Abstract

The emergency department (ED) provides immediate access to medical care for patients and families in times of need. Increasingly, older patients with serious illness seek care in the ED, hoping for relief from symptoms and suffering associated with advanced disease. Until recently, emergency medicine (EM) clinicians have been ill‐equipped to meet the needs of patients with serious illness, and palliative services have been largely unavailable in the ED. However, in the past decade, there has been growing recognition from within both the EM and palliative medicine communities on the importance of palliative care provision in the ED. The past 10 years have seen a surge in EM–palliative care training and education, quality improvement projects, and research. As a result, the practice paradigm within EM for the seriously ill has begun to shift to incorporate more palliative care practices. Despite this progress, substantial work has yet to be done in terms of identifying ED patients in need of palliative care, training EM clinicians to provide high‐quality primary palliative care, creating pathways for ED referral to palliative care and hospice, and researching the outcomes and impact of palliative care provision on patients with serious illness in the ED.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, geriatrics, palliative care

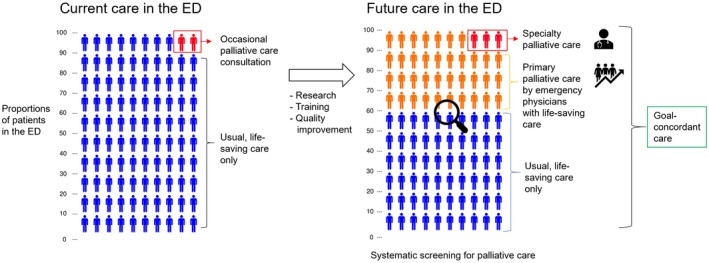

To meet the growing needs of older adults with serious illness in the emergency department, changes are steadily occurring in the practice of emergency medicine in the USA to incorporate palliative care.

![]()

Introduction – changing demographics and unmet needs

The aging of the population along with advances in disease‐directed therapy has resulted in a growing number of older adults living with serious illness, such as advanced cancer, chronic lung disease, or congestive heart failure.1, 2, 3 Increasingly, these patients seek care in the emergency department (ED). Adults age 75 years and older account for over 10 million ED visits per year, and those over 65 have the highest ED utilization rates as compared to all other age groups.4, 5, 6 In fact, half of older adults will visit the ED in their last month of life, many of whom will be admitted and subsequently die in the hospital.7

Older adults with serious illness presenting to the ED may require attention for immediately life‐threatening conditions, or may be suffering from severe physical symptoms, psychological distress, caregiver burdens, and unrecognized psychological or spiritual crises. Care for patients with serious illness should focus on goal‐concordant treatments – treatments that promote the patient’s preferences and values.8 However, traditionally the dominant paradigm in emergency medicine (EM) has been therapies to maintain life at all costs – often without attention to a patients’ prognosis, treatment values, and preferences for care.

The majority of older adults with serious illness report that they prefer medical therapies that will maximize their time at home, and minimize the experience of pain and other burdensome symptoms.9 Most prefer to avoid invasive therapies that have a low likelihood of promoting an acceptable quality of life (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation).10 Yet, for the majority of older adults with serious illness, the care received in the months and years prior to death is frequently discordant with these preferences and values. Care in the ED is often focused on intensive life‐sustaining interventions11, 12, 13, 14 and fails to address burdensome symptoms or invasive therapies possibly unaligned with patient’s wishes.15, 16, 17, 18 As a result, many older adults with serious illness spend their final days in and out of the ED, often dying in the hospital or intensive care unit.14 The financial costs of providing goal‐discordant care are staggering; more than 25% of Medicare dollars are spent in the last year of life, 50% in the last month.15 The ED has been a common launching point for medically aggressive, high cost, low‐quality, end‐of‐life (EOL) care.10

The past – shifting paradigms; integration of palliative care and emergency medicine

Early efforts to address the palliative care needs of seriously ill patients in the ED were born out of a recognition that emergency physicians play an important role in providing care at the end of life. In 2003, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Board of Directors released a statement directing emergency physicians to help patients and families “achieve greater control over the dying process” and “improve EOL care.”19 The Directors conveyed that emergency physicians had a duty to develop communication skills and clinical approaches that attend to the needs of patients with serious illness.

