 13 cases, while they were much higher for Down syndrome (87%) and spina bifida (84%).

TABLE 4.

Birth defects counts and prevalence (per 10,000 live births), 2010–2014 by pregnancy outcome (n = 11 states)

|

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; Prev, prevalence.

Note: States contributing to the table: Arkansas (2010–2013), California, Georgia (Metropolitan Atlanta), Iowa, Massachusetts (2011–2014), North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, Utah. Total live births = 4,699,542.

Presented in the following order: Percent of live births, percent of live births and stillbirths, percent of all possible pregnancy outcomes.

All possible pregnancy outcomes includes non-live births and unknown.

4 |. DISCUSSION

National population-based estimates for 29 birth defects were calculated using confirmed diagnoses from medical records obtained from active case-finding birth defects surveillance programs. These programs examined approximately 5.2 million live births for the 2010–2014 birth cohorts, covering approximately 26% of the annual birth population of the United States. This analysis examined prevalence changes over three distinct birth cohort periods (Canfield et al., 2006; Parker et al., 2010) and found relative stability in the national prevalence estimates for most conditions examined with the exception of six conditions (gastroschisis, Down syndrome, trisomy 18, AVSD, TOF, and omphalocele), which showed an increase in the prevalence across one or more of the time periods included in the analysis.

The national prevalence estimates presented here are based on the best available evidence in the United States. These estimates utilize data on confirmed cases of birth defects from population-based surveillance programs broadly representative of the demographic and geographic distribution across the United States. We also provide data on prevalence by maternal race/ethnicity and maternal age, factors by which birth defects prevalence and outcomes have been shown to vary (Canfield et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). The prevalence for all presented defects was adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity. Additionally, for the three chromosomal anomalies included in this report, national estimates were also adjusted for maternal age. The estimated number of cases of trisomy 13, 18, and Down syndrome increased when maternal age was taken into account, due to higher prevalence among older mothers and perhaps also to the increasing proportion of all births over time occurring to older mothers (35+ years of age) (Hamilton, Martin, & Osterman, 2016).

Inclusion of cases with pregnancy outcomes other than live birth provides for more accurate estimates of prevalence of the selected defects. Data from the 11 birth defects surveillance programs with ascertainment of live births, stillbirths, and other pregnancy outcomes (Table 4) highlight the importance of conducting surveillance of neural tube defects, trisomies, and other conditions for all outcomes of pregnancy; in the case of anencephaly, trisomy 13, and trisomy 18, severe under-estimation of cases occurs when surveillance is conducted only among live births.

Evaluation of prevalence rates by maternal race/ethnicity may improve our understanding of risk factors for specific subpopulations and is useful when examining focused prevention efforts. Supplementation of folic acid has been shown to be important for the prevention of neural tube defects (Berry et al., 1999; Czeizel & Dudas, 1992; MRC Vitamin Study Research Group, 1991), and the lower blood folate levels found among Hispanic women of child-bearing age (Pfeiffer et al., 2012; Tinker, Hamner, Qi, & Crider, 2015) could help explain the higher prevalence rates of anencephaly and spina bifida among Hispanic women. Among non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders, rates of these conditions tend to be lower than among other racial ethnic groups. This is also true for cardiovascular and musculoskeletal birth defects, but there are no explanations for these lower rates. Orofacial defects are higher among non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders, which has been previously reported by Canfield and colleagues (Canfield et al., 2014). Rates of clubfoot, diaphragmatic hernia and gastroschisis tend to be higher among non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Natives. Variations in prevalence of maternal medical conditions and risk factors may contribute to the disparities in prevalence of these phenotypes. In a recent study of selected birth defects among American Indian/Alaskan Natives, Marengo et al. (2018) found a twofold increased prevalence of gastroschisis compared to non-Hispanic Whites; however, this association was no longer evident after adjustment for risk factors such as maternal age, education, diabetes, and smoking. This supports the hypothesis that such factors may play a role in the increased prevalence of these birth defects among the Native American/Alaskan Native population.

We also found a higher prevalence of limb deficiencies and omphalocele among non-Hispanic Blacks. Non-Hispanic Blacks also had a higher prevalence of trisomy 13 compared to other racial/ethnic populations, which may contribute to the higher prevalence of omphalocele, a frequently co-occurring birth defect with this condition.

