Abstract

The risk of developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is about 9 times higher in women as compared to men. Our recent report, which used (SWRxNZB) F1 (SNF1) mouse model of spontaneous lupus, showed a potential link between immune response initiated in the gut mucosa at juvenile age (sex hormone independent) and SLE susceptibility. Here, using this mouse model, we show that gut microbiota contributes differently to pro-inflammatory immune response in the intestine and autoimmune progression in lupus-prone males and females. We found that gut microbiota composition in male and female littermates are significantly different only at adult ages. However, depletion of gut microbes causes suppression of autoimmune progression only in females. In agreement, microbiota depletion suppressed the pro-inflammatory cytokine response of gut mucosa in juvenile and adult females. Nevertheless, microbiota from females and males showed, upon cross-transfer, contrasting abilities to modulate disease progression. Furthermore, orchidectomy (castration) not only caused changes in the composition of gut microbiota, but also a modest acceleration of autoimmune progression. Overall, our work shows that microbiota-dependent pro-inflammatory immune response in the gut mucosa of females initiated at juvenile ages and androgen-dependent protection of males contributes to gender differences in the intestinal immune phenotype and systemic autoimmune progression.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, gut mucosa, gut microbiota, testosterone, autoimmunity, gender bias, inflammation

2. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an autoimmune disease, arises when abnormally functioning B lymphocytes produce autoantibodies to DNA and nuclear proteins, resulting in immune complexes that cause damage to the tissue [1]. While the triggers are not known, it is generally believed that SLE is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors [1–3]. Dietary factors can also have a profound impact on the gut and systemic immune responses [4–8]. Recent studies including ours that used human samples and rodent models have shown that gut microbiota composition influences the rate of disease progression and the overall disease outcome [9–13]. In addition to direct effects on the systemic and gut immune cell functions, dietary factors can change the composition of gut microbiota and affect autoimmune outcomes [10, 14, 15]. Recent reports from our laboratory demonstrated that minor dietary deviations such as changes in the pH of drinking water alter the composition of gut microbiota and incidence of autoimmune diseases [13, 16].

Importantly, there is a predisposition for SLE in women with a prevalence ratio of about 9:1 over men [17–19]. Numerous studies have suggested that sex hormones, estrogen in particular, can contribute to the onset and development of disease activities associated with SLE. Estrogen is reported to have inductive effects on autoimmune-related immune responses such as production of antibodies and pro-inflammatory cytokines [17, 19–21]. On the other hand, studies using mouse models have shown a role for testosterone as well as testosterone-influenced microbiota in determining the gender bias of autoimmune diseases [22–25].

Aforementioned reports suggest the involvement of gut microbial factors, in addition to sex hormones, in determining gender disparity in systemic autoimmunity. However, although it has been shown that lupus-susceptible germ-free (GF) mice develop disease [26, 27], whether microbiota affects the gut immune phenotype and modulates disease outcomes differently in males and females under lupus susceptibility are not known. Although lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice showed gender specific differences in gut microbiota close to disease onset [28], it is not known if these differences impact intestinal immune phenotype and autoimmune progression. In our recent study, for the first time, using lupus-prone (SWRxNZB)F1 (SNF1) micewe showed the potential contribution of immune response initiated in the gut mucosa in lupus associated gender bias [29]. We showed that pro-inflammatory immune response in the gut mucosa of lupus-prone females can be detected as early as at juvenile age, an age at which there are no sex hormones produced, much before the appearance of systemic autoimmunity in these mice. In another report, we showed that changes in the pH of drinking water provided to this mouse model has a profound effect not only on the composition of gut microbiota and disease progression, but also on the type of intestinal immune response [13].

Here we show that gut microbiota composition in lupus-prone SNF1 mouse male and female littermates, are different at adult ages, but not at juvenile age. Interestingly, depletion of gut microbiota starting at juvenile age suppressed the inflammatory phenotype, ameliorated systemic autoantibody production and disease incidence only in females. On the other hand, castration of male SNF1 mice resulted in altered gut microbiota and modest increase in autoantibody production and lupus incidence. Overall, these observations show that juvenile age onset and progressive increase in intestinal pro-inflammatory immune response, and adult age systemic autoantibody production in lupus-prone females are gut mucosa-microbiota interaction dependent. Further, androgen, microbiota dependently and/or independently, promotes protection of lupus-prone males from autoimmunity at adult ages and contributes to gender bias in lupus.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mice.

SWR, NZB and C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed, and breeding colonies were maintained, under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions at the animal facilities of Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). (SWRxNZB)F1 (SNF1) hybrids were generated by crossing SWR females with NZB males. In some experiments, male SNF1 mice were subjected to orchidectomy (castration) or mock surgery after anesthesia with ketamine and xylozine combination. In some experiments, mice were given a cocktail of broad spectrum antibiotics (Abx) as described in our recent report [30] to deplete the gut microbiota. Depletion of gut microbiota was confirmed by culture of fecal pellet suspension on brain heart infusion agar plates under aerobic and anaerobic conditions as described before [30]. Urine and tail vein blood samples were collected at different time-points to detect proteinuria and autoantibodies. All animal experiments were performed according to ethical principles and guidelines were approved by the institutional animal care committee of MUSC.

3.2. Proteinuria.

Urine samples collected weekly were tested for protein levels by Bradford assay (BioRad) against bovine serum albumin standards. Proteinuria was scored as follows; 0: 0-1mg/ml, 1: 1-2mg/ml, 2: 2-5 mg/ml, 3: 5-10mg/ml and 4: ≥ 10mg/ml. Mice that showed proteinuria >5 mg/ml were considered to have severe nephritis.

3.3. ELISA.

Levels of antibodies against nucleohistone and dsDNA in mouse sera were determined by ELISA as described in our recent reports [13, 29]. Briefly, 1.0μg/well of nucleohistone (Sigma-Aldrich) or dsDNA from calf thymus (Sigma-Aldrich) was coated as antigen, overnight, onto ELISA plate wells. Serial dilutions of the sera were made and total IgG and IgG isotypes against these antigens were detected using HRP-conjugated respective antimouse immunoglobulin isotype antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, eBioscience and Invitrogen). Serum testosterone and 17β-estradiol (estrogen) levels were determined using ELISA and EIA kits from ALPCO and Enzolifesciences respectively.

3.4. Quantitative PCR.

RNA was extracted from 2 cm pieces of the distal ileum or 1 cm pieces of distal colon using Isol-RNA Lysis Reagent (5prime) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared from RNA using first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and PCR was performed using SYBR-green master-mix (BioRad) and target-specific custom-made primer sets. A CFX96 Touch real time PCR machine (BioRad) was used and relative expression of each factor was calculated by the 2Δ-CT cycle threshold method against β-actin control.

3.5. 16S rRNA gene targeted sequencing and bacterial community profiling.

Total DNA was prepared from fresh fecal pellets of individual mice for bacterial community profiling as described in our recent reports [13, 16, 30]. Briefly, DNA in samples was amplified by PCR using 16S rRNA gene-targeted primer sets to assess the bacterial levels. V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed using Illumina MiSeq platform at MUSC genomic center. The sequencing reads were fed in to the Metagenomics application of BaseSpace (Illumina) for performing taxonomic classification using an Illumina-curated version of the GreenGenes taxonomic database which provided raw classification output at multiple taxonomic levels. The sequences were also fed into QIIME open reference operational taxonomic units (OTU) picking pipeline [31] using QIIME pre-processing application of BaseSpace. The OTUs were compiled to different taxonomical levels based upon the percentage identity to GreenGenes reference sequences (i.e. >97% identity) and the percentage values of sequences within each sample that map to respective taxonomical levels were calculated. The OTUs were also normalized and used for metagenomes prediction of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) orthologs employing PICRUSt as described before [28, 32–34]. The predictions were summarized to multiple levels and functional categories as well as microbial communities at different taxonomical levels were compared among different groups. Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profile Package (STAMP) [33] or web-based MicrobomeAnalyst application [35] were employed for analyzing OTU.Biom table and PICRUSt data for visualization and statistical analyses where appropriate.

3.6. Microbiota transfer.

Transfer of microbiota was performed as described in our recent reports [13, 16]. Briefly, homogenous suspension of cecum contents were made in chilled 0.1M bicarbonate buffer and administered to recipients by oral gavage. Suspension from one cecum was given to 5 mice. This process was repeated for three consecutive days using fresh preparations of microbes from additional donors. Fecal pellets collected from recipients 4-weeks post-transfer were subjected to 16S rRNA gene sequencing as described above. The recipients were tested for proteinuria and auto-antibody levels as described above.

