Abstract

Continued improvements in HPLC have led to faster and more efficient separations than previously possible. One important aspect of these improvements has been the increase in instrument operating pressure and the advent of ultrahigh pressure LC (UHPLC). Commercial instrumentation is now capable of up to ~20 kpsi, allowing fast and efficient separations with 5–15 cm columns packed with sub-2 μm particles. Home-built instruments have demonstrated the benefits of even further increases in instrument pressure. The focus of this review is on recent advancements and applications in liquid chromatography above 20 kpsi. We outline the theory and advantages of higher pressure and discuss instrument hardware and design capable of withstanding 20 kpsi or greater. We also overview column packing procedures and stationary phase considerations for HPLC above 20 kpsi, and lastly highlight a few recent applicatioob pressure instruments for the analysis of complex mixtures.

Keywords: Ultrahigh pressure LC, Column packing, Small particles, Long columns, Omics

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical advantages of higher pressure

Pressure can ultimately be a limiting factor for improvements in separation speed and efficiency when using packed columns. It is well known that implementing smaller diameter stationary phase particles can improve separation efficiency by decreasing band broadening due to eddy diffusion and resistance to mass transfer [1,2]. To maintain a given column length, however, much higher back pressure is required to push solvent through a tube packed with such small particles because the pressure requirement is proportional to the square of particle diameter (dp). Additionally, because smaller particles reduce band broadening from mass transfer, the optimum mobile phase velocity, uopt, is proportional to dp. Taken together, the optimum pressure (e.g. pressure required to reach hmin) is proportional to the cube of the particle diameter.

Kinetic plots are helpful in identifying conditions that give a desired performance (theoretical plates (N) or peak capacity for gradient analysis) based on dp, pressure limit, and analysis time. Such plots therefore can help to understand when higher pressures are beneficial and should be implemented [3,4]. Fig. 1 shows a kinetic plot displaying the plate time (time it takes to obtain 1 plate) versus plates for two different particle sizes (0.5 μm and 1.7 μm) and instrument pressure limits (12 kpsi and 50 kpsi). Going from left to right along a curve, column length increases such that dead time and column efficiency are increased. Column dead times are projected as a diagonal line for clarity. From Fig. 1, it is clear how higher instrument pressure can lead to faster separations for a given plate number or higher plate numbers in a given time. For example, plate numbers for a 30 s dead time increase from 35,000 to 88,000 with 0.5 μm particles when 50 kpsi is available compared to 12 kpsi (green versus blue trace). When 1.7 μm particles are used, a more modest increase from 30,000 to 38,000 is achieved from 12 to 50 kpsi and a dead time of 30 s. However, at longer analysis times, e.g. 180 s, 1.7 μm particles are beneficial over 0.5 μm when 50 kpsi is available (blue vs. black trace). Thus, while higher pressures are almost always beneficial when column length or particle size can be varied, the extent of these improvements can vary. Careful consideration of particle size and column length with the desired analysis time and plate count must be done to take advantage of higher pressure.

Fig. 1.

Kinetic plot illustrating the effect of pressure, particle size, and analysis time on separation efficiency using packed column liquid chromatography. The blue and green traces are what is achievable with 0.5 μm particles at 50 and 12 kpsi, respectively. The black and orange traces are what is achievable with 1.7 μm particles at 50 and 12 kpsi, respectively. Different column dead times are shown as diagonal lines for clarity.

1.2. Frictional heating effects

Although ultrahigh pressures can open new opportunities in performance, several practical issues must be met as well. With higher operating pressures and flow rates, frictional heating can promote temperature gradients within the column and hurt column performance, thus negating potential benefits [5]. Consequently, capillary columns with inner diameters between 10 and 150 μm have typically been used to allow rapid dissipation of the heat that is generated [6]. The use of “micro-bore” columns of 1.5 mm i.d. packed with 1–1.5 μm particles were operated up to 20 kpsi with no apparent efficiency losses [7–9]. However, recent studies on 2.1 mm i.d. columns operated up to 38 kpsi showed dramatic temperature increases (up to 60°C) relative to the inlet temperature, significantly contributing to a higher plate height [10]. Although different column environments and particle types can alter the extent of viscous heating and its effect on separation efficiency [11,12], it is likely that capillaries and possibly narrow-bore (e.g. 1 mm i.d.) columns will remain the dominant format for operation above 20 kpsi. A recent review on the potential for higher pressures (up to 44,000 psi) in analytical scale column formats further discusses frictional heating effects and other considerations [13].

1.3. Extra column effects

Higher performance also requires careful attention to extra column dead volumes in order to maintain separation efficiency [14]. A few recent reports using commercial instrumentation studying the effect of extra column dead volume on separation performance will be highlighted here and should be considered when operating above 20 kpsi to achieve the expected performance (e.g. from kinetic plot data). In one study, for example, dead volume from the injector alone led to a 130% increase in plate height for a non-retained analyte [15]. Separation efficiency loss due to injection dead volume is dependent on a number of other variables, including flow rate, column length and column inner diameter [16]. Commercial capillary instrumentation continues to improve in terms of system dispersion; however, even state-of-the-art instrumentation has been shown to limit high efficiency columns, with one report indicating peak widths that are ten times larger when considering extra column volume contributions such as autosampler injection and detection [17]. Home-made injectors that provide narrow injection bands on column have been reported and are discussed more in section 2.1 [18].

Band broadening from connection tubing and the detector can also be problematic. Pre-column broadening can often be minimized by analyte focusing at the head of the column, using either solvent or temperature based approaches [19,20]. Broadening due to post-column tubing and detector hardware, however, is more difficult to eliminate and can cause losses in separation performance [21,22]. On-column detection are popular approaches for eliminating post column broadening and obtaining accurate column plate count measurements [23,24]; however, these techniques are typically less robust than commercial detectors and require high operator skill. Post-column refocusing to maintain separation performance and increase detection sensitivity is of interest. A recent example of solvent-based post-column refocusing achieved a 17.3 enhancement factor when injecting 2 μL peaks [25]. For mass spectrometry (MS) detection, an attractive avenue for eliminating post-column dead volume is to pack columns with an embedded electrospray tip such that the packed bed extends to the end of the spray tip. Lastly, using larger analytical scale columns (e.g. 1–4.6 mm i.d.) is another approach for limiting the influence of extra column volume on separation efficiency due to the larger peak volumes. However, in addition to the heating effects discussed above, extra column effects are still an issue with these larger columns [13,26].

2. Hardware for over 20 kpsi

2.1. Isocratic systems

Many researchers have reported injection systems able to withstand very high inlet pressures, with some reports of over 100 kpsi [6,18]. Many of these systems are built around stainless steel valves and tubing that are commercially available, for example from High Pressure (HiP) equipment company. These injection systems typically employ a static-split flow injection scheme. While these injectors offer very narrow injection bands that are good for column evaluation under isocratic conditions, they often require manual manipulation of valves and waste sample [18]. An air actuated needle valve injection system has also been reported that is automated and offers 200 nL injection volumes capable of operating up to 40 kpsi [7].

