Abstract

Objectives. To compare the association of California Proposition 56 (Prop 56), which increased the cigarette tax by $2 per pack beginning on April 1, 2017, with smoking behavior among low- and high-income adults.

Methods. Drawing on a sample of 17 206 low-income and 21 324 high-income adults aged 21 years or older from the 2012 to 2018 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data, we explored 2 outcomes: current smoking prevalence and smoking intensity (average number of cigarettes per day among current smokers). For each income group, we estimated a multivariable logistic regression to analyze the association of Prop 56 with smoking prevalence and a multivariable linear regression to analyze the association of Prop 56 with smoking intensity.

Results. Although we observed no association between smoking intensity and Prop 56, we found a statistically significant decline in smoking prevalence among low-income adults following Prop 56. No such association was found among the high-income group.

Conclusions. Given that low-income Californians smoke cigarettes at greater rates than those with higher incomes, our results provide evidence that Prop 56 is likely to reduce income disparities in cigarette smoking in California.

In 1989, California initiated the first and longest-running comprehensive tobacco control program in the United States.1,2 Between 1988 and 2018, per capita cigarette consumption declined by more than 80%1; however, income disparities remain. In 2016 to 2017, adult smoking prevalence among those with income less than 100% federal poverty level was 15.8% in California; smoking prevalence among those with income 300% federal poverty level or greater was 7.7%.1

In November 2016, California voters approved the California Healthcare, Research and Prevention Tobacco Tax Act (Proposition 56; Prop 56), increasing the excise tax on cigarettes by $2 per pack. Prop 56 was implemented on April 1, 2017. A voluminous literature indicates the effectiveness of tax increases in reducing smoking.3,4 We compared the association of Prop 56 with smoking prevalence and intensity among low- and high-income Californians immediately following implementation, exploring how Prop 56 influenced income disparities in smoking. To our knowledge, this work offers the first glimpse of changes in smoking behaviors following Prop 56.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the 2012 to 2018 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a statewide, cross-sectional survey of adults aged 18 years or older.1,5 The data include detailed information on cigarette smoking behavior.1,5 This study focused on low- and high-income adults aged 21 years or older, defined as those with annual household incomes of $24 999 or less and more than $75 000 (28.4% and 37.8% of the entire sample, respectively). Because California’s Tobacco 21 law raised the minimum age for tobacco sales from 18 to 21 years effective June 9, 2016, we excluded respondents younger than 21 years. The initial sample included 19 455 low-income and 24 261 high-income adults. After excluding those with missing values for the smoking behavior measures (8.2% and 5.0% of the low- and high-income respondents, respectively) and sociodemographic variables (another 3.7% and 7.7% of the low- and high-income respondents, respectively), our final study sample included 17 206 low-income and 21 324 high-income adults; 3910 low-income and 1238 high-income adults were interviewed after implementation.

We examined 2 outcomes: current smoking status (smoked 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and currently smoke every day or some days) and, among current smokers, smoking intensity (average number of cigarettes per day). The Shapiro-Wilk test rejected the null hypothesis that the cigarettes per day variable was normally distributed. To address the skewed distribution, we logarithmically transformed the cigarettes per day variable, a widely used and accepted approach.6

Our primary covariate was a dichotomous Prop 56 indicator, reflecting preimplementation and postimplementation of Prop 56 on April 1, 2017. Other covariates included gender (male and female), age (21–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥ 65 years), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic other), education (< high school education, high school graduate, some college, and college degree and higher), marital status (married, unmarried couple, divorced/widowed/separated, and never married), employment status (employed, unemployed, and not in labor force), and, to account for secular time trends, survey year.

For each income group, we used a multivariable logistic regression to estimate the association of Prop 56 with the likelihood of current smoking, controlling for all other covariates. In the smoking intensity analysis, we estimated log-transformed cigarettes per day as a function of Prop 56 and all other covariates with a linear regression. We estimated analyses separately for the low- and high-income groups and for the larger, combined sample of both income groups. The combined analysis introduced a low-income status dummy and an interaction term between this dummy and the Prop 56 indicator. We conducted a sensitivity analysis, estimating the aforementioned regressions with modified income groups, splitting the full study sample at the approximate median: lower-income and higher-income groups were defined as those with income lower than $50 000 per year (48.5% of the entire sample) and $50 000 or more per year, respectively.7 All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and incorporated California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey weights to account for complex survey design.

RESULTS

Smoking prevalence among low-income adults declined over the Prop 56 preimplementation to postimplementation period (from 15.2% to 11.3%; P < .001), whereas high-income adults experienced a small but not statistically significant increase in smoking prevalence (5.7% to 5.9%; P = .78). The average number of cigarettes per day decreased over this period among the low-income (8.9 to 8.2 cigarettes; P = .26) and high-income (9.0 to 6.8 cigarettes; P < .05) groups, although the decrease among the low-income group was not significant. Detailed descriptive analyses results are available in Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

After we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and time trends, regression results (Tables B and C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) highlighted a negative association between Prop 56 and smoking prevalence for the low-income group (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.34, 0.60); no such association was found within the high-income group or combined sample of both income groups. The interaction term in the smoking prevalence analysis among the combined sample was significant (AOR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.45, 0.90), indicating that the Prop 56 preimplementation to postimplementation period changes in smoking prevalence differed between low- and high-income adults. Prop 56 was not significantly associated with smoking intensity for either income group. The sensitivity analysis showed similar results (Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) except that the preimplementation to postimplementation changes in smoking prevalence were not significantly different between the lower- and higher-income groups when the modified income thresholds were used.

