Abstract

Objective

To study the association of caregiver factors and stroke survivor factors with supervised community rehabilitation (SCR) participation over the first 3 months and subsequent 3 to 12 months post-stroke in an Asian setting.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Community setting.

Participants

We recruited stroke survivors and their caregivers into our yearlong cohort. Caregiver and stroke survivor variables were collected over 3-monthly intervals. We performed logistic regression with the outcome variable being SCR participation post-stroke.

Outcome measures

SCR participation over the first 3 months and subsequent 3 to 12 months post-stroke

Results

251 stroke survivor-caregiver dyads were available for the current analysis. The mean age of caregivers was 50.1 years, with the majority being female, married and co-residing with the stroke survivor. There were 61%, 28%, 4% and 7% of spousal, adult-child, sibling and other caregivers. The odds of SCR participation decreased by about 15% for every unit increase in caregiver-reported stroke survivor’s disruptive behaviour score (OR: 0.845; 95% CI: 0.769 to 0.929). For every 1-unit increase in the caregiver’s positive management strategy score, the odds of using SCR service increased by about 4% (OR: 1.039; 95% CI: 1.011 to 1.068).

Conclusion

We established that SCR participation is jointly determined by both caregiver and stroke survivor factors, with factors varying over the early and late post-stroke period. Our results support the adoption of a dyadic or more inclusive approach for studying the utilisation of community rehabilitation services, giving due consideration to both the stroke survivors and their caregivers. Adopting a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach in practice settings should include promotion of positive care management strategies, comprehensive caregiving training including both physical and behavioural dimensions, active engagement of caregivers in rehabilitation journey and conducting regular caregiver needs assessments in the community.

Keywords: rehabilitation medicine, stroke, social medicine, public health, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We studied the association of caregiver factors along with stroke survivor factors with supervised community rehabilitation participation over the first 3 months and subsequent 3 to 12 months post-stroke in a prospective yearlong cohort study.

We are among the first to demonstrate the role of caregivers in stroke survivor’s supervised community rehabilitation substantiating the rationale for the adoption of a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach to studying post-stroke outcomes.

Another strength is the comprehensiveness of caregiver variables considered, which enabled us to explore the role of caregivers in depth.

Our study sample included patients with stroke surviving the first post-stroke year, excluding deaths within the follow-up period (<5%) limiting the generalisability of our findings to those stroke survivors who are alive at the end of the first year post-stroke.

There is a possibility of information bias related to the limited recall of supervised community rehabilitation participation by stroke survivors and their caregivers, which was addressed by keeping a relatively shorter recall period.

Introduction

Stroke is associated with a significant mortality burden globally.1 However, recent epidemiological trends with an increased incidence in the younger population and decreasing mortality rates over the years highlight the importance of functional recovery post-stroke.2 While rehabilitation is essential for functional recovery and re-integration back in the community, it is conditional on patients with stroke taking the initiative to attend such rehabilitation services post-stroke. The transition from inpatient settings into the community is challenging for the stroke survivor-caregiver dyads.3 They move from a well-supported setting with a multidisciplinary team providing care and facilitating rehabilitation to a setting where they are on their own trying to maintain the care continuum and seeking community services including supervised community rehabilitation (SCR). This challenging transition is further described by the concept of the duality of stroke crisis with first crisis coinciding with the stroke and the second occurring during the discharge from an inpatient setting to home.4 During this second crisis, stroke survivors often feel unprepared and overwhelmed to navigate post-stroke recovery journey. Many stroke survivors rely on family caregivers’ assistance to continue their recovery journey.

The role of family caregivers becomes highly relevant post-stroke, considering more than half of the stroke survivors are discharged home with differing degrees of residual physical impairments.5 However, neither is this caregiving role explicitly acknowledged nor is the caregiver’s capacity and commitment to providing care assessed.6 This could result in a mismatch between the expected caregiving responsibilities and the caregiver’s ability to fulfil these, potentially leading to adverse consequences for the stroke survivor-caregiver dyad. High reliance on caregivers to assist the stroke survivors in the community implies that caregiver factors like coping or perceived stress can in turn, influence the stroke survivors’ outcomes like participation in SCR. This highlights the importance of adopting a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach to studying and implementing SCR, which includes provision of physical rehabilitation services by licensed physiotherapists or occupational therapists in the community settings, such as day rehabilitation centres (DRCs) or patient’s home. Dyadic approach is described as a ‘holistic approach to post-stroke care provision by healthcare practitioners, giving due importance to both patients with stroke and their caregivers, integrating caregivers in the healthcare system to extend the care continuum to include informal care in the community and provision of timely support for caregivers’.7 Prior accounts in both stroke7–10 and non-stroke11–13 populations have included such dyadic approach in their narratives. In addition, giving due consideration to both the stroke survivors and their caregivers in psychoeducational, skill-building and support interventions is reported to improve stroke survivors’ outcomes.8

Recognising the relevance of caregivers in stroke survivor’s recovery process, researchers have attempted to study the association of caregiver availability and some socio-demographic characteristics with functional outcomes post-stroke across inpatient rehabilitation services.14–18 While a study in the USA19 reported positive role of the spouse in the recovery of stroke survivors, another study in Canada15 reported caregiver support being associated with a higher functional gain as compared with those without caregiver support. A recent study in China explored the role of family member’s positive and negative attitudes in the functional and cognitive recovery of stroke survivors, with higher positive attitudes being associated with higher cognitive gains after rehabilitation.20 Existing literature supports caregivers playing an important role in stroke survivors’ functional and cognitive outcomes post-rehabilitation across different settings and contexts. However, none of the studies so far have focussed on the association of caregiver characteristics with SCR participation.