2.2. Gradient systems

Although isocratic systems are useful for testing columns and some applications, it will be necessary to have reliable and automated gradient elution capability at ultrahigh pressure to realize the capabilities suggested by the kinetic plot in Fig. 1. Early ultrahigh pressure gradient systems were capable of operating up to 70 kpsi but had notable shortcomings, including split-flow [27,28], nonlinear gradients [28,29], and lack of automation [28]. Further improvements in system design (e.g. Refs. [30–32]) have allowed for automated sample injection and operation up to 45 kpsi with splitless and linear gradients. A comparison of two systems is shown in Fig. 2A and B. The system in Fig. 2A used a solvent reservoir filled with weak solvent and pushed strong solvent through the system to perform the separation. The system required manual operation, produced nonlinear gradients due to exponential dilution, and necessitated splitting the flow over 100-fold. The system in Fig. 2B was fully automated, produced linear gradients, and did not require split flow. The system used a commercial LC to load the gradient and inject sample on to a storage loop, followed by ultrahigh pressure separation using a second, independent pneumatic amplifier pump. A similar design was also implemented for narrow bore (2.1 mm) columns [32]. Many of these systems operate at constant pressure rather than constant flow, which can be beneficial as the flow is not limited by the highest viscosity in the gradient, thus decreasing analysis time without sacrificing peak capacity [33].

Fig. 2.

Schematic of different gradient instrument designs (A and B). Design A is from Ref. [28] and operable up to 70 kpsi, however lacked automation, produced nonlinear gradients, and required flow splitting to produce nanoliter per minute flow rates. Design B is from Ref. [30] and is fully automated, splitless, and produces linear gradients. Gradient loading and sample injection are performed with a commercial UPLC and stored on a gradient loop, with subsequent ultrahigh pressure separation performed with a pneumatic amplifier pump. The pressure limit was ~45 kpsi. Illustrations of the fittings for each design (C and D) show differences in bolt size and tubing connection leading to the differences in pressure limit of the two systems. Adapted with permission from Refs. [28,30]. Copyright (1999) American Chemical Society.

Critical to both isocratic and gradient systems are valves and fittings that do not leak at ultrahigh pressure and have minimal dead volume. For capillary systems, freeze/thaw valves are an attractive approach as opposed to mechanical valves as they are inherently zero dead volume, do not clog, and hold at pressures of at least 60 kpsi (Fig. 2B) [30,34]. Mechanical needle valves are still quite common and are typically made from stainless steel. These valves however often require special bolts and fittings to withstand higher pressures and are more prone to clogging or leaking. Manufacturing and implementing fittings for capillaries are difficult practices. While providing low dead volume (estimated around 150 nL) and amenable to full automation, the fittings used in Ref. [30] leaked above ~ 30 kpsi, whereas the fittings used in Ref. [28] were reliable up to 70 kpsi. This difference is likely due to the different sizes of nuts and bolts that were used and soldering of the tubing compared to a small stainless steel collet to hold the capillary (Fig. 2C and D). Thus, fittings are a main bottleneck for further pushing the operating pressure of LC, as pneumatic pumps and larger i.d. tubing (e.g. from High Pressure Co.) are capable of operation up to 150 kpsi.

3. Column packing

UHPLC is most useful when small to medium (e.g. 1.7–3 μm) sized stationary phase particles are packed into long columns (~30–200 cm), or very small particles (e.g. 0.5–1.7 μm) are packed into shorter columns (typically < 20 cm). These advantages were illustrated in the kinetic plot in Fig. 1; however, equal quality of packing is assumed when creating these plots, which is not always the case when moving to smaller particles and/or longer columns. In this section we summarize packing techniques and conditions used to pack various particle types and sizes. Notable results are listed in Table 1, while recent reports and future directions for column packing are discussed.

Table 1.

Summary of reports on different column packing techniques and conditions for UHPLC separations. Analysis time (t0) is estimated or not shown for work that focused primarily on packing quality.

| Packing Technique | Operating Pressure (kpsi) | Particle Type | Slurry Compositiona | Column Dimensions | Platesb | hmin | Time (t0)c | Novel Aspect of Work | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centripetal forces | n/a (CEC used) | 3 μm, porous C18 | 20–50 mg/mL in methanol | 20 cm × 75 μm | 48,000 | 1.5 | 2 min | Packing by centripetal forces | [36] |

| Supercritical CO2 | 40 | 1.5 μm, nonporous C6 | 40 mg/mL in isopropanol | 12–33 cm × 29 μm | 190,000 | 1.3 | 0.5 min | Fast UHPLC with ToF-MS | [24] |

| Slurry Pressure | 60 | 1.5 μm, nonporous C18 | n/a; in 33% acetone/67% hexane | 66 cm × 30 μm | 300,000 | 1.4 | 2.5 min | Isocratic LC at 60 kpsi for first time | [23] |

| Slurry Pressure | 20 | 1.4–3 μm, porous C18 | n/a; in 90% acetonitrile | 40–200 cm × 50 μm | n/a | n/a | ∼10 min | Application of UHPLC for proteomics | [27] |

| Slurry Pressure | 72 | 1.0 μm, nonporous C18 | 10 mg/mL in 33% acetone/67% hexane | 46 cm × 30 μm | 180,000 | 2 | 2.8 min | Gradient UHPLC for first time | [28] |

| Slurry Pressure | 100 | 1.0 μm, nonporous C18 | 10–30 mg/mL in 33% acetone/67% hexane | 40–50 cm × 10–150 μm | 330,000 | 1.3 | 1.8 min | Over 100 kpsi operating pressure | [42] |

| Slurry Pressure | 65 | 1.5 μm, porous C18 | 5 mg/mL in acetone | 30–50 cm × 30 μm | 200,000 | 1.6 | 2.4 min | Use of porous particles above 20 kpsi | [43] |

| Slurry Pressure | 40 | 1.1 μm, superficially porous C18 | 25 mg/mL in methanol | 12 cm × 30 μm | 45,000 | 2.6 | n/a | Synthesis and evaluation of 1.1 μm superficially porous particles | [47] |

| Slurry Pressure | 40 | 1.5 μm, superficially porous C18 | 30 mg/mL in acetone | 32 cm × 30–75 μm | 170,000 | 1.24 | n/a | Efficient packing of superficially porous particles in capillaries | [48] |

| Slurry Pressure | 40 | 0.9–1.9 μm, porous C18 | 20–100 mg/mL in acetone | 20 cm × 30–75 μm | n/a | 1.5–1.9 | n/a | Slurry Concentration effects on separation efficiency | [49] |

| Slurry Pressure | 50 | 670 nm, nonporous C18 | 12.5 mg/mL in acetone | 9 cm × 50 μm | 45,000 | 3 | 1.2 min | Sub micron particles | [50] |

| Slurry Pressure | 26 | 1 μm, nonporous C4 (zirconia based) | n/a; 1:1 chloroform:cyclohexanol | 15 cm × 50 μm | 63,000 | 3 | 0.6 min | High Temperature (90 C) with UHPLC | [51] |

| Slurry Pressure | 40 | 1.3 μm, porous C18 | 20 mg/mL in acetone | 34 cm × 75 μm | 170,000 | 1.5 | 1.7 min | Efficient packing of porous, 1.3 μm particles | [62] |

| Slurry Pressure | 40 | 2 μm, porous C18 | 200 mg/mL in acetone | 100 cm × 75 μm | 470,000 | 1.05 | 10 min | Sonication while packing meter-long columns | [64] |

| Slurry Pressure | 11 (packed at 30) | 1.7 μm, porous C18 | 40–160 mg/mL in chloroform | 30 cm × 75 μm | n/a | n/a | ∼5 min | Comparison of packing pressure on proteomics experiments | [71] |

Slurry that produced the lowest plate height.