Since the addition of newborn screening for CCHDs to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel in 2011, there has been a growing need for CCHD prevalence data to aid in monitoring and evaluation of screening. A previous NBDPN report noted state-specific individual CCHD defect prevalence (Mai et al., 2012), but this report provides the first national prevalence estimate of overall CCHDs that are targets for newborn screening using data from standard definitions among multiple active population-based surveillance programs in the United States. Mahle et al. (2009) provided an estimated prevalence of all congenital heart defects (CHDs) at 80–90/10,000, or 1 in 110 births (Mahle et al., 2009), with approximately 25% or 22.5/10,000 of those births having a CCHD. Two studies using data from the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (MACDP) estimated overall CCHD prevalence between 15.6–17.3/10,000 births (Oster et al., 2013; Reller, Strickland, Riehle-Colarusso, Mahle, & Correa, 2008). However, estimating the prevalence of CCHDs that are targets for newborn screening has been challenging given the variability in surveillance methodology, such as different case definitions, coding, and inclusion years. Furthermore, an infant can have more than one CCHD; thus, summation of individual defect subtype prevalence may result in over-estimation of overall CCHD prevalence. The de-duplicated pooled CCHD prevalence estimate of 19.93/10,000 births in this analysis is consistent with previous literature while providing a national estimate using a standard case definition for all CCHDs. These data provide baseline prevalence estimates for an important category of birth defects as newborn screening of babies born with these conditions continues.

4.1 |. Trends in birth defects

Clubfoot was observed to have the highest prevalence of the conditions examined in this paper. A previous NBDPN multistate collaborative project examining clubfoot (Parker et al., 2009) presented lower total prevalence than the prevalence reported in this analysis, but a similar pattern was observed across maternal race/ethnicity categories with Asian/Pacific Islander showing the lowest prevalence. However, clubfoot was only added to the NBDPN list of ascertained birth defects beginning with the 2014 annual report (starting with 2007 birth cohort year) so the prevalence could not be calculated for the other two papers presented in Table 3.

Most of the birth defects examined here exhibited relatively stable prevalence over time. Of interest, the current data show that neural tube defects are no longer declining, consistent with a recent report (Williams et al., 2015). Gastroschisis continues to increase in prevalence, although at a less rapid annual percent change (Jones et al., 2016; Kirby et al., 2013; Short et al., 2019). A slight increasing prevalence for Down syndrome when age-adjusted shows the impact of increasing maternal age on the overall prevalence compared to the nonadjusted age prevalence.

Our finding of an increase in trisomy 18 prevalence over time also has been reported in other studies (Langlois et al., 2011; Tonks, Gornall, Larkins, & Gardosi, 2013). Tonks et al. (2013) found a statistically significant increase for trisomy 18, but not for trisomy 13, in the United Kingdom between 1995–1999 and 2005–2009, which is generally consistent with our findings. Similarly, they also found a stronger association between advanced maternal age and trisomy 18 than for trisomy 13. The authors suggest that the increase in trisomy 18 in their study was likely due to a combination of a trend in earlier prenatal detection (especially among older women), and increasing maternal age during this time. A similar explanation is plausible in our finding, but needs further investigation.

Several other conditions showed increased prevalence rates at one or more time periods in this analysis, including AVSD, TOF, and omphalocele. The reasons for these findings are not clear. It is possible that the increase in omphalocele and AVSD are related to an increasing prevalence of trisomy 18 and Down syndrome, respectively. In MACDP, about 70% of the cases of AVSD were associated with Down syndrome (Miller et al., 2010). Additional research is needed to determine whether the trends in omphalocele and AVSD are also evident among infants with nonsyndromic (isolated) defects.

