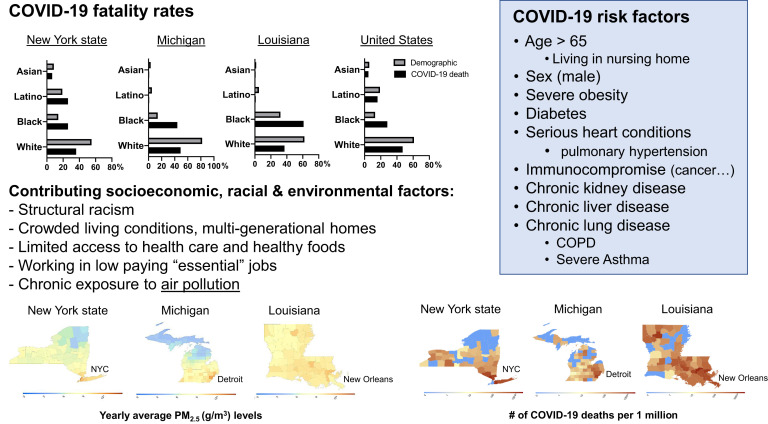

Since late 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected millions of people worldwide and resulted in more than 200,000 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) deaths. Emerging data suggest that elderly people as well as individuals with underlying health conditions are at a higher risk of hospitalization and death.1, 2, 3 Interestingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s list of risk factors for severe COVID-19 (Fig 1 ) largely overlap with the list of diseases that are known to be worsened by chronic exposure to air pollution, including diabetes, heart diseases, and chronic airway diseases, such as asthma, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3 In this editorial, we highlight potential links between exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 severity, and we also hypothesize that disparate exposure to air pollution is one of the factors that contribute to the disproportionate impact COVID-19 is having on inner-city racial minorities.

Fig 1.

Impact of air pollution and racial disparities on COVID-19 mortality. Racial breakdown of COVID-19 data as of April 24, 2020, was obtained from APM Research Lab (https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race). Additional racial disparity sources: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/; https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/nyregion/coronavirus-race-deaths.html; http://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-coronavirus-chicago-coronavirus-deaths-demographics-lightfoot-20200406-77nlylhiavgjzb2wa4ckivh7mu-story.html. Average PM2.5 concentrations (g/m3) for the years 2000 to 2016 were obtained from Atmospheric Composition Analysis (http://fizz.phys.dal.ca/∼atmos/martin). Figures were created by merging county-level data in a given state. The county-level COVID-19 death counts, adjusted for a population of 1 million, as of April 24, 2020, were obtained from Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Case Tracker: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. COVID-19 risk factors are based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s insights (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html). COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Air pollution is a complex mixture of particulate matter smaller than 2.5 or 10 μm (PM2.5, PM10), nitric dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3), and volatile organic compounds derived from vehicular traffic, industrial emissions, and indoor pollutants. Given overwhelming evidence linking chronic exposure to air pollution with increased morbidity and mortality across a range of cardiopulmonary diseases,4 there is growing concern that air pollution may also contribute to COVID-19 severity, by directly affecting the lungs’ ability to clear pathogens and indirectly by exacerbating underlying cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases.

Such a link was reported during the 2003 SARS outbreak in China, where a positive association was observed between both acute and chronic pollution measures from the air pollution index (CO, NO2, SO2, O3, and PM10) and SARS case-fatality rates.5 Now, preliminary data are suggesting similar associations for COVID-19. In cities of China’s Hubei province, the epicenter of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, there is evidence of a significant positive correlation between air pollution levels and higher morbidity and mortality rates from COVID-19. Yao et al6 assessed the correlation between the spread of COVID-19 and NO2 pollution. They conducted a cross-sectional analysis to examine the spatial associations of NO2 and COVID-19 transmission rates (R0), and longitudinal analyses to examine day-by-day spread-pollution associations in the cities. Their results showed positive correlations between NO2 pollution levels and R0 for COVID-19 after adjusting for temperature and humidity. In other words, the higher the NO2 pollution, the greater the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (and onset of COVID-19).6 The same group conducted cross-sectional analyses to examine the spatial associations of daily PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations with mortality rates from COVID-19 in China. Their results confirm that increased concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 are linked to higher death rates from COVID-19 (P = .011 and P = .015, respectively) on a spatial scale. In addition, a higher COVID-19 case-fatality rate was observed with increasing concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 on a temporal scale after adjusting for temperature and humidity.7

As SARS-CoV-2 has spread across the globe, additional evidence linking both acute and chronic air pollution to COVID-19 outcomes has been reported. Researchers at Dali University carried out an empirical investigation of air pollution and COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in 3 of the most affected countries (China, Italy, and the United States).2 They used annual indices of air quality from the Sentinel-5 satellite and ground information from each country while controlling for the area of interest’s population size. They found higher rates of COVID-19 infection in areas with high PM2.5, NO2, and CO.2 Similarly, an Italian study found that long-term air-quality data (NO2, O3, PM2.5, and PM10) significantly correlated with cases of COVID-19 in up to 71 Italian provinces.8 In the United States, a newly released study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health used data collected from approximately 3000 US counties to investigate whether long-term average exposure to PM2.5 increased the risk of death from COVID-19. They found that with an increase of only 1 μg/m3 in chronic PM2.5 exposure, the COVID-19 mortality rate increased by 15%.9