Addressing the above mentioned gaps, we aimed to study the association of caregiver factors along with stroke survivor factors with SCR participation over the first 3 months and subsequent 3 to 12 months post-stroke in an Asian setting.

Materials and methods

Study setting

In Singapore, after stabilisation in a tertiary hospital, stroke survivors are assessed for rehabilitation eligibility, and based on this assessment, they may undergo intensive rehabilitation in an inpatient setting.21 Another option either in succession to above or as an alternative is SCR, often delivered at the DRCs. DRCs are run either within the premises of a step-down facility or as stand-alone centres, mainly providing physiotherapy and occupational therapy.22 DRCs along with nursing homes (ie, long-term residential care settings within the community) and home-based rehabilitation fall under the broad umbrella of SCR.

Participants

Our participants were part of the Singapore Stroke Study (S3), a prospective observational study with recruitment of stroke survivors and caregivers over a period extending from December 2010 to September 2013. Singaporeans or permanent residents 40 years and above who suffered a stroke or experienced symptoms within 4 weeks of admission to any of the five tertiary hospitals in Singapore during the recruitment period with confirmed stroke diagnosis were recruited along with their caregivers. Caregivers could be an immediate or extended family member or a friend who provided care or assistance of any kind and took the responsibility for the stroke survivor and were recognised by the stroke survivor, not fully paid for caregiving. The on-site research nurses reviewed the list of stroke survivors on a daily basis to screen for eligible participants and conduct recruitment. All participants were explained the study purpose and procedures in their preferred language, and written informed consent was taken and documented. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point during the follow-up period, if they wished.

Data was collected at 3-monthly intervals, via in-person interviews at baseline, 3 month and 12 month time points, and via telephone interviews at 6 month and 9 month time points. Trained interviewers conducted interviews covering the health, social and financial domains. Several measures were taken to ensure good compliance and minimise attrition, such as sending reminders prior to scheduled interviews, scheduling interviews over weekends or evenings during weekdays, multiple contact attempts (up to three) before categorising as lost to follow-up. To ensure the standardisation and quality of data collection, main investigators trained the research assistants. The training sessions were video-recorded, and these recordings were used to train subsequent research assistants covering the content and method of data collection along with consent taking procedures. We enrolled multi-ethnic participants, and all participants were interviewed in their preferred language (eg, English, Mandarin, Malay or Tamil). Before collecting data, we pilot tested our survey on 40 participants from two of the five sites and finalised the survey forms after inclusion of necessary amendments. Further details about the S3 are reported elsewhere.7 23

Independent variables (caregiver)

With a primary focus on caregiver factors, following caregiver variables were considered for current analysis: socio-demographic characteristics, marital status, relationship with caregiver (caregiver being spouse, adult-child, sibling or others including distant relatives and friends), number of chronic ailments, co-residing status, caregiver burden, family conflict, social support, caregiver reported stroke survivor behavioural issues and adopted caregiver management approaches. Under the caregiver burden, we incorporated measures of both objective and subjective burden measured by the Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale24 and the Zarit Burden Interview,25 26 respectively. The family caregiving conflict scale recommended by Pearlin and colleagues was used to capture family conflict.27 Adapting Pearlin and colleagues’ description of social support, we incorporated both ‘instrumental’ and ‘expressive’ dimensions of social support, with former captured by presence of paid help or foreign domestic worker (FDW) for general household tasks or specifically for stroke survivor and latter captured by Pearlin’s 8-item perceived social support instrument.27 The caregiver reported occurrence of problematic behaviour by stroke survivors was recorded using the Revised Memory and Behavioural Problem Checklist, previously used in stroke survivors.28–31 Caregivers were asked whether any of the 21 problematic behaviours (eg, ‘asking the same question over and over’, ‘destroying property’, ‘crying and tearfulness’, etc) have occurred during the previous week. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale: 0=never, 1=not in the past week, 2=one to two times per week, 3=three to six times per week and 4=daily or more often.32 Separate summated scores were calculated across the three domains of disruptive, depressive and memory related behavioural problems with Cronbach’s alpha for each being 0.73, 0.87 and 0.90, respectively. To capture the care management approaches by stroke survivors’ caregivers, we used the revised Dementia Management Strategies Scale. Previously validated in Singapore,33 the scale has two subcomponents of positive and negative types of management strategies with good reported internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89 and 0.87, respectively).