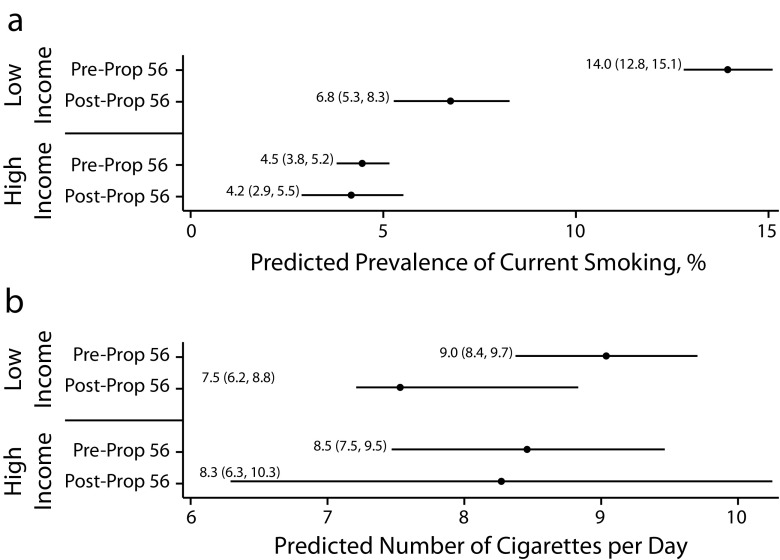

Figure 1 presents the predicted values of smoking prevalence and intensity holding other covariates at the mean. For the low-income group, predicted prevalence of current smoking differed significantly between the Prop 56 preimplementation and the postimplementation period, indicating a statistically significant marginal effect of Prop 56 on smoking prevalence. This association was not observed among the high-income group. The marginal effect of Prop 56 on smoking intensity was not significant for either income group.

FIGURE 1—

Marginal Effects of California Proposition 56 (Prop 56) as Exhibited by Comparing the Prop 56 Preimplementation and Postimplementation Period by Income Group and (a) Predicted Prevalence of Current Smoking and (b) Predicted Number of Cigarettes per Day: California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2012–2018

DISCUSSION

A voluminous literature establishes the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases in reducing smoking.3,4 Several studies examining smoking prevalence found that lower-income individuals were more price responsive compared with higher-income groups,7–9 whereas other studies found no evidence of differences.10,11

The Tobacco 21 law was implemented in California during the study period. We addressed this by excluding adults younger than 21 years. Future work is needed to investigate whether differential associations exist between Prop 56 and smoking behavior by age and race/ethnicity; nevertheless, our study provides further evidence that low-income adults may be more responsive than higher-income groups in reducing smoking prevalence following a large cigarette tax increase.

Between 1989 and 2008, California’s comprehensive tobacco control program reduced health care costs in the state by $134 billion12; however, these gains are not shared equally among all income groups. In particular, low-income Californians continue to smoke at relatively higher rates. A multivariable regression analysis based on data from the same period found that smoking prevalence among all Californians aged 21 years or older declined from 10.4% before Prop 56 to 8.4% after Prop 56. That declining trend was statistically significant (Table B) and was likely driven by reductions in smoking prevalence among low-income adults. The observed decrease in smoking prevalence among low-income individuals immediately following implementation provides evidence that Prop 56 is likely to reduce income disparities in cigarette consumption.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Low-income individuals smoke at higher rates in California compared with higher-income groups1 and have disproportionally higher rates of tobacco-related disease.2,3 Our results indicate that Prop 56 was associated with an immediate reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking among the low-income sample, suggesting possible long-term improvements in reducing the income disparities in tobacco-related disease burden. Although this was an observational study, making claims of causality difficult, the findings offer evidence of the potential positive effects of taxation on improving health equity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (grant TRDRP 28IR-0041).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because we conducted a statistical analysis of secondary data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vuong TD, Zhang X, Roeseler A. California Tobacco Facts and Figures 2019. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health; May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roeseler A, Burns D. The quarter that changed the world. Tob Control. 2010;19(suppl 1):i3–i15. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs — 2014. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control: IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention in Tobacco Control. Vol 14. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Survey Data & Documentation. August 8, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/index.htm. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- 6.Yao T, Ong MK, Max W et al. Responsiveness to cigarette prices by different racial/ethnic groups of US adults. Tob Control. 2018;27(3):301–309. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Response to increases in cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups—United States, 1976-1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(29):605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colman G, Remler D. Vertical equity consequences of very high cigarette tax increases: if the poor are the ones smoking, how could cigarette tax increases be progressive? J Policy Anal Manage. 2008;27(2):376–400. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker JM, Watson KA. The consequences of high cigarette excise taxes for low-income smokers. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks P, Jerant AF, Leigh JP et al. Cigarette prices, smoking, and the poor: implications of recent trends. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1873–1877. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borren P, Sutton M. Are increases in cigarette taxation regressive? Health Econ. 1992;1(4):245–253. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730010406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. The effect of the California tobacco control program on smoking prevalence, cigarette consumption, and healthcare costs: 1989–2008. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e47145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]