In 2003, little was available in the way of education, training, practice guidelines, or research to support emergency physicians hoping to incorporate palliative medicine in their practice. However, with acknowledgement from ACEP of the growing need for palliative care in the ED, the ground began to shift, and numerous local and national projects aimed at improving palliative care in the ED emerged. In the decade that followed, educational programs, such as Education in Palliative and End‐of‐Life Care (EPEC‐EM),20 and quality improvement programs, including the Center to Advance Palliative Care’s (CAPC) Improving Palliative Care in Emergency Medicine (IPAL‐EM)21 program were established. Research efforts during this period included observational and randomized trials, and pointed to several benefits to palliative care in the ED including, improved hospital outcomes,22 reduced hospital length of stay,22 improved patient and family satisfaction, and cost savings.23, 24 Although promising, these early efforts involved only a small fraction of EM practice nationally, and widely adopted change was yet to occur.

Two developments, in 2006 and 2012, respectively, catalyzed the speed of change in EM practice. First, in 2006, Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM) became an officially recognized subspecialty of the American Board of Medical Specialties. One of the 10 specialties allowed to pursue HPM fellowship certification was EM. Shortly after the recognition of HPM as a subspecialty, The American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) created a pathway for emergency physicians to sit for the HPM board certification. This paved the way for interested emergency physicians to become dual board‐certified in EM and HPM. In 2019, over 150 dual board‐certified EM/HPM physicians exist, comprising approximately 2% of all HPM physicians.25

Then, in 2012, ACEP released its initial Choosing Wisely recommendations, which emphasized the importance of integrating palliative care into the ED. Among its five recommendations for best practices in EM, the Choosing Wisely recommendations stated, “Don’t delay in engaging available palliative and hospice services in the emergency department for patients likely to benefit.”26 The widely circulated Choosing Wisely recommendations, together with an emerging group of leaders in EM and palliative medicine, has led to accelerated change in EM practice and more widespread adoption of palliative care in the ED.

The present – training and quality improvement for palliative care in the ED

Primary vs. specialty palliative care for emergency physicians

As the population ages, the number of people living with serious illness is expanding. This has brought increased demand on the health system for the clinicians who can provide palliative care. Currently, the shortage of clinicians with palliative care training continues to increase.27, 28 In the face of this workforce shortage, the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care Medicine (AAHPM) has emphasized a delineation within palliative care practice, separating primary (i.e., basic) from specialty (i.e., complex) palliative care, with primary palliative care being carried out by non‐palliative clinicians.29 Meeting the needs of the seriously ill population means developing competency in primary palliative medicine across a broad array of medical specialties – particularly specialties such as EM, that have heavy contact with older adults and the seriously ill.

Because the imperative to educate the EM workforce in primary palliative care has only recently been established, most practicing EM clinicians have not had exposure to primary palliative care training.30 Thus, educational and training opportunities in primary palliative care have been developed specifically targeting practicing EM clinicians. Well‐established programs include CAPC’s IPAL‐EM program,21 and Northwestern University’s EPEC‐EM program.20 More recently, the Primary Palliative Care Education, Training, and Technical Support for Emergency Medicine (PRIM‐ER) trial brought training and education in palliative care to 33 EDs nationally, as part of a large cluster‐randomized, stepped wedge trial to measure the effect of primary palliative care education on older adults with serious illness.31 Additionally, state medical boards and hospital credentialing committees have begun to require physicians to complete 1–2 h of palliative or EOL care continuing medical education. Currently, five states require physicians to participate in palliative continuing medical education credits.32

