Abstract

Objectives. To describe the evolution of flavored e-cigarette sales since the expansion of the JUUL brand, and to describe the effect of JUUL’s November 2018 decision to self-regulate the flavors it sold in stores on flavored e-cigarette sales.

Methods. We used Scantrack data on sales of e-cigarettes in the United States from January 2015 to October 2019 provided by The Nielsen Company. National sales values were aggregated monthly in 5 flavor categories (fruit, menthol/mint, sweet, tobacco, and other).

Results. The expansion of JUUL sales coincided with an expansion in fruit-flavor sales through October 2018. Once JUUL withdrew fruit and sweet flavors from stores, menthol/mint came to dominate the e-cigarette market, but through 2019, a new surge in fruit-flavor sales by non-JUUL brands was observed.

Conclusions. After a decline in sales following JUUL’s decision to withdraw some flavored products from stores, JUUL sales recovered within weeks and surpassed their previous maximum in those same channels, as consumption shifted to the menthol/mint and tobacco flavors that remained on shelves.

Public Health Implications. These trends suggest shortcomings of self-regulation and highlight the utility of government regulation.

E-cigarette use among US youths has dramatically increased over the past 2 years, which has been circumstantially tied to the presence of flavored e-cigarette products in the marketplace.1 Given the association between flavored e-cigarettes and youth initiation,2 little is known about the trends in sales of flavored e-cigarettes since 2016—a period in which a shift in the market also occurred, driven by the rapid growth of JUUL Labs toward small, rechargeable e-cigarettes that heat cartridges containing concentrated nicotine salt liquids.3 Previous studies found that use of nontobacco or menthol-flavored e-cigarettes had increased—up to 56.4% of e-cigarette unit sales in December 20164—but little is known about how the rise of JUUL affected sales of flavored e-cigarettes thereafter. In addition, data describing the effects of industry self-regulation of flavored product availability are lacking.

This study addressed these gaps by examining trends in sales of flavored e-cigarettes from January 2015 through October 2019 to characterize types of flavors and the effects of JUUL removing some flavors from store shelves.

METHODS

We used Scantrack data on sales of e-cigarettes in the United States provided by The Nielsen Company. The data set contains UPC-level sales of e-cigarettes split into dollar and unit volumes at 4-week increments in Nielsen-tracked channels (convenience, food, and drug stores), which were aggregated to the national level. Although Nielsen Scantrack covered only about 24% of all US e-cigarette sales in 2016, by 2019, the data set covered about 70% of all US e-cigarette sales.5 That figure compares the value of all e-cigarette sales in the Nielsen data with the value of all e-cigarette sales as calculated by market research firm ECigIntelligence, which combines estimates of the number of e-cigarette users with an estimated per-capita annual expenditure on products to arrive at the full market size. Dollar sales data were aggregated to the national level under 5 brands (JUUL, NJOY, blu, VUSE, Logic, and other) and 5 flavor categories (fruit, menthol/mint [which are not clearly separable in the data set], sweet [nonfruit candy or dessert flavors], tobacco, and other [including variety packs]). Sales of products without e-liquid were excluded. Figures were adjusted for inflation by using August 2019 as the base. We report “shares” or proportions of each flavor category over time among total e-cigarette sales.