3.8. Multiplex assay / suspension bead array.

Immune cells were enriched from collagenase digested intestinal tissues by Percoll gradient centrifugation and culture supernatants were tested for cytokine levels. Luminex multiplex assay based suspension bead array (SBA) was carried out using magnetic bead based cytokine/chemokine 26-plex or IFN-α and IFN-β 2-plex panels from eBiosciences and/or Invitrogen. Assay plates were read and concentrations were calculated using FlexMap3D instrument and xPONENT software (Luminex Corporation) at MUSC’s immune monitoring and discovery core.

3.7. Statistical analysis.

Proteinuria curves were analyzed using log-rank method (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/russell/logrank/) and the proteinuria scores were analyzed using Chi-square test. Two-tailed t-test or Mann Whitney test was also employed to calculate p-values where indicated. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism was used for calculating statistical significance. For some 16S rDNA data, Welch’s two-sided t-test was employed and the p-values were corrected from multiple tests using the Benjamini and Hochberg approach using STAMP or MicrobiomeAnalyst applications.

4. Results

4.1. Intestinal immune phenotype in SNF1 mice.

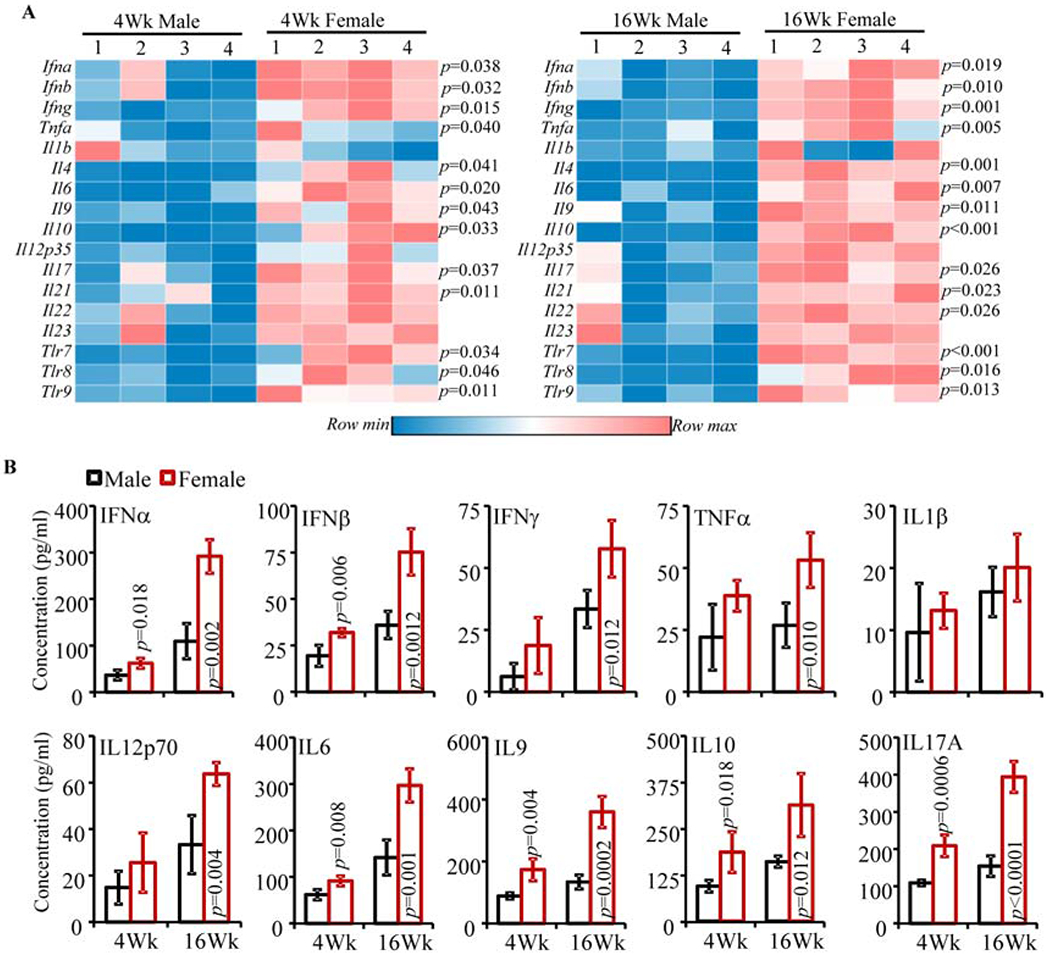

SNF1 mice develop lupus symptoms and proteinuria spontaneously and show gender bias in disease incidence similar to human SLE patients [36, 37]. Recently, we reported that significant amounts of circulating autoantibodies against nucleohistone and dsDNA are detectable in SNF1 mice at 16 weeks of age and severe nephritis indicated by high proteinuria is detected after 22 weeks of age [13, 29]. We also showed that about 80% of the female and 20% of the male SNF1 mice develop severe nephritis within 32 weeks. Here, to further characterize the gut immune phenotype in lupus-prone SNF1 mice, we determined mRNA and secreted protein levels of these key pro-inflammatory cytokines in both large and small intestines of 4- or 16- week old (pre-nephritic) male and female littermates. Quantitative PCR analysis shows that most pro-inflammatory factors including Il6, Il4, Il9, Il17, Il21, Ifna and Ifnb are expressed at higher levels in both colon (Fig. 1A) and ileum (Supplemental Fig. 1) of female SNF1 mice as compared to their age-matched male counterparts (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1), and lupus-resistant B6 mice (not shown). Significantly higher Ifng expression was detected primarily in the colon (large intestine) of SNF females. Further, the expression levels of endosomal TLRs, which are implicated in SLE (Tlr7, Tlr8 and Tlr9) [38–42], are also high in both large and small intestines of SNF females. Importantly, significant differences in the expression levels of most pro-inflammatory factors were detectable even in 4-week old (juvenile) mice and a robust increase in the expression levels of these factors in small and large intestines were detected at 16 weeks. To further validate the observations on inflammatory immune phenotype of lupus-prone female intestine, immune cells were enriched from the colon, cultured for 48 h in the absence of added stimuli, and supernatants were tested for the levels of spontaneously secreted cytokines. Figure 1B shows that the amounts of spontaneously released cytokines were significantly higher in females compared to males. Overall, in conjunction with our recent report showing activated T and B cells in the gut mucosa of lupus-prone female mice [29], these observations confirm that pro-inflammatory immune phenotype of gut mucosa in lupus-prone female mice is initiated independent of hormones and at juvenile age.

Fig. 1: Intestinal immune phenotype in SNF1 mice.

A) cDNA preparations from the distal colon of 4 and 16 week old lupus-prone male and female SNF1 mice were subjected to real-time quantitative PCR to assess the expression levels of key cytokines and endosomal TLRs. Expression levels of individual factors were calculated against the β-actin values and values from 4 male and 4 female SNF1 mouse littermates (tested individually) were used for generating the heat-map. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Distal ileum from male and female littermates were analyzed similarly and shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. B) Immune cells were enriched from collagenase digested single cell suspension of colon by Percoll gradient centrifugation, equal number of enriched cells (3x105/well in 150 μl medium) from each tissue were cultured for 48 h, and the spent media was subjected to SBA assay to detect the levels of spontaneously released cytokines. Mean±SD values (4 male and 4 female SNF1 mouse littermates; tested individually) are shown. Statistical analysis by two-sided Mann Whitney test. These experiments were repeated at least once using 4 mice/group and showed similar results.