Highest number of plates achieved (not necessarily at the fastest time).

Fastest analysis time achieved.

3.1. Packing techniques

Capillary microcolumns have predominantly been employed for UHPLC over 20 kpsi due to their superior heat dissipation. Microcolumns have been packed using electroosmotic flow [35], centripetal forces [36], and pressure-driven slurries using conventional solvents and supercritical carbon dioxide [37]. Comparing the techniques in terms of column performance is difficult as packing techniques are commonly described as an art form. Regardless of this challenge, a single operator attempted all four of these techniques and ultimately produced similar performance for 20–45 cm long microcolumns with 3 μm particles [38]. Alternative column preparation methods include synthesis driven packing of monoliths and colloidal silica, which may remove many of the difficulties of conventional packing procedures. However, a larger reliance on well-defined reaction conditions is required for these methods, and stability at ultrahigh pressures is challenging [39–41]. As smaller and wider ranges of stationary phase particles have been synthesized, liquid slurry pressure packing has become the most widely used technique for UHPLC. In this section we will discuss column packing procedures primarily in relation to liquid slurry pressure packing techniques and factors that influence column performance for different particle and column dimensions.

3.2. Particle types

3.2.1. Reversed-phase: Nonporous, fully porous, and superficially porous

Early UHPLC studies heavily relied upon nonporous particles primarily due to their availability in small sizes. Nonporous reversed-phase (RP) particles ranging from 1.0 to 1.5 μm were packed at ~60 kpsi in 40–50 cm × 30 μm capillaries and operated up to 100 kpsi, generating up to 310,000 plates for a small molecule test mixture with on-column amperometric detection. Dead times were a few minutes, much faster than what would be possible at commercial pressures (Table 1) [23,28,42]. Fast separations (t0 ~30 s) were also demonstrated by the use of shorter columns (e.g. 10–15 cm) at 40 kpsi, while still achieving over 100,000 plates per meter (Table 1) [24].

While early work with nonporous particles laid the groundwork for UHPLC, the applications were limited due to the low loading capacity of these particles. With the introduction of sub-2 μm porous particles, differences in chromatographic performance were compared to nonporous particles [43,44]. Reduced plate heights as low as 1.6 were observed for 1.5 μm porous particles in 50 cm 30 μm i.d. capillaries suggesting efficient packing [43]. Higher C-terms were observed with porous particles at high linear velocities due to mass transfer contribution from the stagnant mobile phase [44]. Phase ratio predicts that for 1.0 μm particles with 10 nm pores, loading capacity should be about 22 times greater than that of 1.0 μm nonporous particles, making these particles amenable for analysis of complex mixtures. Synthesis and column packing of such small porous particles however has typically been more challenging compared to nonporous particles (discussed in section 3.3).

Superficially porous particles offer good balance between the column loading capacity of fully porous particles and small mass transfer and permeability of nonporous particles [45]. Synthesis of 1.1 μm superficially porous C18 particles was recently reported with a narrow particle size distribution of 2.2% [46], and subsequent kinetic performance exhibited a reduced plate height of 2.6, suggesting relatively good packing (Fig. 3A) [47]. The packing of slightly larger superficially porous particles (1.5 μm) reached reduced plate heights as low as 1.24 [48], corroborating the idea that smaller particles are more difficult to pack.

Fig. 3.

Reduced van Deemter plots illustrating the effect of slurry solvents with 3 mg/mL concentration on chromatographic performance for 1.1 μm superficially porous C18 particles packed in ~12 cm × 30 μm capillaries (A). The dashed line is performance expected from theory. Adapted with permission from Ref. [47]. Reduced van Deemter plots of 75 μm i.d. capillaries packed with 1.3 μm fully porous C18 particles shows the difficulty in packing longer columns (e.g. > 40 cm) with these small particles (B). A 100 cm column was packed and subsequently cut in to three sections with the last packed sections (center and inlet) exhibiting poor performance and dominating the overall column performance (100 cm - before cutting), illustrating large axial heterogeneities. Data from Reising et al., 2016 is a comparison of a single 34 cm column with the same 1.3 μm particles showing similar performance to the outlet of the 100 cm column, indicating minimal axial heterogeneities and good column packing for shorter columns under these conditions. Adapted with permission from Ref. [65].

3.2.2. Submicron

Submicron porous stationary phase particles are not yet commercially available for LC applications, but a few reports have demonstrated the potential use for UHPLC (Table 1) [49,50]. Reduced plate heights around 2 have been achieved for 630–900 nm porous particles operated around 40 kpsi, but column length was limited to 20 cm or less and large packing voids (~10 times particle diameter) were present, limiting total column efficiency. Excellent efficiencies and homogenous packing were reported for 330 nm silica colloidal crystals packed in short (~2.5 cm) 75 μm i.d. fused silica capillaries [41]. These silica colloidal crystals also exhibited slip flow, enhancing the flow rate compared to what would be expected in a typical packed bed (i.e. Hagen–Poiseuille flow) and providing smaller peak widths due to the narrower parabolic profile. However, pressures up to only 12.4 kpsi were used, limiting potential for higher throughput or efficiency. Altogether, submicron porous particles have seen limited use so far due to the difficulty in packing long columns and their high resistance to flow necessitating very high pressures (e.g. > 50 kpsi). Silica colloidal crystals could offset these restrictions due to slip flow.

3.2.3. Zirconia-based particles

Zirconia-based particles have been shown to provide distinct advantages over silica-based particles, notably their stability at very high temperatures. Higher temperature in HPLC is attractive for faster analysis due to lower viscosity and faster mass transfer. Very fast separations have been achieved with 1.0 μm polybutadiene-coated nonporous zirconia particles by use of pressures up to 26 kpsi and temperatures up to 90°C with no noticeable degradation [51,52]. The separation of small molecule herbicides on a 13 cm × 50 μm column was completed in 60 s, and efficiencies as high as 420,000 plates m−1 were achieved. Reduced plate heights of only 3.1 however were obtained primarily due to zirconia particles’ tendency to agglomerate.