Primary palliative care training in residency

Currently, the degree of primary palliative care training for EM residents is variable nationally. Several studies over the past decade have examined the need for this training. Lamba et al. in 2012 reported that, while 88% of EM residents agreed that palliative care skills were an important area of competency, roughly half of them reported having had minimal training.33 In 2016, Kraus et al. undertook a national survey of residency programs and found that only approximately half of the programs had any level of palliative care training for residents. A common barrier identified was lack of palliative expertise amongst teaching faculty. Not surprisingly, many surveyed felt uncomfortable leading challenging conversations or managing refractory symptoms.34

Most EM residency programs tailor their teaching to address the topics listed in “The Model of Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine,” which “serves as the basis for the content specifications for all ABEM examinations.” However, of the hundreds of topics currently listed across the 48+ pages in the guideline’s latest addition, only a handful are related to palliative care themes.

In 2018, a national committee of dual board‐certified EM/HPM experts developed and published a consensus piece defining content areas and competencies for primary palliative care in the emergency department setting. The group also developed milestones in the realm of palliative care in EM to identify relevant knowledge, skills, and behaviors using the framework modeled after the existing Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education EM milestones.35 Further work needs to be done to encourage and support residency programs in incorporating these (or similar) EM–palliative educational milestones and better equipping residents to provide primary palliative care.

Specialty palliative care training

As mentioned previously, fellowship training in HPM was made available for emergency physicians beginning in 2006. Fellowship‐trained physicians are able to work clinically in both the ED and palliative care. Beyond clinical work, dual board‐certified EM/HPM physicians have served in critical leadership roles at local and national levels (e.g., Dr. Tammie Quest, MD became the first emergency physician to be the President of AAHPM in 2019). Many dual board‐certified physicians spearhead primary palliative care trainings and local quality improvement initiatives that are critical to scaling up the EM response to the increasing palliative care needs of the population.

Quality improvement initiatives

Alongside clinical training in palliative care, an increasing number of quality improvement efforts are occurring in the ED using traditional quality improvement methods.36 These studies have elucidated some of the challenges of this work in EM, including staff turnover, the time constraints in EDs, and the challenges that older patients and their families face in trying to fully participate in co‐design.37 More recently, Wright et al. published a qualitative study of staff priorities for improving palliative care in the ED and identified eight challenges: (i) patient age, (ii) access to information, (iii) communication with patients, family members, and clinicians, (iv) understanding of palliative care, (v) role uncertainty, (vi) complex systems and processes, (vii) time constraints, (viii) limited training and education.38 Given these challenges, it is not surprising that the bulk of the work in improving the quality of palliative care delivery in the ED has focused on trying to improve patient access (e.g., triggered palliative care consultations), clinician’s primary palliative care skills, and create more streamlined processes.39, 40, 41 They have all shown to result in more frequent, timely, palliative care involvement in patients’ care after the ED.

The future – ongoing and future research

As palliative care in EM continues to mature, additional research is needed to help inform policy, develop novel interventions, create practice guidelines, and scale primary palliative care education. Key issues facing EM–palliative care researchers must be rigorously studied with outcomes that matter most to the patients.

Identifying patients who may benefit from palliative care

Accurate estimates of palliative care needs among ED patients are lacking. Large‐scale efforts at data collection quantifying this need have yet to be undertaken. One approach to quantifying the palliative care needs would involve the creation of a national registry. However, unlike similar registries tracking trauma incidence42 and cancer prevalence43 in the health system, the precise definition of a patient requiring palliative care has yet to be defined.44

Progress has been made towards identifying palliative care patients in the ED. Researchers have determined that palliative care screening in the ED is feasible using brief screening tools like Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening (P‐CaRES)45, 46 and Screen for Palliative and End‐of‐life care needs in the Emergency Department (SPEED).47 In addition, mortality‐based prediction could be used as an alternative method to identify patients who might benefit from palliative care. Quick and easy tools like the “surprise question,” worded as “would you be surprised if your patient died in the next one month?” has been used in the ED setting to identify patients with high near‐term mortality.48, 49 Prospective studies that determine the utility of these patient identification methods and associated outcomes are imperative to improving palliative care delivery in the ED. In the near future, we anticipate that health‐care systems across the USA will likely require a method to identify patients who would benefit from palliative care in the ED.