4.2. Gut microbiota composition of lupus-prone SNF1 male and female mice is different at adult ages.

Differences in the intestinal immune phenotype in male and female SNF1 mice suggested a potential role for gut microbiota in this gender bias. Our initial studies used age-matched, but not littermate controlled, mice to determine the composition of fecal microbiota in younger (4 week old) and older (24-week old) SNF1 males and females. Principal component (PC) analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequence data of fecal samples from male and female mice showed profound gender specific clustering/separation only at adult age, but not the juvenile group (Supplemental Fig 2A). Accordingly, profound differences in the abundances of various microbial communities were observed only in 24-week old male and female mice (not shown). Further, SNF1 females at 24 weeks, the age at which severe nephritis begins to appear, but not 4 week old juvenile females, showed relatively lower gut microbial diversity compared to male counterparts (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

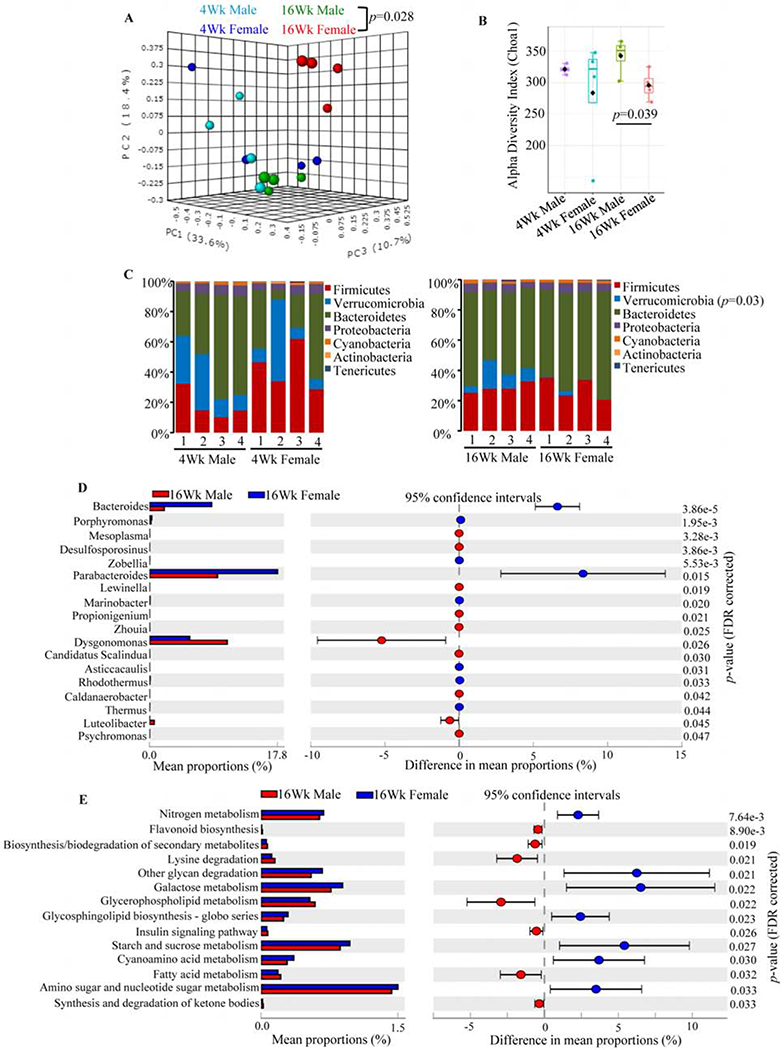

To unambiguously validate these observations, fecal pellets from 8 individually housed littermates (4 males and 4 females) of SNF1 mice were collected at 4 weeks and 16 weeks of age and subjected to microbial community profiling. As shown in Fig. 2A, PC analysis found gender specific β-diversity clustering of gut microbiota only with male and female mouse samples collected at 16 weeks of age. Further, as shown in Fig. 2B, α-diversity / species richness was significantly different only in 16 week fecal samples. Compilation of OTUs to different taxonomical levels showed that fecal microbiota in 16 week old females had significantly lower abundance of Verrucomicrobia phyla members and is relatively richer, albeit not significant statistically, in Bacteroidetes phyla members (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. 3). Interestingly, a significant increase in Bacteroidetes abundance was observed in females at 16 weeks of age compared to 4 weeks (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Since Fig. 2A showed gender dependent clustering only with samples from 16 week old mice, these samples were compared for abundances of microbial communities at the genus level. As observed in Fig. 2D, compared to male littermates, samples from females at 16 weeks of age had profoundly higher abundance of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides genus members, and lower Dysgonomonas genus members of Bacteroidetes phylum. Further, significant differences in large number of minor communities were observed between 16 week fecal samples of males and females. As observed in Supplemental Fig. 4B, significant age-dependent differences in the abundance of multiple microbial communities were observed in both males and females when samples collected at 4 weeks were compared to that of 16 weeks of age.

Fig. 2: Gut microbiota composition in lupus-prone SNF1 male and female mice.

Four male and 4 female SNF1 mouse littermates were individually housed upon weaning at 3 weeks of age, fresh fecal pellets were collected at 4 and 16 weeks of age, DNA preparations were subjected to 16S rRNA gene (V3/V4 region) -targeted sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq platform. The OTUs that were compiled to different taxonomical level based upon the percentage identity to reference sequences (i.e. >97% identity) and the percentage values of sequences within each sample that map to specific phylum and genus were calculated by employing 16S Metagenomics application of Illumina BaseSpace hub. OTU.Biom tables were also generated from the sequencing data employing QIIME preprocessing application of BaseSpace. A) OTU.Biom table data were used for generating principal component analysis (PCA) plots of samples representing β-diversity (Bray Curtis distance). B) α-diversity (Chao1)/species richness comparison of all 4 groups. C) Relative abundances of 16S rRNA gene sequences in fecal samples of individual mice at phyla level. D) Mean relative abundances of sequences representing major and minor microbial communities (>0.1 % of total sequences) at genus level. E) Normalized OTU.biom table was used for predicting gene functional categories using PICRUSt application and selected level 3 categories of KEGG pathway with statistically significant differences (between 16 week males and 16 week females) are shown. Statistical analyses were done employing two-sided Welch’s t-test and the p-values were FDR corrected using Benjamini and Hochberg approach. Additional analyses of this sequencing data are shown in Supplemental Figs. 3 & 4.

We then employed PICRUSt application for OTUs based in silico prediction of metabolic functions that may be associated with intestinal pro-inflammatory immune phenotype and the disease process in lupus-prone females. The PICRUSt analysis of data from 16-week old males and females showed that a variety of metabolic pathways such as glycan degradation and glycosphingolipid biosynthesis pathways, and nitrogen, amino sugar, nucleotide sugar, galactose, starch and sucrose metabolism pathways are overrepresented in females at 16 weeks of age (Fig. 2E). On the other hand, pathways involved in secondary metabolite synthesis and degradation, fatty acid, glycerophospholipid and lysine metabolism are underrepresented in 16 week old females compared to male counterparts. Although further analysis and additional studies are needed to understand if these metabolic pathways contribute to modulation of intestinal immune response and disease progression, these observations further support the notion that microbial communities are functionally different in lupus-prone adult males and females.

4.3. Gut microbiota depletion results in suppressed intestinal pro-inflammatory immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in female SNF1 mice.

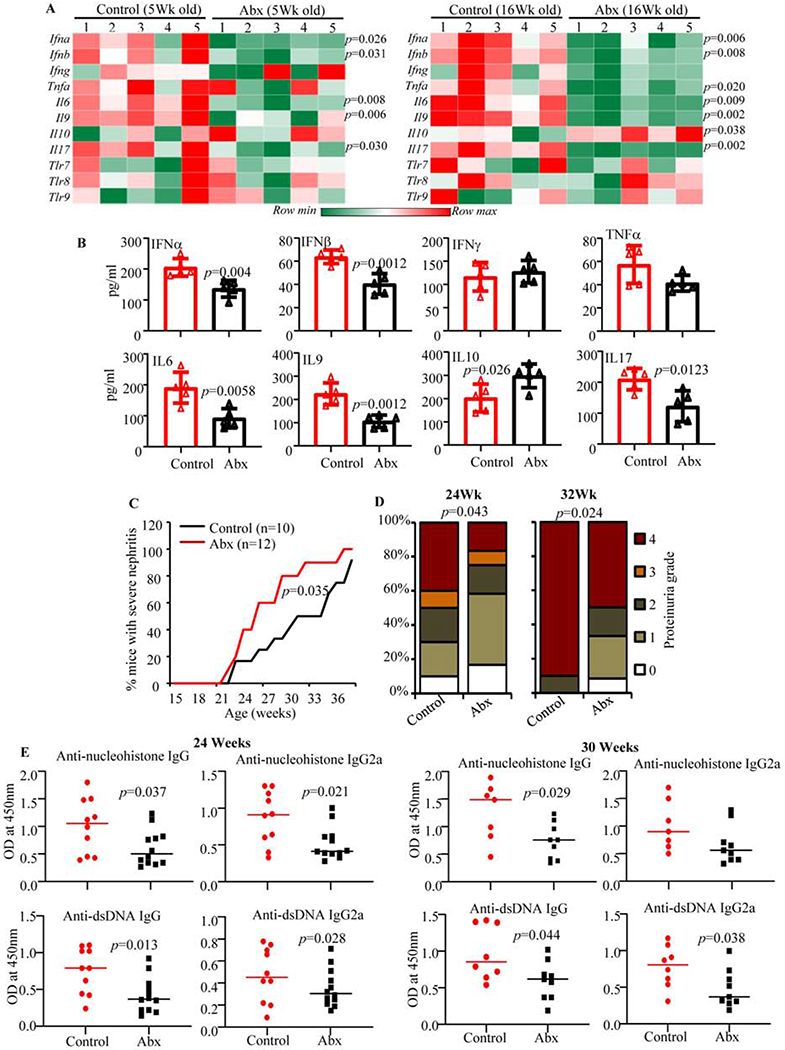

Although we observed a pro-inflammatory immune phenotype in female SNF1 mouse intestine as early as juvenile age, significant differences in the overall gut microbiota composition between males and females were detected only at adult ages. Nevertheless, we examined if microbiota depletion impacts the intestinal immune phenotype in these mice. Female SNF1 mice were given a broad-spectrum Abx in drinking water, starting immediately after weaning (3 weeks of age) to deplete the gut microbiota (Supplemental Fig. 5). First, intestinal immune phenotype of mice with intact and depleted gut microbiota was determined in cohorts of young (5-week old; pre-puberty) and adult (16-week old) females. As observed in Fig. 3A, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the colon of microbiota depleted females were significantly lower compared to control females, irrespective of the age. On the other hand, expression of Il10, an immune regulatory cytokine, was not diminished in microbiota depleted younger mice and significantly higher in microbiota depleted older mice compared to their counterparts with intact microbiota. Further, SBA analysis (Fig. 3B) revealed a similar trend, to that of mRNA levels, in the levels of cytokines secreted by intestinal immune cells. Interestingly, Tlr7, Tlr8, and Tlr9 expression levels in the colon of microbiota depleted females were not significantly different from that of control mice.

