Abstract

Objectives

The lactase persistence/nonpersistence (LP/LNP) phenotypes follow a geographic pattern that is rooted in the gene-culture coevolution observed throughout the history of human migrations. The immense size and relatively open immigration policy have drawn migrants of diverse ethnicities to Canada. Among the multicultural demographic, two-thirds of the population are derived from the British Isles and northwestern France. A recent assessment of worldwide lactase distributions found Canada to have an LNP rate of 59% (confidence interval [CI] 44%–74%). This estimate is rather high compared with earlier reports that listed Canada as a country with a 10% LNP rate; the authors had also noted that biases were likely because their calculations were based largely on Aboriginal studies. We hereby present an alternate LNP prevalence estimate at the national, provincial and territorial level.

Methods

We applied the referenced LNP frequency distribution data to the 2016 population census to account for the current multi-ethnic distributions in Canada. Prevalence rates for Canada, the provinces and territories were calculated.

Results

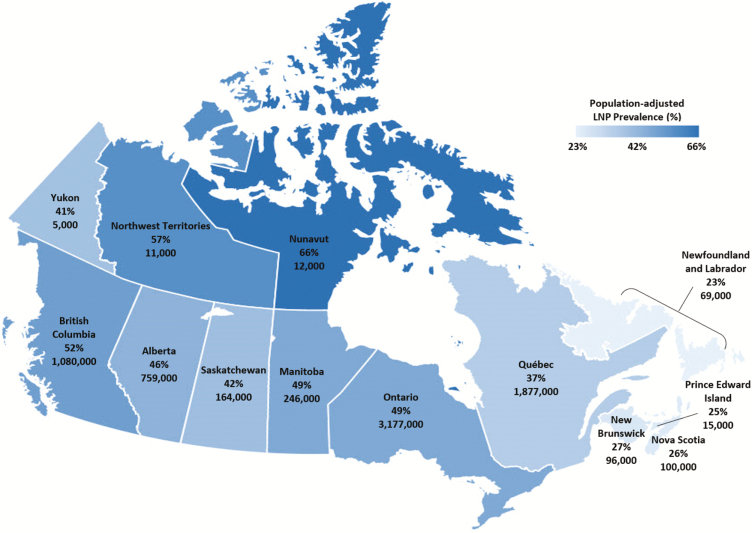

The national LNP rate is estimated at 44% (CI 41%–47%) after accounting for the 254 ethnic groups, with the lowest rates found in the eastern provinces and the highest rates in the Northwest Territories (57%) and Nunavut (66%), respectively.

Conclusion

Despite the heterogeneous nature of the referenced data and the inference measures taken, evidently, the validity of our LNP estimate is anchored on the inclusion of multi-ethnic groups representing the current Canadian demographic.

Keywords: Canadian census data, Demographic inference, Disease epidemiology, Lactase nonpersistent; Lactase persistent, Lactose intolerance

Milk provides optimal nutrition for neonatal growth and development. With lactose being the principal carbohydrate, its digestion is indispensable and mediated by the intestinal brush border enzyme lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) or lactase (LCT). While the ability to metabolize lactose is conserved among mammalian neonates, the vast majority loses such ability soon after weaning, with humans being the notable exception (1, 2). This gain-of-function ‘mutation’ is an inheritable autosomal dominant trait, associated with noncoding variation in the distal regulatory enhancer region ∼14 kb upstream of the LCT transcription site (3–5). The result is prolonged upregulation of LCT gene expression throughout adulthood.

Many Northern Europeans carry the −13910C>T (rs4988235) variant (TT), whereby a single T-allele change at position 13910 in intron 13 of the minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 (MCM6) gene contributes to their lactase persistence (LP) phenotype (3). Since then, four other genetic variants have been identified to have co-emerged across different geographical regions at various time points during the Neolithic revolution. Such parallel increase in the frequency of multiple alleles suggests strong cultural-historical selection pressure because it coincided with the adoption of pastoralism and milk consumption around 3000 to 7500 years ago (2, 6–11). To date, this evolutionary adaptation dichotomizes the global adult populations into one-third who are lactose digesters and the rest as homozygous ‘wild-types’ who are lactase nonpersistence (LNP) (1, 2).

