Naloxone is a safe and effective medicine for reversing the effects of opioid overdose. More than two decades ago, providers of health and harm-reduction services to people who inject opioids began equipping them with overdose-prevention information, skills—and vials of naloxone. Because naloxone is a prescription drug, state laws created uncertainties about the circumstances under which lay persons could be provided with naloxone to administer in case of an overdose.1 Harm reductionists found ways to proceed without law reform,2 but removing legal barriers became increasingly important to diffusing and scaling these programs.

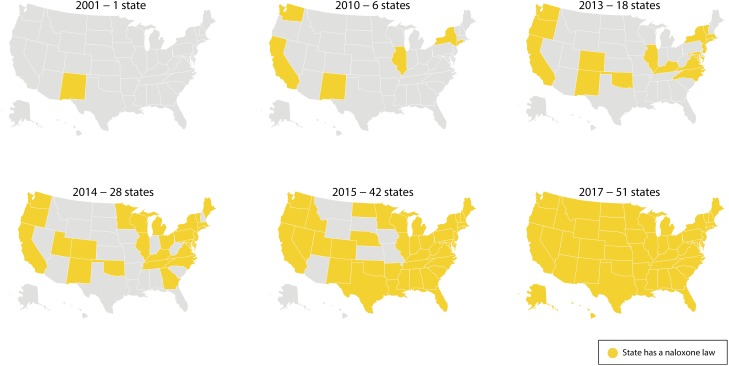

New Mexico was the first state to legislate a path to lay administration. Its system, followed in some of the other early acting states, required extensive training and documentation for lay administration. Slowly—painfully slowly—more states started to knock down prescription and medical practice law barriers to naloxone as a death-preventing intervention. As late as 2010, only six states had acted (Figure 1). As the country and its policymakers finally awoke to the severity of the overdose problem, more states enacted naloxone laws, which became increasingly simple, moving away from elaborate training schemes and eventually to the widespread adoption of standing-order models. By 2017, every state had enacted a naloxone access law, and, as reported by Green et al. (p. 881) in this issue of AJPH, some states had started requiring coprescription of naloxone with opioids to patients at increased risk of overdose.

FIGURE 1—

State Adoption of a Law Governing Law Administration of Naloxone, 2001–2017.

Source. Prescription Drug Abuse Policy Systems, http://www.pdaps.org (laws in effect as of December 31 of each year).

The study by Green et al. is important for both its findings and what the article represents in terms of the relationship between policymaking, epidemiology, and legal epidemiology. The article credibly reports an association between the implementation date of coprescribing laws and 90-day changes in prescribing patterns, an association that under the circumstances supports a provisional inference of causation for policymaking purposes. It seems reasonable to assume that these laws expand the pool of providers who are prescribing naloxone and get naloxone to at-risk people in more places.

The article is also important in what it stands for: timely evaluation of the health effects of legal interventions. This article is a first look, initiated within a year or two of the emergence of a new legal approach and analyzing accessible indicators in early adopting states. It lays the groundwork for more rigorous and ambitious studies comparing more data points in more states over more time, and ideally assessing not just the effect of one naloxone intervention law but the set of specific provisions that promote naloxone access through standing orders, first responder use, and syringe exchange programs. Research is also needed to answer such key questions as how coprescribing influences or is influenced by the stigma of drug use, whether prescribers prescribe lower doses to avoid triggering the requirement, and whether coprescribing increases overdose awareness and prevention efficacy among caregivers of the recipient.

Alas, we can’t be confident that those studies will follow, and in this respect the article and the legal reform of naloxone access stand as a good example of the failure of our health research establishment to devote sufficient attention and resources to the timely evaluation of law as a factor in public health and a mechanism for scaling successful interventions. New Mexico’s 2001 naloxone law, which introduced a novel scheme to address its high overdose mortality rate, was, as far as I can tell, never evaluated in a published, peer-reviewed study. As a few other states adopted their own legal models, early studies of lay overdose training with naloxone provision began to appear, but as late as 2014 a systematic review found only 19 studies of overdose prevention programs, none of which focused on the legal mechanisms.3 This was consistent with a general lack of intensive research attention to the slew of policy interventions states were by then launching to address overdose.4 What claims to be, and as far as I am aware is, the first published, peer-reviewed study of the impact of naloxone laws on overdose did not appear until 2018.5

Research can and does do better, as the experience evaluating the effects of legal interventions in high-profile areas such as tobacco control, alcohol, and motor-vehicle safety show.6 Such work has been the exception rather than the rule, however. National Institutes of Health funding for studying the health effects of law has been tiny compared with the need for research to guide important policy interventions.7 More often, law is allowed to unfold as if it were weather, impervious to systematic management and ultimately too complex to fully understand. The results are various but unfortunate: laws that don’t actually work are nonetheless perceived as “solutions” and forestall the development of better interventions, effective laws are not identified and widely adopted, and harmful side effects are not detected.

A powerful estimate of the costs of slow and uneven evaluation is cited by Green et al. In a modeling study published in these pages two years ago, Pitt et al. (https://bit.ly/2RqWQa3) estimated the net effects of 11 policies on 10-year mortality from opioid overdose. Naloxone and needle exchange, for example, were predicted to save lives, but several interventions, including prescription drug–monitoring programs and rescheduling certain opioids, were predicted to kill more than they saved. The prediction about prescription drug–monitoring programs is particularly striking in the context of a more thorough evaluation of health policies, because, studied in isolation, prescription drug–monitoring programs’ negative impact on prescribing has been seen as a public health success.

A better approach for opioids would have been more like the approach to road safety, for which policy was developed, rolled out, and evaluated more systematically.6 Efforts like New Mexico’s would have been evaluated right away, as would the alternative approaches that emerged in the next few years. By 2010, we could have had rigorous multistate comparative data and thorough implementation data that could have guided—and sped up—policy adoption in other states. New ideas such as standing orders and coprescription might have moved more quickly onto the evolving policy agenda. The answers to important questions of implementation and effectiveness, like the apparently limited impact of Good Samaritan laws, would be better illuminated by more rigorous data.

Law has been a central element of the response to overdose, but after nearly 20 years it is hard to say which laws are helping and which are causing harm. Green et al. have offered evidence that coprescription is promising, but other potentially more promising policy changes to get the antidote into the hands of those most at risk—notably moving naloxone to over-the-counter status—seem to be stagnating. We can do better.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work on this editorial was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; grant 77249).

The author thanks Elizabeth Platt and Bethany Saxon for assistance in preparing this editorial.

Note. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of RWJF.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

See also Green et al., p. 881.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burris S, Norland J, Edlin BR. Legal aspects of providing naloxone to heroin users in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2001;12(3):237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(6):101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(3):153–163. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, Jones CM. What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burris S, Anderson E. Legal regulation of health-related behavior: a half century of public health law research. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. 2013;9:95–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim JK, Sorensen AA, Grunwald H, Burris S. Supporting a culture of evidence-based policy: federal funding for public health law evaluation research, 1985–2014. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(6):658–666. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]