Implementation of primary palliative care in the ED

Incremental gains to improve access to palliative care in the ED must also occur concurrently to the identification pathways. Several ongoing studies are examining the effect of palliative care programs in the ED:

Primary Palliative Care for Emergency Medicine (PRIM‐ER): This cluster‐randomized, stepped wedge trial is testing the effectiveness of implementing primary palliative care in 33 EDs across the USA. The intervention includes four core components: (i) evidence‐based, multidisciplinary primary palliative care education, (ii) simulation‐based workshops, (iii) clinical decision support, (iv) audit and feedback. The study is divided into two phases: a pilot phase, to ensure feasibility in two sites, and an implementation and evaluation phase, where we implement the intervention and test the effectiveness in 33 EDs over 2 years. Using Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data, the primary outcomes in approximately 300,000 patients will be assessed: ED disposition to an acute care setting, health‐care utilization in the 6 months following the ED visit, and survival following the index ED visit. This trial is scheduled to complete in 2022.50

Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA): A prior randomized clinical trial found that ED‐initiated, inpatient palliative care consultation in advanced cancer improves quality of life and does not seem to shorten survival in patients with advanced cancer. Building on the prior trial, this multisite, cluster‐randomized, two‐arm clinical trial in ED patients compares two established models of palliative care: nurse‐led telephonic case management and specialty, outpatient palliative care. Seriously ill patients are being recruited at the time of ED discharge. The target outcomes include: (i) quality of life in patients, (ii) health‐care utilization, (iii) loneliness and symptom burden, (iv) caregiver strain, caregiver quality of life, and bereavement. This trial is scheduled to complete in 2023.31

Advance care planning (ACP) intervention in the ED. More than 70% of older adults prefer quality of life rather than life extension,9 yet a systematic review revealed that 56% to 99% do not have advance directives at the time of an ED visit51 and are at risk of receiving care inconsistent with their goals.52 To seize the opportunity of the ED visit to engage seriously ill older adults at a critical moment in their illness trajectory, a behavioral intervention to initiate/reintroduce ACP conversations has been developed. This intervention engages older adults in ACP conversations in the ED to overcome the known barriers to ACP in this setting (e.g., time constraints, limited privacy, uncertainty in patients’ awareness of their illness).30 Modeled from previously successful ED behavioral interventions,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 this intervention consists of a 6‐min motivational interview that allows ED clinicians to engage patients in thinking about the importance of addressing goals of care with their outpatient clinician, thus avoiding a more time‐consuming, sensitive conversation in the time‐pressured ED environment. Seriously ill older adults found it acceptable and motivated them to talk to their outpatient clinicians about their goals of care.59 The patient‐centered effects of this intervention are still being tested at this time.

As illustrated above, several approaches to improve primary palliative care skills and services are being tested in the ED setting. Identification of patients who would benefit from palliative care and care pathways or interventions to provide palliative care services will be the future of ED‐initiated palliative care in the USA (Fig. 1). The actual components of this future standard of care will depend largely on the results of above‐mentioned studies. In addition, under‐explored areas of research, such as the best practice and effect of hyperacute, crisis communication (i.e., a decision‐making conversation with clinically unstable patients with serious illness requiring urgent invasive intervention) are needed for further exploration. Regardless of current studies, more studies on palliative care interventions and services are required to improve the quality of care in the ED.

Figure 1.

Current and future palliative care in the emergency department (ED). Images created by Iconarray.com. Risk Science Center and Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan (Accessed 20 December 2019).

Disclosure

Approval of the research protocol: N/A.