While positive selection affects particular genes, geographic and demographic variables over time can exert a uniform effect on the genome which may become important under conditions of stress and disease. Occurrences of chronic disease, purportedly the result of ‘Western’ lifestyles and industrialization, have been described to follow a distinctive north-south gradient (12–17). Certain cancer types, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and autoimmune disorders also correlate with the national LP/LNP frequencies to some degree (18, 19). Although global LP/LNP prevalence remains relatively stable, the distribution of LP/LNP phenotypes can vary in response to human migratory patterns. Along with the changing lifestyles and dietary habits, it may be worthwhile to monitor the shifting dichotomy of LP/LNP distributions, particularly in once LP-dominant Western nations, and study the resulting health implications at the population level (20, 21). This is especially relevant for Canada.

Due to the immense geographic size and open immigration policy, present-day Canada is drawing migrants of diverse ethnic backgrounds, which, in variable numbers, reflects the global population. Among the 254 ethnic origins reported in the 2016 census (22), two-thirds of Canadians still identified themselves as being either British or French descendants of early colonial settlers (23, 24). The rest are partitioned into various demographic groups consisting of European, Asian, and, to a lesser extent, African and Middle Eastern, with a small percentage derived from North American Aboriginal (i.e., First Nations, Inuit and Métis). As such, the Canadian LP/LNP distribution profile has likely changed, and the extent of this change warrants further evaluation.

In a recent publication by Storhaug et al. on the global distributions of LNP frequencies, Canada was reported as having a 59% LNP prevalence (confidence interval [CI] 44%–74%) (25). This estimate is markedly higher compared with earlier studies listing Canadian LNP prevalence <10%, reflecting origins from northern Europe (26, 27). According to a 2013 nationwide online survey on self-reported lactose intolerance (LI) from 2251 responders, only 16% of the population conferred to LNP status (28). Furthermore, Storhaug et al. noted that an overestimation of LNP prevalence was likely because their sample data were based on outdated studies of Aboriginal populations (29, 30).

In an effort to obtain a more accurate LP/LNP distribution profile at the national level, we incorporated all ethnic categories provided by the latest 2016 population census into our sampled population. We then used Storhaug data of global LNP prevalence to derive LNP estimation rates for our Canadian demographic.

METHODS

Referenced Populations for Estimating National LNP Prevalence

National LNP prevalence was ascertained from the latest systematic review and meta-analysis study by Storhaug et al (25). Prevalence data from 175 studies were evaluated on lactose malabsorption (LM) or LP among adults and children age 10 years or older by means of standardized methods (i.e., genotyping, hydrogen breath tests or lactose tolerance tests). An 84% global population coverage based on 450 population groups of 89 countries was achieved. Despite heterogeneity between studies of the assessed countries, they reported a global LNP prevalence of 68% (CI 64%–72%), with Canada at 59% (CI 44%–74%).

Sampled Canadian Populations

Ethnic composition and total population of Canada were derived from the 2016 Census (22). The overall imputation rate for reported ethnic origin at the national level is 4.5%. With the exception of Aboriginals, many can relate their ethnic origins to the ancestral or cultural ‘roots’ independent of citizenship, nationality, language or birthplace. For instance, a naturalized Mauritian-born Canadian citizen, whose mother tongue is Punjabi but communicates in English and French, may report ‘East Indian’ as their ethnic identity. For more information on the collection, classification, dissemination and quality assessment of the ethnic origin data, consult the Ethnic Origin Reference Guide (31).

LNP Inference Measures

Because LNP prevalence was only available for 89 countries while a total of 254 ethnic groups were reported in the 2016 Census, several strategies were employed to facilitate comparisons between the referenced and sampled populations. First, similar ethnic groups were further combined into broader ethnic categories, such as the case of ‘Channel Islander,’ ‘Cornish,’ ‘English,’ ‘Manx,’ ‘Scottish’ and ‘Welsh.’ Together, they were categorized under ‘United Kingdom’ with an assigned 0.08 LNP frequency (25). Similarly, for countries that were previously assessed but were not a stand-alone ethnic group in the census report, we included their corresponding prevalence data when calculating the averaged LNP frequencies of broad regional categories such as ‘Other Southern and East African origins.’

Secondly, because LNP is a genotypic attribute, in the absence of referenced data LNP frequencies were imputed according to the predominant genomic contribution of ancestral donor populations. Owing to past intercontinental admixture events, the contemporary Caribbean populations exhibit a high degree of parental lineages from West Central Africa and Northern Europe regions (32). Thereby, we inferred that the LNP prevalence in connection to the Caribbean heritage was the weighted arithmetic mean of LNP frequencies for ‘United Kingdom,’ ‘Ireland,’ ‘France,’ ‘Spain’ and ‘West Central Africa,’ respectively.