Independent variables (stroke survivor)

Following baseline stroke survivor variables were considered: socio-demographic characteristics, marital status, ward class as a proxy of socioeconomic status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, type of stroke (ischaemic or non-ischaemic), recurrent or first stroke, stroke severity measured on National Institute of Health Scale (NIHSS), functional status measured on modified Rankin scale (mRS), impairment in cognition measured on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), discharge status and depression measured on the 11-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale. Ward class captured the category of the ward in which the stroke survivor stayed during the index hospitalisation. To make healthcare affordable for all, the Singaporean government subsidises inpatient stay in the tertiary care setting in a tiered manner. Based on financial assessment, the patients can be eligible to stay at A, B1, B2 or C ward types, being entitled to increasing level of subsidies. With quality of care remaining constant, the ward types usually differ in the amenities provided to the warded patients. For the current analysis, we categorised ward class into subsidised and non-subsidised categories.7 For scales with more than 10 missing cases (NIHSS, MMSE, Revised memory and behaviour checklist), we used the person mean substitution approach to impute for missing values for cases with less than half constituting items missing.34

Outcome variables

The outcome of interest was SCR participation, which comprised of participation at any of the following: rehabilitation at home, DRC or nursing homes. This information was captured in the survey at 3-monthly intervals by asking the caregiver, ‘Has the stroke survivor at any time during the last 3 months received rehabilitation? Please include any rehabilitation at home, DRC and nursing homes’. For the subsequent 3 to 12 months, we created a variable for capturing the SCR participation information collected at 6, 9 and 12 month interviews. It was coded as ‘yes’ if the caregiver reported any participation at either of the time points and ‘no’ if the caregiver reported no participation across all time points.

Data analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted to describe the caregiver and stroke survivor characteristics. We conducted bivariate analysis to examine the associations between independent variables (caregiver and stroke survivor factors) and the SCR participation. The independent variables with p values <0.1 on bivariate analysis were chosen as potential predictors for the multivariable regression model. With these potential predictor variables, we built the most parsimonious model using a backward variable selection approach. At each model building stage, the most insignificant variable was removed until we were left with the variables having a p value <0.05, except for age, gender, ethnicity and ward class of stroke survivors which were kept in the model. Logistic regression was used at both bivariate and model building stages and we reported the unadjusted and adjusted OR estimates with 95% CIs. We ran separate models for the SCR participation across the first 3 months post-stroke and subsequent 3 to 12 months as researchers have previously reported variations in the determinants of stroke survivors’ outcomes over these periods.7 35 The significance level was set at 5%. With the most parsimonious model, we performed diagnostics for the model fit using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test, checked for model misspecifications, multicollinearity and influential observations. All analysis was performed in Stata V.14.1.36

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

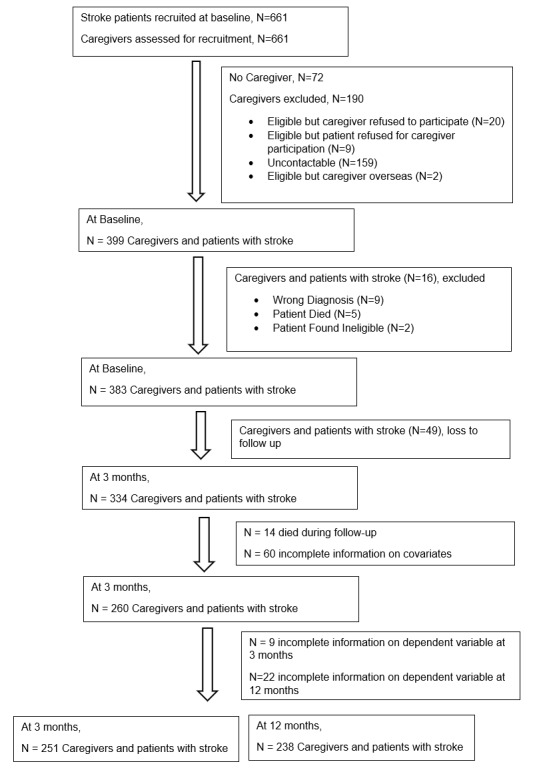

Out of the 661 caregivers assessed at baseline, 399 caregivers were recruited after exclusion of 190 caregivers and 72 stroke survivors not having a caregiver. Two hundred fifty-one stroke survivor-caregiver dyads were available for the current analysis after exclusion of stroke survivors with deaths within the follow-up period and limiting to complete cases (please refer figure 1 for study flowchart). The follow-up rates for caregivers were 87.2% and 73.4% at 3 and 12 months. The prevalence of SCR participation was 49% over 0 to 3 month periods and 25% over 3 to 12 month periods. The mean age of caregivers was 50.1 years, with the majority being female, married and co-residing with the stroke survivor. There were 61%, 28%, 4% and 7% of spousal, adult-child, sibling and other caregivers. The mean scores for memory-related, depressive and disruptive behaviour problems of stroke survivors were 5.01, 3.15 and 2.67, respectively and 34.27 (10.85) and 11.07 (4.60) were the mean (SD) scores for caregiver reported positive and negative care management strategies, respectively. The stroke survivors had a mean age of 61.8 years, with the majority being male (65%), of Chinese ethnicity (59%) and married (81%). About 89% had ischaemic index stroke and for 17%, the index stroke was a recurrent one. Out of all stroke survivors, 57%, 38% and 5% had a mild, moderately severe and severe type of index stroke as measured on NIHSS. More than half (59%) had moderate-to-severe disability3–5 on mRS (please refer tables 1 and 2). The findings from the diagnostics for model fit using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test are as follows: for 0 to 3 months model: p value=0.663; and for 3 to 12 months model: p value=0.778.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of participants (caregiver factors)

| All stroke survivors*, No. (%) |

Participated in SCR*, 3 months No. (%) |

Participated in SCR†, 3–12 months No. (%) |

||

| Variable | Category | |||

| CAREGIVER FACTORS | ||||

| Age of caregiver (in years) mean (SD) | 50.13 (13.09) | 49.03 (12.97) | 51.16 (10.76) | |