Fig. 3: Impact of gut microbiota depletion on intestinal immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in female SNF1 mice.

Female SNF1 mice were maintained on regular drinking water or drinking water containing broad-spectrum Abx starting at 3 weeks of age. A) cDNA preparations from the distal colon of 5 week and 16 week old control and Abx treated mice were subjected to real-time quantitative PCR to assess the expression levels of key cytokines and endosome TLRs. Relative expression levels of individual factors were calculated against the β-actin values and values from a total of 5 control and 5 Abx treated females (tested individually) were used for generating the heat-map. B) Immune cells were enriched from collagenase digested single cell suspension of whole colon of 16 week old mice (4 mice/group) by Percoll gradient centrifugation, equal number of cells (3x105/well in 150 μl medium) from each tissue were cultured for 48 h and the spent media was subjected to SBA assay to detect spontaneously released cytokines. Statistical analyses by two-sided Mann Whitney test. C) Urine samples collected from individual mice at different time-points were examined for proteinuria by Bradford assay. Percentage of mice with severe nephritis as indicated by high proteinuria (≥5mg/ml) is shown. p-values by log-rank test. D) Severity of proteinuria/nephritis in different groups of mice at different time points is shown. p-values by 2-sided Chi-Square test comparing number of mice with grade ≤2 and grade ≥3 proteinuria in different groups. E) Serum levels of total IgG and IgG2a antibodies specific to nucleohistone and dsDNA were assessed by ELISA for samples collected at 24 and 30 weeks of age. Mean ±SD of OD values of samples (1:1000 dilution) from 10 mice/group for controls and 12 mice/group for Abx treated mice are shown. p-values by two-sided Mann Whitney test. Experiments of panels A and B were repeated at least once using 3 mice/group and similar results were obtained.

Since depletion of gut microbiota resulted in suppression of pro-inflammatory gut immune phenotype, in female SNF1 mice, cohorts of mice were monitored for proteinuria and serum autoantibody levels. As shown in Fig. 3C, compared to mice with intact gut microbiota, severe proteinuria was significantly delayed in majority of the female SNF1 mice that were given Abx. While about 80% of control females developed severe nephritis by 31 weeks of age, only about 40% of the microbiota depleted mice showed similar degree of disease at this age. Fig. 3D which shows differences in the degree of proteinuria in Abx treated and control mice further supports the observation that overall disease progression was suppressed significantly in microbiota depleted females. In addition, determination of serum autoantibodies against dsDNA and nucleohistone revealed significantly lower autoantibody production in microbiota-depleted female SNF1 mice compared to control mice (Fig. 3E). These observations show significant contribution of gut microbiota to pro-inflammatory gut immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in female SNF1 mice.

4.4. Intestinal pro-inflammatory immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in male SNF1 mice are not profoundly impacted by gut microbiota depletion.

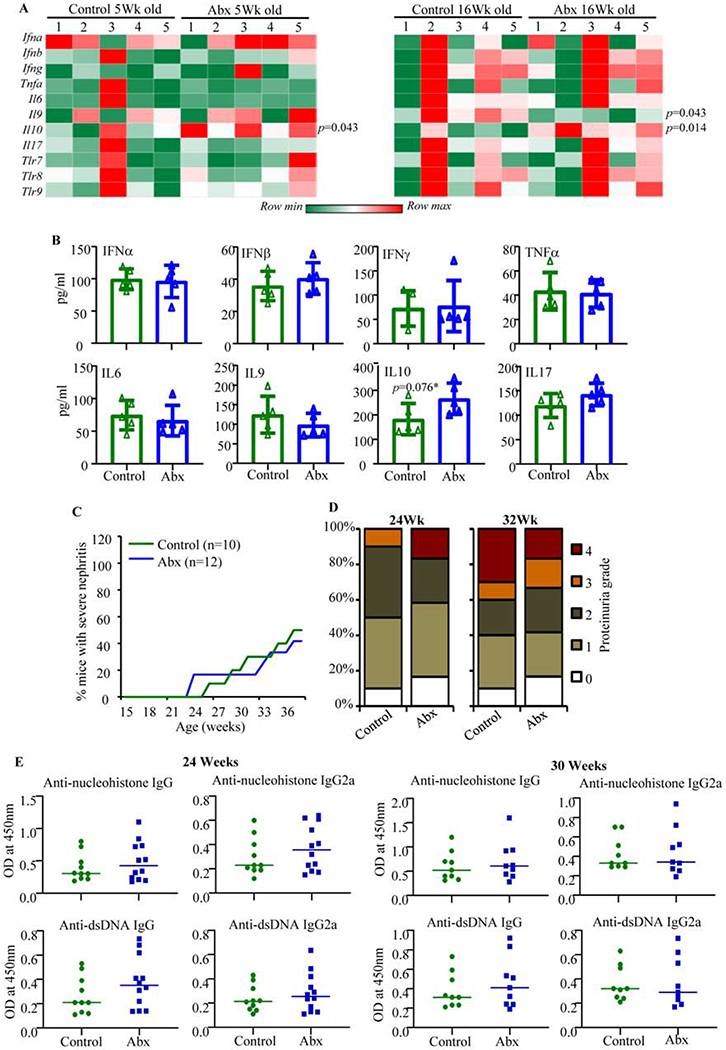

Aforementioned studies showed that depletion of gut microbiota suppresses pro-inflammatory gut immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in SNF1 females. In a parallel experiment, we determined the impact of microbiota depletion on gut immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in their male counterparts. Similar to the treatment of female mice, male SNF1 mice were given Abx starting at 3 weeks of age and the immune phenotypes of large intestine from cohorts of 5- and 16-week old mice were determined. Figs. 4A and 4B show that colon tissues of both control and Abx treated 5- and 16-week old male SNF1 mice expressed comparable levels of most pro-inflammatory cytokines, with the exception of IL9, and TLRs in the colon. Compared to control mice, Abx treated 16-week old male SNF1 mice showed lower Il9 mRNA expression in the colon (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, Il10 mRNA expression in the colon was higher in both 5- and 16-week old Abx treated males. However, the amounts of IL9 and IL10 secreted by immune cells enriched from the colon of Abx treated male SNF mice were not significantly different from that secreted by cells from control mice (Fig. 4B). To determine the impact of gut microbiota depletion on autoimmune progression in male SNF1 mice, cohorts of control and Abx treated mice were monitored for proteinuria and serum autoantibody levels. Unlike in females (Fig. 3), microbiota depletion had no significant impact on the appearance of clinical stage disease and the severity of proteinuria in male SNF1 mice (Figs. 4C and 4D). Correspondingly, systemic autoantibody levels were comparable in microbiota depleted and control male SNF1 mice (Fig. 4E). These observations, in association with the results of Fig. 3 suggest that the influence of microbiota on the gut immune phenotype and systemic autoimmune progression is more pronounced in female SNF1 mice than in their male counterparts.

Fig. 4: Impact of gut microbiota depletion on intestinal immune phenotype and autoimmune progression in male SNF1 mice.