Similar inference measures were taken for the contemporary North American cohorts, many of which still share comparable genetic signature with their parental European counterparts (33–35). According to ancestral admixture analyses, noncolonial immigrants of various origins had very limited genetic impact on the French Canadian population (36), with ∼90% of the French Canadian gene pools still contributed to by the original French settlers (37). We assigned the referenced 0.36 LNP estimate of France for ‘Québécois.’ The ‘Acadian’ populations, despite being mostly of French origin, have interbred to varying degrees with the Aboriginal people. Hence, we estimated that the corresponding LNP frequency would be equally contributed by those two groups. Consistent with the population immigration history, the genetic substructure within ‘Newfoundlanders’ resembles that of the British population (i.e., ‘English,’ ‘Irish,’ ‘Scottish’) with other contributions from ‘North American Aboriginal’ and ‘French’ (34). We performed a weighted average of LNP rates in reference to those five genetic contributions. For the broadly identified ‘Canadian’ and ‘Other North American origins’ groups, we simply inferred that their LNP frequency be the weighted LNP rates for the most frequently identified ‘founder origins’ (similar to that of ‘Newfoundlanders’).

Although the demographic and evolutionary complexity of Native American populations is beyond our scope (38, 39), our inference approach was consistent with the major genomic signatures imprinted in contemporary ‘North American Aboriginals’ living in Canada. These include present-day western Eurasians (i.e., West Central Asia/Middle East region and to some extent Mongolia), English and French but not East Asians (38).

Data Analyses

Before deriving an estimated LNP for Canada (and its territories/provinces), the total ethnic population (Pe) was calculated using census dataset

| (1) |

where Ei is the number of responses of a reported ethnicity at the national or territorial/provincial level, and n represents the number of ethnic groups.

Next, the total LNP prevalence (PLNP) was determined by

| (2) |

where LNPi corresponds to the referenced or inferred LNP frequency for each ethnic origin.

Finally, the weighted LNP prevalence estimate (in percentage) was derived as follows:

| (3) |

It is important to note that Pe and the total national population are not equivalent, with Pe surpassing the latter due to individuals reporting multiple ethnic origins. We decided to exclude those people who have multiple origins because it is unknown whether a person is 50% Italian and 50% French, or 25% Italian and 75% French, if this person reported having both Italian and French origins. Without this distribution, it is impossible to accurately determine the LNP status of such an individual. Moreover, in order to correspond with the age cutoff of Storhaug study populations, we included only individuals age 15 years and above. Therefore, our study population consisted of Canadians 15 years old and above who identified themselves with only one ethnic origin as reported in the census. Estimated LNP prevalence for Canada and for its provinces/territories were provided, along with their 95% confidence intervals (P < 0.05). Confidence intervals were calculated by incorporating LNP prevalence estimates in the various ethnic subgroups. All data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and statistical software package SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, NC).

RESULTS

From the 2016 nationwide census, the total national population was estimated at 35,151,728. After ethnic stratification (31), the population count became 34,460,065, of which there were 20,297,880 (59%) responders who reported only one ethnic origin out of the 254 ethnic groups. Following the age exclusion of those less than 15 years old, we finalized our study population to be 17,324,085 (Eq. 1). Table 1 shows the number and percentage of age-adjusted single ethnic responders by geographic region in comparison with the entire mono-ethnic population. After applying the appropriate LNP frequency to each ethnic origin (Eq. 2), we estimated the national LNP prevalence as 44% (CI 41%–47%) (Eq. 3). Estimated LNP prevalence for each province/territory is listed in Table 2. Figure 1 is a graphical representation of the LNP distribution (per cent rate) across all territories and provinces within Canada. For a complete list of the 254 ethnic groups within the single responders, see the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Number and percentage of age-adjusted single ethnic responders (age ≥15) by geographic region versus the non-age-adjusted population. Population counts were provided by Statistics Canada (23)

| Single Ethnic Responders, Age ≥15 | Single Ethnic Responders, All Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Yukon | 12,340 | 0.07 | 14,355 | 0.07 |