| Gender of caregiver | Male | 61 (23) | 29 (24) | 9 (16) |

| Female | 199 (77) | 93 (76) | 49 (84) | |

| Ethnicity of caregiver | Chinese | 151 (58) | 66 (54) | 35 (60) |

| Non-Chinese | 109 (42) | 56 (46) | 23 (40) | |

| Marital status of caregiver | Married | 205 (79) | 93 (76) | 47 (81) |

| Single | 55 (21) | 29 (24) | 11 (19) | |

| Caregiver identity | Spouse | 159 (61) | 71 (58) | 32 (55) |

| Adult-child | 74 (28) | 36 (30) | 17 (29) | |

| Sibling | 10 (4) | 6 (5) | 4 (7) | |

| Others | 17 (7) | 9 (7) | 5 (9) | |

| Co-residing with patient | Yes | 231 (89) | 109 (89) | 49 (84) |

| No | 29 (11) | 13 (11) | 9 (16) | |

| Caring for multiple care recipients | Yes | 108 (42) | 49 (40) | 22 (38) |

| No | 152 (58) | 73 (60) | 36 (62) | |

| Revised memory and behaviour checklist | ||||

| Memory problems | Mean (SD) | 5.01 (5.93) | 4.95 (6.30) | 5.09 (6.06) |

| Depressive behaviour problems | Mean (SD) | 3.15 (4.82) | 2.72 (4.21) | 3.61 (5.21) |

| Disruptive behaviour problems | Mean (SD) | 2.67 (3.62) | 1.97 (2.86) | 2.10 (2.83) |

| Caregiver Burden | ||||

| Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale | Mean (SD) | 31.71 (12.63) | 32.94 (12.02) | 35.18 (13.20) |

| Zarit Burden Interview | Mean (SD) | 8.73 (7.86) | 8.25 (6.83) | 8.74 (8.13) |

| Family conflict | ||||

| Attitude towards patient | Mean (SD) | 11.42 (4.49) | 11.58 (4.46) | 12.00 (4.12) |

| Attitude towards caregiver | Mean (SD) | 11.63 (4.37) | 11.68 (4.40) | 12.26 (3.91) |

| Social support (instrumental) | ||||

| FDW for general help | Yes | 212 (82) | 98 (80) | 42 (72) |

| No | 48 (18) | 24 (20) | 16 (28) | |

| FDW for stroke survivor | Yes | 33 (13) | 17 (14) | 11 (19) |

| No | 227 (87) | 105 (86) | 47 (81) | |

| Social support (perceived) | Mean (SD) | 26.33 (4.90) | 26.49 (5.03) | 25.95 (4.61) |

| Care management strategies | ||||

| Positive strategies | Mean (SD) | 34.27 (10.85) | 36.52 (10.19) | 35.88 (10.92) |

| Negative strategies | Mean (SD) | 11.07 (4.60) | 10.56 (4.34) | 11.36 (4.46) |

*N=251.

†N=238.

SCR, supervised community rehabilitation; No., number; FDW, foreign domestic worker.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of participants (stroke survivor factors)

| All stroke survivors*, No. (%) |

Participated in SCR*, 3 months No. (%) |

Participated in SCR†, 3–12 months No. (%) |

||

| Variable | Category | |||

| PATIENT FACTORS | ||||

| Age of patient (in years) |

Mean (SD) | 61.77 (10.42) | 60.86 (10.63) | 62.29 (10.53) |

| Gender of patient | Male | 169 (65) | 77 (63) | 37 (64) |

| Female | 91 (35) | 45 (37) | 21 (36) | |

| Ethnicity of patient | Chinese | 153 (59) | 65 (53) | 35 (60) |

| Non-Chinese | 107 (41) | 57 (47) | 23 (40) | |

| Marital status of patient | Married | 210 (81) | 97 (80) | 45 (78) |

| Single | 50 (19) | 25 (20) | 13 (22) | |

| Ward class | Unsubsidised | 21 (8) | 11 (9) | 7 (12) |

| Subsidised | 235 (92) | 110 (91) | 51 (88) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1–3 | 52 (20) | 22 (18) | 13 (22) |

| 4–6 | 165 (63) | 79 (65) | 31 (53) | |

| >=7 | 43 (17) | 21 (17) | 14 (24) | |

| Stroke type | Ischaemic | 231 (89) | 106 (87) | 48 (83) |

| Non-ischaemic | 29 (11) | 16 (13) | 10 (17) | |

| Recurrent stroke | Yes | 43 (17) | 16 (13) | 8 (14) |

| No | 217 (83) | 106 (87) | 50 (86) | |

| National Institute of Health Scale | Mild (0–4) | 149 (57) | 60 (49) | 23 (40) |

| Moderately severe (5-14) | 97 (38) | 55 (45) | 28 (48) | |

| Severe (15-24) | 14 (5) | 7 (6) | 7 (12) | |

| Modified Rankin Scale | No or slight disability (0–2) | 106 (41) | 38 (31) | 11 (19) |

| Moderate or severe disability (3-5) | 154 (59) | 84 (69) | 47 (81) | |

| Mini-Mental State Examination |

No cognitive impairment (24-30) | 150 (58) | 70 (57) | 30 (52) |

| Mild cognitive impairment (18-23) | 65 (25) | 33 (27) | 15 (26) | |

| Severe cognitive impairment (1-17) | 45 (17) | 19 (16) | 13 (22) | |

| Discharge to step-down facility (community hospital) | Yes | 66 (25) | 33 (27) | 19 (33) |

| No | 194 (75) | 89 (73) | 39 (67) | |

| Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | Mean (SD) | 6.31 (5.61) | 6.59 (5.51) | 6.60 (5.64) |

*N=251.