3.2.4. Polymer-based and non-RP stationary phases below 20 kpsi

Fast and high resolution separations without the need for high pressures has been researched and will be discussed briefly here. Monolithic columns can provide high efficiency without high pressure due to their higher permeability [53]. For example, a series of monolithic microcolumns were coupled to a total length of ~12 m and operated at ~7 kpsi, producing 1,000,000 plates for a retained compound (k’ 2.4) with a dead time of 150 min. Polymer beads have also been used as stationary phases with advantageous including high surface area, highly monodisperse particle size synthesis, and the possibility for different separation mechanisms including RP, size exclusion (SEC), ion exchange (IEX), and hydrophilic interaction LC (HILIC) [54]. Column properties such as permeability and mass transfer resistance can be tailored by varying the size of the flow-through pores and mesopores. Separation of six proteins in 2 min was recently reported using poly (styrene-co-divinylbenzene) beads, which exhibited good protein recovery and wide-range pH stability [55]. Micro-machined columns such as micro pillar array columns (μPAC) have also been developed with similar advantages including low permeability and a highly ordered stationary phase, providing low eddy dispersion. Recently, a peak capacity of 1800 was achieved for small molecules in 2050 min using an 8 m long μPAC operated at commercial pressures [56]. Combining these techniques with pressures above 20 kpsi has not been done but could be beneficial for decreasing analysis time while maintaining performance, assuming the columns are stable and resistance to mass transfer is minimal, as the C-term region will dominate band broadening at higher linear velocities.

IEX and HILIC columns have also not been performed above 20 kpsi but are an attractive approach for orthogonal selectivity compared to RP. While small diameter particles with these stationary phase chemistries are available, they have largely been limited to commercial instrumentation. A recent example of a HILIC microcolumn utilized a meter-long column packed with 5 μm amide particles operated at ~0.7 kpsi, however a reduced plate height of only 4 was achieved, and a peak capacity of 130 was demonstrated for a 700 min gradient [57]. The effect of pressure on retention of macromolecules was recently studied under IEX conditions, with up to an 80% and 20% increase in retention being reported for isocratic and gradient separations, respectively [58]. Anion exchange using 2.5 μm particles up to 10 kpsi was recently studied and compared to 4 μm particles; the separation of anions in under 3 min was achieved while maintaining efficiency [59]. Further implementation of small HILIC and IEX stationary phases at higher pressures should provide higher efficiencies for these unique separation mechanisms and present opportunities for multi-dimensional UHPLC.

3.3. Packing conditions

Column packing for a given particle type often requires screening numerous conditions. An hmin < 2 is characteristic of a well-packed column and indicates low eddy dispersion and a homogenous bed. Notable packing conditions that have been shown to alter performance for RP capillaries are discussed below and summarized in Table 1. A limitation of the current reports on packing is that not all conditions are well-described, making it difficult to assess best approaches for packing. We believe it is essential that authors describe in detail their findings on packing conditions to promote use of these methods.

3.3.1. Slurry solvent and concentration

In analytical scale chromatography it is believed that a slurry solvent which promotes the dispersion of particles would pack an efficient column [60]. However, in capillaries it has been observed to be the opposite. For example with 1.1 μm superficially porous C18 particles, the most aggregating slurry solvent, methanol (assessed by optical microscopy), presented the best kinetic performance, likely by decreasing particle size segregation during packing (Fig. 3A) [47].

Slurry concentration also has a large effect on column performance. Numerous studies have shown that an intermediate slurry concentration gives the best performance, confirmed with morphological analysis via optical microscopy (during packing) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (after packing). Too high of a slurry concentration leads to voids in the bed, while too low of a slurry concentration leads to particle size segregation such that smaller particles travel to the wall, leading to radial heterogeneities that contribute to poor performance [49,61]. The “optimal” slurry concentration is largely dependent on particle size. For example, 140 mg/mL was found to be optimal for 1.9 μm particles, while 30 mg/mL was optimal for 1.3 μ m particles [61,62]. This is due to the observation that smaller particles have a higher tendency to form voids due to their high cohesive and frictional forces. Packing smaller particles (e.g. 1.3 μm and smaller) is especially problematic as larger packing voids have been identified in these columns [62].

The aspect ratio (dc/dp) can also influence column performance, with lower values typically giving better performance and sometimes overcoming the radial heterogeneities caused by low slurry concentrations [63]. It is thus important to recognize this variable when comparing columns of different particle sizes and/or column i.d.’s.

3.3.2. Sonication and packing rates

Sonication while packing has been investigated to mitigate the presence of packing voids [64]. Meter long capillaries packed with a 200 mg/mL slurry of 2.0 μm bridged-ethyl hybrid silica particles (when the optimal is 140 mg/mL without sonication [61]) achieved reduced plate heights as low as 1.05 and 470,000 plates.

Slurry packing can be performed at constant flow or constant pressure. With constant pressure, the pressure is immediately ramped to the highest point and the rate at which the bed packs decreases over column length and time, whereas in constant flow the pressure is gradually increased to maintain flow. A study employing constant pressure packing of 1.3 μm particles without the use of sonication packed a 1 m capillary before cutting it into three parts to evaluate potential axial heterogeneities [65]. The outlet, center, and inlet (in order of packing progress) were compared in terms of reduced plate height (Fig. 3B). The overall performance of the 1 m column was found to be most similar to the poorer performing center and inlet sections. The outlet section (first segment packed), however, was well-packed (hmin < 2) and performed similarly to a previously well-packed and shorter 34 cm capillary packed with the same particles [62] (Fig. 3B). Axial heterogeneities were found to be a major contributor to worse performance between these sections. Recent studies using flow reversal found similar axial heterogeneities in analytical columns [66]. Thus, to pack longer columns (e.g. ~ 1 m) with small (e.g. 1.3 μm or less) particles, further improvements in packing conditions must be made, potentially by use of higher slurry concentrations, sonication, or higher packing pressure to alleviate axial heterogeneities. Alternative packing techniques described above could also be implemented for these smaller particles and longer columns. For example, packing using centripetal forces has been shown to provide a more uniform impact velocity of particles through the column, potentially avoiding the axial heterogeneities observed with pressure driven slurry packing [36].

4. Applications

While column packing and highly efficient isocratic separations have been demonstrated, the applications of liquid chromatography above 20 kpsi has been sparse likely due to the difficulty of implementing reliable and robust gradient systems (see section 2.2). Nonetheless, there have been a few different applications which have illustrated the benefits of higher pressure to utilize long columns packed with small particles. These applications include the separation of chiral compounds [67], pharmaceutical and environmental compounds [51,68,69], lipidomics [70], and proteomics research [18,27,71,72]. In this section we will highlight some recent applications illustrating the advantages of ultrahigh pressure LC.