| Northwest Territories | 19,385 | 0.11 | 23,945 | 0.12 |

| Nunavut | 18,930 | 0.11 | 28,115 | 0.14 |

| British Columbia | 2,076,255 | 11.98 | 2,371,215 | 11.68 |

| Alberta | 1,651,025 | 9.53 | 1,994,190 | 9.82 |

| Saskatchewan | 391,450 | 2.26 | 481,290 | 2.37 |

| Manitoba | 501,720 | 2.90 | 614,295 | 3.03 |

| Ontario | 6,483,555 | 37.43 | 7,534,635 | 37.12 |

| Québec | 5,073,910 | 29.29 | 5,976,810 | 29.45 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 300,035 | 1.73 | 344,185 | 1.70 |

| New Brunswick | 354,850 | 2.05 | 409,290 | 2.02 |

| Prince Edward Island | 58,115 | 0.34 | 67,610 | 0.33 |

| Nova Scotia | 382,515 | 2.21 | 437,945 | 2.16 |

| Total | 17,324,085 | 100.00 | 20,297,880 | 100.00 |

Table 2.

Estimated LNP prevalence for Canada and for each territory/province according to Storhaug data and inferred methods (25)

| Region | LNP Prevalence | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yukon | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.45 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.60 |

| Nunavut | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| British Columbia | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.56 |

| Alberta | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.46 |

| Manitoba | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.52 |

| Ontario | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| Québec | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.39 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| New Brunswick | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| Canada | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.47 |

Figure 1.

Territorial/provincial distribution of age-adjusted LNP prevalence (per cent rate) in Canada. Per cent rates are derived from single-ethnic responders rounded to the nearest 1000 persons for each province and territory.

DISCUSSION

This study is to put LNP prevalence of Canada in perspective with the recent assessment that evaluated LNP frequencies for 89 countries (25). Although actual figures of LP/LNP distributions have never been systematically examined, the national LNP rate should correlate inversely with the TT genotype of colonial European settlers from the British Isles and northwestern France (23, 24). To date, their descendants, known as the ‘founder populations,’ make up approximately two-thirds of the national population (22). Nevertheless, a shift in migratory patterns in the last two decades has slowly replaced natural increase as the main source of population growth (40), owing to low fertility and population aging (41). By including all major and minor ethnic groups identified by the 2016 census, we expect that the estimated national LNP prevalence will help further assess dairy product nutrition in the population and track patterns of diseases putatively linked with LCT trait distributions. While this methodology has inherent inaccuracies, previous studies have used polymorphic traits to estimate phenotypic status on a population basis. The most relevant to our study is the evaluation of the drug-metabolizing enzyme CYP2D6 of the cytochrome P450 gene superfamily (42). Here, the authors compiled global CYP2D6 allele-frequency data, in a similar manner to the LCT gene, for the estimation and comparison of drug metabolizing status within and among ethnic groups. Remarkably, both CYP2D6 and LCT analyses highlight the challenges of deriving phenotype status from genotype data. Allelic variants considered rare, less frequent or novel might elude detection, which can lead to their miscategorization as the interrogated alleles by default. Hence, the predicted prevalence and reported frequencies of certain phenotypes might differ between populations of similar ethnic backgrounds and within the major ethnic groups (42). Other genetic factors such as distant enhancer SNP expression and sequence variations can also impact gene expression, thus altering individual metabolic capacity, resulting in a phenotype that no longer corresponds to the expected genetic profile. Lastly, the inclusion of phenotype studies not based on genotype data can also account for the difference between predicted and observed phenotypes, as is the case with CYP2D6 and LCT.

In our study, the national LNP rate is estimated at 44% after accounting for the 254 ethnic groups. The lowest rates are in the eastern provinces, while the highest are in the Northwest Territories (57%) and Nunavut (66%), respectively (Table 2; Figure 1). Here the population is predominantly Aboriginal. Genetic admixture analyses have confirmed that the North American Aboriginal group consists of two population substructures: one ancestral to East Asians and the other to western Eurasians (38, 39), where admixture events had likely occurred before their migration to the Americas during the Pleistocene epoch (39). It is expected that at the individual level, those coming from admixed lineage of different ancestral origins can confound the accuracy in predicting present-day LNP status. Mendelian distribution predicts that in intermarriage between individuals of differing LP/LNP status, at least half or more offspring will possess an LP phenotype. While this is noted among the Aboriginal populations like the Métis, the impact of intermarriage on LP/LNP status makes it difficult to determine the phenotypic trait in other ethnic groups without conducting LCT genetic tests.