COVID-19 death rates appear higher in densely populated urban areas, where SARS-CoV2 can easily spread. Indeed, when we focused on some of the hardest hit states (New York and Michigan), their biggest cities (New York City and Detroit, respectively) had a much larger portion of COVID-19 deaths even after adjusting for population (Fig 1). These densely populated urban areas also had some of the highest air pollution, as assessed by yearly PM2.5 levels (Fig 1). Although population density promotes viral spread and air pollution, it fails to explain why the Bronx has twice the number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities than nearby Manhattan, pointing to socioeconomic and racial disparities (30% of Bronx county residents live below the poverty line, most of them black and Latino). Early data from Michigan’s outbreak suggest that 33% of COVID-19 cases and 44% of deaths were experienced by blacks even though they represent just 14% of the state population (Fig 1). In Detroit, up to 75% of all COVID-19 fatalities were blacks, whereas in Chicago, more than 50% of COVID-19 cases and nearly 70% of COVID-19 deaths involve black individuals, although they make up only 30% of the population. In Louisiana, 61% of deaths have occurred among blacks although they represent just 32% of the state’s population (Fig 1). With the caveat that many US areas have not released COVID-19 morbidity and mortality data by race/ethnicity and others still have incomplete racial breakdown, blacks represent 28% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States, more than twice their population demographics (Fig 1).

There are many compelling reasons why racial minorities experience disparate health outcomes across a range of conditions, including COVID-19. Indeed, the realities of structural racism have determined, over decades, the socioeconomic and environmental context in which many minorities live. In the United States, blacks are far more likely to experience adverse housing conditions, crowded living environments, diminished access to health-promoting resources (eg, health care and healthy food options), use of public transportation, be employed in sectors requiring close interactions with others (eg, food and service industries, sanitation, and public transportation), and also increased exposure to air pollution. According to the American Lung Association, an estimated 141 million Americans live in counties with unhealthy levels of air pollution. Lower income communities of color are more likely to have historical exposures to higher levels of air pollution.10 This chronic exposure is thought to worsen underlying diseases, including many that represent risk factors for severe COVID-19 (Fig 1).

Ongoing and future studies need therefore to assess the impact of air pollution on COVID-19 mortality in light of population density, and racial and socioeconomic segregation, and take into account the modulating effect of socioeconomic status on air pollution exposure. In addition, changes in air pollution as a result of stay-at-home policies and changing seasons warrants further investigation and should include low-income communities with high and low exposure to air pollution. Importantly, fine and ultrafine pollution particles can cross into the bloodstream and accumulate in tissues over a lifetime, explaining the reported associations observed in China, Italy, and the United States between chronic exposure to air pollution and increased mortality from not only lung diseases but also cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, which disproportionally afflict racial minorities. Furthermore, blacks and other low-income communities living in highly polluted areas will likely still be exposed to relatively higher levels of PM2.5 when compared with less-polluted areas even as PM2.5 decreases across the globe following stay-at-home orders. As ongoing COVID-19 studies are released almost daily, black patients are experiencing hospitalizations and death at disproportionately high rates, and strategies to mitigate these unacceptable outcomes are urgently needed. These studies also need to take into account different characteristics of, experiences with, and timing of policies meant to keep COVID-19 at bay.

In summary, although the relationship between air pollution and cardiopulmonary diseases is well-established, further research is required to delineate the specific mechanistic link between air pollution and severe outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as how air pollution may contribute to disparities in COVID-19–related outcomes.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. R01HL132344 and 2U19AI70235-12).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pansini R, Fornacca D. Initial evidence of higher morbidity and mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 in regions with lower air quality [published online ahead of print April 16, 2020]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.04.20053595.

- 3.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print March 13, 2020]. JAMA Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cohen A.J., Brauer M., Burnett R., Anderson H.R., Frostad J., Estep K. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui Y., Zhang Z.F., Froines J., Zhao J., Wang H., Yu S.Z. Air pollution and case fatality of SARS in the People's Republic of China: an ecologic study. Environ Health. 2003;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao Y, Pan J, Liu Z, Meng X, Wang W, Kan H, et al. Ambient nitrogen dioxide pollution and spread ability of COVID-19 in Chinese cities [published online ahead of print April 10, 2020]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.31.20048595.

- 7.Yao Y, Pan J, Liu Z, Meng X, Wang W, Kan H, et al. Temporal association between particulate matter pollution and case fatality rate of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print April 10, 2020]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20049924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ Pollut. 2020:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X, Nethery R, Sabath B, Braun D, Dominici F. Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States [published online ahead of print April 27, 2020]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.05.20054502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Tessum C.W., Apte J.S., Goodkind A.L., Muller N.Z., Mullins K.A., Paolella D.A. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:6001–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818859116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]