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Funding Information

Sojourns Scholars Leadership Program, Cambia Health Foundation.

References

- 1. Chronic Disease Overview. 2009; http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm. Accessed 8/7, 2017.

- 2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: global burden of disease study. Lancet 1997; 349: 1269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chronic Care: Making the case for ongoing care. 2010; https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/. Accessed 12/1, 2018.

- 4. Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl. Health Stat. Report 2008; 7: 1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE et al Waits to see an emergency department physician: U.S. trends and predictors, 1997–2004. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2008; 27: w84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu KT, Nelson BK, Berk S. The changing profile of patients who used emergency department services in the United States: 1996 to 2005. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009;54:805–10 e801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E et al Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2012; 31: 1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernacki RE, Block SD. American College of Physicians High Value Care Task F. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014; 174: 1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000; 284: 2476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodman DC ea. Trends in Cancer Care Near the End of Life . Hanover, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Healthcare Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connors AF. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 1995; 274: 1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL et al Are regional variations in end‐of‐life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Med. Care. 2007; 45: 386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gindi RM, Black LI, Cohen RA. Reasons for emergency room use among U.S. Adults Aged 18–64: national health interview survey, 2013 and 2014. Natl. Health Stat. Report 2016; 18, 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J. Palliat. Med. 2013; 16: 1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aldridge MD, Bradley EH. Epidemiology and patterns of care at the end of life: rising complexity, shifts in care patterns and sites of death. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2017; 36: 1175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Field MJ, Cassel CK, Institute of Medicine (U.S.) . Committee on Care at the End of Life. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP et al Change in end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 2013; 309: 470–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NIH State‐of‐the‐science conference statement on improving end‐of‐life care. NIH Consens. State Sci. Statements 2004; 21: 1‐26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American College of Emergency P . Ethical issues at the end of life. Ann. Emerg .Med. 2008;52: 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. EPEC for Emergency Medicine . Education in Palliative and End of Life Care (EPEC) 2010; https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/curricula/emergency.html. Accessed 12/09, 2019.

- 21. Improving Palliative Care in Emergency Medicine. 2011; http://www.capc.org/ipal/ipal-em. Accessed 12/09, 2019.

- 22. Grudzen CR, Stone SC, Morrison RS. The palliative care model for emergency department patients with advanced illness. J. Palliat. Med. 2011; 14: 945–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Hopper SS, Ortiz JM, Whang C, Morrison RS. Does palliative care have a future in the emergency department? Discussions with attending emergency physicians. J. Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 43: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lamba S. Early goal‐directed palliative therapy in the emergency department: a step to move palliative care upstream. J. Palliat. Med. 2009; 12: 767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. A Profile of Active Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physicians , 2016. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 2017.

- 26. Phyisicians ACoE . Choosing Wisely Recommendations . American College of Emergency Phyisicians 2018.

- 27. Lupu D, American Academy of H , Palliative Medicine Workforce Task F . Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J. Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 40: 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, Salsberg ES. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J. Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013; 368: 1173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA et al Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009; 54: 86–93, 93 e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grudzen CR, Brody AA, Chung FR et al Primary palliative care for emergency medicine (PRIM‐ER): protocol for a pragmatic, cluster‐randomised, stepped wedge design to test the effectiveness of primary palliative care education, training and technical support for emergency medicine. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e030099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Advancing Palliative Care for Adults with Serious Illness: A National Review of State Palliative Care Policies and Programs. 2018; https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/NASHP_State-Palliative-Care-Scan_Appendix-A-New.pdf. Accessed 12/09, 2019.