There are two major consequences associated with LNP. First, LNP individuals generally consume less dairy (18, 43–45), and second, they may experience digestive symptoms due to periodic consumption of lactose. Adult-onset LNP phenotype is interchangeably defined with other terms such as adult hypolactasia, primary acquired lactase deficiency (LD) and lactose malabsorption (LM), with LM being most commonly used to describe LNP (Table 3). According to the 2010 NIH Consensus Conference, by definition, lactose intolerance (LI) refers to ‘the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., bloat, flatus, cramps, nausea, diarrhea) (46, 47) following a blinded, single-dose challenge of ingested lactose by an individual with lactose malabsorption, which are not observed when the person ingests an indistinguishable placebo (48).’ In other words, LI can occur regardless of LNP status. Unlike LI, in many cases LM does not come to clinical attention because the development and degree of symptoms are governed by multiple biological and individual factors: (1) lactose load (46, 47), (2) oro-cecal transit time, (3) net food intake (e.g., meals with higher fat content or osmolality can delay gastric emptying, as opposed to an empty stomach) (49–51), (4) composition and fermentation capacity of colonic microbiota (52), (5) regular intake of dairy products (i.e., promote microbiota diversity including Bifidobacterium) (46, 53, 54), (6) sensitivity threshold to increased osmotic load of unabsorbed lactose (i.e., gut distension due to excess fluid/gaseous secretion), (7) intermediate levels of LCT activity among heterozygous (CT) individuals, and finally (8) psychological perception (e.g., visceral hypersensitivity) (55).

Table 3.

Definition of lactose- and lactase-related concepts

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Lactase persistence (LP) | Persistence of high lactase expression activity at the jejunal brush border into adulthood, resulting in individuals with the ability to digest lactose beyond weaning phase |

| Lactase nonpersistence (LNP) | The natural decline in lactase expression activity at the jejunal brush border post- weaning, resulting in some individuals experiencing symptoms due to minimal ability to digest lactose |

| Estimated lactase persistence (LP) and lactase nonpersistence (LNP) rates | Percentages of population according to lactose digestion status as determined by combined measurements of indirect (e.g., breath hydrogen, blood glucose, or urinary galactose excretion following lactose challenge) and direct genotyping methods. The latter evaluates the expression levels of lactase (LCT) polymorphic variants which can be used to differentiate among homozygous digesters, maldigesters, and heterozygous persons with intermediate LCT activity |

| Lactose malabsorption (LM) | Inefficient or incomplete digestion of lactose due to LNP (primary) or other intestinal pathologies (secondary) |

| Lactose intolerance (LI) | Gastrointestinal symptoms presented in individuals with LM, including flatus, gas, bloating, cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting (rarely) |

| Lactose sensitivity | Systemic symptoms (e.g., nausea, depression, headache, fatigue) with or without the presence of LI symptoms |

| Lactase deficiency (LD) | Reduction of intestinal LCT expression activity due to either genetic or secondary causes such as diseases or injury to the proximal small bowel mucosa |

False preconceptions and the general lack of public understanding in lactose-related disorders warrant discussion, as well. From a clinical perspective, establishing individual LP/LNP phenotype should correlate with lactose driven symptoms, in which the primary goal is to determine tolerance rather than etiology. This is highlighted in subjects with functional bowel diseases who demonstrated abnormal lactose and lactulose breath test results but were not true lactose malabsorbers (LNP) (56, 57). In this case, LI is not due to LCT deficiency but related to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), whereby the lactose substrate is prematurely exposed to excessive bacteria otherwise not found in the small bowel before it can be properly digested and absorbed.