†N=238.

SCR, supervised community rehabilitation; No., number.

Supervised community rehabilitation participation (0 to 3 months post-stroke)

Online supplementary table 1 depicts the results of the association of caregiver and stroke survivor characteristics with odds of SCR participation across 3 months post-stroke. The bivariate associations of caregiver reported disruptive behaviour of stroke survivor and positive management strategy with SCR participation were statistically significant. Among the stroke survivor factors, the bivariate associations of stroke severity and functional status with SCR participation were statistically significant. The variables that entered the final adjusted model of odds of SCR participation over first 3 months post-stroke were caregiver reported disruptive behaviour of the stroke survivor, positive management strategy of the caregiver and stroke survivor’s functional status (please refer table 3). For every 1-unit increase in the caregiver reported stroke survivor’s disruptive behaviour score, the odds of SCR participation decreased by about 15% (OR: 0.845; 95% CI: 0.769 to 0.929). For every 1-unit increase in the caregiver reported positive care management strategy score, the odds of SCR participation increased by about 4% (OR: 1.039; 95% CI: 1.011 to 1.068). Compared with stroke survivors with no or mild functional disability, those with moderate-to-severe functional disability had 2.76 times the odds of SCR participation over the first 3 months post-stroke (p=0.001).

Table 3.

Multivariable regression analysis results of supervised community rehabilitation (any use) across 3 months post-stroke

| Variable | Reference category | Any rehabilitation (3 months) | |

| aOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Revised memory and behaviour checklist | |||

| Disruptive behaviour problems | 0.845 (0.769 to 0.929) | <0.001 | |

| Care management strategies | |||

| Positive strategies | 1.039 (1.011 to 1.068) | 0.006 | |

| Modified Rankin Scale | No or slight disability (0–2) | 0.001 | |

| Moderate or severe disability (3-5) | 2.759 (1.532 to 4.969) | ||

| Age (in years)* | 0.975 (0.949 to 1.002) | 0.074 | |

| Gender* | Male | 0.875 (0.480 to 1.594) | 0.662 |

| Ethnicity* | Non-Chinese | 0.723 (0.409 to 1.277) | 0.264 |

| Ward class* | Unsubsidised | 0.806 (0.298 to 2.180) | 0.671 |

*Model adjusted for patient’s age, gender, ethnicity and ward class.

aOR, adjusted OR.

bmjopen-2019-036631supp001.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)

Supervised community rehabilitation participation (3 to 12 months post-stroke)

Online supplementary table 2 depicts the results of the association of caregiver and stroke survivor characteristics with odds of SCR participation across 3 to 12 months post-stroke. The bivariate associations of caregiver burden (measured on Oberst Burden Scale), FDW for general help and FDW for stroke survivors with SCR participation were statistically significant. Among the stroke survivor factors, the bivariate associations of stroke severity and functional status with SCR participation were statistically significant. The only variable that entered the final adjusted model of odds of SCR participation 3 to 12 months post-stroke was the functional status, with odds of SCR participation being 4.23 times in those with moderate-to-severe functional disability when compared with those with none-to-mild disability (OR: 4.234; 95% CI: 2.034 to 8.812) (please refer table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analysis results of supervised community rehabilitation (any use) across 3 to 12 months post-stroke

| Variable | Reference category | Any rehabilitation (3–12 months) | |

| aOR* (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Modified Rankin Scale | No or slight disability (0–2) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate or severe disability (3-5) | 4.234 (2.034 to 8.812) | ||

| Age (in years)* | 0.999 (0.968 to 1.032) | 0.973 | |

| Gender* | 0.875 (0.448 to 1.709) | 0.695 | |

| Ethnicity* | 1.146 (0.603 to 2.176) | 0.678 | |

| Ward class* | 0.432 (0.146 to 1.279) | 0.130 | |

*Model adjusted for patient’s age, gender, ethnicity and ward class.

aOR, adjusted OR.

Discussion

We are among the first to establish that both the caregiver and stroke survivor factors jointly determine the participation in SCR post-stroke. We also demonstrated the variability in the determinants of SCR participation, with the caregiver determinants being significant over the early post-stroke period (0 to 3 months) and the stroke survivor determinants being significant over both the early and late post-stroke period (3 to 12 months).

Past literature has acquainted us fairly well with the role of caregiver factors, such as caregiver availability,17 support15 18 and psychosocial health14 in the functional recovery post-stroke. Clark and colleagues reported stronger chance beliefs of the caregivers to be associated with a decreased likelihood of their stroke survivors attending outpatient medicine and rehabilitation therapy appointments.37 Researchers have reported caregiver factors to be associated with delayed discharge from inpatient settings.38 39 Another study exploring the caregiver determinants of post-stroke inpatient rehabilitation reported co-residing caregivers to be associated with decreased utilisation of inpatient rehabilitation.40 We did not find any significant association between co-residing status and SCR participation. While authors in these studies demonstrated the role of caregivers in inpatient rehabilitation, our study adds new knowledge on the role of caregivers in SCR participation once they are discharged home.