Male SNF1 mice were maintained on regular drinking water or drinking water containing broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail starting at 3 weeks of age, and monitored as described for Fig. 3. A) Distal colon of 5-week and 16-week old control and Abx treated mice were subjected to real-time quantitative PCR as described for Fig. 3A. A total of 5 control and 5 Abx treated females (tested individually) were used for generating the heat-map. B) Supernatants from cultured immune cells, that were enriched from collagenase digested single cell suspension of whole colon of 16 week old mice (4 mice/group), were subjected to SBA assay as described for Fig. 3B. Statistical analyses by two-sided Mann Whitney test. C) Protein levels in urine samples. Percentage of mice with severe nephritis as indicated by high proteinuria (≥5mg/ml) is shown. p-values by log-rank test. D) Severity of proteinuria/nephritis in different groups of mice at different time points is shown. p-values by 2-sided Chi-Square test comparing number of mice with grade ≤2 and grade ≥3 proteinuria in different groups. E) Serum levels of total IgG and IgG2a antibodies specific to nucleohistone and dsDNA were assessed by ELISA for samples collected at 24 and 30 weeks of age. Mean ±SD of OD values of samples (1:1000 dilution) from 10 mice/group for controls and 12 mice/group for Abx treated mice are shown. p-values by two-sided Mann Whitney test. Experiments of panels A and B were repeated at least once using 3 mice/group. Note: experiments of Figs. 3 and 4 were conducted in parallel.

4.5. Microbiota transfer studies show different effects of male and female gut microbiota on autoimmunity in SNF1 mice.

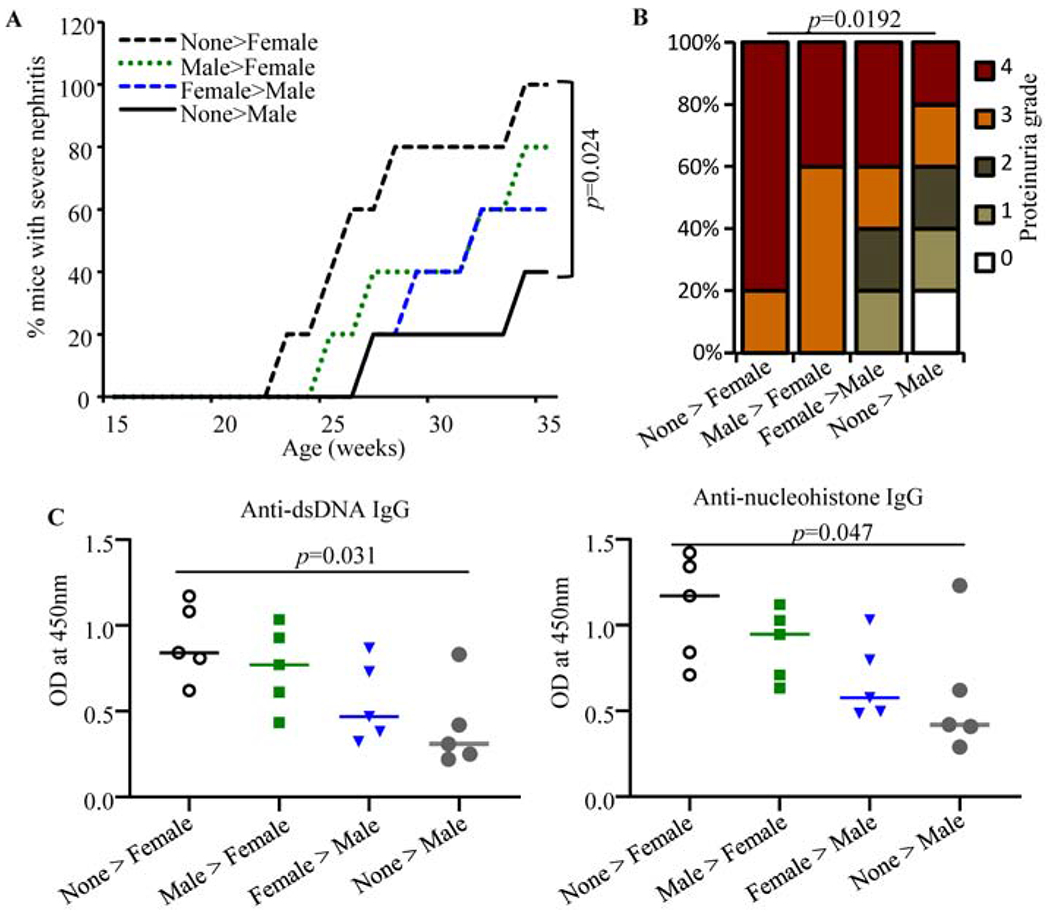

Since microbiota depletion impacted disease incidence primarily in female, but not male, SNF1 mice (Figs. 3 & 4), a microbiota transfer experiment was carried out to assess if microbes from only female, but not male, SNF1 mice modulate disease outcomes. Prepubescent SNF1 females and males received cecum content from 16-week-old males and females, respectively, by oral gavage and monitored, along with non-recipient controls of the same batch of mice, for proteinuria. Compared to that of non-recipients, the abundance of different phyla in fecal samples of recipient mice, 4 weeks post-transfer, were markedly different (Supplemental Fig. 6), suggesting that the transfer of cecum content caused changes in the overall composition of gut microbiota in them. Importantly, as expected, male and female SNF1 control mice that did not receive micobiota showed significant difference in the disease progression and incidence and proteinuria severity (Figs. 5A & 5B). Importantly, although not significant statistically, females that received male cecum microbes showed slower disease progression and proteinuria severity compared to non-recipient females. On the other hand, male SNF1 mice that received female cecum content showed modestly accelerated disease progression as well as relatively higher proteinuria severity compared to that of non-recipient males. In agreement with these observations, the serum levels of anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleohistone antibodies showed modest decrease in females that received male cecum content and modest increase in males that received female cecum microbes, compared to respective controls (Fig. 5C). Overall, albeit the observation that microbiota depletion did not affect disease outcome in males (Fig. 4), these observations indicate that gut microbiota in older male and female SNF1 mice are functionally different in terms of their ability to affect systemic autoimmunity.

Fig. 5: Effect of transfer of microbiota from adult male and female SNF1 mice in opposite gender.

Cecum microbial preparations from 16-week old male and female mice were given to juvenile female SNF1 mice. Five recipients or control mice/group were used. A) All 5 recipients in each group were monitored for disease progression, and percentage of mice with severe nephritis as indicated by high proteinuria is shown. p-values by log-rank test. B) Severity of nephritis in different groups of mice at 28 weeks of age is shown. p-values by 2-sided Chi-Square test comparing number of mice with grade ≤2 and grade ≥3 proteinuria in different groups. C) Serum levels of IgG antibodies against nucleohistone and dsDNA in samples collected at 28 weeks of age are shown. p-values by two-sided Mann Whitney test. Experiments of panels B-D were repeated with an additional 3 mice/group and obtained similar results.