RESULTS

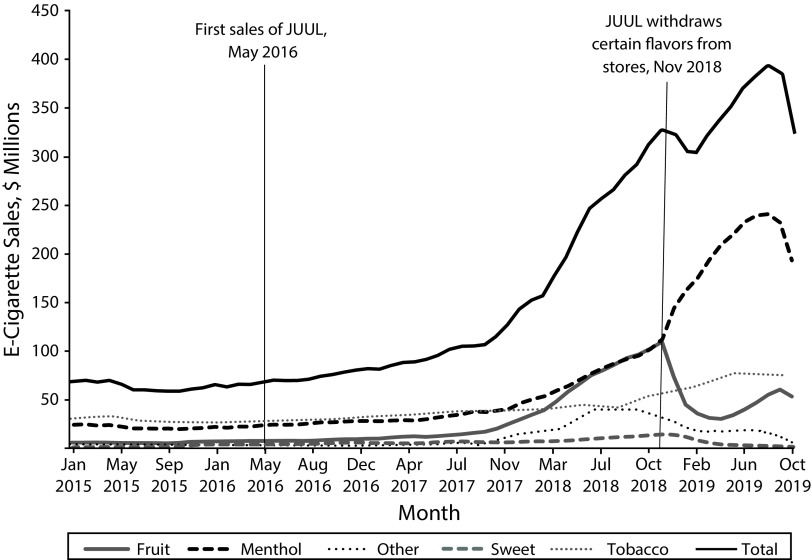

Figure 1 shows that during 2015 and 2016, e-cigarette flavor shares remained relatively steady. As JUUL sales grew from 2017 through 2018,6 we observed a concurrent increase in the share of fruit-flavored e-cigarettes in Nielsen-tracked channels, rising from 12.9% of sales ($10 161 000 per month) in January 2017 to 33.3% of sales ($96 486 000) in October 2018. Fruit briefly exceeded menthol/mint as the flavor category with the largest proportion of sales in October 2018. This increase in fruit share was matched by a decline in tobacco share from 39.7% of sales in January 2017 to 16.6% of sales in October 2018. Late 2018 also marked the peak of sweet sales at $14 093 000 in December 2018, whereas sales of other (notably, JUUL’s cucumber flavor) peaked at $38 336 000 in July 2018.

FIGURE 1—

Monthly US E-Cigarette Sales by Flavor: January 2015–October 2019

Note. Figures have been inflation adjusted to August 2019 dollars. Data exclude hardware.

Source. Authors’ own calculations based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Scantrack Service for the e-cigarette category for January 2015 through October 2019 for the Nielsen-defined eXtended All Other Channels (xAOC) and Convenience Metro Markets. Copyright 2019, The Nielsen Company.

In November 2018, under pressure from the US Food and Drug Administration to curb rising youth vaping rates,7 JUUL removed most of their flavored products, excluding tobacco, menthol, and mint flavors, from retail stores but not their Web site.8 This precipitated a decline in sales of fruit-flavored products to 9.1% ($30 494 000) by April 2019. During this period, the share of menthol/mint flavor spiked from 33.0% to 62.5% ($95 592 000 to $209 567 000), and the share of tobacco flavor rose from 16.6% to 22.3% ($48 038 000 to $74 789 000). JUUL captured 91% of the growth in tobacco and all of the growth in menthol/mint as sales of non-JUUL menthol/mint declined over that period. However, fruit-flavor sales began to increase again to 15.8% ($60 594 000) by September 2019, largely on the expanding sales of the NJOY brand whose monthly fruit-flavor sales increased from September 2018 to September 2019 by $37 450 000.

DISCUSSION

JUUL Labs’ November 2018 decision to withdraw products from stores that were not flavored to taste like tobacco, menthol, or mint shifted the flavors being purchased by e-cigarette users in a short time. JUUL’s initial growth precipitated the well-documented phenomenon of the use of novel fruit and sweet flavors among youth nonsmokers.8 After a brief decline in JUUL sales following their decision to withdraw some flavored products from most retail channels, JUUL sales recovered and surpassed their previous maximum in those same channels within 12 weeks as JUUL consumption shifted marginally toward the tobacco and heavily toward the menthol/mint flavors that remained on shelves.