4.2 |. Variation in prevalence estimates between programs

Possible reasons for the observed variations in prevalence estimates of birth defects among surveillance programs include variations in clinical manifestations, reporting, case ascertainment (i.e., sensitivity), case classification and inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e., specificity, inclusion of possible/probable diagnoses), chance, and populations at risk (Mai et al., 2015). Birth defects with milder clinical manifestations are less likely to be recognized and reported consistently than more severe cases. Surveillance programs may differ in the extent to which severity of a clinical manifestation or objective assessment are used as criteria for inclusion in their database. Case ascertainment can encompass a spectrum of activities, such as (a) relying on vital records or passive reports from a limited number of data sources to seeking information actively from all possible data sources; (b) seeking information on live births only to seeking information on live births, still births, and pregnancy terminations; and (c) collecting data on birth defects only during the first year of life to collecting data on children with birth defects up to or beyond 2 years of age (Mai et al., 2016; Mai, Correa, et al., 2015). Approaches to case classification can vary from being based on information available from administrative datasets only to being based on diagnoses available from medical records with confirmatory objective tests or evaluations by clinical geneticists or dysmorphologists. Because of their underlying relatively low prevalence (i.e., <1 per 1,000 births), specific types of birth defects are expected to exhibit natural variations across regions, particularly when the numbers of births under observation per region tends to be relatively small (i.e., <100,000). Populations that differ in age, race/ethnicity, and other regional characteristics are likely to have different underlying susceptibilities and/or risk factors and this could manifest itself in differences in prevalence. The wider variation in prevalence observed for pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis was probably due to differences in severity criteria and coding utilization for inclusion; for clubfoot, variation could be due to differences in case classification and extent of exclusion of cases secondary to neural tube defects; and for Down syndrome, variation could be due to differences in the proportion of pregnancies to older age women and to ascertainment of cases among prenatally diagnosed cases and pregnancy terminations.

The NBDPN continually works to improve the quality of registry data from U.S. birth defects surveillance programs and has recently implemented quality standards for these programs to self-evaluate their activities in relation to national standards (Anderka et al., 2015). As more surveillance programs achieve higher levels of quality, future reports will be based on larger proportions of all births occurring nationwide and will become available in a more timely manner.

4.3 |. Strengths

The national estimates are calculated using only confirmed diagnoses obtained from medical records from active population-based birth defects surveillance programs that ascertain at least live birth and stillbirth cases. Adjusting the estimates to national live birth populations by race/ethnicity for all conditions allows the birth prevalence estimates to be generalized to the U.S. population, and the additional adjustment for age accounts for the age influence on the prevalence for trisomies.

The selected programs for inclusion in the analysis represented similar methodology to allow for comparisons across the three studies to examine trends over a 15-year period for major birth defects. Finally, this analysis presents for the first time the estimated prevalence for CCHDs using a standard definition across programs.

4.4 |. Limitations

Although the case information is obtained from medical records, the level of clinical detail obtained for this analysis is limited. The categories sometimes do not represent homogenous groups of cases; cases are included whether they were isolated, multiple, or syndromic cases. Cases with multiple birth defects could contribute to overestimation of the total number of affected births, but it is important to keep in mind that the proportion of cases that are isolated varies by defect. The only covariates available for this analysis were maternal race/ethnicity and age. As described above, other risk factors, such as maternal diabetes and smoking may contribute to differences in prevalence across different racial/ethnic groups or time periods. Finally, no formal trend test was performed to examine differences across the three time periods and changes in the ascertainment of these conditions within individual population-based surveillance programs could have occurred that potentially could affect the prevalence estimates; however, the pooled approach used should have attenuated individual program variations.