Avoidance of lactose ingestion can also be inherent to culturally based attitudes toward dairy products. This is of particular concern among countries with a high prevalence of LNP, in which the combination of cultural practices and fear of developing abdominal symptoms may be barriers to regular dairy intake (18). Among the ethnic minority groups living in North America, the average dairy intakes are generally below that of the daily requirements. Avoidance could put them at increased risk for inadequate bone accrual, osteoporosis, and other adverse health outcomes (21, 48, 58, 59). This is because restricting dairy also subsequently limits the intake of other essential nutrients including calcium, potassium, phosphorus, vitamins A, D and B12, riboflavin, niacin, and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) (21, 48, 59). Over the past two decades, there has been a steady decline of approximately 28% in fluid milk consumption per capita among Canadians (60). Alternatively, consumer interest in other dairy products has seen a dramatic shift in recent years, reporting an overall increase of 109% in yogurt alone (61). Several studies published in Canada have shown improved nutritional outcomes in terms of calcium intake and bone health in connection with regular dairy intake among school children and elderly adults (62, 63). In summary, reduction of lactose intake rather than exclusion should be encouraged because, regardless of actual or perceived LI, most individuals demonstrate tolerance for at least one glass of milk daily (12.5g lactose) (64), and threshold for lactose-induced symptoms can be doubled (up to 24 g) if taken with a meal (49–51). We previously conducted a nutrigenetic meta-analysis study where we examined national dairy intake and incidence of colorectal cancer (65). According to our analysis, a protective role of higher dairy intake was observed in both LP- and LNP-prevalent populations. In other words, the potential anticolorectal cancer benefits associated with dairy foods are independent of LP status and also extend to those who are lactose maldigesters. Several studies have also supported the beneficial impact of low-fat dairy consumption on reducing colorectal cancer risk (66) and other chronic disease risks including hypertension and cardiovascular-related complications (67, 68) and the lesser-known association IBD (69).

Our study has several methodology limitations in relation to the census data, which have undergone random rounding, data suppression and other aspects of disclosure control (70). Because of random rounding, counts and percentages may vary slightly between different census datasets (i.e., total national population counts differ between datasets). Furthermore, there is a fundamental difference between census counts and population estimates. While the population census was designed to conduct a complete count of the population, inevitably some individuals were not enumerated (undercoverage), whereas others may be enumerated more than once (overcoverage). Lastly, Storhaug data represent a combined meta-analysis of genetic, biochemical and endoscopic research with variable methodologies. Because the primary raw data and detailed summary statistics were not provided, an additional sensitivity analysis (i.e., forest plots) could not be performed on the referenced populations to reassess and adjust for baseline characteristic imbalance.

While our methods described here are theoretically sound and the topic is broadly relevant, the presented research is—at best—an understudy to existing population-based genetic association studies. We hope our updated LNP prevalence data will provide a launching point for discussion and research interest to gather more genetic, biochemical and endoscopic data across the Canadian demographic. Until more thorough phenotypic data become available, we are limited to infer the national LNP status based on composite research investigations. Ideally, combinations of breath testing, lactose (glucose) blood tests and lactase genotyping of different populations in Canadian regions can more accurately reflect lactase distributions. Prospectively, the ethnic background of persons undergoing testing could be added to the clinical information. This knowledge would help to build population data on ethnic groups living in Canada. The value of this information can be used broadly for designing treatment, specifically for lactose-induced digestive and perhaps systemic symptoms. In addition, accurate lactase distributions allow more precise epidemiological studies that could relate diseases to lactase status.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology online.

Acknowledgements and Funding Sources

The authors would like to thank Neil Edelman and Sophia Nicole Ir (consulting analyst from Statistics Canada) for their insightful comments and help in data analyses, Professor Brian Smith (Desautels Faculty of Management, McGill University) for discussions on population calculations and finally to Charlotte Golden for her help with literature search. This work was not supported by any funding sources.

