In early 2003, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (CoV) [1] spread around the world; ultimately, more than 8000 patients in 32 countries contracted SARS, many of whom died. Although gold standard methods, such as viral culture, can help diagnose SARS, these methods are by no means as efficient and rapid as PCR-based diagnostic tests. The speed and sensitivity of molecular diagnostic tests for SARS is often considerably greater than than that of serological and viral culture methods [2]. Our reported enhanced real-time PCR (ERT) method [3, 4] is ⩾100-fold more sensitive than conventional real-time PCR. The higher sensitivity of this method may reveal potential SARS CoV carriers who have SARS CoV levels that are undetectable by other methods, and the sensitivity of the ERT method may be particularly important for ensuring that patients who have had SARS are not infectious before discharge from the hospital [5].

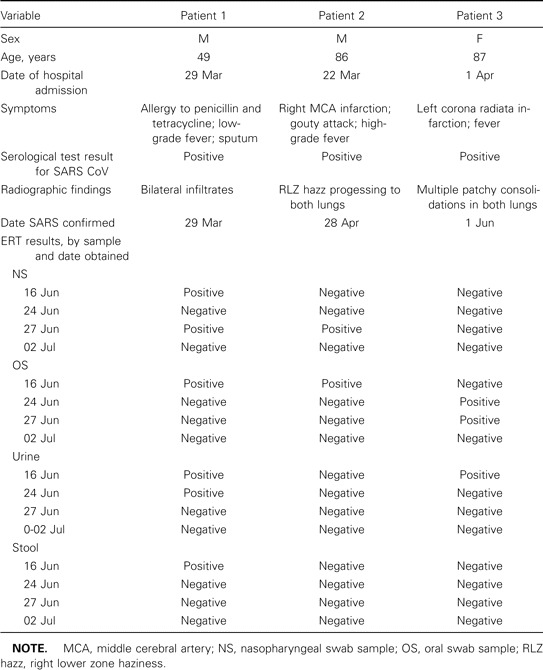

In collaboration with Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH; Hong Kong), samples obtained from 3 patients during recovery after SARS were analyzed (table 1). Six to nine weeks after the onset of infection, SARS CoV could still be detected by ERT in certain samples (table 1), indicating that, although clinical signs and symptoms had subsided and a host immune response had been mounted, viral clearance was not complete. Patient 1 was transferred on 17 June 2003 to the Wong Tai Sin Hospital (WTSH; Hong Kong), which was converted into a specialized center for convalescent care of patients with SARS during the epidemic, but he was returned to PMH because of recurrent pneumothorax, indicated by chest radiography on 18 June. The ERT method clearly demonstrated the presence of SARS CoV in all samples obtained from the patient on 16 June (table 1), which was 1 day before his transfer to WTSH. The possible relapse of infection in patient 1 after his transfer to another hospital indeed raises the question of how patients with SARS who have PCR results negative for SARS CoV should be handled [5]. Standardization of clinical criteria and PCR-based methods should be emphasized to ensure accurate diagnosis of SARS after hospital admission and prior to hospital discharge. More studies will be necessary to determine the infectivity status of patients who have ERT results positive for SARS CoV. The data suggest that medical professionals should verify whether residual viral particles present in recovering patients remain infectious and whether they may constitute the source of possible future outbreaks of infection.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics, clinical history, and laboratory results for patients recovering after severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (CoV) infection in Hong Kong, 2003.

Because SARS is a newly emerging disease that causes serious consequences, many countries have formulated contingency plans for possible future SARS outbreaks. One of the containment activities currently undertaken by the World Health Organization to prevent SARS from repeatedly becoming a widely established threat is to develop a robust and reliable diagnostic test [6], which will probably rely on PCR-based technology. Use of a highly sensitive method, such as the ERT method [3, 4] and a similar method that was reported recently [7], will be the first step toward more accurate screening of suspected SARS carriers and will minimize the occurrence of false-negative cases. Patients with false-positive cases can always be quarantined while awaiting further reconfirmation of infection. But patients with false-negative cases could be discharged into the community and pose a dangerous SARS threat to the public [8]. Therefore, stringent clinical criteria and use of the ERT method might effectively monitor patients recovering after SARS.

acknowledgments

We thank Sino-i.com, Dr. Cecilia W. B. Pang (Biotechnology Director, Information Technology and Broadcasting Branch, Commerce, Industry and Technology Bureau, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region), and Fung-Kwok Ma (New Century Forum), for facilitating this study.

Financial support. The Philip K. H. Wong Foundation, Kennedy Y. H. Wong, Pun-Hoi Yu, and the New Century Forum Foundation. C.G.W. is the principal investigator of the National Emergency Action on SARS Research (Beijing Group), supported by the Ministry of Public Health and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Conflict of interest. All authors: No conflict.

references

- 1.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): laboratory diagnostic tests. 29 April. 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/diagnostictests/en/print.html. Accessed 2 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau LT, Fung YW, Wong PF, et al. A real-time PCR for SARS-coronavirus incorporating target gene pre-amplification. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:1290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu ACH, Lau LT, Fung YW. Boosting the sensitivity of real-time PCR SARS detection by simultaneous reverse transcription and target gene pre-amplification. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1577–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200404083501523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsang OT-Y, Chau T-N, Choi K-W, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: relapse?. Hospital infection? Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1180–1. doi: 10.3201/eid0909.030395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): status of the outbreak and lessons for the immediate future. 20 May. 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/media/sars_wha.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang SS, Chen T-C, Yang J-Y, et al. Sensitive and quantitative detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection by real-time nested polymerase chain reaction. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:293–6. doi: 10.1086/380841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu AC. The difficulties of testing for SARS. Science. 2004;303:469–71. doi: 10.1126/science.303.5657.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]