5 |. CONCLUSION

These national estimates provide valuable information to monitor the impact of major birth defects in the United States and to provide a benchmark for expected prevalence for 29 specific birth defects. Increasing prevalence rates observed for selected conditions warrant further examination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the NBDPN Data Committee for overseeing the state data collection and specifically to the following individuals for their assistance with regrouping their program CCHD data: Wendy Nembhard, Xiaoyi Shan, Cathleen Higgins, Nina Forestieri, Lindsay Denson, Adrienne Hoyt, Charles Shumate, Mary Ethen, Amy Nance, and Maria Huynh. We acknowledge the following programs for contributing data the NBDPN Annual Report and to this analysis: Arizona Birth Defects Monitoring Program; Arkansas Reproductive Health Monitoring System; California Birth Defects Monitoring Program; Colorado Responds To Children With Special Needs; Delaware Birth Defects Surveillance Project; Florida Birth Defects Registry; Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (Georgia); Illinois Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Reporting System; Iowa Registry For Congenital and Inherited Disorders; Kansas Birth Defects Information System; Kentucky Birth Surveillance Registry; Louisiana Birth Defects Monitoring Network; Maine Birth Defects Program; Maryland Birth Defects Reporting and Information System; Massachusetts Center For Birth Defects Research And Prevention; Michigan Birth Defects Registry; Minnesota Birth Defects Information System; Mississippi Birth Defects Registry; Nebraska Birth Defects Registry; Nevada Birth Outcomes Monitoring System; New Hampshire Birth Conditions Program; New Jersey Special Child Health Services Registry; New Mexico Birth Defects Prevention and Surveillance System; New York State Congenital Malformations Registry; North Carolina Birth Defects Monitoring Program; Ohio Connections For Children With Special Needs; Oklahoma Birth Defects Registry; Puerto Rico Birth Defects Surveillance and Prevention System; Rhode Island Birth Defects Program; South Carolina Birth Defects Program; Tennessee Birth Defects Registry; Texas Birth Defects Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch; Utah Birth Defect Network; Vermont Birth Information Network; Virginia Congenital Anomalies Reporting And Education System; West Virginia Congenital Abnormalities Registry, Education and Surveillance System; and Wisconsin Birth Defects Registry.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Anderka M, Mai CT, Romitti PA, Copeland G, Isenburg J, Feldkamp ML, … Kirby RS (2015). Development and implementation of the first national data quality standards for population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States. BMC Public Health, 15, 925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arth AC, Tinker SC, Simeone RM, Ailes EC, Cragan JD, & Grosse SD (2017). Inpatient hospitalization costs associated with birth defects among persons of all ages—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(2), 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry RJ, Li Z, Erickson JD, Li S, Moore CA, Wang H, … Correa A. (1999). Prevention of neural-tube defects with folic acid in China. China-U.S. collaborative project for neural tube defect prevention. The New England Journal of Medicine, 341(20), 1485–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower C, Rudy E, Callaghan A, Quick J, & Nassar N (2010). Age at diagnosis of birth defects. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 88, 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield MA, Honein MA, Yuskiv N, Xing J, Mai CT, Collins JS, … Kirby RS (2006). National estimates and race/ethnic-specific variation of selected birth defects in the United States, 1999–2001. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 76(11), 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield MA, Mai CT, Wang Y, O’Halloran A, Marengo LK, Olney RS, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2014). The association between race/ethnicity and major birth defects in the United States, 1999–2007. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), e14–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Update on overall prevalence of major birth defects—Atlanta, Georgia, 1978–2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(1), 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Report. (2015). Deaths: Final data for 2013. NVSR Volume 64, Number 2 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_02.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, & Dudás I (1992). Prevention of the first occurrence of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. The New England Journal of Medicine, 327, 1832–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoufle P, Boyle CA, Paulozzi LJ, & Lary JM (2001). Increased risk for developmental disabilities in children who have major birth defects: A population-based study. Pediatrics, 108(3), 728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide MG, Skjaerven R, Irgens LM, Bjerkedal T, & Oyen N (2006). Associations of birth defects with adult intellectual performance, disability and mortality: Population-based cohort study. Pediatric Research, 59(6), 848–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay MP, & Feuer EJ (1997). Confidence intervals for directly adjusted rates: A method based on the gamma distribution. Statistics in Medicine, 16, 791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, & Osterman MJK (2016). Births: Preliminary data for 2015 In National vital statistics reports (Vol. 65(3)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM, Isenburg J, Salemi JL, Arnold KE, Mai CT, Aggarwal D, … Honein MA (2016). Increasing prevalence of Gastroschisis—14 states, 1995–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(2), 23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby RS, Marshall J, Tanner JP, Salemi JL, Feldkamp ML, Marengo L, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of Gastroschisis in 15 states, 1995–2005. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 122(2), 275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois PH, Marengo LK, & Canfield MA (2011). Time trends in the prevalence of birth defects in Texas 1999–2007: Real or artifactual? Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 91(10), 902–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo PJ, Isenburg JL, Salemi JL, Mai CT, Liberman RF, Canfield MA, … The National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2017). Population-based birth defects data in the United States, 2010–2014: A focus on gastrointestinal defects. Birth Defects Research, 109(18), 1504–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahle WT, Newburger JW, Matherne GP, Smith FC, Hoke TR, Koppel R, … American Heart Association Congenital Heart Defects Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, and Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (2009). Role of pulse oximetry in examining newborns for congenital heart disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation, 120(5), 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Cassell CH, Meyer RE, Isenburg J, Canfield MA, Rickard R, … Kirby RS (2014). Birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2007 to 2011: Highlighting orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 100(11), 895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Correa A, Kirby RS, Rosenberg D, Petros M, & Fagen MC (2015). Assessing the practices of population-based birth defects surveillance programs using the CDC strategic framework, 2012. Public Health Reports, 130(6), 722–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Isenburg J, Langlois PH, Alverson CJ, Gilboa SM, Rickard R, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2015). Population-based birth defects data in the United States, 2008 to 2012: Presentation of state-specific data and descriptive brief on variability of prevalence. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 103(11), 972–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Kirby RS, Correa A, Rosenberg D, Petros M, & Fagen MC (2016). Public health practice of population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 22(3), E1–E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Riehle-Colarusso T, O’Halloran A, Cragan JD, Olney RS, Lin A, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2012). Selected birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2005–2009: Featuring critical congenital heart defects targeted for pulse oximetry screening. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 94(12), 970–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo LK, Flood TJ, Ethen MK, Kirby RS, Fisher S, Copeland G, … Mai CT. (2018). Study of selected major birth defects among the American Indian/Alaska native population: A multistate population-based retrospective study, United States, 1999–2007. Birth Defects Research 110(19):1412–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; MRC vitamin study research group. (1991). Prevention of neural tube defects: Results of the medical research council vitamin study. Lancet, 338, 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Siffel C, Lu C, Riehle-Colarusso T, Frías JL, & Correa A (2010). Long-term survival of infants with atrioventricular septal defects. The Journal of Pediatrics, 156(6), 994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. (1991). Prevention of neural tube defects: Results of the medical research council vitamin study. Lancet, 338(8760), 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN) (2004). Guidelines for conducting birth defects surveillance. In Sever LE (Ed.). Atlanta, GA: National Birth Defects Prevention Network. [Google Scholar]