4.1. Bottom-up proteomics

The analysis of complex mixtures is perhaps the most attractive and popular avenue for applying ultrahigh pressure separations with the goal of increasing peak capacity or peak production rate. Proteomics is an ever-growing field that heavily relies on LC-tandem MS (MS/MS) for analysis. Comprehensive analysis of the proteome is challenging due to the complexity and large dynamic range. Bottom-up proteomics is a popular approach because peptides are more easily separated by RP-LC due to their smaller size and faster diffusion, and are also more easily identified and sequenced by MS/MS than their corresponding intact proteins [73]. Many researchers have described LC-MS systems capable of operation above 20 kpsi for bottom-up proteomics research [18]. These systems have generated peak capacities of 800–1500 for peptide samples in ~10–30 h analysis times. Use of ultrahigh pressures allowed implementation of long columns (e.g. up to 200 cm) and packed with sub-2 μm particles. Alternatively, high throughput bottom-up analyses have been demonstrated with the use of 10–20 cm columns packed with 0.8 μm C18 particles for analysis times of 1–50 min [74,75]. These results have outcompeted what is possible with commercial pressures and particle size/column length combinations, where peak capacities have rarely exceeded ~200–300. Multidimensional techniques such as online LC x LC however still often outcompete these one-dimensional separations, particularly in regard to peak capacity per unit time. Other factors such as MS acquisition rates must also be considered when moving to faster and higher efficiency separations; these limitations have been noted for both proteomics and other applications [69,76].

A recent study investigated the effect that packing capillary columns at ultrahigh pressure has on various bottom-up proteomic experiments [71]. Notably, columns packed above 20 kpsi showed enhanced permeability, separation peak capacity, and more peptide and protein identifications for a variety of sample complexities and injection loading amount compared to columns packed around 1 kpsi (Fig. 4). A modification to the seminal multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) was demonstrated with pressures of ~20 kpsi to operate a 60 cm long triphasic column [31]. This analysis resulted in a ~30% increase in protein identifications from a yeast lysate than what was possible with the traditional MudPIT assay.

Fig. 4.

Effect of column packing pressure on various proteomic experiments using 30 cm × 75 μm columns with fully porous 1.7 μm C18 particles. For the 11 kpsi case, columns were packed at ~1 kpsi and subsequently flushed at 11 kpsi. For the >20 kpsi case, columns were packed at either 20 or 30 kpsi. All columns were operated around 11 kpsi on a commercial capillary LC-MS system. Adapted with permission from Ref. [71]. Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society.

4.2. Top-down proteomics

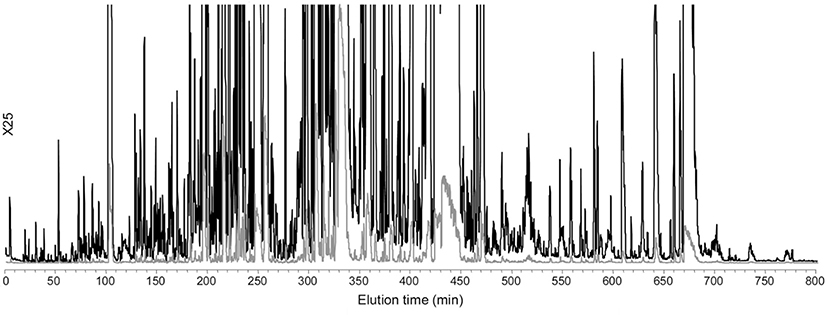

Although the bottom-up approach for proteomics has arguably dominated in the past, analysis of intact proteins is attractive because the sample is less complex and post-translational modifications can be easier to discern [77]. Separation of large, intact proteins is challenging however due to their slower diffusion and higher hydrophobicity compared to peptides. A recent study examined a number of chromatographic variables in an attempt to increase peak capacity for large (up to 43 kDa) proteins including particle diameter, column length, particle porosity, and alkyl chain length while operating around 20 kpsi [78]. They found that shorter alkyl chains (C2 – C4) on the stationary phase greatly out-performed the conventional C8 or C18 phases in terms of recovery and separation efficiency, likely due to increased partitioning into the shorter chains as opposed to adsorption/desorption with C8 and C8 chains. Additionally, column length (up to 200 cm) was found to be the most important factor for increasing separation peak capacity, regardless of particle size or surface structure. An example chromatogram of separation of a cell lysate on a 120 cm × 100 μm column packed with 3.6 μm core-shell C4 particles is shown in Fig. 5. A peak capacity of 450 was achieved in an 800-min gradient elution method using a home-built 20 kpsi system. An additional advantage of higher pressures for intact protein separations is the observation of decreased column carry-over, attributed to protein unfolding and de-aggregation [79]. Recent work has also shown that gradient volume plays an important role on overall peak capacity for intact proteins. The maximum peak capacity was achieved at a flow rate 20 times higher than the van Deemter optimal flow rate [80]. Capillary HILIC columns were also recently demonstrated to provide orthogonal separation of intact proteins and provided sensitive top-down proteomics [81]. Other researchers have demonstrated efficient separation of intact proteins using sub-micron colloidal silica particles with short columns (<5 cm) and commercial instrumentation [82,83]. Combining these particle domains with longer columns operated at higher pressures is an attractive area of research for further increasing separation performance of intact proteins and improving top down proteomic experiments.

Fig. 5.

Separation of intact, global proteoforms in S. oneidensis lysate on a 120 cm × 100 μm column packed with 3.6 μm C4 core-shell particles and operated at 14 kpsi. Effluent was connected to an Exactive mass spectrometer. A peak capacity of 450 was achieved in an 800-min gradient and ~900 proteoforms were identified. Adapted with permission from Ref. [78].

4.3. Metabolomics

While proteomics has matured over the past few decades, other -omics technologies have just begun to emerge, such as metabolomics, lipidomics, and transcriptomics. UHPLC-MS can be implemented in a variety of these areas, however widespread use has not been realized. The increasing availability of different particle chemistries and geometries will likely open the door for the use of LC in these areas. For example, core-shell C30 phases were recently shown to improve some lipid separations compared to C8 or C18 that is commonly employed [84]. Alternatively, porous graphitic carbon has been shown to greatly increase retention for many polar metabolites compared to conventional silica-based phases [85]. This phase however is only available down to 3 μm particle diameter, requiring the use of very long columns (e.g. 100–200 cm) for higher pressures to be beneficial.

4.4. High-speed separations

Most uses of pressures above 20 kpsi have been directed towards high-resolution separations of complex samples, utilizing long columns and gradient times on the hour timescale. The potential for fast separations at such high pressures using short columns packed with sub-2 μm particles has also been explored. Some notable reports are highlighted in Table 1. For example, a 6-component benzodiazepine mixture was separated in under 60 s using a 12.5 cm 29 μm column packed with 1.5 μm nonporous particles and operated at 40 kpsi [24]. While the linear velocity was much higher than optimal, efficiencies of 110,000 to 350,000 plates/m were obtained. Other work on high-speed LC separations above 20 kpsi have studied the feasibility of coupling with ion mobility separations and MS detection [24,69,86]. Recently, sub second separations have been demonstrated and have shown promise for high-throughput LC [87]. This work has primarily been done using commercial instrumentation, as the benefits of higher pressure diminishes when t0 becomes very small (see Fig. 1). Additionally, other difficulties such as autosampler speed, detector response time, column re-equilibration, and low extra-column dispersion remain a bottleneck for taking full advantage of these high-speed separations [88]. We anticipate further growth of separations in the seconds time scale with applications in sensing and high-throughput analysis.