We reported that caregiver factors played a significant role during the early post-stroke period, with the stroke survivors’ functional status being the only significant factor in the late post-stroke period. A possible explanation could be related to the transition to the community and related challenges in the early post-stroke period with caregivers playing a crucial role in the rehabilitation journey during this phase. Another possibility could be related to the improvement in functional status of stroke survivors over time, making them less reliant on caregivers during the late post-stroke period. The importance of this finding is further emphasised considering higher participation in supervised rehabilitation in the early post-stroke period is reported to be associated with better functional outcomes at 1 year post-stroke.41

We found that the odds of SCR participation increased with an increase in the positive care management strategy score. A possible explanation could be the caregivers adopting positive care management strategies adapt better to their new role with lower psychological issues like anxiety and are better able to care for the stroke survivors including the facilitation of SCR participation. Along the same lines, a cross-sectional study on patients suffering cerebrovascular accidents reported poorer functional outcomes in patients of caregivers having anxiety.14 We found that the odds of SCR participation decreased with an increase in the caregiver reported stroke survivor’s disruptive behaviour score. Managing problematic behaviours post-stroke can be difficult for the caregivers resulting in caregiver strain and termination of care provision42 and, in some circumstances, institutionalisation of stroke survivors.43 Similarly, in our setting, caregivers may be strained managing stroke survivor’s disruptive behaviour, limiting their ability to comply with their caregiving obligations, including facilitation of SCR participation.

Following are the practical implications of our work. Efforts should be directed towards promoting positive care management strategies among caregivers by optimising their efficacy in caregiving tasks so that they adapt well. Currently, caregiver competency training is mainly focussed on physical assistance. However, the scope should also include mastering skills to manage behavioural issues post-stroke. Management of such behavioural issues can be addressed under the three domains of memory-related, disruptive and depressive behavioural problems. Examples of the memory-related behavioural problems are asking the same questions over and over, trouble remembering events, difficulty concentrating on a task and so forth. Alternatively, stroke survivor may present with disruptive behavioural problems, such as talking loudly and rapidly, verbally aggressive to others, arguing and so forth. The stroke survivor may also exhibit depressive behavioural problems like being anxious or worried, crying or appearing sad. Considering the variability in the stroke survivors’ behavioural issues post-stroke, caregiver training should be supplemented with assessment of such behavioural problems post-stroke, which can enable the caregiving training to be tailored and specific towards caregivers’ management needs. Our results support the adoption of a family-centred approach to post-stroke rehabilitation providing due recognition to the family caregivers. A review on family-centred approach towards post-stroke rehabilitation recommended keeping the caregivers informed, involving them in setting rehabilitation goals, teaching coping skills and improving self-efficacy.44 Another practical recommendation would be to proactively conduct caregiver readiness assessment to ensure the stroke survivor-caregiver dyads adjust well in the community. One crucial point for conducting readiness assessment is before discharge to home from inpatient rehabilitation setting.6 Building on work done by researchers describing stroke survivors’ needs related to re-integration into community post-discharge,45 and caregivers’ needs related to caregiving and facilitating community transition,46 readiness assessment at discharge should focus on stroke survivors’ functional needs, community re-integration challenges, caregivers’ commitment and capacity to care (ie, assessing for pre-existing health issues and self-care strategies), prior caregiving experience, available resources and overall impact of stroke.46

Study limitations

Following are the limitations. There is a possibility of information bias related to the limited recall of SCR participation. To address this, we kept our recall period to 3 months as past literature recommends shorter recall periods to ensure greater accuracy of reporting utilisation.47 We limited the current sample to patients with stroke surviving the first post-stroke year, excluding deaths within the follow-up period (<5%). Considering the possibility of systematic differences in survivors and those who died during the follow-up, our findings would be generalisable to stroke survivors alive at the end of first year post-stroke. With respect to caregiver related exclusions, we limited the current sample to stroke survivors with available caregivers at baseline, excluding those without any caregivers (11%). Considering the scope of the current study, which was examining the determinants of SCR participation adopting a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach, along with the exclusion of stroke survivors without a caregiver, the generalisability of our findings is limited to those stroke survivors who have a caregiver post-stroke. To further comment on the representativeness of our sample, we compared the demographic characteristics of current sample with the estimates from the Singapore Stroke Registry for the year of 2013. With a mean age of 61.77 years, our cohort was on average younger than the national cohort by about 6 years. Both the cohorts were similar with respect to having higher proportion of male stroke survivors and those of Chinese ethnicity. Refusal to participate by both the stroke survivors and their caregivers could be one of the factors that can potentially introduce selection bias. This is especially relevant if those who refused to participate are systematically different from those who didn’t, in factors of direct relevance to this study. We were not able to capture reasons for refusal to participate. However, the proportion of caregivers excluded due to refusal to participate either by the caregivers (3%) or their stroke survivors (1.4%) was low, so the possibility of refusals biassing our findings is unlikely. Also, as with any longitudinal study, we encountered a relatively lower response rate over the late post-stroke period. Another limitation is related to the temporality across caregiver characteristics and SCR participation over the first 3 months post-stroke as both were determined simultaneously. However, we did have the temporality across caregiver characteristics and SCR participation over 3 to 12 months post-stroke. We did not include environment as one of the factors in the current analysis as our scope was limited to stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic level, excluding macro-level variables. While it is recommended to consider environment or person-environment interaction in the context of participation post-stroke,48 49 the inclusion of environment as an independent variable is complicated by the inherent challenges in the conceptualisation, measurement and analysis of this construct, which is reported to be generic and broad.49 50 Moreover, environment as a factor is reported to be significant in studying the activities of daily living participation level51 as compared with healthcare service utilisation. Future studies can build on the current findings to explore the influence of environment on the association of stroke survivor-caregiver factors and the SCR participation.