- Oster ME, Lee KA, Honein MA, Riehle-Colarusso T, Shin M, & Correa A (2013). Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics, 131(5), e1502–e1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2010). Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 88(12), 1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Strickland MJ, Olney RS, Rickard R, Marengo L, . Meyer RE for the National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2009). Multistate study of the epidemiology of clubfoot. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 85(11), 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson B, Bourke J, Leonard H, Jacoby P, & Bower C (2007). Co-occurrence of birth defects and intellectual disability. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 21(1), 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer CM, Hughes JP, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, Berry RJ, Zhang M, … Johnson CL. (2012). Estimation of trends in serum and RBC folate in the U.S. population from pre- to postfortification using assay-adjusted data from the NHANES 1988–2010. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(5), 886–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, & Correa A (2008). Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998–2005. The Journal of Pediatrics, 153(6), 807–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short TD, Stallings EB, Isenburg J, O’Leary LA, Yazdy MM, Bohm MK, … Reefhuis J. (2019). Gastroschisis trends and ecologic link to opioid prescription rates—United States, 2006–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(2), 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Texas Birth Defects Registry. (2016). Report of defects among 1999–2011 deliveries. Retrieved from http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/birthdefects/data/BD_Data_99-11/Report-of-Birth-Defects-Among-1999-2011-Deliveries.aspx

- Tinker SC, Hamner HC, Qi YP, & Crider KS (2015). U.S. women of childbearing age who are at possible increased risk of a neural tube defect-affected pregnancy due to suboptimal red blood cell folate concentrations, National Health and nutrition examination survey 2007 to 2012. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 103(6), 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonks AM, Gornall AS, Larkins SA, & Gardosi JO (2013). Trisomies 18 and 13: Trends in prevalence and prenatal diagnosis—Population based study. Prenatal Diagnosis, 33, 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu G, Canfield MA, Mai CT, Gilboa SM, Meyer RE, … National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2015). Racial/ethnic differences in survival of United States children with birth defects: A population-based study. Journal of Pediatrics, 166(4), 819–26.e1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Mai CT, Mulinare J, Isenburg J, Flood TJ, Ethen M, … Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification—United States, 1995–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(1), 1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.