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

UHPLC can greatly improve separation speed and efficiency through use of small particles and/or long columns, allowing higher throughput and more in-depth analysis of various biological or other complex systems. Fabrication of new valves and nuts that reliably work at 50–100 kpsi is of interest to further increase separation performance by decreasing the optimal particle size while maintaining comparable column lengths. Minimization of extra column effects due to injection and extra column tubing will be necessary as peak volumes become smaller, especially for very fast separations. Alternative stationary phase materials will find much attention in the future. Almost all past work has involved RP chemistries as packing material. HILIC and IEX chromatography at ultrahigh pressures is attractive for improving separation of polar and charged analytes. Other modes such as size exclusion and hydrophobic interaction liquid chromatography may also benefit from higher operating pressure, offering faster or higher efficiency separations [89,90]. Packing procedures will likely need to be further optimized and studied when moving to alternative stationary phase chemistries or smaller particles, particularly for long columns. Numerous applications have illustrated the advantages of operating LC above 20 kpsi. Large improvements in peak capacity have been achieved by utilizing long columns packed with small particles. These separation improvements have led to large gains in information content in proteomics and other -omics technologies. Continued improvements in MS instrumentation, particularly acquisition rates, are also necessary for realizing the gain in separation quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the National Institute of Health for funding (Grant 1R01DK101473).

References

- [1].Snyder LR, Kirkland JJ, Dolan JW, Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography, third ed., Wiley, Hoboken, N.J, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fekete S, Schappler J, Veuthey J-L, Guillarme D, Current and future trends in UHPLC, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. (Reference Ed.) 63 (2014) 2–13. 10.1016/j.trac.2014.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Desmet G, Clicq D, Gzil P, Geometry-independent plate height representation methods for the direct comparison of the kinetic performance of LC supports with a different size or morphology, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 4058–4070. 10.1021/ac050160z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Poppe H, Some reflections on speed and efficiency of modern chromatographic methods, J. Chromatogr., A 778 (1997) 3–21. 10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00376-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McCalley DV, The impact of pressure and frictional heating on retention, selectivity and efficiency in ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. (Reference Ed.) 63 (2014) 31–43. 10.1016/j.trac.2014.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jorgenson JW, Capillary liquid chromatography at ultrahigh pressures, Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 3 (2010) 129–150. 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Anspach JA, Maloney TD, Brice RW, Colón LA, Injection valve for ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 7489–7494. 10.1021/ac051213f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Colón LA, Cintrón JM, Anspach JA, Fermier AM, Swinney KA, Very high pressure HPLC with 1 mm id columns, Analyst 129 (2004) 503–504. 10.1039/B405242K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Anspach JA, Maloney TD, Colón LA, Ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography using a 1-mm id column packed with 1.5-μm porous particles, J. Separ. Sci. 30 (2007) 1207–1213. 10.1002/jssc.200600535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Broeckhoven K, Desmet G, Considerations for the use of ultra-high pressures in liquid chromatography for 2.1 mm inner diameter columns, J. Chromatogr., A 1523 (2017) 183–192. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lambert N, Felinger A, The effect of the frictional heat on retention and efficiency in thermostated or insulated chromatographic columns packed with sub-2-μm particles, J. Chromatogr., A 1565 (2018) 89–95. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Grinias JP, Keil DS, Jorgenson JW, Observation of enhanced heat dissipation in columns packed with superficially porous particles, J. Chromatogr., A 1371 (2014) 261–264. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Broeckhoven K, Desmet G, Advances and challenges in extremely high-pressure liquid chromatography in current and future analytical scale column formats, Anal. Chem. 92 (1) (2019) 554–560. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sěsták J, Moravcová D, Kahle V, Instrument platforms for nano liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1421 (2015) 2–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Aggarwal P, Liu K, Sharma S, Lawson JS, Dennis Tolley H, Lee ML, Flow rate dependent extra-column variance from injection in capillary liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1380 (2015) 38–44. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gritti F, Tanaka N, Slow injector-to-column sample transport to maximize resolution in liquid chromatography: theory versus practice, J. Chromatogr., A 1600 (2019) 219–237. 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rogers BA, Wu Z, Wei B, Zhang X, Cao X, Alabi O, Wirth MJ, Submicrometer particles and slip flow in liquid chromatography, Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 2520–2526. 10.1021/ac504683d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blue LE, Franklin EG, Godinho JM, Grinias JP, Grinias KM, Lunn DB, Moore SM, Recent advances in capillary ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1523 (2017) 17–39. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leonhardt J, Hetzel T, Teutenberg T, Schmidt TC, Large volume injection of aqueous samples in nano liquid chromatography using serially coupled columns, Chromatographia 78 (2015) 31–38. 10.1007/s10337-014-2789-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Groskreutz SR, Weber SG, Quantitative evaluation of models for solvent-based, on-column focusing in liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1409 (2015) 116–124. 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Vanderlinden K, Broeckhoven K, Vanderheyden Y, Desmet G, Effect of pre- and post-column band broadening on the performance of high-speed chromatography columns under isocratic and gradient conditions, J. Chromatogr., A 1442 (2016) 73–82. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Buckenmaier S, Miller CA, van de Goor T, Dittmann MM, Instrument contributions to resolution and sensitivity in ultra high performance liquid chromatography using small bore columns: comparison of diode array and triple quadrupole mass spectrometry detection, J. Chromatogr., A 1377 (2015) 64–74. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].MacNair JE, Lewis KC, Jorgenson JW, Ultrahigh-pressure reversed-phase liquid chromatography in packed capillary columns, Anal. Chem. 69 (1997) 983–989. 10.1021/ac961094r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lippert JA, Xin B, Wu N, Lee ML, Fast ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography: on-column UV and time-of-flight mass spectrometric detection, J. Microcolumn Sep. 11 (1999) 631–643. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pepermans V, De Vos J, Eeltink S, Desmet G, Peak sharpening limits of solvent-assisted post-column refocusing to enhance detection limits in liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1586 (2019) 52–61. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gritti F, Guiochon G, On the extra-column band-broadening contributions of modern, very high pressure liquid chromatographs using 2.1mm I.D. columns packed with sub-2μm particles, J. Chromatogr., A 1217 (2010) 7677–7689. 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shen Y, Zhang R, Moore RJ, Kim J, Metz TO, Hixson KK, Zhao R, Livesay EA, Udset HRh, Smith RD, Automated 20 kpsi RPLC-MS and MS/MS with chromatographic peak capacities of 1000 1500 and capabilities in proteomics and metabolomics, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 3090––3100.. 10.1021/ac0483062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].MacNair JE, Patel KD, Jorgenson JW, Ultrahigh-pressure reversed-phase capillary liquid chromatography: isocratic and gradient elution using columns packed with 1.0-μm particles, Anal. Chem. 71 (1999) 700–708. 10.1021/ac9807013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xiang Y, Liu Y, Stearns SD, Plistil A, Brisbin MP, Lee ML, Pseudolinear gradient ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography using an injection valve assembly, Anal. Chem. 78 (2006) 858–864. 10.1021/ac058024h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Grinias KM, Godinho JM, Franklin EG, Stobaugh JT, Jorgenson JW, Development of a 45kpsi ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography instrument for gradient separations of peptides using long microcapillary columns and sub-2μm particles, J. Chromatogr., A 1469 (2016) 60–67. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Motoyama A, Venable JD, Ruse CI, Yates JR, Automated ultra-high-pressure multidimensional protein identification technology (UHP-MudPIT) for improved peptide identification of proteomic samples, Anal. Chem. 78 (2006) 5109–5118. 10.1021/ac060354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Pauw R, Swier T, Degreef B, Desmet G, Broeckhoven K, On the feasibility to conduct gradient liquid chromatography separations in narrow-bore columns at pressures up to 2000 bar, J. Chromatogr., A 1473 (2016) 48–55. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gritti F, Stankovich JJ, Guiochon G, Potential advantage of constant pressure versus constant flow gradient chromatography for the analysis of small molecules, J. Chromatogr., A 1263 (2012) 51–60. 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bevan CD, Mutton IM, Freeze-thaw flow management: a novel concept for high-performance liquid chromatography, capillary electrophoresis, electrochromatography and associated techniques, J. Chromatogr., A 697 (1995) 541–548. 10.1016/0021-9673(94)00954-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yan C, Electrokinetic packing of capillary columns, US Pat 5453163 (1995).