Study strengths

Our study has some strengths. We are among the first, to the best of our knowledge, to demonstrate the role caregivers play in stroke survivor’s SCR participation. Our results have substantiated to some extent the rationale for the adoption of a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach7 to studying post-stroke SCR utilisation. We reported the relative importance of caregiver factors in early as compared with late post-stroke period. Another strength was the comprehensiveness of caregiver variables considered which enabled us to explore the role of caregivers in depth. Being a multicentre study enhances the representativeness of the recruited sample. In addition, we did not have any language barriers to recruitment, enrolling multi-ethnic participants into the study, which further increases the generalisability of our findings.

Conclusion

With the aim to study the caregiver determinants of SCR participation after stroke, our study demonstrated that the SCR participation is determined by both the caregiver and the stroke survivor characteristics. We found that the caregiver’s positive care management strategies increased the odds of SCR participation and the caregiver reported stroke survivor’s disruptive behaviour decreased the odds of SCR participation over 3 months post-stroke. Our results support the adoption of a stroke survivor-caregiver dyadic approach for studying post-stroke utilisation of community rehabilitation services. Within practice settings, dyadic approach should include promotion of positive care management strategies, comprehensive caregiving training including both physical and behavioural dimensions, active engagement of caregivers in rehabilitation and conducting regular caregiver needs assessments in the community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the medical staff at the public tertiary hospitals for assisting with the recruitment of patients and their caregivers. We would also like to thank all the participants in our study for their participation and cooperation.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST was involved in conceptualisation and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, original draft preparation and incorporating revisions in manuscript based on critical inputs from other co-authors. GCHK was involved in conceptualisation and design of the study, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript and providing critical inputs to revision of manuscript along with supervision of the study. NL was involved in conceptualisation and design of the study, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript and providing critical inputs to revision of manuscript. KBT was involved in conceptualisation and design of the study, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript and providing critical inputs to revision of manuscript. HH made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study specifically with provision of expertise in medical domain and was involved in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. DBM made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study specifically, with provision of expertise in medical domain and was involved in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. JY made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study specifically with provision of expertise in financial domain and was involved in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. AC made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study specifically with provision of expertise in social domain and was involved in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. KEL was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. NV was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. EM was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. KMC was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. DADS was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. PY was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. BYT was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. EC was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. SHY was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. YSN was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. TMT was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. YHA was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. KHK was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. RS was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. RAM was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. HMC was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. TTY was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. CN was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. AC was involved in acquisition of data and in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. CST was involved in conceptualisation and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and providing critical inputs to revision of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and are agreeable to take accountability of all aspects of the work involved in the manuscript.

Funding: This research is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under the Centre Grant Programme - Singapore Population Health Improvement Centre (NMRC/CG/C026/2017_NUHS) and by the MOH Health Services Research Competitive Research Grant (Project Number: HSRG/0006/2010) from the National Medical Research Council, Singapore.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Singapore Stroke Study was approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board, SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board and the National Health Group Domain Specific Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from both the patients and the caregivers in their preferred language by trained researchers.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. The data set used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. Preventing stroke: saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:182–7. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70031-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Registry SS. Trends in stroke in Singapore 2005-2012. Singapore: National Registry of Diseases Office, Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JI, Tsoi C, Marsella A. Optimizing stroke systems of care by enhancing transitions across care environments. Stroke 2008;39:2637–43. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutz BJ, Young ME, Cox KJ, et al. The crisis of stroke: experiences of patients and their family caregivers. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18:786–97. 10.1310/tsr1806-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2006;113:e85–151. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutz BJ, Young ME, Creasy KR, et al. Improving stroke caregiver readiness for transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home. Gerontologist 2016;38:gnw135–9. 10.1093/geront/gnw135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tyagi S, Koh GCH, Luo N, et al. Dyadic approach to post-stroke hospitalizations: role of caregiver and patient characteristics. BMC Neurol 2019;19:267. 10.1186/s12883-019-1510-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association and American stroke association. Stroke 2014;45:2836–52. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy MJ, Lyons KS, Powers LE. Expanding poststroke depression research: movement toward a dyadic perspective. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18:450–60. 10.1310/tsr1805-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyagi S, Tan CS, Choon-Huat Koh G. Dyadic approach to outpatient healthcare utilization by stroke patients: can caregivers make a difference? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018;99:e45 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons KS, Lee CS. The theory of Dyadic illness management. J Fam Nurs 2018;24:8–28. 10.1177/1074840717745669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyons KS, Vellone E, Lee CS, et al. A dyadic approach to managing heart failure with confidence. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015;30:S64–71. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon H, Adams KB. The effectiveness of dyadic interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia 2013;12:821–39. 10.1177/1471301212447026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Em S, Bozkurt M, Caglayan M, et al. Psychological health of caregivers and association with functional status of stroke patients. Top Stroke Rehabil 2017;24:323–9. 10.1080/10749357.2017.1280901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris JE, Eng JJ, Miller WC, et al. The role of caregiver involvement in upper-limb treatment in individuals with subacute stroke. Phys Ther 2010;90:1302–10. 10.2522/ptj.20090349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh GC-H, Chen C, Cheong A, et al. Trade-Offs between effectiveness and efficiency in stroke rehabilitation. Int J Stroke 2012;7:606–14. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GCH K, Wee LE, Chen C, et al. Caregivers and their impact on inpatient rehabilitation efficiency and effectiveness amongst recent stroke survivors in an urbanised Asian Society. Am Heart Assoc 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsouna-Hadjis E, Vemmos KN, Zakopoulos N, et al. First-stroke recovery process: the role of family social support. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:881–7. 10.1053/apmr.2000.4435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker AC. The spouse's positive effect on the stroke patient's recovery. Rehabil Nurs 1993;18:30–3. 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1993.tb01283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang Y, Tao Q, Zhou X, et al. Patient and family member factors influencing outcomes of poststroke inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:249–55. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Koh GC-H, Naidoo N, et al. Trends in length of stay, functional outcomes, and discharge destination stratified by disease type for inpatient rehabilitation in Singapore community hospitals from 1996 to 2005. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1342–51. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health (MOH), Singapore Intermediate and long-term care (ILTC) services. Available: https://http://www.moh.gov.sg/our-healthcare-system/healthcare-services-and-facilities/intermediate-and-long-term-care-(iltc)-services [Accessed 5 Nov 2018].