4.6. Castration of male SNF1 mice causes changes in gut microbiota composition and accelerates autoimmune progression.

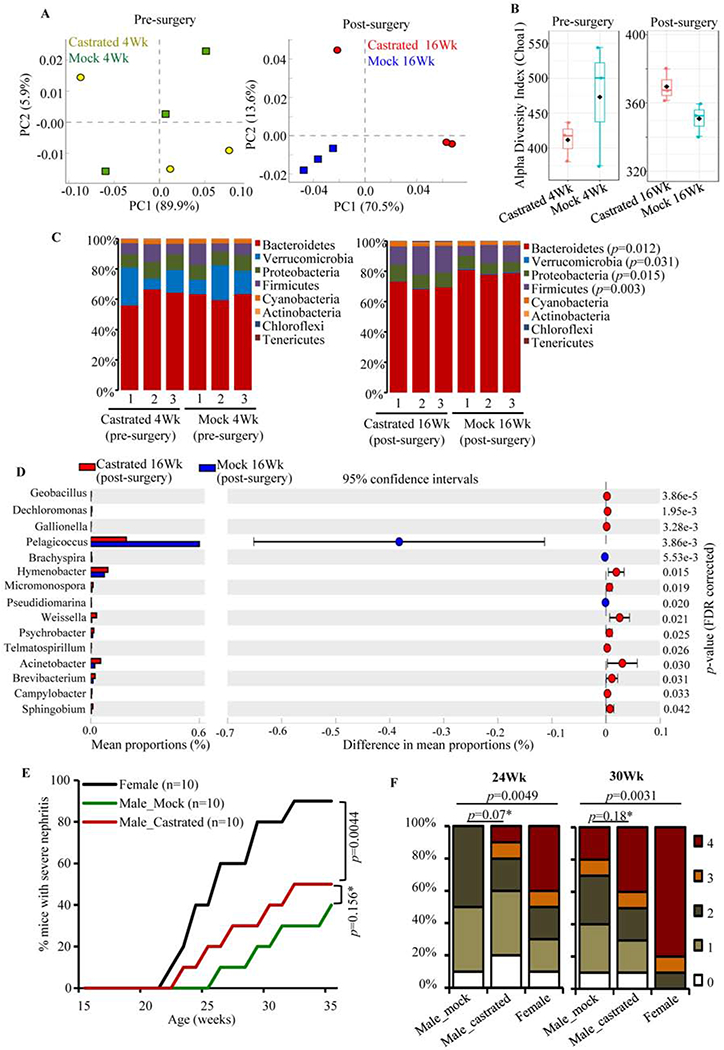

Our observations (Supplemental Fig. 4) show that both male and female SNF1 mice present age dependent changes in the gut microbiota composition. However, age-dependent β-diversity clustering (Fig. 2A) and impact of microbiota depletion (Figs. 3 & 4) were observed only with females, but not in males. This, along with the observation that gut microbiota from older females accelerates disease progression in males (Fig. 5), clearly shows that the gut microbes of female SNF1 mice contribute to higher disease incidence. However, although not evident upon microbiota depletion (Fig. 4), microbiota transfer experiments (Fig. 5) showed gut microbiota of adult males negatively impacts systemic autoimmunity to a certain extent. Previous studies have shown a protective role for the male sex hormone testosterone in lupus [24, 25]. It has also been shown that testosterone influences the gut microbiota composition [22, 23]. Therefore, to further understand the dynamics and delicate autoimmunity modulating function of microbiota of male SNF1 mice, we assessed the influence of androgen on gut microbiota. Juvenile mice were castrated to curtail testosterone production and sex hormone levels were determined (Supplemental Fig. 6). Cohorts of mice were examined for the changes in fecal microbiota composition. PC analysis graphs (Fig. 6A) show that samples from castrated and mock-surgery control mice segregated better at an adult age (post-castration) compared to juvenile age (pre-castration). Although the difference in microbial alpha diversity indices was not statistically significant in castrated and control mice (Fig. 6B), lower abundances of Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia and higher abundances of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla were observed in castrated males compared to controls (Fig. 6C). Fig. 6D shows that the abundance of multiple minor microbial communities (those with <1% of all identified sequences) at genus level were significantly different in castrated and non-castrated SNF1 males. Overall, these observations show that gut microbiota compositions are different in castrated and non-castrated male SNF1 mice and testosterone may be contributing to these differences.

Fig. 6: Impact of castration of SNF1 males on gut microbiota and autoimmune progression.

Four-week old SNF1 males were subjected to orchidectomy or mock-surgery (3 mice/group), fecal pellets were collected from individual mice before the surgery (pre-surgery) and at 20 weeks of age (post-surgery). DNA prepared from these fecal samples were subjected to 16S rRNA gene-targeted sequencing and analysis as described for Fig. 2. A) OTU.Biom table data were used for generating principal component analysis (PCA) plots. B) Alpha diversity graphs on species richness are shown. C) Relative abundances of 16S rRNA gene sequences in fecal samples of individual mice collected pre- and post- surgery at phyla level. D) Mean relative abundances of sequences compiled to genus level in post-surgery (20 week) samples are shown. Statistical analyses were done employing two-sided Welch’s t-test and FDR corrected using Benjamini and Hochberg approach. E) Cohorts of castrated or mock-surgery groups of male SNF1 mice, and age matched female SNF1 mice (10 mice/group) were monitored for disease progression as detailed for Fig. 3. Percentage of mice with severe nephritis as indicated by high proteinuria. p-values by log-rank test. F) Severity of nephritis in different groups of mice at 24- and 30-week time points are shown. Nephritis severity was scored based on urinary protein levels. p-values by 2-sided Chi-Square test comparing number of mice with grade ≤2 and grade ≥3 proteinuria in different groups.

We then we examined the impact of castration on autoimmune progression and disease incidence in SNF1 males. Castrated and mock-surgery control males, and age matched female SNF1 mice were monitored for proteinuria for up to 36 weeks of age. Although not significant statistically and not comparable with females, castrated males showed earlier onset and higher incidence of disease (Fig. 6E), subtly higher severity of nephritis (Fig. 7F), and higher anti-nucleohistone and anti-dsDNA antibody responses (Supplemental Fig. 8A). However, overall immune phenotype of large intestine was not significantly different in castrated and control mice (Supplemental Fig. 8B). These results along with the observation that castrated and non-castrated mice show differences in gut microbiota suggested that androgen, at least in part, directly and indirectly (through gut microbiota) contributes to the lower autoimmune susceptibility of male SNF1 mice.

Since castration caused changes in gut microbiota composition in SNF1 males (Fig. 5), we examined if microbiota from castrated and control male SNF1 mice impacts disease outcomes differently in female recipients. Cecum content from 20-week old castrated and mock-surgery control adult males were transferred to prepubescent female SNF1 mice. An additional control group received cecum content from age-matched female SNF1 mice. Differences in the overall gut microbiota composition in these recipients, as an indication of effective transfer of microbes, were assessed by 16s rDNA sequencing (Supplemental Fig. 9). As shown in Supplemental Fig. 10, female SNF1 mice that received microbes from castrated and mock-surgery control males showed comparable disease progression, proteinuria severity and, autoantibody levels, which were not significantly different from that of mice that received microbes from older females. Overall, these observations, in association with the impact of castration on gut microbiota composition and autoimmune progression (Fig. 6), suggest that the influence of testosterone-influenced gut microbiota on systemic autoimmunity in lupus-prone SNF1 mice may be subtle, and requires validation using gnotobiotic recipient lupus-prone mice.

5. Discussion

Gender bias is prevalent in many major autoimmune diseases, particularly in SLE [43–45]. The influence of sex hormones on lupus autoimmunity in general and gender bias in particular has been extensively studied. While estrogen has been linked to both cause and pathology of the disease [46–48], testosterone has generally been found to have a protective effect [25, 48]. Recent studies have linked testosterone-influenced gut microbes and their metabolites to gender bias in autoimmunity [22, 23]. It has been shown that SLE mouse models in GF background do develop disease, indicating that gut microbes are not required for systemic autoimmune response in them [26, 27]. However, the role of gut microbiota in gender bias associated with lupus has not yet been fully realized. In this regard, our recent report [29] showed, for the first time, that the immune phenotype of gut mucosa is significantly different in lupus-prone male and female SNF1 mice. Pro-inflammatory immune phenotype of gut mucosa appears in female mice at juvenile age, much before the production of sex hormones. Further, we found that gut mucosa of female SNF1 mice carry higher number of plasma cells compared to their male counterparts, even at juvenile age. These findings indicated that immune response initiated in the gut mucosa may be involved in the initiation and perpetuation of systemic autoimmunity and determining lupus associated gender bias. In the current study, we found significant influence of gut microbiota on intestinal pro-inflammatory immune phenotype and systemic autoimmune progression in females. Further, we show that androgen has an influence on gut microbiota composition in lupus model and it promotes modest protection from lupus autoimmunity.

Our observation that the gut microbiota composition of male and female lupus-prone mice differs significantly, only at adult ages, is in agreement with previous reports in other models [22, 23, 49, 50]. It has been suggested that the maternal microbiota acquired at young ages could be influenced by host factors such as hormones and environmental factors and eventually change/mature. In a disease-prone background, these changes could profoundly influence the disease outcome [10, 14, 15, 23, 51]. The disease susceptibility and changes/differences in the abundance of microbial communities, including increase in Bacteroidetes abundance and diminished diversity close to disease onset, in lupus-prone males and females are in agreement with previous reports [28, 34, 52]. Our observation that, compared to male littermates, lupus-prone SNF females had more pronounced changes in gut microbiota implies a role for gut microbes in promoting pro-inflammatory gut immune phenotype and rapid disease progression in females.

We found that both the colon and ileum of female SNF1 mice, compared to their male counterparts, express higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and endosomal TLRs at as early as juvenile age. Endosome TLRs such as TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are widely implicated in lupus [38–41]. Further, many of the therapeutic agents that are already being used in the clinic target the endosome pathway [53]. Pro-inflammatory cytokine factors such as IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-17 and IL-9 have also been linked to pathogenesis associated with SLE [38, 41, 54–57]. Importantly, signaling through endosomal TLRs triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as type 1 IFNs [41, 58, 59]. We found that, compared to those with intact gut microbiota, microbiota-depleted female SNF1 mice showed lower expression of only pro-inflammatory cytokines, but not the immune regulatory cytokine IL10 or endosomal TLRs. Interestingly, microbiota depletion associated suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the intestinal mucosa occurs predominantly in females, but not in males, at both pre-puberty and adult ages. This is intriguing because the composition of gut microbiota in male and female mice are comparable at younger ages. Nevertheless, these microbiota-dependent features in the gut mucosa of male and female SNF1 mice explain why suppression of systemic autoimmunity and the disease incidence is evident only in females, but not in males, upon microbiota depletion. Of note, previous studies using lupus-prone GF mice did not conclusively demonstrate a role for gut microbiota in autoantibody production and disease incidence [26, 27]. However, as observed upon selective depletion of gut microbiota in MRL/lpr mice [60], we found that treatment using broad-spectrum Abx suppresses autoimmunity in SNF1 females.