- [36].Fermier AM, Coloón Luis A., Capillary electrochromatography in columns packed by centripetal forces, J. Microcolumn Sep. 10 (1998) 439–447. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Malik A, Li W, Lee ML, Preparation of long packed capillary columns using carbon dioxide slurries, J. Microcolumn Sep. 5 (1993) 361–369. 10.1002/mcs.1220050409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Maloney TD, Colón LA, Comparison of column packing techniques for capillary electrochromatography, J. Separ. Sci. 25 (2002) 1215–1225. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gu C, Jia Z, Zhu Z, He C, Wang W, Morgan A, Lu JJ, Liu S, Miniaturized electroosmotic pump capable of generating pressures of more than 1200 bar, Anal. Chem. 84 (2012) 9609–9614. 10.1021/ac3025703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hara T, Eeltink S, Desmet G, Exploring the pressure resistance limits of monolithic silica capillary columns, J. Chromatogr., A 1446 (2016) 164–169. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Malkin DS, Wei B, Fogiel AJ, Staats SL, Wirth MJ, Submicrometer plate heights for capillaries packed with silica colloidal crystals, Anal. Chem. 82 (2010) 2175–2177. 10.1021/ac100062t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Patel KD, Jerkovich AD, Link Jason C., Jorgenson JW, In-depth characterization of slurry packed capillary columns with 1.0-um nonporous particles using reversed-phase isocratic ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography, Anal. Chem. 76 (2004) 5777–5786. 10.1021/AC049756X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mellors JS, Jorgenson JW, Use of 1.5-um porous ethyl-bridged hybrid particles as a stationary-phase support for reversed-phase ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography, Anal. Chem. 76 (2004) 5441–5450. 10.1021/ac049643d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wu N, Liu Y, Lee ML, Sub-2μm porous and nonporous particles for fast separation in reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1131 (2006) 142–150. 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gritti F, Omamogho J, Guiochon G, Kinetic investigation of narrow-bore columns packed with prototype sub-2 μm superficially porous particles with various shell thickness, J. Chromatogr., A 1218 (2011) 7078–7093. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blue LE, Jorgenson JW, 1.1 μm superficially porous particles for liquid chromatography. Part I: synthesis and particle structure characterization, J. Chromatogr., A 1218 (2011) 7989–7995. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Blue LE, Jorgenson JW, 1.1um Superficially porous particles for liquid chromatography. Part II: column packing and chromatographic performance, J. Chromatogr., A 1380 (2015) 71–80. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Treadway JW, Wyndham KD, Jorgenson JW, Highly efficient capillary columns packed with superficially porous particles via sequential column packing, J. Chromatogr., A 1422 (2015) 345–349. 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bruns S, Franklin EG, Grinias JP, Godinho JM, Jorgenson JW, Tallarek U, Slurry concentration effects on the bed morphology and separation efficiency of capillaries packed with sub-2μm particles, J. Chromatogr., A 1318 (2013) 189–197. 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cintrón JM, Colón LA, Organo-silica nano-particles used n ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography, Analyst 127 (2002) 701–704. 10.1039/b203236h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Xiang Y, Yan B, Yue B, McNeff CV, Carr PW, Lee ML, Elevated-temperature ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography using very small polybutadiene-coated nonporous zirconia particles, J. Chromatogr., A 983 (2003) 83–89. 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)01662-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Xiang Y, Yan B, McNeff CV, Carr PW, Lee ML, Synthesis of micron diameter polybutadiene-encapsulated non-porous zirconia particles for ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1002 (2003) 71–78. 10.1016/S0021-9673(03)00733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Svec F, Lv Y, Advances and recent trends in the field of monolithic columns for chromatography, Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 250–273. 10.1021/ac504059c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yu B, Xu T, Cong H, Peng Q, Usman M, Preparation of porous poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) microspheres and their modification with diazoresin for mix-mode HPLC separations, Materials 10 (2017) 440 10.3390/ma10040440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li Q, Ma L, Xu L, Fast reversed-phase liquid chromatographic separation of proteins by flow-through poly(styrene- co -divinylbenzene) microspheres, J. Separ. Sci. 42 (2019) 2788–2795. 10.1002/jssc.201900292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Baca M, Desmet G, Ottevaere H, De Malsche W, Achieving a peak capacity of 1800 using an 8 m long pillar array column, Anal. Chem. 91 (2019) 10932–10936. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Liu Y, Wang X, Chen Z, Liang DH, Sun K, Huang S, Zhu J, Shi X, Zeng J, Wang Q, Zhang B, Towards a high peak capacity of 130 using nanoflow hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, Anal. Chim. Acta 1062 (2019) 147–155. 10.1016/j.aca.2019.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kristl A, Lokošek P, Pompe M, Podgornik A, Effect of pressure on the retention of macromolecules in ion exchange chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 1597 (2019) 89–99. 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wouters S, Dores-Sousa JL, Liu Y, Pohl CA, Eeltink S, Ultra-high-pressure ion chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection at 70 MPa using columns packed with 2.5 μm anion-exchange particles, Anal. Chem. 91 (21) (2019) 13824–13830. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wahab MF, Patel DC, Wimalasinghe RM, Armstrong DW, Fundamental and practical insights on the packing of modern high-efficiency analytical and capillary columns, Anal. Chem. 89 (2017) 8177–8191. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Reising AE, Godinho JM, Jorgenson JW, Tallarek U, Bed morphological features associated with an optimal slurry concentration for reproducible preparation of efficient capillary ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography columns, J. Chromatogr., A 1504 (2017) 71–82. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Reising AE, Godinho JM, Hormann K, Jorgenson JW, Tallarek U, Larger voids in mechanically stable, loose packings of 1.3 um frictional, cohesive particles: their reconstruction, statistical analysis, and impact on separation efficiency, J. Chromatogr., A 1436 (2016) 118–132. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bruns S, Grinias JP, Blue LE, Jorgenson JW, Tallarek U, Morphology and separation efficiency of low-aspect-ratio capillary ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography columns, Anal. Chem. 84 (2012) 4496–4503. 