References

- 1. Swallow DM. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annu Rev Genet 2003;37:197–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ingram CJ, Mulcare CA, Itan Y, et al. Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence. Hum Genet 2009;124(6):579–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, et al. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat Genet 2002;30(2):233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Y, Harvey CB, Pratt WS, et al. The lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is controlled by a cis-acting element. Hum Mol Genet 1995;4(4):657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olds LC, Sibley E. Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: Functional role as a cis regulatory element. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12(18):2333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ingram CJ, Elamin MF, Mulcare CA, et al. A novel polymorphism associated with lactose tolerance in Africa: Multiple causes for lactase persistence?Hum Genet 2007;120(6):779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bersaglieri T, Sabeti PC, Patterson N, et al. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74(6):1111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poulter M, Hollox E, Harvey CB, et al. The causal element for the lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is located in a 1 Mb region of linkage disequilibrium in Europeans. Ann Hum Genet 2003;67(Pt 4):298–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enattah NS, Trudeau A, Pimenoff V, et al. Evidence of still-ongoing convergence evolution of the lactase persistence T-13910 alleles in humans. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81(3):615–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Ranciaro A, et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat Genet 2007;39(1):31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ranciaro A, Campbell MC, Hirbo JB, et al. Genetic origins of lactase persistence and the spread of pastoralism in Africa. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94(4):496–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moukayed M, Grant WB. The roles of UVB and vitamin D in reducing risk of cancer incidence and mortality: A review of the epidemiology, clinical trials, and mechanisms. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017;18(2):167–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grant WB. Roles of solar UVB and vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and increasing survival. Anticancer Res 2016;36(3):1357–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Leeuwen MT, Turner JJ, Falster MO, et al. Latitude gradients for lymphoid neoplasm subtypes in Australia support an association with ultraviolet radiation exposure. Int J Cancer 2013;133(4):944–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohr SB, Garland CF, Gorham ED, et al. Ultraviolet B and incidence rates of leukemia worldwide. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simpson S Jr, Blizzard L, Otahal P, et al. Latitude is significantly associated with the prevalence of multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82(10):1132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Rhee H, Coebergh JW, de Vries E. Is prevention of cancer by sun exposure more than just the effect of vitamin D? A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Eur J Cancer 2013;49(6):1422–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shrier I, Szilagyi A, Correa JA. Impact of lactose containing foods and the genetics of lactase on diseases: An analytical review of population data. Nutr Cancer 2008;60(3):292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Szilagyi A, Leighton H, Burstein B, et al. Latitude, sunshine, and human lactase phenotype distributions may contribute to geographic patterns of modern disease: The inflammatory bowel disease model. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:183–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang Q, Lin SL, Au Yeung SL, et al. Genetically predicted milk consumption and bone health, ischemic heart disease and type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2017;71(8):1008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thorning TK, Raben A, Tholstrup T, et al. Milk and dairy products: Good or bad for human health? An assessment of the totality of scientific evidence. Food Nutr Res 2016;60:32527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The 2016 Census of Population. Ethnic Origin for the Population in Private Households. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Released November 29, 2017. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (Accessed December 1, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wells RV. Population of the British Colonies in America Before 1776: A Survey of Census Data. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris C. The French background of immigrants to Canada before 1700. Cahiers de géographie du Québec 1972;16:313–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Storhaug CL, Fosse SK, Fadnes LT. Country, regional, and global estimates for lactose malabsorption in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2(10):738–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cramer DW. Lactase persistence and milk consumption as determinants of ovarian cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130(5):904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scrimshaw NS, Murray EB. The acceptability of milk and milk products in populations with a high prevalence of lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;48(4 Suppl):1079–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barr SI. Perceived lactose intolerance in adult Canadians: A national survey. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2013;38(8):830–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ellestad-Sayed JJ, Haworth JC. Disaccharide consumption and malabsorption in Canadian Indians. Am J Clin Nutr 1977;30(5):698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leichter J, Lee M. Lactose intolerance in Canadian West Coast Indians. Am J Dig Dis 1971;16(9):809–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. The 2016 Census of Population. Ethnic Origin Reference Guide. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Released October 25, 2017. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/guides/008/98-500-x2016008-eng.cfm (Accessed December 1, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moreno-Estrada A, Gravel S, Zakharia F, et al. Reconstructing the population genetic history of the Caribbean. PLoS Genet 2013;9(11):e1003925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gauvin H, Moreau C, Lefebvre JF, et al. Genome-wide patterns of identity-by-descent sharing in the French Canadian founder population. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22(6):814–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhai G, Zhou J, Woods MO, et al. Genetic structure of the Newfoundland and Labrador population: Founder effects modulate variability. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24(7):1063–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haines MR, Steckel RH.. A Population History of North America. Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vézina H, Tremblay M, Desjardins B, et al. Origines et contributions génétiques des fondatrices et des fondateurs de la population québécoise. Cahiers québécois de démographie 2005;34:235–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Low-Kam C, Rhainds D, Lo KS, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in French Canadians from Quebec. Hum Genet 2016;135(11):1213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raghavan M, Skoglund P, Graf KE, et al. Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature 2014;505(7481):87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moreno-Mayar JV, Potter BA, Vinner L, et al. Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans. Nature 2018;553(7687):203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The 2016 Census of Population. Canadian Demographics at a Glance. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Released February 19, 2016. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/access_acces/alternative_alternatif.action?l=eng&loc=/pub/91-003-x/91-003-x2014001-eng.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41. The 2016 Census of Population. Immigration and Diversity: Population Projections for Canada and its Regions, 2011 to 2036. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (Demosim team), Released January 25, 2017. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-551-x/91-551-x2017001-eng.htm (Accessed December 1, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gaedigk A, Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Prediction of CYP2D6 phenotype from genotype across world populations. Genet Med 2017;19(1):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Almon R, Sjöström M, Nilsson TK. Lactase non-persistence as a determinant of milk avoidance and calcium intake in children and adolescents. J Nutr Sci 2013;2:e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lember M, Torniainen S, Kull M, et al. Lactase non-persistence and milk consumption in Estonia. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12(45):7329–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morales E, Azocar L, Maul X, et al. The European lactase persistence genotype determines the lactase persistence state and correlates with gastrointestinal symptoms in the Hispanic and Amerindian Chilean population: A case-control and population-based study. BMJ Open 2011;1(1):e000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levitt M, Wilt T, Shaukat A. Clinical implications of lactose malabsorption versus lactose intolerance. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47(6):471–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hertzler SR, Huynh BC, Savaiano DA. How much lactose is low lactose?J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96(3):243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, et al. NIH consensus development conference statement: Lactose intolerance and health. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2010;27:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, et al. Lactose intolerance in adults: Biological mechanism and dietary management. Nutrients 2015;7(9):8020–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bedine MS, Bayless TM. Intolerance of small amounts of lactose by individuals with low lactase levels. Gastroenterology 1973;65(5):735–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shaukat A, Levitt MD, Taylor BC, et al. Systematic review: Effective management strategies for lactose intolerance. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(12):797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao J, Fox M, Cong Y, et al. Lactose intolerance in patients with chronic functional diarrhoea: The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31(8):892–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Szilagyi A. Adaptation to lactose in lactase non persistent people: Effects on intolerance and the relationship between dairy food consumption and evalution of diseases. Nutrients 2015;7(8):6751–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA. Colonic adaptation to daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;64(2):232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tomba C, Baldassarri A, Coletta M, et al. Is the subjective perception of lactose intolerance influenced by the psychological profile?Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36(7):660–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pimentel M, Kong Y, Park S. Breath testing to evaluate lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome correlates with lactulose testing and may not reflect true lactose malabsorption. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(12):2700–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vernia P, Di Camillo M, Marinaro V. Lactose malabsorption, irritable bowel syndrome and self-reported milk intolerance. Dig Liver Dis 2001;33(3):234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Casellas F, Aparici A, Pérez MJ, et al. Perception of lactose intolerance impairs health-related quality of life. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016;70(9):1068–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bonjour JP, Kraenzlin M, Levasseur R, et al. Dairy in adulthood: From foods to nutrient interactions on bone and skeletal muscle health. J Am Coll Nutr 2013;32(4):251–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. The Canadian Dairy Information Centre. Per Capita Consumption of Fluid Milk and Cream (Annual). Ottawa, ON: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Released March 23, 2018. www.dairyinfo.gc.ca/pdf/camilkcream_e.pdf (Accessed September 6, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 61. The Canadian Dairy Information Centre. Per Capita Consumption of Dairy Products in Canada (Annual). Ottawa, ON: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Released March 23, 2018. http://www.dairyinfo.gc.ca/pdf/dpconsumption_e.pdf (Accessed September 6, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ransome K, Rusk J, Yurkiw MA, et al. A school milk promotion program increases milk consumption and improves the calcium and vitamin D intakes of elementary school students. Can J Diet Pract Res 1998;59(4):70–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Barr SI, McCarron DA, Heaney RP, et al. Effects of increased consumption of fluid milk on energy and nutrient intake, body weight, and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100(7):810–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N Engl J Med 1995;333(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Szilagyi A, Nathwani U, Vinokuroff C, et al. The effect of lactose maldigestion on the relationship between dairy food intake and colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Nutr Cancer 2006;55(2):141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS, et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol 2012;23(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Drouin-Chartier JP, Brassard D, Tessier-Grenier M, et al. Systematic review of the association between dairy product consumption and risk of cardiovascular-related clinical outcomes. Adv Nutr 2016;7(6):1026–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aljuraiban GS, Stamler J, Chan Q, et al. ; INTERMAP Research Group Relations between dairy product intake and blood pressure: The INTERnational study on MAcro/micronutrients and blood Pressure. J Hypertens 2018;36(10):2049–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Opstelten JL, Leenders M, Dik VK, et al. Dairy products, dietary calcium, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a european prospective cohort investigation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22(6):1403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. The 2016 Census of Population. Guide to the Census of Population. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Released February 8, 2017. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/98–304/index-eng.cfm (Accessed December 1, 2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.