- 33. Lamba S, Pound A, Rella JG, Compton S. Emergency medicine resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. J. Palliat. Med. 2012; 15: 516–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kraus CK, Greenberg MR, Ray DE, Dy SM. Palliative care education in emergency medicine residency training: a survey of program directors, associate program directors, and assistant program directors. J. Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 51: 898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shoenberger J, Lamba S, Goett R et al Development of hospice and palliative medicine knowledge and skills for emergency medicine residents: using the accreditation council for graduate medical education milestone framework. AEM Educ. Train 2018; 2: 130–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pines JM, Asplin BR. Systems Approach Conference P. Conference proceedings‐improving the quality and efficiency of emergency care across the continuum: a systems approach. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011; 18: 655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blackwell RW, Lowton K, Robert G, Grudzen C, Grocott P. Using Experience‐based Co‐design with older patients, their families and staff to improve palliative care experiences in the Emergency Department: A reflective critique on the process and outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017; 68: 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wright RJ, Lowton K, Robert G, Grudzen CR, Grocott P. Emergency department staff priorities for improving palliative care provision for older people: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2018; 32: 417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson JG, English DP, Owyang CG et al End‐of‐life care, palliative care consultation, and palliative care referral in the emergency department: a systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2019; 59: 372–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Quest T, Herr S, Lamba S, Weissman D, Board I‐EA. Demonstrations of clinical initiatives to improve palliative care in the emergency department: a report from the IPAL‐EM Initiative. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013; 61: 661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glajchen M, Lawson R, Homel P, Desandre P, Todd KH. A rapid two‐stage screening protocol for palliative care in the emergency department: a quality improvement initiative. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2011; 42: 657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Trauma Data Bank. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqp/center-programs/ntdb/about. Accessed 12/17, 2019.

- 43. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed 12/17, 2019.

- 44. Kelley AS, Bollens‐Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: The "Denominator" Challenge. J. Palliat. Med. 2018; 21(S2): S7–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. George N, Phillips E, Zaurova M, Song C, Lamba S, Grudzen C. Palliative Care screening and assessment in the emergency department: a systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 51: 108–19 e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bowman J, George N, Barrett N, Anderson K, Dove‐Maguire K, Baird J. Acceptability and reliability of a novel palliative care screening tool among emergency department providers. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016; 23: 694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Richards CT, Gisondi MA, Chang CH et al Palliative care symptom assessment for patients with cancer in the emergency department: validation of the Screen for Palliative and End‐of‐life care needs in the Emergency Department instrument. J. Palliat. Med. 2011; 14: 757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ouchi K, Strout T, Haydar S et al Association of emergency clinicians' assessment of mortality risk with actual 1‐month mortality among older adults admitted to the hospital. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019; 2: e1911139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ouchi K, Jambaulikar G, George NR et al The "Surprise Question" asked of emergency physicians may predict 12‐month mortality among older emergency department patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2018; 21: 236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Grudzen CR, Shim DJ, Schmucker AM, Cho J, Goldfeld KS, Investigators EM. Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA): protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of specialty outpatient versus nurse‐led telephonic palliative care of older adults with advanced illness. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e025692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oulton J, Rhodes SM, Howe C, Fain MJ, Mohler MJ. Advance directives for older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review. J. Palliat. Med. 2015; 18: 500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. O'Connor AE, Winch S, Lukin W, Parker M. Emergency medicine and futile care: Taking the road less travelled. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2011; 23: 640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict. Behav. 1996; 21: 835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. D'Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV et al A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012; 60: 181–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bernstein E, Edwards E, Dorfman D, Heeren T, Bliss C, Bernstein J. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009; 16: 1174–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005; 77: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bruguera P, Barrio P, Oliveras C et al Effectiveness of a specialized brief intervention for at‐risk drinkers in an emergency department: short‐term results of a randomized controlled trial. Acad. Emerg. Med 2018; 25: 517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sommers MS, Lyons MS, Fargo JD et al Emergency department‐based brief intervention to reduce risky driving and hazardous/harmful drinking in young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013; 37: 1753–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ouchi K, George N, Revette AC et al Empower seriously ill older adults to formulate their goals for medical care in the emergency department. J. Palliat. Med. 2018; 22: 267–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]