10.1021/ac300326k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Godinho JM, Reising AE, Tallarek U, Jorgenson JW, Implementation of high slurry concentration and sonication to pack high-efficiency, meter-long capillary ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography columns, J. Chromatogr., A 1462 (2016) 165–169. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Reising AE, Godinho JM, Bernzen J, Jorgenson JW, Tallarek U, Axial heterogeneities in capillary ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography columns: chromatographic and bed morphological characterization, J. Chromatogr., A 1569 (2018) 44–52. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zelenyánszki D, Lambert N, Gritti F, Felinger A , The effect of column packing procedure on column end efficiency and on bed heterogeneity – experiments with flow-reversal, J. Chromatogr., A 1603 (2019) 412–416. 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Xiang Y, Wu N, Lippert JA, Lee ML, Separation of chiral pharmaceuticals using ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography, Chromatographia 55 (2002) 399–403. 10.1007/BF02492267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu N, Lippert JA, Lee ML, Practical aspects of ultrahigh pressure capillary liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr., A 911 (2001) 1–12. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)01188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wu N, Collins DC, Lippert JA, Xiang Y, Lee ML, Ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry for fast separations, J. Microcolumn Sep. 12 (2000) 462–469. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sorensen MJ, Miller KE, Jorgenson JW, Kennedy RT, Ultrahigh-performance capillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry at 35 kpsi for separation of lipids, J. Chromatogr. A (2019) 460575 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shishkova E, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Coon JJ, Ultra-high pressure (>30,000 psi) packing of capillary columns enhancing depth of shotgun proteomic analyses, Anal. Chem. 90 (2018) 11503–11508. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Mozziconacci O, Stobaugh JT, Bommana R, Woods J, Franklin E, Jorgenson JW, Forrest ML, Schoöcneich C, Stobaugh JF, Profiling the photochemical-induced degradation of rat growth hormone with extreme ultra-pressure chromatography–mass spectrometry utilizing meter-long microcapillary columns packed with sub-2-μm particles, Chromatographia 80 (2017) 1299–1318. 10.1007/s10337-017-3344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zhang Y, Fonslow BR, Shan B, Baek M-C, Yates JR, Protein analysis by shotgun/bottom-up proteomics, Chem. Rev. 113 (2013) 2343–2394. 10.1021/cr3003533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Shen Y, Smith RD, Unger KK, Kumar D, Lubda D, Ultrahigh-throughput proteomics using fast RPLC separations with ESI-MS/MS, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 6692–6701. 10.1021/ac050876u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Shen Y, Strittmatter EF, Zhang R, Metz TO, Moore RJ, Li F, Udseth HR, Smith RD, Unger KK, Kumar D, Lubda D, Making broad proteome protein measurements in 1–5 min using high-speed RPLC separations and high-accuracy mass measurements, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 7763–7773. 10.1021/ac051257o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Shishkova E, Hebert AS, Coon JJ, Now, more than ever, proteomics needs better chromatography, Cell Syst 3 (2016) 321–324. 10.1016/j.cels.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Catherman AD, Skinner OS, Kelleher NL, Top down proteomics: facts and perspectives, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 445 (2014) 683–693. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Shen Y, Tolíc N, Piehowski PD, Shukla AK, Kim S, Zhao R, Qu Y, Robinson E, Smith RD, Paša-Tolíc L, High-resolution ultrahigh-pressure long column reversed-phase liquid chromatography for top-down proteomics, J. Chromatogr., A 1498 (2017) 99–110. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Eschelbach JW, Jorgenson JW, Improved protein recovery in reversed-phase liquid chromatography by the use of ultrahigh pressures, Anal. Chem. 78 (2006) 1697–1706. 10.1021/ac0518304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Fernández-Pumarega A, Dores-Sousa JL, Eeltink S, A comprehensive investigation of the peak capacity for the reversed-phase gradient liquid-chromatographic analysis of intact proteins using a polymer-monolithic capillary column, J. Chromatogr., A 1609 (2019) 460462 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Gargano AFG, Roca LS, Fellers RT, Bocxe M, Domínguez-Vega E, Somsen GW, Capillary HILIC-MS: a new tool for sensitive top-down proteomics, Anal. Chem. 90 (2018) 6601–6609. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Rogers BJ, Birdsall RE, Wu Z, Wirth MJ, RPLC of intact proteins using sub-0.5 μm particles and commercial instrumentation, Anal. Chem. 85 (2013) 6820–6825. 10.1021/ac400982w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Wu Z, Wei B, Zhang X, Wirth MJ, Efficient separations of intact proteins using slip-flow with nano-liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 1592–1598. 10.1021/ac403233d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Narváez-Rivas M, Zhang Q , Comprehensive untargeted lipidomic analysis using core–shell C30 particle column and high field orbitrap mass spectrometer, J. Chromatogr., A 1440 (2016) 123–134. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lunn DB, Yun YJ, Jorgenson JW, Retention and effective diffusion of model metabolites on porous graphitic carbon, J. Chromatogr., A 1530 (2017) 112–119. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Collins DC, Xiang Y, Lee ML, Comprehensive ultra-high pressure capillary liquid chromatography/ion mobility spectrometry, Chromatographia 55 (2002) 123–128. 10.1007/BF02492131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Patel DC, Breitbach ZS, Wahab MF, Barhate CL, Armstrong DW, Gone in seconds: praxis, performance, and peculiarities of ultrafast chiral liquid chromatography with superficially porous particles, Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 9137–9148. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kaplitz AS, Kresge GA, Selover B, Horvat L, Franklin EG, Godinho JM, Grinias KM, Foster SW, Davis JJ, Grinias JP, High-throughput and ultrafast liquid chromatography, Anal. Chem. 92 (1) (2019) 67–84. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Wouters B, Bruggink C, Desmet G, Agroskin Y, Pohl CA, Eeltink S, Capillary ion chromatography at high pressure and temperature, Anal. Chem. 84 (2012) 7212–7217. 10.1021/ac301598j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Bouvier ESP, Koza SM, Advances in size-exclusion separations of proteins and polymers by UHPLC, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. (Reference Ed.) 63 (2014) 85–94. 10.1016/j.trac.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]