Notably, e-cigarette sales in the Nielsen data peaked in August 2019 at $441 million per month (inclusive of hardware). It is too soon to determine why sales slowed, but plausible explanations include consumers’ reactions to media reports detailing the outbreak of vaping-related illnesses and announcements of forthcoming bans on the sales of all or some e-cigarettes by the governors of several states and the president of the United States.9 Because US federal guidance on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes has focused on a narrow prohibition on the sale of flavors other than tobacco or menthol in cartridge-based devices like JUUL10 and vaping-related illnesses have been connected to illicit tetrahydrocannabinol vaping devices,11 it remains to be seen how US e-cigarette sales will change in reaction to these external shocks.

Our findings were subject to limitations. We could not disentangle here whether JUUL’s growth was driven by the presence of these appealing flavors or whether the relationship worked in the other direction and was spurred by JUUL’s powerful nicotine delivery ability or a combination of these factors. In addition, because Nielsen data cover only traditional brick-and-mortar retailers, our findings did not include e-cigarette sales taking place online, where flavored JUUL products were available until October 2019,7 or in vape shops. Trends in traditional brick-and-mortar store sales have particular relevance to youth accessibility because they constitute a core source of supply to the youth population, both through direct purchase and through indirect or informal transfers from older students to their younger peers.12

These trends suggest that self-regulation has a high likelihood of being inadequate to meet the interests of public health, because JUUL’s withdrawal of fruit-flavored products was quickly offset by a combination of increased fruit-flavored sales by JUUL’s competitors and increased sales of other JUUL flavors—notably, mint/menthol—with demonstrable appeal to youths.8 Given the insubstantial net effect of JUUL’s limited withdrawal in the very channels from which JUUL withdrew, it appears that self-regulation did not advance the public health goal of reducing youth vaping in this case. In contrast with government regulations setting consistent standards that all companies must meet, self-regulation enables companies to select rules that are either unlikely to disrupt their own business or likely to incentivize smaller competitors to fill in the void, or both. The results suggest that e-cigarette users facing partial bans substituted other flavors or brands, indicating that poorly originated government regulation also may cause unintended consequences. For example, banning certain flavored products in limited retail channels or devices may cause shifts to unaffected channels and devices. Future research should address interactions between e-cigarette product regulation and market trajectories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

American Cancer Society provided the funding to purchase the data required for this analysis.

The conclusions drawn from the Nielsen data are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Nielsen. Nielsen was not responsible for and had no role in analyzing and preparing the results.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Meernik C, Baker HM, Kowitt SD, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Impact of non-menthol flavours in e-cigarettes on perceptions and use: an updated systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031598. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leventhal AM, Goldenson NI, Cho J et al. Flavored e-cigarette use and progression of vaping in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20190789. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):146–151. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuiper NM, Loomis BR, Falvey KT et al. Trends in unit sales of flavored and menthol electronic cigarettes in the United States, 2012-2016. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E105–E105. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ECigIntelligence. Key global e-cigarette markets database: October 2019. October 31, 2019. Available at: https://ecigintelligence.com/key-global-e-cigarette-markets-database. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- 6.Herzog B, Kanada P. Nielsen: tobacco all channel data thru 5/18 - cig vol declines strengthen. May 30, 2019. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/uq8g6hn. Accessed May 30, 2019.

- 7.Ho C. Under FDA pressure, Juul to halt sale of flavored e-cigarette products in stores. San Francisco Chronicle. November 13, 2018. Available at: https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Under-FDA-pressure-Juul-to-halt-sale-of-flavored-13388486.php. Accessed February 26, 2020.

- 8.Leventhal AM, Miech R, Barrington-Trimis J, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME. Flavors of e-cigarettes used by youths in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2132–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott B, Maloney J. Vaping bans raise fear of return to smoking. Wall Street Journal. October 25, 2019. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/vaping-bans-raise-fear-of-return-to-smoking-11572013353. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint [press release]. January 2, 2020. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 11.Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury — United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(3):90–94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu ST, Snyder K, Tynan MA, Wang TW. Youth access to tobacco products in the United States, 2016-2018. Tob Regul Sci. 2019;5(6):491–501. doi: 10.18001/TRS.5.6.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]