Importantly, our observations that gut microbiota compositions in SNF1 male and female littermates are significantly different only at adult ages suggest that differences observed in the intestinal immune phenotype of juvenile SNF1 males and females may not be due to difference in the composition of gut microbiota. Substantiating this notion, microbiota depletion resulted in diminished expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the intestine of not only adult, but also the juvenile, SNF1 females. This observation raises the possibility that differences in the magnitude/dosage of microbiota-gut mucosa interaction, rather than the microbiota composition, is responsible for differences in the gut immune phenotypes of male and female SNF1 mice at juvenile age. On the other hand, low dose gut mucosa-microbiota interaction produces a modest cytokine response in juvenile males. Importantly, at adult ages, differences in the composition of gut microbiota, in addition to differences in the magnitude of microbiota-gut mucosa interaction, could contribute to differences in the gut immune phenotypes of lupus-prone males and females. This is evident from the fact that the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are much higher in adult SNF females compared to prepubescent mice. The ability of cecum microbes from adult males and females, upon transfer to opposite genders, to modulate the disease progression further substantiates this notion.

Higher expression levels of microbiota interacting receptors such as TLRs in the gut mucosa could contribute to higher expression of pro-inflammatory factors in the female intestine and the disease associated gender bias. A likely scenario, based on our qPCR data, is that higher levels of TLRs, such as TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, in the gut mucosa of lupus-prone females even at juvenile age could facilitate higher dose interaction with gut microbiota, resulting in more pronounced inflammatory cytokine response in them. Previous studies have shown that TLR7 and TLR8 stimulation promotes significantly higher pro-inflammatory cytokine response in females than in males [38–41]. A recent study using mouse models has shown that dosage of X-linked TLR8 plays a major role in the higher incidence of SLE in females [41]. Another study using samples from lupus patients has demonstrated that TLR7 ligands induce higher IFN-α production in females [38].

While the role of gut microbiota on intestinal immune phenotype and disease progression in juvenile and adult female SNF1 mice was apparent, the influence of gut microbes in their male counterparts and its contribution to the disease associated gender bias was not so evident from our microbiota -depletion and -transfer studies. A potential contributor to this ambiguity could be the male sex hormone, testosterone. It has been reported by others [24, 25, 48, 61] that testosterone alone may have a disease protective effect in lupus. Previous reports have also shown that testosterone can also shape the gut microbiota [22, 23]. In agreement with these reports, we found that castration of male SNF1 mice to curtail testosterone levels not only changed the overall composition of gut microbiota, but also accelerated the disease progression. However, our microbiota transplant studies showing comparable effects in female mice by androgen-influenced and non-influenced gut microbiota from castrated males, suggest that the impact of testosterone shaped gut microbiota in SNF1 mice could be subtle. A note of caution on this interpretation is that microbiota transfer experiments in SPF mice are susceptible to a multitude of confounding variables including the effectiveness of transplant, source of donor microbiota, impact of a native recipient flora on donor microbe induced effects. Hence, reaching a clear conclusion without using gnotobiotic recipients is challenging. Nevertheless, our results support the notion that testosterone promotes, directly and/or microbiota dependently, protection from autoimmunity and contributes to lupus associated gender bias in SNF1 mice.

In conclusion, our study, for the first time, demonstrates distinct roles for gut microbiota in lupus-prone female and male mice contributing to gender bias in the intestinal immune phenotype and the disease outcomes. In females, gut microbiota appears to have composition-independent, gut mucosa interaction-dose dependent, role in promoting intestinal pro-inflammatory immune response as early as at juvenile age and eventual systemic autoimmunity. On the other hand, androgen appears to contribute to the protection of male SNF1 mice from the disease indirectly and/or microbiota dependently. Hence, comprehensive studies using lupus-prone GF mice are needed in the future to delineate the microbiota-dependent and -independent mechanisms of gender bias in lupus autoimmunity and to validate our observations in SPF mice.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Intestine of juvenile female lupus-prone SNF1 (SWRxNZB) F1 (SNF1) mice expresses higher pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Gender specific difference in gut microbiota appears only at adult age.

Depletion of gut microbiota modulates autoimmune progression in females, but not in males.

Microbiota transfer studies suggest gut microbes from older males and females are functionally different in terms of modulating systemic autoimmunity.

Orchidectomy alters gut microbiota composition and causes modest acceleration of autoimmune progression in males.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by internal funds from MUSC, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R21AI136339, R01AI138511 and R01AI073858, and Lupus research Institute (LRI) award to C.V. and P60AR062755 (NIH/NIAMS) to G.G. through a pilot grant to C.V. B.M.J. performed the experiments and reviewed the paper, M.C.G. performed the experiments and reviewed the paper, R.B. performed the experiments, R.G. performed experiments and reviewed the paper, G.G. reviewed the paper, and C.V. designed the study, performed the experiments, and wrote the paper. Dr. Vasu is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data and analysis. The authors are thankful to MUSC’s DLAR Veterinary staff for mouse castration service. The authors are also thankful to Cell and Molecular Imaging, Pathology, Proteomics, immune monitoring and discovery, and flow cytometry cores of MUSC for the histology service, microscopy, real-time PCR, FACS and multiplex assay instrumentation support. We also thank Drs. Raad Z Gharaibeh, Cory R. Brouwer, and Anthony A Fodor, Department of Bioinformatics and Genomics, UNC Charlotte for the initial guidance on analysis of MiSeq data and valuable comments and suggestions.

Abbreviations:

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SNF1 mice

(SWRxNZB)-F1 mice

- nAg

nuclear antigen

- PP

Peyers’ patch

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- LP

Lamina Propria

- SI

small intestine

- GF

germ-free

- SPF

specific pathogen free

- TLR

toll-like receptors

- Abx

antibiotic cocktail

- MUSC

Medical University of South Carolina

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- dsDNA

double stranded DNA

- OTU

operational taxonomic unit

- SBA

suspension bead array

- PC

Principal component

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement: Authors do not have any conflict(s) of interest to disclose.

References:

- [1].Li L, Mohan C. Genetic basis of murine lupus nephritis. Semin Nephrol, 2007;27:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gualtierotti R, Biggioggero M, Penatti AE, Meroni PL. Updating on the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev, 2010. 10:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Webber D, Cao J, Dominguez D, Gladman DD, Levy DM, Ng L et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) genetic susceptibility loci with lupus nephritis in childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE. Rheumatology, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hsieh CC, Lin BF. Dietary factors regulate cytokines in murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev, 2011;11:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Muthukumar AR, Jolly CA, Zaman K, Fernandes G. Calorie restriction decreases proinflammatory cytokines and polymeric Ig receptor expression in the submandibular glands of autoimmune prone (NZB x NZW)F1 mice. Journal of clinical immunology, 2000;20:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen S, Sims GP, Chen XX, Gu YY, Chen S, Lipsky PE. Modulatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human B cell differentiation. Journal of immunology, 2007;179:1634–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pelajo CF, Lopez-Benitez JM, Miller LC. Vitamin D and autoimmune rheumatologic disorders. Autoimmun Rev, 2010;9:507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Terrier B, Derian N, Schoindre Y, Chaara W, Geri G, Zahr N et al. Restoration of regulatory and effector T cell balance and B cell homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus patients through vitamin D supplementation. Arthritis research & therapy, 2012;14:R221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Azzouz D, Omarbekova A, Heguy A, Schwudke D, Gisch N, Rovin BH et al. Lupus nephritis is linked to disease-activity associated expansions and immunity to a gut commensal. Ann Rheum Dis, 2019;78:947–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zegarra-Ruiz DF, El Beidaq A, Iniguez AJ, Lubrano Di Ricco M, Manfredo Vieira S, Ruff WE et al. A Diet-Sensitive Commensal Lactobacillus Strain Mediates TLR7-Dependent Systemic Autoimmunity. Cell Host Microbe, 2019;25:113–27 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Luo XM, Edwards MR, Mu Q, Yu Y, Vieson MD, Reilly CM et al. Gut Microbiota in Human Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and a Mouse Model of Lupus. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2018;84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lopez P, de Paz B, Rodriguez-Carrio J, Hevia A, Sanchez B, Margolles A et al. Th17 responses and natural IgM antibodies are related to gut microbiota composition in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Sci Rep, 2016;6:24072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson BM, Gaudreau MC, Al-Gadban MM, Gudi R, Vasu C. Impact of dietary deviation on disease progression and gut microbiome composition in lupus-prone SNF1 mice. Clinical and experimental immunology, 2015;181:323–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med, 2009;1:6ra14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Edwards MR, Dai R, Heid B, Cecere TE, Khan D, Mu Q et al. Commercial rodent diets differentially regulate autoimmune glomerulonephritis, epigenetics and microbiota in MRL/lpr mice. Int Immunol, 2017;29:263–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sofi MH, Gudi R, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Johnson BM, Vasu C. pH of drinking water influences the composition of gut microbiome and type 1 diabetes incidence. Diabetes, 2014;63:632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tedeschi SK, Bermas B, Costenbader KH. Sexual disparities in the incidence and course of SLE and RA. Clin Immunol, 2013;149:211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fillmore PD, Blankenhorn EP, Zachary JF, Teuscher C. Adult gonadal hormones selectively regulate sexually dimorphic quantitative traits observed in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol, 2004;164:167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Libert C, Dejager L, Pinheiro I. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nature reviews Immunology, 2010;10:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Panchanathan R, Choubey D. Murine BAFF expression is up-regulated by estrogen and interferons: implications for sex bias in the development of autoimmunity. Mol Immunol, 2013;53:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Swanson CL, Wilson TJ, Strauch P, Colonna M, Pelanda R, Torres RM. Type I IFN enhances follicular B cell contribution to the T cell-independent antibody response. The Journal of experimental medicine, 2013;207:1485–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science, 2013;339:1084–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yurkovetskiy L, Burrows M, Khan AA, Graham L, Volchkov P, Becker L et al. Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity, 2013;39:400–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Walker SE, Besch-Williford CL, Keisler DH. Accelerated deaths from systemic lupus erythematosus in NZB x NZW F1 mice treated with the testosterone-blocking drug flutamide. J Lab Clin Med, 1994;124:401–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Roubinian JR, Papoian R, Talal N. Androgenic hormones modulate autoantibody responses and improve survival in murine lupus. The Journal of clinical investigation, 1977;59:1066–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maldonado MA, Kakkanaiah V, MacDonald GC, Chen F, Reap EA, Balish E et al. The role of environmental antigens in the spontaneous development of autoimmunity in MRL-lpr mice. Journal of immunology, 1999;162:6322–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Unni KK, Holley KE, McDuffie FC, Titus JL. Comparative study of NZB mice under germfree and conventional conditions. The Journal of rheumatology, 1975;2:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang H, Liao X, Sparks JB, Luo XM. Dynamics of gut microbiota in autoimmune lupus. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2014;80:7551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gaudreau MC, Johnson BM, Gudi R, Al-Gadban MM, Vasu C. Gender bias in lupus: does immune response initiated in the gut mucosa have a role? Clinical and experimental immunology, 2015;180:393–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gudi R, Perez N, Johnson BM, Sofi MH, Brown R, Quan S et al. Complex dietary polysaccharide modulates gut immune function and microbiota, and promotes protection from autoimmune diabetes. Immunology, 2019;157:70–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods, 2010;7:335–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wixon J, Kell D. The Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes--KEGG. Yeast, 2000;17:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Parks DH, Beiko RG. Identifying biologically relevant differences between metagenomic communities. Bioinformatics, 2010;26:715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, Cuervo A, Arboleya S, Duranti S et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. mBio, 2014;5:e01548–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dhariwal A, Chong J, Habib S, King IL, Agellon LB, Xia J. MicrobiomeAnalyst: a web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017;45:W180–W8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gavalchin J, Nicklas JA, Eastcott JW, Madaio MP, Stollar BD, Schwartz RS et al. Lupus prone (SWR x NZB)F1 mice produce potentially nephritogenic autoantibodies inherited from the normal SWR parent. Journal of immunology, 1985;134:885–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kalled SL, Cutler AH, Datta SK, Thomas DW. Anti-CD40 ligand antibody treatment of SNF1 mice with established nephritis: preservation of kidney function. Journal of immunology, 1998;160:2158–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Berghofer B, Frommer T, Haley G, Fink L, Bein G, Hackstein H. TLR7 ligands induce higher IFN-alpha production in females. Journal of immunology, 2006;177:2088–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nickerson KM, Christensen SR, Shupe J, Kashgarian M, Kim D, Elkon K et al. TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. Journal of immunology, 2010;184:1840–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee PY, Kumagai Y, Li Y, Takeuchi O, Yoshida H, Weinstein J et al. TLR7-dependent and FcgammaR-independent production of type I interferon in experimental mouse lupus. The Journal of experimental medicine, 2008;205:2995–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Umiker BR, Andersson S, Fernandez L, Korgaokar P, Larbi A, Pilichowska M et al. Dosage of X-linked Toll-like receptor 8 determines gender differences in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. European journal of immunology, 2014;44:1503–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liu Y, Seto NL, Carmona-Rivera C, Kaplan MJ. Accelerated model of lupus autoimmunity and vasculopathy driven by toll-like receptor 7/9 imbalance. Lupus Sci Med, 2018;5:e000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fish EN. The X-files in immunity: sex-based differences predispose immune responses. Nature reviews Immunology, 2008;8:737–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lockshin MD, Mary C Kirkland Center for Lupus Research. Biology of the sex and age distribution of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism, 2007;57:608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Barragan-Martinez C, Amaya-Amaya J, Pineda-Tamayo R, Mantilla RD, Castellanos-de la Hoz J, Bernal-Macias S et al. Gender differences in Latin-American patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Gender medicine, 2012;9:490–510 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Grimaldi CM. Sex and systemic lupus erythematosus: the role of the sex hormones estrogen and prolactin on the regulation of autoreactive B cells. Current opinion in rheumatology, 2006;18:456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Young NA, Wu LC, Burd CJ, Friedman AK, Kaffenberger BH, Rajaram MV et al. Estrogen modulation of endosome-associated toll-like receptor 8: an IFNalpha-independent mechanism of sex-bias in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol, 2014;151:66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Melez KA, Reeves JP, Steinberg AD. Modification of murine lupus by sex hormones. Annales d’immunologie, 1978;129 C:707–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ubeda C, Lipuma L, Gobourne A, Viale A, Leiner I, Equinda M et al. Familial transmission rather than defective innate immunity shapes the distinct intestinal microbiota of TLR-deficient mice. The Journal of experimental medicine, 2012;209:1445–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Putignani L, Del Chierico F, Petrucca A, Vernocchi P, Dallapiccola B. The human gut microbiota: a dynamic interplay with the host from birth to senescence settled during childhood. Pediatric research, 2014;76:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chervonsky AV. Microbiota and autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013;5:a007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rodriguez-Carrio J, Lopez P, Sanchez B, Gonzalez S, Gueimonde M, Margolles A et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis Is Associated with Altered Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Serum-Free Fatty Acids in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol, 2017;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rainsford KD, Parke AL, Clifford-Rashotte M, Kean WF. Therapy and pharmacological properties of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases. Inflammopharmacology, 2015;23:231–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Elkon KB, Wiedeman A. Type I IFN system in the development and manifestations of SLE. Current opinion in rheumatology, 2012;24:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pisitkun P, Ha HL, Wang H, Claudio E, Tivy CC, Zhou H et al. Interleukin-17 cytokines are critical in development of fatal lupus glomerulonephritis. Immunity, 2012;37:1104–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Amarilyo G, Lourenco EV, Shi FD, La Cava A. IL-17 promotes murine lupus. Journal of immunology, 2014;193:540–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Jackson SW, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Khim S, Schwartz MA, Li QZ et al. Opposing impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 signals on autoantibody repertoire and systemic inflammation. Journal of immunology, 2014;192:4525–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Murayama G, Furusawa N, Chiba A, Yamaji K, Tamura N, Miyake S. Enhanced IFN-alpha production is associated with increased TLR7 retention in the lysosomes of palasmacytoid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis research & therapy, 2017;19:234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sakata K, Nakayamada S, Miyazaki Y, Kubo S, Ishii A, Nakano K et al. Up-Regulation of TLR7-Mediated IFN-alpha Production by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol, 2018;9:1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mu Q, Tavella VJ, Kirby JL, Cecere TE, Chung M, Lee J et al. Antibiotics ameliorate lupus-like symptoms in mice. Sci Rep, 2017;7:13675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Jimenez-Jorge S, Molinero P, Rubio A, Guerrero JM, Osuna C. Treatment with testosterone or estradiol in melatonin treated females and males MRL/MpJ-Faslpr mice induces negative effects in developing systemic lupus erythematosus. J Pineal Res, 2008;45:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.