- 23.Tyagi S, Koh GC-H, Nan L, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost trajectories post-stroke: role of caregiver and stroke factors. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:881. 10.1186/s12913-018-3696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakas T, Austin JK, Jessup SL, et al. Time and difficulty of tasks provided by family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs 2004;36:95–106. 10.1097/01376517-200404000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652–7. 10.1093/geront/41.5.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seng BK, Luo N, Ng WY, et al. Validity and reliability of the Zarit burden interview in assessing caregiving burden. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2010;39:758–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990;30:583–94. 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakas T, Kroenke K, Plue LD, et al. Outcomes among family caregivers of aphasic versus nonaphasic stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs 2006;31:33–42. 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2006.tb00008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark PC, Dunbar SB, Aycock DM, et al. Caregiver perspectives of memory and behavior changes in stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs 2006;31:26–32. 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2006.tb00007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez C, Bakas T. Factors associated with stroke survivor behaviors as identified by family caregivers. Rehabil Nurs 2013;38:202–11. 10.1002/rnj.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haley WE, Allen JY, Grant JS, et al. Problems and benefits reported by stroke family caregivers: results from a prospective epidemiological study. Stroke 2009;40:2129–33. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.545269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, et al. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging 1992;7:622–31. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.4.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan L, Yap P, Ng WY, et al. Exploring the use of the dementia management strategies scale in caregivers of persons with dementia in Singapore. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:935–41. 10.1080/13607863.2013.768209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downey RG, King C. Missing data in Likert ratings: a comparison of replacement methods. J Gen Psychol 1998;125:175–91. 10.1080/00221309809595542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjerkreim AT, Thomassen L, Brøgger J, et al. Causes and predictors for hospital readmission after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:2095–101. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark AN, Sander AM, Pappadis MR, et al. Caregiver characteristics and their relationship to health service utilization in minority patients with first episode stroke. NeuroRehabilitation 2010;27:95–104. 10.3233/NRE-2010-0584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai W, Buttineau M, Harvey JK, et al. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of exceeding target length of stay during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil 2017;24:510–6. 10.1080/10749357.2017.1325589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan WS, Chong WF, Chua KSG, et al. Factors associated with delayed discharges after inpatient stroke rehabilitation in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2010;39:435–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinojosa MS, Rittman M, Hinojosa R. Informal caregivers and racial/ethnic variation in health service use of stroke survivors. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46:233–41. 10.1682/JRRD.2007.10.0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koh GC-H, Saxena SK, Ng T-P, et al. Effect of duration, participation rate, and supervision during community rehabilitation on functional outcomes in the first poststroke year in Singapore. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:279–86. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cameron JI, Cheung AM, Streiner DL, et al. Stroke survivors' behavioral and psychologic symptoms are associated with informal caregivers' experiences of depression. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:177–83. 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephens S. Who's there?: when stroke or Alzheimer's changes a person's behavior, caregiving can become extreme. here, experienced caregivers, patients, and experts share their stories and advice. Neurology Now 2009;5:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visser-Meily A, Post M, Gorter JW, et al. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:1557–61. 10.1080/09638280600648215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glickman LB, Chimatiro G. Clients with stroke and non-stroke and their guardians' views on community reintegration status after in-patient rehabilitation. Malawi Med J 2018;30:174–9. 10.4314/mmj.v30i3.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young ME, Lutz BJ, Creasy KR, et al. A comprehensive assessment of family caregivers of stroke survivors during inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1892–902. 10.3109/09638288.2014.881565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-Reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:217–35. 10.1177/1077558705285298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organisation International classification of functioning, disability and Health: Children & Youth Version. ICF-CY: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP. Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concerning participation and environmental factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:S22–35. 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keysor J, Jette A, Haley S. Development of the home and community environment (HACE) instrument. J Rehabil Med 2005;37:37–44. 10.1080/16501970410014830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keysor JJ, Jette AM, Coster W, et al. Association of environmental factors with levels of home and community participation in an adult rehabilitation cohort. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1566–75. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036631supp001.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)